Abstract

We use data from the National Health Interview Survey (2000–2006) to examine the social determinants of health insurance coverage and access to care for immigrant children by 10 global regions of birth. We find dramatic differences in the social and economic characteristics of immigrant children by region of birth. Children from Mexico and Latin America fare worse than immigrant children born in the U.S. with significantly lower incomes and little or no education. These social determinants, along with U.S. public health policies regarding new immigrants, create significant barriers to access to health insurance coverage, and increase delayed or foregone care. Uninsured immigrant children had 6.5 times higher odds of delayed care compared with insured immigrant children.

Keywords: Immigration, uninsurance, immigrant children, health access

Social determinants of health, including age, race, and poverty underlie substantial inequities in health and health care among social groups, witnessed within and across countries.1 These same social determinants affect the success and vitality of children who immigrate to the U.S. from other countries and are important for the future of these children and for the future of the U.S. Over the past decade, U.S. federal policy changes have resulted in significant barriers to needed health care by restricting access to public health insurance programs for immigrant populations. Past studies have documented that these policies increase uninsurance rates and differential access to health care for immigrant children.2–4 However, immigrant children are not a homogeneous group and determinants of health and health care may differ by the child's country of origin. In this paper, we use variables in the National Health Interview Survey that identify the global region of origin for new immigrant families in the U.S. between 2000 and 2006, health insurance coverage, as well as information on delayed and foregone health care. We use these data to examine the variation in social determinants of health care coverage and access for immigrant children by global region of birth.

We begin with an introduction of trends in immigration in the U.S. and an overview of studies that use different sources of survey data to understand the impact of immigration on health and health status. We then describe our research design and analytical methods, and conclude with a discussion of our findings and recommendations to address the social determinants of health for immigrant children to improve access to health care.

Immigration

The U.S. has a long and varied history on immigration policy. Currently, the objectives of immigration policy are to: “reunite families by: admitting immigrants who already have family members living in the United States; admitting workers in occupations with strong demand for labor; provide a refuge for people who face the risk of political, racial, or religious persecution in their home countries; and provide admission to people from a diverse set of countries.”5[p.4] The immediate relatives of U.S. citizens—spouses, parents of citizens ages 21 and older, and unmarried children under 21—are admitted to the U.S. without any limit. In 2004, immediate family members accounted for 43% of permanent immigrants' admissions, the largest single category.5

Children of immigrants are the fastest growing part of the U.S. child population. While immigrants constitute 11% of the total U.S. population, children of immigrants make up 22% of the 23.4 million children under 6 years old in the U.S. and 20% of the population ages 6 to 17.6 In addition, immigrant children account for nearly all of the growth in public school enrollment, accounting for 10.8 million school-age children in 2007.6

Immigrant children and their families tend to be poor, uninsured, and uneducated. Poverty rates for immigrants and their children (under age 18) are nearly 50% higher than rates for U.S. citizens; immigrants and their children account for 71% of the increase in the uninsured from 1989 to 2007; a key determinant of poverty and high uninsurance rates is low education levels.7 Between 2000 and 2007, 35.5% of immigrants 18 years and older had not finished high school, compared with 8% of native citizens.

Children of immigrants are more likely than others to have fair or poor health and to lack health insurance or a usual source of health care. Young low-income children of immigrants remain twice as likely to be uninsured as those of natives (22% versus 11%), despite a substantial increase in the coverage of low-income children of immigrants through Medicaid and other public programs between 1999 and 2002 (from 45% to 57%). Seven percent of young children of immigrants are reported in fair or poor health by their parents, over twice the rate for children of natives (3%). More than twice as many young children of immigrants as natives lack a usual source of health care (8% versus 3%).7

Most new immigrants to the U.S. currently come from Mexico and Central America. In 2007, Mexicans accounted for 31.3%, more than the number of immigrants from any other region of the world. If one combines categories to include Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean, immigrants from these countries accounted for 54.6% of new immigrants. East Asia/Southeast Asia (17.6%) is the region with the next largest number of immigrants.7 It is estimated that one-third of all immigrants are undocumented, with an estimated 50% of the immigrants from Mexico and Central America being undocumented.7

Data source often dictates levels of analysis

Numerous studies have addressed health disparities for immigrant children both in terms of health insurance coverage and access to care. Interestingly, the level and type of variables used to understand the complex relationship between race and ethnicity, origin of birth and years in the U.S. are largely determined by the data source that is used for the analysis. We review a few of the key survey sources by highlighting key studies and their findings.

Van Wie and her colleagues used data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) to document changes in health insurance coverage between Hispanic children and non-Hispanic children in the U.S. between 1996/97 and 2004/2005.8 They found that while expansions in public health insurance programs (namely the State Children's Health Insurance Program [CHIP]) appear to have increased health insurance coverage for Hispanic children, the disparities in coverage between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites did not improve. Control variables used in this study included two different citizenship status indicators, if the child was a citizen and if at least one adult in the household was a citizen. While the CPS has good data on country of origin and health insurance measures, it does not include measures of health care access and health care use. In the 2007 CPS, there were 149 counties of origin identified for respondents, including whether the child was born in the U.S. or not.9

Burgos et al., using data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) conducted between 1988 to 1994 by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that immigrant children born in Mexico fared worse on health status and access measures than second- or third-generation U.S.-born Mexican American children.10 Even after controlling for health insurance coverage and socioeconomic status, first-generation Mexican American children were less likely than non-Hispanic White children to have a usual source of care, to have a specific provider, or to have seen or talked with a physician in the past year. Although NHANES has unique and comprehensive health status measures, it has a limited sample size and only distinguishes among children born in the U.S., Mexico, or “elsewhere.” While it distinguishes Mexican from other Hispanic and non-Hispanic individuals, NHANES does not allow one to identify country of birth unless it is Mexico.9

Yu et al. used data from the National Health Interview Survey (1997 through 2000) and found that Asian American children do better than non-Hispanic Whites with respect to health status, use of prescription drugs, and chronic conditions.11 Yu et al.'s study also found significantly better health among non-citizen immigrant children compared with U.S.-born immigrants. Interestingly, because of data limitations, Yu and her colleagues rely on race and ethnicity as opposed to country or region of origin when examining issues of access and coverage for Asian American children. Although NHIS does include information on whether children and their parents were born in the U.S. or not, it does not include details about country of origin. The NHIS distinguishes those who are U.S.-born from those born in 10 broad global regions. Regions are identified in the NHIS public use files based on countries' geographic proximity to one another.9

Ku and Matani used data from the 1997 National Survey of America's Families (NSAF) and found that being a child of non-citizen parents reduced access to ambulatory medical care and emergency room care, controlling for health status, income, and race/ethnicity.12 For children of non-citizen parents, the access gaps are larger for non-citizen children than for citizen children, but both types of children have poorer access to medical care than children of citizens. The NSAF includes information on citizenship status, health insurance coverage, and health care use. In addition, for household members who were born outside the United States, country of origin is identified. But small sample size by country of origin limits analysis by this level of detail. The NSAF was fielded in 1997, 1999, and 2002 and unfortunately has not been continued.13

In a more recent study, using data from the 2003 National Medical Expenditure Survey (MEPS) to assess the medical expenditures of U.S.-born vs. foreign-born immigrants, Yu found that even when individuals had health insurance coverage, they used fewer services than either U.S.- born or second-generation immigrants.14 Insured immigrants had much lower medical expenses than insured U.S.-born citizens, even after the effects of insurance coverage were controlled. While more recent MEPS data do not include any immigrant status variables, the 2003 MEPS data do allow the distinction between U.S.-born and foreign-born, as well as years in the U.S.

Regions are important

The World Health Organization (WHO) has used region of the world as their unit of analysis to estimate and monitor global disease burden since the early 90s.15 In 1991 the World Bank commissioned the World Health Organization to develop a comprehensive assessment of disease, injuries, and risk factors for eight major regions of the World. The data generated from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is used to monitor trends over time and to inform priorities for research and to better target global policies and funding strategies. The WHO is in the process of updating these measures in the more recent GBD 2005 study (GBD 2005) with estimates anticipated in 2010.16

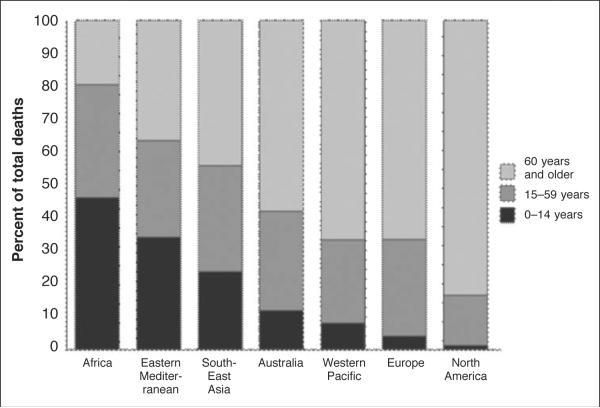

The WHO also uses region of the world to monitor morbidity and mortality for children and adults. The most recent analysis shows the vast disparities in these indices by region of the world. Figure 1 shows the 2004 mortality rate by age and region, with children from African and Eastern Mediterranean faring the worst followed by Eastern Asia.

Figure 1.

Percent distribution of age at death by region, 2004.

Source: World Health Organization: Health Statistics and Informatics Department, 2008. “Global burden of disease: 2004 update.” Selected figures and tables. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/ global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html.

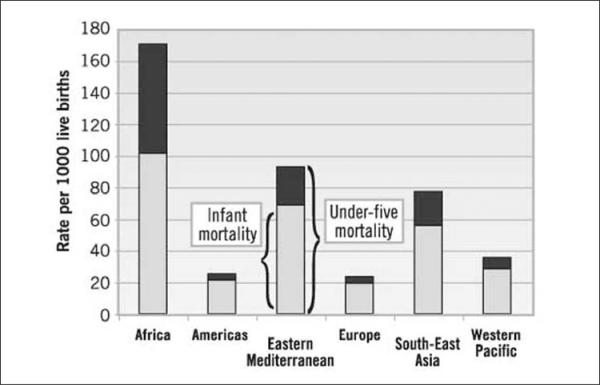

Figure 2 shows the under-five mortality rates; it, too, highlights disparities across region of the world, with children from Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean faring poorly.

Figure 2.

Under-five and infant mortality rates, by WHO Region, 2003.

Source: World Health Organization: Health Statistics and Health Information Systems, 2005. “Under-five and infant mortality rates, by WHO Region, 2003.” Maps and graphs: Health Status Statistics. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/maps_graphshealthstatus/en/index1.html.

Following in the footsteps of the WHO, we use region of birth to understand differences in health insurance coverage and access to care for immigrant children. Health policy has historically focused inward on national issues and policy. However, the increasing globalization of the world—with increasing movement of people, goods, and services across more permeable borders continues to have a complex influence on the health of individuals. In order to meet the needs of immigrant children it will be important to reorient our health policies in ways that align our national interest in improving health with the realities of a globalized world17—this means understanding the complex dynamics of regional health status, disease burden, and the inherent disparities by region for our new and growing immigrant population.

Immigrant children are not a homogeneous group, and the determinants of health and health care will differ by a child's country as well of region of origin. In order to understand how immigrant children's access to health care may differ, we examined the variation in health care coverage and access for immigrant children by global region of birth. Our analysis highlights areas that may be most affected by recent U.S. federal policy changes and provides evidence of the social determinants of barriers to health care coverage and access for immigrant children from certain global regions.

Methods

Data source and sample

This study is a population-based analysis of national survey data for children of immigrant families in the U.S. using National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2000 to 2006. The NHIS data were obtained from the Integrated Health Interview Series (IHIS), a web-based data resource (www.ihis.us)18 containing harmonized NHIS data from 1969 to the present.19 Children of immigrant families were identified as those living with at least one biological parent and for whom one or both parents were not born in the U.S. (n=54,612). Those with missing data for region of birth or any covariates (5%) were excluded, leaving an unweighted analytic sample of 51,850. Data from 2000 to 2006 were pooled to obtain a sufficient sample size for each of the geographic regions. Sampling weights were adjusted to account for pooling seven years of data.

Measures

Indicators of interest are measures of health care coverage and access to care. Health care coverage was defined as health insurance status at time of survey (insured/uninsured). Insurance types were defined by responses to the survey question, “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan?” with the follow-up question, “What kind of health insurance or health care coverage do you have?” The following insurance types were included in this analysis: private coverage (includes insurance plans obtained through the workplace, a union, or purchased directly); public coverage (includes any reports of Medicaid, Medicare, State Children's Health Insurance Plan [SCHIP]); other state-sponsored programs; other government programs; and uninsured (those that report no type of insurance coverage). Insurance types are not mutually exclusive. Respondents may have reported more than one type of insurance. Health care access was examined using two measures representing restricted access to care due to financial concerns. Delayed care was defined based on reporting that health care was delayed in the past 12 months due to cost. Foregone care was defined as health care needed but not received in the past 12 months due to cost.

Geographic regions were defined using the NHIS classification for region of birth. The regions were broadly classified according to geography: 1) United States; 2) Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and Puerto Rico; 3) South America; 4) Europe; 5) Russia; 6) Africa; 7) the Middle East; 8) the Indian subcontinent; 9) Asia; 10) Southeast Asia. Those born elsewhere or whose place of birth was unknown were excluded (see Appendix for additional details).

Additional covariates included sex, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, years in the U.S., highest parent educational attainment, parent employment, and poverty status. Sex was classified as female or male. Age was classified in groups representing 0–4 years, 5–11 years, and 12–17 years. Race was classified as White, Black, Asian or other/multiple races. Hispanic ethnicity was classified as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. Years in the U.S. was classified as less than 1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, and 10 years or more. Highest parent educational attainment for each child was classified as less than high school, a high school diploma, some college, and a college degree, with a college degree defined as the highest educational attainment of the parents. Parent employment status for each child was defined as the number of currently employed parents (0, 1, or 2). Poverty status group was defined as less than 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), 100–199% of the FPL, and 200% or more of the FPL.

Analysis

We assessed the extent to which children from different regions differed in background characteristics that may be associated with health care coverage and access using cross-tabulations and design-based F-tests to account for the complex sample design.

Controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, years in the U.S., family type, parent education, parent employment, and poverty status, we used multivariate logistic regression to estimate the odds of being uninsured for foreign-born children compared with children of immigrant families who are born in the U.S. Finally, to examine restricted access to care due to financial concerns, we estimated the odds of delayed care in the past year due to cost and the odds of foregone care in the past year due to cost with logistic regression models adjusted for characteristics of the child and of the family. In all models, U.S.-born children of immigrant families were the reference group to which foreign-born children from different regions were compared. Models were built sequentially by starting with unadjusted models, then adding characteristics of the child, then characteristics of the family. In the health care access models, insurance coverage was the final addition.

All analyses were conducted with Stata SE version 10.1, which produces unbiased estimates from data collected through complex sampling designs.20–21 Stata survey techniques properly account for the unequal probabilities of selection and the stratified/ clustered sampling design of the NHIS. Variance estimates were produced using Taylor series linearization.

Results

Bivariate analyses showed dramatic differences in the social and economic characteristics of immigrant children by global region of birth (see Table 1). For every demographic, economic, and social characteristic examined, the distributions differed significantly by region of child's birth, with the exception of sex. Most striking are the differences in social characteristics defined by parent socioeconomic indicators. For example, 60% of children born in the Mexico/Central America region live in families where no parent has a high school education. Conversely, children born in Asia or the Indian Subcontinent regions tend to have at least one college-educated parent (62% and 74%, respectively). Moreover, while 25% of all children in immigrant families live below poverty, 48% of children born in Mexico/Central America, 45% of children born in the Middle East, and 35% of children born in Africa live below poverty.

Table 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF CHILDREN IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES IN THE U.S. BY GLOBAL REGION OF BIRTH, NHIS DATA 2000–2006

| United States | Mexico or C. America | South America | Europe | Russia | Africa | Middle East | Indian Subcont. | Asia | SE Asia | Total | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample size | 42,857 | 6,143 | 709 | 450 | 219 | 259 | 158 | 289 | 293 | 473 | 51,850 | |

| Weighted population | 12,762,933 | 1,434,035 | 204,586 | 221,713 | 108,007 | 102,048 | 76,997 | 126,159 | 136,461 | 190,778 | 15,363,719 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 51% | 52% | 49% | 52% | 47% | 44% | 51% | 52% | 53% | 50% | 51% | .4724 |

| Female | 49% | 48% | 51% | 48% | 54% | 56% | 49% | 48% | 47% | 50% | 49% | |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 0–4 years | 35% | 9% | 7% | 10% | 2% | 9% | 13% | 11% | 11% | 6% | 30% | <.0001 |

| 5–11 years | 40% | 40% | 44% | 42% | 38% | 41% | 35% | 40% | 39% | 31% | 40% | |

| 12–17 years | 26% | 52% | 49% | 48% | 60% | 51% | 52% | 50% | 51% | 63% | 30% | |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White only | 69% | 80% | 82% | 91% | 98% | 28% | 91% | 5% | 7% | 9% | 69% | <.0001 |

| Black only | 9% | 8% | 6% | 4% | 0% | 70% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 9% | |

| Asian only | 14% | 1% | 3% | 4% | 2% | 0% | 9% | 93% | 90% | 89% | 15% | |

| Other or multiple race | 8% | 11% | 9% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 8% | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 55% | 93% | 86% | 4% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 0.5% | 1% | 55% | <.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic | 45% | 7% | 14% | 96% | 99% | 98% | 100% | 100% | 99.5% | 99% | 45% | |

| Years in U.S. | ||||||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 4% | 4% | 5% | 10% | 7% | 5% | 6% | 8% | 4% | 5% | <.0001 | |

| 1 year to less than 5 years | 40% | 52% | 44% | 35% | 44% | 37% | 42% | 43% | 33% | 41% | ||

| 5 years to less than 10 years; | 33% | 31% | 32% | 38% | 42% | 37% | 36% | 29% | 31% | 33% | ||

| 10 years or more | 22% | 13% | 20% | 17% | 8% | 21% | 16% | 20% | 32% | 21% | ||

| Immigrant Family Type | ||||||||||||

| Both parents foreign-born | 54% | 75% | 76% | 65% | 82% | 77% | 86% | 92% | 74% | 74% | 58% | <.0001 |

| Foreign parent, U.S. parent | 32% | 6% | 5% | 24% | 5% | 3% | 4% | 1% | 16% | 13% | 28% | |

| Foreign-born single parent | 14% | 19% | 19% | 11% | 13% | 20% | 10% | 7% | 10% | 13% | 15% | |

| Highest parent educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Less than a H.S. diploma | 29% | 60% | 18% | 6% | 14% | 9% | 20% | 8% | 9% | 22% | 31% | < .0001 |

| High school diploma | 20% | 17% | 24% | 21% | 17% | 16% | 18% | 13% | 16% | 17% | 20% | |

| Some college | 22% | 13% | 18% | 21% | 22% | 21% | 14% | 5% | 14% | 19% | 21% | |

| College degree | 28% | 9% | 40% | 52% | 48% | 54% | 49% | 74% | 62% | 42% | 28% | |

| Parent employment status | ||||||||||||

| No employed parents | 9% | 12% | 6% | 3% | 12% | 10% | 20% | 6% | 12% | 11% | 9% | < .0001 |

| 1 Employed parent | 50% | 57% | 50% | 49% | 51% | 53% | 55% | 58% | 46% | 47% | 51% | |

| 2 Employed parents | 41% | 31% | 44% | 48% | 37% | 38% | 25% | 37% | 42% | 43% | 40% | |

| Family poverty status | ||||||||||||

| <100% FPL | 23% | 48% | 25% | 11% | 30% | 35% | 45% | 18% | 15% | 26% | 25% | < .0001 |

| 100–199% FPL | 27% | 34% | 32% | 20% | 24% | 21% | 26% | 22% | 24% | 27% | 28% | |

| ≥200% FPL | 50% | 18% | 44% | 69% | 46% | 44% | 29% | 60% | 61% | 48% | 47% | |

FPL = Federal Poverty Level

Using multivariate logistic regression, we evaluated the effects of social and economic characteristics on the odds of health insurance coverage and access to care for immigrant children. Table 2 shows the odds of being uninsured for children of immigrant families by global region of birth. In the unadjusted model, children born in Mexico, South America, the Indian subcontinent, and Asia have significantly higher odds of being uninsured than U.S.-born children of immigrant families. After adjusting for demographic characteristics of the child and social characteristics of the family, the significant results remain. Compared with U.S.-born children of immigrant families, children born in Mexico/Central America have 3.5 times higher odds (95% CI 5 3.1–3.9), children born in South America and Asia have 2.6 times higher odds (95% CI 5 2.0–3.3 and 1.7–3.8, respectively), and children born in India have twice the odds (95% CI 1.3–3.2) of being uninsured.

Table 2.

ODDS oF UnInSURAnCE AMONG CHIlDREN OF IMMIGRANT FAMILIES IN THE U.S.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Region of Child's Birth | ||||

| United States | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Mexico, Central America | 7.46*** | 6.86,8.12 | 3.47*** | 3.10, 3.89 |

| South America | 3.79*** | 3.04,4.73 | 2.56*** | 2.01,3.25 |

| Europe | 1.12 | 0.74, 1.70 | 1.46 | 0.93, 2.28 |

| Russia | 0.99 | 0.51, 1.90 | 1.02 | 0.50, 2.08 |

| Africa | 1.20 | 0.76, 1.89 | 1.25 | 0.78, 2.00 |

| Middle East | 0.93 | 0.46, 1.87 | 0.91 | 0.43, 1.92 |

| Indian subcontinent | 1.60* | 1.06, 2.41 | 2.03** | 1.28,3.21 |

| Asia | 2.06*** | 1.44,2.94 | 2.57*** | 1.73, 3.83 |

| SE Asia | 1.00 | 0.68, 1.47 | 1.01 | 0.67, 1.52 |

| Child Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.98 | 0.93, 1.02 | ||

| Age group | ||||

| 0–4 years | 1.00 | |||

| 5–12 years | 1.20*** | 1.12, 1.29 | ||

| 13–17 years | 1.32*** | 1.21, 1.44 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | |||

| Black | 1.10 | 0.91, 1.32 | ||

| Asian | 1.06 | 0.87, 1.30 | ||

| Other | 0.98 | 0.87, 1.11 | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 1.00 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.59*** | 1.37, 1.85 | ||

| Time in the U.S. | ||||

| 5 years or more | 1.00 | |||

| In U.S. <5 years | 1.75*** | 1.52,2.01 | ||

| Family Social Characteristics | ||||

| Family type | ||||

| Both parents foreign | 1.31* | 1.17, 1.47 | ||

| 1 parent U.S. born | 1.00 | |||

| Single parent foreign | 0.97 | 0.83, 1.15 | ||

| Highest parent education | ||||

| < High school | 2.40*** | 2.08, 2.77 | ||

| High school | 1.82*** | 1.57,2.11 | ||

| Some college | 1.59*** | 1.36, 1.87 | ||

| College degree | 1.00 | |||

| Parents employment | ||||

| No employed parents | 1.00 | |||

| 1 employed parent | 1.29** | 1.10, 1.50 | ||

| 2 employed parents | 1.23* | 1.03, 1.46 | ||

| Poverty Status | ||||

| <100% FPL | 1.85*** | 1.61,2.13 | ||

| 100–199% FPL | 1.99*** | 1.76, 2.24 | ||

| ≥200% FPL | 1.00 | |||

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001

OR=odds ratio

CI=confidence interval

FPL=Federal poverty Level

In addition to region of birth, other significant predictors of uninsurance include age of the child, Hispanic ethnicity, time in the U.S., and family social characteristics. Not surprisingly, children living in the U.S. less than five years have 1.8 times higher odds of uninsurance than those living in the U.S. longer than five years. Parental education also had a strong relationship with child uninsurance. Immigrant children whose highest parent education was less than high school have 2.4 times higher odds of uninsurance than immigrant children who had at least one college-educated parent. Children whose families lived below poverty had significantly higher odds of uninsurance than those whose families lived at or above 200% of the poverty level. Interestingly, children with one or both parents employed had higher odds of uninsurance than children who had no employed parents.

Table 3 shows the odds of delayed care and the odds of foregone care due to cost for children of immigrant families by global region of birth. In the unadjusted model for delayed care, children born in Mexico/Central America, South America, or Russia had significantly higher odds of reporting that they delayed care due to cost in the past 12 months than immigrant children born in the U.S. After adjusting for demographic characteristics of the child and social characteristics of the family, the results for Russia were attenuated. However, significantly higher odds of delayed care for children born in Mexico/Central America (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.6–2.4) and South America (OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.6–3.4) compared with U.S.-born children in immigrant families remained (full results not shown). However, after adjusting for uninsurance, children born in Mexico/Central America were no longer significantly different. In the fully adjusted model, other significant predictors of delayed health care include family poverty. The strongest predictor of delayed care was uninsurance with uninsured immigrant children having 6.5 times higher odds of delayed care than insured immigrant children (95% CI = 5.5–7.7).

Table 3.

ODDS OF DELAYED OR FOREGONE CARE DUE TO COST AMONG CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANT FAMILIES IN THE U.S.

| Delayed Care |

Foregone Care |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Region of Child's Birth | ||||||||

| United States | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Mexico, Central America | 2.54*** | 2.15, 3.01 | 1.18 | 0.96, 1.46 | 2.80*** | 2.34, 3.36 | 1.12 | 0.89, 1.42 |

| South America | 2.48*** | 1.73, 3.55 | 1.67** | 1.14,2.45 | 2.82*** | 1.96, 4.06 | 1.69* | 1.12,2.55 |

| Europe | 1.15 | 0.52, 2.54 | 1.06 | 0.48, 2.35 | 1.15 | 0.38, 3.47 | 1.16 | 0.37, 3.62 |

| Russia | 2.17* | 1.08, 4.34 | 1.91 | 0.78, 4.72 | 1.96 | 0.87, 4.45 | 1.71 | 0.66, 4.45 |

| Africa | 1.77 | 0.82, 3.86 | 1.30 | 0.57, 2.97 | 2.21 | 0.93, 5.25 | 1.67 | 0.71, 3.91 |

| Middle East | 1.07 | 0.39, 2.93 | 1.03 | 0.37, 2.87 | 1.73 | 0.68, 4.39 | 1.65 | 0.59, 4.57 |

| Indian subcontinent | 0.72 | 0.33, 1.56 | 1.14 | 0.51, 2.55 | 0.77 | 0.32, 1.89 | 1.20 | 0.49, 2.97 |

| Asia | 1.31 | 0.60, 2.88 | 1.72 | 0.74, 3.96 | 1.69 | 0.69, 4.10 | 2.15 | 0.86, 5.34 |

| SE Asia | 0.39 | 0.15, 1.00 | 0.59 | 0.23, 1.49 | 0.83 | 0.35, 1.96 | 1.23 | 0.52, 2.93 |

| Insurance status | ||||||||

| Insured | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Uninsured | 6.50*** | 5.49,7.70 | 6.50*** | 5.38, 7.86 | ||||

| Child Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Female | 1.05 | 0.95, 1.17 | 0.99 | 0.87, 1.12 | ||||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 0–4 years | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5–12 years | 1.07 | 0.94, 1.32 | 1.17 | 0.99,1.38 | ||||

| 13–17 years | 1.11 | 0.94, 1.32 | 1.43*** | 1.17, 1.75 | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Black | 1.14 | 0.82, 1.60 | 1.08 | 0.76, 1.53 | ||||

| Asian | 0.51*** | 0.34, 0.75 | 0.56** | 0.38, 0.84 | ||||

| Other | 1.14 | 0.91, 1.42 | 1.06 | 0.79, 1.41 | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0.74* | 0.57, 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.63, 1.15 | ||||

| Time in the U.S. | ||||||||

| 5 years or more | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| In U.S. <5 years | 0.91 | 0.70, 1.18 | 0.86 | 0.65, 1.13 | ||||

| Family Social Characteristics | ||||||||

| Family type | ||||||||

| Both parents foreign | 0.74** | 0.60, 0.93 | 0.75* | 0.59, 0.96 | ||||

| 1 parent U.S. born | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Single parent foreign | 0.99 | 0.75, 1.29 | 1.06 | 0.78, 1.45 | ||||

| Highest parent education | ||||||||

| < High school | 1.02 | 0.79, 1.32 | 1.01 | 0.72, 1.41 | ||||

| High school | 1.09 | 0.83, 1.43 | 1.32 | 0.92, 1.88 | ||||

| Some college | 1.66*** | 1.31,2.10 | 1.53* | 1.09,2.15 | ||||

| College degree | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Parents employment | ||||||||

| No employed parents | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 1 Employed parent | 0.86 | 0.68, 1.09 | 0.93 | 0.72, 1.21 | ||||

| 2 Employed parents | 0.70* | 0.54, 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.65, 1.18 | ||||

| Poverty status | ||||||||

| <100% FPL | 1.00 | 2.26*** | 1.72, 2.98 | |||||

| 100–199% FPL | 1.52*** | 1.22, 1.91 | 1.78*** | 1.38,2.29 | ||||

| ≥200% FPL | 1.56*** | 1.29, 1.89 | 1.00 | |||||

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001

OR = odds ratio

CI= confidence interval

FPL = Federal Poverty Level

The models for foregone care show a pattern strikingly similar to the one for delayed care. In the unadjusted model, compared with U.S.-born children of immigrant families, children born in Mexico/Central America or South America had nearly three times the odds of foregone care in the past year (95% CI = 2.3–3.4 and 2.0–4.1, respectively). Even after adjustment for demographic characteristics of the child and social characteristics of the family, significantly higher odds of foregone care remained for children born in Mexico/Central America (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.5–2.3) and South America (OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.6–3.6) compared with U.S.-born children in immigrant families (full results not shown). After further adjusting for health insurance status, children born in Mexico/Central America were no longer at increased odds for foregone care. Again, the strongest predictor of foregone care in the past 12 months was uninsurance status.

Limitations

The study findings should be considered in light of potential limitations. First, the NHIS is conducted primarily in English or Spanish, making it quite possible that immigrant families who do not speak English or Spanish were underrepresented in the NHIS sample we analyzed. Limited English Proficiency (LEP) has been linked to difficulties obtaining health insurance coverage and access to health care in previous studies.22–23 It is possible that we underestimated the levels of uninsurance, delayed care, and foregone care by systematically excluding those who were not able to complete the survey in English or Spanish.

Second, the region of birth categories used in our analyses are broadly defined. The NHIS does not release detailed country of origin, so we were limited to the regions defined in the NHIS data. The regional groupings are based on geographic proximity to one another and do not take into account economic, political, or social context of the grouped countries. The use of these aggregated region categories may be masking important differences in uninsurance and access to care by specific country of origin within each global region.

Third, we don't have information about which state each person is from. Eight states, including California, chose to use state funds to cover all legal immigrants within their first five years after PRWORA was enacted. A total of 20 states chose to cover some legal immigrants in the first five years—many of these states chose to cover children. State information could be an important predictor of insurance coverage.

Discussion

The U.S. has always been a country of immigrants. Yet at no point in history has the number and need of immigrant children been greater. Immigrant children add up to more than one out of every five children under age 17 and are more likely to be poor, uneducated, and have poor health status. A recent data release by the Census Bureau showed that there were 1.2 million more children living in poverty in 2008 than in 2007. The poverty rate for those who were not U.S. citizens rose significantly to 23.3%.24 Globalization requires that we consider the regions and countries of origin to develop and target social policies to assure the successful assimilation of immigrants and their children.

Our study has demonstrated variability in the social determinants that new immigrants bring to the U.S. by region of birth, which in turn affects their opportunity for success in this country. For all three outcomes, immigrants from Mexico and Central America fare the worst. They come to the U.S. with little or no education and very low incomes. Almost two-thirds of children born in the Mexico/Central America region live in families where no parent has a high school education and almost half live in poverty. Children in families from Mexico/Central America are at an extreme disadvantage for health because of these social characteristics and they represent the single largest group, constituting a third of all immigrant children.

Yet, even controlling for employment, income, and education, immigrants from certain parts of the world are persistently more likely to be uninsured. These include immigrants from Mexico and South America as well as India and Asia. More than income and education must be addressed.

We also found that these and other characteristics also affect access to health insurance coverage and access to care. The amount of time in the U.S. is a significant predictor of coverage, as is parental education, Hispanic ethnicity, and poverty. Interestingly, children with one or both parents employed were more likely to be uninsured than children who had no employed parents. This may be a result of not qualifying for public coverage, as the family may make too much to qualify for public programs such as Medicaid or CHIP, but also not having enough to purchase coverage either from their employer or through the private market.

Social characteristics such as lack of education, poor health status, and living in poverty intersect with the institutional barriers created by U.S. health and welfare policies to limit access to needed health care services. Not surprisingly, the strongest predictor of delayed or foregone care was lack of health insurance coverage with uninsured immigrant children having 6.5 times higher odds of delayed care than insured immigrant children. Again, Mexican/Central American and South American families fare the worst for both delayed and foregone care. Yet, once we control for health insurance coverage, we find little difference between regions in delayed or foregone care, although we still find persistent social determinants (family education and poverty) of delayed or foregone care. Having health insurance coverage as an immigrant is critical to accessing needed health care services.

Demonstrating that health insurance coverage is clearly a significant factor in improving health of immigrant populations is not new. But even when controlling for access to health insurance, lower-income populations face persistent barriers with access to health care, as do older children (age 13–17) and children living in poverty (below 200% of the federal poverty level). It is not health insurance alone but also income and age are critical factors in developing policies to help immigrant children gain access to care. Current policies that restrict such access should be carefully evaluated.

We have documented significant health inequities within the U.S. for immigrant children. Additionally, we know that, “the foundation of adult health is laid in early childhood and before birth. Slow growth and poor emotional support raise the lifetime risk of poor physical health and reduce physical, cognitive and emotional functioning in adulthood.”25[p.14] Past policies limiting access to public programs, social support, and health insurance coverage to children will have far-reaching effects on the health of our future adult population.

While the new Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) alleviated some of the barriers of access to public programs for immigrants by eliminating the five-year residency requirement and relaxing some of the documentation requirements, we must go further. “Universal access to medical care is clearly one of the social determinants of health.”25[p.7] Our study finds that having health insurance coverage reduces the inequities in delayed and foregone care for immigrant children in the U.S. Moving toward a policy where every child is covered without regard to immigration status is needed to ensure health equity for children and for the future adult population.

Appendix NHIS classification of global region of birth

Mexico, Central America, Caribbean Islands

Mexico, all countries in Central America and the Caribbean Island area including Puerto Rico

South America

All countries on the South American continent

Europe

Albania, Austria, Azores Islands, Belgium, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Corsica, Crete, Croatia, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Herzegovina, Holland, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Majorca, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Prussia, Romania, Scotland, Serbia, Sicily, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Yugoslavia

Russia (and former USSR areas)

Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine, and all places formerly a part of the USSR

Africa

All countries on the African continent, plus the Canary Islands, Comoros, Madagascar, Madeira Islands

Middle East

Aden, Arab Palestine, Arabia, Armenia, Bahrain, Cyprus, Gaza Strip, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Syria, Lebanon, “Middle East,” Oman, Palestine, Persia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, West Bank, Yemen

Indian Subcontinent

Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, British Indian Ocean Territory, Ceylon, East Pakistan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tibet, West Pakistan

Asia

Asia, Asia Minor, China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea

SE Asia

Borneo, Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Christmas Island, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam

Elsewhere

Guam, Bermuda, Canada, Greenland, Oceania, as well as “At sea,” “High seas,” “International waters,” “North America”

Unknown

Places that could not be classified in the above categories.

Notes

- 1.World Health Organization/Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization/Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/ publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pourat N, Lessard G, Lulejian A, et al. Demographics, health, and access to care of immigrant children in California: identifying barriers to staying healthy. University of California, Los Angeles; Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: Mar, 2003. Available at: http://www.healthpolicy.ucla.edu/pubs/files/NILC_FS_032003.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nandi A, Galea S, Lopez G, et al. Access to and use of health services among undocumented Mexican immigrants in a U.S. urban area. Am J Public Health. 2008 Nov;98(11):2011–20. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang ZJ, Yu SM, Ledsky R. Health status and health service access and use among children in U.S. immigrant families. Am J Public Health. 2006 Apr;96(4):634–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congress of the United States/Congressional Budget Office . Immigration policy in the U.S. Congressional Budget Office; Washington, DC: Feb, 2006. Available at: http:// www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/70xx/doc7051/02-28-Immigration.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capps R, Fix ME, Ost J, et al. The health and well-being of young children of immigrants. Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2004. Available at: http://www.urban.org/ UploadedPDF/311139_ChildrenImmigrants.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camarota SA. Immigrants in the United States, 2007: a profile of America's foreign-born population. Center for Immigration Studies/Backgrounder; Washington, DC: Nov, 2007. Available at: http://www.cis.org/articles/2007/back1007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Wie A, Ziegenfuss J, Blewett LA, et al. Persistent disparities in health insurance coverage: Hispanic children, 1996 to 2005. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008 Nov;19(4):1181–91. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Health Access Data Assistance Center . REI: data availability for race, ethnicity, and immigrant groups in federal surveys (Issue Brief #17) University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 2009. Available at: http://www.shadac.org/files/shadac/publications/ IssueBrief17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgos AE, Schetzina KE, Dixon LB, et al. Importance of generational status in examining access to and utilization of health care services by Mexican American children. Pediatrics. 2005 Mar;115(3):e322–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Singh GK. Health status and health services utilization among U.S. Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, and other Asian/Pacific Islander children. Pediatrics. 2004 Jan;113(Pt 1):101–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku L, Matani S. Left out: immigrants' access to health care and insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001 Jan–Feb;20(1):247–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K, Dikpo S, Vaden-Kiernan N. NSAF Questionnaire: assessing the new federalism, an urban institute program to assess changing social policies (Report No. 12) Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 1997. Available at: http://www.urban.org/Uploaded PDF/Methodology_12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku L. Health insurance coverage and medical expenditures of immigrants and native-born citizens in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009 Jul;99(7):1322–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . About the global burden of disease project. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/ healthinfo/global_burden_disease/about/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation/University of Washington . Global Burden of Disease Study 2005. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2007. Available at: http://www.globalburden.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations . 63rd session of the General Assembly: panel discussion on globalization and health. United Nations; New York, NY: 2008. Available at: http://www .un.org/ga/second/63/globalization.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center . Integrated health interview series. Version 2.0. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, MN: 2008. Available at: http://www.ihis.us. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson PJ, Blewett LA, Ruggles S, et al. Four decades of population health data: the integrated health interview series. Epidemiology. 2008 Nov;19(6):872–5. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stata Corp . Stata statistical software: release 10.0. Stata Corp; College Station, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stata Corp . Survey data reference manual. Stata Press; College Station, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. The language spoken at home and disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in U.S. children. Pediatrics. 2008 Jun;121(6):e1703–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH, et al. Parental English proficiency and children's health services access. Am J Public Health. 2006 Aug;96(8):1449–55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC, U.S. Census Bureau . Current population reports, P60-236, income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2008. Available at: http:// www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p60-235.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson R, Marmot M, editors. Social determinants of health: the solid facts. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2003. [Google Scholar]