Abstract

GABAergic inhibition in the central nervous system (CNS) can occur via rapid, transient postsynaptic currents and via a tonic increase in membrane conductance, mediated by synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors (GABAARs) respectively. Retinal bipolar cells (BCs) exhibit a tonic current mediated by GABACRs in their axon terminal, in addition to synaptic GABAAR and GABACR currents, which strongly regulate BC output. The tonic GABACR current in BC terminals (BCTs) is not dependent on vesicular GABA release, but properties such as the alternative source of GABA and the identity of the GABACRs remain unknown. Following a recent report that tonic GABA release from cerebellar glial cells is mediated by Bestrophin 1 anion channels, we have investigated their role in non-vesicular GABA release in the retina. Using patch-clamp recordings from BCTs in goldfish retinal slices, we find that the tonic GABACR current is not reduced by the anion channel inhibitors NPPB or flufenamic acid but is reduced by DIDS, which decreases the tonic current without directly affecting GABACRs. All three drugs also exhibit non-specific effects including inhibition of GABA transporters. GABACR ρ subunits can form homomeric and heteromeric receptors that differ in their properties, but BC GABACRs are thought to be ρ1-ρ2 heteromers. To investigate whether GABACRs mediating tonic and synaptic currents may differ in their subunit composition, as is the case for GABAARs, we have examined the effects of two antagonists that show partial ρ subunit selectivity: picrotoxin and cyclothiazide. Tonic and synaptic GABACR currents were differentially affected by both drugs, suggesting that a population of homomeric ρ1 receptors contributes to the tonic current. These results extend our understanding of the multiple forms of GABAergic inhibition that exist in the CNS and contribute to visual signal processing in the retina.

Introduction

GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, evokes transient postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) via ionotropic GABAA and GABAC receptors, as well as slower synaptic responses via metabotropic GABAB receptors (GABARs). In addition, there is increasing evidence that GABA evokes a tonic increase in membrane conductance by activating extrasynaptic GABA receptors, either as a result of spill-over from synapses or via a non-synaptic mechanism [1]. Tonic GABAR currents are mediated by GABAARs in brain regions such as the hippocampus, cerebellum and thalamus, where they have a role in controlling neuronal excitability and network interactions [2], [3]. In the retina, a GABACR-mediated tonic current occurs in the synaptic terminals of bipolar cells (BCs), which similarly regulates membrane excitability [4], [5]. Bipolar cell terminals (BCTs) also exhibit rapid synaptic GABAAR and GABACR currents that mediate feedback inhibition and limit BC glutamate release, thereby modulating the light responses of ganglion cells, the output cells of the retina [6].

We have found that the tonic GABACR current in BCTs, like some tonic GABAAR currents [7]–[10], is not dependent on vesicular GABA release [11]. The alternative source of GABA is currently unknown but does not appear to involve reversal of GABA transporters or release via hemichannels or P2X7 receptors [11]. It was recently shown that the tonic release of GABA from cerebellar glial cells can occur via Bestrophin 1 (Best1) Cl- channels [12], which have a significant permeability to large anions such as thiocyanate, gluconate and glutamate [13], [14]. In addition, volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs) have been implicated in the non-vesicular release of neurotransmitters [15]. Astrocytic or neuronal release via anion channels may therefore be a potential source of GABA for activating the tonic GABACR current in BCTs.

Tonic GABAAR currents are mediated by receptors that differ in their subunit composition from synaptic GABAARs, conferring distinct receptor properties that are suited to their localization and function, such as high GABA sensitivity and reduced desensitization [16], [17]. GABACRs are composed of ρ subunits which are highly expressed in the retina but are also localized to various brain regions including the midbrain, thalamus, hippocampus and cerebellum [18]. BC GABACRs are believed to be ρ1-ρ2 heteromers, although ρ subunits can also co-assemble with GABAAR γ subunits [19], [20]. Heterologous expression of ρ1 and/or ρ2 subunits reveals differences in receptor properties, for example ρ1 homomers exhibit higher GABA sensitivity, lower conductance and slower deactivation than ρ2 homomers, with heteromeric ρ1-ρ2 receptors generally showing intermediate properties [21]–[24]. However, it is unknown whether receptor subunit diversity contributes to the different forms of GABACR-mediated inhibition in BCTs.

To further investigate the activation and receptor properties of GABACRs mediating the tonic current in BCTs, we have examined the effect of anion channel inhibitors and subunit-selective antagonists on spontaneous and evoked GABACR currents recorded directly from BCTs in goldfish retinal slices. We find evidence for a role of DIDS-sensitive anion channels/exchangers in tonic GABA release, and for a contribution of homomeric ρ1 receptors to the tonic GABACR current.

Methods

Goldfish (Carassius auratus) were maintained in a 12 hour dark/light cycle at 16°C. Prior to use, light-adapted goldfish were dark-adapted for 1 hour to facilitate removal of the pigment epithelium. Goldfish were killed by decapitation followed immediately by destruction of the brain and spinal cord under Schedule 1 of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The experiments were approved by Keele University's Central Animal Facility Management Committee. The eyeballs were removed and retinae dissected out and treated for 25 minutes with hyaluronidase to remove vitreous humor. Each retina was quartered, placed ganglion cell layer down on filter paper and kept until needed at 4°C in medium comprising (mM): NaCl (127), KCl (2.5), MgCl2 (1.0), CaCl2 (0.5), Hepes (5), glucose (12), adjusted to pH 7.45 with NaOH. Slices were cut at 250 µm intervals, transferred to the recording chamber and perfused (1 ml.min-1) with medium comprising (mM): NaCl (108), KCl (2.5), MgCl2 (1.0), CaCl2 (2.5), NaHCO3 (24), glucose (12), gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. For Ca2+-free extracellular solution, CaCl2 was omitted and MgCl2 was increased to 3.5 mM, to maintain the divalent cation concentration. The osmolarities of the 2.5 mM Ca2+ and Ca2+-free extracellular solutions were 267 mOsm and 269 mOsm respectively. Slice preparation and recordings were performed at room temperature (18–22°C), in daylight conditions.

Drugs were bath-applied via the extracellular solution and locally-applied via pressure application from a low resistance glass micropipette (∼5 µm tip diameter) positioned 25-50 µm from the recorded BCT using a Picospritzer II (Intracell, Royston, UK). GABA and L-glutamate solutions for local application also contained bicuculline (50 µM). L-glutamate-evoked GABA responses were evoked at intervals of at least 30 s in order to avoid short-term depression of GABA release [25]. Salts and drugs, including GABA, L-glutamate, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB), 2-(3-trifluoromethylphenylamino)-benzoic acid (flufenamic acid), 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (DIDS), picrotoxin, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid (TPMPA), bicuculline, 1,2,5,6-tetrahydro-1-2-(diphenylmethylene)aminooxyethyl-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid hydrochloride (NO-711) and cyclothiazide were obtained from Tocris (Bristol, UK), Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK) and Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK).

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained from large Mb-type BC terminals, as described previously [26]. Most recordings were made from axon-severed terminals (determined by their capacitive current) [26] to eliminate currents arising from somatodendritic receptors and reduce the leak current. However, no differences in GABAR currents were observed between axon-severed terminals and the terminals of intact BCs. Patch pipettes (5–8 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass and filled with solution comprising (mM): CsCl (115), Hepes (25), TEA-Cl (10), Mg-ATP (3), Na-GTP (0.5), EGTA (0.5), pH 7.2, 270 mOsm. CsCl-based intracellular solution was used to increase the driving force through GABARs at a holding potential of −60 mV.

Membrane current (IM) was recorded via an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier controlled by Patchmaster software (HEKA, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany). Series resistance (RS) was monitored and recordings were not used if IM changes were accompanied by changes in RS. Off-line analysis was performed using IgorPro software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Pooled data are expressed as mean ± SEM; statistical significance was assessed using paired or unpaired Student's t tests as appropriate, with P<0.05 considered significant.

Results

The role of anion channels: Effects of NPPB and flufenamic acid

In order to investigate the role of Best1 and other anion channels in non-vesicular GABA release in the retina, we tested the effect of anion channel inhibitors on GABACR-mediated currents in BCTs. Recordings were made with CsCl-based intracellular solution at a holding potential of −60 mV, in the presence of bicuculline (50 µM) to block GABAAR-mediated spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs). The anion channel inhibitors were tested under both normal (2.5 mM) Ca2+ and Ca2+-free extracellular conditions; when no differences were observed between these conditions, the data has been pooled.

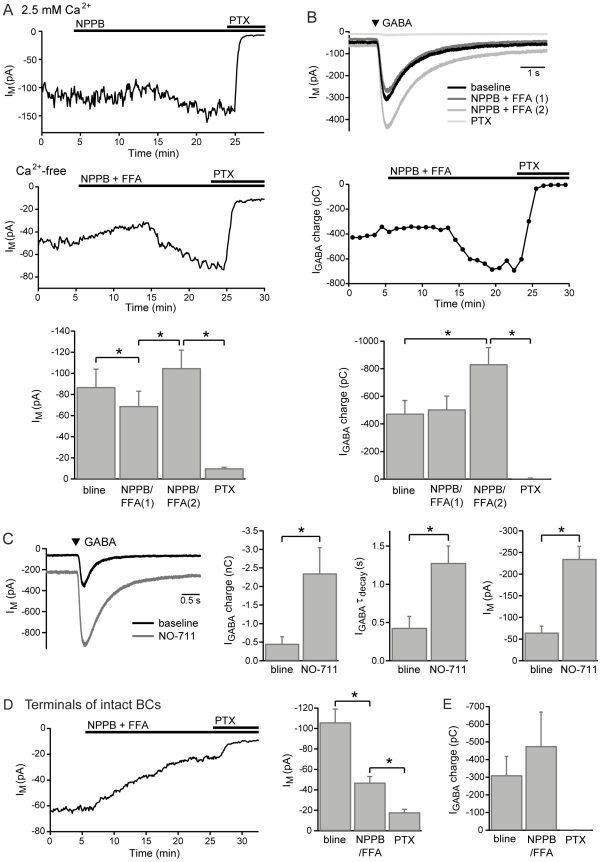

Application of the anion channel inhibitor NPPB (50-100 µM) to axon-severed BCTs initially evoked a small decrease, followed by an increase, in the holding current over the course of about 20 minutes (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 2, Ca2+-free n = 2; fig. 1A). Application of flufenamic acid (FFA; 100–200 µM), either alone (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 2) or in combination with NPPB (Ca2+-free n = 2), evoked the same biphasic effect (fig. 1A). The potentiated current in NPPB and/or FFA was subsequently inhibited by the addition of the GABAR antagonist picrotoxin (200 µM; 2.5 mM Ca2+ NPPB n = 1, FFA n = 1; Ca2+-free NPPB n = 1, NPPB+FFA n = 2; fig. 1A), confirming that it was mediated by GABACRs. Responses to locally-applied GABA (100 µM, 50–100 ms application) were monitored in the same experiments to check for direct inhibition of GABACRs by the anion channel blockers. The charge of GABA-evoked responses was not reduced by NPPB (n = 3), FFA (n = 1) or combined application (n = 2). Instead, a significant potentiation of GABA-evoked responses was observed, which occurred in parallel with the tonic current increase (fig. 1B). The GABA-evoked responses were subsequently fully blocked by picrotoxin (n = 4; fig. 1B).

Figure 1. The effect of NPPB and FFA on GABACR currents.

A, Example experiments and mean data (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 4, Ca2+-free n = 4) showing the effects of NPPB (50–100 µM) and FFA (100–200 µM) on the holding current in recordings from axon-severed BCTs, with subsequent addition of picrotoxin (PTX; 200 µM). NPPB/FFA(1) was measured 5–10 mins after drug application; NPPB/FFA(2) was measured 10–20 mins after application. B, Example GABACR responses evoked by local application of GABA (100 µM, 100 ms) and the charge of GABA-evoked responses against time for the recording in Ca2+-free conditions in A, with mean data (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 2, Ca2+-free n = 4) showing the effect of NPPB and/or FFA on the charge of GABA-evoked responses. C, Example responses and mean data (n = 6) showing the effect of the GAT-1 inhibitor NO-711 (3 µM) on GABA-evoked responses (100 µM, 50–100 ms), and the associated increase in the tonic GABACR current. D, An example experiment in Ca2+-free extracellular solution and mean data (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 3, Ca2+-free n = 4) showing the effect of NPPB (50 µM) and/or FFA (100–200 µM) on the holding current in recordings from the terminals of intact BCs, with subsequent addition of picrotoxin (200 µM). E, Mean data showing the effect of NPPB (50 µM) and/or FFA (100-200 µM) on the charge of GABA-evoked responses (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 2, Ca2+-free n = 3) in recordings from the terminals of intact BCs. All experiments in this and subsequent figures were performed with CsCl-based intracellular solution at a holding potential of -60 mV in the presence of bicuculline (50 µM), unless stated otherwise. Example evoked currents show the average of 2–5 responses in each condition. Error bars represent SEM; * denotes P<0.05.

The potentiating effects of NPPB and FFA on both the tonic current and exogenous GABA responses may result from inhibition of GABA uptake, as inhibition of GAT-1 by NO-711 (3 µM) exerts a similar, though more pronounced, potentiating effect on the tonic current [4] and on the charge of GABA-evoked responses (n = 6; fig. 1C). FFA and the related compound niflumic acid have previously been found to inhibit certain GAT isoforms to variable extents [27]. The small initial decrease in the holding current may indicate a minor contribution of NPPB/FFA-sensitive anion channels to non-vesicular GABA release, or may result from a non-specific effect of these drugs on other ion channels (see below).

A markedly different effect of NPPB and FFA was observed in recordings made from the terminals of intact BCs. Application of NPPB (50 µM; n = 3), FFA (100–200 µM; n = 2) or both in combination (n = 2) resulted in a significant reduction in the holding current (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 3, Ca2+-free n = 4), which was subsequently further reduced by application of picrotoxin (200 µM; fig. 1D). Conversely, responses evoked by local application of GABA (100 µM, 50–100 ms) were potentiated by NPPB and/or FFA in 4 out of 5 of these recordings (fig. 1E). The inhibitory effect of NPPB and FFA on the holding current of intact BC recordings is most likely due to the additional action of these drugs as hemichannel inhibitors [28]-[31], as Mb-type BCs in goldfish retina are connected via gap junctions in their dendrites [32]. The hemichannels appear to account for a major part of the increased membrane conductance of intact BCs compared with axon-severed BCTs [26].

The role of anion channels: Effects of DIDS

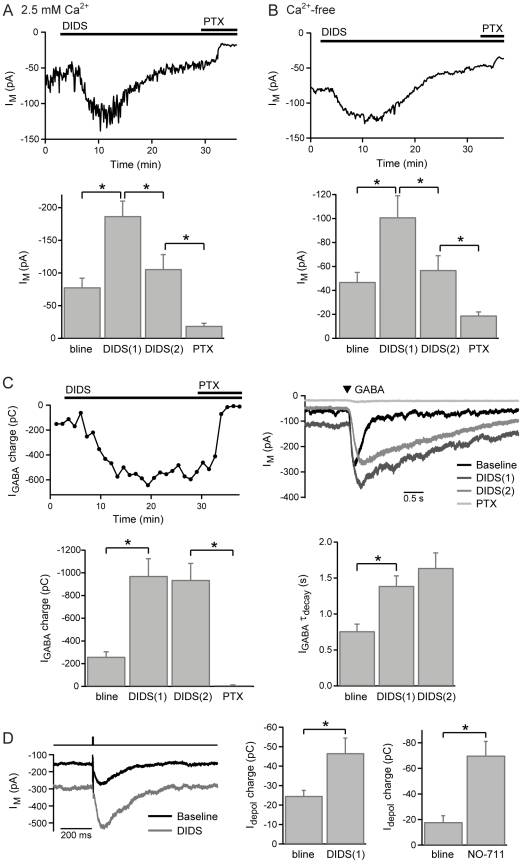

The anion channel/exchanger inhibitor DIDS, which has no reported effect on hemichannels [28], reduces the tonic release of glutamate in hippocampal slices [33]. The effect of DIDS on the GABACR tonic current in BCTs was therefore investigated. Application of DIDS (500 µM) to axon-severed BCTs in the presence of bicuculline (50 µM) initially caused a significant increase in the holding current (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 9; Ca2+-free n = 11; fig. 2A,B), that was accompanied by a large increase in the amplitude and slowing of the decay of responses evoked by exogenous GABA (100 µM, 50–100 ms; n = 14; fig. 2C). In addition, DIDS potentiated GABACR-mediated feedback currents evoked by activation of amacrine cell reciprocal synapses by brief BCT depolarization (to −10 mV for 5 ms; n = 5; fig. 2D). A similar, though larger, potentiation of synaptic feedback currents is evoked by the GAT-1 inhibitor NO-711 (3 µM; n = 6; fig. 2D) [4]. These effects are consistent with the reported action of DIDS as an inhibitor of GAT-1 [34].

Figure 2. The effect of DIDS on GABACR currents.

A, Example experiment and mean data (n = 9) showing the biphasic effect of DIDS (500 µM) on the holding current in normal Ca2+ extracellular solution, with subsequent application of picrotoxin (200 µM). DIDS(1) was measured at the peak of the tonic current potentiation, DIDS(2) was measured following 15-30 mins of DIDS application, just prior to addition of picrotoxin. B, Example experiment and mean data (n = 11) showing a similar effect of DIDS (500 µM) in Ca2+-free extracellular solution. C, The charge of GABA-evoked responses (100 µM, 100 ms) against time and example responses for the experiment in A, with mean data (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 7, Ca2+-free n = 7) showing the effect of DIDS on the charge and the decay time-constant of GABA-evoked responses. D, Example responses and mean data showing the effects of DIDS (500 µM; n = 5) and NO-711 (3 µM; n = 6) on the charge of GABACR-mediated synaptic feedback responses evoked by brief BCT depolarization (to -10 mV for 5 ms).

However, in the continuing presence of DIDS, the tonic current gradually decreased. In 2.5 mM extracellular Ca2+, the holding current decreased from a peak of -187±23 pA to -106±22 pA following 15–30 minutes of DIDS application (n = 9), and was further reduced to −19±4 pA by subsequently addition of picrotoxin (200 µM; n = 7; fig. 2A). In Ca2+-free extracellular solution, the holding current decreased from a peak of −101±18 pA to -57±12 pA following 15–30 minutes of DIDS application (n = 11), and was further reduced to -19±3 pA by subsequently addition of picrotoxin (200 µM; n = 8; fig. 2B). During the period of tonic current reduction there was no significant change in the charge or rate of decay of responses evoked by exogenous GABA (2.5 mM Ca2+ n = 7, Ca2+-free n = 7; fig. 2C), which were subsequently eliminated by picrotoxin (200 µM; fig. 2C). These results strongly suggest that DIDS reduces the tonic current without directly affecting BCT GABACRs, and is therefore likely to be an inhibitor of the non-vesicular GABA release mechanism.

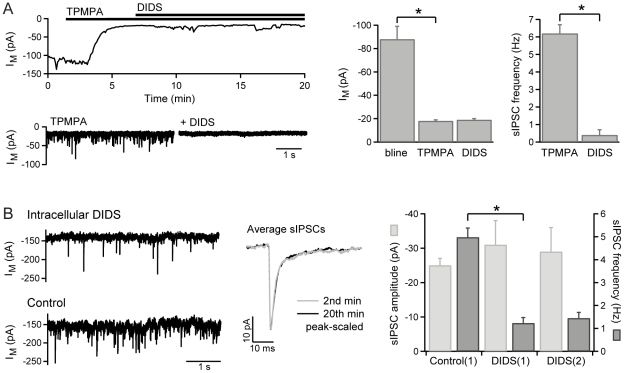

To confirm that the effects of DIDS are mediated by changes in the activation of GABACRs, and to investigate reported effects of DIDS as an inhibitor of GABAARs [35], DIDS (500 µM) was applied following inhibition of GABACRs with TPMPA (100–200 µM), in 2.5 mM Ca2+ extracellular solution without bicuculline. Under these conditions, GABAAR-mediated sIPSCs are observed [5]. In the presence of TPMPA, DIDS had no effect on the holding current, but did significantly reduce the frequency of sIPSCs (fig. 3A). DIDS has previously been used in combination with CsF as an intracellular inhibitor of GABAARs [36]–[38], based on evidence that it blocks other types of Cl- channel from either side of the membrane [39], [40]. To ascertain whether DIDS acts as an intracellular blocker of GABAARs in BCTs, recordings were made with DIDS (0.5–1 mM) included in the intracellular solution. Intracellular DIDS had no effect on the amplitude of sIPSCs but significantly reduced their frequency, compared with control recordings (n = 5 for DIDS and control, sIPSCs measured during the 2nd minute after gaining whole-cell access; fig. 3B). Intracellular DIDS appeared to reduce the longevity of whole-cell recordings (average duration 10±3 minutes, n = 5), but the amplitude and frequency of sIPSCs did not change during the course of recordings (2nd minute compared with 6th minute, n = 5; fig. 3B), and sIPSCs were still observed in the 20th minute of the longest duration recording (fig. 3B). DIDS therefore appears to act as an intracellular inhibitor of GABAARs, but is more effective when applied extracellularly.

Figure 3. The effect of DIDS on GABAAR currents.

A, An example recording and mean data (n = 4) showing that application of DIDS (500 µM) in the presence of TPMPA (200 µM) but not bicuculline has no effect on the holding current but inhibits spontaneous GABAAR-mediated IPSCs (sIPSCs). B, Example current traces from recordings with and without DIDS (500 µM) included in the intracellular solution, with average sIPSCs from a different recording with intracellular DIDS (500 µM), and mean sIPSC amplitude and frequency data in control recordings (n = 5) and recordings with intracellular DIDS (0.5–1 mM; n = 5). Control(1) and DIDS(1) were measured during the 2nd minute after gaining whole-cell access, DIDS(2) was measured during the 6th minute.

GABACR subunit composition: Picrotoxin-sensitivity

To investigate whether the ρ subunit composition of GABACRs mediating the tonic current differs from that of GABACRs mediating the relatively fast synaptic currents in BCTs, we have examined the effect of receptor antagonists that display some subunit-selectivity. As above, GABACR currents were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV with CsCl-based intracellular solution in the presence of the GABAAR antagonist bicuculline (50 µM).

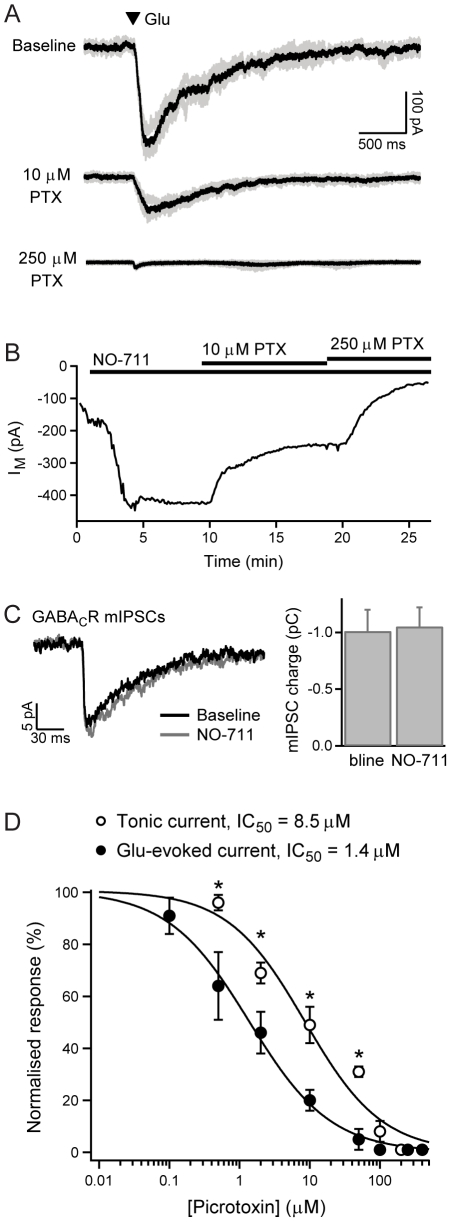

The inhibition of GABACRs by picrotoxin is dependent on subunit composition, with homomeric ρ1 receptors exhibiting approximately 10-fold higher IC50 values than either ρ2 homomers or ρ1- ρ2 heteromers in the presence of high GABA concentrations [21]–[23], [41]. The picrotoxin-sensitivity of tonic and synaptic GABACR currents in BCTs was therefore examined. Reciprocal amacrine cell synapses were activated by local application of L-glutamate (glu; 100 µM, 10 ms), which evokes large GABACR-mediated currents in BCTs [11]. The glu-evoked responses were maximally-inhibited by 250 µM picrotoxin; application of 400 µM picrotoxin had no further effect (n = 3). After obtaining baseline glu-evoked responses, picrotoxin was applied at a concentration of 0.1, 0.5, 2, 10, 50 or 100 µM, followed by a concentration of 250 µM (n = 4–6 for each concentration; fig. 4A). The charge of the GABACR-mediated component of glu-evoked responses was normalized to the size of the baseline GABACR response and plotted versus picrotoxin concentration (fig. 4D). A fit of the dose-response plot with a Hill equation gave an IC50 value of 1.4 µM.

Figure 4. Picrotoxin-sensitivity of GABACR currents.

A, Example GABACR responses evoked by local application of L-glutamate (glu; 100 µM, 10 ms) to activate reciprocal amacrine cell synapses, and their inhibition by picrotoxin. Three individual responses (grey) and the mean response (black) are shown for each condition. B, An example experiment showing inhibition of the tonic GABACR current by the same concentrations of picrotoxin, following potentiation of the current by NO-711 (3 µM). C, Example average GABACR-mediated mIPSCs during baseline and following application of NO-711 (3 µM), with mean data for average mIPSC charge under these conditions (n = 4). GABACR mIPSCs were recorded in Ca2+-free extracellular solution to facilitate their detection, in the presence of bicuculline. D, Dose-response curves for picrotoxin inhibition of glu-evoked (n = 4–6) and tonic (n = 3–6) GABACR currents, fit with Hill equations to give IC50 values.

To determine the picrotoxin-sensitivity of the tonic GABACR current, it was first potentiated by application of NO-711 (3 µM) [4]. NO-711 appears to exert its effects solely via inhibition of GABA uptake rather than via any direct action on GABACRs, as GABACR-mediated mIPSCs [5] are not affected by application of NO-711 (fig. 4C). Following the establishment of a stable baseline tonic current in NO-711, picrotoxin was applied at a concentration of 0.5, 2, 10, 50, 100 or 200 µM, followed by a maximal concentration of 250 µM (n = 3-6 for each concentration; fig. 4B). The amplitude of the GABACR-mediated tonic current was normalized to the baseline current and plotted versus picrotoxin concentration (fig. 4D). A fit of the dose-response plot with a Hill equation gave an IC50 value of 8.5 µM. The amount of inhibition of the tonic GABACR current was statistically different from that of glu-evoked GABACR currents at picrotoxin concentrations between 0.5 µM and 50 µM (P<0.05). The approximately 6-fold difference in picrotoxin sensitivity suggests that homomeric ρ1 receptors may contribute more to the tonic GABACR current than to synaptic GABACR currents.

GABACR subunit composition: Cyclothiazide-sensitivity

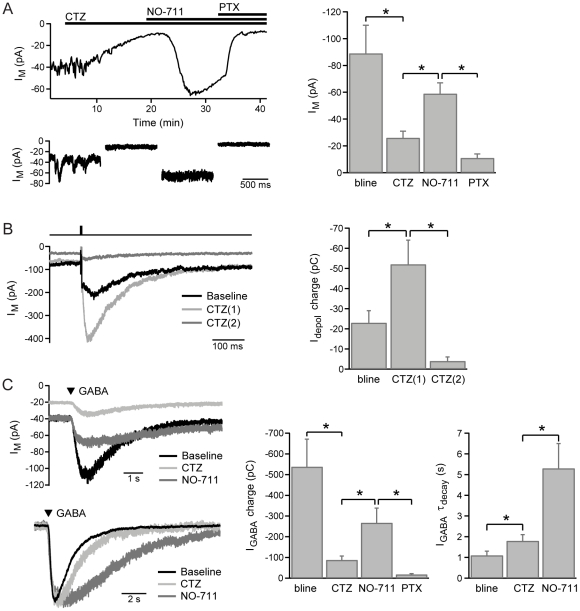

Cyclothiazide has recently been shown to be a selective inhibitor of ρ2 receptors, acting as a non-competitive antagonist with an IC50 of ∼12 µM. At a concentration of 300 µM, cyclothiazide abolishes GABA responses mediated by ρ2 homomers but has no significant effect on the responses of ρ1 homomers [42]. We therefore examined the effect of cyclothiazide on GABACR-mediated currents in BCTs. Bath-application of cyclothiazide (300 µM), in the presence of bicuculline (50 µM), significantly reduced the amplitude of the holding current (n = 10), and also reduced the spontaneous fluctuations of this current (fig. 5A). Synaptic feedback currents evoked by brief BCT depolarization (to −10 mV for 5 ms) were initially potentiated during cyclothiazide wash-on, as observed previously [43], due to the activity of cyclothiazide as an inhibitor of AMPA receptor desensitization. However, the feedback currents were subsequently virtually eliminated (n = 8; fig. 5B), although it is likely that run-down of BCT exocytosis contributed to the feedback current reduction [26]. GABACR currents evoked by local application of GABA (100 µM, 50–100 ms) were also significantly reduced by cyclothiazide, but not completely eliminated (n = 7; fig. 5C). GABA-evoked responses had a slower rate of decay in the presence of cyclothiazide than in control conditions (n = 7; fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Cyclothiazide-sensitivity of GABACR-currents.

A, Example experiment showing the effect of cyclothiazide (CTZ; 300 µM) on the holding current, with subsequent application of NO-711 (3 µM) and picrotoxin (250 µM), with mean data for these experiments (n = 10). B, Example synaptic feedback currents evoked by brief BCT depolarization (to −10 mV for 5 ms) during wash-on of cyclothiazide, and mean data showing the biphasic effect of cyclothiazide on the charge of feedback responses (n = 8). CTZ(1) was measured 3–4 mins after application, CTZ(2) was measured 6–8 mins after application. C, Example GABA-evoked responses (100 µM, 50–100 ms) showing the effects of cyclothiazide and NO-711 on response amplitude (top) and kinetics (bottom, peak-scaled responses from a different experiment), with mean data (n = 7) for the charge and decay time-constant of GABA-evoked responses under these conditions.

To further investigate the remaining cyclothiazide-resistant tonic and GABA-evoked currents, NO-711 (3 µM) was applied in the continuing presence of cyclothiazide. NO-711 increased the holding current (n = 10), which was subsequently inhibited by application of picrotoxin (200–250 µM; fig. 5A). In addition, NO-711 significantly increased the charge and slowed the decay of responses evoked by exogenous GABA (n = 7; fig. 5C). These results support the view that the majority of BCT GABACRs are ρ1-ρ2 heteromers, but provide evidence that a population of homomeric ρ1 receptors contributes to the tonic current.

Discussion

The aim of the current experiments was to further our understanding of two unknown properties of the tonic GABACR current in BCTs: the non-vesicular source of GABA for activating the current and the identity of the receptors mediating the current. Following recent reports of non-vesicular GABA release via Best1 anion channels [12], we tested the effects of anion channel inhibitors on the tonic GABACR current. The results indicate that the GABA release mechanism is insensitive to NPPB and FFA but sensitive to DIDS. All three drugs inhibited to some extent the activity of GABA transporters, as evidenced by the potentiation of tonic, GABA-evoked and synaptic feedback currents mediated by GABACRs. In addition, NPPB and FFA exerted effects on intact BCs via inhibition of hemichannels, and DIDS was found to inhibit GABAAR-mediated sIPSCs. However, there appeared to be no direct inhibitory effect of NPPB, FFA or DIDS on GABACRs.

There is increasing evidence for the release of neurotransmitters, in particular glutamate and ATP, from astrocytes [44], [45]. GABA is also known to be released from astrocytes in the hippocampus, cerebellum, thalamus and olfactory bulb, with consequent activation of neuronal GABAARs [12], [46]-[48]. Astrocytes release ‘gliotransmitters’ via several mechanisms including Ca2+-dependent vesicular exocytosis, reversal of transporters, and release via hemichannels, ionotropic purinergic receptors and anion channels [49]. Various different types of anion channel have been implicated in gliotransmitter release including volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs) [15] and more recently Ca2+-activated anion channels such as Best1, which are present in hippocampal and cerebellar astrocytes, and which can mediate tonic GABA release [12], [13].

Distinguishing pharmacologically between mechanisms of non-vesicular release and between different types of Cl- channel is challenging due to the cross-reactivity of commonly-used anion channel inhibitors with other release mechanisms, for example the block of hemichannels by NPPB [50], and due to the lack of selectivity of inhibitors between Cl- channel classes [51]. However, the insensitivity of the tonic GABACR current to carbenoxolone, PPADS and Brilliant Blue G [11], and to NPPB and FFA indicates that hemichannels, P2X7 receptors, VRACs and Best1 anion channels are not major contributors to the non-vesicular GABA release that activates this current. Reversal of GABA transporters also does not seem to be involved [11]. The non-vesicular release of GABA in the cerebellum that activates a tonic GABAAR current in granule cells was similarly found to be independent of GABA transporter reversal and VRACs, and to be potentiated rather than inhibited by NPPB [8].

The tonic GABACR current in BCTs was significantly inhibited by DIDS, but the identity of the DIDS-sensitive anion channel or exchanger that mediates tonic GABA release in the retina is not known. Interestingly, a similar NPPB-resistant but DIDS-sensitive mechanism underlies the tonic release of glutamate in the hippocampus [33]. One potential candidate is a type a large-conductance Cl- channel (maxi-Cl-) that was identified in drosophila and has three mammalian homologs that are activated by either Ca2+ or cell swelling, which is sensitive to DIDS but resistant to niflumic acid [52]. In the current experiments, DIDS failed to completely block the tonic GABACR current in BCTs, even in Ca2+-free extracellular solution, suggesting that either DIDS at this concentration does not completely block the non-vesicular release mechanism, or it blocks only one of two or more contributing mechanisms. Alternatively, in the presence of DIDS the release of GABA may be blocked but, due to the additional action of DIDS as an inhibitor of GABA uptake, the ambient extracellular GABA concentration remains sufficient to evoke some tonic GABACR current.

The cellular source of GABA for activating the tonic GABACR current in BCTs is also unknown, but the most likely sources are amacrine cells and Müller cells. BCTs are surrounded by amacrine cell processes that make the conventional GABAergic synapses that mediate reciprocal and lateral feedback inhibition [53]. Although non-vesicular neurotransmitter release is thought to occur primarily from glial cells, DIDS-sensitive GABA-permeable anion channels have been observed in Deiters neurons in the brainstem [54]. Müller cells, the principle glial cells of the retina, are known to release neuroactive substances such as ATP, with consequent effects on synaptic activity and spiking in ganglion cells [55].

The tonic activation of membrane conductances as a result of non-vesicular neurotransmitter release may be a general feature of neuronal function in the CNS, involving not only inhibitory but also excitatory receptor systems. For example, the non-vesicular release of glutamate from astrocytes evokes a tonic NMDA receptor current in hippocampal neurons [33], [56]–[58]. A common feature of GABAergic and glutamatergic tonic currents is their potentiation by inhibition of neurotransmitter uptake, which may provide an endogenous regulatory system for controlling the magnitude of the current and its consequent effects on neuronal excitability [1].

BCs express both ρ1 and ρ2 GABACR subunits, which readily form heteromeric receptors, and it is likely that most BC GABACRs are ρ1-ρ2 heteromers [22], [23], [59]-[61]. However, the additional expression of homomeric receptors would extend the functional diversity of GABACR-mediated inhibition, as receptor properties are dependent on ρ subunit composition. Each ρ subunit has a similar structure to other members of the Cys-loop superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels [62]. Amino-acid substitutions in the pore-forming second transmembrane domain, in particular a switch at the 2′ position from proline in ρ1 to serine in ρ2, underlies subunit differences in properties such as deactivation rate, channel conductance and sensitivity to GABA [24], [63], [64]. This amino-acid substitution also underlies the difference in sensitivity to both picrotoxin and cyclothiazide of ρ1 and ρ2 receptors [41], [42].

We initially investigated the subunit composition of GABACRs in BCTs by comparing the picrotoxin-sensitivity of glu-evoked and tonic GABACR currents. Glu-evoked currents, designed to predominantly activate synaptic GABACRs, were more sensitive to picrotoxin than the tonic GABACR current, with IC50 values of 1.4 µM and 8.5 µM respectively. When expressed in heterologous systems, perch ρ1A and ρ1B homomeric receptors have reported IC50 values for picrotoxin inhibition of 10 µM and 56 µM, compared with 2 µM for ρ2A and ρ2B homomers [21], [23]. Heteromeric ρ1B/ρ2A receptors exhibit a similar sensitivity to ρ2 homomers when the ρ subunits are expressed at a 1∶1 ratio (IC50 value of 3 µM) [23]. A similar difference has been reported for human ρ subunits (eg. IC50 values of 48 µM for ρ1 and 5 µM for ρ2 homomeric receptors), with heteromeric receptors having an intermediate sensitivity [22], [41]. The subunit-specific differences in picrotoxin sensitivity are most pronounced in the presence of relatively high GABA concentrations (10–30 µM), due to a competitive component in the inhibition of ρ1 receptors [41]. The difference in picrotoxin sensitivity of the tonic and synaptic GABACR currents in BCTs suggests that these currents may be mediated by different (though probably overlapping) populations of GABACRs, with a greater contribution of ρ1 receptors to the tonic current.

In addition we investigated the effect of cyclothiazide, which has recently been shown to be a selective inhibitor of ρ2 subunits [42]. Cyclothiazide reduced the amplitude of the tonic current, inhibited synaptic feedback currents and reduced the size of GABA-evoked responses, consistent with most BCT GABACRs being ρ1-ρ2 heteromers. The reduction in the amplitude and spontaneous fluctuations of the tonic current by cyclothiazide is similar to that observed with application of Ca2+-free solution [11], suggesting that the summation of slow IPSCs evoked by spontaneous synaptic release activating heteromeric GABACRs contributes to the tonic current in BCTs [5]. Spontaneous GABA release occurs at a high rate at amacrine cell to BCT synapses in retinal slices, as evidenced by the high frequency of GABAAR-mediated sIPSCs observed in the absence of bicuculline [11] (fig. 3). In the presence of bicuculline, synaptic GABA release and the tonic GABACR current tend to be potentiated due to amacrine cell disinhibition [6].

However, a small constant tonic current remained in the presence of 300 µM cyclothiazide that was potentiated by inhibition of GABA uptake and is likely to be mediated by homomeric ρ1 receptors [42]. Small GABA-evoked currents were also observed in the presence of cyclothiazide that were potentiated by NO-711 and inhibited by picrotoxin. The slower decay rate of GABA-evoked currents in cyclothiazide compared with control conditions is consistent with reports of subunit-specific kinetics. For example, the deactivation rate of homomeric ρ1 receptors is slower than for ρ1-ρ2 heteromers, with respective time-constants of 14 s and 9 s for human subunits, and 234 s and 75 s for perch subunits (B form) [22], [23]. The change in decay kinetics also provides evidence against an incomplete block of heteromeric GABACRs by cyclothiazide. The lack of desensitization of BCT GABACRs [4] and the slow deactivation of ρ1 subunits are both likely to contribute to the very slow decay rate of GABA-evoked responses in the absence of GABA uptake (fig. 5). These properties, combined with a high affinity for GABA [21], [22], make homomeric ρ1 receptors particularly suitable for mediating a tonic current in BCTs.

Given the lack of dependence on vesicular release of the tonic GABACR current [11], it is likely that the population of homomeric ρ1 receptors that contributes to this current is located extrasynaptically. An analogous situation is found in central neurons, where tonic GABAAR currents are mediated by extrasynaptic receptors [16]. Fluorescence imaging of immunolabeled ρ subunits in BCTs has shown ‘punctate’ labeling in several species including goldfish, with labeling within the synaptic cleft at the electron microscope level [65]–[68], reflecting the synaptic localization of heteromeric receptors that mediate GABACR feedback currents and spontaneous IPSCs. However, it has been noted that rat BCTs also exhibit diffuse extrasynaptic ρ subunit labeling [68], which may correspond with a population of homomeric ρ1 receptors that contributes to the tonic current. Identification of the subcellular localization of GABACR subunits in BCTs, and mechanisms that target specific receptors to synaptic or extrasynaptic sites, requires further investigation. In addition, it will be interesting to determine whether synaptic and extrasynaptic GABACRs are differentially regulated, and the relative importance of factors such as changes in receptor number or properties, or in the rates of GABA release and uptake, in modulating synaptic and tonic forms of GABACR-mediated inhibition in BCTs.

In summary, these experiments indicate that tonic GABACR currents in BCTs are activated by GABA released, in part, via a DIDS-sensitive mechanism, and that homomeric ρ1 receptors contribute to this current. Tonic inhibition regulates the ability of BCTs to fire Ca2+-dependent action potentials [4], and is likely to modulate the transmission of light responses to ganglion cells. However, how this form of inhibition interacts with synaptic GABAAR and GABACR-mediated inhibition, and with the multiple additional forms of synaptic feedback that exist in BCTs, in the processing of visual information in the retina remains to be determined.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was funded by a Medical Research Council New Investigator Research Grant (ID 86420, www.mrc.ac.uk). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Glykys J, Mody I. Activation of GABAA receptors: views from outside the synaptic cleft. Neuron. 2007;56:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semyanov A, Walker MC, Kullmann DM, Silver RA. Tonically active GABAA receptors: modulating gain and maintaining the tone. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull C, Li GL, von Gersdorff H. GABA transporters regulate a standing GABAC receptor-mediated current at a retinal presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6979–6984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1386-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer MJ. Functional segregation of synaptic GABAA and GABAC receptors in goldfish bipolar cell terminals. J Physiol. 2006;577:45–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Multiple pathways of inhibition shape bipolar cell responses in the retina. Vis Neurosci. 2011;28:95–108. doi: 10.1017/S0952523810000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wall MJ, Usowicz MM. Development of action potential-dependent and independent spontaneous GABAA receptor-mediated currents in granule cells of postnatal rat cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi DJ, Hamann M, Attwell D. Multiple modes of GABAergic inhibition of rat cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 2003;548:97–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Wang W, Richerson GB. Vigabatrin induces tonic inhibition via GABA transporter reversal without increasing vesicular GABA release. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2021–2034. doi: 10.1152/jn.00856.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Wang W, Richerson GB. The transmembrane sodium gradient influences ambient GABA concentration by altering the equilibrium of GABA transporters. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2425–2436. doi: 10.1152/jn.00545.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones SM, Palmer MJ. Activation of the tonic GABAC receptor current in retinal bipolar cell terminals by nonvesicular GABA release. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:691–699. doi: 10.1152/jn.00285.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Yoon BE, Berglund K, Oh SJ, Park H, et al. Channel-mediated tonic GABA release from glia. Science. 2010;330:790–796. doi: 10.1126/science.1184334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park H, Oh SJ, Han KS, Woo DH, Park H, et al. Bestrophin-1 encodes for the Ca2+-activated anion channel in hippocampal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13063–13073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3193-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Driscoll KE, Leblanc N, Hatton WJ, Britton FC. Functional properties of murine bestrophin 1 channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA. VRACs CARVe a path for novel mechanisms of communication in the CNS. Sci STKE 2006. 2006:e42. doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006pe42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belelli D, Harrison NL, Maguire J, Macdonald RL, Walker MC, et al. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors: form, pharmacology, and function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12757–12763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheleznova NN, Sedelnikova A, Weiss DS. Function and modulation of delta-containing GABA(A) receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S67–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Delgado G, Estrada-Mondragon A, Miledi R, Martinez-Torres A. An update on GABA rho receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:422–433. doi: 10.2174/157015910793358141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D, Pan ZH, Awobuluyi M, Lipton SA. Structure and function of GABA(C) receptors: a comparison of native versus recombinant receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Y, Qian H. Interactions between rho and gamma2 subunits of the GABA receptor. J Neurochem. 2005;94:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian H, Dowling JE, Ripps H. Molecular and pharmacological properties of GABA-rho subunits from white perch retina. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:305–320. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19981105)37:2<305::aid-neu9>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enz R, Cutting GR. GABAC receptor rho subunits are heterogeneously expressed in the human CNS and form homo- and hetero-oligomers with distinct physical properties. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:41–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y, Ripps H, Qian H. Random assembly of GABA rho1 and rho2 subunits in the formation of heteromeric GABAC receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:289–305. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Y, Ripps H, Qian H. A single amino acid in the second transmembrane domain of GABA rho receptors regulates channel conductance. Neurosci Lett. 2007;418:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li GL, Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. Short-term depression at the reciprocal synapses between a retinal bipolar cell terminal and amacrine cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7377–7385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer MJ, Taschenberger H, Hull C, Tremere L, von Gersdorff H. Synaptic activation of presynaptic glutamate transporter currents in nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4831–4841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04831.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karakossian MH, Spencer SR, Gomez AQ, Padilla OR, Sacher A, et al. Novel properties of a mouse gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter (GAT4). J Membr Biol. 2005;203:65–82. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0732-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eskandari S, Zampighi GA, Leung DW, Wright EM, Loo DD. Inhibition of gap junction hemichannels by chloride channel blockers. J Membr Biol. 2002;185:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye ZC, Oberheim N, Kettenmann H, Ransom BR. Pharmacological “cross-inhibition” of connexin hemichannels and swelling activated anion channels. Glia. 2009;57:258–269. doi: 10.1002/glia.20754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ripps H, Qian H, Zakevicius J. Properties of connexin26 hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2004;24:647–665. doi: 10.1023/B:CEMN.0000036403.43484.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stout CE, Costantin JL, Naus CC, Charles AC. Intercellular calcium signaling in astrocytes via ATP release through connexin hemichannels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10482–10488. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai I, Tanaka M, Tachibana M. Active roles of electrically coupled bipolar cell network in the adult retina. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9260–9270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1590-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavelier P, Attwell D. Tonic release of glutamate by a DIDS-sensitive mechanism in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 2005;564:397–410. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.082131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corey JL, Guastella J, Davidson N, Lester HA. GABA uptake and release by a mammalian cell line stably expressing a cloned rat brain GABA transporter. Mol Membr Biol. 1994;11:23–30. doi: 10.3109/09687689409161026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosower EM. A partial structure for the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor is derived from the model for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. The anion-exchange protein of cell membranes is related to the GABAA receptor. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson S, Toth L, Sheth B, Sur M. Orientation selectivity of cortical neurons during intracellular blockade of inhibition. Science. 1994;265:774–777. doi: 10.1126/science.8047882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollrigel GS, Ross ST, Soltesz I. Temporal patterns and depolarizing actions of spontaneous GABAA receptor activation in granule cells of the early postnatal dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2340–2351. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz A, Campanac E, Scott RS, Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. Presynaptic GABAA receptors enhance transmission and LTP induction at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:431–438. doi: 10.1038/nn.2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews G, Neher E, Penner R. Chloride conductance activated by external agonists and internal messengers in rat peritoneal mast cells. J Physiol. 1989;418:131–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kokubun S, Saigusa A, Tamura T. Blockade of Cl channels by organic and inorganic blockers in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1991;418:204–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00370515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang TL, Hackam AS, Guggino WB, Cutting GR. A single amino acid in gamma-aminobutyric acid rho 1 receptors affects competitive and noncompetitive components of picrotoxin inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11751–11755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie A, Song X, Ripps H, Qian H. Cyclothiazide: a subunit-specific inhibitor of GABAC receptors. J Physiol. 2008;586:2743–2752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. Prolonged reciprocal signaling via NMDA and GABA receptors at a retinal ribbon synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11412–11423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2203-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parpura V, Zorec R. Gliotransmission: Exocytotic release from astrocytes. Brain Res Rev. 2010;63:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamilton NB, Attwell D. Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrn2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu QY, Schaffner AE, Chang YH, Maric D, Barker JL. Persistent activation of GABA(A) receptor/Cl(-) channels by astrocyte-derived GABA in cultured embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1392–1403. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jimenez-Gonzalez C, Pirttimaki T, Cope DW, Parri HR. Non-neuronal, slow GABA signalling in the ventrobasal thalamus targets delta-subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1471–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozlov AS, Angulo MC, Audinat E, Charpak S. Target cell-specific modulation of neuronal activity by astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10058–10063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603741103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malarkey EB, Parpura V. Mechanisms of glutamate release from astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evanko DS, Zhang Q, Zorec R, Haydon PG. Defining pathways of loss and secretion of chemical messengers from astrocytes. Glia. 2004;47:233–240. doi: 10.1002/glia.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki M, Morita T, Iwamoto T. Diversity of Cl(-) channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:12–24. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki M, Mizuno A. A novel human Cl(-) channel family related to Drosophila flightless locus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22461–22468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marc RE, Liu W. Fundamental GABAergic amacrine cell circuitries in the retina: nested feedback, concatenated inhibition, and axosomatic synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:560–582. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001002)425:4<560::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rapallino MV, Cupello A. GABA and chloride permeate via the same channels across single plasma membranes microdissected from rabbit Deiters' vestibular neurones. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:231–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newman EA. A dialogue between glia and neurons in the retina: modulation of neuronal excitability. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:245–252. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0500013X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jabaudon D, Shimamoto K, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Scanziani M, Gahwiler BH, et al. Inhibition of uptake unmasks rapid extracellular turnover of glutamate of nonvesicular origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8733–8738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Le Meur K, Galante M, Angulo MC, Audinat E. Tonic activation of NMDA receptors by ambient glutamate of non-synaptic origin in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;580:373–383. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fellin T, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Purinergic receptors mediate two distinct glutamate release pathways in hippocampal astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4274–4284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Hartveit E, Wassle H, Bormann J. Expression of GABA receptor rho 1 and rho 2 subunits in the retina and brain of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1495–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeh HH, Grigorenko EV, Veruki ML. Correlation between a bicuculline-resistant response to GABA and GABAA receptor rho 1 subunit expression in single rat retinal bipolar cells. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13:283–292. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800007525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang D, Pan ZH, Zhang X, Brideau AD, Lipton SA. Cloning of a gamma-aminobutyric acid type C receptor subunit in rat retina with a methionine residue critical for picrotoxinin channel block. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11756–11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian H, Ripps H. Focus on molecules: the GABAC receptor. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:1002–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carland JE, Moore AM, Hanrahan JR, Mewett KN, Duke RK, et al. Mutations of the 2′ proline in the M2 domain of the human GABAC rho1 subunit alter agonist responses. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:770–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qian H, Dowling JE, Ripps H. A single amino acid in the second transmembrane domain of GABA rho subunits is a determinant of the response kinetics of GABAC receptors. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:67–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199907)40:1<67::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Wassle H, Bormann J. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAC receptor rho subunits in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4479–4490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koulen P, Brandstatter JH, Kroger S, Enz R, Bormann J, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAC receptor rho subunits in the cat, goldfish, and chicken retina. J Comp Neurol. 1997;380:520–532. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970421)380:4<520::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fletcher EL, Koulen P, Wassle H. GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:351–365. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980706)396:3<351::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koulen P, Brandstatter JH, Enz R, Bormann J, Wassle H. Synaptic clustering of GABAC receptor rho-subunits in the rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:115–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]