Abstract

Arsenate is a pentavalent form of arsenic that shares similar chemical properties to phosphate. It has been shown to be taken up by phosphate transporters in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic microbes such as yeast and Escherichia coli. Recently, the arsenate uptake in vertebrate cells was reported to be facilitated by mammalian type II sodium/phosphate transporter with different affinities. As arsenate is the most common form of arsenic exposure in aquatic system, identifying the uptake pathway of arsenate into aquatic animals is a crucial step in the elucidation of the entire metabolic pathway of arsenic. In this study, the ability of a zebrafish phosphate transporter, NaPi-IIb1 (SLC34a2a), to transport arsenate was examined. Our results demonstrate that a type II phosphate transporter in zebrafish, NaPi-IIb1, can transport arsenate in vitro when expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. NaPi-IIb1 mediates a high-affinity arsenate transport, with a Km of 0.22 mM. The natural substrate of NaPi-IIb1, dibasic phosphate, inhibits arsenate transport. Arsenate transport via NaPi-IIb1 is coupled with Na+ and exhibits sigmoidal kinetics with a Hill coefficient of 3.24 ± 0.19. Consistent with these in vitro studies, significant arsenate accumulation is observed in all examined zebrafish tissues where NaPi-IIb1 is expressed, particularly intestine, kidney, and eye, indicating that zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 is likely the transport protein that is responsible for arsenic accumulation in vivo.

Introduction

Arsenic is a ubiquitous, naturally occurring metalloid found in the earth's crust.1 Arsenic can also enter the biosphere through man-made sources such as arsenic-containing herbicides, pesticides, and wood preservatives.1 The inorganic form of arsenic is classified as a type IA human carcinogen.2 The detrimental effects of arsenic on human health are well documented, and it is associated with multiple types of cancers affecting the skin, lung, urinary bladder, kidney, and liver.3 In addition, arsenic exposure through drinking water is associated with cardiovascular and neurological disorders and recently with diabetes mellitus.1,4

In water, arsenic is found in two oxidation states, either as AsIII (arsenite) or AsV (arsenate), with AsV being more predominant in the oxidizing environment.5,6 AsIII is a neutral molecule and can be actively transported into the cell by aquaglyceroporins in zebrafish and humans.7,8 However, unlike AsIII, AsV is charged in physiological pH. AsV shares high chemical similarity to phosphate, as they are both tetrahedral molecules found in group Va of the periodic table and they share three similar dissociation constants.9,10 The pKa values of arsenic acid (AsO(OH)3) are 2.26, 6.76, and 11.29, and that of phosphoric acid (PO(OH)3) are 2.16, 7.21, and 12.32.9 Because of the structural similarity between AsV and phosphate, AsV is a well-known competitive inhibitor of enzymes that involve phosphate, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, as well as the sodium pump and anion exchanger in human erythrocytes.9,11 AsV additionally uncouples oxidative phosphorylation by substituting phosphate in ATP, leading to the formation of ADP-arsenate.12 Although AsV is generally considered less toxic than other species of arsenic, it undergoes a series of reductions and methylations upon entering the cell, which lead to the generation of other more toxic species such as inorganic AsIII as well as organic monomethyl or dimethyl metabolites and therefore amplified toxicity.1,13 These arsenic species produced through AsV metabolism are implicated in pyruvate dehyrdogenase inhibition, reactive oxygen species formation, gene amplification, and apoptosis.1,3

Although competitive inhibition between phosphate and arsenate has long been observed,14 the molecular details of this inhibition have been recently identified. Because of the analogous structures of AsV and phosphate, AsV is capable of entering Escherichia coli cells through phosphate transporters. Specifically, the Pit and Pst E. coli phosphate transporters can transport AsV.13,15 In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a single mutation in pho84 and a double mutation in pho86 and pho87 confer AsV resistance, which indicates these are likely to permeate AsV.16,17 Inhibition between AsV and phosphate was observed in vertebrates, suggesting that AsV and phosphate share a similar transporter in higher organisms. Specifically, in rats, AsV inhibits the function of intestinally expressed sodium/phosphate cotransporter, NaPi-IIb (SLC34A2).10 Recently, the same group demonstrated that AsV is the transportable substrate of type II sodium phosphate transporter IIb, IIa, and IIc.18 Among them, NaPi-IIb has the highest affinity but the other two exhibited about 10 times lower affinity than natural substrate phosphate.18

To elucidate the uptake process of arsenate by zebrafish, we investigated the transport properties of AsV by a zebrafish homolog of the rat NaPi-IIb sodium-coupled phosphate transporter. Three families of sodium-coupled phosphate transporter proteins have been identified: SLC17 (type I), SLC34 (type II), and SLC20 (type III).10,19,20 The type II solute carrier family (SLC34) of proteins facilitates uptake of divalent phosphate (HPO42−) in apical membranes of numerous organism including human, rat, and zebrafish.10,20,21 Zebrafish express two isoforms of the type II phosphate transporter NaPi-IIb, specifically NaPi-IIb1 (SLC34a2a) and NaPi-IIb2 (SLC34a2b).21,22 In this study, a zebrafish NaPi-IIb1, which is expressed in the intestine, eye, and kidney of zebrafish, is examined.22 Zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 is known to transport HPO42− with high affinity (Km(Pi) = 250 μM), and we here investigate NaPi-IIb1 as a potential uptake route of toxic arsenate.22

Fish are well known for their high tolerance and accumulation of toxic metals and metalloids.23 Although arsenic accumulation has been studied in multiple aquatic species, mechanistic studies into the pathways of arsenic uptake and detoxification are lacking. Fish can take up arsenic via gills or diet, and tissue accumulation patterns vary between species.24 For example, whitefish accumulate little arsenic in muscle.25 The fish species Tribolodon hakonensis collect arsenic mostly in the eye.24 Gender-related accumulation of arsenic was observed in smooth toadfish.26 Once inorganic arsenic is taken up into tissues, it can be modified into other forms. In many species, fish exposed to inorganic arsenic accumulate the organic types, arsenobetaine, arsenochroline, arsenolipids, and arsenosugars. Usually, arsenobetaine is the major end product (up to 95%) and is also called fish arsenic. However, it is not certain whether these organic arsenicals are synthesized within the fish tissues or whether they are present in the diet. Arsenate is the predominant inorganic arsenic species in flowing water.27 As fish is an important commercial food, both the processes of arsenic uptake and accumulation are of great concern. For those reasons, we investigated arsenate accumulation in zebrafish, followed by a speciation analysis for the arsenic accumulated in a variety of tissues.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of zebrafish NaPi-IIb1

Zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 was commercially obtained (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and fully sequenced for verification. It was amplified using a pair of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers with BglII and XhoI restriction sites (forward primer: 5′-GCA GAT CTA TGG CAC CAC GTC CAA AGC AGG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GCC GAT CTA TAA AGA TGT TGC CTT CAG-3′). NaPi-IIb1 was initially cloned into pGEMT-easy (Promega, Madison, WI) and then subcloned into Xenopus laevis expression vector pL2-5.28 The gene of NaPi-IIb1 was fully sequenced and preserved 100% sequence identity to BC096858.1. The resulting plasmid was termed as pNaPi-IIb1.

Expression of NaPi-IIb1in X. laevis oocytes

The pNaPi-IIb1 plasmid was linearized using Not1. Then the capped cRNA of NaPi-IIb1 was transcribed in vitro using mMessage mMachine T7 ultra kit (Ambion Co., Austin, TX). Stage V-VI X. laevis oocytes were isolated and treated with 0.2% collagenase A (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 2 h. The defoliated oocytes were injected with 25 ng (25 nL volume) of zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 cRNA. Oocytes were then incubated in ND96 complete buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes [pH 7.5], supplied with 1 g/L gentamicin) for 3 days at 16°C and used for uptake assays.

Transport assays and metalloid measurement in X. laevis oocytes

For time-dependent uptake, oocytes were incubated in 100 μM potassium arsenate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in ND96 buffer (pH 7.4) for increasing time intervals (0, 15, 30, and 60 min) at room temperature. For kinetic analysis, NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes were incubated in increasing concentrations (0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mM) of potassium arsenate dissolved in ND96 buffer. Oocytes in all non–time-dependent transport assays were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. To determine phosphate inhibition, oocytes were incubated in 200 μM potassium arsenate with increasing concentrations (0, 0.1, 5.0, 1.0, and 3.0 mM) of dibasic sodium phosphate (Sigma). Sodium dependence was measured by incubating oocytes in ND96 buffer containing 100 μM potassium arsenate, and increasing concentrations (10, 50, 100, 140, 160, 240, and 300 mM) of sodium chloride (Sigma), with appropriate concentrations of choline chloride (Sigma) to maintain consistent osmolarity. After incubation, oocytes were washed three times with ND96 buffer, treated with 70% nitric acid at 70°C for 2 h, and diluted to 2 mL final volume with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water in preparation of metalloid quantification. Arsenic uptake was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, ELAN 9000; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Arsenic exposure in zebrafish adults and larvae

Zebrafish larvae were treated with 300 ppb potassium arsenate for 2, 4, and 6 days postfertilization (dpf). After treatment, the larvae were rinsed in arsenic-free water and collected for arsenic quantification; 150 larvae were pooled together and homogenized as one sample. Adult zebrafish were treated with 5 ppm potassium arsenate for continuous 4 days without feeding. After exposure, zebrafish were washed with clean water to remove residual arsenate and then euthanized with 0.3 mM tricaine (MCA222; Sigma). Adult organs including the brain, eye, gill, heart, intestine, kidney, liver, muscle, and skin were isolated. The specific organs from five fish were pooled together as one sample, and totally three samples were obtained for statistical analysis. Samples were weighed and treated in 70% nitric acid. Metalloid quantification was performed as previously described by ICP-MS.8

Expression of NaPi-IIb1 in zebrafish tissues

Using the primer pair, 5′GCTCATTCTGTGCACTTGC3′ and 5′CTATAAAGATGTTGCCTTCAG3′, nested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed to investigate the expression sites of NaPi-IIb1 in zebrafish. Tissues were isolated from adult zebrafish, including brain, eye, gill, heart, intestine, kidney, liver, muscle, and skin, followed by mRNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, which have been previously described.8 Zebrafish beta-actin was used as control.

Arsenic speciation by HPLC-ICP-MS

To study the different arsenic species in zebrafish tissues, adult zebrafish were exposed to 5 ppm of potassium arsenate for 96 h. After treatment, tissues were isolated, pooled (10 fish tissues were used as one sample), and weighed. All tissue samples were homogenized in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) to make a final concentration of 100 mg/mL, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were filtered with a Microcon Ultracel YM-3 centrifugal filter (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA). Arsenic speciation of the filtered samples was performed with a Series 2000 HPLC connected to an ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) using a Jupiter 5 μ C18 300A reverse-phase C18 column (Chromservis s.r.o., Brno, Czech Republic), as previously described.29

Statistical analysis

For the oocyte transport assays, each data point includes 6–9 oocytes. Mean value and standard deviation were calculated using SigmaPlot 10.0. The p-value was calculated using the same software (Student's t-test). p < 0.05 is considered significant. For kinetic analysis of arsenic transport, data were analyzed using hyperbolic, single, rectangular regression analysis in SigmaPlot 10.0. Kinetic analysis of sodium dependence was performed using the four-parameter Hill function, also in SigmaPlot 10.0.

Results

Zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 facilitates high affinity uptake of pentavalent arsenate (AsV) in vitro

Zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 is a type II member of the SLC34 family of phosphate transporter proteins, and the typical substrate of type II proteins of this family is dibasic phosphate (HPO42−). NaPi-IIb1 shares a high sequence identity with homologous proteins in human and rat, having 60% shared identity with human NaPi-IIb and 64% with rat NaPi-IIb.

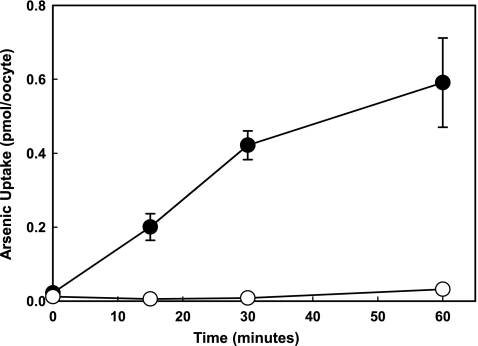

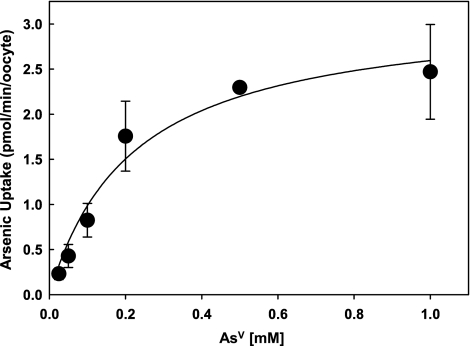

Zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 catalyzes transport of AsV when expressed in X. laevis oocytes in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1). The kinetic properties of arsenate transport indicate that NaPi-IIb1 has a high affinity for arsenate with Km(AsV) = 0.22 mM (Fig. 2). This is comparable to the known affinity of NaPi-IIb1 for divalent phosphate, [Km(HPO42−) = 0.25 mM].22 These similar affinity constants suggest that arsenate and phosphate might share a similar translocation pathway within the NaPi-IIb1 protein. The Vmax for arsenate transport by NaPi-IIb1 was determined as 3.17 pmol/min/oocyte.

FIG. 1.

AsV is facilitated by zebrafish NaPi-IIb1. NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes were incubated in ND96 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 100 μM potassium arsenate for 0, 15, 30, or 60 min. at room temperature. Nine oocytes were used for each data point. Water-injected oocytes were used as controls. Black circles represent NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes, and white circles represent controls.

FIG. 2.

Kinetic parameters of AsV transport by zebrafish NaPi-IIb1. NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes were incubated in ND96 buffer (pH 7.4) containing increasing concentrations of potassium arsenate (0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 mM) for 30 min at room temperature. Nine oocytes were used for each data point. NaPi-IIb1 transports arsenate with fairly high affinity. The Km and Vmax values for arsenate transport by zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 are 0.22 mM and 3.17 pmol/min/oocyte.

Dibasic phosphate inhibition of AsV uptake and sodium-dependent AsV uptake via NaPi-IIb1

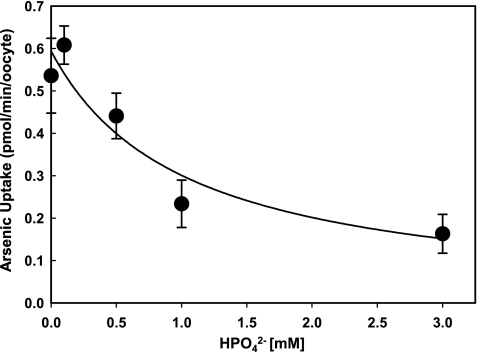

Arsenate has been demonstrated to inhibit uptake of dibasic phosphate (HPO42−) by rat NaPi-IIb, with an inhibitory constant of Ki = 50 μM, and later it was found that this permease transports arsenate.10,18 The inhibitory properties of phosphate on arsenate uptake by zebrafish NaPi-IIb1 was examined (Fig. 3). HPO42− was found to be an efficient inhibitor of AsV uptake. Inhibition of AsV uptake by HPO42− may decrease arsenate accumulation inside cells, leading to lowered arsenic toxicity.

FIG. 3.

Dibasic phosphate (HPO42−) inhibits AsV uptake by NaPi-IIb1. NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes were incubated in 100 μM potassium arsenate with increasing concentrations of dibasic sodium phosphate (0, 0.1, 5.0, 1.0, and 3.0 mM). Nine oocytes were used for each data point. AsV transport decreases with increasing phosphate concentration. The experiment was performed in ND96 buffer (pH 7.4, with neglectable changes with addition of dibasic sodium phosphate up to 3.0 mM).

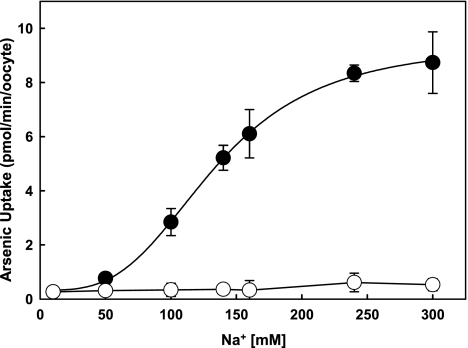

Both phosphate and arsenate transports via NaPi-IIb1 are sodium coupled. A relatively high concentration of Na+ is required to saturate arsenate transport (approximately 190 mM; data derived from SigmaPlot 10.0 by fitting into sigmoidal curve; Fig. 4). Therefore, the efficiency of toxic arsenate uptake is dependent on ionic strength, which is variable in aquatic animals. We found that the relationship between arsenate uptake and sodium concentration is sigmoidal, with a Hill coefficient of 3.24 ± 0.19, which indicates strong positive cooperative interaction, suggesting that several sodium-binding sites might exist in the transport channel. Further structural studies may elucidate this coupling mechanism. It is known that higher osmotic may induce internal gene expression. However, in a water-injected control we did not observe any uptake at the same osmotic condition (Fig. 4), which indicates the Na+-dependent AsV uptake is mediated by NaPi-IIb1, not unspecific transporters. An experiment using choline without Na+ at the same osmolarity will be performed at a later time to verify the specificity of this transport.

FIG. 4.

Arsenate uptake by NaPi-IIb1 is sodium dependent. NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes were incubated in 100 μM potassium arsenate with different concentrations of sodium chloride (10, 50, 100, 140, 160, 240, and 300 mM). Choline chloride was added in appropriate concentrations to maintain osmolarity. Four oocytes were used for each data point. Water injected oocytes were used as controls. Arsenate transport by NaPi-IIb1 is sodium coupled and exhibits sigmoidal kinetics with a Hill coefficient of 3.24 ± 0.19, which indicates strong positive cooperativity. Filled closed circles represent NaPi-IIb1–injected oocytes, and unfilled closed circles represent water-injected controls.

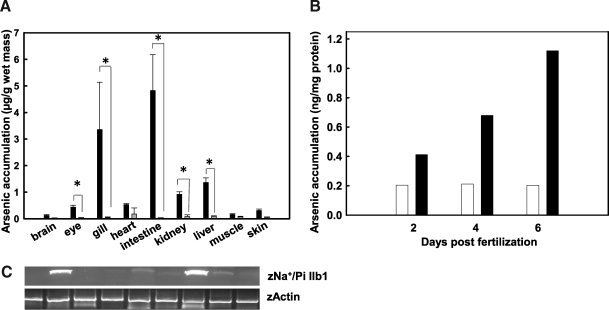

Arsenate accumulates in zebrafish larvae and different adult zebrafish tissues

When exposed to arsenate, multiple zebrafish organs exhibited significantly higher arsenate accumulation when compared with the unexposed control zebrafish (Fig. 5A). Eye, intestine, and kidney have been previously reported to express Na+/Pi-IIb1, and these three tissues experienced particularly high arsenate accumulation (0.87, 9.66, and 1.87 μg/g, respectively). Our studies using RT-PCR showed that in addition to the tissues that has been reported, liver is also an organ that highly expresses NaPi-IIb1 (Fig. 5C), which is consistent without higher arsenic accumulation in liver. Arsenic accumulation also occurred in other tissues that do not express NaPi-IIb1, such as gill, which indicates that other arsenate transporters exist in multiple zebrafish organs. Zebrafish can accumulate arsenate in relative early developmental stage, with larvae being able to accumulate arsenate as early as 4 dpf, when compared with a control. Arsenic accumulation continues to increase along with exposure time (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Arsenic accumulates in adult zebrafish tissues and larvae. (A) In adults, specific tissues from five fish were pooled together as one sample, and totally three samples (15 fish) were used for statistical analysis after 4 days of exposure to 5 ppm sodium arsenate. The eye, intestine, liver, and kidney are adult tissues known to express NaPi-IIb1 and they experienced relatively high arsenate accumulation (0.87, 9.66, and 1.87 μg/g, respectively). The p-value (p < 0.001) was calculated in these tissues and labeled in the figure. Black bars represent arsenate-exposed zebrafish and white bars represent unexposed controls. Asterisk represents significance (p < 0.05). (B) Zebrafish larvae were exposed to 300 ppb sodium arsenate at different days postfertilization. Each experiment contained approximately 150 larvae. The arsenic accumulation was calculated using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Controls were applied to compare the arsenic accumulation in different early developmental stages. White bar: unexposed fish; black bar: exposed fish. (C) Expression of mRNA of NaPi-IIb1 in zebrafish. Tissues were isolated from adult zebrafish and homogenized, and cDNA was prepared. Zebrafish beta-actin was used as a positive control.

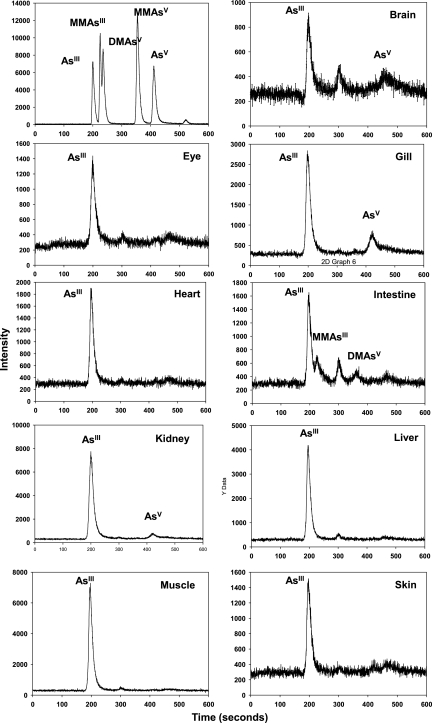

To study the arsenic species after tissue accumulation, tissues were isolated and assayed using HPLC-ICP-MS (Fig. 6). Our results showed that the AsV that was exposed and taken up can be reduced inside cells almost completely to AsIII, which is a more active and carcinogenic form. The unexposed fish only give a minor peak of AsIII, which might be due to the trace amount of arsenic in water and food (figure not shown).

FIG. 6.

Arsenic speciation in zebrafish tissues. Zebrafish were exposed to potassium arsenate at 5 ppm for 4 days and different tissues were isolated for specific assays using high-performance liquid chromatography-ICP-MS. Ten fish tissues were combined as one sample. Different inorganic and organic arsenicals were used as standard.

Discussion

Arsenate toxicity is primarily due to its ability to compete with phosphate in critical enzymatic reactions, and the uptake pathway of arsenate into the cell has been recently demonstrated by type II sodium/phosphate transporters of mouse, rat, and humans.18 In humans, these transporters play a critical role in maintaining phosphate homeostasis in the intestine and kidney of humans, two organs that are principally involved in maintaining 0.1% of total body phosphate in extracellular spaces.19,20 In salivary and mammary glands, liver, and testes, type II transporters participate in regulation of phosphate concentration in luminal fluids.20 Our results show that the zebrafish phosphate transporter, NaPi-IIb1, facilitates arsenate uptake with an affinity comparable to that for its natural substrate, phosphate. Because of the chemical similarity between phosphate and arsenate, NaPi-IIb1 cannot distinguish between the toxic and essential elements. We also show that phosphate inhibits arsenate transport, and this property may enable the in vivo attenuation of arsenate under the condition of high physiological phosphate concentration. If physiological phosphate concentration is not sufficiently high, it is reasonable to predict that arsenate could be transported into the cell via the NaPi-IIb1 phosphate transporter. Thus, the nutrient level of phosphate could greatly impact the overall toxicity of ingested arsenate.

Differential arsenic accumulation is mostly associated with expression of various arsenic uptake systems.13 Our results show that arsenate extensively accumulates in zebrafish tissues (Fig. 5A), with higher concentrations found in intestine, kidney, liver, and eyes, which are sites of NaPi-IIb1 expression (this study). Based on the broad accumulation of AsV, zebrafish probably have other transporter systems that allow toxic AsV to accumulate in other tissues. Those systems likely include other types of phosphate transporters that also facilitate arsenate transport across the cell membrane, and we will investigate the additional routes of arsenate cellular uptake in the future. Transport of arsenate by NaPi-IIb2 in oocytes was negative (data not shown). In brief, it is likely that the extensive expression of different phosphate transporters enables uptake of pentavalent arsenate and subsequently leads to accumulation in a variety of zebrafish tissues.

Once taken up inside cells, the less-toxic AsV is reduced to more toxic AsIII in all tested organs, as shown in Figure 6. This endogenous reduction has been observed in animals.30 Although it was widely reported that mammals have a methylation system that can convert inorganic arsenicals to organic methylated arsenicals, including MMAIII (monomethylarsonous acid), MMAV (monomethylarsonic acid), DMAIII (dimethylarsonous acid), and TMAO (trimethylarsine oxide),31 very low amount of the methylated arsenical species were observed at our short-term exposed zebrafish (Fig. 5C). Instead, the AsIII is the dominant species that can be detected in different tissues.

The observation that arsenate is accumulated by a phosphate transporter is not unexpected, as AsV has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of phosphate transport.10 The uptake properties resemble those of phosphate transport by NaPi-IIb1 and support our hypothesis that AsV is adventitiously taken up by a nutrient transporter through molecular mimicry. Further studies will examine transport mechanisms for both substrates and in vivo roles of this transporter using transgenic zebrafish.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH (ES016856 to Z.L.). The authors appreciate Dr. Barry P. Rosen (Florida International University) for his critical review and editing of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Mandal BK. Suzuki KT. Arsenic round the world: a review. Talanta. 2002;58:201–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Overall Evaluations of Carcinogenicity. An Updating of IARC Monographs. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tapio S. Grosche B. Arsenic in the aetiology of cancer. Mutat Res. 2006;612:215–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng CH. Arsenic exposure and diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:2728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.812. author reply 2728–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SL, et al. Trace element concentration and arsenic speciation in the well water of a Taiwan area with endemic blackfoot disease. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;48:263–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02789408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terlecka E. Arsenic speciation analysis in water samples: a review of the hyphenated techniques. Environ Monit Assess. 2005;107:259–284. doi: 10.1007/s10661-005-3109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z, et al. Arsenite transport by mammalian aquaglyceroporins AQP7 and AQP9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6053–6058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092131899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamdi M, et al. Arsenic transport by zebrafish aquaglyceroporins. BMC Mol Biol. 2009;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamiya K. Cruse WB. Kennard O. The arsonomethyl group as an analogue of phosphate. An X-ray investigation. Biochem J. 1983;213:217–223. doi: 10.1042/bj2130217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villa-Bellosta R. Sorribas V. Role of rat sodium/phosphate cotransporters in the cell membrane transport of arsenate. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballatori N. Transport of toxic metals by molecular mimicry. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):689–694. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore SA. Moennich DM. Gresser MJ. Synthesis and hydrolysis of ADP-arsenate by beef heart submitochondrial particles. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6266–6271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen BP. Biochemistry of arsenic detoxification. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginsburg JM. Renal mechanism for excretion and transformation of arsenic in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1965;208:832–840. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.208.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg H. Gerdes RG. Chegwidden K. Two systems for the uptake of phosphate in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:505–511. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.2.505-511.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bun-ya M, et al. Two new genes, PHO86 and PHO87, involved in inorganic phosphate uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1996;29:344–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giots F. Donaton MC. Thevelein JM. Inorganic phosphate is sensed by specific phosphate carriers and acts in concert with glucose as a nutrient signal for activation of the protein kinase a pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1163–1181. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villa-Bellosta R. Sorribas V. Arsenate transport by sodium/phosphate cotransporter type IIb. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;247:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murer H. Forster I. Biber J. The sodium phosphate cotransporter family SLC34. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:763–767. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Virkki LV, et al. Phosphate transporters: a tale of two solute carrier families. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F643–F654. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00228.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham C, et al. Characterization of a type IIb sodium-phosphate cotransporter from zebrafish (Danio rerio) kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F727–F736. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00356.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nalbant P, et al. Functional characterization of a Na+ phosphate cotransporter (NaPi-II) from zebrafish and identification of related transcripts. J Physiol. 1999;520(Pt 1):79–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sures B. Accumulation of heavy metals by intestinal helminths in fish: an overview and perspective. Parasitology. 2003;126(Suppl):S53–S60. doi: 10.1017/s003118200300372x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu CW. Lin KH. Jang CS. Tissue accumulation of arsenic compounds in aquacultural and wild mullet (Mugil cephalus) Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2006;77:36–42. doi: 10.1007/s00128-006-1029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedlar RM. Klaverkamp JF. Accumulation and distribution of dietary arsenic in lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) Aquat Toxicol. 2002;57:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0166-445x(01)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alquezar R. Markich SJ. Booth DJ. Metal accumulation in the smooth toadfish, Tetractenos glaber, in estuaries around Sydney, Australia. Environ Pollut. 2006;142:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattusch J, et al. Determination of arsenic species in water, soils and plants. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2000;366:200–203. doi: 10.1007/s002160050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, et al. Mammalian glucose permease GLUT1 facilitates transport of arsenic trioxide and methylarsonous acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin J, et al. Arsenic detoxification and evolution of trimethylarsine gas by a microbial arsenite S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2075–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506836103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vahter M. Envall J. In vivo reduction of arsenate in mice and rabbits. Environ Res. 1983;32:14–24. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(83)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Styblo M, et al. The role of biomethylation in toxicity and carcinogenicity of arsenic: a research update. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl 5):767–771. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]