Abstract

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance induced by acute injuries or critical illness are associated with increased mortality and morbidity, as well as later development of type 2 diabetes. The molecular mechanisms underlying the acute onset of insulin resistance following critical illness remain poorly understood. In the present studies, the roles of serine kinases, inhibitory κB kinase (IKK) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), in the acute development of hepatic insulin resistance were investigated. In our animal model of critical illness diabetes, activation of hepatic IKK and JNK was observed as early as 15 min, concomitant with the rapid impairment of hepatic insulin signaling and increased serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1. Inhibition of IKKα or IKKβ, or both, by adenovirus vector-mediated expression of dominant-negative IKKα or IKKβ in liver partially restored insulin signaling. Similarly, inhibition of JNK1 kinase by expression of dominant-negative JNK1 also resulted in improved hepatic insulin signaling, indicating that IKK and JNK1 kinases contribute to critical illness-induced insulin resistance in liver.

Keywords: serine kinase, insulin signaling, liver, injury

insulin resistance is involved in the pathogenesis of a number of chronic metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, and develops over months, years, or decades. However, insulin resistance can also occur extremely rapidly after injuries, infection, or critical illnesses and is referred to as “diabetes of injury” or, more inclusively, “critical illness diabetes” (3, 8, 29, 44, 46, 47). Critical illness diabetes-induced acute insulin resistance results in elevated blood glucose due to enhanced hepatic glucose production and/or impaired peripheral glucose uptake (29, 44, 46). This acute development of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance predisposes critically ill patients to detrimental outcomes and increased mortality (6, 14, 22, 45, 53). In addition, much like gestational diabetes, recent clinical studies suggest that the acute development of critical illness diabetes after surgery and the concomitant hyperglycemia are strongly correlated with the later development of type 2 diabetes (10). The molecular mechanisms underlying the development of this acute insulin resistance in critical illness diabetes remain poorly understood. Insights into the pathogenesis of acute insulin resistance may provide novel and specific therapeutic strategies for improving recovery and survival of critically ill patients and may suggest interventions for the greater likelihood of later development of type 2 diabetes.

Insulin is a major hormone regulating glucose homeostasis through suppression of glucose production in liver and promotion of glucose disposal in muscle and adipose tissue (38, 41). Insulin binds to the insulin receptor (IR) on the surface of target cells, resulting in IR autophosphorylation (39, 41). Activated IR recruits and phosphorylates IR substrate (IRS) proteins at multiple tyrosine residues, which in turn bind to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and activate the kinase Akt and its downstream targets, regulating glucose metabolism (39, 41). Injuries or critical illness is associated with increased intracellular stress and activation of inflammatory pathways (17, 20, 44, 50). Possible contributors to the insulin resistance of critical illness diabetes are serine kinases, such as inhibitory κB kinase (IKK)-β and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), which share the ability to directly induce serine phosphorylation of IRS1, decrease insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS1, and inhibit insulin action (13, 16, 55, 58, 59).

The IKK complex is central to the inflammatory NF-κB pathway (15) and consists of two catalytic subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, and a regulatory subunit, Nemo. Overexpression of the active form of IKKβ in hepatocytes eventually leads to insulin resistance in liver and skeletal muscle (7). Deletion or inhibition of IKKβ in liver (5, 7, 13), but not in skeletal muscle (37), attenuates obesity-related chronic insulin resistance. In addition, Nemo is suggested to be necessary in formation of a IKK-IRS1 complex in TNFα-induced insulin resistance (34).

The JNK kinase may also regulate insulin resistance. Total JNK activity is elevated in dietary and genetic (ob/ob) models of obesity, and absence of JNK1 results in improved insulin sensitivity and decreased adiposity in obese mice (16). Suppression of the JNK pathway in liver improves insulin resistance and decreases blood glucose level in genetic models of severely obese (db/db) mice (35). However, nothing is known about the contribution of the IKK and JNK1 kinase pathways to development of the acute insulin resistance that develops in critical illness diabetes. Unlike high-fat diet or genetic models of obesity or type 2 diabetes, which are chronic problems that take many weeks, months, years, or decades to develop, critical illness diabetes develops very rapidly after an injury or infection. There is no a priori reason to believe that critical illness diabetes will have the same or different mechanisms of development. Since it can develop in our animal model of critical illness diabetes within minutes after hemorrhage (23, 24, 27, 28, 43, 52), the mechanisms of development may be very different from those associated with chronic forms of insulin resistance.

In the present studies, we found that hepatic IKK and JNK were activated within minutes after trauma and hemorrhage, with a time course similar to the rapid impairment of hepatic insulin signaling and increased serine phosphorylation of IRS1. Inhibition of IKK and/or JNK1 kinases in liver improved hepatic insulin signaling and attenuated the hemorrhage-induced increase in IRS1 serine phosphorylation. The present studies suggest that JNK1 and IKK kinases contribute to the acute development of insulin resistance in critical illness diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model of trauma and hemorrhage.

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals, and the experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g body wt; Harlan) were housed in animal facilities for ≥1 wk before experiments. Surgical trauma and hemorrhage were performed as described previously (24, 27, 28, 52). Rats were fasted for 18–20 h before the experiment. Rats were anesthetized by inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane, and a 5-cm midline laparotomy was performed. Polyethylene (PE-50) catheters were placed in both femoral arteries and the right femoral vein for bleeding, monitoring of blood pressure, and resuscitation, respectively. Rats were bled rapidly to reach a mean arterial pressure of 35–40 mmHg within 10 min and maintained for 15 min (TH15′), 30 min (TH30′), 60 min (TH60′), or 90 min (TH90′). The trauma-alone (T) groups were subjected to anesthesia and surgical procedures described for the trauma-and-hemorrhage groups but were not hemorrhaged. In all groups of rats, 5 U of insulin in saline or saline alone was injected into the hepatic portal vein, and tissues were harvested 1 min after injection and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. This high dose of insulin ensures the maximal possible induction, even if the liver is insulin-resistant, and ensures sufficient delivery to the liver during hemorrhage.

Recombinant adenoviral vectors.

The recombinant adenoviral (Ad) vectors expressing a dominant-negative (DN) mutant (K44M) of IKKα (Ad-DN-HA-IKKα) (9, 56), a DN mutant (K44A) of IKKβ (Ad-DN-HA-IKKβ) (9, 56), and the control Ad vector expressing β-galactosidase (Ad5-nt-LacZ) were purchased from the University of Iowa Vector Core (9). The two IKK mutants were rendered incapable of binding ATP and, thus, lost functional kinase capability. The Ad vector expressing a DN mutant (T183A/Y185F) of JNK1 (Ad-DN-JNK1) was purchased from Cell Biolabs (catalog no. ADV-115) and was rendered kinase-dead by these two mutations within the JNK kinase domain. The Ad vectors were amplified in 293A cells and purified twice by cesium chloride gradient ultracentrifugation followed by dialysis. The biological titer [plaque-forming units (pfu)/ml] was determined by the TCID50 (tissue culture infectious dose 50) method (AdenoVactor Vector System) based on the development of a cytopathic effect in 293 cells. Replication-competent Ad contamination was not detected in purified virus stocks as screened by PCR with the primers flanking the E1 region.

Administration of Ad vectors in vivo.

Rats were injected with the purified Ad vectors (1010 pfu/rat) via the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, the animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage for 60 min (TH60′), and tissues were harvested for analysis of insulin signaling and kinase activity.

Western blot analysis.

Liver tissues from each animal were homogenized in lysis buffer as described previously (24, 28). The tissue lysates were centrifuged, and the supernatants were stored at −80°C. The concentrations of the protein lysates were assayed by bicinchoninic acid assay as described in the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and the lysates (30 μg/lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were immunoblotted with anti-Tyr972-phosphorylated IR, anti-Thr183/Tyr185-phosphorylated JNK1/2, and anti-Ser312-phosphorylated IRS1 (S307 rat, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-total IR and anti-JNK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-pan-actin, anti-total ERK, anti-Ser473 phosphorylated Akt, anti-total Akt, anti-Ser180/Ser181-phosphorylated IKKα/β, anti-IKKα, and anti-IKKβ (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) antibodies.

Gel-shift assay.

Nuclear proteins were extracted from frozen liver samples according to the manufacturer's instruction (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were measured by bicinchoninic acid protein assay. Oligonucleotides containing the κB consensus sequence (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) were labeled with [32P]CTP using Klenow DNA polymerase. The binding reaction was performed as described previously (26). Briefly, nuclear protein (10 μg) was incubated with labeled oligonucleotide probe for 30 min on ice and separated on 4–20% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine-EDTA gels. Excess of a specific unlabeled competitor sequence was used to out-compete the specific interactions to indicate specific binding.

Immunohistochemistry.

The liver tissues were rinsed in PBS and embedded in HistoPrep frozen tissue embedding medium (Fisher Scientific) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen livers were cryosectioned (10 μm) and subjected to immunohistochemical staining with anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). The liver sections were fixed in 70% ethanol overnight and blocked with 0.1% sodium azide and 0.5% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min. Overnight incubation with the primary antibody (anti-HA, 1:200 dilution in 1% BSA) was followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and detected using diaminobenzidine substrate. The sections were counterstained briefly with hematoxylin, and images were obtained using a Leica microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Densitometric and statistical analysis.

Enhanced chemiluminescence images of immunoblots were scanned using a flatbed scanner (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) and quantified using Zero D-Scan (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA). Data are presented as means ± SE. The statistical differences were analyzed by ANOVA for comparison among multiple groups or Student's t-test for comparison between two groups. P ≥ 0.05 was considered not statistically significant different.

RESULTS

Activation of IKK/NF-κB pathway in liver following trauma and hemorrhage.

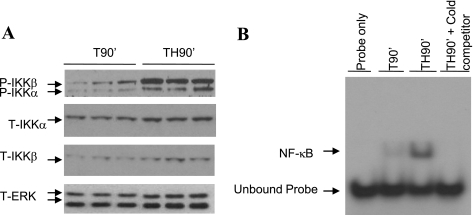

Critical illnesses and injuries, including hemorrhagic shock, can initiate acute inflammatory responses characterized by increased production of inflammatory factors and activation of inflammatory pathways such as the IKK/NF-κB pathway (4, 49). Activation of the IKK complex depends on the phosphorylation sites within the activation loop of the kinase (15). To determine whether IKK kinases are activated in liver following trauma and hemorrhage, phosphorylation of IKK kinases was examined with an antibody specific for Ser181-phosphorylated IKKβ and Ser180-phosphorylated IKKα. Increased phosphorylation/activation of IKKβ and IKKα was detected after TH90′ compared with T90′ (Fig. 1A). When measured, total IKKα and total IKKβ levels were not altered by trauma and hemorrhage (Fig. 1A) at the times that phosphorylated IKKβ and phosphorylated IKKα were induced.

Fig. 1.

Activation of the inhibitory κB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB pathway in liver after trauma and hemorrhage. A: rats were subjected to 90 min of trauma and hemorrhage (TH90′) or trauma alone (T90′), and liver tissues were harvested. Western blot analysis was performed on liver lysates exposed to anti-Ser181-phosphorylated IKKβ (P-IKKβ)/Ser180-phosphorylated IKKα (P-IKKα), total IKKα (T-IKKα), total IKKβ (T-IKKβ), and total ERK (T-ERK) antibodies; the level of total ERK was probed as a loading control. B: representative EMSA. Liver nuclear proteins from TH90′ and T90′ rats were analyzed by gel-shift assay with a 22-nt radiolabeled probe of NF-κB consensus sequence. Cold: 20× unlabeled competitor. Assay represents results from several repeated experiments.

NF-κB, a downstream target of the IKK complex, is an important transcription factor regulating expression of inflammatory factors (15). Activation of NF-κB in liver after trauma and hemorrhage was examined by gel-shift assay with a radiolabeled NF-κB consensus sequence probe, and DNA binding activity of NF-κB was significantly higher at TH90′ than T90′ (representative blot, Fig. 1B). These studies indicate an activation of the IKK/NF-κB pathway in response to hemorrhage. In additional experiments, there was a slight increase in DNA binding activity of NF-κB in trauma-only animals compared with normal (no trauma or hemorrhage) animals. This suggests a minor activation of this pathway by trauma alone and agrees with our previous work indicating a mild level of insulin resistance following trauma alone (28).

Time course of IKK and JNK activation.

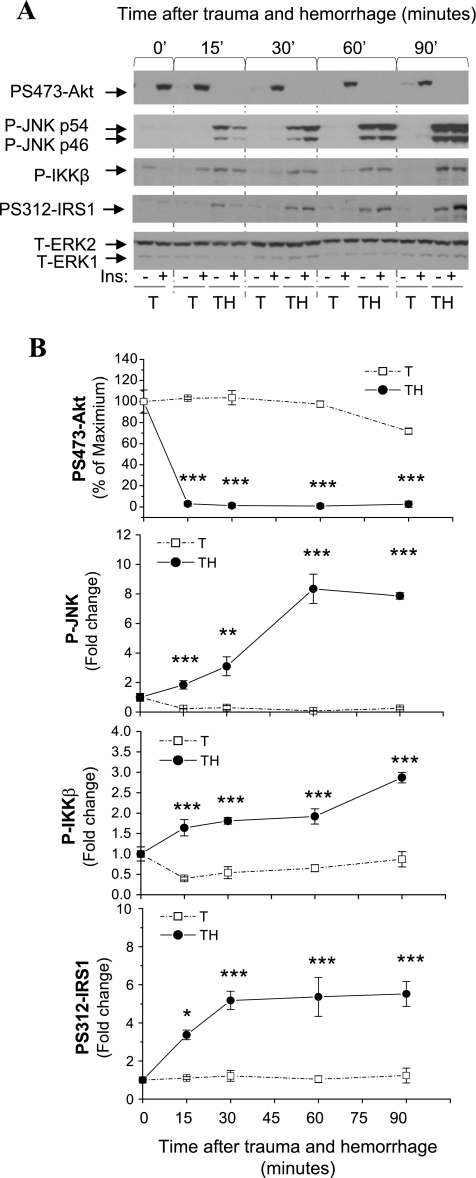

We have found that hepatic insulin resistance developed at TH15′, as indicated by severely decreased insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 2) (24). In parallel experiments, the time course of IKKβ, JNK1, and phosphorylation of IRS1 at Ser312 in liver following trauma and hemorrhage was examined. Significantly elevated phosphorylated IKKβ, phosphorylated JNK1, and Ser312-phosphorylated IRS1 were observed at TH15′ compared with trauma-alone groups, with levels continuing to increase through ≥90 min (Fig. 2). We demonstrated previously that the total levels of Akt, JNK, and IRS1 are not affected by trauma and hemorrhage (28, 52). The induction of IKKβ, JNK1, and Ser312 IRS1 phosphorylation presented here are not dependent on the administration of insulin but are due to hemorrhage. This early activation of IKKβ, JNK1, and Ser312 IRS1 phosphorylation may allow them to play a role in the rapid development of insulin resistance in liver following trauma and hemorrhage.

Fig. 2.

Time course of Akt, JNK1, IKKβ, and Ser312 insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) phosphorylation following trauma and hemorrhage. Rats were subjected to trauma and hemorrhage (TH) or trauma alone (T), and tissues were harvested at 15, 30, 60, and 90 min. A: Western blot analysis of liver protein extracts exposed to anti-Ser473-phosphorylated Akt (PS473-Akt), Thr181/Tyr183-phosphorylated JNK1/2 (P-JNK), Ser181-phosphorylated IKKβ/Ser180-phosphorylated IKKα, Ser312-phosphorylated IRS1 (PS312-IRS1), and total ERK antibodies. B: time course of Akt, JNK1, IKKβ, and Ser312 IRS1 phosphorylation after trauma and hemorrhage and trauma alone. Values are means ± SE (n = 6 for each group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. T at the corresponding time point.

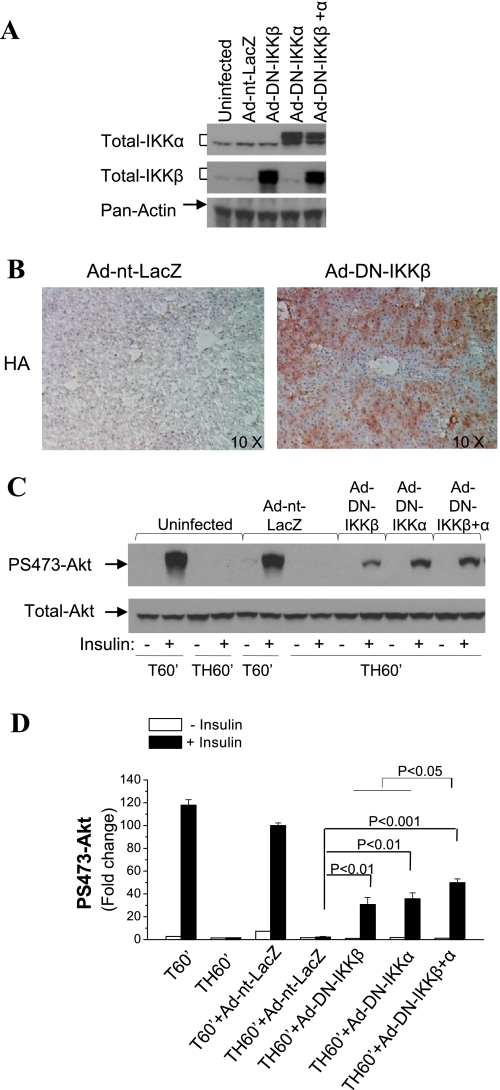

Inhibition of IKK kinases resulted in improved hepatic insulin signaling.

To directly investigate the role of IKKβ in hepatic insulin signaling following trauma and hemorrhage, rats were injected with Ad vectors expressing DN IKKβ (Ad-DN-IKKβ, 1010 pfu) via the tail vein. Since IKKα, also a serine kinase, exists in the complex interacting with IRS1 (13), it may also contribute to IRS1 serine phosphorylation and participate in insulin resistance. We therefore included two other groups: a group injected with Ad-DN-IKKα (1010 pfu) and a group injected with Ad-DN-IKKβ (5 × 109 pfu) + Ad-DN-IKKα (5 × 109 pfu). At 4 days postinjection, the animals were subjected to TH60′ and injected with insulin or saline immediately before tissue was harvested. Expression of DN IKK kinases in liver in all rats was confirmed by Western blot analysis with total IKKα- or IKKβ-specific antibodies, which recognize endogenous IKK kinases and the DN mutants of the IKK kinases. The expression of endogenous IKKα or IKKβ was not affected by the control Ad vector Ad-nt-LacZ (Fig. 3A) or by injection of the DN of the other IKK kinase, whereas expression of DN IKKα, IKKβ, or both, was achieved by their injection. Immunohistological examination indicated that a significant number, but not all, of the liver cells expressed the HA-tagged DN constructs (IKKβ, a representative liver section shown in Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effects of IKK kinase inhibition on hepatic insulin signaling after trauma and hemorrhage. Rats were injected with adenovirus (Ad) vectors expressing dominant-negative (DN) mutant of IKKα [Ad-DN-IKKα; 1010 plaque-forming units (pfu)] or IKKβ (Ad-DN-IKKβ; 1010 pfu), control Ad vector (Ad-nt-LacZ; 1010 pfu), or Ad-DN-IKKα (5 × 109 pfu) + Ad-DN-IKKβ (5 × 109 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage, and tissues were harvested. A: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to total IKKα-, total IKKβ-, and pan-actin-specific antibodies. B: immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen liver sections exposed to anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody. Magnification ×10. C: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to Ser473-phosphorylated Akt and total Akt antibodies. D: fold change in Ser473-phosphorylated Akt. Values are means ± SE (n = 3–4 rats/group).

As expected, in the trauma-alone uninfected and the Ad-nt-LacZ-infected groups (T60′), insulin stimulated hepatic Ser473 Akt phosphorylation. However, induction of phosphorylated Akt was almost completely abolished after TH60′ (Fig. 3, C and D). Expression of DN IKKβ in liver increased insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation following trauma and hemorrhage compared with the uninfected and the Ad-nt-LacZ control rats (Fig. 3, C and D). Significant improvements in insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation following trauma and hemorrhage were also detected following expression of DN IKKα. In addition, there was a significantly greater improvement in animals following administration of DN IKKα and IKKβ (Fig. 3, C and D). These results suggest that IKKα and IKKβ contribute to hemorrhage-induced defects in insulin signaling. However, for all groups, insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation was still lower following trauma and hemorrhage than following trauma alone, indicating only a partial recovery of insulin signaling by Ad vector-mediated expression of DN mutant IKK kinases.

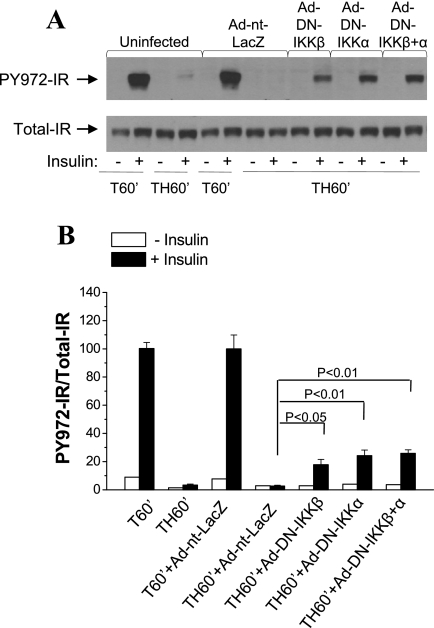

Next, insulin signaling upstream of Akt was examined. Tyr972 of the IR serves as binding site for IRS1 (54). Insulin-induced Tyr972 IR phosphorylation was impaired following trauma and hemorrhage in the uninfected and Ad-nt-LacZ control rats (Fig. 4A). Expression of DN IKKβ, DN IKKα, or both, resulted in increased Tyr972 IR phosphorylation in liver compared with uninfected and Ad-nt-LacZ control groups (Fig. 4). These results suggest that hemorrhage-induced defects in hepatic insulin signaling occur at the level of the IR, and IKK kinases may inhibit insulin signaling through decreasing IR tyrosine phosphorylation upstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Effects of IKK kinase inhibition on insulin-induced insulin receptor (IR) phosphorylation after trauma and hemorrhage. Rats were injected with Ad-DN-IKKα (1010 pfu), Ad-DN-IKKβ (1010 pfu), Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu), or Ad-DN-IKKα (5 × 109 pfu) + Ad-DN-IKKβ (5 × 109 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage, and liver tissues were harvested. A: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to Tyr972-phosphorylated IR (PY972-IR) and total IR antibodies. B: ratio of Tyr972-phosphorylated to total IR. Values are means ± SE (n = 3–4 rats/group).

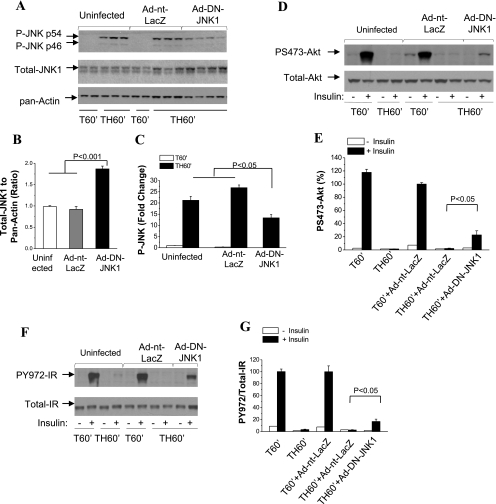

Inhibition of JNK1 improved hepatic insulin signaling.

To directly investigate the role of JNK1 kinase in the acute development of hemorrhage-induced hepatic insulin resistance, rats were injected with Ad vector expressing DN JNK1. At 4 days postinjection, the animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage. Expression of DN-JNK1 was determined using a total JNK1-specific antibody. Total JNK1 increased consistently and significantly following administration of Ad-DN-JNK1 (Fig. 5, A and B). In the same animals, JNK1 phosphorylation was decreased by 50% following administration of Ad-DN-JNK1 (Fig. 5, A and C). Inhibition of JNK1 by Ad-DN-JNK1 also resulted in increased insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5, D and E), as well as Tyr972 phosphorylation of IR after trauma and hemorrhage (Fig. 5, F and G), indicating a potential role of JNK1 kinase in hemorrhage-induced insulin resistance.

Fig. 5.

Effects of JNK1 kinase inhibition on hepatic insulin signaling after trauma and hemorrhage. Rats were injected with Ad-DN-JNK1 (1010 pfu) or Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage for 60 min, and liver tissues were harvested. A–C: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to Thr181/Tyr183-phosphorylated JNK1/2-, total JNK1-, and pan-actin-specific antibodies. D and E: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to Ser473-phosphorylated Akt and total Akt antibodies. F and G: Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to Tyr972-phosphorylated IR and total IR antibodies. Values in B, C, E, and G are means ± SE (n = 3–4 rats/group).

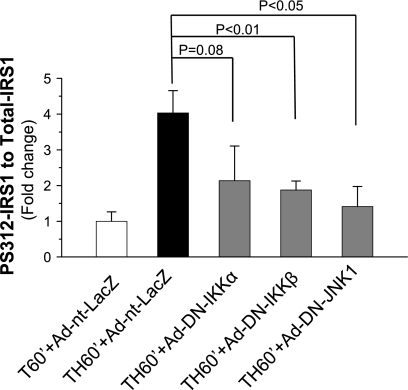

Inhibition of IKKα, IKKβ, or JNK1 results in decreased IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation.

JNK1 and IKKβ have been shown to associate with IRS1 and phosphorylate IRS1 at Ser312 in vitro (1, 13), which impairs IR (18) or IRS1 tyrosine phosphorylation (2). The effect of the DN IKKs or DN JNK1 expression on the hemorrhage-induced increase of IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation was determined. The level of IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation increased following trauma and hemorrhage, and administration of Ad-nt-LacZ was ineffective in altering this increase. However, Ser312 IRS1 phosphorylation decreased significantly following inhibition of JNK1 or IKKβ (Fig. 6) and approached significance following inhibition of IKKα (P = 0.08). This suggests that, after acute hemorrhage, activation of JNK1 and IKKβ, and possibly IKKα, contributes to the increased phosphorylation of IRS1 on Ser312 in the liver of rats, which may then inhibit insulin signaling.

Fig. 6.

IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation after inhibition of IKKs or JNK1. Rats were injected with Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu), Ad-DN-IKKα (1010 pfu), Ad-DN-IKKβ (1010 pfu), or Ad-DN-JNK1 (1010 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage for 60 min, and liver tissues were harvested. Western blot analysis was performed on liver lysates exposed to Ser312-phosphorylated IRS1- and total IRS1-specific antibodies. Values are means ± SE (n = 3–4 rats/group).

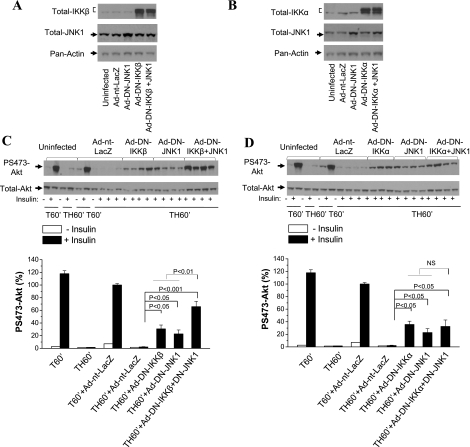

Inhibition of JNK1 and IKKβ, not JNK1 and IKKα, resulted in an additive effect on hepatic insulin signaling.

The effects of inhibition of either IKK kinase in combination with inhibition of JNK1 kinase on acute hepatic insulin resistance were then determined. Rats were coinjected with Ad-DN-IKKβ or Ad-DN-IKKα and Ad-DN-JNK1. Expression of DN-IKKβ or DN-IKKα in the liver of coinjected groups was confirmed by Western blot analysis with total IKKβ (Fig. 7A) or total IKKα (Fig. 7B). Expression of DN IKKβ and DN JNK1 simultaneously in liver significantly increased insulin-induced Ser473 Akt phosphorylation following trauma and hemorrhage, which was greater than the effect of either DN IKKβ or DN JNK1 alone (Fig. 7C). In contrast, insulin-induced Ser473 Akt phosphorylation after trauma and hemorrhage in the group injected with Ad-DN-IKKα + Ad-DN-JNK1 was not different from that in groups injected with Ad-DN-IKKα or Ad-DN-JNK1 alone (Fig. 7D). This suggests that IKKα and IKKβ may act differently, and IKKα and JNK kinases may act in series, in inducing hepatic insulin resistance following trauma and hemorrhage, resulting in no additive effect. IKKβ may function in parallel with JNK1, allowing for an additive effect when both are inhibited.

Fig. 7.

Effects of inhibition of either IKKβ or IKKα and JNK1 kinases on hepatic insulin signaling after trauma and hemorrhage. Rats were injected with Ad-DN-IKKα (1010 pfu), Ad-DN-IKKβ (1010 pfu), or Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu) or coinjected with Ad-DN-IKKα (5 × 109 pfu) or Ad-DN-IKKβ (5 × 109 pfu) with Ad-DN-JNK1 (5 × 109 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage, and liver tissues were harvested. A and B: representative Western blot analysis of liver lysates exposed to total IKKβ-, total IKKα-, total JNK1-, and pan-actin-specific antibodies. C and D: representative Western blots of liver lysates exposed to Ser473-phosphorylated Akt and total Akt antibodies. Values are means ± SE (n = 3–4 rats/group).

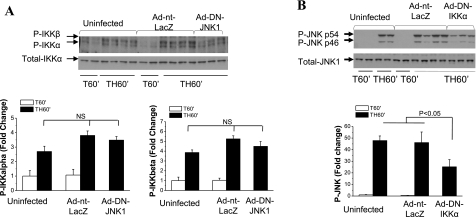

Cross talk between IKK and JNK kinases.

To determine the cross talk between IKK and JNK kinases, effects of IKK or JNK inhibition on activation of the other kinase were examined. JNK1 inhibition did not alter the phosphorylation of IKKα or IKKβ (Fig. 8A), whereas expression of DN IKKα in liver resulted in a significant decrease in JNK1 phosphorylation/activation after trauma and hemorrhage (Fig. 8B). Unlike DN IKKα, there is no significant decrease of JNK phosphorylation after expression of DN IKKβ (data not shown). This suggests that IKKα may act upstream of JNK kinase following trauma and hemorrhage.

Fig. 8.

Cross talk between IKK and JNK kinases. A: rats were injected with Ad-DN-JNK1 (1010 pfu) or Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage for 60 min, and liver tissues were harvested. Western blot analysis was performed on liver lysates exposed to Ser180-phosphorylated IKKα/Ser181-phosphorylated IKKβ- and total Akt-specific antibodies. Values are means ± SE (n = 4–5 rats/group). B: rats were injected with Ad-DN-IKKα (1010 pfu) or Ad-nt-LacZ (1010 pfu) through the tail vein. At 4 days postinjection, animals were subjected to surgical trauma and hemorrhage for 60 min, and liver tissues were harvested. Western blot analysis was performed on liver lysates exposed to Thr181/Tyr183-phosphorylated JNK1/2 and total JNK1 antibodies. Values are means ± SE (n = 4–5 rats/group).

DISCUSSION

Critical illness diabetes, as evidenced by elevated blood glucose, is common in patients with injuries or critical illness due to increased hepatic glucose production and/or impaired peripheral glucose uptake, independent of previous diabetic status (29, 44, 46). The development of critical illness diabetes and its hyperglycemia in patients after acute injuries is of clinical concern because of the occurrence of adverse outcomes (6, 14, 22, 53). However, deleterious effects can also occur if the hyperglycemia is treated too aggressively by insulin, with increased hypoglycemic incidents (12). To delineate the mechanisms underlying the acute onset of insulin resistance after injuries, we have established an experimental rat model of critical illness diabetes. Our previous studies demonstrate a rapid development of insulin resistance in liver (23, 24, 27, 52). In the present studies, the rapid activation of JNK and another signaling pathway, the IKK/NF-κB pathway, was established. The causative roles of the IKK and JNK kinases in the acute development of insulin resistance were determined by direct inhibition of the IKK and JNK1 kinases with the Ad-mediated expression of DN mutants of IKKs and JNK1 in liver.

The response to injury/hemorrhage involves a complex coordination of the immune, cardiovascular, endocrine, and nervous systems (20), resulting in increased cellular stresses. These include (but are not limited to) oxidative stress and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, which can then induce the activation of the JNK and IKK/NF-κB pathways (31). In the present studies, the time courses of IKK/NF-κB and JNK activation were examined and found to increase as early as 15 min and continued to increase in liver through the 90-min hemorrhage period. Thus activation of the JNK and IKK/NF-κB pathways may represent early and rapid signaling events in liver following injury/hemorrhage. Activation of IKK/NF-κB and JNK continued to increase and was maintained throughout the 90-min hemorrhage period, as was the defect in insulin signaling. In separate studies (57), we found that hemorrhage induces a rapid increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in liver, and inhibition of the increase of ROS significantly decreased the acute development of hepatic insulin resistance. The data to date imply that the rapid activation of JNK and IKKs may be caused by the increase of ROS levels during hemorrhage.

Numerous studies have indicated the important role of IKKβ and JNK1 kinases in chronic insulin resistance in response to high-fat diet or obesity (5, 7, 13, 16, 35). However, the role of acute activation of IKK and JNK kinases in the rapid development of insulin resistance is not known. Unlike high-fat diet-induced obesity or type 2 diabetes, which are chronic problems that take many weeks, months, years, or decades to develop, the development of critical illness diabetes occurs very rapidly after an injury or infection. There is no a priori reason to believe that critical illness diabetes will have the same or different mechanisms of development. Since the mechanisms of development are unknown and critical illness diabetes is clearly an important clinical problem, the mechanisms need to be explored. In the present studies, DN IKKβ, IKKα, or JNK1 expression significantly improved insulin signaling, suggesting that the early activation of the IKK and JNK kinases contributes to the rapid onset of insulin resistance in critical illness diabetes. Injection of Ad-DN-IKKβ + Ad-DN-JNK1 resulted in additive effects on insulin sensitivity, further confirming that both contribute to the development of insulin resistance and may act in parallel. A partial causative factor in the acute development of hepatic insulin resistance within critical illness diabetes may be the activation of the IKK and JNK signaling pathway within minutes of hemorrhage.

However, defects in hepatic insulin signaling were only partially recovered by Ad-mediated expression of DN IKKs or DN JNK1, or both. The immunohistochemical staining of liver sections indicated that a large number of liver cells, but certainly not all hepatocytes, expressed DN proteins delivered by the Ad vectors. Since the DN protein works intracellularly, only those cells infected and expressing sufficient quantities of the DN protein will be affected. This may, in part, account for the partial blockade of the development of insulin resistance (partial increase of insulin signaling) after DN IKK and DN JNK1 expression. In addition, the Ad vector itself can initiate host inflammatory responses (19) and activate the JNK and IKK pathways (30, 33, 42), which may inhibit the activity of the DN IKK and JNK1 kinases and lower their effectiveness in blocking the development of insulin resistance in liver. Moreover, critical illness diabetes is complex, and we assume that there are multiple other causative factors and, therefore, potentially other signaling pathways, in addition to the IKK and JNK kinases, such as mammalian target of rapamycin and p38, which are likely involved in inducing the full insulin-resistant state. These other contributors remain to be determined in future studies on the development of acute insulin resistance in critical illness diabetes.

Among the three major subunits of the IKK complex, IKKβ is most clearly involved in the development of the chronic insulin-resistant state (5, 7, 13), with Nemo also necessary for TNFα-induced insulin resistance (34), whereas the role of IKKα in insulin resistance has not been as well studied. IKKα and IKKβ are catalytic subunits of the IKK complex and share extensive structural homology (36). IKKα and IKKβ contribute to inhibitory-κB phosphorylation and activation of NF-κB, and their similar abilities suggest that their functions are likely to be redundant and overlapping (36). In addition to forming heterodimers with IKKβ, IKKα can also form a homodimer, which may play a distinct role (36). Our data indicate an additive effect of expression of both DN constructs (DN IKKβ and DN IKKα), suggesting that they may also have separate actions in the development of acute insulin resistance in our animal model. Since IKKα exists in a complex that interacts with IRS1 (13), IKKα may also participate in inhibiting insulin signaling. Inhibition of IKKα by Ad-mediated expression of a DN mutant was found to improve hepatic insulin sensitivity in our model of critical illness diabetes. Thus, unlike chronic forms of insulin resistance, IKKα also likely contributes to acute insulin resistance that develops in critical illness diabetes.

There was an additive effect of expression of the DN forms of IKKβ and JNK1, suggesting that they act separately, potentially in parallel pathways, to cause acute insulin resistance. However, unlike IKKβ, no additive effect was detected following expression of DN IKKα and JNK1, suggesting that IKKα may act in series with JNK kinase in inhibiting hepatic insulin signaling in our model of critical illness diabetes. Further experiments demonstrated that inhibition of JNK kinase had no effect on IKKα or IKKβ activation, whereas expression of DN IKKα in liver resulted in decreased JNK1 activation. Together, these data suggest that IKKα acts upstream of JNK kinase in inducing hepatic insulin resistance. Thus, after activation of IKKα, IKKα can activate JNK kinase. In combination with other possible activators of JNK kinase and activation of a separate pathway containing activated IKKβ, there is a significant reduction of insulin signaling in our experimental model of critical illness diabetes.

Several studies have demonstrated cross talk between the IKK and JNK pathways, and IKK can act as a positive or negative regulator of JNK activation, depending on the type of stress (25, 40, 51). Phosphorylation of JNK is induced by a series of serine kinases, including MEKK1, MKK4, and MKK7. Thus, IKKα, a serine kinase, could phosphorylate/activate an intermediate protein that is important for JNK activation. Another possibility is that alterations in the activity of IKKα, an important kinase for canonical and noncanonical NF-κB activation, could result in altered expression of a number of genes, such as PKC, leading to activation of JNK. However, this is unlikely in our animal model of critical illness, since activation of the IKK and JNK pathways occurs so rapidly. Thus the exact mechanisms of how IKKα is involved in hemorrhage-induced JNK activation remain to be determined.

A common feature of the IKK and JNK1 kinases is their ability to directly bind to and phosphorylate IRS1 at Ser312, which may inhibit insulin signal transduction (13, 16, 55, 58, 59). Increased IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation was observed in liver following the development of critical illness diabetes, and inhibition of JNK1 or IKKs resulted in decreased phosphorylated (Ser312) IRS1, suggesting that IRS1 could be a target molecule for active IKK and JNK kinases. However, an acute defect in insulin signaling after injury/hemorrhage was also detected at the IR, upstream of IRS1, and inhibition of IKK or JNK signaling improved insulin-induced IR tyrosine phosphorylation. A possible explanation is provided by Hotamisligil and colleagues (18), who found that serine phosphorylation of IRS1 allows IRS1 to inhibit insulin-induced IR tyrosine autophosphorylation. Thus, increased hepatic IRS1 Ser312 phosphorylation could decrease insulin-induced IR activation. In addition, although much less extensively studied, serine phosphorylation of the IR may also be an important mechanism for the development of insulin resistance, which could result in decreased activation of the insulin signaling pathway (32). Thus, activation of serine kinases in the acute development of critical illness diabetes could result in serine phosphorylation of the IR, leading to hemorrhage-induced hepatic insulin resistance. This possibility needs to be studied further, but no candidate serines of the IR have been identified.

In summary, we demonstrate that activation of the JNK and IKK/NF-κB pathways occurs early in the development of critical illness diabetes. The JNK1 and IKK kinases contribute to the acute development of critical illness diabetes-associated hepatic insulin resistance. Intensive insulin therapy has proven to be beneficial (47). However, there is some debate as to blood glucose target and, therefore, the intensity of insulin treatment that is most beneficial (11, 12, 21, 48). Our current studies suggest IKKs or JNK inhibitors as potential, novel therapeutic agents for treating or preventing the development of insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in critically ill patients.

GRANTS

The research is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-62071, Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-0510387, and Veterans Administration Merit Review to J. L. Messina.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Li Li, Tatyana A. Gavrikova, Jianzhong Liu, and John L. Franklin for help and comments. We thank the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comparative Pathology Laboratory for help with frozen tissue cryosection.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguirre V, Uchida T, Yenush L, Davis R, White MF. The c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase promotes insulin resistance during association with insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphorylation of Ser307. J Biol Chem 275: 9047–9054, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aguirre V, Werner ED, Giraud J, Lee YH, Shoelson SE, White MF. Phosphorylation of Ser307 in insulin receptor substrate-1 blocks interactions with the insulin receptor and inhibits insulin action. J Biol Chem 277: 1531–1537, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agwunobi AO, Reid C, Maycock P, Little RA, Carlson GL. Insulin resistance and substrate utilization in human endotoxemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 3770–3778, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altavilla D, Saitta A, Squadrito G, Galeano M, Venuti SF, Guarini S, Bazzani C, Bertolini A, Caputi AP, Squadrito F. Evidence for a role of nuclear factor-κB in acute hypovolemic hemorrhagic shock. Surgery 131: 50–58, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-β links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med 11: 191–198, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bochicchio GV, Sung J, Joshi M, Bochicchio K, Johnson SB, Meyer W, Scalea TM. Persistent hyperglycemia is predictive of outcome in critically ill trauma patients. J Trauma 58: 921–924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, Melendez PA, Hansen L, Lee J, Shoelson SE. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-β and NF-κB. Nat Med 11: 183–190, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cree MG, Wolfe RR. Postburn trauma insulin resistance and fat metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E1–E9, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dajani R, Sanlioglu S, Zhang Y, Li Q, Monick MM, Lazartigues E, Eggleston T, Davisson RL, Hunninghake GW, Engelhardt JF. Pleiotropic functions of TNF-α determine distinct IKKβ-dependent hepatocellular fates in response to LPS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G242–G252, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faingold MC, Benzadon MN, Musso C, Dinardo V, Navia D, Sinay IR. Hyperglycemia at admission to a surgical intensive care unit is a risk factor for later development of DM2. In: Abstracts of the 70th Scientific Sessions of the American Dietetic Association. Chicago, IL: Am. Diet. Assoc., 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fatourechi MM, Kudva YC, Murad MH, Elamin MB, Tabini CC, Montori VM. Hypoglycemia with intensive insulin therapy. A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized trials of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion versus multiple daily injections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 729–740, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hebert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 360: 1283–1297, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao Z, Hwang D, Bataille F, Lefevre M, York D, Quon MJ, Ye J. Serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 by inhibitor-κB kinase complex. J Biol Chem 277: 48115–48121, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gore DC, Chinkes D, Heggers J, Herndon DN, Wolf SE, Desai M. Association of hyperglycemia with increased mortality after severe burn injury. J Trauma 51: 540–544, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev 18: 2195–2224, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature 420: 333–336, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hotamisligil GS. The role of TNF-α and TNF receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. J Intern Med 245: 621–625, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hotamisligil GS, Peraldi P, Budavari A, Ellis R, White MF, Spiegelman BM. IRS-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in tumor necrosis factor-α- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Science 271: 665–668, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang S, Gavrikova TA, Pereboev A, Messina JL. Adenovirus infection results in alterations of insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E1295–E1304, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim PK, Deutschman CS. Inflammatory responses and mediators. Surg Clin North Am 80: 885–894, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krinsley JS, Grover A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med 35: 2262–2267, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laird AM, Miller PR, Kilgo PD, Meredith JW, Chang MC. Relationship of early hyperglycemia to mortality in trauma patients. J Trauma 56: 1058–1062, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li L, Messina JL. Acute insulin resistance following injury. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20: 429–435, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li L, Thompson LH, Zhao L, Messina JL. Tissue specific difference in the molecular mechanisms for the development of acute insulin resistance following injury. Endocrinology 150: 24–32, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu J, Yang D, Minemoto Y, Leitges M, Rosner MR, Lin A. NF-κB is required for UV-induced JNK activation via induction of PKCδ. Mol Cell 21: 467–480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu J, Yang H, Liu W, Cao X, Feng X. Sp1 and Sp3 regulate the basal transcription of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand gene in osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Biochem 96: 716–727, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma Y, Toth B, Keeton AB, Holland LT, Chaudry IH, Messina JL. Mechanisms of hemorrhage-induced hepatic insulin resistance: role of tumor necrosis factor-α. Endocrinology 145: 5168–5176, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma Y, Wang P, Kuebler JF, Chaudry IH, Messina JL. Hemorrhage induces the rapid development of hepatic insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G107–G115, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin 17: 107–124, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller-Jensen K, Janes KA, Wong YL, Griffith LG, Lauffenburger DA. Adenoviral vector saturates Akt pro-survival signaling and blocks insulin-mediated rescue of tumor necrosis-factor-induced apoptosis. J Cell Sci 119: 3788–3798, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mollen KP, McCloskey CA, Tanaka H, Prince JM, Levy RM, Zuckerbraun BS, Billiar TR. Hypoxia activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase via Rac1-dependent reactive oxygen species production in hepatocytes. Shock 28: 270–277, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Munoz MC, Giani JF, Mayer MA, Toblli JE, Turyn D, Dominici FP. TANK-binding kinase 1 mediates phosphorylation of insulin receptor at serine residue 994: a potential link between inflammation and insulin resistance. J Endocrinol 201: 185–197, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muruve DA, Barnes MJ, Stillman IE, Libermann TA. Adenoviral gene therapy leads to rapid induction of multiple chemokines and acute neutrophil-dependent hepatic injury in vivo. Hum Gene Ther 10: 965–976, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamori Y, Emoto M, Fukuda N, Taguchi A, Okuya S, Tajiri M, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Wada Y, Tanizawa Y. Myosin motor Myo1c and its receptor NEMO/IKK-γ promote TNF-α-induced serine 307 phosphorylation of IRS-1. J Cell Biol 173: 665–671, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakatani Y, Kaneto H, Kawamori D, Hatazaki M, Miyatsuka T, Matsuoka TA, Kajimoto Y, Matsuhisa M, Yamasaki Y, Hori M. Modulation of the JNK pathway in liver affects insulin resistance status. J Biol Chem 279: 45803–45809, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-κB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 49–62, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rohl M, Pasparakis M, Baudler S, Baumgartl J, Gautam D, Huth M, De Lorenzi R, Krone W, Rajewsky K, Bruning JC. Conditional disruption of IκB kinase 2 fails to prevent obesity-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 113: 474–481, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414: 799–806, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schinner S, Scherbaum WA, Bornstein SR, Barthel A. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Diabet Med 22: 674–682, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Song L, Li J, Zhang D, Liu ZG, Ye J, Zhan Q, Shen HM, Whiteman M, Huang C. IKKβ programs to turn on the GADD45α-MKK4-JNK apoptotic cascade specifically via p50 NF-κB in arsenite response. J Cell Biol 175: 607–617, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 85–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thomas CE, Ehrhardt A, Kay MA. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet 4: 346–358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thompson LH, Kim HT, Ma Y, Kokorina N, Messina JL. Acute muscle-type specific insulin resistance following injury. Mol Med 11–12: 715–723, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thorell A, Nygren J, Ljungqvist O. Insulin resistance: a marker of surgical stress. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2: 69–78, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N, You X, Thaler LM, Kitabchi AE. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 978–982, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, Van WE, Bobbaers H, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 354: 449–461, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 345: 1359–1367, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vriesendorp TM, DeVries JH, Hoekstra JB. Hypoglycemia and strict glycemic control in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 14: 397–402, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Walsh KB, Toledo AH, Rivera-Chavez FA, Lopez-Neblina F, Toledo-Pereyra LH. Inflammatory mediators of liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Exp Clin Transplant 7: 78–93, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Winkelman C. Inactivity and inflammation: selected cytokines as biologic mediators in muscle dysfunction during critical illness. AACN Clin Issues 15: 74–82, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wullaert A, Heyninck K, Beyaert R. Mechanisms of crosstalk between TNF-induced NF-κB and JNK activation in hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 72: 1090–1101, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu J, Kim HT, Ma Y, Zhao L, Zhai L, Kokorina N, Wang P, Messina JL. Trauma and hemorrhage-induced acute hepatic insulin resistance: dominant role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Endocrinology 149: 2369–2382, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yendamuri S, Fulda GJ, Tinkoff GH. Admission hyperglycemia as a prognostic indicator in trauma. J Trauma 55: 33–38, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Youngren JF. Regulation of insulin receptor function. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 873–891, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yuan M, Konstantopoulos N, Lee J, Hansen L, Li ZW, Karin M, Shoelson SE. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of IKKβ. Science 293: 1673–1677, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell 91: 243–252, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhai L, Ballinger SW, Messina JL. Role of reactive oxygen species in injury-induced insulin resistance. Mol Endocrinol 25: 492–502, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zick Y. Insulin resistance: a phosphorylation-based uncoupling of insulin signaling. Trends Cell Biol 11: 437–441, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zick Y. Uncoupling insulin signalling by serine/threonine phosphorylation: a molecular basis for insulin resistance. Biochem Soc Trans 32: 812–816, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]