Abstract

Elite suppressors/controllers (ES) are HIV-1–infected individuals who maintain stable CD4+ T-cell counts and viral loads of <50 copies/mL without antiretroviral therapy. Research has predominantly focused on immune factors contributing to the control of viral replication in these patients. A more fundamental question, however, is whether there are differences in the nature of CD4+ T-cell infection in ES compared with viremic patients. Here, we compare chronic progressor (CP), ES, and uninfected donors in terms of three aspects of CD4+ T-cell infection: cellular susceptibility to infection, death of infected cells, and production of virus from infected cells. Using multiple methods of infection and both single-cycle and replication-competent virus, we show that unmanipulated CD4+ T-cell populations from ES are actually more susceptible to HIV-1 infection than those populations from CP. Depletion of highly susceptible cells in CP may contribute to this difference. Using 7AAD and AnnexinV staining, we show that infected cells die more rapidly than uninfected cells, but the increased death of infected cells from CP and ES is proportional. Finally, using an assay for measuring virus production, we show that virus production by cells from CP is high compared with virus production by cells from ES or uninfected donors. This higher virus production is linked to cellular activation levels. These data identify fundamental differences in chronic infection of ES and CP that likely contribute to differential HIV-1 disease progression.

Keywords: burst size, cell death

In individual patients, the course of HIV-1 infection varies along a broad spectrum ranging from natural control of infection without antiretroviral therapy to rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells and progression to AIDS. Chronic progressors (CP) fall between these extremes and are generally placed on antiretroviral therapy when CD4+ T-cell counts drop to a clinically defined threshold. Elite suppressors (ES), in contrast, naturally control viremia to <50 copies/mL and usually maintain normal CD4+ T-cell counts (1, 2), despite ongoing viral replication (3–5). Initial studies suggested that infection with replication-deficient virus was responsible for control of viremia in ES. However, subsequent studies showed that many ES are infected with replication-competent virus (6–9) that lacks significant insertions, deletions, or substitutions (6, 7). Although the fitness of viruses amplified from ES is sometimes less than the fitness of laboratory viral strains or viruses from CP, the differences in fitness most likely reflect viral evolution in response to host immune pressure in ES and thus are not the primary cause of the control of viral replication in ES (10–12). Many of the escape mutations that affect fitness are not present in proviral DNA, which is more representative of the transmitted virus than plasma virus (4, 5, 13, 14).

Naturally, a great deal of emphasis has been placed on determining what immune responses permit ES to control viremia and maintain adequate CD4+ T-cell counts. Significant differences in the effectiveness of the CD8+ T-cell response of ES and CP have been described (15–20), and there is strong evidence that certain HLA alleles contribute to the ability of ES to control infection (1, 21, 22). However, protective HLA alleles are neither necessary nor sufficient to explain control of viral replication (23–25). We have, therefore, examined differences between ES and CP starting from the fundamental aspects of infection. The most fundamental and universal factor in HIV-1 infection is the primary target of infection, the CD4+ T cell. Regarding CD4+ T cells, viral infection requires three things: a target cell that is susceptible to infection, cell survival to permit replication of the virus, and release of virions by the infected cell.

Studies on whether CD4+ T cells from ES and CP differ in their inherent susceptibility to infection are complicated by varying culture conditions. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated CD4+ T cells from ES are susceptible to infection (7, 8, 26–30), but studies that have used CD3 stimulation to activate CD4+ T cells from ES have yielded conflicting results. One study suggested that cells from ES were resistant to infection because of selective up-regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (31), whereas another study also found resistance of ES CD4+ T cells to HIV-1 infection but showed that p21 plays no role in this phenomenon (32). A third study found that CD4+ T cells from ES were as susceptible to infection as CD4+ T cells from HIV-1 seronegative donors (9). Because activation by either method, PHA or anti-CD3 antibodies, has been shown to modulate coreceptor density, which, in turn, affects susceptibility to infection (33–35), we have studied the susceptibility of unstimulated CD4+ T cells. We found that cells from ES are at least as susceptible to infection as cells from CP and uninfected donors, if not more so (36). Susceptibility was shown with both an assay measuring fusion of the virus to the cell and an assay measuring expression of a virally encoded reporter gene (GFP) after entry, reverse transcription, and integration. Another recent study using unstimulated CD4+ T cells from ES also found that there was no block to HIV-1 integration (37).

In this study, we considered differences in HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells from ES and CP. We examined CD4+ T-cell susceptibility to infection with pseudotyped virus capable of a single cycle of infection and replication-competent virus capable of multiple cycles of replication. We also used two methods of infection, spinoculation and infection without spinoculation. These studies were conducted with freshly isolated, unactivated, primary CD4+ T cells. Our findings confirmed that cells from ES are highly susceptible to infection. We then explored the possibility that cells from different patient cohorts differ in their susceptibility to infection because of differences in the frequencies of target cell subpopulations. To this end, we identified highly susceptible cells in ex vivo infection studies and then compared the frequencies of these subsets in our patient groups. To explore potential differences in cell death between patient cohorts, we used 7AAD and AnnexinV staining to quantify death in cells from CP, ES, and uninfected donors infected ex vivo. Finally, we compared virus production by HIV-1–infected CD4+ T cells from these patient cohorts. This analysis of three critical aspects of viral infection has identified differences between CP and ES that may contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Results

Cells from ES Are at Least as Susceptible to Infection as Those Cells from CP and Uninfected Donors.

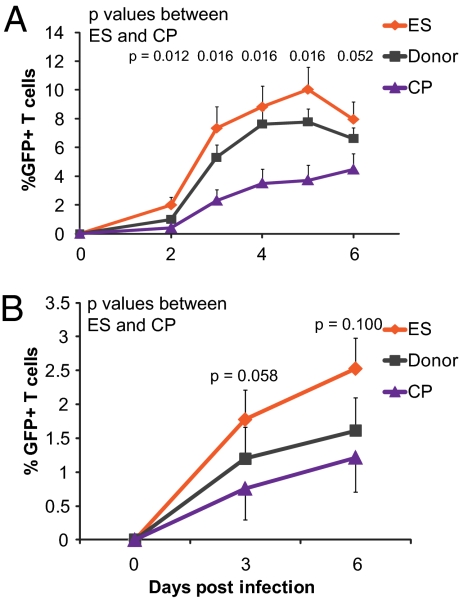

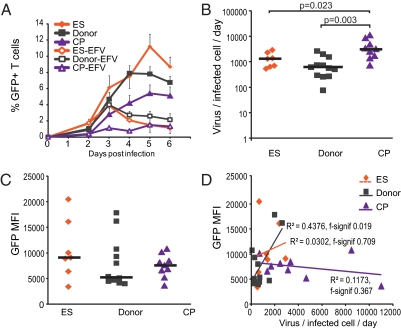

We have previously shown that freshly isolated, unstimulated CD4+ T cells from ES are at least as susceptible to infection, if not more susceptible, as CD4+ T cells from CP and uninfected donors (36). These findings were based on the fraction of infected cells measured 3 or 6 d after infection with single-cycle X4- and R5-tropic pseudoviruses through spinoculation (38). To determine whether this apparent increase in susceptibility is also observed in multiround infections, we used a replication-competent X4-tropic virus that expresses GFP in place of the nef gene. We measured GFP expression daily over the course of 6 d in cells from ES, CP, and uninfected donors (Fig. 1A). We found that neither the kinetics nor the maximum levels of infection achieved in cells from ES are different from those variables of the uninfected donors. In contrast, cells from CP were infected more slowly and to a lesser extent. To confirm that the use of spinoculation was not impacting our observation, we assessed productive infection in our cohort after infection with single-cycle X4-tropic virus expressing GFP without the use of spinoculation. We added the entry inhibitor Enfuvirtide (T20) 18 h postinfection to synchronize infection within that initial window, and we again observed a higher fraction of cells from ES expressing GFP at both days 3 and 6 postinfection compared with cells from CP (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

CD4+ T cells from ES are more susceptible to HIV-1 infection than cells from CP or donors. (A) Mean infection of unstimulated CD4+ T cells infected with replication-competent NL43 virus in which GFP was inserted into the nef gene. Infection was through spinoculation. n = 6, 9, and 6 for ES, donors, and CP, respectively. (B) Mean infection of unstimulated CD4+ T cells infected with single-cycle X4 virus without spinoculation. Virus was incubated with CD4+ T cells at 37 °C for 18 h. After 18 h, virus was removed, and the entry inhibitor T20 was added to prevent additional infection events. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 8, 9, and 8, respectively. Error bars depict SEM, and P values indicate differences between ES and CP at each time point; they are from the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Median was calculated in addition to the mean, and it was essentially equivalent.

Infection ex Vivo Does Not Correlate with Cellular Activation.

Activated CD4+ T cells are the main targets of productive HIV-1 infection. Data from several groups, however, have suggested that cells lacking activation markers are also capable of being infected, and among activated cells there are differences in susceptibility to infection (39–43). We and others have previously shown considerably higher levels of CD4+ T-cell activation in CP than ES (36, 44, 45), and activation does not correlate with susceptibility to infection ex vivo in our system (36). To investigate the subset of CD4+ T cells most susceptible to infection, we infected unstimulated CD4+ T cells from uninfected donors using either X4- or R5-tropic virus. We used uninfected donors for these studies, because using cells from infected patients may have skewed the results for populations that are expanded or depleted in infected patients. Because of the low rate of infection in cells from uninfected donors, we used spinoculation to obtain sufficient GFP+ events for infection with R5-tropic virus, and we infected with X4-tropic virus both through spinoculation and without spinoculation. We examined infection at days 3 and 6 postinfection.

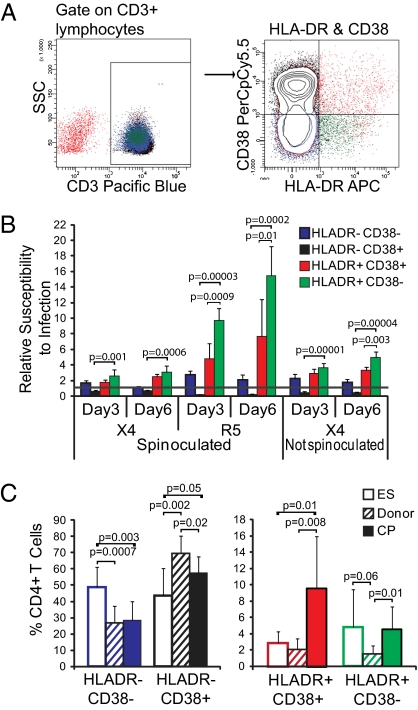

HLA-DR is up-regulated on cellular activation, and coexpression of HLA-DR with CD38 is frequently used to define activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in HIV-1 infection (18, 44, 46–49). We therefore used flow cytometry to assess expression of HLA-DR and CD38 on infected cells and collected several hundred thousand events for each infection type to obtain at least 1,000 GFP+ events. Relative susceptibility to infection was calculated by dividing the percent of GFP+ events for each subset by the percent of total T cells of each subset in the uninfected sample, with a result of greater than one indicating that the cells are preferentially infected. Representative flow cytometry data are shown in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

Activated CD4+ T cells are preferentially infected. (A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of HLA-DR and CD38 expression on CD4+ T cells from study subjects. Gating was on lymphocyte population and then CD3+ T cells, because CD4 is down-regulated on infected cells. Cells were purified CD4+ T cells that had fewer than 1% contaminating CD8+ cells (Methods). (B) Unstimulated CD4+ T cells from four to six uninfected donors were infected with X4 or R5 virus with or without spinoculation as indicated, and cells were stained with CD3, HLA-DR, and CD38 on days 3 and 6 postinfection. The percentage of GFP+ cells expressing HLA-DR and CD38 in combination was divided by the percentage of overall T cells expressing that combination to define a preference for infection. Preference is indicated by y = 1.0 line. (C) Frequency of HLA-DR and CD38 cell populations in CD4+ T cells from ES, donors, and CP. Unstimulated cells from each patient group were analyzed by flow cytometry. P values for B and C are from two-tailed Student t tests. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 8, 10, and 7, respectively.

Activated (HLA-DR+) cells were preferentially infected compared with unactivated cells. Among HLA-DR+ cells, however, HLA-DR+CD38− cells were more susceptible to infection, particularly with R5 virus, than HLA-DR+CD38+ cells (Fig. 2B). Of HLA-DR− cells, CD38− cells were slightly preferentially infected, whereas CD38+ cells were quite underrepresented in the infected cell population (Fig. 2B). Cells in the HLA-DR−CD38+ population are predominantly naïve T cells [CD45RA+C-C Chemokine Receptor 7 (CCR7)+].

As anticipated based on prior studies examining T-cell activation, CP had significantly higher levels of HLA-DR+CD38+ cells than ES (P = 0.01) (50), but ES and CP had similar levels of HLA-DR+CD38− cells (P = 0.86). HLA-DR− cells of ES were predominantly CD38−, a preferred target of infection; in contrast, HLA-DR− cells of CP were predominantly CD38+ cells, which were rarely infected in our study (Fig. 2C). Overall, however, ES and CP did not differ significantly in the frequency of HLA-DR+ cells that were highly susceptible to infection (P = 0.09). The relationship between cellular activation and susceptibility to infection does not explain the higher infection levels of ES over CP.

Memory Cells Are Most Susceptible to HIV-1 Infection and Are Overrepresented in ES.

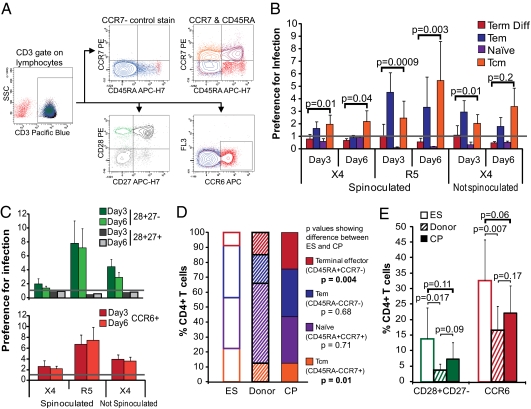

We next set out to define which cell subsets, regardless of activation state, are highly susceptible to productive infection. We used the same procedure described above to study CD4+ T cells from uninfected donor cells. Because memory cells have previously been shown to be highly susceptible to infection (39, 40, 51, 52), we chose to examine the cell surface markers CD45RA and CCR7, which distinguish memory phenotypes. CCR6, which is a memory cell marker, and the costimulatory markers CD28 and CD27 were also examined (46, 53). We explored the susceptibility of cells expressing these markers to infection, and we assessed the frequencies of these populations in our cohort of ES, CP, and uninfected donors. Representative flow cytometry data are shown in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

Memory T cells are preferentially infected. (A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD45RA, CCR7, CCR6, CD28, and CD27 expression on CD4+ T cells from study subjects. Gating was on the lymphocyte population and then CD3+ T cells, because CD4 is down-regulated on infected cells. Cells were purified CD4+ T cells that had fewer than 1% contaminating CD8+ cells (Methods). The CCR7− stain was used to set the CCR7 gate, because CCR7 staining had low MFI. (B) Unstimulated CD4+ T cells from four to six uninfected donors were infected with X4- or R5-tropic virus with or without spinoculation as indicated, and cells were stained with CD3, CD45RA, and CCR7 on days 3 and 6 postinfection. The percentage of GFP+ cells expressing the markers was divided by the percentage of overall T cells expressing that combination to define a preference for infection. Preference is indicated by y = 1.0 line, and P values comparing terminally differentiated effector and Tcm cells frequencies are shown. (C) Same as B but for CD28 and CD27 expression and CCR6 expression. (D) Frequency of CCR7 and CD45RA expressing subsets in ES, donors, and CP. Unstimulated cells from each patient group were analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) Same as D but for CD28, CD27, and CCR6 expression. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 8, 10, and 7, respectively. P values for B–E are from two-tailed Student t tests.

As anticipated, we found preferential infection of memory cells (CD45RA−), but naïve and terminally differentiated effectors were underrepresented in the infected population (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, although both effector memory (Tem cells; CD45RA−CCR7−) and central memory (Tcm cells; CD45RA−CCR7+) were preferentially infected, there was a trend to Tem cells being more preferentially infected than Tcm cells on day 3, but by day 6 postinfection, Tcm cells were more preferentially infected (Fig. 3B). Tem cells have higher levels of activation than Tcm cells, which may result in more rapid turnover of the infected Tem cells. Overall, however, the data clearly show that CD45RA− memory CD4+ T cells are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection.

CD28 and CD27 are key costimulatory molecules expressed on naïve cells and down-regulated on cellular activation. They help distinguish the status of nonnaïve T-cell subsets: CD27 is down-regulated before CD28 on CD4+ T cells, and its down-regulation is associated with loss of proliferative ability (54, 55). By staining with CD28 and CD27, we observed that CD28+CD27− cells were more susceptible to infection than CD28+CD27+ cells, suggesting that cells at an early phase of expansion are highly susceptible to infection (Fig. 3C). CD28−CD27− and CD27+CD28− cells were very rare in the peripheral blood cells of the uninfected donors in which these studies were conducted. Additionally, we examined the susceptibility of CCR6-expressing cells. CCR6 is a chemokine receptor expressed on memory T cells, and it is critical for recruitment during immunological responses. CCR6+ cells have previously been shown to be infected at a high frequency in vivo (52). Cells expressing CCR6 were also preferentially infected (Fig. 3C), supporting the observation that memory cells are significant targets of infection. These preferences held over both days 3 and 6 postinfection.

Because we were staining for these cellular markers after infection, it was possible that the phenotypes that we were observing were the result of infection and not related to susceptibility. For example, CD45RA+ cells may have been highly susceptible to infection, but if they were changing phenotype to a CD45RA− subtype upon infection, we would have missed this observation. To address this issue, we isolated CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells using bead depletion of CD45RO and CD45RA, respectively. Our CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ cells were less than 1% CD45RO+ and CD45RA+, respectively. We found that only the CD45RO+ cells were infected with R5-tropic virus (1.9–2.1% in CD45RO+ cells vs. 0.1% in CD45RA+ cells). X4-tropic virus infected both CD45RA and CD45RO cells but infected CD45RA less than CD45RO (CD45RO+, 10.6–11.4%; CD45RA+, 5–7.7%). Importantly, there was no change in the CD45RO or CD45RA expression when we looked both 3 and 6 d after infection.

We next used the same markers that we had used to assess susceptibility to compare the frequency of the preferentially infected cell subtypes in uninfected, freshly isolated CD4+ T cells of ES, CP, and uninfected donors. ES had significantly higher frequencies of central memory (CD45RA−CCR7+) T cells than CP, whereas CP had significantly higher frequencies of terminally differentiated effectors than ES (CD45RA+CCR7−; P = 0.01 and 0.004, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Central memory T cells were preferentially infected, whereas terminally differentiated cells were not infected, which was shown in Fig. 3B. ES also had higher frequencies of CCR6 and CD28+CD27− T cells than CP, although this finding was not statistically significant (P values of 0.06 and 0.11, respectively) (Fig. 3E).

Overall, ES had a higher frequency of the cell subtypes that were most susceptible to infection, including central memory cells, CD28+CD27− cells, and CCR6+ cells.

CD4+ T Cells from CP Die More Rapidly than Those Cells from ES or Uninfected Donors.

Previous studies have shown differences in cell death in infected patients. Cells from CP exhibit higher cell death than uninfected donors overall (56, 57), and one study found that memory cells from ES persist longer than those cells from CP through a FOX03a-mediated pathway (58). We were interested, however, in the death rate of infected cells relative to overall cell death. If infected cells from ES died more quickly than infected cells from CP, this finding might represent an innate CD4+ T-cell mechanism for inhibiting HIV-1 replication. A higher death rate of infected cells from CP, in contrast, would impact our observation that ES have higher infection in vitro, which was measured by GFP expression.

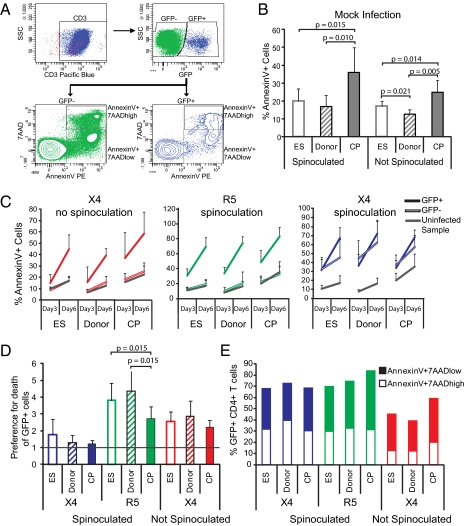

To evaluate these possibilities, we infected cells from ES, CP, and uninfected donors with X4- and R5-tropic single-cycle virus through spinoculation. We also infected cells with X4-tropic single-cycle virus without spinoculation, because the use of spinoculation might lead to nonphysiological infection of CD4+ T cells, potentially skewing our results. We washed cells after infection and added the entry inhibitor T20 18 h postinfection to prevent additional infection by any remaining virus particles. Using 7AAD and AnnexinV staining, we assessed cell death 3 and 6 d after ex vivo infection and in mock-infected control samples. AnnexinV binds phosphatidylserine, which is exposed on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane only when cells are undergoing necrosis or apoptosis; 7AAD binds DNA but is membrane-impermeable and, therefore, can only access DNA on cell death. Results from a representative infected sample are shown in Fig. 4A. We found that there was a higher frequency of dead cells in mock-infected samples from CP than samples from ES or uninfected donors (Fig. 4B). This result is likely because of the high levels of activated and terminally differentiated cells in CP (Figs. 2C and 3D).

Fig. 4.

Death rate of infected and uninfected cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry data depicting gating on lymphocyte population followed by CD3+ cells and then considering GFP+ and GFP− cells for the AnnexinV analysis. For all data shown (with the exception of E), the total AnnexinV+ population was considered. (B) Average of AnnexinV+ CD4+ T cells from ES, donors, and CP on day 6 of culture without infection. Error bars are SD. (C) GFP+ (infected) cells are dying more than GFP− (uninfected) cells. Percentage of CD4+ T cells that are GFP+ (solid lines) cells, GFP− (hollow lines) cells, and cells from an uninfected control sample (gray) dying on days 3 and 6 after infection with X4 virus without spinoculation, R5 virus with spinoculation, and X4 virus with spinoculation. Averages and SDs are shown. (D) The percentage of GFP+AnnexinV+ cells was divided by the percentage of GFP−AnnexinV+ cells in each sample of cells from ES, donors, and CP infected with X4 virus through spinoculation, R5 virus through spinoculation, and X4 virus without spinoculation on day 6 postinfection. Averages and SDs are shown. The line at y = 1 indicates preference for death of GFP+ cells. (E) Average of AnnexinV+7AADhigh and 7AADlow cell populations in ES, donors, and CP for GFP+ CD4+ T cells. P values are from Wilcoxon signed rank test. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 8, 9, and 8, respectively.

Ex Vivo Infected CD4+ T Cells Die at Higher Rates than Uninfected Cells, but This Difference Is Consistent Across Patient Cohorts.

To determine the impact of ex vivo infection on cell death, we evaluated AnnexinV binding in our ex vivo infected samples. We found that GFP+ cells were dying more rapidly than GFP− cells after X4 infection without spinoculation and R5 infection through spinoculation (Fig. 4C Left and Center). This finding was true for all patient groups. We also observed that samples infected with X4 virus through spinoculation had a high rate of death of both GFP+ and GFP− cells (Fig. 4C Right). Spinoculation can lead to viral entry in naïve CD4+ T cells that might otherwise not be susceptible to infection. A recent study has shown that abortive infection, in which virus fuses and begins RT but does not complete it, results in apoptosis of the cell (59). We posit that the high frequency of cell death in GFP− cells infected with X4 virus by spinoculation is because of naïve or quiescent cells that have undergone fusion and incomplete RT but have failed to integrate the viral genome and express GFP.

Although death of GFP+ cells was high across all patient groups, the critical question was whether ex vivo infection with the GFP-expressing virus leads to disproportionate cell death in CP vs. ES. After normalizing the percentage of AnnexinV+ GFP+ cells to the percentage of AnnexinV+ GFP− cells, we observed no difference between ES and CP in X4 infection with or without spinoculation (Fig. 4D). In contrast, in our samples that were infected with R5 virus through spinoculation, we observed a higher preference for death of GFP+ over GFP− cells in ES compared with CP (Fig. 4D). However, these preferences were similar to those preferences observed for uninfected donors and, therefore, likely do not represent an innate mechanism of defense that is unique to ES.

Finally, we also looked at early (AnnexinV+7AADlow) compared with late (AnnexinV+7AADhigh) stages of cell death across our patient cohorts. We found no differences between patient groups in the proportion of patient cells in each stage of cell death (Fig. 4E).

In sum, after X4 infection through spinoculation, GFP+ and GFP− cells were dying at approximately equivalent rates, likely because of nonphysiological viral entry into quiescent CD4+ T cells. After spinoculation with R5 virus or infection with X4 virus without spinoculation, GFP+ cells were dying at higher levels than GFP− cells, but this preferential death of GFP+ cells was largely equivalent between CP and ES. ES and uninfected donors exhibited a larger increase in death of GFP+ cells over GFP− cells after infection with R5-tropic virus, possibly reflecting the fact that CP have higher baseline death of GFP− cells.

Infected CD4+ T Cells from CP Produce Larger Quantities of Virus than Infected CD4+ T Cells from ES.

Production of virions from an infected cell is the final stage of the viral life cycle. The burst size of HIV-1 is unknown, but estimates for simian immunodeficiency virus burst size are around 5 × 104 virions per infected cell (60). Burst size (defined as the number of virions produced from any one infected cell) plays an important role in determining the fate of an infection (61, 62). Although both in vivo and in vitro estimates of burst size exist for chronic progressors and uninfected donors (41, 60, 61, 63, 64), such measurements are lacking for ES. It could be hypothesized that the ability of ES to control viral replication is because of lower burst size of their cells. Additionally, burst size may vary depending on the dominant infected cell population, both in terms of the lifespan of the cell and the cellular factors that may vary depending on the cell subtype. A study using p24 as a measure of burst size found that naïve cells produced fewer virions per infected cell than memory cells (41).

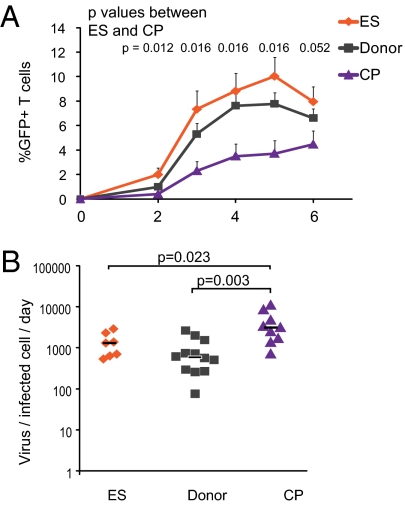

We examined HIV-1 burst size using a budding assay. Freshly isolated, unstimulated, primary CD4+ T cells were infected with replication-competent X4-tropic virus by spinoculation; 2 d postinfection, cells were washed rigorously and plated at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL. Efavirenz was added to block additional infection (Fig. 5A). The amount of viral RNA produced between days 2 and 3 postinfection was measured by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and then normalized by the number of GFP+ cells to obtain the rate of budding per infected cell. The units were, therefore, viral RNA day−1 infected cell−1. The upstream primer used for qRT-PCR is in the 3′ LTR region, and the downstream primer hybridizes to the polyA at the end of the viral RNA transcript. This primer selection prevents the detection of background proviral DNA, and, in a control experiment, our assay did not detect up to 106 copies NL43 plasmid, which ensures a highly sensitive and specific quantification scheme.

Fig. 5.

Infected cells from CP produce more virus than cells from ES or donors. (A) Infection data are the same as those data shown in Fig. 1A, with the addition of data for the percent GFP after the addition of Efavirenz, which is indicated by EFV. Efavirenz was added at day 2 postinfection to block new infection events so that viral budding could be quantified. Mean is shown, and error bars are SEM. (B) Virus production was measured by quantifying viral mRNA released from infected cells. Viral mRNA per infected cells was then calculated using the GFP percent shown in A. P values are derived from the Wilcoxon signed rank test, and black bars indicate median. (C) MFI of GFP for infected cells; black bars indicate median. Differences were insignificant by the Wilcoxon signed ranked test (P > 0.3 for all). (D) MFI of GFP for infected cells was measured and correlated to viral production per infected cell for all three patient groups. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 7, 12, and 9, respectively.

Cells from CP produced significantly more virus per infected cell per 1 d than cells from ES (median = 3,113 and 1,298 RNA copies/infected cell per d, respectively; P = 0.023) (Fig. 5B). Production of virus from cells of ES, in contrast, was similar to the production of uninfected donors (median = 1,298 vs. 586 RNA copies/infected cell per d, respectively; P = 0.34). One study has suggested that there is a block in transcription in ES (31). Therefore, we also examined levels of viral gene expression in infected cells using GFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in cells from ES, CP, and uninfected donors. There was no statistically significant difference in GFP MFI between groups (Fig. 5C) (P > 0.05). We also looked at the correlation between GFP MFI and virus production. A strong correlation would suggest that increased transcription leading to increased GFP MFI directly impacted the amount of virus produced by an infected cell. We found a slight correlation for uninfected donors (f significance = 0.019), but the correlation was not significant for ES or CP (Fig. 5D).

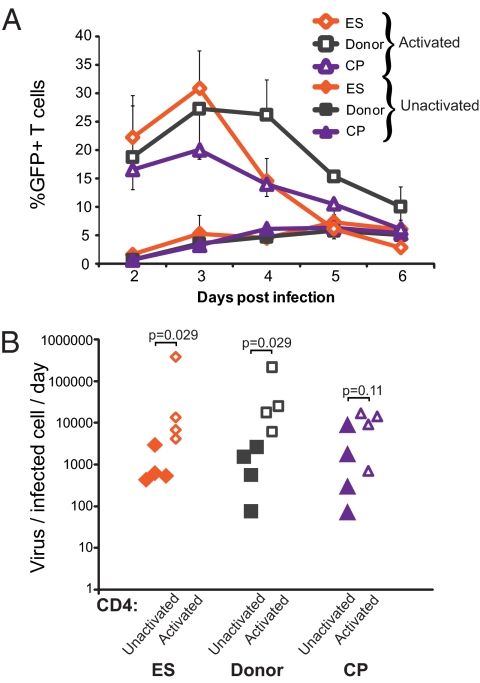

One of the major differences between ES and CP is the high frequency of activated cells in CP. High CD8+ T-cell activation has been shown to correlate with poor disease progression (50, 65, 66), and CD4+ T-cell activation contributes to disease pathogenesis by increasing the frequency of target cells available for infection (67). In our cohort, ES and CP had similar levels of CD4+HLA-DR+CD38− cells, but CP had significantly more CD4+HLA-DR+CD38+ cells (Fig. 2C). We hypothesized, therefore, that activated cells produced more virus per infected cell than unactivated cells. To test this hypothesis, we randomly selected a group of four ES, four CP, and four uninfected donors and compared the budding capacity of unactivated cells and cells exogenously activated with PHA.

Infection of activated cells resulted in dramatically higher infection than we had observed with infection of unactivated cells (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, although the number of infected cells for ES was higher than for CP or uninfected donors early after infection (not significant, P = 0.12 between ES and CP), there was a decrease in the percent of GFP+ cells for ES at day 4 postinfection. Exogenous activation of cells from all patient groups also resulted in higher levels of virus produced per infected cell (Fig. 6B). Using qPCR, we observed that the cellular factors Rab9 and TSG101 are up-regulated in CD3/28- and PHA-activated CD4+ T cells compared with unstimulated CD4+ T cells from uninfected donors. These factors are involved in virus assembly and budding (68, 69), and their up-regulation may help to explain the high budding of activated CD4+ T cells. Because CP have higher CD4+ T-cell activation than ES or uninfected donors, the higher budding capacity of activated cells likely explains the high budding capacity of cells from CP.

Fig. 6.

Activation of T cells increases virus production per infected cell. (A) GFP expression of cells that were activated with PHA (open symbols) or not activated (solid symbols) for ES, donors, and CP are shown. Averages are shown, and error bars are SEM. (B) Virus produced per infected cell per day for both activated (open symbols) and unactivated (solid symbols) CD4+ T cells from the patient groups. P values are from Wilcoxon signed rank tests. For ES, donors, and CP, n = 4 for all groups.

Discussion

Understanding the factors necessary for host control of HIV-1 infection has been a focus of study for over a decade, but the mechanisms by which ES naturally control viremia are still not fully understood. In this study, we explored three critical stages of viral infection using autologous CD4+ T cells from HIV-1–infected CP and ES and from uninfected donors. We observed that cells from ES are more susceptible to ex vivo HIV-1 infection than those cells from CP and they exhibit susceptibility comparable with cells from uninfected individuals. Additionally, HIV-1 preferentially targets memory CD4+ T cells that are present at higher frequencies in ES than CP, likely because of the depletion of highly susceptible cells in CP. We found no difference in the death of infected cells in ES and CP, making it unlikely that faster death of infected cells might explain the observed differences in rates of infection. However, we found that infected cells from CP produce more viruses per infected cell than those cells from ES. This finding is likely caused by the high frequency of activated cells in CP.

Several groups, including our own group, have recently addressed the issue of inherent susceptibility of cells from different individuals to HIV-1 infection. The most significant difference between our study and studies from other groups is our use of freshly isolated, unactivated CD4+ T cells for evaluating susceptibility to infection. By omitting an exogenous activation step, we avoid artificial alterations of coreceptor expression (33–35). In addition, our side by side comparison of infection through spinoculation and without spinoculation addresses the issue of whether nonphysiological methods of infection bias susceptibility results. Of note, we did use exogenous activation of CD4+ T cells with PHA and CD3 and CD28 antibodies in a portion of this study to evaluate the impact of activation on budding and cell susceptibility to infection. We measured GFP expression of activated cells over time and found that exogenous activation resulted in considerably higher GFP expression in all patient cohorts (Fig. 6B) than the expression that was seen in unactivated cells (Fig. 1 A and B). Moreover, exogenous activation impacted the kinetics of infection. Although infection was higher in ES early in infection, there was a dramatic change around day 4 postinfection; at that point, cells from ES seemed to have the lowest infection of all patient groups. This finding suggests that exogenous activation may inadvertently alter the results of infection susceptibility studies. The impact of exogenous cellular activation on overall cell death and infected cell death may be worth examining in the future.

We posited that the high susceptibility of cells from ES might be because of the depletion of target cells in CP. Our study used cellular markers that define memory cells and other previously identified HIV-1–susceptible cells and calculated the degree of preferential infection of these subtypes. We then analyzed the frequency of highly susceptible cells in our patients. ES had a higher frequency of the cell subtypes most susceptible to infection, likely because these susceptible subsets were depleted in CP because of exposure to high levels of viremia and ongoing viral replication in these patients for several years. Specifically, ES had a higher frequency of Tcm cells than CP, and these cells were highly susceptible to infection. CP, however, had a higher frequency of terminally differentiated effector cells than ES, and these cells underwent very little infection. Importantly, although ES may have a higher frequency of cells that are susceptible to infection, this finding does not necessarily translate to more infection events in vivo. Many ES have a highly effective Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte (CTL) response that can effectively suppress viral replication ex vivo (18, 70). CTL would have a significant impact on dampening viral replication in vivo, despite the presence of potential target cells.

Interestingly, we observed that uninfected donors had lower frequencies of the highly susceptible cells and lower cellular activation than CP, but they had similar or higher (not significant) levels of infection than CP. Our study examined cellular subtypes that have been predicted to have differing susceptibilities to HIV-1 infection, but a more extensive, multiparameter assessment of cellular markers to identify primary targets of infection could be of great use in understanding HIV-1 cellular susceptibility in the future.

One potential drawback of using the percent of GFP-positive cells as a readout of infection is that infected cells from ES and CP may actually differ in their death rate. Rapid induction of cell death after infection could serve as a mechanism of viral control in ES. Alternatively, elevated death of infected cells from CP could have biased our susceptibility data because the GFP readout would have inadvertently excluded the disproportionate number of dead cells. We addressed these possibilities by thoroughly examining cell death in uninfected and infected CD4+ T cells from our ES, CP, and uninfected donor cohorts.

As we anticipated based on previous reports (56, 57), we observed higher cell death of both infected and uninfected CD4+ T cells from CP compared with ES or uninfected donors. We also observed that infected cells were dying at higher levels than uninfected cells in all patient groups. Critically, however, the increased death of infected cells from CP and ES was proportional, although ex vivo cells from CP died more rapidly than uninfected cells, the ex vivo cells of ES and uninfected donors died as well. These data suggest that it is very unlikely that infected cells from ES were dying more slowly than those cells from CP and thereby were biasing our susceptibility results. Additionally, the idea that differences in infected cell death serve as a mechanism of control in ES is not supported by these data; although ES had a higher increase in death of GFP+ cells than CP after infection with R5-tropic virus, this trend was also seen in uninfected donors.

The final requirement for virus propagation in CD4+ T cells is that target cells permit the production of new virions. Differences in virus production could play a causative role in determining disease progression if the discrepancies are caused by innate cellular factors. For example, a cellular factor needed for transcription elongation of the integrated virus (31) or virus particle assembly and budding could exert differential influence over the rate of virus production per infected cell. We therefore compared HIV-1 budding from cells of ES, CP, and uninfected donors and observed that cells from CP produced significantly more virus per infected cell than cells from ES or uninfected donors. Budding from cells of ES and uninfected donors, in contrast, was similar.

We posited that the higher budding from cells of CP was a result of differences in the cellular activation level caused by the high-level viremia in these patients and not an innate difference that would cause specific disease progression. We examined the impact of exogenous cellular activation on viral budding and found that activated cells produced considerably more virus than unactivated cells across all patient groups. Sequential Analysis Gene Expression (SAGE) analysis recently performed by our group (71) shows that activated CD4+ T cells universally have higher expression of cellular factors like Rab9 (68), Tip47 (72), and TSG101 (69), which are involved in virus assembly and budding. Using qPCR, we confirmed this finding, observing that Rab9 and TSG101 are up-regulated in CD4+ T cells activated with PHA or CD3 and CD28 antibodies compared with unstimulated CD4+ T cells from uninfected donors. Thus, the high budding capacity of cells from CP is likely the result of elevated immune activation in these patients.

The concept that ES have cells that are more susceptible to infection than cells from CP is not intuitive. ES have extremely low levels of viral replication compared with CP and much slower rates of disease progression in vivo. Our data show definitively, however, that CD4+ T cells from ES are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection, and our exploration of cell subtype frequencies, infected cell death, and viral budding contribute significantly to understanding chronic infection in HIV-1–infected patients. Although it is important to keep in mind that the cells used in these studies have been exposed to highly variable conditions in vivo, our data suggest that it is unlikely that CD4+ T cells from ES are inherently resistant to infection or die more rapidly when infected than their counterparts from CP. Additionally, we show that infected CD4+ T cells from CP produce significantly more virus per cell than those cells from ES and that this difference is most likely attributable to the high level of cellular activation in CP.

Methods

Patient Data.

ES have been infected for an average of 10.4 y and maintain an average CD4+ T-cell count of 949 cells/μL (range = 447–1,468 cells/μL). All ES have undetectable (<50 copies/mL) viral loads. CP have been infected for an average of 8.9 y and have an average CD4+ T-cell count of 470 cells/μL (range = 213–970 cells/μL). CP are not on antiretroviral therapy, and the median viral load of CP is 22,220 copies/mL. Donors are HIV-1–negative blood donors.

Investigators were blinded to the HIV-1 status of all patients throughout these studies.

Viruses and Susceptibility Studies.

X4- and R5-tropic single-cycle, pseudotyped virus used for cell death studies and subtype analysis is as described (73). Briefly, X4 and R5 env vectors were cotransfected with an NL43 plasmid in which GFP was engineered into a portion of env (NL43eGFP), resulting in replication of incompetent virus. Virus used for the budding assays was replication-competent. GFP was engineered into nef (NL43nGFP), permitting detection of infected cells by flow cytometry while permitting viral replication.

CD4+ T-Cell Purification.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from ES, CP, and uninfected donors were isolated using Ficoll gradient separation. CD4+ T cells were purified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the Miltenyi Human CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions (130-091-155; Miltenyi). Purity of CD4+ T cells was confirmed using flow cytometry: 0.1 × 106 cells were stained with CD3-FITC, CD8-APC-H7, CD16-PE, and CD56-PE (BD). If cells had more than 1% CD3+8+ or CD3−CD16+CD56+ cells, then isolation was repeated if there were sufficient cells available (percent CD3+CD8+ range = 2.1–0%, median = 0.1%, percent CD3−CD16/56+ range = 3.1–0%, median = 0.4%). In six ES, three uninfected donors, and two CP, we measured the percentage of CD8+ T cells present in infected samples 5 d after infection. We did this measurement to ensure that the CD8+ T cells were not expanding on ex vivo infection of the sample, because this expansion could potentially impact the levels of infection. We saw no expansion of the CD8+ T-cell population in any patient group, with an average change in CD8+ T-cell counts between day 0 and day 5 of 0.028%, −0.006%, and −0.37% for ES, donors, and CP, respectively.

Susceptibility of Cells to Infection.

Freshly isolated, highly purified CD4+ T cells (4 × 106) isolated from patients as described above were infected with an X4-tropic, replication-competent virus that has GFP engineered in place of the nef gene at an multiplicity of infection (MOI) of less than 0.01. Infection was through spinoculation as described (38) at 1,200 × g for 2 h, with cells plated in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Uninfected cells were also spinoculated as a control (mock-infected). After infection, supernatant containing unbound virus was removed, and cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Cells were then placed in a 37 °C incubator. Cells were plated at 1 × 106/mL in media, and the percent of GFP+ cells was read on FACS Canto II daily; 30,000–50,000 events per sample were collected.

For infection with single-cycle virus without spinoculation, CD4+ T cells purified as above from ES, CP, and uninfected donors were infected with X4-tropic single-cycle, pseudotyped virus at an MOI of less than 0.1. Cells were plated at 1 × 106/mL RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/strep in flat-bottomed plates, and virus was added to the media. Cells were then placed in a 37 °C incubator; 18 h after infection, supernatant was removed, and cells were resuspended in 1 μM T20 to block additional infection events. Cells were pelleted and analyzed for GFP expression using the BD FACS Canto II with FACSDiva software 72 and 144 h after the addition of T20. At least 200,000 events per sample were collected.

Cell Subtype Analysis.

For subtype analysis of patient cells, isolated CD4+ T cells were stained with the following combinations of antibodies: CD3-Pacific Blue, CCR7-PE (clone 150503), HLA-DR-APC, CD45RA-APC-H7, and CD38-PerCpCy5.5; CD3-Pacific Blue, CD28-PE, CD45RA-APC, and CD27-APC-H7; and CD3-Pacific Blue and CCR6-APC. All antibodies were from BD. Cells were analyzed using the BD FACS Canto II with FACSDiva software. For patient subtype analysis, at least 30,000 events were collected.

To determine cell subtypes that were preferentially infected, CD4+ T cells purified as above from four to six uninfected donors were infected with and without spinoculation with X4- and R5-tropic single-cycle, pseudotyped virus. Spinoculation was conducted with infection of CD4+ T cells in 50-mL conical tubes; uninfected cells were also spinoculated as a control (mock-infected). After infection, supernatant containing unbound virus was removed, and cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/strep. Cells were plated at 1 × 106/mL in flat-bottomed plates (usually 1 × 106 per well of a 24-well plate depending on the number of cells isolated). Cells were then placed in a 37 °C incubator. For cells that were infected without spinoculation, cells were plated at 1 × 106/mL RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/strep in flat-bottomed plates, and virus was added to the media; 18 h after infection, supernatant was removed, and 18 h after infection, all cells, spinoculated or not spinoculated, were resuspended in 1 μM T20 to block further infection events. Cells were pelleted and stained with the same combination of antibodies shown above for patient subtype analysis 72 and 144 h after the addition of T20; 200,000–2,000,000 events per sample were collected to achieve 1,000 or more GFP+ events. Preferential infection was assessed by dividing the percentage of GFP+ cells that were expressing a given set of markers by the percentage of CD3+ cells overall expressing those markers.

Isolation of CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells was done by negative selection with Miltenyi Biotech CD45RO Microbeads and CD45RA Microbeads, respectively. Purified CD4+ T cells were incubated with the beads as per the manufacturer's instructions, and the purity of the isolated populations was confirmed using flow cytometry analysis with CD45RA-APC, CD45RO-PE, CD8-APC-H7, and CD3-FITC. Cells were then infected with X4- and R5-tropic virus through spinoculation, and changes in CD45RA and CD45RO expression were assessed 3 and 6 d postinfection.

Analysis of Cell Death.

Purified CD4+ T cells were infected with X4- and R5-tropic single-cycle, pseudotyped virus with or without spinoculation at an MOI of less than 0.1. Infection was conducted as described for cell subtype analysis.

Cells were pelleted and stained with CD3-Pacific Blue, 7AAD, and AnnexinV-PE according to the manufacturer's instructions (559763; BD) 72 and 144 h after the addition of T20. CD3-Pacific Blue was added at the same time as the 7AAD and AnnexinV. Test stains were done to ensure that this combination would not result in overstaining by CD3 antibody. Cells were analyzed using the BD FACS Canto II with FACSDiva software. Between 100,000 and 700,000 events were collected with the goal of achieving 2,000 GFP+ events for each sample on day 6 postinfection. For one infection state (each for two samples—both CP), we were unable to collect 2,000 events but had over 1,000 events for each. Preference for death of infected cells was analyzed by dividing the percentage of GFP+ cells that were expressing AnnexinV by the percentage of CD3+ cells overall expressing AnnexinV.

Analysis of Viral Budding.

Freshly isolated CD4+ T cells (4 × 106) isolated from patients as described above were infected with X4-tropic, replication-competent virus that has GFP engineered in place of the nef gene at an MOI of 0.01. Infection was through spinoculation at 1,200 × g for 2 h, with cells plated in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Cells were then placed in a 37 °C incubator. After 2 d, 1 × 106 cells were washed five times in PBS and brought up in 1 mL media containing Efavirenz at a concentration of 8 μM to block additional rounds of infection. A 150-μL aliquot of cell-free supernatant was taken. On day 3, another 150-μL cell-free supernatant aliquot was taken, and the percent of GFP+ cells was read with the FACS Canto II. The supernatant aliquots were spun down at 450 x g for 15 min to pellet cell debris; 140 μL cell-free aliquot were used for RNA extraction using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScriptIII enzyme from Invitrogen. Virus was quantified using a qPCR based assay. Briefly, the upstream primer hybridizes to the 3′ LTR region, and the downstream primer hybridizes to the last 5 nt in the viral RNA plus 25 adenine nt. This process ensures that only polyadenylated viral RNA will be amplified, even in the presence of contaminating genomic DNA. The rate of virus production per day was calculated as the difference between the amounts of virus produced between days 2 and 3. This amount was normalized to the number of GFP+ cells in day 3 to obtain the amount of virus produced per infected cell. For the PHA-activated samples, the average number of GFP+ cells in days 2 and 3 was used for this normalization.

Calculating MOI.

Tissue Culture Infection Dose 50 (TCID50) was calculated by the Spearman–Karber formula after infecting 0.1 × 106 activated CD4+ T cells from uninfected donors with serially diluted X4-tropic, replication-competent virus and X4- and R5-tropic single-cycle virus used in these experiments; pfu per milliliter were calculated from TCID50 by multiplying by 0.7. Then, MOI was calculated by multiplying the pfu per milliliter by the number of milliliters of virus used in the experiment and then dividing this number by the number of cells infected.

Ethics Statement.

All studies were approved by Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was provided by all study participants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Maria Salgado for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.F.S.) and National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AI080328 (to J.N.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 15025.

References

- 1.O'Connell KA, Bailey JR, Blankson JN. Elucidating the elite: Mechanisms of control in HIV-1 infection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migueles SA, Connors M. Long-term nonprogressive disease among untreated HIV-infected individuals: Clinical implications of understanding immune control of HIV. JAMA. 2010;304:194–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mens H, et al. HIV-1 continues to replicate and evolve in patients with natural control of HIV infection. J Virol. 2010;84:12971–12981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00387-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connell KA, et al. Control of HIV-1 in elite suppressors despite ongoing replication and evolution in plasma virus. J Virol. 2010;84:7018–7028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00548-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salgado M, et al. Evolution of the HIV-1 nef gene in HLA-B*57 positive elite suppressors. Retrovirology. 2010;7:94. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey JR, et al. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a patient who developed AIDS to an elite suppressor. J Virol. 2008;82:7395–7410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00800-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blankson JN, et al. Isolation and characterization of replication-competent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a subset of elite suppressors. J Virol. 2007;81:2508–2518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamine A, et al. Replication-competent HIV strains infect HIV controllers despite undetectable viremia (ANRS EP36 study) AIDS. 2007;21:1043–1045. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280d5a7ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julg B, et al. Infrequent recovery of HIV from but robust exogenous infection of activated CD4(+) T cells in HIV elite controllers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:233–238. doi: 10.1086/653677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brumme ZL, et al. Reduced replication capacity of NL4-3 recombinant viruses encoding reverse transcriptase-integrase sequences from HIV-1 elite controllers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fe9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miura T, et al. HLA-B57/B*5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte [corrected] recognition. J Virol. 2009;83:2743–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02265-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassen KG, et al. Elite suppressor-derived HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins exhibit reduced entry efficiency and kinetics. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000377. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey JR, Williams TM, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Maintenance of viral suppression in HIV-1-infected HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors despite CTL escape mutations. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1357–1369. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey JR, Brennan TP, O'Connell KA, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Evidence of CD8+ T-cell-mediated selective pressure on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef in HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors. J Virol. 2009;83:88–97. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01958-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferre AL, et al. Mucosal immune responses to HIV-1 in elite controllers: A potential correlate of immune control. Blood. 2009;113:3978–3989. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betts MR, et al. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006;107:4781–4789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migueles SA, et al. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/ni845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sáez-Cirión A, et al. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6776–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611244104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emu B, et al. Phenotypic, functional, and kinetic parameters associated with apparent T-cell control of human immunodeficiency virus replication in individuals with and without antiretroviral treatment. J Virol. 2005;79:14169–14178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14169-14178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersperger AR, et al. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulder PJ, Watkins DI. Impact of MHC class I diversity on immune control of immunodeficiency virus replication. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:619–630. doi: 10.1038/nri2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hersperger AR, Migueles SA, Betts MR, Connors M. Qualitative features of the HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell response associated with immunologic control. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:169–173. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283454c39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Migueles SA, et al. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2709–2714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050567397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereyra F, et al. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:563–571. doi: 10.1086/526786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emu B, et al. HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses may contribute to the control of human immunodeficiency virus infection, but such responses are not always necessary for long-term virus control. J Virol. 2008;82:5398–5407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sáez-Cirión A, Shin SY, Versmisse P, Barré-Sinoussi F, Pancino G. Ex vivo T cell-based HIV suppression assay to evaluate HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1033–1041. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell KA, Han Y, Williams TM, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Role of natural killer cells in a cohort of elite suppressors: Low frequency of the protective KIR3DS1 allele and limited inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vitro. J Virol. 2009;83:5028–5034. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02551-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey JR, et al. Neutralizing antibodies do not mediate suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite suppressors or selection of plasma virus variants in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2006;80:4758–4770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4758-4770.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi SK, Siliciano JD, Bailey JR, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Role of APOBEC3G/F-mediated hypermutation in the control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite suppressors. J Virol. 2008;82:3125–3130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01533-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang B, et al. Comprehensive analyses of a unique HIV-1-infected nonprogressor reveal a complex association of immunobiological mechanisms in the context of replication-incompetent infection. Virology. 2002;304:246–264. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, et al. CD4+ T cells from elite controllers resist HIV-1 infection by selective upregulation of p21. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1549–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI44539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saez-Cirion A, et al. Restriction of HIV-1 replication in macrophages and CD4+ T cells from HIV controllers. Blood. 2011;118:955–964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll RG, et al. Differential regulation of HIV-1 fusion cofactor expression by CD28 costimulation of CD4+ T cells. Science. 1997;276:273–276. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bleul CC, Wu L, Hoxie JA, Springer TA, Mackay CR. The HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are differentially expressed and regulated on human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1925–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agrawal L, et al. Role for CCR5Delta32 protein in resistance to R5, R5X4, and X4 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary CD4+ cells. J Virol. 2004;78:2277–2287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2277-2287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabi SA, et al. Unstimulated primary CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-positive elite suppressors are fully susceptible to HIV-1 entry and productive infection. J Virol. 2011;85:979–986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01721-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graf EH, et al. Elite suppressors harbor low levels of integrated HIV DNA and high levels of 2-LTR circular HIV DNA compared to HIV+ patients on and off HAART. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001300. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Malim MH. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol. 2000;74:10074–10080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10074-10080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenchley JM, et al. T-cell subsets that harbor human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vivo: Implications for HIV pathogenesis. J Virol. 2004;78:1160–1168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1160-1168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heeregrave EJ, et al. Lack of in vivo compartmentalization among HIV-1 infected naïve and memory CD4+ T cell subsets. Virology. 2009;393:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eckstein DA, et al. HIV-1 actively replicates in naive CD4(+) T cells residing within human lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 2001;15:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostrowski MA, et al. Both memory and CD45RA+/CD62L+ naive CD4(+) T cells are infected in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1999;73:6430–6435. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6430-6435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang ZQ, et al. Roles of substrate availability and infection of resting and activated CD4+ T cells in transmission and acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5640–5645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308425101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunt PW, et al. Relationship between T cell activation and CD4+ T cell count in HIV-seropositive individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:126–133. doi: 10.1086/524143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bello G, et al. Immune activation and antibody responses in non-progressing elite controller individuals infected with HIV-1. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1681–1690. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chattopadhyay PK, Roederer M. Good cell, bad cell: Flow cytometry reveals T-cell subsets important in HIV disease. Cytometry A. 2010;77:614–622. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramzaoui S, et al. During HIV infection, CD4+ CD38+ T-cells are the predominant circulating CD4+ subset whose HLA-DR positivity increases with disease progression and whose V beta repertoire is similar to that of CD4+ CD38- T-cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;77:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(95)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deeks SG, et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104:942–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kestens L, et al. Selective increase of activation antigens HLA-DR and CD38 on CD4+ CD45RO+ T lymphocytes during HIV-1 infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95:436–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb07015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giorgi JV, et al. Shorter survival in advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is more closely associated with T lymphocyte activation than with plasma virus burden or virus chemokine coreceptor usage. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:859–870. doi: 10.1086/314660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chomont N, et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat Med. 2009;15:893–900. doi: 10.1038/nm.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gosselin A, et al. Peripheral blood CCR4+CCR6+ and CXCR3+CCR6+CD4+ T cells are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2010;184:1604–1616. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Addo MM, et al. Fully differentiated HIV-1 specific CD8+ T effector cells are more frequently detectable in controlled than in progressive HIV-1 infection. PLoS One. 2007;2:e321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fritsch RD, et al. Stepwise differentiation of CD4 memory T cells defined by expression of CCR7 and CD27. J Immunol. 2005;175:6489–6497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amyes E, et al. Characterization of the CD4+ T cell response to Epstein-Barr virus during primary and persistent infection. J Exp Med. 2003;198:903–911. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cotton MF, et al. Apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated immediately ex vivo correlates with disease severity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:656–664. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199711000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gougeon ML, et al. Programmed cell death in peripheral lymphocytes from HIV-infected persons: Increased susceptibility to apoptosis of CD4 and CD8 T cells correlates with lymphocyte activation and with disease progression. J Immunol. 1996;156:3509–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Grevenynghe J, et al. Transcription factor FOXO3a controls the persistence of memory CD4(+) T cells during HIV infection. Nat Med. 2008;14:266–274. doi: 10.1038/nm1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doitsh G, et al. Abortive HIV infection mediates CD4 T cell depletion and inflammation in human lymphoid tissue. Cell. 2010;143:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen HY, Di Mascio M, Perelson AS, Ho DD, Zhang L. Determination of virus burst size in vivo using a single-cycle SIV in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19079–19084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707449104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: Virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science. 1996;271:1582–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wodarz D, Nowak MA. Mathematical models of HIV pathogenesis and treatment. Bioessays. 2002;24:1178–1187. doi: 10.1002/bies.10196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dimitrov DS, et al. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J Virol. 1993;67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2182-2190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Little SJ, McLean AR, Spina CA, Richman DD, Havlir DV. Viral dynamics of acute HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 1999;190:841–850. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giorgi JV, et al. Elevated levels of CD38+ CD8+ T cells in HIV infection add to the prognostic value of low CD4+ T cell levels: Results of 6 years of follow-up. The Los Angeles Center, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:904–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z, et al. Elevated CD38 antigen expression on CD8+ T cells is a stronger marker for the risk of chronic HIV disease progression to AIDS and death in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study than CD4+ cell count, soluble immune activation markers, or combinations of HLA-DR and CD38 expression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;16:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douek DC, Roederer M, Koup RA. Emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of AIDS. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:471–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041807.123549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray JL, et al. Rab9 GTPase is required for replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, filoviruses, and measles virus. J Virol. 2005;79:11742–11751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11742-11751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garrus JE, et al. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell. 2001;107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Migueles SA, et al. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity. 2008;29:1009–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shan L, et al. Influence of host gene transcription level and orientation on HIV-1 latency in a primary-cell model. J Virol. 2011;85:5384–5393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lopez-Vergès S, et al. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14947–14952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602941103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang H, et al. Novel single-cell-level phenotypic assay for residual drug susceptibility and reduced replication capacity of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2004;78:1718–1729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1718-1729.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]