Abstract

Objective:

This project was designed to longitudinally study persons who had antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV) to characterise the serologic course of infection.

Methods:

The subjects were 149 multitransfused patients (141 with thalassaemia major, 3 with thalassaemia intermedia, and 5 with sickle cell anaemia) who had been regularly followed up for 3 to 7 years. Sequential serum samples obtained semi-annually between January 1994 and January 2001 were tested, prospectively, by second or third generation HCV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), followed by confirmatory recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA-2 or RIBA-3).

Results:

Of the 149 patients, 90 did not seroconvert to HCV, whereas 59 had detectable antibodies. On the basis of RIBA results in these 59 patients, 24 (41%) had persistent high antibody levels to structural and non structural HCV antigens, 11 (19%) had persistent low antibody levels, 17 (29%) showed fluctuating antibody levels, and in 5 patients (8%) there was a total or a partial disappearance of specific antibodies (seroreversion), mainly anti-core antibodies. Two patients (3%) had antibody responses that did not fit into any of these four categories. In patients with fluctuating antibody levels, there were periods ranging from 6 months to 2 years when anti-HCV antibodies could not be detected.

Conclusion:

This study shows that the antibody response to HCV in patients who receive frequent blood transfusions is very variable. Individuals who exhibit intermittent seropositivity are a challenge to diagnosis.

Keywords: thalassaemia, antibody response, hepatitis C virus

Hepatitis c virus (hcv), the major cause of parenterally-transmitted and community-acquired non-A, non-B hepatitis, was cloned in 1989.1 The medical importance of HCV resides in its propensity to persist. In the general population, persistent infection leads to chronic hepatitis in 50–80% of patients, often accompanied by an increase in serum transaminase levels.2–4 Chronic HCV infection affects an estimated 170 million individuals worldwide with the majority of countries reporting a prevalence of 1.0–5.5%.5,6 However, in patients with haemoglobinopathies such as thalassaemia major, the prevalence of hepatitis C is high. Before the introduction of routine screening of donated blood for HCV antibody, these patients were at high risk of exposure to the virus as a result of frequent transfusions with packed red blood cells. The reported prevalence in thalassaemics varied geographically from 23% to 72%.7

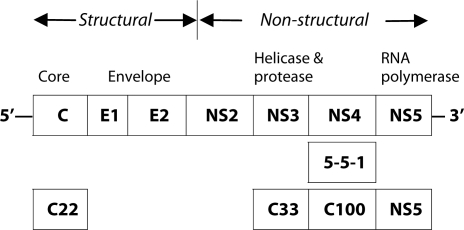

Following the discovery of HCV genome, a variety of diagnostic tests based on detection of anti-HCV antibodies have been developed and refined. Three generations of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have been developed using recombinant and peptide antigens derived from different regions of HCV genome (Figure 1). Each new generation provided incremental improvements in sensitivity to anti-HCV. In high prevalence populations, such as patients with chronic liver disease, third generation ELISAs have high sensitivity and specificity. Unfortunately, they have suboptimal sensitivity and specificity in low prevalence populations, such as blood donors.8 Thus, to confirm the presence of HCV antibodies, immunoblot assays were developed in parallel with ELISAs. The current (third) generation of recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA) detects antibodies to four HCV antigens (Figure 1). Although ELISA and RIBA are useful in the diagnosis of HCV infection, the presence of antibodies which they detect does not necessarily mean that the virus is present. Detection of HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can differentiate between ongoing and resolved infection. Further, PCR is useful in assessing the antiviral response to therapy, and can help resolve weakly positive or negative antibody test results when clinical signs and/or risk factors are compatible with HCV infection. The table compares two generations of ELISA and RIBA with HCV PCR in subjects at low- and high-risk for HCV infection

Figure 1.

Organization of hepatitis C virus genome and location of antigens licensed for diagnostic use.

Since HCV has been identified only recently, little is known either about the natural history of infection, or about the mechanisms associated with the immunologic responses to it. The number of long-term sequential evaluations of viraemia and of anti-HCV immune response has been limited. Thus we undertook a prospective, seven-year study of serological markers of HCV infection in multitransfused patients treated at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) to establish antibody patterns in these subjects.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

From January 1994 to January 2001, a total of 236 patients (127M, 109F) with haemoglobinopathies were treated in the Department of Haematology of Sultan Qaboos University Hospital. Their ages at entry into the study ranged from 6 months to 40 years (median 6.5). Among these patients, 219 had thalassaemia major, 9 had thalassaemia intermedia, and 8 had sickle cell disease. The diagnosis of haemoglobinopathy had been made on the basis of family histories, cell counts, and haemoglobin electrophoresis. All the patients were routinely transfused with packed red blood cells (generally every 4 weeks in patients with thalassaemia major) and were followed up at the day care centre of SQUH.

At approximately 6-month intervals, blood samples were collected at the time of routine visit before transfusion. Serum samples were separated from whole blood within 3 hours after venipuncture, and were kept at +4º C if testing was carried out within 24 hours of collection, or at −20º C if they were to be tested at a later date.

DETECTION OF SERUM HCV ANTIBODIES

Serum samples were screened by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). To assess the specificity of the ELISA, a confirmation recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA) was performed on positive sera. Between 1994 and 1996, second generation ELISAs (Abbott HCV EIA, Abbott IMx HCV, or Abbott Axsym HCV, Abbott Diagnostics Division, Germany) and RIBA (Chiron Corp. Emeryville, California) were used. These assays contain antigens coded by the structural gene (core) and non-structural genes (NS3 and NS4) of HCV (Figure 1). Third generation ELISA (Abbott Axysm HCV 3.0, Abbott Diagnostics Division, Germany) and RIBA (Chiron Corp., Emeryville or Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore) contain an extra antigen from the NS5 region of HCV genome (Figure 1); they were used from 1997 to 2001.

As instructed by the manufacturer, the intensity of each band in the RIBA was rated from 0 to 4+. Results were interpreted as positive, indeterminate or negative based on the intensity and distribution of the bands. The RIBA score of each band was a measure of the level of antigen-specific antibody in the sample.

DETECTION OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV)

Testing for HIV antibodies was performed by ELISA (Abbott Diagnostics, Germany) with confirmatory Western blot assays (Novopath HIV-1 from Biorad, or New LavBlot I from Diagnostics Pasteur, for HIV-1 and New LavBlot II, from Diagnostics Pasteur for HIV-2).

RESULTS

When tested by second or third generation ELISA, 139 (59%) patients had no detectable anti-HCV antibodies at any time during the study period, whereas 97 (41%) patients were seropositive. Of this total of 236 patients, 149 had been followed up for 3 to 7 years (mean 6.5), and had serum samples collected and tested every six months. Data of these patients were analysed further to establish antibody responses to HCV. Of the 149 patients, 90 (89 with thalassaemia major, 1 with thalassaemia intermedia) did not seroconvert to anti-HCV during the study period. Fifty nine patients (52 thalassaemia major, 2 thalassaemia intermedia, 5 sickle cell disease) had detectable anti-HCV antibodies when tested by second or third generation ELISA and RIBA. On the basis of RIBA results, four serological patterns were observed.

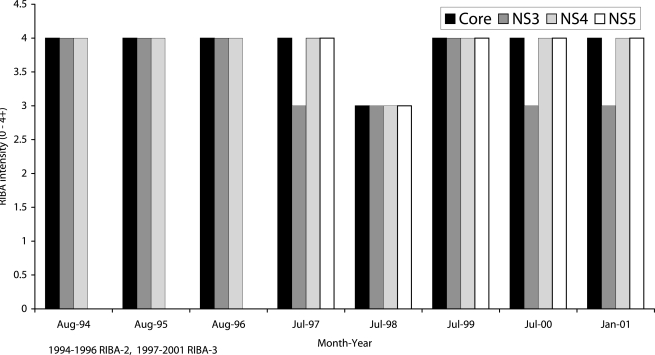

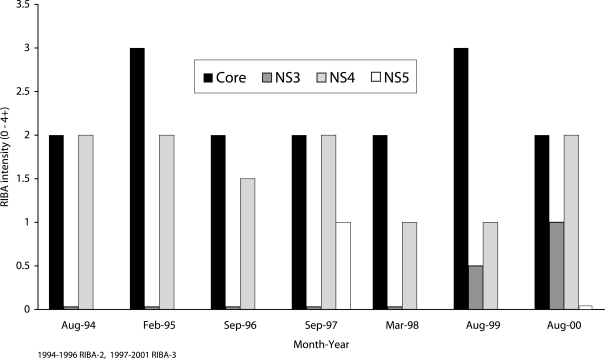

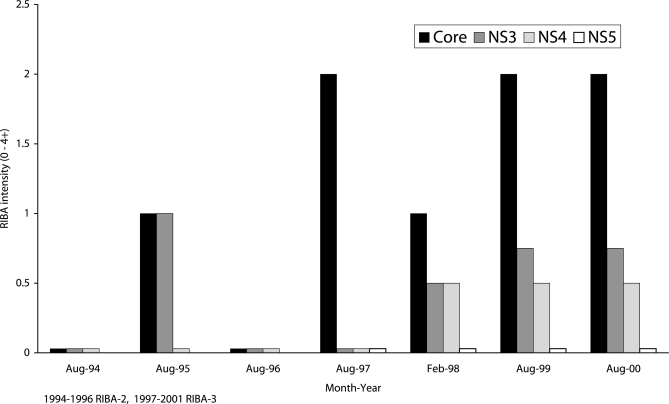

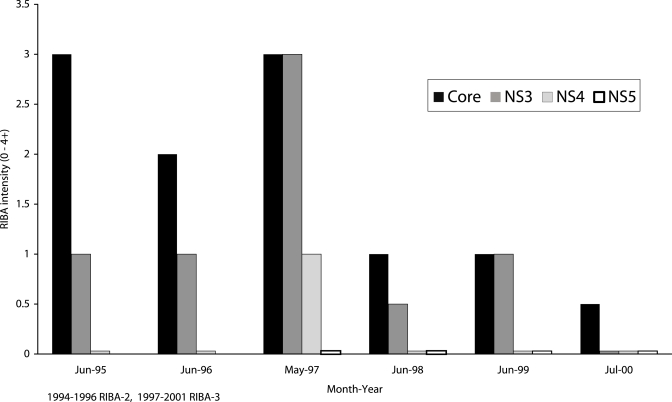

Twenty four out of 59 patients (41%) had persistently elevated antibody levels, with RIBA scores of 3+ or 4+ to structural and non structural HCV antigens. Figure 2 shows data of one such patient. Eleven patients (19%) had low antibody levels, with RIBA scores of 2+ for nearly all HCV antigens throughout the study period. Samples from these patients were weakly positive or indeterminate (Figure 3). In 17 patients (29%), there were wide fluctuations in antibody levels (Figure 4). They showed transitions between RIBA-indeterminate and –positive status interspersed with RIBA-negative status. Some of the patients had no detectable antibodies for periods of 6 months to 2 years.

Figure 2.

Six and half years’ follow-up in a thalassaemic patient, showing persistently high levels of antibodies to hepatitis C virus antigens

Figure 3.

Persistent low levels of antibodies to hepatitis C virus antigens in a patient who was followed over a six-year period

Figure 4.

Fluctuating levels of antibodies to hepatitis C virus antigens in a atient over a six-year period of follow-up

There was progressive loss of HCV antibodies (seroreversion) in 5 patients (8%), one of whom lost all HCV antibodies (Figure 5). None of these patients was on antiviral therapy for HCV, and none was HIV-infected.

Figure 5.

Seroreversion in a patient infected by hepatitis C virus

Serological response in 2 patients did not fit into any of these 4 categories. One patient had low antibody levels for 5 consecutive years followed by a strong antibody response. The second patient, who had been RIBA-negative for 2 consecutive years, seroconverted in 1999, lost all antibodies in 2000, and seroconverted again in 2001.

DISCUSSION

Approximately two thirds of our multitransfused patients who were regularly tested for a mean period of 6.5 years did not seroconvert to anti-HCV, strongly suggesting that they did not acquire HCV infection during the study period. In the one third that were seropositive, our data indicate that the antibody response to HCV infection is variable. Four serological patterns were observed. Most patients (41%) had high antibody levels that were sustained throughout the study period, and 19% had persistent, but low antibody levels. In a similar study in homosexual men, persistent anti-HCV seropositivity was reported in 16 of 26 subjects.14

Intermittent seropositivity which we observed relatively frequently could be attributed to reinfection. The possibility of reinfection with HCV arises because of at least two reasons. First, chimpanzee studies have shown that recovery from HCV infection does not confer immunity to the individual.15 Second, although screening of blood donations for HCV antibodies has drastically reduced the risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C, a residual risk, mainly linked to viraemic bloods donated by seronegative individuals, persists.5,16 Fluctuating HCV serology may be common in the general population.14 It poses a challenge to diagnosis and contributes to the continuing problem of transfusion-associated hepatitis.

Partial or full seroreversion may be observed in three circumstances: spontaneously, induced by therapy, and in conjunction with HIV infection. In our patients, sero-reversion was spontaneous and was probably associated with clearence of infection.17, 18 Our findings indicate that spontaneous seroreversion is relatively rare and are in agreement with observations by others. In a longitudinal study lasting 8 years, only 2 of 30 patients with thalassaemia major seroreverted.17. An assessment of 103 transfusion-associated HCV cases 20 years after disease onset revealed that 10% had lost HCV serologic markers18.

The presence of detectable anti-HCV antibody may reflect a past resolved infection or chronic persistent infection. Usually, the majority (≥80%) of RIBA positives are viraemic.9–13 Samples from persons with persistent and intermittent HCV ELISA seropositivity are positive by polymerase chain reaction 76% and 50% of the time respectively.14 Based on these data, we infer that the antibody responses we observed reflect different dynamics of HCV infection. We have recently started prospective evaluations of viraemia by PCR in parallel with antibody studies to have a better understanding of the natural history of HCV infection and the antibody response to it.

CONCLUSION

This study clearly shows that the antibody response to HCV infection in patients who receive frequent blood transfusions, such as those with thalassaemia major, is very variable. HCV infection in these patients is not always characterised by a persistent antibody response. A significant proportion may either show intermittent seropositivity, or they may progressively lose anti-HCV antibodies. This variability in antibody levels poses difficulties in the serological diagnosis of viral hepatitis C.

Table 1.

RIBA and PCR testing in anti-HCV (ELISA) positive blood donors and patients with suspected viral hepatitis C population

| Study population | Generation ELISA/RIBA | Number ELISA positive | RIBA

|

%PCR positive in RIBA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Posα | %Indβ | %Negδ | Pos | Ind | Neg | |||

| Blood donors9 | 2/2 | 340 | 23 | 38 | 39 | 84 | 6 | 0 |

| Blood donors10 | 2/2 | 1105 | 17 | 38 | 45 | 75 | 2 | NDϕ |

| Blood donors11 | 2/3 | 750 | 37 | 29 | 35 | 80 | 1 | 0 |

| Patients10 | 2/2 | 283 | 79 | 11 | 10 | 90 | 68 | ND |

| Patients12 | 3/3 | 114 | 46 | 34 | 20 | 100 | 46 | 0 |

| Patients13 | 3/3 | 54 | 94 | 6 | 0 | 94 | 0 | 0 |

Positive,

Indeterminate,

Negative,

No data

REFERENCES

- 1.Choo Q-L, Kuo G, Weiner A, Overby L, Bradley D, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poel CL, Cuypers HT, Reesink HW. Hepatitis C virus six years on. Lancet. 1994;344:1475–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong MJ, El-Farra NS, Reikes AR, Co RL. Clinical outcomes after transfusion-associated hepatitis. N Eng J Med. 1995;332:1463–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter HJ, Seef LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Sem Liver Disease. 2000;20:17–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrine SK, Weinberg DS. Epidemiology of hepatitis C viral infection. Infect Med. 1999;16:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Hepatitis C global prevalence (update) Weekly Epidemiol Rec. 1999;75:425–427. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Montalembert M, Girot R, Mattlinger B, Lefrere JJ. Transfusion- dependent thalassaemia: viral complications (epidemiology and follow-up) Sem Haematology. 1995;32:280–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiff ER, de Medina M, Kahn R. New perspectives in the diagnosis of hepatitis C. Sem Liver Disease. 1999;19:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dow BC, Coote I, Munro H, McOmish F, Yap PL, Simmonds P, et al. Confirmation of hepatitis C virus antibody in blood donors. J Med Virol. 1993;41:215–220. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bresters D, Zaaijer HL, Cuypers HTM, Reesink HW, Winkel IN, van Exel-Oehlers PJ, et al. Recombinant imunoblot assay reaction patterns and hepatitis C virus RNA in blood donors and non-A, non-B hepatitis patients. Transfusion. 1993;33:634–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33893342743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damen M, Zaaijer HL, Cuypers HTM, Vrielink H, van der Poel CL, Reesink HW, et al. Reliability of the third-generation recombinant immunoblot assay for hepatitis C. Transfusion. 1995;35:745–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35996029158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soffredini R, Rumi M, Lampertico P, Aroldi A, Ttarantino A, Ponticelli C, et al. Increased detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus in renal transplant patients by third generation assays. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:437–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courouce AM, Bouchardeau F, Chauveau P, Le Marrec N, Girault A, Zins B, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in haemodialysed patients: HCV-RNA and anti-HCV antibodies (third generation assays) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndimbie OK, Nedjar S, Kingsley L, Riddle P, Rinaldo C. Long-term serologic follow-up of hepatitis C virus-seropositive homosexual men. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1995;2:219–224. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.2.219-224.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farci P, Alter HJ, Govindarajan S, Wong DC, Engle R, Lesniewski RR, et al. Lack of protective immunity against reinfection with hepatitis C virus. Science. 1992;258:135–140. doi: 10.1126/science.1279801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugitani M, Inchauspe, Shindo M, Prince AM. Sensitivity of serological assays to identify blood donors with hepatitis C viraemia. Lancet. 1992;339:1018–1019. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90538-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefrère JJ, Guiramand S, Lefrère F, Mariotti M, Aumont P, Lerable J, et al. Full or partial seroreversion in patients infected by hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:316–322. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeff LB, Hollinger FB, Alter HJ, Wright EC, Bales ZB, the NHLBI Study Group Long-term morbidity of transfusion-associated hepatitis (TAH) C. Hepatology. 1998;28:407A. [Google Scholar]