Abstract

In the pediatric literature, excessive crying has been reported solely in association with 3-month colic and is described, if at all, as unexplained crying and fussing during the first 3 months of life. The bouts of crying are generally thought to be triggered by abdominal colic (over-inflation of the still immature gastrointestinal tract), and treatment is prescribed accordingly. According to this line of reasoning, excessive crying is harmless and resolves by the end of the third month without long-term consequences. However, there is evidence that it may cause tremendous distress in the mother-infant relationship, and can lead to disorders of behavioral and emotional regulation at the toddler stage (such as sleep and feeding disorders, chronic fussiness, excessive clinginess, and temper tantrums). Early treatment of excessive crying focuses on parent-infant communication, and parent-infant interaction in the context of soothing and settling the infant to sleep is a promising approach that may prevent later behavioral and emotional disorders in infancy.

Keywords: Excessive crying, Behavioral and emotional regulation disorder, Infant

Introduction

An infant's crying has 2 possible consequences: it may elicit tenderness and desire to sooth, or helplessness and rage. It can be a signal that encourages attachment or one that jeopardizes the early relationship by triggering depression and, in some cases, even neglect or abuse.

According to the Heird, colic is a symptom complex of paroxysmal abdominal pain, presumably of intestinal origin, and severe crying. It usually occurs in infants younger than 3 months of age1). The paroxysms may persist for several hours. The fact that the condition rarely persists beyond 3 months of age should be reassuring.

However, the more persistent problems of colicky babies have recently been given a new name: disorders of behavioral and emotional regulation. The clinical evidence of these disorders is observed during the first years of life within the developing systems of parent- infant communication, attachment, and early relationships. They comprise a wide spectrum of behavioral syndromes ranging from early excessive crying, sleep and feeding disorders, failure to thrive, and problems of attention and emotional regulation, to disturbances in the regulatory balance between attachment and exploration and/or between dependence and autonomy in the second and third years of life2,3).

They are characterized by the co-occurrence or sequential occurrence of different behavioral syndromes. Many problems that typically emerge during the second half-year of life or in later phases of early childhood development actually have precursors in the first half-year, mostly in the form of excessive crying and dysfunctional sleep-wake organization. Without timely intervention, these early disorders tend to persist and to pervade other behavioral domains. It is therefore important not to underestimate early excessive crying and to offer timely help with targeted counseling or even parent-infant psychotherapy.

Critical moments in childhood development

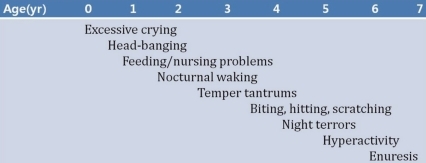

Fig. 1 lists some of the developmental and behavioral problems that are often observed during the first few years of life. Each problem tends to occur most frequently at a particular age4). For example, excessive crying typically occurs during the first 3 months; biting, scratching, or hitting other children is more likely to be seen when a child is between 2 and 5 years old.

Fig. 1.

Typical developmental difficulties during the early years.

According to the scientific literature, development in infancy is not continuous, but alternates between periods of consolidation and development spurts that are also termed biobehavioral shifts, touchpoints, critical steps, or periods of qualitative transition. The concept of touchpoints5) postulates sensitive periods shortly before each impending developmental shift (around 3, 9, 12, and 18 months), in which critical regulatory tasks must be completed.

The predominance of certain syndromes at certain ages and the age-related course of these syndromes coincide remarkably well with the postulated touchpoints6).

Each developmental phase places new demands on the infant's capacity to regulate, which depends on the structural and functional maturity of the brain as well as the accumulated experiences that have already been integrated.

The first biopsychosocial shift promotes regulation at a higher level of integration around the ages of 2 and 3 months. Emde and Osofsky7) have stressed the emerging social capabilities (persistent eye contact, social smiling, and melodious cooing) as the "awakening of sociability." This preverbal communication provides a framework for practicing reciprocal regulation of attention, positive affective arousal, and self-efficacy.

Another developmental shift occurs in the middle of the second half-year (around 9 months), during which canonical babbling begins, and object permanence, intentionality, fear of strangers, and crawling, among other things, occur at more or less the same time8). The beginning of independent locomotion allows for the child's growing need for exploration, as well as its opposite: an increased need for closeness.

A third biopsychosocial developmental shift begins around the middle of the second year of life and brings with it new regulatory challenges for both toddlers and parents. Independent walking offers a child an almost limitless range of exploration. Symbolic play and a spurt in vocabulary mark new levels of symbolization, language-mediated integration of experience, imagination, and representations of the self and attachment figures. At a motivational level, the interplay between the growing need for autonomy and the need for reassurance is first and foremost; in communication, it is the balance between dependency and autonomy, and the negotiation of social rules and limits.

Database of the Munich interdisciplinary research and intervention program for fussy babies

Between the opening of the Munich program in 1991 and 2004, approximately 3,000 families were referred for diagnostic assessment, counseling, and treatment of fussy babies. The data of 701 families was analyzed9).

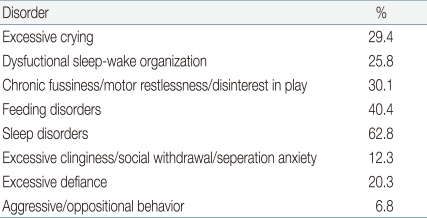

1. Clinical syndromes of behavioral and emotional regulation

At the first visit, the most frequent problems that concerned parents were sleep disorders; feeding disorders; dysphoric fussiness/disinterest in play (hereafter referred to as dysphoric fussiness); excessive crying; dysfunctional sleep-wake organization; excessive temper tantrums with conflicts over limit setting (hereafter referred to as excessive defiance); excessive clinginess with anxiety, social withdrawal, and/or intense separation anxiety (hereafter referred to as excessive clinginess); and aggressive/oppositional behavior (Table 1)9).

Table 1.

Disorder of Behavioral and Emotional Regulation in Early Childhood (n=701)

Most of the behavioral problems of early childhood are not distributed evenly across all ages, but are clustered in particular developmental phases. For example, excessive crying and dysfunctional sleep-wake organization are more or less confined to the first half-year of life, whereas sleep disorders were, by definition, diagnosed only above the age of 6 months.

2. Phase specificity of clinical syndromes

The predominance of certain syndromes at certain ages and the age-related course of these syndromes coincide remarkably well with the postulated touchpoints9). For example, excessive crying predominates during the first 3 months (97.3% of that age group), during which postnatal adjustments and maturation of physiological processes are predominant. This behavior is being seen less frequently over the rest of the first year.

Dysphoric fussiness increases in frequency over the first 9 months, and thus seems to replace excessive crying. The rapid increase in the frequency of dysphoric fussiness, up to its peak in the middle of the second half-year, coincides with a developmental phase in which affective and attentional regulatory processes and exploratory needs are predominant during the waking state.

Dysfunctional sleep-wake organization is typically associated with excessive crying in the first 3 months (95.5% of age group). At around the sixth month of life, diurnal problems of sleep-wake organization give way to nighttime sleep disorders, which are the most frequent diagnoses in all age cohorts.

Excessive clinginess peaks during the fourth quarter of the first year (21.4% of the age group) and it remains a reason for referral during the second year. Excessive clinginess appears as the child's attachment to his primary caregivers becomes established, and fear of strangers and separation anxiety emerge.

3. Early signs of later clinical syndromes

Investigators found associations between excessive crying during the first months of life and later behavioral problems, such as feeding problems in the first and second years of life10) and sleep disorders in the second11) and third years of life12).

Wurmser and Papousek9) found clear indications that the clinical syndrome of excessive crying in early infancy is a precursor of clinically significant behavioral and emotional problems at 30 months. According to their data, excessive crying and feeding disorders also preceded later sleep disorders in 64.3% and 20.0% of infants, respectively. Excessive crying and dysfunctional sleep-wake organization preceded later feeding disorders in 55.5% and 59.2% of cases, respectively. Moreover, excessive crying in combination with dysfunctional sleep-wake organization was also evident within the first half-year of life in children with later excessive clinginess (69.5% of 82) and excessive defiance (64.8% of 142).

Excessive crying in infancy

The core symptoms of excessive crying in infants include unexplained, inconsolable crying and long episodes of inexplicable fussiness. Paroxysmal bouts of severe crying, with flexed knees, hypertonic extremities, overinflated abdomen, reddened face, and shrill hyperphonic crying, that do not respond to the usual soothing interventions, naturally make one suspect abdominal pain13). Many of these infants do not snuggle, but instead resist close body contact as if they were trying to struggle against their mother.

1. Definition and diagnostic criteria

According to international consensus, the scientific criteria for differentiating between normal and excessive crying at the age of 6 weeks draw on the "rules of threes": crying and fussing for more than 3 hours a day, for more than 3 days a week, and for more than 3 weeks, in an infant who is well-fed and otherwise healthy14). The syndrome is more appropriately classified as a syndrome of excessive crying and an age-related subgroup of disorders of behavioral and emotional regulation in early childhood. The term "persistent excessive crying" is used when the problem persists beyond the age of 3 months2,3).

The clinical syndrome of excessive crying is characterized by a triad of symptoms. The diagnostic triad includes: 1) the infant's inconsolable crying with problems in sleep-wake organization, 2) the parents' overload and psychosocial distress, and 3) frequent interactional failure that maintains or exacerbates the behavioral problems15).

Excessive crying that persists beyond the developmental spurt expected at the age of approximately 3 months takes on new qualities, depending on the infant's progress in self-regulatory capacities. In addition, problematic crying shifts increasingly to nighttime, when the infant should be asleep. Persistent excessive crying should therefore be distinguished from excessive crying during the first few months of life.

The prevalence of excessive crying during the first 3 months in representative community-based samples has been reported to range between 16% and 29%15-17).

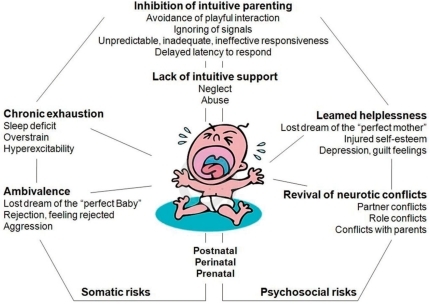

2. A developmental dynamic systems model of the origins and maintenance of excessive crying

The most frequent emotional effects of inconsolable crying on the parent and other caregivers are summarized in Fig. 2. For example, the mother will exhibit all the signs of chronic exhaustion and overload as a consequence of persistent alarm and sleep deficit. The repeated daily experiences of infant inconsolability induce feelings of failure, diminished self-esteem, powerlessness, and depression. Almost all affected parents confess that feelings of helplessness in the face of increasing arousal and alarm occasionally turn into a state of aggressive feelings and powerless rage toward the infant, impulses that in turn evoke intense feelings of guilt and make the parents increasingly vulnerable. The intensity of aroused feelings may finally become fertile ground for the revival of latent conflicts with the partner or other family members, or over the mother's abandoned professional career. Moreover, memories and feelings of abandonment, fear, or rage experienced during the parents' own childhood may easily be evoked in this context.

Fig. 2.

Effects of inconsolable crying on parents and other caregivers.

Hypersensitized by the crying, these parents barely perceive the subtle signals from the infant during more quiet states of alertness, thereby missing opportunities to enter into relaxed dialogue and play. As a consequence, the dysregulated infants will miss the intuitive regulatory support from their parents.

3. Counseling and treatment model of the Munich program

Developmental counseling, psychological and physical relief for the parents, guidance in parent-infant communication, and parent-infant psychotherapy were provided. After conclusion of treatment, the condition was fully improved in 48.4% of the patients and largely improved in 44.2% of the patients, that is, an overall success rate of 92.6%.

Conclusions

Persistence of crying beyond the first 3 months predicts a higher prevalence of behavioral and emotional disorders in children with excessive crying than in children without excessive crying. It is therefore important to offer timely help through developmental counseling, physiotherapy, or even parent-infant psychotherapy.

References

- 1.Heird WC. The feeding of infants and children. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. pp. 214–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papousek M, von Hofacker N. Persistent crying in early infancy: a non-trivial condition of risk for the developing mother-infant relationship. Child Care Health Dev. 1998;24:395–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Kries R, Kalies H, Papousek M. Excessive crying beyond 3 months may herald other features of multiple regulatory problems. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:508–511. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Largo RH, Benz-Castellano C. Critical moments in childhood development: the Zurich fit model. In: Papousek M, Schieche M, Wurmser H, editors. Disorders of behavioral and emotional regulation in the first years of life: early risks and intervention in the developing parent-infant relationship. Washington DC: Zero to Three; 2007. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brazelton TB. How to help parents of young children: the touchpoints model. J Perinatol. 1999;19(6 Pt 2):S6–S7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papousek M. Communication in early infancy: an arena of intersubjective learning. Infant Behav Dev. 2007;30:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emde RN, Osofsky HJ. Bonding, humanism, and science. Pediatrics. 1983;72:749–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant and maternal behaviors regulate infant reactivity to novelty at 6 months. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:1123–1132. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wurmser H, Papousek M. Facts and figures: database of the Munich interdisciplinary research and intervention program for fussy babies. In: Papousek M, Schieche M, Wurmser H, editors. Disorders of behavioral and emotional regulation in the first years of life: early risks and intervention in the developing parent-infant relationship. Washington DC: Zero to three; 2007. pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.St James-Roberts I, Conroy S, Wilsher K. Links between maternal care and persistent infant crying in the early months. Child Care Health Dev. 1998;24:353–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolke D, Meyer R, Ohrt B, Riegel K. The incidence of sleeping problems in preterm and fullterm infants discharged from neonatal special care units: an epidemiological longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;36:203–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rautava P, Lehtonen L, Helenius H, Sillanpää M. Infantile colic: child and family three years later. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1 Pt 1):43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lester BM, Boukydis CF, Garcia-Coll CT, Peucker M, McGrath MM, Vohr BR, et al. Developmental outcome as a function of the goodness of fit between the infant's cry characteristics and the mother's perception of her infant's cry. Pediatrics. 1995;95:516–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wessel MA, Cobb JC, Jackson EB, Harris GS, Jr, Detwiler AC. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called colic. Pediatrics. 1954;14:421–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wurmser H, Laubereau B, Hermann M, Papousek M, von Kries R. Excessive infant crying: often not confined to the first 3 months of age. Early Hum Dev. 2001;64:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(01)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehtonen L, Korvenranta H. Infantile colic. Seasonal incidence and crying profiles. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:533–536. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170180063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St James-Roberts I, Halil T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: normal community and clinical findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991;32:951–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]