Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Drug-induced torsades de pointes (TdP) often occurs during bradycardia due to reverse use-dependence. We tested the hypothesis that inhibition or enhancement of late sodium current (INa,L) could modulate the drug-induced reverse use-dependence in QT and Tp-e (an index of dispersion of repolarization), and therefore the liability for TdP.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Arterially perfused rabbit left ventricular wedge preparations were used. Action potentials from the endocardium were recorded simultaneously with a transmural ECG. The effects of Anemonia sulcata toxin (ATX-II) (an INa,L enhancer), d,l-sotalol, clarithromycin and ranolazine (an INa,L blocker) on rate-dependent changes in QT, Tp-e and proarrhythmic events were tested, either alone or in combination. Rate-dependent QT and Tp-e slopes and TdP score (a combined index of TdP liability) were calculated at control and during drug infusion.

KEY RESULTS

ATX-II (30 nM) and sotalol (300 µM) caused a marked increase in QT and Tp-e intervals, steeper QT-basic cycle length (BCL) and Tp-e-BCL slopes (i.e. reverse use-dependence), and TdP. Addition of ranolazine (15 µM) to ATX-II or sotalol significantly attenuated QT-BCL, Tp-e-BCL slopes and the increased TdP scores. In contrast, clarithromycin (100 µM) moderately prolonged QT and Tp-e without causing R-on-T extrasystole or TdP, but addition of ATX-II (1 nM) to clarithromycin markedly amplified the QT-BCL and Tp-e-BCL slopes and further increased TdP score.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Modulation of INa,L altered drug-induced reverse use-dependence related to QT as well as Tp-e, indicating that inhibition of INa,L can markedly reduce the TdP liability of agents that prolong QT intervals.

Keywords: late sodium current, reverse use-dependence, QT, Tp-e, Tp-e/QT ratio and TdP

Introduction

Torsades de pointes (TdP) is rare but lethal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia seen in the setting of QT interval prolongation. A number of prescription drugs, not limited to antiarrhythmic agents, have been implicated as causing drug-induced QT prolongation and TdP (Antzelevitch, 2004; Joshi et al., 2004; Roden, 2004). Drug-induced TdP has emerged as one of the most significant concerns in drug safety and a major obstacle to new drug development. The last decade was marked by significant progress with respect to elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms of drug-induced TdP (Yan et al., 2001b; Fenichel et al., 2004; Joshi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006). Blockade of the KCNH2-encoded, rapidly activating, delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) is the commonest cause of the drug-induced delayed ventricular repolarization (ion channel nomenclatures follows Alexander et al., 2009). IKr blockers exhibit reverse use-dependence, that is, that the drug-induced repolarization prolongation is more prominent during bradycardia and less during tachycardia, which contributes importantly to arrhythmogenesis (Joshi et al., 2004; Gussak et al., 2007).

Although it is believed that the slowly activating delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs) is an important modulator of rate-dependent ventricular repolarization and plays an important role in reverse use-dependence of certain QT prolonging agents (Jurkiewicz and Sanguinetti, 1993; Yang and Roden, 1996; Salata et al., 1998), accumulating indirect evidence suggests that late sodium current (INa,L), an important inward current during ventricular repolarization, may potentially contribute to rate adaptation of ventricular repolarization and to the reverse use-dependence. It is known that ventricular M cells with a relatively larger INa,L but a smaller IKs exhibit a much steeper rate-dependence of action potential duration (APD) than epicardial and endocardial cells (Antzelevitch et al., 1999; Zygmunt et al., 2001). In transgenic mice with long QT type 3 syndrome in which INa,L is amplified, rate-dependent changes in APD become more prominent (Nuyens et al., 2001). However, the role of INa,L in the reverse use-dependence and its relation to the proarrhythmic liabilities of IKr blockers are not well studied.

Therefore, we planned experiments investigating the role of INa,L in the genesis of TdP induced by IKr blockers, and specifically tested the hypothesis that modulation of INa,L by Anemonia sulcata toxin (ATX-II) or ranolazine can significantly modify the reverse use-dependence of IKr blockers and therefore their proarrhythmic potentials. Specifically, enhancing INa,L by ATX-II could unmask arrhythmogenic effect of non-antiarrhythmic QT prolonging drugs, whereas inhibition of INa,L by ranolazine could attenuate the proarrhythmic potential of Class III antiarrhythmic drugs.

Methods

Arterially perfused rabbit left ventricular wedge preparations

The isolated arterially perfused rabbit left ventricular wedge model was used to test the above hypothesis. This model has been previously validated in a blinded fashion for preclinical assessment of drug-induced proarrhythmias (Liu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008).

All animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Surgical preparation of the rabbit left ventricular wedge has been described in detail in previous publication (Yan et al., 2001a). Briefly, rabbits (New Zealand White) weighing 2.3–2.8 kg in either sexes were anticoagulated with heparin and anesthetized by intramuscular injection of xylazine (5 mg·kg−1) and intravenous administration of ketamine HCl (30–35 mg·kg−1). The chest was opened via a left thoracotomy, and the heart was excised and placed in a cardioplegic solution consisting of cold (4°C) normal Tyrode's solution. The left circumflex branch of the coronary artery was cannulated and perfused with the cardioplegic solution. Unperfused areas of the left ventricle, which were easily identified by their reddish appearance due to the existence of unflushed erythrocytes, were removed. The preparation was then placed in a small tissue bath and arterially perfused with Tyrode's solution containing 4 mM K+ buffered with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (temperature: 35.7 ± 0.1°C, mean perfusion pressure: 35–45 mmHg). The preparation was paced from endocardium (Endo) at basic cycle lengths (BCL) of 2000 ms, 1000 ms and 500 ms. The ventricular wedge was allowed to equilibrate in the tissue bath for 1 h prior to electrical recordings.

Electrophysiological recordings from rabbit ventricular wedge preparations

Transmembrane action potentials were recorded from Endo using a floating glass microelectrode. A transmural ECG signal was recorded using extracellular silver/silver chloride electrodes placed in the Tyrode's solution bathing the preparation 1.0 to 1.5 cm from the epicardial and endocardial surfaces. The QT interval was defined as the time from the onset of the QRS to the point at which the final downslope of the T wave crossed the isoelectric line. The Tp-e interval, which closely approximates transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) (Yan and Antzelevitch, 1998; Liu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008), was defined as the time from the peak to the end of the T wave. QT-BCL and Tp-e-BCL slopes were defined as the changes in QT interval and Tp-e interval as the function of BCL respectively.

The QT and Tp-e intervals were measured manually in three consecutive beats within the last minute of the recording and the values were then averaged.

Late sodium current recording

Late sodium current recording in the single rabbit myocytes has been described in detail in our previous publications. (Guo et al., 2010) Briefly, both fast sodium current (INa,F) and INa,L were recorded at room temperature (22–24°C) using a whole-cell patch-clamp technique. INa,F was recorded during an 80 ms depolarizing voltage step from a holding potential of −100 mV to a test potential of −30 mV. INa,L currents were recorded using a 2000 ms depolarizing pulse from −140 mV to −20 mV at the stimulating rate of 0.1 Hz (holding potential is −140 mV). The amplitude of INa,L was measured at 200 ms after membrane depolarization.

Experimental protocols and endpoint evaluations

The following three groups of experiments were carried out. The sample size of each group was five preparations:

control perfusion for 1 h and then perfusion with ATX-II at 30 nM for 30 min, followed by ATX-II (30 nM) plus ranolazine (15 µM)

control perfusion for 1 h and then perfusion with d,l-sotalol at 300 µM for 30 min, followed by d,l-sotalol (300 µM) plus ranolazine (15 µM)

control perfusion for 1 h and then perfusion with clarithromycin at 100 µM for 30 min, followed by clarithromycin (100 µM) plus ATX-II (1 nM)

The relative TdP risk of each compound was estimated according to the criteria reported previously (Liu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008). The following three core parameters were used in scaling the relative TdP risk of each compound: delayed ventricular repolarization (QT prolongation), dispersion of repolarization (the Tp-e/QT ratio) and the incidence of early afterdepolarization (EAD), with and without closely coupled extrasystoles, and the development of TdP. Among the three parameters, the development of EAD-induced extrasystoles received the greatest weight. TdP score was defined and calculated as described before (Liu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2008). The maximum TdP score was 14 and the minimum TdP score was −2.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Student's t-test or anova (one-way, with post hoc Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test or two-way with Bonferroni test; see Figure legends) as appropriate. The χ2-test was used for the comparison between two groups for event incidences. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Materials

We used ATX-II (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel) to increase the magnitude of INa,L, and a novel anti-anginal drug ranolazine (Sigma, St Louis, USA) was used to reduce INa,L (Antzelevitch et al., 2007). The commonly prescribed antibiotic clarithromycin (Sigma) was chosen as a non-antiarrhythmic IKr blocker(Redfern et al., 2003) as compared with d,l-sotalol (Sigma), a Class III antiarrhythmic drug that blocks IKr.

Results

Effects of ranolazine on INa,L

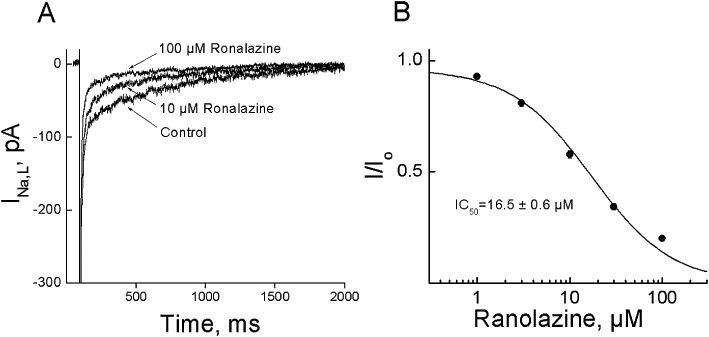

This series of experiments were performed to determine the IC50 of ranolazine on INa,L in the rabbit ventricular myocytes (Figure 1) and, as this was 16.5 ± 0.6 µM (n = 8), we used ranolazine at 15 µM to suppress INa,L in the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effect of ranolazine on late sodium currents (INa,L) in rabbit myocytes. A. The superimposed currents show responses to step depolarizations ranging from −140 to −20 mV from a holding potential of −140 mV, obtained under control conditions and after 3 min of superfusion with various concentrations of ranolazine. B. Concentration–response relationship of ranolazine on INa,L. The amplitude of INa,L was measured at 200 ms after membrane depolarization. Data were fitted with an equation I/Io = 1/(1 +[C]/[IC50]). Data were expressed as Mean ± SEM, n = 8, two cells per rabbit.

Effects of ATX-II, d,l-sotalol and clarithromycin on QT, Tp-e Interval and incidence of proarrhythmic events

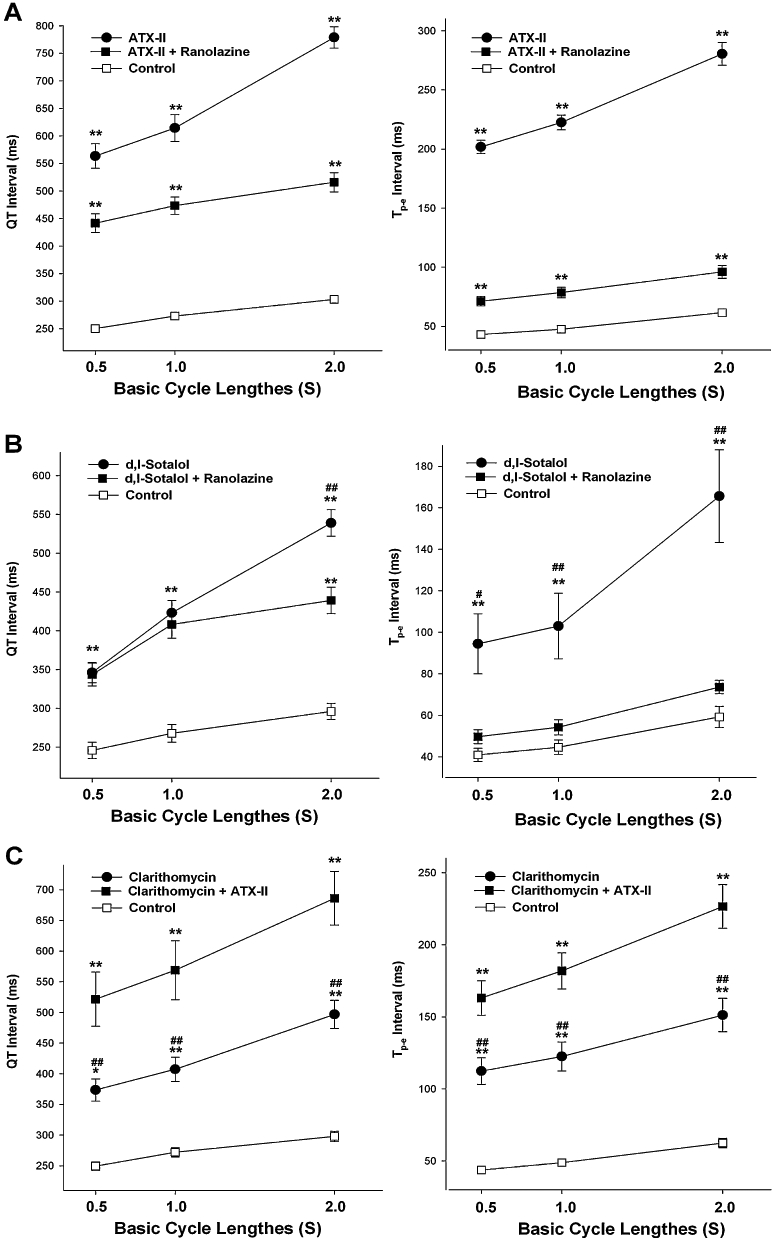

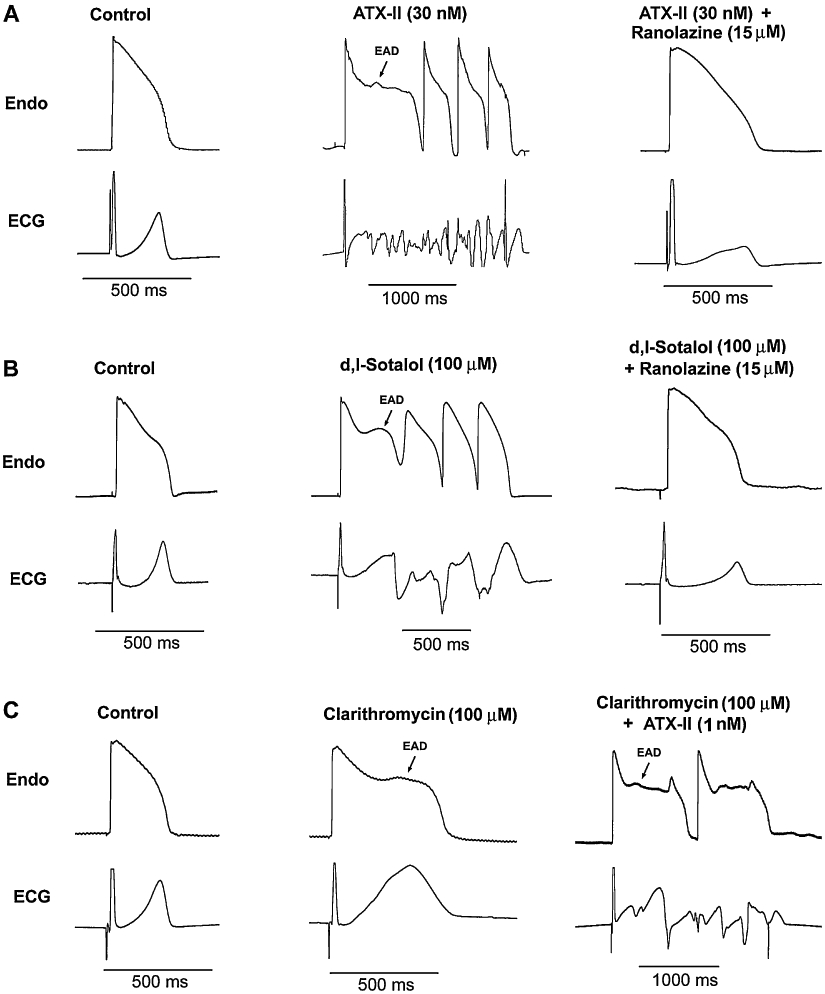

As shown in Figure 2, ATX-II at 30 nM, d,l-sotalol at 300 µM and clarithromycin at 100 µM produced a significant increase in QT and Tp-e intervals, in the preparations paced at a BCL of 2000 ms (Figure 2). Marked QT and Tp-e prolongation by ATX-II and d,l-sotalol during bradycardia, that is, at a BCL of 2000 ms, was associated with the development of R-on-T extrasystoles and TdP (Figure 3, Table 1). Although clarithromycin at 100 µM produced EAD in three of five preparations, no R-on-T extrasystoles and TdP were observed.

Figure 2.

Rate-dependent changes in QT and Tp-e after infusion of ATX-II (30 nM) and ATX-II (30 nM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (A), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and d,l-sotalol (300 µM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (B), and clarithromycin (100 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) plus 1 nM ATX-II (C). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with controls; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 compared with the groups plus additional modulation of INa,L with ATX-II or ranolazine; two-way anova analysis.

Figure 3.

Original tracings of early afterdepolarization (EAD) and spontaneous torsades de pointes (TdP) induced by ATX-II (A), d,l-sotalol (B) and clarithromycin (C), either alone or in combination. Please note that there are different scales. Endo: endocardium; basic cycle length = 2000 ms.

Table 1.

Comparison of the incidence of EADs, R-on-T extrasystole, TdP and TdP score

| Study groups | EADs | R-on-T | TdPs | TdP score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | ATX-II (30 nM) | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 13.6 ± 0.3 |

| ATX-II (30 nM) + Ranolazine (15 µM) | 2/5 | 0/5** | 0/5* | 4.2 ± 1.0** | |

| B | d,l-sotalol (300 µM) | 5/5 | 5/5 | 2/5 | 12.8 ± 0.5 |

| d,l-sotalol (300 µM) + Ranolazine (15 µM) | 3/5 | 0/5** | 0/5 | 3.8 ± 1.2** | |

| C | Clarithromycin (100 µM) | 3/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 8.2 ± 1.2 |

| Clarithromycin (100 µM) + ATX-II (1 nM) | 5/5 | 5/5** | 3/5 | 13.2 ± 0.5* | |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01 compared between the corresponding drug's effects with and without modulation of INa,L within each group.

All arrhythmic events occurred at a basic cycle length of 2000 ms.

ATX-II, Anemonia sulcata toxin; EAD, early afterdepolarization; TdP, torsades de pointes.

Effect of modulation of INa,L on QT, Tp-e interval and incidence of proarrhythmic events

Interestingly, reduction of INa,L by ranolazine at 15 µM significantly attenuated the effects of ATX-II and d,l-sotalol on the QT and Tp-e intervals (Figure 2) In contrast, with infusion of 100 µM clarithromycin, addition of 1 nM ATX-II further increased the QT interval (Figure 2). Ranolazine decreased the incidence of proarrhythmic events including EAD, R-on-T extrasystoles and TdP, whereas ATX-II increased this incidence significantly (Table 1).

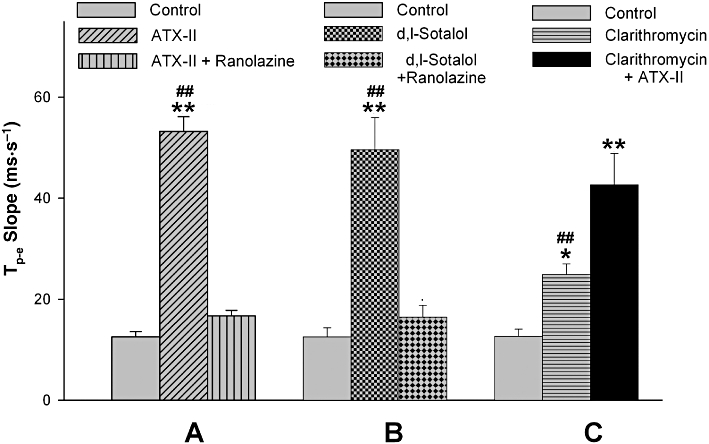

The reverse use-dependence of IKr: the effects of modulation of INa,L

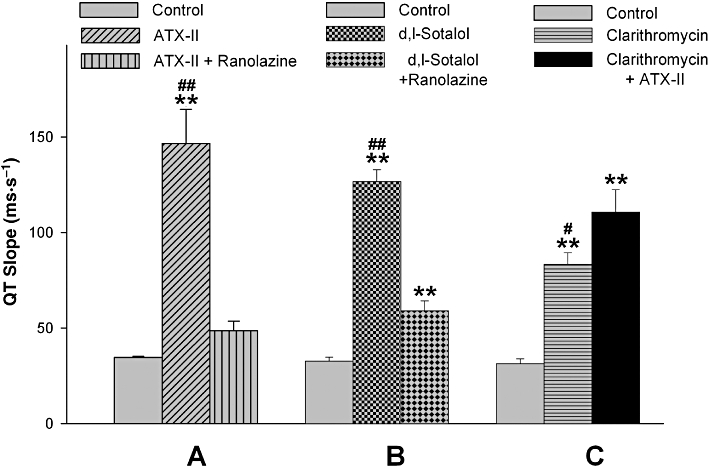

As shown in Figure 2, ATX-II, d,l-sotalol and clarithromycin caused more QT prolongation during slowing pacing rates, illustrating the reverse use-dependence. Interestingly, the reverse use-dependence related to Tp-e prolongation induced by these compounds appeared similar to that related to QT prolongation. ATX-II (30 nM), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) increased the QT-BCL slope (Figure 4). Similarly, the Tp-e-BCL slope was steeper in the presence of these compounds (Figure 5). Enhancement of INa,L by ATX-II increased both the QT-BCL and the Tp-e-BCL slopes, whereas inhibition of INa,L by ranolazine attenuated both of them (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

QT-BCL slopes (changes in QT interval as the function of basic cycle lengths), after infusion of ATX-II (30 nM) and ATX-II (30 nM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (A), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and d,l-sotalol (300 µM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (B), and clarithromycin (100 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) plus 1 nM ATX-II (C). **P < 0.01 compared with controls; #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 compared with the groups plus additional modulation of INa,L with ATX-II or ranolazine; one-way anova analysis.

Figure 5.

Tp-e-BCL slopes (changes in Tp-e interval as the function of basic cycle lengths), after infusion of ATX-II (30 nM) and ATX-II (30 nM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (A), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and d,l-sotalol (300 µM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (B), and clarithromycin (100 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) plus 1 nM ATX-II (C). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with controls; ##P < 0.01 compared with the groups plus additional modulation of INa,L with ATX-II or ranolazine; one-way anova analysis.

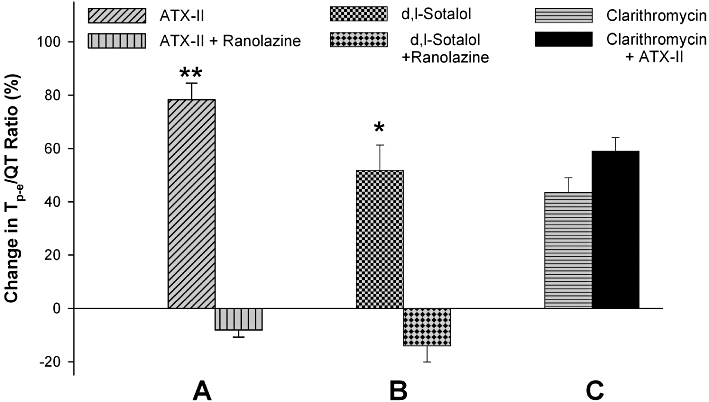

The Tp-e/QT ratio: the effects of modulation of INa,L

Previous studies have shown that the Tp-e interval represents dispersion of ventricular repolarization (Yan and Antzelevitch, 1998; 1999; Yan et al., 2001b; Patel et al., 2009). Its ratio to the QT interval (Tp-e/QT) has been shown to be an important arrhythmic index particularly related to the TdP risk of the QT prolonging agents (Liu et al., 2006; Gupta et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Therefore, the changes in the Tp-e/QT ratio by modulation of INa,L were also calculated. As shown in Figure 6, ATX-II (30 nM), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) all produced a marked increase in the Tp-e/QT ratio that could be attenuated by ranolazine or further enhanced by ATX-II.

Figure 6.

Changes in Tp-e/QT ratios after infusion of ATX-II (30 nM) and ATX-II (30 nM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (A), d,l-sotalol (300 µM) and d,l-sotalol (300 µM) plus 15 µM ranolazine (B), and clarithromycin (100 µM) and clarithromycin (100 µM) plus 1 nM ATX-II (C). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 when compared between two interventions within the same groups (Student's t-test).

As a result of these effects, reduction of INa,L by ranolazine significantly reduced the estimated TdP scores of ATX-II and d,l-sotalol. In contrast, ATX-II at a low dose (1 nM) significantly increased the TdP score of clarithromycin (Table 1). The proarrhythmic events related to TdP, before and after modulation of INa,L, is also shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Our results have provided novel insights into the role of INa,L in the pathogenesis of drug-induced TdP. Our principal findings are: (i) blockade of IKr or augmentation of INa,L by ATX-II exhibited significant reverse use-dependence, not only associated with the QT interval but also with the Tp-e interval, an index of TDR, in rabbit ventricular wedge preparations; (ii) enhancement of INa,L by ATX-II significantly amplified the reverse use-dependence of QT and Tp-e intervals and increased the arrhythmogenic potential of IKr blockers; and (iii) inhibition of INa,L by ranolazine reduced the reverse use-dependence of QT and Tp-e intervals and conferred significant antiarrhythmic effects.

The mammalian ventricular repolarization at steady state, represented by the QT interval on the surface ECG, is inversely proportional to heart rate (Carmeliet, 1977). In other words, tachycardia usually shortens ventricular repolarization and bradycardia prolongs it. The QT prolonging agents particularly with a pure IKr blockade property often amplify the physiological rate adaptation of ventricular repolarization, leading to reverse use-dependence. It is popularly believed that IKs, which can accumulate during tachycardia, is a major modulator for the reverse use-dependence of the IKr blockers (Jurkiewicz and Sanguinetti, 1993; Yang and Roden, 1996). However, evidence suggests that IKs may not be as important as we thought in modulation of the rate-dependence of cardiac APD. In the canine left ventricle, M cells exhibit a much steeper rate-APD slope than in the epicardial and endocardial cells, although the M cells have a much weaker IKs compared with the other two cell types (Liu and Antzelevitch, 1995). More directly, block of IKs by HMR 1556 was also associated with reverse use-dependent APD prolongation, that is, amplification of the intrinsic rate-dependent changes in APD (Stengl et al., 2003).

On the other hand, contribution of INa,L, an important inward current participating in maintaining the plateau of the action potential and contributing to a great extent to intrinsic heterogeneity of myocardium (Antzelevitch et al., 2004), has so far received relatively little attention in reverse use-dependence of QT/APD prolongation. Amongst three electrophysiologically distinct myocardial cell types spanning the ventricular wall, M cells have intrinsically larger INa,L and weaker IKs. Due to this, M cells have the longest duration of action potential and more prominent rate-dependent changes in QT/APD, contributing most importantly to TDR that manifests as Tp-e on the ECG (Antzelevitch et al., 1999; Yan et al., 2001b). Prominent TDR and reverse use-dependence in drug-induced TdP is well recognized now (Yan et al., 2001a; Hondeghem, 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Antzelevitch et al., 2007). In the rabbit left ventricle, cells with M cell characteristics occupy the entire Endo (Xu et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2001a,b;). Based on the findings of the present study, larger TDR during bradycardia may be the consequence of heterogeneous rate-dependent changes in APD at least partially due to heterogeneous distribution of INa,L across the ventricular wall. This is supported by the previous findings that blockade of the sodium current reduced TDR (Liu et al., 2006).

It is also interesting to note that potent blockade of INa,L by ranolazine outweighed the combined IKr blockade by sotalol and ranolazine itself in the reverse use-dependence of QT and Tp-e prolongation. Our finding that combinations of mild augmentation of INa,L and inhibition of IKr could have synergistic effect and could amplify the risk of drug-induced TdP, has clinical relevance and implications for drug development. Inhibition of INa,L could have potential therapeutic benefit especially in conditions with reduced repolarizing forces like left ventricular hypertrophy and long QT 3 (enhanced INa,L) and other pathological conditions (Nuyens et al., 2001; Maltsev and Undrovinas, 2008; Moss et al., 2008) or other forms of acquired long QT syndromes (reduced potassium currents) (Wu et al., 2006; 2008; Hale et al., 2008). In agreement with these basic research observations, Scirica et al. (2007) have recently demonstrated the antiarrhythmic efficacy of ranolazine in a clinical trial involving more than 6000 patients admitted for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

The ionic basis of our findings that INa,L contributes importantly to the reverse use-dependence of drug-induced QT and Tp-e prolongation is unknown. INa,L, unlike fast INa that inactivates in a few milliseconds and recovers fast, has very slow inactivation and recovery kinetics ranging from hundreds of milliseconds to minutes (Carmeliet, 1987; Undrovinas et al., 2002). Therefore, it is expected that INa,L is sensitive to changes in rates. The results of our work may raise interest in investigating the kinetics of INa,L and its changes in amplitude to different rates because inhibition of INa,L is useful in long QT 3 (Moss et al., 2008) and other pathological conditions with enhanced INa,L.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sharpe-Strumia Research Foundation and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81070162, 30870659 and 30971221).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APD

action potential duration

- ATX-II

Anemonia sulcata toxin

- BCL

basic cycle length

- EAD

early afterdepolarization

- Endo

endocardium

- IKr

rapidly activating delayed rectified K+ current

- IKs

slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current

- INa,F

fast sodium current

- INa,L

late sodium current

- TdP

torsades de pointes

- TDR

transmural dispersion of repolarization

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C. Arrhythmogenic mechanisms of QT prolonging drugs: is QT prolongation really the problem? J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl.):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Shimizu M, Yan GX, Sicouri S, Weissenburger J, Nesterenko VV, et al. The M cell: its contribution to the ECG and to normal and abnormal electrical function of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1124–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Fish JM, et al. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004;110:904–910. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Di Diego JM, Burashnikov A, Viskin S, Shimizu W, et al. Does Tpeak-Tend provide an index of transmural dispersion of repolarization? Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1114–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Repolarisation and frequency in cardiac cells. J Physiol (Paris) 1977;73:903–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E. Slow inactivation of the sodium current in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1987;408:18–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00581835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenichel RR, Malik M, Antzelevitch C, Sanguinetti M, Roden DM, Priori SG, et al. Drug-induced torsades de pointes and implications for drug development. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:475–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Young LH, Wu Y, Belardinelli L, Kowey PR, Yan GX. Increased late sodium current in left atrial myocytes of rabbits with left ventricular hypertrophy: its role in the genesis of atrial arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1375–H1381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01145.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Patel C, Patel H, Narayanaswamy S, Malhotra B, Green JT, et al. T(p-e)/QT ratio as an index of arrhythmogenesis. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41:567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gussak I, Litwin J, Morganroth J. Proarrhythmic potential of reverse use-dependent drugs. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40:432–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2007.03.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale SL, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L, Sweeney M, Kloner RA. Late sodium current inhibition as a new cardioprotective approach. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM. TRIad: foundation for proarrhythmia (triangulation, reverse use-dependence and instability) Novartis Found Symp. 2005;266:235–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Dimino T, Vohra Y, Cui C, Yan GX. Preclinical strategies to assess QT liability and torsadogenic potential of new drugs: the role of experimental models. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl.):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkiewicz NK, Sanguinetti MC. Rate-dependent prolongation of cardiac action potentials by a methanesulfonanilide class III antiarrhythmic agent. Specific block of rapidly active delayed rectifier K+ current by dofetilide. Circ Res. 1993;72:75–83. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DW, Antzelevitch C. Characteristics of the delayed rectifier current (IKr and IKs) in canine ventricular epicardial, midmyocardial and endocardial myocytes: a weaker IKs contributes to the longer action potential of the M cell. Circ Res. 1995;76:351–365. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Brown BS, Wu Y, Antzelevitch C, Kowey PR, Yan GX. Blinded Validation of the Isolated Arterially Perfused Rabbit Ventricular Wedge in Preclinical Assessment of Drug-Induced Proarrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:948–956. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltsev VA, Undrovinas A. Late sodium current in failing heart: friend or foe? Prog Biophys Molec Biol. 2008;96:421–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Schwarz KQ, Rosero S, Mcnitt S, Robinson JL. Ranolazine shortens repolarization in patients with sustained inward sodium current due to type-3 long-QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1289–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuyens D, Stengl M, Dugarmaa S, Rossenbacker T, Compernolle V, Rudy Y, et al. Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat Med. 2001;7:1021–1027. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel C, Burke JF, Patel H, Gupta P, Kowey PR, Antzelevitch C, et al. Is there a significant transmural gradient in repolarization time in the intact heart? Cellular basis of the T wave: a century of controversy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:80–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.791830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern WS, Carlsson L, Davis AS, Lynch WG, Mackenzie I, Palethorpe S, et al. Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:32–45. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00846-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1013–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salata JJ, Jurkiewicz NK, Wang J, Evans BE, Orme HT, Sanguinetti MC. A novel benzodiazepine that activates cardiac slow delayed rectifier K+ currents. Molec Pharmacol. 1998;54:220–230. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, Murphy SA, Belardinelli L, Hedgepeth CM, et al. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007;116:1647–1652. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengl M, Volders PG, Thomsen MB, Spatjens RL, Sipido KR, Vos MA. Accumulation of slowly activating delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs) in canine ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;551:777–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undrovinas AI, Maltsev VA, Kyle JW, Silverman N, Sabbah HN. Gating of the late Na+ channel in normal and failing human myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1477–1489. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Patel C, Cui C, Yan GX. Preclinical assessment of drug-induced proarrhythmias: role of the arterially perfused rabbit left ventricular wedge preparation. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Belardinelli L. An increase in late sodium current potentiates the proarrhythmic activities of low-risk QT-prolonging drugs in female rabbit hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:718–726. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Guo D, Li H, Hackett J, Yan GX, Jiao Z, et al. Role of late sodium current in modulating the proarrhythmic and antiarrhythmic effects of quinidine. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1726–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Rials SJ, Wu Y, Salata JJ, Liu T, Bharucha D, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy decreases slowly, but not rapidly activating delayed rectifier K+ currents of epicardial and endocardial myocytes in rabbits. Circulation. 2001;103:1585–1590. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the normal T wave and the electrocardiographic manifestations of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1998;98:1928–1936. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other Mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST Segment Elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan GX, Rials SJ, Wu Y, Liu T, Xu X, Marinchak Ra, et al. Ventricular hypertrophy amplifies transmural repolarization dispersion and induces early afterdepolarization. Am J Physiol. 2001a;281:H1968–H1975. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan GX, Wu Y, Liu T, Wang J, Marinchak RA, Kowey PR. Phase 2 early afterdepolarization as a trigger of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in acquired long-QT syndrome:Direct evidence from intracellular recordings in the intact left ventricular wall. Circulation. 2001b;103:2851–2856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Roden DM. Extracellular potassium modulation of drug block of IKr. Implications for torsade de pointes and reverse use-dependence. Circulation. 1996;93:407–411. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt AC, Eddlestone GT, Thomas GP, Nesterenko VV, Antzelevitch C. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H689–H697. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]