Abstract

We examined whether exiting high school was associated with changes in the mother–child relationship. Participants were 170 mothers of youth with ASD who were part of our larger longitudinal study and who exited high school during the study; data were collected four times over 7 years. Results indicated improvement in the mother–child relationship while in high school; however, improvement in all indices slowed or stopped after exit. Mothers of youth with ASD without an intellectual disability (ID) and who had more unmet service needs evidenced the least improvement after exit. Our findings provide further evidence that the years after high school exit are a time of increased risk, especially for those with ASD without ID and whose families are under-resourced.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Transition to adulthood, Mother–child relationship, Burden, Warmth

Introduction

The transition out of high school and into adult life for individuals with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a time of substantial change. At high school exit he or she loses the entitlement to many (and sometimes all) of the services received while in the school system. In most cases, he or she enters a world of adult services plagued by waiting lists and a dearth of appropriate opportunities to achieve a maximum level of adult independence (Howlin et al. 2005). After exiting high school, parents (particularly mothers) continue in their role as the main source of support and care for adults with ASD, and often must take on increased responsibility for service coordination from the school system. This role does not end when the son or daughter moves away from the parental home (Krauss et al. 2005); indeed, parental responsibility and involvement generally last to some degree for the rest of the parent's life (Seltzer et al. 2001). Given the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, the centrality of the family in the life of a person with ASD, and the reliance of the service system on the family as the primary source of support, there is an urgent public health and scientific need to understand the range of factors that influence the well-being of families and the mother–child relationship during the “transition years” and beyond.

The present study extends our previous research examining the impact of high school exit on the autism behavioral phenotype (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a) by focusing on the ways in which this transition may also alter aspects of the mother–child relationship. Furthermore, we tested whether the impact of high school exit depended on four factors that have been found to be either important correlates of the mother–child relationship or moderators of the impact of high school exit on the autism behavioral phenotype: a comorbid intellectual disability (ID), gender, the extent of unmet disability service needs of the youth with ASD, and family income. Currently, there is no empirical evidence regarding the extent and nature of the changes that occur in the mother–child relationship from before to after this transition for families of youth with ASD. Identifying characteristics of mothers and families who adapt well during the transition years will provide important knowledge that can be used to develop interventions and inform services and policy.

The Mother–Child Relationship During the Transition to Adulthood

For typically developing adolescents, the transition to adulthood involves leaving the parental home and living independently, finishing school, starting a job, and marrying and having children (Fussell and Furstenberg 2005). Only one of these tasks—finishing school—is accomplished by most individuals with ASD; thus, we chose high school exit as a key indicator of the transition to adulthood.

The transition to adulthood is a time of great stress for families of youth with ASD. Mothers report a tremendous amount of anxiety and trepidation prior to their son or daughter's high school exit (Fong et al. 1993). Mothers of non-disabled adolescents often find the transition to adulthood to be difficult (Kidwell et al. 1983; Montemayor et al. 1993); families of individuals with ASD must contend with these normative challenges, while at the same time assuming the role of service coordinator for their son or daughter after he or she leaves school (Howlin 2005). The situation becomes potentially more serious when considering that all of this change is occurring among families that tend to experience more stress throughout the life course than families of children with any other developmental disorder (Abbeduto et al. 2004; Bouma and Schweitzer 1990; Donovan 1988; Dumas et al. 1991; Holroyd and McArthur 1976; Rodrigue et al. 1990; Wolf et al. 1989).

Not only are high levels of burden and stress among mothers reasons for clinical concern in and of themselves, but also because they are related to more critical and less warm mother–child relationships among families of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Hastings et al. 2006; Lam et al. 2003; Orsmond et al. 2006). Thus, if the transition to adulthood is a time of great worry and stress among mothers of children with ASD, the mother–child relationship may become less positive during the transition years. Poor mother–child relationships place youth with ASD at risk for higher levels of maladaptive behaviors (Greenberg et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008) but the mother–child relationship is malleable (Butzlaff and Hooley 1998), presenting a possible avenue for interventions.

Our recent research generally suggests that the mother–child relationship may be at risk during the transition to adulthood due to behavioral and symptom changes in the son or daughter with ASD co-occurring with this transition. Using longitudinal data collected over a 10-year period from a larger ongoing longitudinal study of mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (for a description of the larger study see Seltzer et al. in press), Taylor and Seltzer (2010a) examined how exiting high school impacted the autism behavioral phenotype for youth with ASD who exited during the study period. We found that the improvement in the autism behavioral phenotype (i.e., reduction in autism symptoms and behavior problems) that was observed while youth were in high school slowed down and, in some cases, reversed after high school exit. Because of the strong relations shown in past research between maladaptive behaviors and autism symptoms in youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities (including ASD) and the quality of the mother–child relationship (Beck et al. 2004; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006; Lam et al. 2003; Orsmond et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008), the slowing of improvement in the behavioral phenotype after high school exit may be associated with greater strain in the mother–child relationship at this time.

However, we have also found patterns of improvement in the mother–child relationship over time. Lounds et al. (2007) found that mothers of youth with ASD who had previously exited high school reported greater improvement in mother–child positive affect over time, relative to mothers whose son or daughter was still in high school (and thus younger at the start of the study). However, this analysis did not examine change in the mother–child relationship from before and to after high school exit, and it is difficult to know whether the greater positive change for mothers of youth who had recently exited is due to cohort effects or true intra-individual change.

Regardless of possible explanations, more research is needed that directly examines the impact of high school exit on indices of the mother–child relationship. The present study examines the impact of high school exit by estimating the rate of change in mother–child positive affect, subjective burden, and maternal warmth over a seven-year period, and further whether the rate of those changes differs after high school exit.

Correlates of Changes in the Mother–Child Relationship After High School Exit

Individuals with ASD and their families are a heterogeneous group, and the ways that they experience the exit of the son or daughter out of the school system and into adult life will differ by characteristics of the family. To investigate this heterogeneity, the present study examined four possible correlates of change suggested by the extant research: whether or not the youth with ASD had a comorbid ID, his or her gender, family income, and the number of unmet disability service needs.

There is some research to suggest that individuals with ASD without comorbid ID might be at risk for problems in the mother–child relationship during the transition to adulthood. In our studies (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a, b), youth with ASD without ID had more pronounced slowing in behavioral phenotypic improvement after high school exit, and were more likely to have insufficient or no daytime activities during the years after exit relative to youth with ASD and comorbid ID. Furthermore, Dossetor et al. (1994) found higher rates of criticism among parents of adolescents who had less severe ID compared to more severe, and interpreted these findings in light of parental attributions about the behaviors of their son or daughter. It is a well-established finding that caregivers who attribute a family member's problematic behaviors as controllable by that individual have higher levels of criticism and lower levels of warmth, relative to caregivers who attribute the behaviors to uncontrollable causes (Barrowclough and Hooley 2003; Tarrier et al. 2002; Weisman et al. 1993). Dossetor et al. (1994) suggested that parents of individuals with less severe ID are more likely to believe that difficult behaviors are under the voluntary control of the son or daughter relative to parents of individuals with more severe ID, leading to more critical parent–child relationships.

Although studies have yet to examine the role of individual functioning on maternal attributions about behavior in an ASD sample, it is reasonable to expect that mothers of youth with ASD without ID (who have higher levels of functioning on average) may be more likely to attribute their son or daughter's maladaptive behaviors as under his or her own control compared to mothers of youth with ASD with ID (who have lower levels of functioning). The stress of less phenotypic improvement and inadequate adult employment after exit, coupled with a greater likelihood that their mother will make attributions of internal control about maladaptive behaviors, suggests that youth with ASD who do not have ID may be at risk for poorer mother–child relationships during the transition years relative to those with ID.

Relations between the gender of the son or daughter with ASD and indices of the mother–child relationship vary across studies. Among typically developing parent– child dyads, mothers and their young adult daughters tend to be closer than mothers and their similarly-aged sons (Rossi and Rossi 1990; Ryff and Seltzer 1996). Alternatively, research on the mother–child relationship with mothers of sons or daughters with intellectual and developmental disabilities (including ASD) tend not to find differences based on the gender of the individual with the disability (Beck et al. 2004; Greenberg et al. 2006; Orsmond et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008). One exception to this pattern is the study by Lounds et al. (2007), which found that mothers of daughters had relationships that were improving more over time relative to mothers of sons. Because the Lounds et al. (2007) study focused on the same age range of youth with ASD as in the present analyses (under age 22 at the start of the study), whereas previous studies included a broader age range, and because the Lounds study included a partially overlapping sample as the present analysis, we hypothesized that mothers of daughters would experience better mother–child relationships over time compared to mothers of sons at this life stage.

Family socio-economic resources may influence how aspects of the mother–child relationship change during the transition out of high school. Although socio-economic status is understudied in ASD populations, there is some research that suggests that families who have greater socio-economic resources are able to obtain an ASD diagnosis earlier (Mandell et al. 2005) and have better access to services for their school-aged children with ASD (Liptak et al. 2008; Thomas et al. 2007). Furthermore, Taylor and Seltzer (2010a) found that autism symptoms ceased to improve after high school exit for youth with ASD from lower income families, while improvement continued for those from higher income families. In that study, income impacted change in autism symptoms only after high school exit, but not while youth with ASD were in high school. This pattern may reflect income-based disparities in services that intensify after youth with ASD leave high school and enter the adult service system. It is likely that these disparities and less phenotypic improvement for youth with ASD from lower income families result in greater parental stress for these families after exit, reflected in more problems in the parent–child relationship after high school exit relative to families with higher incomes.

Finally, the number of services that the son or daughter with ASD needs but is not receiving (unmet service needs) while in the secondary school system may impact how the mother–child relationship changes after exit. Smith (1997) found that more unmet disability service needs were related to higher levels of subjective burden among mothers of adults with ID. Youth with ASD are likely to receive more services and have fewer unmet needs while in school and covered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, relative to after high school exit when they lose entitlement to services. Those who already have high levels of unmet service needs while in school may be at particular risk after they leave the protective umbrella of the school system, with more burden falling on the mothers. Thus, we expect that mothers of youth with ASD who have high levels of unmet service needs while in the secondary school system will experience less positive change in the mother–child relationship after high school exit.

The Present Study

The present study is a follow-up to our research on the impact of high school exit on changes in the behavioral phenotype of adolescents and young adults with ASD (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a). As the first empirical study focused on changes in the functioning of families who have a son or daughter with ASD from before high school exit to after, this research will help us to understand the characteristics of families that are able to more successfully negotiate this transition, which may have implications for intervention.

Therefore, our first aim was to determine whether exiting the secondary school system was associated with changes in aspects of the mother–child relationship for adolescents and young adults with ASD. Based on our previous research finding that improvements in the autism behavioral phenotype slow significantly after high school exit (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a), we hypothesized that the transition out of high school would similarly be followed by negative changes in the mother–child relationship, as measured by positive affect in the mother–child relationship, subjective burden, and maternal warmth.

Our second aim was to examine whether changes in aspects of the mother–child relationship, both prior to high school exit and after exit, depended on the ID status or gender of the adolescents and young adults with ASD, family income, or unmet service needs. We expected less improvement in the mother–child relationship for mothers of males, mothers of those without ID who had more unmet service needs, as well as mothers with lower family incomes.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The present analysis used a subsample (n = 170) drawn from our larger longitudinal study of families of adolescents and adults with ASD (N = 406; Seltzer et al. 2003; Seltzer et al. in press). The criteria for inclusion in the larger study were that the son or daughter with ASD was age 10 or older (age range = 10–52 at the beginning of the study), had received an ASD diagnosis (autistic disorder, Asperger disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified) from an educational or health professional, and had a researcher-administered Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994) profile consistent with the diagnosis. Nearly all of the sample members (94.6%) met the ADI-R lifetime criteria for a diagnosis of autistic disorder. Case-by-case review of the other sample members (5.4%) determined that their ADI-R profile was consistent with their ASD diagnosis (i.e., meeting the cutoffs for reciprocal social interaction and repetitive behaviors for Asperger disorder, and for reciprocal social interaction and either impaired communication or repetitive behaviors for PDD-NOS). Half of the participants lived in Wisconsin (n = 202) and half in Massachusetts (n = 204). We used identical recruitment and data-collection methods at both sites. Families received information about the study through service agencies, schools, and clinics; those who were interested contacted a study coordinator and were subsequently enrolled. Five waves of data have thus far been collected and are available for analysis: four waves collected every 18 months from 1998 to 2003, spanning a 4.5 year period, and a fifth wave collected in 2008, 10 years after the study began. At each time point, data were collected from the primary caregiver, who was usually the mother, via in-home interviews that typically lasted 2–3 h and via self-administered questionnaires.

The present analyses make use of four waves of data (referred to as Time 2 through Time 5), which are the time points when all of the mother–child relationship variables of interest were collected. We included families whose son or daughter with ASD was in the secondary school system at Time 2 and who exited high school between any of these four data points or who remained in high school at the last point of data collection. By focusing on this sample, it was possible to examine change in the mother–child relationship during the transition to adulthood, an understudied period in the lives of individuals with ASD and their families. Of a possible 178 sample members who met the above inclusion criterion, there were 8 who were dropped from the present analysis. In 6 cases, the father was the respondent instead of the mother. For one remaining family, the mother completed separate interviews for three children with ASD; we randomly chose one child as the target child, resulting in the elimination of two cases. This resulted in a final sample of 170 mother–child dyads.

The adolescents and young adults with ASD included in this analysis averaged 16.7 years of age (SD = 2.3) at the first time point for these analyses (Time 2), with a range from 11.3 to 21.9 years. (Thus, when we refer to them as “children” it is in the sense that they are the sons and daughters of their mothers, not that they are young in age). Three-fourths (75.9%) were male, 82.4% were living with their parents at this time, and three-fourths (75.3%) were verbal, as indicated by daily functional use of at least three-word phrases. Nearly two-thirds (63.5%) had comorbid ID. Thus, the characteristics of the present sample are consistent with what would be expected based on epidemiological studies of autistic disorder (Bryson and Smith 1998; Fombonne 2003).

At Time 2, the mothers in this subsample ranged from 33.9 years to 67.4 years of age (M = 46.4, SD = 5.3). Over half (60.6%) had attained at least a bachelor's degree. Mothers were primarily married at Time 1 (82.0%) and 91.9% were Caucasian. The median household income was between $60,000 and $70,000.

All of the 170 sample members provided Time 2 data. Data were available for 154 families (90.6%) at Time 3, 138 (81.2%) at Time 4, and 114 (67.1%) at Time 5. Mothers who remained in the study at Time 5 (n = 114) were compared on all of the study variables as well as indicators of socioeconomic status to those who dropped out of the study or those who died (or whose child died) prior to the most recent wave of measurement (n = 56). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in child's gender, rates of comorbid ID, residential status, age, or maladaptive behaviors, nor were there differences in maternal age, marital status, years of education, race/ethnicity, or family income. In terms of the study variables, similar levels of the dependent variables at Time 2 (mother–child positive affect, subjective burden, and warmth) were reported for mothers who remained in the study at Time 5, compared to those who did not continue to participate (data available from the first author). These overall patterns suggest similarity on a great number of dimensions between mothers who had complete data compared to those who had partial data analyzed for the present study.

Measures

Outcome Variables: Aspects of the Mother–Child Relationship

Mother–child Positive Affect

Positive affect in the mother–child relationship was assessed using the Positive Affect Index (Bengtson and Schrader 1982). Five self-report items that reflected the mother's feelings toward her son or daughter (e.g. “How much affection do you have toward your son/daughter?”) were used from this scale. Items rated understanding, trust, fairness, respect, and affection in the relationship on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = not much, 3 = some, 4 = pretty much, 5 = very much, 6 = extremely). Previous researchers have established the construct and discriminant validity of the Positive Affect Index (Bengtson and Allen 1993; Bengtson and Schrader 1982; Greenberg et al. 2004). This index has been found to be a reliable measure of maternal positive affect toward adolescent and adult children with autism (Orsmond et al. 2006). Possible scores range from 5 to 30, with higher scores indicative of greater positive affect in the mother–child relationship.

Burden

The subjective burden reported by the mother emanating from providing care to the son or daughter with ASD was measured by the Zarit Burden Inventory (Zarit et al. 1980). This measure was originally used in research on caregivers of frail elderly persons (Stephens and Kinney 1989), but has since been used in numerous studies of family caregiving to assess the caregiver's perception about or appraisal of the burdens associated with the caregiving role (e.g., time demands, financial strains, lack of privacy). Each of the 30 items is answered using a 3-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 2 (extremely true). Examples include items such as, “Because of my involvement with my son/daughter, I don't have enough time for myself” and “I feel that my health has suffered because of my involvement with my son/daughter.” Alpha reliability for mothers of adults with ASD in this sample was .87. Possible scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more subjective burden.

Warmth

Ratings of warmth were coded from the Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS). Mothers were asked to speak about their son or daughter for 5 min without interruption and the speech sample was tape-recorded and transcribed for rating. Thus, the warmth ratings are not direct self-reports, but instead are measures of the emotional valence of the mother–child relationship extracted from a more general speech sample, and independently coded. The FMSS has been used to obtain valid and reliable ratings of expressed emotion (EE) in a variety of diagnostic groups (Moore and Kuipers 1999; Van Humbeeck et al. 2002,) including families of individuals with developmental disabilities (Beck et al. 2004; Hastings et al. 2006) and autism (Greenberg et al. 2006). We used the guidelines from the Camberwell Family Interview (Vaughn and Leff 1976) to generate individual ratings of warmth. Warmth ratings were based on (a) tone of voice; (b) spontaneity of expression of sympathy, concern, and empathy; and (c) expression of interest in the individual with ASD. Level of warmth was rated on a 6-point scale from 0 (no warmth) to 5 (high warmth; see Caspi et al. 2004, for a detailed description of warmth benchmarks). Ratings for this study were performed by a rater with over 20 years of experience coding the FMSS for all aspects of EE. A second rater independently coded 15 taped speech samples. The two raters had an interrater reliability of .79 for ratings of warmth. Neither rater was associated with our study, and both were blind to the measures of positive affect and burden. In our past research, we have found this measure of warmth to be associated with the maladaptive behaviors of adolescents and adults with ASD (Smith et al. 2008).

It is important to note that the ratings of warmth taken from the FMSS are measures of maternal verbal behavior about the child and are not observed measures of behavior directed at the child. Past research, however, has shown that this measure is a strong predictor of child outcomes (Butzlaff and Hooley 1998; Greenberg et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008). Additionally, researchers have found a significant relationship between observed family behavior and EE ratings (Hahlweg et al. 1989; McCarty et al. 2004; Woo et al. 2004).

Time-varying, Within-Persons Independent Variables

Time Since High School Exit

Detailed record review allowed for the determination of whether the son or daughter with ASD was enrolled in high school at each of the measurement times, as well as the date at which he or she left the school system. From this information, we calculated a variable indicating the amount of time that had passed since the person with ASD had exited high school at each data collection time point (coded as 0 when the son or daughter was still in high school). Some adolescents and young adults with ASD graduated with their peers but continued to receive services through the school system, while others never graduated but instead “timed out” of secondary school on their 22nd birthday. For clarity, the date of high school exit was defined as the month and year that the son or daughter stopped receiving services through the secondary school system (regardless of graduation date). Therefore, our high school exit variable is synonymous with exiting from school services.

Maladaptive Behaviors

Mothers completed the Behavior Problems subscale of the Scales of Independent Behaviors—Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks et al. 1996) at each of the four times of measurement. This subscale measures maladaptive behaviors, grouped in three domains (Bruininks et al. 1996): internalized behaviors (hurtful to self, unusual or repetitive habits, withdrawal or inattentive behavior), externalized behaviors (hurtful to others, destructive to property, disruptive behavior), and asocial behaviors (socially offensive behavior, uncooperative behavior). Mothers who indicated that their child displayed a given behavior then rated the frequency (1 = less than once a month to 5 = 1 or more times/hour) and the severity (1 = not serious to 5 = extremely serious) of the behavior. Standardized algorithms (Bruininks et al. 1996) translate the frequency and severity ratings into an overall maladaptive behaviors score. Higher scores indicate more severe maladaptive behaviors. Reliability and validity of this measure have been established by Bruininks et al. (1996).

Residential Status

At each time of measurement, mothers indicated where their adolescent or adult child lived. When the son or daughter lived at home, a code of 0 (co-residing) was assigned. When the child lived away from the family home (e.g., group home, independent living, etc.) a code of 1 (living away from the family home) was assigned.

Between-Persons Independent Variables

Intellectual Disability

Comorbid intellectual disability status (0 = no intellectual disability, 1 = intellectual disability) was determined using a variety of sources. Standardized IQ was obtained by administering the Wide Range Intelligence Test (WRIT; Glutting et al. 2000). The WRIT is a brief measure with strong psychometric properties and both verbal and nonverbal sections. Adaptive behavior was assessed by administering the Vineland Screener (Sparrow et al. 1993) to mothers. The 45-item screener measured daily living skills in the youth with ASD and correlates well with the full-scale Vineland score (r = .87 to .98). It has high interrater reliability (r = .98) and good external validity (Sparrow et al. 1993). Individuals with standard scores of 70 or below on both IQ and adaptive behavior measures were classified as having an intellectual disability (ID), consistent with diagnostic guidelines (Luckasson et al. 2002). For cases where the individual with ASD scored above 70 on either measure, or for whom either of the measures was missing, a review of medical and psychological records by three psychologists, combined with a clinical consensus procedure, was used to determine ID status.

Gender and Family Income

At the start of the study, the gender (0 = son, 1 = daughter) of the child with ASD was recorded. Mothers were also asked about their family's income in the previous year, coded from 1 = less than $5,000 to 13 = over $70,000.

Unmet Service Needs

At Time 2, when their sons and daughters with ASD were still in school, mothers reported on the following twelve services available to the son or daughter at the time of data collection: physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, psychological or psychiatric services, crisis/intervention services, personal care assistance, agency sponsored recreational or social activities, transportation services, income support, vocational services, respite services, and Medicaid. Mothers rated whether each service was received, and if not, whether that service was needed. The sum of services needed but not received was calculated as our measure of unmet service needs (possible range from 0 to 12). The mean number of unmet service needs for this sample was 2.14 (SD = 2.07).

Data Analysis

Multilevel modeling, using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling program (HLM; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002), was the primary method of data analysis used to examine changes in aspects of the mother–child relationship. Multilevel modeling has several advantages over more traditional ways to study change; one advantage that is especially salient for longitudinal research is its ability to flexibly handle missing data. As long as one occasion of measurement is available, the case can be used in the estimation of effects. However, individuals who have more data points yield more reliable estimates, which are weighted more heavily in the group mean estimates than individuals who have fewer time points (Bryk and Raudenbush 1987; Francis et al. 1991). The use of all available time points for participants reduces bias (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Singer and Willett 2003). Furthermore, multilevel modeling allows for the measurement periods to be unequally spaced. This flexibility is especially beneficial when examining the amount of time that has passed since the son or daughter with ASD exited secondary school; in some cases the person with autism exited within a month prior to the measurement occasion, whereas in other cases he or she exited a year or more before the subsequent time point of measurement. Multilevel modeling allows us to accurately represent the individual variability in the amount of time that has passed since high school exit (as well as individual variability in timing of measurement occasions).

In order to address the first research aim, examining the average effect of high school exit on changes in the mother–child relationship, a set of “unconditional” models were estimated that included only the two main Level 1 (within-persons) time variables: the amount of time that had passed since the start of the study; and the amount of time that had passed since high school exit. Three separate models were run, one for each aspect of the mother–child relationship (mother–child positive affect, maternal subjective burden, and maternal warmth), resulting in an initial score for each variable, a slope reflecting rate of change prior to high school exit, and a slope reflecting the difference in rate of change after high school exit (Singer and Willett 2003). After determining slopes, these models were re-estimated controlling for maladaptive behaviors and residential status at each time point as time-varying covariates. Controlling for these variables allowed us to determine whether differences in the trajectory of mother–child relationship variables after high school exit could be accounted for by changes in maladaptive behaviors or residential status (i.e., adolescents and young adults with ASD moving out of the parental home) at this time.

The second research aim addressed whether changes in aspects of the mother–child relationship, either prior to or after high school exit, depended on the ID status or gender of the adolescents and young adults with ASD, as well as family income and unmet service needs. In a second set of models, those between-persons (Level 2) variables were included to determine whether they had an impact on the mother–child relationship at the start of the study (intercept), on rates of change in relationship prior to high school exit (time slope), or on differences in rates of change after high school exit (change in slope after exit). Maladaptive behaviors and residential status at each time point were controlled in the second set of models. Dichotomous predictors were centered at 0 (e.g., female = .5 and male = -.5) and continuous variables (family income, unmet service needs) were grand mean centered.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means and standard deviations for the dependent variables and time-varying covariates at each time point are presented in Table 1. Visual examination of the means suggested that mother–child positive affect and warmth were likely staying the same over time, and maternal burden was decreasing (i.e., a reduction in burden). Furthermore, maladaptive behaviors appeared to be improving (decreasing in severity) over the study period and considerably fewer young adults with ASD were living with their families over time. Note, however, that these overall average patterns may obscure individual differences and high school exit effects, which are the focus of the present study, and which are modeled below.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for within-persons variables by wave of measurement.

| Variable | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Outcomes | ||||||||

| Mother–child positive affect | 23.42 | 3.76 | 23.11 | 3.69 | 24.13 | 3.53 | 24.38 | 3.76 |

| Subjective burden | 36.70 | 9.43 | 36.61 | 8.82 | 35.17 | 9.24 | 34.00 | 9.09 |

| Warmth | 3.05 | 1.23 | 3.31 | 1.12 | 3.23 | 1.02 | 3.17 | 1.22 |

| Time-varying covariate | ||||||||

| Maladaptive behaviors | 114.85 | 10.34 | 114.49 | 11.02 | 113.04 | 10.93 | 111.01 | 10.10 |

| Proportion living outside of parental home | .18 | .38 | .21 | .41 | .29 | .46 | .45 | .50 |

| Total N for dependent variables | 164–170 | 126–153 | 115–138 | 103–114 | ||||

Correlations within the constructs of mother–child positive affect and burden were high over time, ranging from .79 (Time 2 to Time 3 mother–child positive affect) to .59 (Time 2 to Time 5 positive affect). Correlations over time were moderate for maternal warmth (ranging from .74 to .32); these data are available from the first author. In general, the within-construct correlations were as expected, with measurements taken closer together in time being more highly correlated than measurements taken further apart.

Indices of the mother–child relationship were moderately correlated with each other, with coefficients ranging from −.54 (Time 5 burden and positive affect) to −.29 (Time 3 burden and warmth). In most cases correlations between the measure coded from the FMSS (warmth) and maternal report measures (mother–child positive affect and burden) were just as strong as the correlations within each data collection method. The moderate correlations between these indices suggest that mother–child positive affect, burden, and warmth are related to each other but yet are conceptually distinct.

Unconditional Growth Models

For all growth models, time relative to the start of the study was coded as the number of years since Time 2 for each sample member based on the exact date of measurement. Time 2 was coded as 0, the mean for Time 3 was 1.58 (range from 1.12 to 2.39), the mean for Time 4 was 3.17 (range from 2.49 to 4.40), and the mean for Time 5 was 7.00 (range from 6.05 to 8.17). An additional time variable—the number of years since high school exit—was also included in these models. At Time 2 (the first point of data analysis in the present study), all youth with ASD were in high school. Twenty-five young adults exited high school between Time 2 and Time 3, 26 left between Time 3 and Time 4, and 50 left between Time 4 and Time 5. For all time points before high school exit for each individual, the ‘time since exit’ variable was coded as 0. For all time points after high school exit for each individual, the exit date was subtracted from the date of data collection to indicate the number of years that had passed since exit. These growth curve models estimate three parameters: mother–child relationship at Time 2 (intercept), slopes of relationship variables prior to high school exit, and changes in slopes of relationship variables after high school exit.

Results of the three unconditional growth models, which allowed us to estimate the average change in the mother–child relationship for the sample prior to and after high school exit, are presented in Table 2. All of the measures of the mother–child relationship were significantly improving prior to high school exit. However, for both maternal burden and warmth, improvement significantly slowed after high school exit. Specifically, although burden was decreasing while the son or daughter was in high school (by .58 points/year), after high school exit reductions in burden slowed to nearly one-tenth the rate while in high school (−.06 points/year or −.58 + .52). In terms of warmth, mothers were becoming warmer over time while youth with ASD were in high school (.06 points/year), but were becoming less warm over time after high school exit (−.06 points/year or .06 + −.12). Increases in mother–child positive affect did not change after high school exit (i.e., they continued increasing at the same rate).

Table 2. Unstandardized coefficients from multilevel growth models of rates of change before high school exit and rates of change after exit in the mother–child relationship.

| Mother–child positive affect (n = 168) | Subjective burden (n = 170) | Warmth (n = 166) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Before adding within-persons covariates | ||||||

| Initial status intercept (Random) | 23.30** | .28 | 36.87** | .69 | 3.08** | .09 |

| Slope prior to high school exit (Random) | .27** | .06 | −.58** | .15 | .06* | .02 |

| Change in slope after high school exit (Random) | −.22 | .12 | .52* | .26 | −.12** | .04 |

| After adding within-persons covariates | ||||||

| Initial status intercept (Random) | 23.65** | .30 | 35.26** | .65 | 3.12** | .10 |

| Slope prior to high school exit (Random) | .20** | .06 | −.30* | .12 | .04 | .02 |

| Change in slope after high school exit (Random) | −.25* | .11 | .67** | .22 | −.13** | .04 |

| Maladaptive behaviors (Fixed) | −.09** | .01 | .36** | .04 | −.03** | .00 |

| Lives outside parental home (Fixed) | .73 | .39 | −3.70** | .93 | −.03 | .12 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Controlling for Changes in Residential Placement and Maladaptive Behaviors

Because maladaptive behaviors are highly correlated with measures of the mother–child relationship (Beck et al. 2004; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006; Lam et al. 2003; Orsmond et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008), we hypothesized that the slowing in improvement in burden and warmth after high school exit may be accounted for changes in maladaptive behaviors at this time relative to while youth with ASD were in high school (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a). Furthermore, for some young adults with ASD, moving out of the parental home occurs concurrent with or near in time to exiting the secondary school system. It is possible, then, that changing living arrangements, and not exiting high school per se, accounts for the attenuation of improvement in the mother–child relationship. In order to test these hypotheses, we re-estimated the unconditional models with the inclusion of maladaptive behaviors and residential status (living in the home or out of the home) at each time point as fixed time-varying covariates. If changes in maladaptive behaviors or residential status were responsible for the reduction in improvement, then controlling for these variables over time would explain the changes in burden and warmth, resulting in a non-significant or attenuated change in slope after exit. The bottom of Table 2 displays coefficients from these models.

As expected, changes in maladaptive behaviors were strongly related to concurrent changes in all indices of the mother–child relationship. Mothers whose son or daughter had more maladaptive behaviors had significantly less positive affect in the mother–child relationship, more burden, and less warmth. Changes in residential status of the son or daughter were also related to subjective burden; mothers reported lower burden when their son or daughter was not living with them.

After adding in the time-varying covariates, all of the changes in slope after high school exit that were statistically significant in the prior set of models remained so, suggesting that the attenuation of improvement in the mother child relationship after high school exit was not merely a result of change in maladaptive behaviors or residential status. For two variables, the change in slope after high school exit became even stronger. Before the addition of the time-varying covariates, maternal burden changed from a decrease of .58 points/year while in high school to little change over time after high school exit (−.06 points/year). However, after controlling for changes in maladaptive behaviors and residential status, burden changed from decreasing at .30 points/year while in high school to increasing at .37 points/year after exit. Furthermore, the change in slope of mother–child positive affect after high school exit, which was not significant in the unconditional models, was statistically significant after the addition of the time-varying covariates. Although mothers were reporting increasing positive affect while their son or daughter was in high school at a rate of .20 points/year, positive affect was declining after exit at a rate of .05 points/year when controlling for concurrent changes in maladaptive behaviors and residential placement.

Adding Between-Persons Variables

In the next series of models, the effects of between-persons (Level 2) covariates on initial status and change in the mother–child relationship measures were tested. Three separate models were run, one for each measure. Adding the between-persons variables into the models allowed us to examine three questions: (1) Do the Time 2 measures of the mother–child relationship depend on ID status, child's gender, family income, or unmet service needs while in high school? (2) Do changes over time in the mother–child relationship, prior to high school exit, depend on ID status, child's gender, family income, or unmet service needs? (3) Do any differences in change after high school exit depend on these same between-subjects variables? Finally, maladaptive behaviors and residential status at each time point were controlled by entering them into the models as fixed, time-varying covariates.

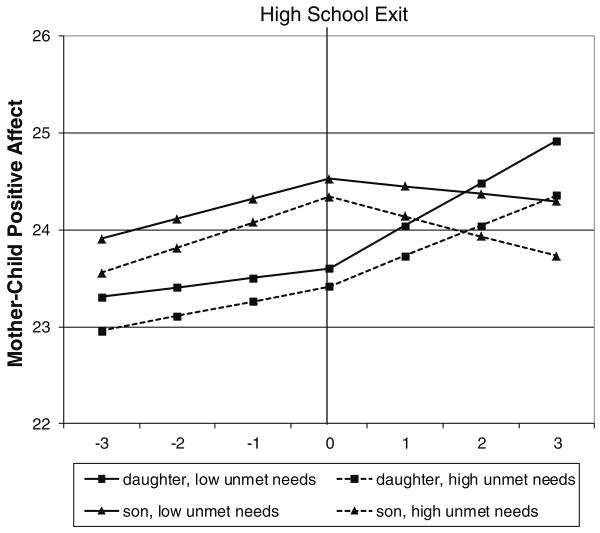

Table 3 presents the coefficients and standard errors from the multilevel models that included between-persons factors. In terms of mother–child positive affect, mothers who had lower family incomes reported greater initial positive affect at Time 2 (reflected in the initial status intercept). Although none of the between-subjects variables predicted change in mother–child positive affect while the person with ASD was in high school, both the gender of the young adult with ASD and unmet service needs while in the secondary school system predicted changes in the slope of mother–child positive affect after high school exit. Figure 1 depicts the change in positive affect for mothers of sons versus daughters, as well as for families with lower unmet service needs (at the 25th percentile or equivalent to 1 unmet need) and higher unmet needs (at the 75th percentile or equivalent to 3 unmet needs). Mother–child positive affect was increasing after high school exit for mothers of daughters (.38 points/year) but was declining after exit for mothers of sons (−.14 points/year). Furthermore, exiting high school had a greater negative impact on changes in mother–child positive affect when the son or daughter had high unmet service needs (relative to low unmet needs).

Table 3. Unstandardized coefficients from multilevel models incorporating between-persons effects on initial status and rates of change (pre-exit and post-exit) of the mother–child relationship.

| Mother–child positive affect | Subjective burden | Warmth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Initial status intercept (Random) | 23.41** | .37 | 35.03** | .76 | 3.05** | .12 |

| Intellectual disability | .60 | .55 | 1.85 | 1.20 | .20 | .19 |

| Daughter | −.60 | .66 | .31 | 1.34 | −.17 | .22 |

| Family income | −.18* | .09 | −.07 | .19 | −.01 | .03 |

| Unmet service needs | -.11 | .12 | .86** | .26 | −.01 | .04 |

| Slope prior to high school exit (Random) | .18** | .07 | −.29* | .15 | .06 | .03 |

| Intellectual disability | −.08 | .12 | .26 | .27 | −.14** | .05 |

| Daughter | −.11 | .13 | .23 | .28 | −.04 | .06 |

| Family income | −.02 | .02 | −.03 | .04 | −.01 | .01 |

| Unmet service needs | .03 | .03 | −.03 | .06 | −.00 | .01 |

| Change in slope after high school exit (Random) | −.07 | .13 | .50 | .27 | −.17* | .05 |

| Intellectual disability | .15 | .22 | −.67 | .45 | .19* | .09 |

| Daughter | .63* | .24 | −.75 | .53 | −.01 | .10 |

| Family income | .01 | .04 | .13 | .08 | .02 | .01 |

| Unmet service needs | −.09* | .05 | .02 | .09 | .00 | .02 |

| Maladaptive behaviors (Fixed) | −.08** | .01 | .33** | .03 | −.02** | .01 |

| Lives outside parental home (Fixed slope) | .71 | .40 | −3.95** | .96 | −.01 | .11 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Fig. 1.

Conditional growth curve model for mother–child positive affect with significant between-persons covariates depicted. Triangles represent sons with ASD and squares represent daughters. Solid lines represent those with low unmet service needs (25th percentile or 1 unmet need) and dotted lines represent those with high unmet needs (75th percentile or over 3 unmet needs)

Higher unmet service needs predicted more maternal subjective burden at Time 2; however, none of the between-persons variables predicted change in burden either before or after high school exit. Thus, increasing maternal burden after their son or daughter left high school was evident regardless of the ID status or gender of the son or daughter, family income, or the number of unmet service needs while the youth with ASD were in the secondary school system.

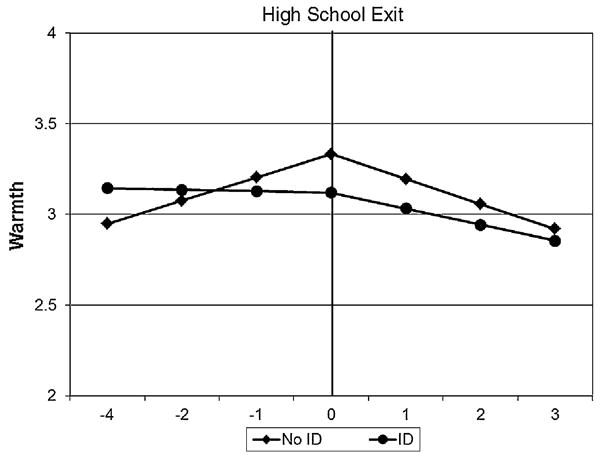

Whether or not the son or daughter with ASD had comorbid ID predicted change in maternal warmth both before and after high school exit. Figure 2 depicts the change in warmth for mothers of those with and without ID. For mothers of youth with ASD with comorbid ID, exiting high school had little impact on changes in maternal warmth over time. Warmth was essentially staying the same over time while these youth were in high school (−.01 points/year), with a slight decrease over time after high school exit (−.09 points/year). On the other hand, high school exit had a larger impact on changes in warmth for mothers of youth with ASD without ID. Before exit, maternal warmth was increasing at a rate of .13 points/year. After exit, however, warmth was declining at a rate of −.14 points/year.

Fig. 2.

Conditional growth curve model for warmth with the significant between-persons covariate depicted. Circles represent those with ASD who have comorbid ID, and diamonds represent those with ASD without comorbid ID

Discussion

This study provides additional evidence to suggest that the years after high school exit are a time of great risk for youth with ASD and their families. Consistent with our research finding that improvement in the autism behavioral phenotype slows and even reverses after high school exit (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a), the present analyses found parallel arrests in improvement in aspects of the mother–child relationship during this time—especially for those who do not have ID and who have more unmet service needs while in high school. Perhaps most interesting, the negative impact of high school exit on changes in this relationship became even more pronounced after controlling for changes in maladaptive behaviors, which are highly correlated with the mother–child relationship (Beck et al. 2004; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006; Lam et al. 2003; Orsmond et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008), and when controlling for coresidence. A mother–child relationship that is becoming less positive over time coupled with slowing of improvements in the behavioral phenotype may place youth with ASD at high risk for poor outcomes in the years immediately following their exit from the secondary school system, and possibly beyond.

It appears that youth with ASD who do not have a comorbid ID may be at particularly high risk for problems in the mother–child relationship after high school exit. Maternal warmth was decreasing more after exit for mothers of youth with ASD without ID relative to those with ID. Our previous research has also found evidence that youth with ASD without ID may be at higher risk during the years after exit. We found greater slowing of phenotypic improvements for these individuals (Taylor and Seltzer 2010a), and those without ID were more likely to have no occupational/educational activities after high school exit relative to youth with comorbid ID (Taylor and Seltzer 2010b). The decreases in warmth after high school exit for youth with ASD without ID may reflect family frustrations stemming from difficulty in finding appropriate day activities for them.

However, the specificity of the relation between ID status and warmth, but not maternal burden or mother–child positive affect, suggests that the impact of high school exit on the mother–child relationship may reflect more than just problems finding appropriate day activities. These findings may also indicate a difference in behavioral attributions between mothers of youth with ASD who do and do not have ID. Mothers whose son or daughter with ASD is higher functioning (i.e., who does not also have ID) may be more likely to attribute the youth's maladaptive behaviors as being under his or her control relative to mothers of lower functioning individuals, who may be more likely to attribute their son or daughter's behaviors to causes outside of their child's control (such as their disability). Attributions of control are related to higher levels of criticism and lower levels of warmth (for reviews see Barrowclough and Hooley 2003; Wearden et al. 2000) but, to the best of our knowledge, attributions of control have not been shown in past research to be related to burden or the degree of positive affect in parent–child relationships. Thus, the decreases in warmth for mothers of youth with ASD who do not have ID may reflect a propensity toward making attributions of control about the son or daughter's behavior. Maternal attributions about their son or daughter's difficult behaviors during the transition to adulthood should be further studied, as they provide a malleable point of intervention to improve the mother–child relationship. Additionally, maladaptive behaviors should also be the target of interventions, even during late adolescence and young adulthood, as they too have a large impact on the quality of the mother–child relationship as well as the quality of life of the individual with ASD.

Maternal and family expectations may also help explain the greater negative impact of high school exit on the mother–child relationship for youth with ASD without ID relative to those with ID. Although youth with ASD without ID are more likely to attend college, live, and work independently relative to those with ID (Eaves and Ho 2008; Farley et al. 2009; Gillberg and Steffenburg 1987; Howlin et al. 2004; Taylor and Seltzer 2010b), many youth do not obtain these developmental milestones (Taylor and Seltzer 2010b). Less positive parent–child relationships after exit for those without ID might reflect parents' high expectations for their son or daughter's young adult lives (living independently, finishing college) that are not met.

Gender played an important role in changes in mother–child positive affect after high school exit. After exit, mothers of daughters with ASD reported greater increases in positive affect in the mother–child relationship over time, relative to mothers of sons. Similar results were found in our earlier study examining change in mother–child positive affect (Lounds et al. 2007); the present study extends this work by finding that the gender effect was specific to the years after high school exit. That is, gender did not predict the initial status of mother–child positive affect nor the change in positive affect while youth were in high school. It may be that in the years after high school exit for youth with ASD, mother–child relationships begin to more closely mirror those in the general population, with mothers reporting more closeness to daughters than to sons (Rossi and Rossi 1990; Ryff and Seltzer 1996).

Finally, more unmet service needs while youth with ASD were still in the secondary school system predicted less positive change in mother–child positive affect after high school exit. Similar to the effect of gender, unmet service needs while in school did not predict concurrent changes in positive affect, but instead predicted changes after high school exit. Because of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which mandates appropriate educational services for all individuals, youth with ASD generally have at least some of their service needs met while they are in high school. There is no such guarantee, however, after they exit school and enter the adult service world. Those youth who already have high numbers of unmet needs while in school may be at a greater risk for high unmet needs and limited employment/occupational activities after high school exit. Thus, unmet service needs while in the secondary school system may prove to be a useful early marker in identifying those youth who later may be at risk for family stress after high school exit. Future research should continue to explore the impact of service receipt and needs while in high school on services after exit, as well as how services may impact the functioning of the youth with ASD as well as family functioning.

It is important to note that our findings do not suggest that services are interchangeable, nor that a greater number of generic disability services will improve the functioning of youth with ASD or their families. For example, it may be that the most significant service families receive through the school system is “respite”—that is, a place for their son or daughter to spend the majority of their day. The loss of this type of respite likely has more of an impact on maternal functioning and the mother–child relationship than, for example, loss of speech therapy services. It is thus critically important to examine and understand which specific services promote positive development for youth with ASD and for their families, both before and after high school exit.

There are four limitations to the present study that are worth noting. First, the sample in the larger study was a volunteer sample, most of the sample members were Caucasian, and the sample was skewed toward those with higher SES. These factors place limits on the generalizability of the results to non-White and lower SES populations. Second, because this was not an experimental study, it is impossible to determine whether exiting high school is the causal factor in relationship change. Although we ruled out residential change and changes in maladaptive behaviors concurrent with exit as competing explanations, there could be a number of other factors associated with high school exit causing problems in the mother–child relationship. Third, some of the significant changes were small in magnitude.

Finally, we were unable to examine disability services after high school exit as we did not measure this variable after Time 2. Unmet service needs while youth are in the secondary school system may not impact changes in the mother–child relationship directly, but instead may lead to unmet service needs after youth with ASD leave high school, and thus may indirectly affect the mother–child relationship. Future research should study the interrelationships between exiting high school, services received before and after exit, vocational activities of the youth with ASD after high school exit, and family functioning. Only comprehensive studies of this sort will allow us to untangle the complicated influences of services received and unmet service needs on post-high school outcomes for youth with ASD and their families.

These limitations are offset by a number of strengths. This is the first longitudinal study to examine the mother–child relationship for mothers of youth with ASD focusing on the transition out of high school, allowing us to prospectively examine how this turning point is associated with changes in the relationship. Although there are limits to its generalizeability, our sample was relatively large and recruited from the community, making our findings more generalizeable than many other studies of families of individuals with ASD which were recruited from clinical populations. Third, the mother–child relationship was measured using a multi-method approach (self-reports and independently coded speech samples), limiting the influence of shared method variance. Finally, this is the first empirical study to provide evidence that exiting high school is a disruptive influence in the lives of these families, which has long been suspected but not yet empirically demonstrated. Future research should consider the individual, family, and structural factors that promote optimal family functioning and adult outcomes for youth with ASD after exiting the school system, in order to develop interventions and provide services that can smooth this process and improve the quality of life of youth with ASD and their families.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Marino Autism Research Institute (J.L. Taylor, PI), the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG08768, M.M. Seltzer, PI) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD15052, E.M. Dykens, PI; P30 HD03352, M.M. Seltzer PI).

Contributor Information

Julie Lounds Taylor, Email: Julie.l.taylor@vanderbilt.edu, Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, Peabody Box 40, 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN 37203, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and the Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN, USA.

Marsha Mailick Seltzer, Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

References

- Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck PT, Krauss MK, Orsmond GI, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with Autism, down syndrome, of Fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;103:237–254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Hooley JM. Attributions and expressed emotion: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:849–880. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Daley D, Hastings RP, Stevenson J. Mothers' expressed emotion towards children with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2004;48:628–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Allen KR. The life course perspective applied to families over time. In: Boss P, Doherty W, LaRossa R, Schumm W, Steinmetz S, editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 469–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Schrader SS. Parent-child relationships. In: Mangon DJ, Peterson WA, editors. Research instruments in social gerontology. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1982. pp. 115–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma R, Schweitzer R. The impact of chronic childhood illness of family stress: A comparison between autism and cystic fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;46:722–730. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199011)46:6<722::aid-jclp2270460605>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock RW, Weatherman RF, Hill BK. Scales of independent behavior revised. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson SE, Smith IM. Epidemiology of autism: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and implications for research and service delivery. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1998;4:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff R, Hooley J. Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:547–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffit T, Morgan J, Rutter M, Taylor A, Arseneault L, et al. Maternal expressed emotion predicts children's antisocial behavior problems: Using monozygotic-twin differences to identify environmental effects on behavioral development. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:149–161. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan AM. Family stress and ways of coping with adolescents who have handicaps: Maternal perceptions. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1988;92:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossetor DR, Nichol AR, Stretch DD, Rajkhowa SJ. A study of expressed emotion in the parental primary carers of adolescents with intellectual impairment. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1994;38:487–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1994.tb00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Wolf LC, Fisman SN, Culligan A. Parenting stress, child behavior problems, and dysphoria in parents of children with autism, Down syndrome, behavior disorders, and normal development. Exceptionality. 1991;2:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Ho HH. Young adult outcomes of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:739–747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley MA, McMahon WM, Fombonne E, Jenson WJ, Miller J, Gardner M, et al. Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average of near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research. 2009;2:109–118. doi: 10.1002/aur.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: An update. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong L, Wilgosh L, Sobsey D. The experience of parenting an adolescent with autism. International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education. 1993;40:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Fletcher JM, Steubing KK, Davidson KC, Thompson NM. Analysis of change: Modeling individual growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:27–37. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Furstenberg FF. The transition to adulthood during the twentieth century. In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Steffenburg S. Outcome and prognostic factors in infantile autism and similar conditions: A population-based study of 46 cases followed through puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987;17:273–287. doi: 10.1007/BF01495061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glutting JJ, Adams W, Sheslow D. Wide range intelligence test. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Hong J, Orsmond GI. Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:229–249. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[229:BEOEEA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Chou RJ, Hong J. The effect of quality of the relationship between mothers and adult children with disabilities: The mediating role of optimism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:14–25. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg K, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH, Magana AB, Mintz J, Doane JA, et al. Expressed emotion and patient-relative interaction in families of recent onset schizophrenics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:11–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C, Beck A. Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:48–61. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[48:MDAEEC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd J, McArthur D. Mental retardation and stress on the parents: A contrast between Down's syndrome and childhood autism. American Journal on Mental Deficiency. 1976;80:431–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P. Outcomes in autism spectrum disorders. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and developmental disorders, vol 1: Diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Alcock J, Burkin C. An 8 year follow-up of a specialist supported employment service for high-ability adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2005;9:533–549. doi: 10.1177/1362361305057871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with Autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell J, Fischer JL, Dunham RM, Baranowski M. Parents and adolescents: Push and pull of change. In: McCubbin HI, Figley DR, editors. Stress in the family: Coping with normative transitions. New York: Bruner; 1983. pp. 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss MW, Seltzer MM, Jacobson HT. Adults with autism living at home or in non-familial settings: Positive and negative aspects of residential status. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Giles A, Lavender A. Carers' expressed emotion, appraisal of behavioural problems and stress in children attending schools for learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: Data from the national survey of children's health. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29:152–160. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318165c7a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal on Mental Retardation. 1994;112:401–417. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounds J, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Shattuck PT. Transition and change in adolescents and young adults with autism: Longitudinal effects on maternal well-being. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:401–417. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[401:TACIAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy S, Buntinx WHE, Coulter DL, Craig EM, Reeve A, et al. Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. 10th. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1480–1486. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Lau A, Valeri S, Weisz J. Parent-child interactions in relation to critical and emotionally overinvolved expressed emotion (EE): Is EE a proxy for behavior? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:83–93. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000007582.61879.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montemayor R, Eberly M, Flannery DJ. Effects of pubertal status and conversation topic on parent and adolescent affective expression. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:431–447. [Google Scholar]

- Moore E, Kuipers E. The measurement of expressed emotion in relationships between staff and services users: The use of short speech samples. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:345–356. doi: 10.1348/014466599162953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G, Seltzer M, Greenberg J, Krauss M. Mother-child relationship quality among adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:121–137. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[121:MRQAAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue JR, Morgan SB, Geffken GR. Families of autistic children: Psychological functioning of mothers. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;19:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. New York: de Gruyter; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Seltzer MM, editors. The parental experience at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Taylor JL, Smith L, Orsmond GI, Esbensen A, Hong J. Adolescents and adults with Autism spectrum disorders. In: Amaral DG, Dawson G, Geschwind DH, editors. Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Orsmond GI, Vestal C. Families of adolescents and adults with autism: Uncharted territory. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2001;23:267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Shattuck PT, Orsmond G, Swe A, Lord C. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:565–581. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005995.02453.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and even occurrence. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC. Aging families of adults with mental retardation: Patterns and correlates of service use, need, and knowledge. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1997;102:13–26. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1997)102<0013:AFOAWM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Greenberg J, Seltzer M, Hong J. Symptoms and behavior problems of adolescents and adults with autism: Effects of mother-child relationship quality, warmth, and praise. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:387–402. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:387-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Carter AS, Cicchetti DV. Vineland screener: Overview, reliability, validity, administration, and scoring. New Haven: Yale University Child Study Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens MP, Kinney JM. Caregiver stress instruments: Assessment of content and measurement quality. Gerontology Review. 1989;2:40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Ward J, Donaldson C, Burns A, Gregg L. Expressed emotion and attributions in the carers of patients with Alzheimer's disease: The effect of carer burden. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:340–349. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Changes in the autism behavioral phenotype during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010a;40:1431–1446. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Employment and postsecondary education activities for young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010b doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1902–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Humbeeck G, Van Audenhove C, De Hert M, Pieters G, Storms G. Expressed emotion: A review of assessment instruments. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:321–341. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn CE, Leff JP. The influence of family and social factors on the course of psychiatric illness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1976;129:125–137. doi: 10.1192/bjp.129.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearden A, Tarrier N, Barrowclight C, Zastowny T, Rahill A. A review of expressed emotion research in health care. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:633–666. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman A, Lopez SR, Karno M, Jenkins J. An attributional analysis of expressed emotion in Mexican-American families with schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:601–606. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf LC, Noh S, Fisman SN, Speechley M. Psychological effects of parenting stress on parents of autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1989;19:157–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02212727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SM, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH. Relatives' affective style and the expression of subclinical psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia. Family Process. 2004;43:233–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist. 1980;20:649–655. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]