Abstract

We measure the deceleration of liquid nitrogen drops floating at the surface of a liquid bath. On water, the friction force is found to be about 10 to 100 times larger than on a solid substrate, which is shown to arise from wave resistance. We investigate the influence of the bath viscosity and show that the dissipation decreases as the viscosity is increased, owing to wave damping. The measured resistance is well predicted by a model imposing a vertical force (i.e., the drop weight) on a finite area, as long as the wake can be considered stationary.

Keywords: capillary waves, Leidenfrost effect

The drag on floating bodies has three main contributions (1): skin friction, inertial drag associated with vortex emission, and wave drag. In experiments, extracting each contribution from a global drag measurement is often difficult (2, 3). In the special case of hovercrafts, wave drag plays the major role and its magnitude has been determined by ref. 4. For a large vessel, surface waves are dominated by gravity and the author shows that the drag scales as  (S is the area of the cushion and p is the pressure under the hovercraft), and it reaches a maximum for a Froude number

(S is the area of the cushion and p is the pressure under the hovercraft), and it reaches a maximum for a Froude number  close to unity (V is the hovercraft speed). Here, we study capillary hovercrafts made of liquid nitrogen drops floating in a Leidenfrost state on the surface of water.

close to unity (V is the hovercraft speed). Here, we study capillary hovercrafts made of liquid nitrogen drops floating in a Leidenfrost state on the surface of water.

Leidenfrost drops are usually created when a liquid is deposited on a plate hot enough to induce a strong evaporation (e.g., water on a plate at 250 °C), leading to the formation of a vapor layer between the drop and the plate (5, 6). This vapor film, of thickness between 10 and 100 μm, insulates the drop, allowing lifetimes as long as 1 min for millimetric drops (7). It also dramatically reduces the friction on the drop in this perfectly nonwetting situation. Here we study Leidenfrost drops sliding on a liquid surface and investigate the role of surface deformation on friction.

Experimental Setup

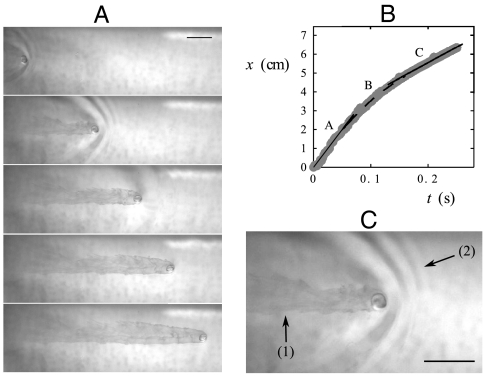

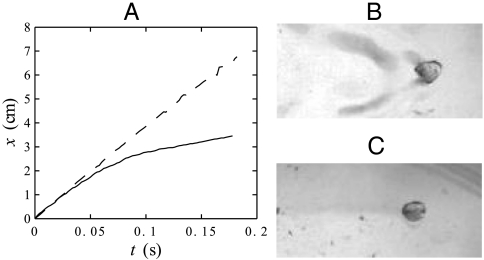

We use millimetric liquid nitrogen drops—in a Leidenfrost state at ambient temperature—arriving with some prescribed velocity onto a bath of water or silicone oil of density ρ, surface tension γ, and kinematic viscosity ν (Fig. 1). Using a fast video camera, we record the drop motion from above. A typical sequence is shown in Fig. 2A for a drop of diameter D ≈ 3 mm. Its radius is then comparable to the capillary length for liquid nitrogen  (γn = 8.8 mN/m and ρn = 808 kg/m3 are liquid nitrogen’s surface tension and density). From the images, we measure the position x of the drop as a function of time t (Fig. 2B). First, we note that the duration of an experiment is less than 1 s, much smaller than the typical 1-min evaporation time of the drop: The drop volume remains almost constant, contrasting with other recent experiments made with nitrogen drops on liquids (8). Second, the curve is smooth, despite the fact that experimentally some shape oscillations of the drop can be observed in the recorded videos. The amplitude of these oscillations does not vary much during the duration of an experiment, viscous dissipation within the drop taking place on a much longer time (of order D2/νn ≈ 50 s with νn ≈ 2·10-7 m2/s the kinematic viscosity of liquid nitrogen). Third, we observe that x changes with time in a rather unusual way. At short time (t < 0.05 s) and long time (t > 0.18 s), the drop motion is nearly uniform, as indicated by straight lines A and C in Fig. 2B, of slopes 40 cm/s and 17 cm/s, respectively. Between these two regimes, the drop clearly slows down with a typical deceleration of 170 cm/s2 as shown by line B in Fig. 2B. We repeat similar second-order polynomial fits (x = α2t2 + α1t + α0) on pieces of different trajectories (t1 < t < t2), which allows us to measure the deceleration

(γn = 8.8 mN/m and ρn = 808 kg/m3 are liquid nitrogen’s surface tension and density). From the images, we measure the position x of the drop as a function of time t (Fig. 2B). First, we note that the duration of an experiment is less than 1 s, much smaller than the typical 1-min evaporation time of the drop: The drop volume remains almost constant, contrasting with other recent experiments made with nitrogen drops on liquids (8). Second, the curve is smooth, despite the fact that experimentally some shape oscillations of the drop can be observed in the recorded videos. The amplitude of these oscillations does not vary much during the duration of an experiment, viscous dissipation within the drop taking place on a much longer time (of order D2/νn ≈ 50 s with νn ≈ 2·10-7 m2/s the kinematic viscosity of liquid nitrogen). Third, we observe that x changes with time in a rather unusual way. At short time (t < 0.05 s) and long time (t > 0.18 s), the drop motion is nearly uniform, as indicated by straight lines A and C in Fig. 2B, of slopes 40 cm/s and 17 cm/s, respectively. Between these two regimes, the drop clearly slows down with a typical deceleration of 170 cm/s2 as shown by line B in Fig. 2B. We repeat similar second-order polynomial fits (x = α2t2 + α1t + α0) on pieces of different trajectories (t1 < t < t2), which allows us to measure the deceleration  for an average velocity V = α2(t1 + t2) + α1. The results are shown in Fig. 3, where we present a series of data for Γ(V) for D ≈ 3 mm. We compare these measurements (solid symbols) to the deceleration on a solid plate (hollow symbols). The velocity dependence of the deceleration on a solid substrate is roughly linear, as suggested by the dotted line in Fig. 3; this friction can be due to dissipation in the vapor film or in the surrounding air, which should also exist for a drop moving on a liquid surface. However, we observe in the latter case a complex behavior, which corresponds to the trajectory of Fig. 2B.

for an average velocity V = α2(t1 + t2) + α1. The results are shown in Fig. 3, where we present a series of data for Γ(V) for D ≈ 3 mm. We compare these measurements (solid symbols) to the deceleration on a solid plate (hollow symbols). The velocity dependence of the deceleration on a solid substrate is roughly linear, as suggested by the dotted line in Fig. 3; this friction can be due to dissipation in the vapor film or in the surrounding air, which should also exist for a drop moving on a liquid surface. However, we observe in the latter case a complex behavior, which corresponds to the trajectory of Fig. 2B.

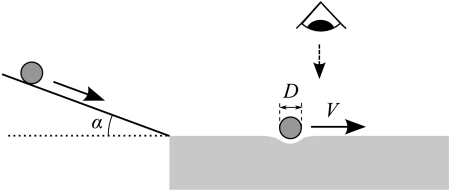

Fig. 1.

Sketch of the experiment: a liquid nitrogen drop of diameter D is thrown tangentially onto a liquid bath and filmed from above. The initial velocity is selected by the slope α of the solid plate used to throw the drop.

Fig. 2.

(A) Successive top views of a liquid nitrogen drop sliding on water. The drop diameter is D ≈ 3 mm, and its initial velocity is 40 cm/s. The interval between two images is 80 ms. (B) Position x of the same drop, as a function of time t. Straight lines A and C correspond to a velocity of 40 cm/s and 17 cm/s, respectively. Line B is a second-order polynomial fit, corresponding to a deceleration of approximately 170 cm/s2. (C) A closeup of the drop moving at a velocity V ≈ 25 cm/s. Note the two wakes for the drop (1) in the air due to water condensation and (2) at the surface of water. Scale bars in A and C correspond to 1 cm.

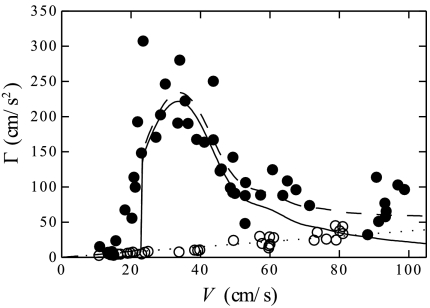

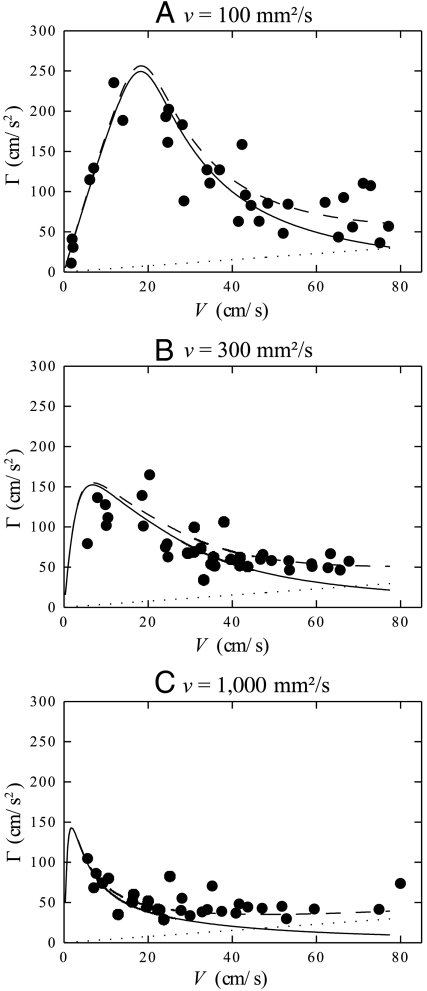

Fig. 3.

Deceleration Γ of a Leidenfrost drop of diameter D = 3.00 ± 0.25 mm moving at a velocity V on a solid (open circle) or on a water surface (solid circle). The solid line shows the prediction of wave resistance theory (expressed in Eq. 1 and calculated for a diameter D = 3.2 mm). The dotted line is a linear fit to the data on a solid and estimates the other frictional effects (dissipation in the underlying vapor film and in the surrounding air). The dashed line is the superposition of the prediction of Eq. 1 and the other frictional effects mentioned above.

First, the deceleration on water is much higher than on a solid. For V ≈ 40 cm/s, Γ is as low as 10 ± 1 cm/s2 on a solid (two orders of magnitude smaller than the acceleration due to gravity g), whereas it is 200 ± 50 cm/s2 on water. Second, for drops on the water bath, one can notice a sharp increase of the drag between V = 15 and V = 25 cm/s (Γ is then multiplied by 30). For higher velocities, the drag slowly decreases, contrasting with the measurements on a solid.

Wave Resistance

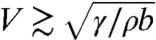

The sharp increase in the drag around 20 cm/s suggests that the measured friction results from wave resistance (9, 10). When a drop moves at a constant velocity V on the surface of water, it generates a stationary wake of capillary–gravity waves, provided that V > cmin = (4gγ/ρ)1/4 (11). This wake can be seen in the magnified view of the moving nitrogen drop in Fig. 2C. For water, with ρ = 103 kg/m3 and γ = 72 mN/m, we have cmin ≈ 23 cm/s. When V > cmin, the waves carry away energy from the moving drop, which results in an additional drag. This is the so-called wave resistance, well known for objects larger than the capillary length  (2.7 mm for water), yet modified here by the influence of surface tension (12).

(2.7 mm for water), yet modified here by the influence of surface tension (12).

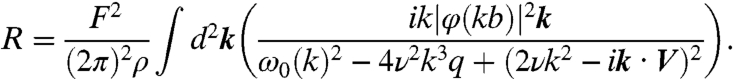

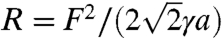

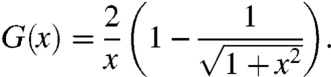

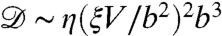

More quantitatively, we can compare these results to a model proposed by Raphaël and de Gennes where the object is replaced by a pressure field moving at a constant velocity at the fluid surface (9). Here we assume the applied pressure is uniform on a circle of radius b: The Fourier transform of the pressure field is F.φ(kb) with F the imposed vertical force and φ(kb) = 2J1(kb)/(kb) where J1 denotes the first order Bessel function of the first kind. In the case of a viscous fluid, the wave resistance is given by (13)

|

[1] |

In this expression, q2 = k2 - iV·k/ν, and ω0(k)2 = gk + γk3/ρ is the capillary–gravity wave dispersion relation in the deepwater approximation. In our experiments, the liquid tank is a few centimeters deep, larger than the millimetric wavelengths of the wake created by the drop (visible in Fig. 2C). Both F and b are related to the drop size. In particular, F is the drop weight* (between 10 and 100 μN) and b is the vapor film radius. To estimate these parameters from the measurement of the outer diameter of the (deformed) drops, we have calculated the shapes of nonwetting drops on a solid plate and deduced the drop weight F. We also assumed that the contact area of the nonwetting drop corresponds to the circle of radius b.

Eq. 1 was studied extensively by Raphaël and de Gennes in the limit ν → 0 (9). In this inviscid regime, one expects no wave resistance below cmin. At cmin, they predict a discontinuity of the wave resistance equal to  for objects much smaller than the capillary length—as for real hovercrafts, the wave drag varies as the square of the vertical force (4). For objects of finite size, but still in the limit b < a, interferences between waves emitted from different points of the drop/liquid interface lead to a suppression of the wave resistance for

for objects much smaller than the capillary length—as for real hovercrafts, the wave drag varies as the square of the vertical force (4). For objects of finite size, but still in the limit b < a, interferences between waves emitted from different points of the drop/liquid interface lead to a suppression of the wave resistance for  (or equivalently

(or equivalently  ) (9): Small bodies undergo a maximum resistance for

) (9): Small bodies undergo a maximum resistance for  of order one, a capillary analogue of the Froude number. This peak wave resistance might account for the swimming velocities chosen by some floating insects (14, 15).

of order one, a capillary analogue of the Froude number. This peak wave resistance might account for the swimming velocities chosen by some floating insects (14, 15).

This behavior is consistent with our observations: For low velocities (V < 15 cm/s), the friction is weak and comparable to that on a solid, but it sharply increases in the vicinity of V ≈ 23 cm/s. Fig. 3 shows that the data for D = 3.00 ± 0.25 mm are well fitted by the drag calculated for a 3.2-mm drop. This small difference in diameter is not surprising, because the calculation of the drop shape, neglecting the substrate deformability, underestimates the weight and the apparent contact area (16). The estimated deceleration is even closer to the data if we take into account the dissipation in the vapor film and in the surrounding air. For 3-mm drops, these frictional effects are simply estimated from a linear fit of the deceleration on the solid plate (dotted line in Fig. 3).

Our experiment, where we prevent penetration of the underlying bath by the sliding object, thus appears to be a model system for isolating the wave component of the friction. In addition, the measured wave resistance is well described by Eq. 1, contrasting with previous measurements where resistance was measured on an immersed object (17–19): For instance, for an object immersed at constant depth, the resistance discontinuity at V = cmin vanishes (13). In our experimental setup, the absence of vertical motion of the drop implies that F simply is the weight of the drop.

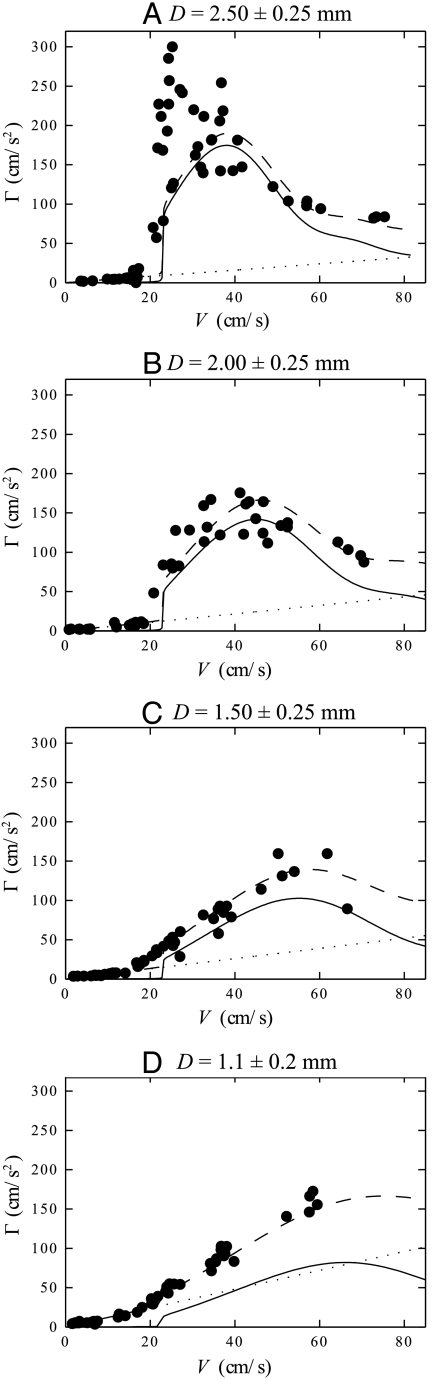

In Fig. 4, we keep the same underlying liquid (water), whereas the diameter of the drop is decreased from D = 2.5 mm (Fig. 4A) to D = 1.1 mm (Fig. 4D). For each diameter, we compare the data to Eq. 1. We also estimate the deceleration due to the vapor film and the surrounding air, extrapolating from a linear fit of the low velocity measurements (V < 20 cm/s) (dotted lines). This contribution can be summed with the prediction of Eq. 1, to give the dashed curves.

Fig. 4.

Influence of drop diameter D on the deceleration Γ(V). The solid line shows the theoretical predictions (calculated for D = 2.5 mm, 2.1 mm, 1.5 mm, and 1.3 mm, respectively). The dotted line indicates an estimation of dissipation in the vapor film and the surrounding air, extrapolated from a linear fit on the low velocity measurements (V < 20 cm/s). The dashed line is a superposition of wave resistance and these other frictional effects.

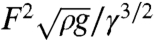

Figs. 3 and 4 show that the influence of the diameter D also supports the wave resistance scenario. First, the vertical force F increases with D: The maximum deceleration increases from 150 to 250 cm/s2 as D is multiplied by 2, from 1.5 mm (Fig. 4C) to 3 mm (Fig. 3). Eq. 1 predicts that the resistance should be proportional to the square of the drop weight F: The amplitude of the waves is expected to be proportional to F, and the resistance scales like the energy radiated away, varying as the square of the amplitude (9). One then expects the deceleration to be linear with the drop mass. This implies a very strong sensitivity to the diameter D, as the mass should scale as D3 for small drops (D ≪ an) and as D2 for larger drops. As a consequence, down to D = 1.5 mm, it appears that most of the drag is due to wave resistance. However, for the smallest drop (D = 1.1 mm, Fig. 4D), wave resistance becomes of the order of the other frictional effects.

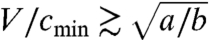

Second, the deformed area, of extension b, increases with D. According to Eq. 1, wave resistance should reach a maximum for  , a decreasing function of D. In Figs. 3 and 4, we indeed observe that the velocity corresponding to the maximum deceleration decreases as D increases: The maximum is observed for V ≈ 50 cm/s for D = 1.5 mm (Fig. 4C) and for V ≈ 30 cm/s for D = 3 mm (Fig. 3).

, a decreasing function of D. In Figs. 3 and 4, we indeed observe that the velocity corresponding to the maximum deceleration decreases as D increases: The maximum is observed for V ≈ 50 cm/s for D = 1.5 mm (Fig. 4C) and for V ≈ 30 cm/s for D = 3 mm (Fig. 3).

The magnitude of the peak velocity is also consistent with Eq. 1 because  for b ≈ 1 mm. Finally, as a consequence of both finite size and vertical force influence, the sharp increase of Γ with V seen in Fig. 3 (D ≈ 3 mm) disappears when D ≈ 1 mm (Fig. 4D).

for b ≈ 1 mm. Finally, as a consequence of both finite size and vertical force influence, the sharp increase of Γ with V seen in Fig. 3 (D ≈ 3 mm) disappears when D ≈ 1 mm (Fig. 4D).

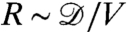

Viscous Liquids

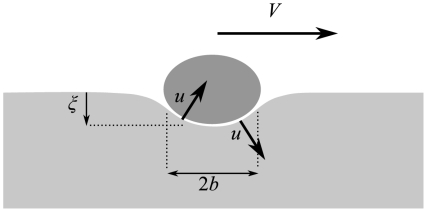

We also investigated the influence of the bath deformability by performing experiments with drops of fixed diameter D ≈ 3 mm on silicone oils of various viscosities, ranging from ν = 5 mm2/s to ν = 1,000 mm2/s. On such liquids, we have γ ≈ 20 mN/m and ρ ≈ 970 kg/m3, so that a ≈ 1.5 mm and cmin ≈ 17 cm/s. In Fig. 5A, we report two trajectories for the same initial velocity (40 cm/s) and for the two extreme viscosities (ν = 5 and 1,000 mm2/s). We clearly observe that the deceleration is much lower on the more viscous oil: The traveled distance is about twice as large. This is due to the fact that wave resistance vanishes if viscous effects dominate inertia, i.e., when the damping rate ν/λ2 is higher than the propagation rate V/λ. This occurs for ν > λV ∼ acmin ∼ 300 mm2/s. Indeed, no waves are observed on the more viscous oil (Fig. 5C, to be compared to Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

(A) Position x as a function of time t for a liquid nitrogen drop on silicone oils. The two lines correspond to two different viscosities: ν = 5 mm2/s (solid line) and ν = 1,000 mm2/s (dashed line). The drop diameter is kept constant (D ≈ 3 mm), and the initial velocity is 40 cm/s. (B and C) Close view of the same drop: (B) ν = 5 mm2/s and V ≈ 30 cm/s; (C) ν = 1,000 mm2/s and V ≈ 40 cm/s.

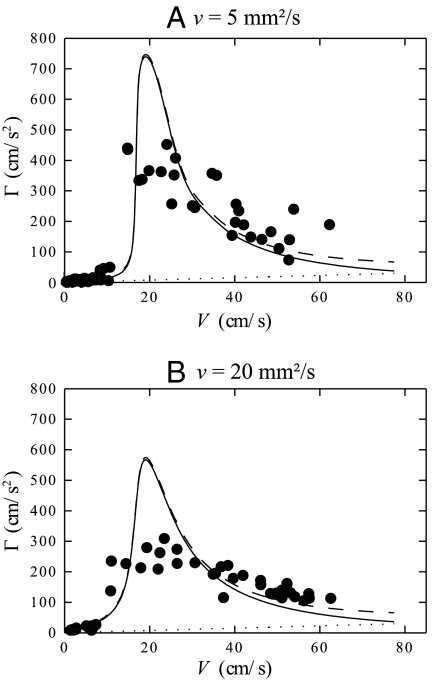

Fig. 6 shows the deceleration curves Γ(V) on the viscous oils (ν = 100, 300, and 1,000 mm2/s). We present here both experimental and theoretical results, because Eq. 1 also predicts the resistance due to the bath for higher viscosity liquids, a case not considered in ref. 9. The agreement between theory and experiments stills holds on these viscous liquids.

Fig. 6.

Deceleration Γ(V) on viscous silicone oils for D = 3.0 ± 0.5 mm. The markers show experimental results, the solid line is for the theoretical prediction (calculated for D = 3 mm), and the dashed line also includes other frictional effects, deduced from the deceleration measured on a solid (Fig. 3) and shown by the dotted line.

In the limit of small objects (b ≪ a) and large viscosities (ν≫Vb), Eq. 1 can be rewritten in the explicit form

|

[2] |

where Ca = ηV/γ is the capillary number (with η = ρν) and

|

[3] |

Even if Eq. 2 is valid only for b ≪ a, it captures the main features of the deceleration curves shown in Fig. 6, for which b ∼ a. More precisely, Eq. 3 has two limits: G(x) ∼ x at small x, and G(x) ∼ 1/x at large x. These limits correspond to two scaling laws for Eq. 2, at small and large capillary numbers (i.e., velocities smaller or larger than γ/η), which can be understood as follows.

The friction is due to viscous dissipation in the bulk. Because of the stress boundary condition on the free surface, no shear is exerted here and the main velocity gradient is extensional: As it moves at a velocity V, a drop both pushes (at the front) and pulls (at the rear) the liquid at the deformed interface (Fig. 7). If ξ is the depth of the deformation, the fluid velocity normal to the interface is (ξ/b)V, and the velocity gradient normal to the surface is (ξ/b)V/b. The volume of moving fluid scales as b3, so the viscous dissipation is  . Thus, the viscous horizontal resistance

. Thus, the viscous horizontal resistance  scales as (ξ/b)2ηVb.

scales as (ξ/b)2ηVb.

Fig. 7.

Sketch of the drop moving on a viscous liquid. The interface is deformed over the extension b and on a depth ξ. When moving at the velocity V, the drop both pulls and pushes the liquid perpendicularly to the interface, at a velocity u ∼ (ξ/b)V, which generates a viscous horizontal resistance (ξ/b)2ηVb.

It should be noted that the value of ξ depends on how fast the drop moves. The depth derives from a competition between the weight F, the viscous vertical resistance  , and, for a small object b ≪ a, the capillary force. As the drop falls into the liquid, the fluid surface increases by a quantity ξ2, which results into the capillary restoring force γξ. The falling viscous time therefore scales as ηb/γ and has to be compared to the advection time b/V. The two times are equal for V ∼ γ/η, which explains the Ca dependency of Eq. 2.

, and, for a small object b ≪ a, the capillary force. As the drop falls into the liquid, the fluid surface increases by a quantity ξ2, which results into the capillary restoring force γξ. The falling viscous time therefore scales as ηb/γ and has to be compared to the advection time b/V. The two times are equal for V ∼ γ/η, which explains the Ca dependency of Eq. 2.

At low velocities (V < γ/η), ξ reaches the equilibrium depth F/γ and the friction can be rewritten R ∼ (F/(γb))2ηVb. In Fig. 6A, we indeed see that the measured deceleration increases linearly with V. Theoretical curves in Fig. 6 also show that this linear variation becomes sharper if the bath is more viscous.

At high velocities (V > γ/η), ξ is determined by the competition between the imposed vertical force and the viscous vertical resistance: ξ ∼ falling velocity × advection time ∼ (F/(ηb))(b/V) ∼ F/(ηV). The faster the drop slides, the weaker the deformation is, so that the viscous force decreases with V: R ∼ F2/(ηVb). This explains why Γ decreases at large V in Fig. 6, for a reason that is very different from the low-viscosity mechanism. In this regime, the friction is proportional to 1/η: The more viscous the substrate, the less frictional it is.

The maximum friction occurs for V ∼ γ/η. This velocity is independent of the drop size, because waves and interferences do not play any role in this viscous regime. For ν = 100 mm2/s, we find γ/η ≈ 20 cm/s, close to the value for which the deceleration is maximum in Fig. 6A. We also expect the maximum force, scaling as F2/(γb), to be independent of the viscosity η. The theoretical curves of Fig. 6, corresponding to increasing bath viscosities, show that the maximum Γ occurs for a decreasing velocity V but tends to a constant value of the order of 150 cm/s2.

In Fig. 8, we show both experimental and theoretical results for drops sliding on the two least viscous oils, ν = 5 and 20 mm2/s. In this case, we observe a discrepancy between the data and the model. The predicted deceleration is higher than observed, which we understand as follows: The surface tension of silicone oil is about three times lower than the tension of water. Therefore, the expected wave resistance, scaling as  at V = cmin (9), is higher on oil than on water. If the deceleration due to waves becomes large, the calculation assuming a steady wake does not hold. Transient effects should be taken into account when the deceleration rate is higher than the propagation rate Γ/V > V/λ, that is, when

at V = cmin (9), is higher on oil than on water. If the deceleration due to waves becomes large, the calculation assuming a steady wake does not hold. Transient effects should be taken into account when the deceleration rate is higher than the propagation rate Γ/V > V/λ, that is, when  . This might explain the disagreement between the prediction and experiments when Γ becomes larger than 300 cm/s2 ∼ g/3.

. This might explain the disagreement between the prediction and experiments when Γ becomes larger than 300 cm/s2 ∼ g/3.

Fig. 8.

Deceleration Γ(V) for D = 3.0 ± 0.5 mm on silicone oil baths of low viscosity ν. The markers show experimental results, the solid line is for the theoretical prediction (calculated for D = 3 mm), and the dashed line also includes other frictional effects, deduced from the deceleration measured on a solid (Fig. 3) and shown by the dotted line.

Conclusion

We showed that small levitating objects moving on a liquid are mainly decelerated by the production of waves along the direction of motion. This model system allowed us to specify a few unusual properties of this special friction: (i) negligible resistance below a critical velocity (of order 20 cm/s); (ii) sharp increase (quasidiscontinuity) of the resistance above this velocity; (iii) decrease of the friction with V at large velocity; (iv) decrease of the friction as the bath is made more viscous, a consequence of wave damping. However, the low velocity regime remains to be understood, including the interaction among the vapor layer, the surrounding air, and the drop movement. In addition, the wake created by the moving drop could be characterized, using recently developed tools for measuring liquid surface deformations (20, 21). The theoretical description of wave resistance might also be improved, by a more precise description of the deformation of the drop/liquid interface (16), and by taking into account transient effects (22) in this decelerated motion.

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank A. Grier for a careful reading of the manuscript. F.C. acknowledges support from Institut Universitaire de France.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*The vapor thrust also acts on the surface, but its contribution ρvu2b2 ≈ 10-4 μN is negligible (ρv is the vapor density and the ejection velocity is u ≈ 1 cm/s as deduced from evaporation duration).

References

- 1.Faltinsen OM. Hydrodynamics of High-Speed Marine Vehicles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman RB. Hydrodynamic design of semisubmerged ships. J Basic Eng ASME. 1972;94:874–884. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suter R, Rosenberg O, Loeb S, Long H. Locomotion on the water surface: propulsive mechanisms of the fisher spider. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:2523–2538. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.19.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barratt MJ. The wave drag of a Hovercraft. J Fluid Mech. 1965;22:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leidenfrost JG. 1756. De Aquae Communis Nonnullis Qualitatibus Tractatus [A Tract About Some Qualities of Common Water]. Duisburg, in Latin.

- 6.Gottfried BS, Lee CJ, Bell KJ. The Leidenfrost phenomenon: Film boiling of liquid droplets on a flat plate. Int J Heat Mass Transfer. 1966;9:1167–1187. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biance A-L, Clanet C, Quéré D. Leidenfrost drops. Phys Fluids. 2003;15:1632–1637. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snezhko A, Ben Jacob E, Aranson IS. Pulsating–gliding transition in the dynamics of levitating liquid nitrogen droplets. New J Phys. 2008;10:043034. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raphaël E, de Gennes P-G. Capillary gravity waves caused by a moving disturbance: Wave resistance. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 1996;53:3448–3455. doi: 10.1103/physreve.53.3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun S-M, Keller JB. Capillary-gravity wave drag. Phys Fluids. 2001;13:2146–2151. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson W. Ripples and waves. Nature. 1871;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lighthill MJ. Waves in Fluids. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chevy F, Raphaël E. Capillary gravity waves: A “fixed-depth” analysis. Europhys Lett. 2003;61:796. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bush JWM, Hu DL. Walking on water: Biolocomotion at the interface. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2006;38:339–369. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voise J, Casas J. The management of fluid and wave resistances by whirligig beetles. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:343–352. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Princen HM, Mason SG. Shape of a fluid drop at a fluid-liquid interface II. Theory for three-phase systems. J Colloid Sci. 1965;20:246–266. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Browaeys J, Bacri J-C, Perzynski R, Shliomis MI. Capillary-gravity wave resistance in ordinary and magnetic fluids. Europhys Lett. 2001;53:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burghelea T, Steinberg V. Onset of wave drag due to generation of capillary-gravity waves by a moving object as a critical phenomenon. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;86:2557–2560. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burghelea T, Steinberg V. Wave drag due to generation of capillary-gravity surface waves. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2002;66:051204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.66.051204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moisy F, Rabaud M, Salsac K. A synthetic Schlieren method for the measurement of the topography of a liquid interface. Exp Fluids. 2010;46:1021–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobelli PJ, Maurel A, Pagneux V, Petitjeans P. Global measurement of water waves by Fourier transform profilometry. Exp Fluids. 2010;46:1037–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Closa F, Chepelianskii A, Raphaël E. Capillary-gravity waves generated by a sudden object motion. Phys Fluids. 2010;22:052107. [Google Scholar]