Abstract

Cellular energy metabolism, survival and death are controlled by mitochondrial calcium signals originating in the cytoplasm. Now, RNAi studies link three proteins — MICU1, NCLX and LETM1 — to the previously unknown molecular mechanism of mitochondrial calcium transport.

Twenty years ago, mitochondria were viewed as cellular power plants, regulated solely by substrates. Nowadays, mitochondria are also considered as nodes of signalling pathways that engage a variety of effector mechanisms to control the cell’s life. A key factor in this advance was the discovery of the participation of mitochondria in calcium signalling.

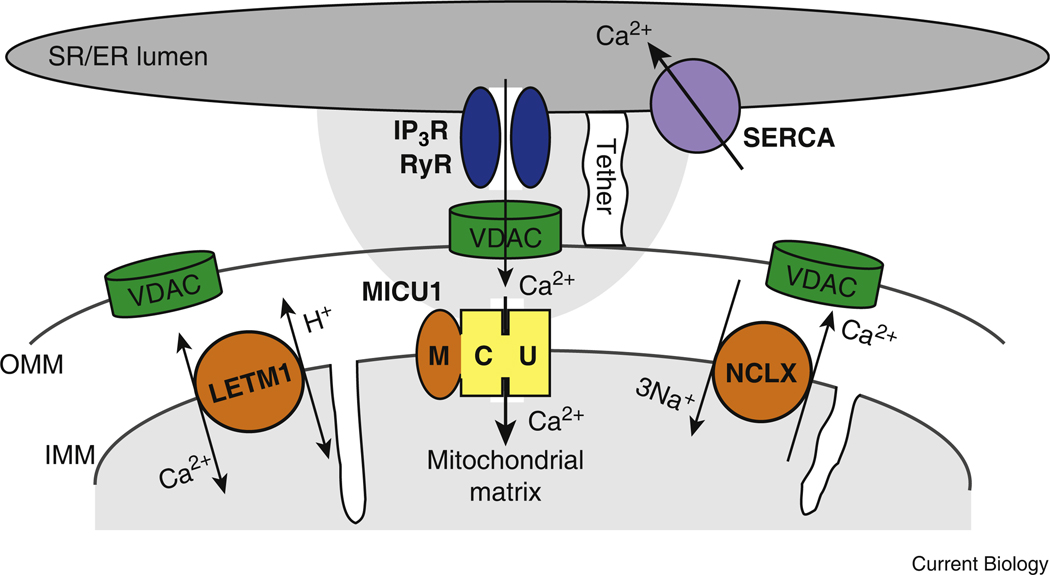

Early studies with isolated mitochondria showed the requirement for supraphysiological [Ca2+] elevations to stimulate Ca2+ uptake. Thus, it was a major surprise when the studies of Rizzuto and Pozzan and colleagues [1] revealed propagation of hormone-induced cytoplasmic [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]c) calcium signals to the mitochondrial matrix in cells [1]. They proposed that mitochondria sensed the high local [Ca2+]c in the vicinity of the open inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) rather than the substantially lower global [Ca2+]c. Very recently, this idea has been directly validated by targeting Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent proteins to the mitochondrial surface. These measurements provided evidence that mitochondria see a 10-fold higher [Ca2+]c than the global [Ca2+]c signal [2,3]. Another line of studies revealed that positioning of mitochondria close to the endoplasmic/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) is supported by interorganellar tethers (Figure 1) [4]. One proposed tether between the ER and the outer mitochondrial membrane includes the IP3R and the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC), which would provide a shortcut for the released Ca2+ to access and cross the outer mitochondrial membrane [5]. Strategic positioning of mitochondria is also facilitated dynamically by Ca2+-induced inhibition of mitochondrial movements close to the open IP3Rs/RyRs [6]. These results illustrate that cells have developed a collection of sophisticated means to ensure that mitochondria recognize Ca2+ mobilization from the ER/SR.

Figure 1. Molecular aspects of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport.

The scheme depicts the new molecules (MICU1, LETM1 and NCLX, in orange) mediating Ca2+ influx and efflux across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) at an area of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–mitochondrial association. The shades of gray represent the [Ca2+]: dark gray, 100–500 mM; white, 100 nM. SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; SERCA, sarcoplasmic ER Ca2 + ATPase; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; RyR, ryanodine receptor.

It has been known for almost 50 years that Ca2+ uptake across the inner mitochondrial membrane is mediated by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU). A patch clamp study of mitoplasts — i.e. mitochondria lacking the outer mitochondrial membrane — has provided evidence that the MCU is a highly Ca2+-selective ion channel (IMiCa) [7]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux has been attributed to exchangers that directly couple Ca2+ releaseto Na+ or H+ uptake [8]. However, the identity of the proteins mediating Ca2+ influx and efflux remained elusive. Among the early candidates for the MCU were mitochondria-localized RyR1 [9] and the uncoupling proteins UCP2/3 [10], but such a role for these proteins has yet to be confirmed by other groups and these proteins do not seem to be expressed in some tissues displaying robust MCU activity.

Over the past year, three novel candidate proteins have now been proposed to mediate Ca2+ transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Jiang et al. [11] reported the identification of LETM1 as a protein that regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ and H+ concentrations in a genome-wide Drosophila RNA interference (RNAi) screen. LETM1, previously described as a K+/H+ exchanger [12,13], was suggested to support electrogenic import of Ca2+ (one Ca2+ in for one H+ out) when the mitochondrial matrix [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]m) is low, but, when [Ca2+]m is high or the cytoplasmic pH is low, LETM1 would mediate Ca2+ export [11]. Notably, silencing of LETM1 was found to suppress the majority of the IP3R-linked [Ca2+]m signal in HeLa cells without attenuating the mitochondrial membrane potential, the major component of the driving force for the Ca2+ uptake [11]. LETM1 activity was inhibited by both ruthenium red/Ru360 and CGP37157, inhibitors of the MCU and of the exchangers that mediate mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux, respectively [11]. These results remain a subject of intense discussion because they diverge in several regards from previous studies that have reported the following: the LETM1 had been linked to K+ homeostasis; the mitochondrial H+/Ca2+ exchanger had appeared to be non-electrogenic (one Ca2+ for two H+); the loss of LETM1 had been shown to result in loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential; CGP37157 had not been seen to suppress the IP3R-linked [Ca2+]m signal; and the exchanger was not thought to be sensitive to ruthenium red.

NCLX/NCKX6 was first identified as a member of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger family in 2004. It was originally proposed to localize to the ER or to the plasma membrane [14]. However, NCLX was found to catalyze Na+- or Li+-dependent Ca2+ transport at similar rates, a distinguishing feature of the mitochondrial exchange. In a recent study, Palty et al. [15] reevaluated the subcellular distribution of NCLX and found that the endogenous protein localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane in several tissues and that overexpression of NCLX in cell lines resulted in the same localization. Mitochondrial Na+-dependent Ca2+ efflux was enhanced upon overexpression of NCLX and reduced by silencing of NCLX expression by RNAi, which could be rescued by the expression of heterologous NCLX [15]. Mitochondria-localized NCLX was inhibited by CGP37157 and showed Li+/Ca2+ exchange, further supporting NCLX as a mediator of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange [15]. Since electron microscopy showed that the NCLX immunoreactivity is spread along the cristae [15], Ca2+ efflux might occur across the entire surface of the inner mitochondrial membrane, in contrast to Ca2+ uptake, which is concentrated in foci [1–3].

In the most recent work, MICU1 has been identified as an essential element of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake [16]. Perocchi et al. [16] first selected from the mouse and human genes encoding inner mitochondrial membrane proteins the 18 genes that were found in the majority of mammalian organs and also conserved in kinetoplastids but not in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Then, they performed an RNAi screen of the top 13 candidates in HeLa cells expressing a [Ca2+]m reporter. RNAi against only one candidate, MICU1, caused significant suppression of the [Ca2+]m signal evoked by an IP3-linked agonist. MICU1 is a single-pass, transmembrane protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane, which does not seem to participate in channel pore formation. However, MICU1 has a pair of Ca2+-binding EF-hand domains, the mutation of which eliminates the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Thus, MICU1 is likely to serve as a Ca2+-sensing regulatory subunit of the MCU (Figure 1).

These results indicate that the MCU comprises distinct pore-forming and regulatory proteins. Combined with the observation that IMiCa is highly selective for Ca2+, functional relatives of the MCU seem to be the Ca2+ channels that mediate store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) and the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs). Consideration of the structure and function of these channels might offer some clues to the organization of the MCU (Table 1). SOCE involves the pore-forming ORAI subunits in the plasma membrane, which are activated upon binding to the ER membrane protein, STIM, which senses changes in ER luminal [Ca2+] by its EF hand. During ER Ca2+ release, dissociation of Ca2+ from STIM induces oligomerization, translocation to ER domains close to the plasma membrane and interaction with ORAI [17]. Thus, one might speculate about a model where Ca2+ binding to MICU1 leads to a conformational change that allows the interaction with the pore subunit of the MCU. Notably, high Ca2+ exposure leads to activation of the MCU in milliseconds, indicating that the Ca2+ effect on MICU1 is efficiently relayed to the pore. For the VDCC, a [Ca2+]c change does not trigger channel opening and the α1 subunit acts as both Ca2+ sensor and pore (Table 1) [18].

Table 1.

Location and structure of the MCU compared with STIM–ORAI and VDCC L-type channels.

| MCU (IMiCa) | STIM–ORAI | VDCC (L type) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcellular location | IMM | ORAI, PM; STIM, ER | PM |

| Subunit structure | |||

| Pore: | ? | ORAI tetramer (4 TM each) | α1 (four domains each with 6 TM) involves the voltage sensor and gating apparatus |

| Regulator: | MICU1 (1 TM)? Ca2+-dependent gating |

STIM (1 TM) Ca2+ unbinding in ER induces oligomerization, traffic to PM and gating of ORAI |

α2 + β + δ (1 TM) + γ (4 TM) shift the kinetics and voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, surface expression |

| Inhibitor | Ru360 (IC50 2 nM) RuRed (IC50 9 nM) |

La3+, Gd3+, SKF96365 or 2-APB (high µM range) | Phenylalkylamines (verapamil) Dihydropyridines (nifedipine) Benzothiazepines (diltiazem) |

The transient receptor potential (TRP) V5 and V6 channels are not shown in the table because they lack a discrete regulatory subunit. However, these channels are also highly Ca2+ selective and display several functional similarities to the IMiCa. IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TM, transmembrane domain.

The Ca2+ selectivity is high for all three channels, but the order of divalents is different for IMiCa (Ca2+ ≈ Sr2+ ≫ Mn2+ ≈ Ba2+) compared with STIM–ORAI and the VDCC (Ba2+ > Sr2+ > Ca2+). The blocking affinity of Ca2+ for monovalents is three to four orders higher for IMiCa (2 nM) than for STIM–ORAI and VDCC (20 µM and 1 µM), which may be relevant because the [Ca2+]c surrounding the MCU is lower than the millimolar extracellular [Ca2+] to which ORAI and VDCC are exposed. The unitary conductance of the MCU is similar to that of the VDCC (pS) and much higher than the fS conductance of ORAI. A distinctive feature of the IMiCa is the lack of Ca2+-induced inactivation ([7], but see [19]). The Ca2+-induced inhibition and facilitation are mediated through calmodulin at least in part for both STIM–ORAI and VDCC. A calmodulin-binding domain has not been identified on MICU1 but evidence for Ca2+–calmodulin-mediated facilitation has been presented for the MCU [19,20]. The IMiCa is voltage dependent like the VDCC. Interestingly, it is activated by hyperpolarization, like the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (HCN). Finally, the MCU, STIM–ORAI and VDCC display different pharmacological profiles (Table 1). Thus, striking similarities exist between the MCU and STIM–ORAI or VDCC structure and function, but the MCU has its unique fingerprint.

In MICU1-deficient cells, lower resting [Ca2+]m was observed [16]. This result indicates that some mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was active at ≈ 100 nM [Ca2+]c. Indeed, ruthenium red-sensitive and low [Ca2+]c-activated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanisms have been described earlier (e.g. rapid uptake mode) [8]. Thus, MICU1 might confer Ca2+ sensitivity to multiple pores at distinct [Ca2+]c concentrations or to a single pore at multiple [Ca2+]c concentrations, depending on the regulatory inputs (e.g. posttranslational modification). In any case, analysis of the proteins that partner MICU1 will provide insight into the remaining mystery of the MCU.

References

- 1.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science. 1993;262:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.8235595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giacomello M, Drago I, Bortolozzi M, Scorzeto M, Gianelle A, Pizzo P, Pozzan T. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csordas G, Varnai P, Golenar T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, Balla T, Hajnoczky G. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csordas G, Renken C, Varnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnoczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szabadkai G, Bianchi K, Varnai P, De Stefani D, Wieckowski MR, Cavagna D, Nagy AI, Balla T, Rizzuto R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:901–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi M, Weaver D, Hajnoczky G. Control of mitochondrial motility and distribution by the calcium signal: a homeostatic circuit. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:661–672. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunter TE, Sheu SS. Characteristics and possible functions of mitochondrial Ca(2+) transport mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1291–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beutner G, Sharma VK, Lin L, Ryu SY, Dirksen RT, Sheu SS. Type 1 ryanodine receptor in cardiac mitochondria: Transducer of excitation-metabolism coupling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1717:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trenker M, Malli R, Fertschai I, Levak-Frank S, Graier WF. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3 are fundamental for mitochondrial Ca2+ uniport. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:445–452. doi: 10.1038/ncb1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang D, Zhao L, Clapham DE. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies Letm1 as mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ antiporter. Science. 2009;326:144–147. doi: 10.1126/science.1175145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowikovsky K, Froschauer EM, Zsurka G, Samaj J, Reipert S, Kolisek M, Wiesenberger G, Schweyen RJ. The LETM1/YOL027 gene family encodes a factor of the mitochondrial K+ homeostasis with a potential role in the Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30307–30315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimmer KS, Navoni F, Casarin A, Trevisson E, Endele S, Winterpacht A, Salviati L, Scorrano L. LETM1, deleted in Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome is required for normal mitochondrial morphology and cellular viability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:201–214. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lytton J. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers: three mammalian gene families control Ca2+ transport. Biochem. J. 2007;406:365–382. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palty R, Silverman WF, Hershfinkel M, Caporale T, Sensi SL, Parnis J, Nolte C, Fishman D, Shoshan-Barmatz V, Herrmann S, et al. NCLX is an essential component of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:436–441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perocchi F, Gohil VM, Girgis HS, Bao XR, McCombs JE, Palmer AE, Mootha VK. MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca(2+) uptake. Nature. 2010;467:291–296. doi: 10.1038/nature09358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakriya M. The molecular physiology of CRAC channels. Immunol. Rev. 2009;231:88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau B, Nelson C, Parekh AB. Biphasic regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1672–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csordas G, Hajnoczky G. Plasticity of mitochondrial calcium signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42273–42282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]