Abstract

Misrepair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) produced by the V(D)J recombinase (the RAG1/RAG2 proteins) at immunoglobulin (Ig) and T cell receptor (Tcr) loci has been implicated in pathogenesis of lymphoid malignancies in humans1 and in mice2–7. Defects in DNA damage response factors such as ATM and combined deficiencies in classical nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and p53 predispose to RAG-initiated genomic rearrangements and lymphomagenesis2–11. Although we showed previously that RAG1/RAG2 shepherd the broken DNA ends to classical NHEJ for proper repair12,13, roles for the RAG proteins in preserving genomic stability remain poorly defined. Here we show that the RAG2 C-terminus, although dispensable for recombination14,15, is critical for maintaining genomic stability. Thymocytes from “core” Rag2 homozygotes (Rag2c/c mice) show dramatic disruption of Tcrα/δ locus integrity. Furthermore, all Rag2c/c p53−/− mice, unlike Rag1c/c p53−/− and p53−/− animals, rapidly develop thymic lymphomas bearing complex chromosomal translocations, amplifications, and deletions involving the Tcrα/δ and Igh loci. We also find these features in lymphomas from Atm−/− mice. We show that, like ATM-deficiency3, core RAG2 severely destabilizes the RAG post-cleavage complex. These results reveal a novel genome guardian role for RAG2 and suggest that similar “end release/end persistence” mechanisms underlie genomic instability and lymphomagenesis in Rag2c/c p53−/− and Atm−/− mice.

RAG mutations can cause specific defects in the joining stage of V(D)J recombination12,13,16. The “dispensable” RAG2 C-terminus (murine amino acids 1–383) is of particular interest: Loss of the RAG2 C-terminus impairs joining of substrates17, increases levels of DSBs17 that persist through the cell cycle18, and increases accessibility of the broken DNA ends to alternative NHEJ12,19. Despite these defects, Rag2c/c mice are not lymphoma-prone.

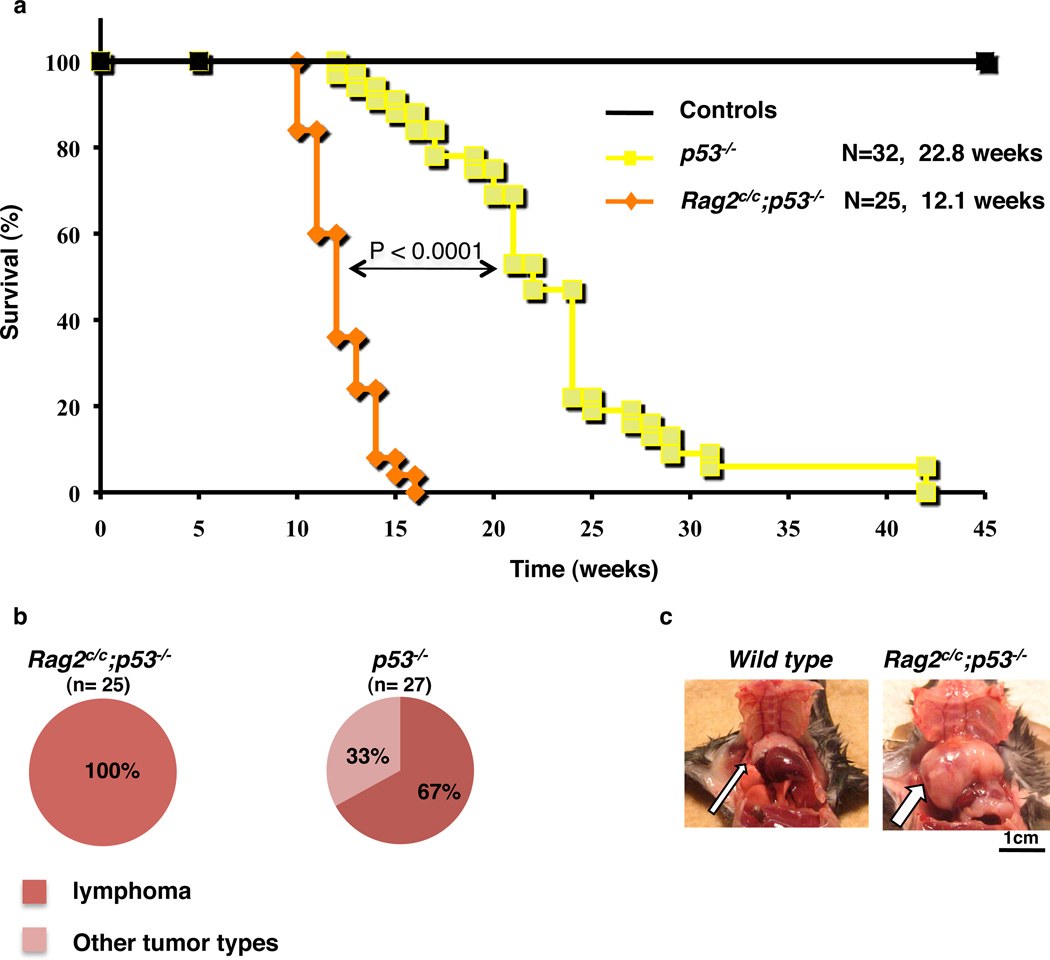

We reasoned that Rag2c/c p53−/− double mutant mice might display genomic instability and lymphomagenesis, even in the context of intact classical NHEJ. Consistent with previous reports15, our Rag2c/c mice displayed partial developmental blocks in B and T lymphopoiesis because of a selective V-to-DJ rearrangement defect (Supplementary Fig. 1). Rag2c/c animals, observed for up to one year, showed no obvious signs of tumorigenesis (Fig. 1a and data not shown). As expected20, approximately two-thirds of p53−/− mice developed thymic lymphoma at an average age of ≈ 23 weeks (mean survival = 22.8 weeks) (Fig. 1a, b). Similar findings in RAG/p53 deficient mice21 demonstrate that RAG-initiated DSBs are not critical initiators of lymphomagenesis in p53-deficient mice. In sharp contrast, 100% (n = 25) of our Rag2c/c p53−/− mice died within 16 weeks (mean survival = 12.1 weeks) with aggressive thymic lymphomas (Fig. 1a, b, c). Tumor cells were highly proliferative and expressed cell surface CD4 and CD8 (Supplementary Fig. 2), with little or no surface TCR (CD3ε or TCRβ) (data not shown), indicating that these tumors originate from immature thymocytes. Tumors with highly proliferating lymphoblasts were detected in 4- to 6-week-old Rag2c/c p53−/− thymi, but not in other organs (data not shown), confirming their thymic origin. Rag2c/c p53−/− tumors generally displayed one or a few predominant Dβ1-Jβ1 or Dβ2-Jβ2 rearrangements, indicating a clonal or oligoclonal origin (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1. The C-terminus of RAG2 is a tumor suppressor in developing thymocytes.

a. Kaplan-Meier tumor-free survival analysis for cohorts of control (WT, n=12 and Rag2c/c, n=19), p53−/− (n=32) and Rag2c/c p53−/− (n=25) mice. Animals were monitored for 50 weeks. The average age of death in weeks is shown for p53−/− (22.8 weeks) and Rag2c/c p53−/− (12.1 weeks) genotypes with the P-value determined by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. b. Pie chart showing the tumor spectrum observed for Rag2c/c p53−/− (n=25) and p53−/− mice (n=27). All Rag2c/c p53−/− animals (n=25) showed enlarged thymus. p53−/− animals showed either enlarged thymus and/or spleen (n=18) or other non lymphoid tumor mass (n=9). c. Physical appearance of normal thymus (wild type) and thymic lymphoma (Rag2c/c p53−/−, arrow) of 3-month-old animals.

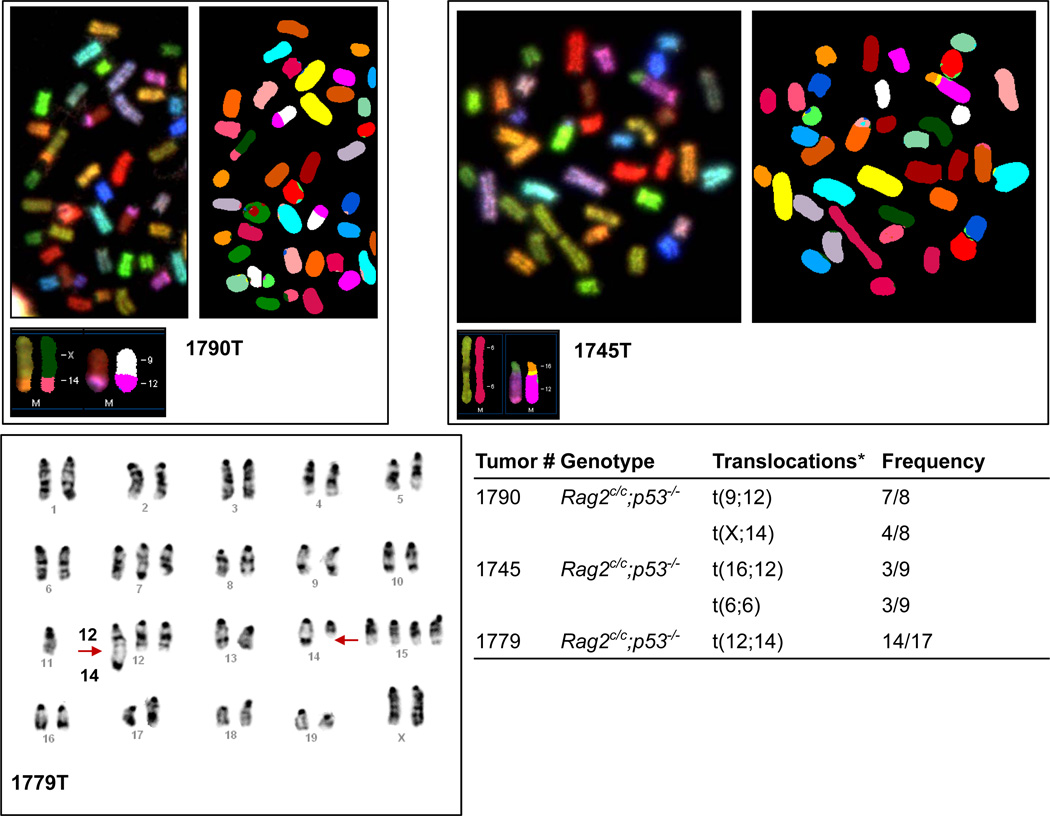

We next examined genomic stability in lymphomas from Rag2c/c p53−/− mice, first by analysis of Giemsa stained metaphase spreads prepared from 12 Rag2c/c p53−/− and two p53−/− thymic lymphomas (Supplementary Table 1). Wild-type thymocytes showed almost no abnormal metaphases (0% to 3%) (Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, p53−/− and Rag2c/c p53−/− tumors harbored a variety of cytogenetic aberrations (aberrant metaphases: 8% to 94%), including aneuploidy, chromosome breaks, and chromosome fusions (Supplementary Table 1). We analyzed three Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas using spectral (1790T and 1745T) and G-band (1779T) karyotyping (Fig. 2). We observed recurrent translocations involving chromosomes that harbor Tcr (Chr. 14 and 6) and Ig (Chr. 12, 6 and 16) loci, suggesting that these might have been initiated by RAG-generated breaks. Moreover, all three lymphomas harbored translocations of the Igh locus-containing chromosome 12 and/or the Tcrα/δ locus-containing chromosome 14, loci which rearrange in thymocytes22. Analysis of lymphoma 1779T revealed a C12;14 translocation (Fig. 2). These results suggest that Rag2c/c p53−/− T cell tumors harbor clonal translocations involving the Tcrα/δ and Igh loci, as seen in T cell lymphomas from ataxia-telangiectasia patients and Atm−/− mice7,8,10,11, rearrangements not observed in p53−/− lymphomas21,23.

Figure 2. Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas display recurrent translocations involving chromosomes that harbor antigen-receptor loci.

Representative images of spectral karyotyping (1790T and 1745T) and G-band karyotyping (1779T) analysis of three Rag2c/c p53−/− T cell lymphomas. Metaphase number analyzed and translocations for each tumor sample are listed in the table.*All three tumors harbor clonal translocations involving chromosomes that carry Tcr (Chr.14: Tcrα/δ; Chr.6:Tcrβ) and/or Ig (Chr.12:Igh; Chr.6:Igκ; Chr.16:Igλ) loci.

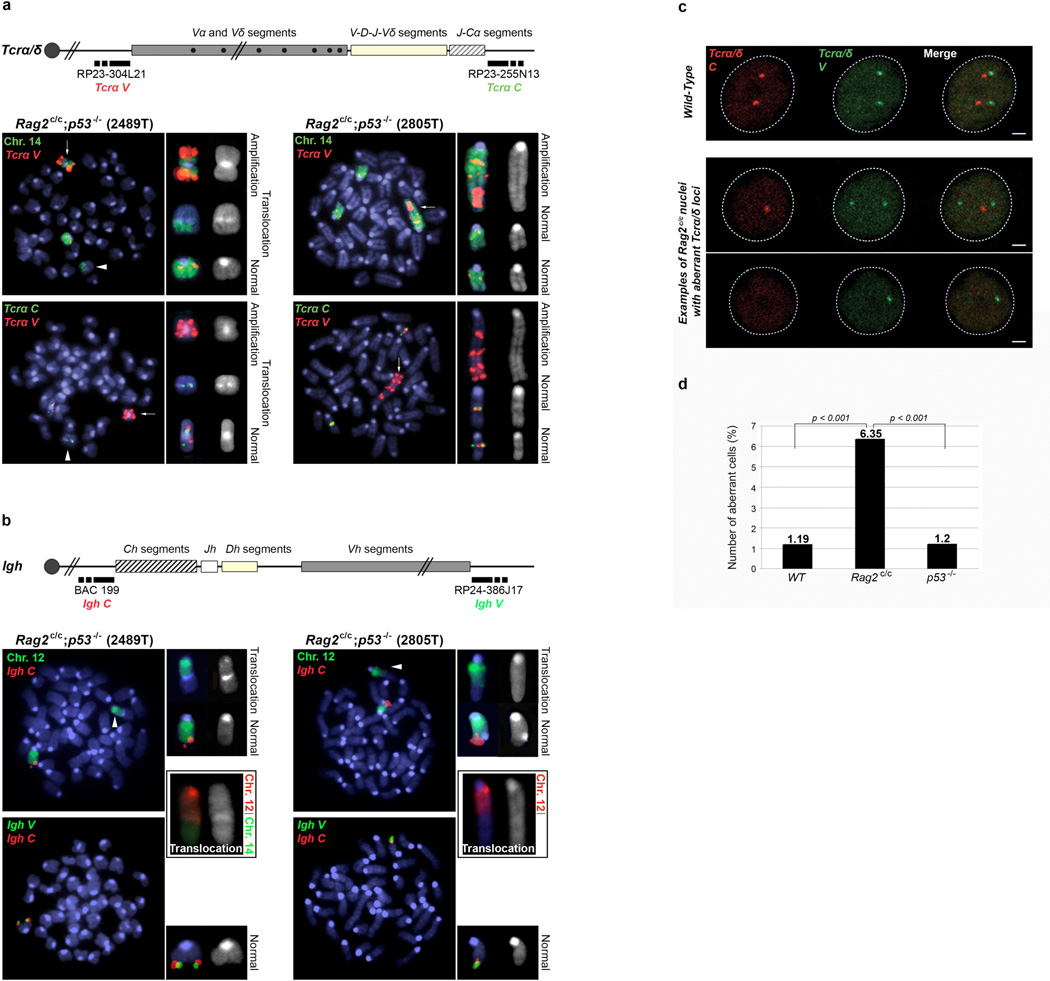

To confirm the involvement of the Tcrα/δ locus in chromosome translocations, we performed DNA-fluorescent in situ hybridization (DNA-FISH) analyses on metaphases from Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas (2489T and 2805T) using probes centromeric (Tcrα/δ V) and telomeric (Tcrα/δ C) to the Tcrα/δ locus plus a paint for chromosome 14 (Fig. 3a). In both tumors, breakpoints within the Tcrα/δ locus of one of the two chromosomes 14 resulted in amplification of the Tcrα/δ V region (Fig. 3a). The telomeric fragment (including Tcrα/δ C) was either translocated (2489T), or lost (2805T) (Fig. 3a). DNA-FISH analysis of tumors 1790T and 1779T (from Fig. 2) using Tcrα/δ C and V probes also confirmed translocation of chromosome 14 with breakpoints within the Tcrα/δ locus, although without obvious amplification (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Rag2c/c p53−/− thymocytes displayTcrα/δ and Igh-associated genomic instability.

a. Top panel: schematic of the Tcrα/δ locus, with positions of the BACs used for generation of DNA FISH probes indicated. Bottom panels: representative metaphases from two Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas using the Tcrα/δ V BAC probe (red signal) combined with chromosome 14 paint (green signal, top row) or with the Tcrα/δ C BAC probe (green signal, bottom row). Arrows point the amplification of the Tcrα/δ V region, arrow heads point the translocated chromosome 14. b. Top panel: schematic of the Igh locus, with positions of the BACs used for generation of DNA FISH probes indicated. Bottom panels: representative metaphases from the same two Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas using the Igh C BAC probe (red signal) combined with chromosome 12 paint (green signal, top row), or with the Igh V BAC probe (green signal, bottom row). Combination of chromosome 12 (red) and chromosome 14 (green) paints is shown for both tumors in black boxes. Arrow heads point the translocated chromosome 12. c. Examples of confocal sections of three-dimensional Tcrα/δ DNA FISH on freshly isolated wild-type (top row) or Rag2c/c (bottom rows) double positive thymocytes. Tcrα/δ V (Green) and C (Red) BAC probes were used. Scale bar = 1µm. d. Representative experiment showing the frequency at which Tcrα/δ V and/or Tcrα/δ C signals are lost in wild-type, p53−/− and Rag2c/c thymocytes (n>200, see Supplementary Fig. 11 for additional experiments and statistical analysis).

We next performed DNA-FISH on Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas 2489T and 2805T using probes centromeric (Igh C) and telomeric (Igh V) to the Igh locus along with a chromosome 12 paint (Fig. 3b). In both lymphomas, one chromosome 12 showed translocation with another chromosome, with accompanying loss of both Igh C and V signals (Fig. 3b). This could result from RAG-induced breaks with loss of the telomeric end of the chromosome (including Igh V) and loss of the Igh C region by end degradation before fusion to the partner chromosome, as previously reported in Atm−/− mouse T cells8. Moreover, dual chromosome 12 and 14 paint analysis showed a C12;14 translocation in lymphoma 2489T (Fig 3b). In contrast to Rag2c/c p53−/− lymphomas, DNA-FISH on metaphases from one p53−/− thymic lymphoma (6960T) indicated that both Tcrα/δ and Igh loci were intact (Supplementary Fig. 5), consistent with previous work21.

We next performed array-based comparative genomic hybridization (a-CGH) analysis on genomic DNA from five Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas (2489T, 2805T, 1348T, 1779T, 1780T). We observed loss or gain of a region within the Tcrα/δ and Igh loci, reflecting V(D)J recombination (Supplementary Fig. 6). All five Rag2c/c p53−/− lymphomas examined showed substantial amplification of a common region on chromosome 14, centromeric of the Tcrα/δ locus (Supplementary Fig. 6a), in agreement with our FISH analyses (Fig. 3a). We also observed loss of a common region on chromosome 12, telomeric of the Igh locus in all five Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Tumors 1779T, 2489T and 2805 also showed loss of a large region centromeric of the Igh locus, likely reflecting DNA-end degradation before fusion to the partner chromosome (Fig. 2; Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Fig. 6b). In contrast, aCGH analysis of p53−/− thymic lymphoma 6960T failed to reveal amplification centromeric to the Tcrα/δ locus or deletion telomeric to the Igh locus (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b), in agreement with our FISH analysis (Supplementary Fig. 5) and previous data23.

Blocking lymphocyte development in early stages can lead to persistent RAG activity, which, in the absence of p53, can provoke lymphomagenesis23. To investigate whether the partial developmental block in Rag2c/c thymocytes15 is sufficient to produce genomic instability and lymphomagenesis, we crossed core Rag1 knock-in animals, which display diminished recombination and a strong block in B and T cell development14,24 (Supplementary Fig. 1), into a p53 deficient background. Rag1c/c p53−/− mice survived at an average age of 18.7 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 8a), barely distinguishable from p53−/− mice. Also like p53−/− mice, only two-thirds of Rag1c/c p53−/− mice developed thymic lymphomas (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Futhermore, metaphase DNA-FISH analyses on two Rag1c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas (8383T and 8411T) (Supplementary Fig. 9) and aCGH analysis on genomic DNA from four Rag1c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas (8315T, 8333T, 8383T, 8411T) (Supplementary Fig. 10) showed no evidence of recurrent translocations, genomic amplification or genomic deletion at chromosome 14 and chromosome 12. The genomic instability observed in Rag2c/c p53−/− thymic lymphomas is therefore associated specifically with loss of the RAG2 C-terminus, and does not result from the developmental block in core RAG2 homozygotes.

We next asked whether core RAG2 promotes genomic instability in the presence of p53 by using three-dimensional interphase DNA-FISH to examine the integrity of Tcrα/δ locus (Fig. 3c) in Rag2c/c double positive (DP) thymocytes. The two alleles appeared as two pairs of signals (Tcrα/δ V and Tcrα/δ C, mapping the two ends of the locus) in most (>98%) wild-type and p53−/− DP thymocytes (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating that p53 deficiency alone does not disrupt the integrity of the Tcrα/δ locus, as expected25. In contrast, Rag2c/c DP thymocytes displayed a three- to five-fold increase in the number of cells showing loss of at least one signal (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. 11). These results suggest that core RAG2 promotes genomic instability at the Tcrα/δ locus, a phenotype similar to that previously reported in Atm−/− and 53bp1−/− animals9,25.

We noted that both Rag2c/c p53−/− and Atm −/− mice feature RAG-dependent genomic instability at the Tcrα/δ and Igh loci, with development of pro-T cell lymphomas bearing clonal translocations, including 12/14 translocations2,3,7–11. To determine whether Atm−/− thymic lymphomas also harbor amplification close to the Tcrα/δ locus, we performed DNA-FISH analysis for Tcrα/δ and chromosome 14 on metaphases from one Atm−/− thymic lymphoma (10375T) (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Both chromosomes 14 showed translocations with breakpoints within the Tcrα/δ locus, and amplification of the Tcrα/δ V region on one allele (Supplementary Fig. 12a), results that were confirmed by array-CGH analysis (Supplementary Fig. 12b). We also observed loss of DNA at a distal region of chromosome 12, near the Igh locus (Supplementary Fig. 12b), as in Rag2c/c p53−/− lymphomas (Fig. 3 a,b; Supplementary Fig. 6). These data agree with recent analysis of thymic lymphomas from ATM-deficient mice7. Thymic lymphomas that arise in other mutant backgrounds such as p53, core RAG1/p53 (Supplementary Fig 8, 9, 10), Eβ/p53 or H2AX/p53 lack recurrent amplifications of chromosome 14 regions and/or recurrent chromosome 12/14 translocations, and thus appear to arise from distinct mechanisms.

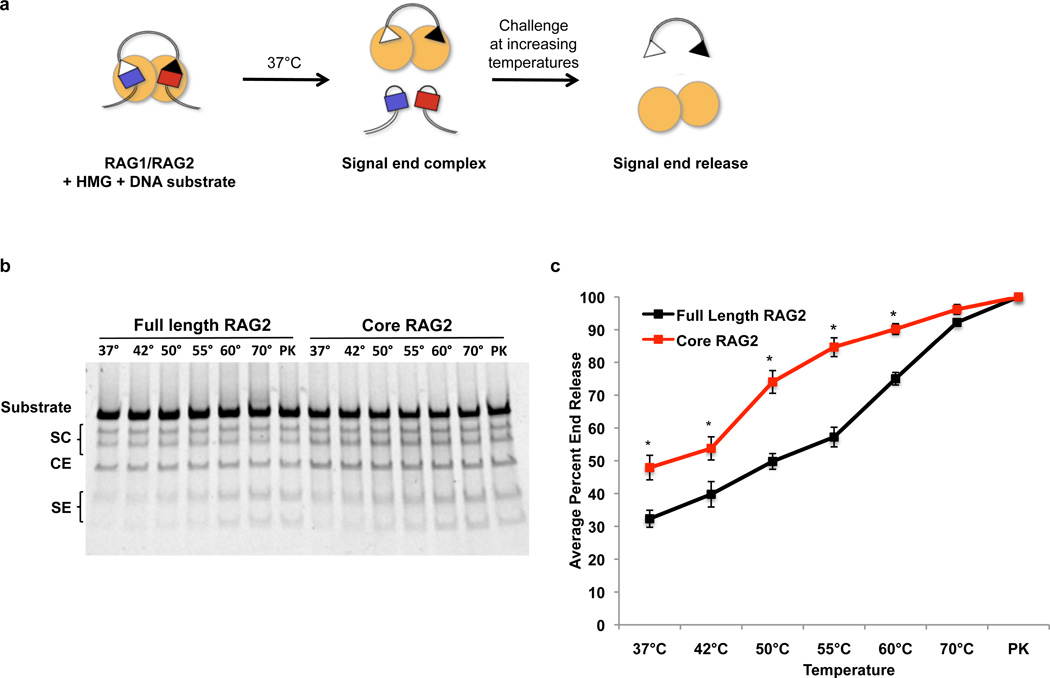

Our data reveal a novel in vivo function for the RAG2 C-terminus in promoting genomic stability. How does core RAG2 allow genomic instability? We hypothesized that core RAG2, like the absence of ATM3, destabilizes the post-cleavage complex. To investigate this, we generated RAG-signal end complexes by in vitro cleavage and challenged them at increasing temperatures, followed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4). Complexes containing full length RAG2 did not release 50% of signal ends until 55°C (Fig. 4b, c), as expected13,26. In contrast, core RAG2-containing complexes displayed statistically significant instability at lower temperatures, with 50% end release at 37°C (Fig. 4b, c). To examine the post-cleavage complex in vivo, we analyzed inversional recombination, which requires coordination of all four DNA ends. Decreased inversional recombination and increased formation of hybrid joints (generated by joining of a coding end to a signal end, in this case revealing defects in formation of four-ended inversion products) has been reported in ATM- and MRE11 complex-deficient cells3,27,28. As expected3,28, we observed increased hybrid joint formation at the Igκ locus (Vκ6-23 to Jκ1) in Atm−/− and NbsΔB/ΔB splenocytes (Supplementary Fig. 13). Importantly, we observed increased Vκ6-23-to-Jκ1 hybrid joints in Rag2c/c splenocytes, compared to their wild-type and Rag2c/+ counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 13). These results are supported by the observation that Rag2c/c lymphocytes exhibit defects in inversional recombination15. Together, these data support our hypothesis that core RAG2 impairs the stability of the RAG post-cleavage complex in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 4. The C-terminus of RAG2 stabilizes the RAG post-cleavage complex.

a. Biochemical end release assay. Purified GST-tagged core RAG1and non-tagged RAG2 (full length or core) proteins (yellow circles) cleave a 500bp DNA substrate at 37°C. Post-cleavage signal end complexes are thermally challenged at increasing temperatures to force the release of signal ends, which are detected after electrophoresis and gel staining. b. Representative gel for end release assays. Numbers above each lane indicate the temperatures the reactions were heated to before electrophoresis. PK, samples treated with proteinase K and SDS; SC, single cleavages; SE, signal ends; CE, coding ends. c. Quantification of SE release, measured as the combined amount of signal ends divided by the signal from the total amount of DNA in the lane, from six experiments using two different protein preparations (*P < 0.05, Student’s t-test).

Our data support a common model for genomic instability in Rag2c/c p53−/− and Atm−/− mice: premature release of RAG-generated DSBs from the RAG post-cleavage complex allows ends to escape the normal joining mechanisms, to persist, and to be potentially joined by alternative NHEJ, a pathway permissive for chromosome tranlocations and amplification4,29. Both end release and end persistence are promoted by ATM deficiency2,3, likely because ATM both stabilizes the RAG post-cleavage complex3 and activates p53-dependent checkpoints/apoptosis. In Rag2c/c p53−/− mice, end persistence might be augmented by ongoing RAG activity through the cell cycle resulting from impaired degradation of core RAG2, which lacks the cell-cycle regulated degradation motif18,30.

The complete penetrance, rapid development of lymphoma, and extraordinary degree of RAG-mediated genomic instability make Rag2c/c p53−/− mice an attractive model for investigating the spectrum of somatic genome rearrangements underlying lymphomagenesis.

Methods Summary

Mice

Mice were bred in the NYU SPF facility; animal care was approved by the NYU SoM Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol # 090308-2).

Analysis of tumor cells

Lymphoid tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry with antibodies against surface B- and T- cell markers. Metaphases were prepared and analyzed as described in Full Methods.

FISH and image analysis

DNA FISH was performed using BAC probes as described in Full Methods. Interphase FISH was performed on double positive thymocytes isolated by cell sorting according to protocols described in Full Methods. Images were obtained by confocal microscopy on a Leica SP5 AOBS system (Acousto-Optical Beam Splitter), with optical sections separated by 0.3 micrometers. Images were analyzed using Image J software. Metaphase spreads were imaged by fluorescent microscopy on a Zeiss Imager Z2 Metasystems METAFER 3.8 system and analyzed using ISIS software. Statistical analysis of image parameters was performed using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Biochemical end release assay

The stability of RAG-signal end complexes was measured as described in Full Methods. Briefly, RAG cleavage reactions were aliquoted into microfuge tubes and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 30 minutes, followed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. DNA was stained using SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen) and quantified with Quantity One software (Biorad). Student's T-test assuming equal variance was used to calculate statistical significance.

aCGH analysis

For CGH, genomic DNA from mouse thymic lymphomas was profiled against matched thymic DNA from wild type mice. aCGH experiments were performed on two color Agilent 244A Mouse Genome Microarrays. Data analysis was performed as described in Full Methods.

Full Methods

Mice

We obtained wild type (Taconic), Rag2c/c15, Rag1c/c 24, p53−/− (The Jackson Laboratory20) and Atm−/− (The Jackson Laboratory11) mice for this study. Rag2c/c or Rag1c/c mice were bred with p53-deficient mice to generate doubly deficient mice. Genotyping of these mutants was performed by PCR of tail DNA as described in the relevant references11,15,20,24.

Characterization of tumor cells and metaphase preparation

Lymphoid tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry with antibodies against surface B-cell (CD43, B220, IgM) and T-cell (CD4, CD8, CD3, TCRβ) markers. FACS analysis employed a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with FacsDiVa and FlowJo. For metaphase preparation, tumor cells were prepared as previously described31,32. Briefly, primary tumor cells were grown in complete RPMI media for 4 hours and exposed to Colcemid (0.04 µg/ml, GIBCO, Karyo max Colcemid solution) for two hours at 37°C. Then, cells were incubated in KCl 75mM for 15 minutes at 37°C, fixed in fixative solution (75% methanol/25% acetic acid) and washed three times in the fixative. Cell suspension was dropped onto pre-chilled glass slides and air-dried for further analysis.

G-banding and Spectral Karyotyping

Optimally aged slides were treated for the induction of G-banding following the routine procedure33. Spectral karyotyping was performed using the mouse chromosome SKY probe Applied Spectral Imaging (ASI, Vista, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to determine chromosomal rearrangements in the tumor samples. The slides were analyzed using Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. G-banding as well as SKY images were captured and karyotyped using ASI system.

DNA FISH probes

BAC probes for the Igh and Tcrα/δ loci were labeled by nick-translation and prepared as previously described34,35. For the Igh locus, BAC 199 (Igh C) and BAC RP24-386J17 (Igh V) were labeled in Alexa Fluor 594 and 488 respectively (Molecular probes). For the Tcrα/δ locus, BAC RP23-304L21 (Tcrα/δ V) and RP-23 255N13 (Tcrα/δ C) were labeled in Alexa Fluor 488 or 594. StarFISH-concentrated mouse FITC or Cy3 chromosome 12 or 14 paints were prepared following supplier’s instructions (Cambio). BAC probes were resuspended in hybridization buffer (10% dextran sulfate, 5X Denharts solution, 50% formamide) or in paint hyb buffer, denatured for 5 min at 95°C and pre-annealed for 45 min at 37°C before hybridization on cells.

DNA FISH on metaphase spreads

Slides were dehydrated in ethanol series, denatured in 70% formamide/2x SSC (pH 7–7.4) for 1 min 30s at 75°C, dehydrated again in cold ethanol series, and hybridized with probes o/n at 37°C in a humid chamber. Slides were then washed twice in 50% formamide/2x SSC and twice in 2x SSC for 5 min at 37°C each. Finally, cells were mounted in ProLong Gold (Invitrogen) containing DAPI to counterstain total DNA.

DNA FISH on interphase nuclei

Double-positive thymocytes were isolated from total thymi on a Beckman-Coulter MoFlo cell sorter as Thy1.2+CD4+CD8+ cells using the following antibodies: PE-Cy7-coupled anti-CD90.2 (Thy1.2; 53-2.1), APC-coupled anti-CD4 (L3T4) and FITC-coupled anti-CD8 (53-6.7). Cells were washed two times in 1X PBS and dropped onto poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips. For 3-dimensional DNA-FISH analyses we used a protocol for immunofluorescence / DNA-FISH previously described34,35, with protein detection step omitted. Briefly, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde / 1X PBS for 10 min at RT, permeabilized in 0.4% Triton / 1X PBS for 5 min on ice, incubated with 0.01 mg/ml Rnase A for one hour at 37°C and permeabilized again in 0.7% Triton / 0.1M HCl for 10 min on ice. Cells were then denatured in 1.9M HCl for 30 minutes at RT, rinsed in cold 1X PBS and hybridized overnight with probes at 37°C in a humid chamber. Cells were then rinsed in 2X SSC at 37°C, 2X SCC at RT and 1X SSC at RT, 30 min each. Finally, cells were mounted in ProLong Gold (Invitrogen) containing DAPI to counterstain total DNA.

Biochemical end release assay

End release assay to measure the stability of the signal-end complexes was performed as previously described26. For RAG-mediated cleavage, 100ng of recombination substrate (PCR product from pJH289) was incubated for 3 hours at 37°C with 200ng purified RAG protein and 200ng of purified recombinant HMGB1 in a buffer containing 50mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 25mM KCl, 4mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 0.1mg BSA, 5mM CaCl2 and 5mM MgCl2. Reactions were then aliquoted into microfuge tubes and incubated at different temperatures, or treated with stop buffer [10mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS, 0.35mg/ml proteinase K (Sigma Aldrich)] for 30 minutes and then ran out on 4–20% acrylamide TBE gels (Invitrogen).

aCGH analysis

aCGH experiments were performed on two color Agilent 244A Mouse Genome Microarray. After internal Agilent quality control, the collected data was background substracted and normalized using Loess Method36. We used circular binary segmentation method to define regions of copy number alteration versus the control37 and applied cghMCR method for extraction of altered minimum common regions between the samples38. The analyses and visualizations were performed using R statistical program [R development Core Team, 2009].

Supplementary Material

Acknowlegments

We thank Mark Schlissel for the generous gift of core Rag2 mice, Fred Alt for the generous gift of core Rag1 mice and Susannah Hewitt for the Igh BAC probes. D.B.R. was supported by NIH Roadmap Initiative in Nanomedicine through a Nanomedicine Development Center award (1PN2EY018244), NIH grant CA104588, and the Irene Diamond Fund. L.D. is a Fellow of The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. A.V.A. was supported in part by grant 1UL1RR029893 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. J.A.S. was supported by an R01GM086852, a NIH Challenge grant NCI R01CA145746-01 and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Contributions

L.D. and D.B.R. conceived the study and co-wrote the manuscript. L.D. designed the experiments. L.D., J.C. M.C. and A.M. performed the experiments. Y.C. provided assistance with the mouse colonies. A.V.A. performed the aCGH data analysis. J.A.S. and S.C. provided technical and conceptual support. J.C. and J.A.S revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kuppers R, Dalla-Favera R. Mechanisms of chromosomal translocations in B cell lymphomas. Oncogene. 2001;20:5580–5594. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callen E, et al. ATM prevents the persistence and propagation of chromosome breaks in lymphocytes. Cell. 2007;130:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredemeyer AL, et al. ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2006;442:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature04866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu C, et al. Unrepaired DNA breaks in p53-deficient cells lead to oncogenic gene amplification subsequent to translocations. Cell. 2002;109:811–821. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y, et al. Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genomic stability and development. Nature. 2000;404:897–900. doi: 10.1038/35009138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Difilippantonio MJ, et al. DNA repair protein Ku80 suppresses chromosomal aberrations and malignant transformation. Nature. 2000;404:510–514. doi: 10.1038/35006670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zha S, et al. ATM-deficient thymic lymphoma is associated with aberrant tcrd rearrangement and gene amplification. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1369–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callen E, et al. Chimeric IgH-TCRalpha/delta translocations in T lymphocytes mediated by RAG. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2408–2412. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matei IR, et al. ATM deficiency disrupts Tcra locus integrity and the maturation of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. Blood. 2007;109:1887–1896. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liyanage M, et al. Abnormal rearrangement within the alpha/delta T-cell receptor locus in lymphomas from Atm-deficient mice. Blood. 2000;96:1940–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow C, et al. Atm-deficient mice: A paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1996;86:159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corneo B, et al. Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature. 2007;449:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature06168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee GS, Neiditch MB, Salus SS, Roth DB. RAG proteins shepherd double-strand breaks to a specific pathway, suppressing error-prone repair, but RAG nicking initiates homologous recombination. Cell. 2004;117:171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JM, Simkus C. The roles of the RAG1 and RAG2 "non-core" regions in V(D)J recombination and lymphocyte development. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2009;57:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang HE, et al. The "dispensable" portion of RAG2 is necessary for efficient V-to-DJ rearrangement during B and T cell development. Immunity. 2002;17:639–651. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu JX, Kale SB, Yarnell Schultz H, Roth DB. Separation-of-function mutants reveal critical roles for RAG2 in both the cleavage and joining steps of V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell. 2001;7:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steen SB, Han J-O, Mundy C, Oettinger MA, Roth DB. Roles of the "dispensable" portions of RAG-1 and RAG-2 in V(D)J recombination. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19:3010–3017. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curry JD, Schlissel MS. RAG2's non-core domain contributes to the ordered regulation of V(D)J recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5750–5762. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talukder SR, Dudley DD, Alt FW, Takahama Y, Akamatsu Y. Increased frequency of aberrant V(D)J recombination products in core RAG-expressing mice. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004;32:4539–4549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacks T, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao MJ, et al. No requirement for V(D)J recombination in p53-deficient thymic lymphoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3495–3501. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forster A, Hobart M, Hengartner H, Rabbitts TH. An immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene is altered in two T-cell clones. Nature. 1980;286:897–899. doi: 10.1038/286897a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haines BB, et al. Block of T cell development in P53-deficient mice accelerates development of lymphomas with characteristic RAG-dependent cytogenetic alterations. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley DD, et al. Impaired V(D)J recombination and lymphocyte development in core RAG1-expressing mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1439–1450. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Difilippantonio S, et al. 53BP1 facilitates long-range DNA end-joining during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2008;456:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnal SM, Holub AJ, Salus SS, Roth DB. Non-consensus heptamer sequences destabilize the RAG post-cleavage complex, making ends available to alternative DNA repair pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2944–2954. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helmink BA, et al. MRN complex function in the repair of chromosomal Rag-mediated DNA double-strand breaks. J Exp Med. 2009 doi: 10.1084/jem.20081326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deriano L, Stracker TH, Baker A, Petrini JH, Roth DB. Roles for NBS1 in alternative nonhomologous end-joining of V(D)J recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 2009;34:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simsek D, Jasin M. Alternative end-joining is suppressed by the canonical NHEJ component Xrcc4-ligase IV during chromosomal translocation formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, Dordai DI, Lee J, Desiderio S. A conserved degradation signal regulates RAG-2 accumulation during cell division and links V(D)J recombination to the cell cycle. Immunity. 1996;5:575–589. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theunissen JW, Petrini JH. Methods for studying the cellular response to DNA damage: influence of the Mre11 complex on chromosome metabolism. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:251–284. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Multani AS, et al. Caspase-dependent apoptosis induced by telomere cleavage and TRF2 loss. Neoplasia. 2000;2:339–345. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pathak S. Chromosome banding techniques. J Reprod Med. 1976;17:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewitt SL, et al. RAG-1 and ATM coordinate monoallelic recombination and nuclear positioning of immunoglobulin loci. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:655–664. doi: 10.1038/ni.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skok JA, et al. Reversible contraction by looping of the Tcra and Tcrb loci in rearranging thymocytes. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ni1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang YH, et al. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aguirre AJ, et al. High-resolution characterization of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9067–9072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402932101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.