Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal recessive genetic disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene. The gene product is a PKA-regulated anion channel that is important for fluid and electrolyte transport in the epithelia of lung, gut, and ducts of the pancreas and sweat glands. The most common CFTR mutation, ΔF508, causes a severe, but correctable, folding defect and gating abnormality, resulting in negligible CFTR function and disease. There are also a large number of rare CF-related mutations where disease is caused by CFTR misfolding. Yet the extent to which defective biogenesis of these CFTR mutants can be corrected is not clear. CFTRV232D is one such mutant that exhibits defective folding and trafficking. CFTRΔF508 misfolding is difficult to correct, but defective biogenesis of CFTRV232D is corrected to near wild-type levels by small-molecule folding correctors in development as CF therapeutics. To determine if CFTRV232D protein is competent as a Cl− channel, we utilized single-channel recordings from transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells. After PKA stimulation, CFTRV232D channels were detected in patches with a unitary Cl− conductance indistinguishable from that of CFTR. Yet the frequency of detecting CFTRV232D channels was reduced to ∼20% of patches compared with 60% for CFTR. The folding corrector Corr-4a increased the CFTRV232D channel detection rate and activity to levels similar to CFTR. CFTRV232D-corrected channels were inhibited with CFTRinh-172 and stimulated fourfold by the CFTR channel potentiator VRT-532. These data suggest that CF patients with rare mutations that cause CFTR misfolding, such as CFTRV232D, may benefit from treatment with folding correctors and channel potentiators in development to restore CFTRΔF508 function.

Keywords: corrector, potentiator, patch clamp

cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene (19). The gene product is a PKA-regulated anion channel and member of the large family of ATP-binding cassette transporters (18). Located in the apical membrane of various epithelia, this channel is responsible for Cl− and HCO3− transport, which is vital for epithelial fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Defective CFTR channel function in CF airways impairs mucous hydration and the ability to expel inhaled pathogens effectively (8, 21). Consequently, the unrelenting airway infection and inflammation result in progressive lung disease and are responsible for the majority of CF morbidity and mortality.

More than 1,000 disease-associated CFTR mutations have been identified. The most common mutation, CFTRΔF508, causes protein misfolding and channel gating defects, which together result in a severely reduced level of apical epithelial anion transport (21). Around 70% of CF patients of European origin are homozygous for the CFTRΔF508 mutation, but there remains a significant number of patients that are compound heterozygotes who inherit the ΔF508 allele along with a different rare mutant allele (3).

An approach to treat CF is correction of the conditional misfolding of CFTRΔF508 (4); yet drugs that accomplish this task are still in development (15). Interestingly, some disease-causing mutations in CFTR elicit folding defects that are less severe and much easier to correct than those caused by ΔF508 (9). Thus functional correction of the protein encoded by mutant alleles other than CFTRΔF508 in compound heterozygous CF patients might be an avenue to treatment.

The function of mutant CFTR can be restored, at least partially, with small molecules, termed “correctors,” which promote proper folding, or “potentiators,” which stimulate activity of mutant channels at the cell surface (23). Interestingly, some of the folding correctors that have been developed and are in use as tool compounds are not specific for the ΔF508 mutation and act to correct misfolding of a number of different CFTR mutants (9). However, the extent to which misfolding of rare CFTR mutant alleles can be corrected and the activity of the corrected mutant channel are just beginning to be investigated.

To address this issue, we screened a collection of CFTR mutants that have single amino acid substitutions in different subdomains for correction of misfolding by the small molecule N-(2–5-chloro-2-methoxyphenylamino)4′-methyl[4,5′′bithiazolyl-2′-yl]-benzamide (Corr-4a) (9). Corr-4a had modest effects on misfolding of most mutants tested but could correct misfolding of CFTRV232D to wild-type levels in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells. CFTRV232D is a rare CF-causing mutation located in the fourth transmembrane (TM)-spanning domain of the channel protein and is prevalent in CF patients of Spanish origin (2). The folding defect caused by the V232D mutation appears to be due to the introduction of a charged residue into a region of CFTR that is embedded in the lipid bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (17, 24). Since the folding defect in CFTR caused by the V232D mutation is correctable to wild-type levels, CF patients with this allele may benefit from treatment with folding correctors. However, for this to be the case, the corrected protein must function effectively as a PKA-activated anion channel.

Utilizing the patch-clamp technique for direct measurement of the mutant protein's single-channel behavior, we report on the functional properties of CFTRV232D. We found that the folding defect exhibited by CFTRV232D is not stringent and that a small portion of this protein can fold, accumulate, and function at the cell surface. Treatment with Corr-4a increased CFTRV232D protein expression and channel activity to levels that were similar to those of CFTR. Moreover, 4-methyl-2-(5-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenol (VRT-532), a channel potentiator (27), reversibly increased CFTRV232D channel activity in perfused inside-out patches. Thus CF caused by defective folding of rare CFTR mutants might be treated with existing CFTR modulators.

METHODS

Plasmids, antibodies, and reagents.

CFTR expression plasmids pcDNA3.1(+)-CFTR and pcDNA3.1(+)-CFTRV232D have been described previously (9). Antibodies used in this study were as follows: α-CFTR MM13-4 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and α-tubulin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Corr-4a and VRT-532 were provided by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Dr. Robert J. Bridges (Rosalind Franklin University, Chicago, IL).

Cell culture and transfection.

HEK-293 cells were obtained from Agilent (Cedar Creek, TX; formerly Stratagene) and maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin; Invitrogen) at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell transfections were performed using Effectene reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Analysis of CFTR steady-state levels.

Steady-state levels of CFTR and CFTRV232D protein were determined by Western blot analysis. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-CFTR or pcDNA3.1(+)-CFTRV232D. Transfected cells were allowed to recover for ∼18 h before addition of DMEM (10% FBS and antibiotics) supplemented with VRT-532 (10 μM), Corr-4a (5 μM), or vehicle [0.1% (vol/vol) DMSO]. The harvested cells were diluted with 2× SDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 0.05% bromphenol blue, 20% glycerol, complete protease inhibitor cocktail, and β-mercaptoethanol; Roche, Indianapolis, IN), sonicated, and heated at 37°C; then the proteins were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were probed with α-CFTR antibody. α-Tubulin antibody was used to indicate loading controls.

Fluorescence measurements.

Macroscopic function of CFTR and of the indicated mutants was evaluated in Cos-7 cells using the 6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl)quinolinium (SPQ) fluorescence assay (12). Cells were seeded into a six-well plate at a density of 2 × 106 cells/well and transfected with 1 μg of CFTR pcDNA3.1 constructs using Effectene transfection reagents. Transfected cells were replated into a clear-bottom, black 96-well plate and treated with 5 μM Corr-4a for 18 h. Cells were loaded with 10 mM SPQ (Sigma) via hypotonic bath solution containing (in mM) 67.5 NaNO3, 0.5 CaNO3, 1.2 K2HPO4, 0.3 KH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, 5 glucose, 2.5% DMSO (vol/vol), and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, for 20 min at 37°C. The cells were loaded with iodide using bath solution containing (in mM) 135 NaI, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 20 HEPES, pH 7.4, for 5 min at 37°C. Iodide buffer was replaced by halide-free bath solution containing (in mM) 135 NaNO3, 1 CaNO3, 2 MgSO4, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 20 HEPES, pH 7.4, and incubated for 5 min. CFTR was activated by the addition of 125 μM forskolin, 1 mM IBMX, and 500 μM dibutyryl-cAMP. Fluorescence (excitation wavelength=326 nm, emission wavelength=455 nm) was measured at 0 s and up to 240 s post-CFTR activation in 60-s intervals using a microplate reader (FlexStation-3, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Patch-clamp electrophysiology.

Channel activity from cell-attached and excised inside-out patches configured from HEK-293 cells was studied. Analog signals (EPC-7, List Medical, Darmstadt, Germany) were filtered at 50–100 Hz (−3 dB, 4-pole Bessel, Ithaco filter), digitized at 1 kHz (16-bit, ITC, Instrutech, Long Island, NY), and acquired with a personal computer using HEKA-PULSE acquisition software (Bruxton, Seattle, WA). Patch pipettes (borosilicate; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) were fabricated from thin-walled glass using a three-stage pull routine (DMZ Universal Puller, Zeitz Instruments) and fire-polished to 8.6 ± 0.1 (SE) mΩ (n=136) resistance with the patch solutions (see below). A Ag-AgCl electrode connected to the bath chamber via a 3% agar bridge containing 1 M KCl served as the ground electrode. Experiments were performed at ∼23°C.

Bath and pipette patch solutions.

Bath solution contained (in mM) 150 N-methyl-d-glucamine-HCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, and 10 TES titrated to pH 7.30 with 1 N NaOH. The pipette solution consisted of the bath solution supplemented with 0.1 mM CaCl2 to promote sealing of the patch pipette to the cell membrane. CFTR activity was stimulated for up to 1 h prior to patch-clamp experiments using a PKA agonist cocktail consisting of 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (300 μM), forskolin (300 μM), and IBMX (10 μM) contained in bath solution. For excised inside-out patches, the bath solution was supplemented with 1–2 mM MgATP.

Patch-clamp protocols and data analysis.

Channel trafficking efficiency was estimated from the number of cell-attached patches containing channel openings of 0.2 pA (current amplitude measured for CFTR at +40 mV, pipette potential) divided by the total number of patches, with and without detectable channel openings, from 5-min recordings.

Current-voltage curves were constructed from unitary current amplitudes measured in excised patches at various holding voltages (range −60 to +40 mV). Slope conductance was obtained from linear regression of the current-voltage relationship. Unitary current amplitudes and channel activity were quantified from Gaussian fits to all-points current histograms using commercial software (TAC and TACFit, Bruxton). Channel activity was measured in 30-s sweeps and averaged over the total number of sweeps (3–5 min) and is reported from active patches as the NPo product

| (1) |

where N is the number of functional channels, Po is the channel open probability, nt, is the total number of samples in the histogram, iu is the unitary current amplitude, Yj is the number of samples within bin j, Ij is the current in bin j, and Iz is the offset current (6).

Patch perfusion of channel modulators.

Excised inside-out patches were configured from HEK-293 cells pretreated with Corr-4a (24–30 h, 5 μM) and PKA agonist cocktail (0.2–1 h). Patch perfusion and solution exchange were achieved using a commercial solution exchanger (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) with exchange time (t10–90%)=70 ms, as previously described (5). Corr-4a, VRT-532, and CFTRinh-172 (Sigma) stock solutions (in DMSO) were diluted to the indicated concentrations in bath solution and used within 3 h of preparation. DMSO [final concentration 0.01% (vol/vol)] was included in all patch bath solutions. Macroscopic currents were measured from inside-out macropatches configured with large-diameter pipettes (resistance ∼5 mΩ). The time course of the potentiator-modulated current was fitted with a single-exponential model equation for a reversible drug-receptor interaction (11)

| (2) |

where I is macroscopic current, Ic is baseline current, Ipot is potentiator-stimulated current, and τ is time constant. Model parameters were given starting estimates, and data convergence was performed automatically using the Levenburg-Marquardt minimization of nonlinear least-squares algorithm (Table Curve 2D, SPSS).

Statistics.

Results are reported as means ± SE, with n=number of experiments, unless otherwise stated. Statistical comparisons of SPQ fluorescence and patch-clamp data were made using ANOVA followed by Tukey's test for evaluating the effect of genetic construct and drug on the mean data. Statistics were computed with SigmaStat software (SPSS, version 2.03). P < 0.050 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

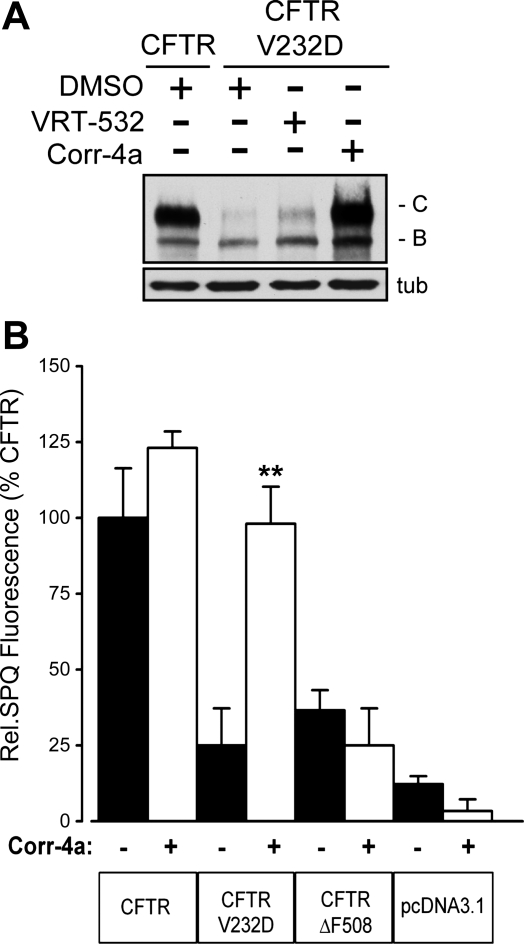

CFTRV232D protein expression was studied in transiently transfected HEK-293 cells. A representative Western blot analysis of cell extracts is shown in Fig. 1A. Band B depicts the low-molecular-weight, immature protein product after CFTR core glycosylation in the ER. Band C depicts the high-molecular-weight mature CFTR protein that accumulates after complex glycosylation in the trans-Golgi network. Compared with CFTR, only a small pool of CFTRV232D accumulated as band C protein (Fig. 1A). Yet treatment of cells with Corr-4a (24 h, 5 μM) led to accumulation of CFTRV232D band C to levels comparable to CFTR. In related studies, we showed in pulse-chase experiments that Corr-4a increased accumulation of CFTRV232D due to an increase in folding efficiency and not increased expression (9). In addition, we found that VRT-532, a compound identified as a potentiator of CFTR Po, was associated with a modest increase in CFTRV232D band C expression, as was reported for CFTRΔF508 (27). Importantly, the CFTRV232D trafficking defect was surmounted by Corr-4a treatment, with the folded protein achieving CFTR expression levels in HEK-293 cells.

Fig. 1.

Folding-corrected CFTRV232D protein expression and function. A: Western blot analysis of CFTR and CFTRV232D protein expression. Immature and mature glycosylated forms are represented by bands B and C, respectively. N-(2–5-chloro-2-methoxyphenylamino)4′-methyl[4,5′′bithiazolyl-2′-yl]-benzamide (Corr-4a) enhanced accumulation of CFTRV232D band C protein relative to vehicle-treated (DMSO) control. A modest increase in band C formation was also apparent with 4-methyl-2-(5-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenol (VRT-532) treatment. Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 expression vector ± CFTR or CFTRV232D and pretreated overnight with Corr-4a (5 μM), VRT-532 (10 μM), or DMSO before lysis and protein blotting; α-tubulin (tub) was used to confirm equal protein loading across lanes. B: 6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl)quinolinium (SPQ) fluorescence from transfected Cos-7 cells. Cells were pretreated (24 h) with Corr-4a (5 μM, open bars) or DMSO (filled bars). Fluorescence was measured every 60 s following cell stimulation with PKA agonist cocktail. Steady-state fluorescence was plotted from measurements taken 240 s after PKA agonist cocktail addition. Data were normalized to CFTR fluorescence at 240 s. Values are means ± SE (n=3). **P=0.001 vs. DMSO alone. SPQ fluorescence of Corr-4a-pretreated CFTRV232D-transfected cells was not statistically different from that of DMSO-treated CFTR-transfected cells (P=1.00). Mean fluorescence signals between treatments and groups from CFTRΔF508 (Corr-4a, DMSO), CFTRV232D (DMSO), and pcDNA3.1 (Corr-4a, DMSO) were not significantly different (P=0.33–0.98). Cells were cultured and maintained at 37°C continuously throughout the experiments.

We next examined CFTRV232D channel function compared with CFTR, with and without Corr-4a treatment (Fig. 1B). Channel-mediated halide efflux was estimated in Cos-7 cells using the SPQ fluorescence assay (12). SPQ fluorescence measured 240 s after cAMP-dependent stimulation of CFTR channels was almost fivefold higher than CFTRV232D (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the low-level accumulation of maturely glycosylated CFTRV232D protein (Fig. 1A), the SPQ fluorescence in cells that expressed CFTRV232D was not significantly different from background (pcDNA3.1). Strikingly, Corr-4a treatment increased CFTRV232D-mediated SPQ fluorescence to levels indistinguishable from that of CFTR in untreated cells (Fig. 1B). Corr-4a did not significantly increase CFTR-mediated fluorescence over the vehicle control, however.

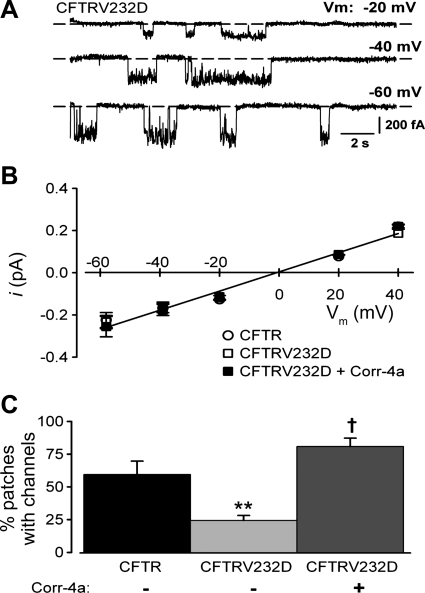

The lack of functional evidence for CFTRV232D expression in the SPQ assay of untreated cells prompted us to use the patch-clamp technique to investigate the mutant protein's single-channel characteristics. As shown in Fig. 2A, open channel gating transitions were detected in an excised patch from a HEK-293 cell that was pretreated with PKA agonist cocktail. Channel open transitions were measured over a wide range of voltages, and the unitary current amplitudes were not different from those of CFTR channels or from CFTRV232D channels previously exposed to Corr-4a (Fig. 2B). As we will show, channel activity from Corr-4a-treated channels was reversibly blocked by the CFTR inhibitor CFTR172-inh. Thus CFTRV232D is capable of folding and reaching the membrane surface, where it is functional and displays a Cl− conductance that is indistinguishable from CFTR.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of patches containing CFTRV232D channels is increased with Corr-4a. A: basal single-channel currents recorded in an excised inside-out patch from a CFTRV232D-transfected HEK-293 cell. Currents were measured at different membrane voltages (Vm). Dashed horizontal lines depict 0-current level. B: current-voltage (i-V) relationship. Unitary current amplitudes were compared with those from CFTR- and CFTRV232D-transfected cells pretreated with Corr-4a (5 μM, 24 h). Unitary Cl− currents from CFTRV232D-transfected cells (±Corr-4a) were indistinguishable from those recorded from CFTR-transfected cells (2–5 measurements/group). Slope conductance was 5 pS [linear regression, solid line (r2=0.984)]. Current reversed at Vm=3 mV, which is close to the theoretical Nernst potential (0 mV) for symmetrical Cl− activities used in bath and pipette solutions. C: percentage of cell-attached patches detected with channel activity. CFTR channels were detected in 59 ± 10% of patches (44 recordings from 11 experiments). CFTRV232D channels were detected at a relatively reduced frequency [24 ± 3%, 62 recordings from 10 experiments (**P=0.008 vs. CFTR)]. Corr-4a increased the frequency of CFTRV232D-active patches to 81 ± 6% [20 recordings from 5 experiments (†P < 0.001 vs. CFTRV232D)] and to a level that was not significantly different from CFTR (P=0.251). Patch recordings were made from cells (23°C) within 1 h of stimulation with PKA agonist cocktail. Bath solution for excised patch experiments was supplemented with MgATP (2 mM).

However, when the extent to which CFTRV232D channels reached the membrane surface was evaluated, their frequency of expression was much reduced compared with CFTR. CFTR channel openings were detected in ∼60% of patches (26 of 44 recordings), whereas CFTRV232D channel openings were found in only ∼24% of patches (15 of 62 recordings; Fig. 2C). Treatment of cells with Corr-4a overnight increased the CFTRV232D channel detection frequency by nearly fourfold, to a level that was not significantly different from CFTR.

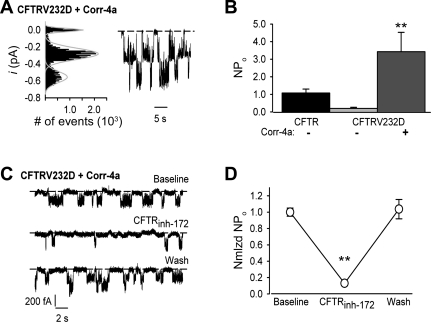

A representative current trace of channel activity recorded from a cell pretreated with Corr-4a is shown in Fig. 3A. Visual inspection of the record revealed multiple overlapping channel events, and analysis of the current histogram confirmed the presence of at least two channels in the patch (Fig. 3A). As summarized in Fig. 3B, CFTRV232D activity from Corr-4a-pretreated patches was increased by 3- to 17-fold over the activity of wild-type and CFTRV23D channels from untreated patches, respectively. Moreover, channel activity was blocked by the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172. CFTRinh-172 (5 μM) perfused on the intracellular surface of inside-out patches reduced channel activity, as shown in Fig. 3C. CFTRinh-172 inhibition of channel activity was completely reversible. After 1 min of inhibitor washout, channel activity returned to baseline (Fig. 3C). Summary data from these experiments are shown in Fig. 3D. CFTRinh-172 decreased channel activity by ∼87%. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that CFTRV232D is highly amenable to functional correction in HEK-293 cells.

Fig. 3.

Corr-4a increases CFTRV232D channel activity. Channel activity is reported as NPo (Eq. 1) and measured from excised patches detected to contain channels with a unitary current amplitude shown in Fig. 2B (Vm=−40 mV). A: right, patch-clamp record of multiple active CFTRV232D channels obtained from a HEK-293 cell that was pretreated with 5 μM Corr-4a for ∼24 h; left, all-points current histogram showing 3 well-resolved peaks at 0 pA (closed), −0.28 pA (single channel), and −0.56 pA (2 simultaneously open channels). Gaussian fits to the current histogram are shown as gray curves. B: channel activity summary results. Corr-4a treatment increased CFTRV232D activity 17-fold over baseline activity [from NPo=0.2 ± 0.1 (n=5) to NPo=3.4 ± 1.1 (n=9) (**P=0.026)] and ∼3-fold over CFTR [NPo=1.1 ± 0.2, n=11 (P=0.047)]. NPo from CFTRV232D and CFTR were not significantly different (P=0.706). C: CFTRV232D activity is reversibly inhibited by CFTR172-inh. CFTRV232D single-channel currents were recorded during bath perfusion of an excised inside-out patch. Channel activity (top trace, Baseline) decreased in bath solution containing CFTR172-inh (5 μM, 20–60 s perfusion; middle trace) and fully recovered 30–60 s after CFTR172-inh washout (bottom trace). D: summary results of CFTR172-inh block of CFTRV232D activity. CFTR172-inh (5 μM) inhibited NPo by 87% [CFTR172-inh normalized (Nmlzd) NPo=0.13 ± 0.03 vs. Baseline Nmlzd NPo=1.00 ± 0.05 (**P < 0.05)] and was completely reversible [Wash Nmlzd NPo=1.04 ± 0.12 vs. Baseline Nmlzd NPo (P=0.940)]. Channel activity (NPo) was averaged over 3 sweeps (10 s/sweep), and all channel activity was normalized to average baseline NPo for each of 3 experiments. Channel activity was recorded (Vm=−60 mV) using HEK-293 cells pretreated with Corr-4a (5 μM, 24 h) and as described in Fig. 2 legend.

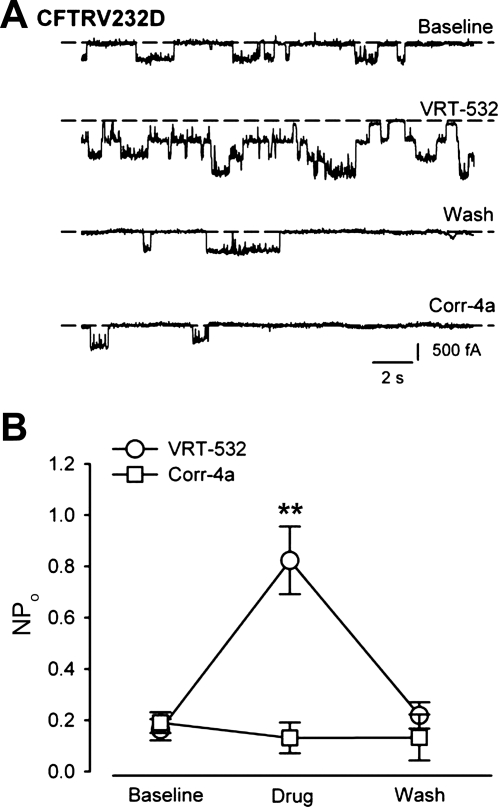

Single-channel recordings (Fig. 2), which are far more sensitive than the SPQ assay (Fig. 1B), suggest that the small fraction of CFTRV232D protein observed to fold (Fig. 1A) exhibits bona fide Cl− channel activity. A number of control experiments indicated that Cl− currents detected in HEK-293 cells that express uncorrected CFTRV232D protein do, in fact, originate from this channel. HEK-293 cells express a volume-regulated Cl− channel (10), but background channel transitions were detected infrequently in untransfected cells. In 2 of 11 cell-attached patch recordings of 3–10 min duration, a total of 4 channels with amplitude of ∼0.4 pA and open dwell times of 1–5 s (NPo < 0.03) were detected (data not shown). Channel activity was transient, with detection occurring within the 1st min of seal formation and subsiding within 3 min of recording. Similar channel events were also detected in patches from untransfected cells pretreated with Corr-4a (data not shown). Because of such few channel openings, we were unable to characterize unitary conductance. In contrast, channel activity from CFTRV232D-transfected cells was stable for the 3- to 10-min recording window (Figs. 4 and 5). Thus, given their paucity of detection and insensitivity to Corr-4a, background channels were deemed unlikely to confound interpretation of results on CFTRV232D functional expression.

Fig. 4.

CFTRV232D activity is stimulated by the potentiator VRT-532. A: representative CFTRV232D single-channel current traces during bath perfusion of an inside-out patch. Baseline channel activity was recorded for 5 min. Baseline trace was obtained at 4.6–5 min. With exposure to 10 μM VRT-532 (20–40 s), as many as 3 open channels were detected. Only single-channel current transitions were detected following VRT-532 washout (Wash, 40–60 s). Patch perfusion of 2 μM Corr-4a (40–60 s) resulted in no discernable increase of channel activity. B: summary data of potentiator action on CFTRV232D activity. VRT-532 increased CFTRV232D NPo 4-fold over baseline channel activity [from 0.2 ± 0.0 to 0.8 ± 0.1, n=9 (**P < 0.001)] and was completely reversible (Wash NPo=0.2 ± 0.1, n=8). Channel activity measured in the presence of Corr-4a was not significantly different from baseline activity [Corr-4a NPo=0.1 ± 0.1, n=6 (P=0.43)]. Channel recordings were made using HEK-293 cells, as described in Fig. 3C legend.

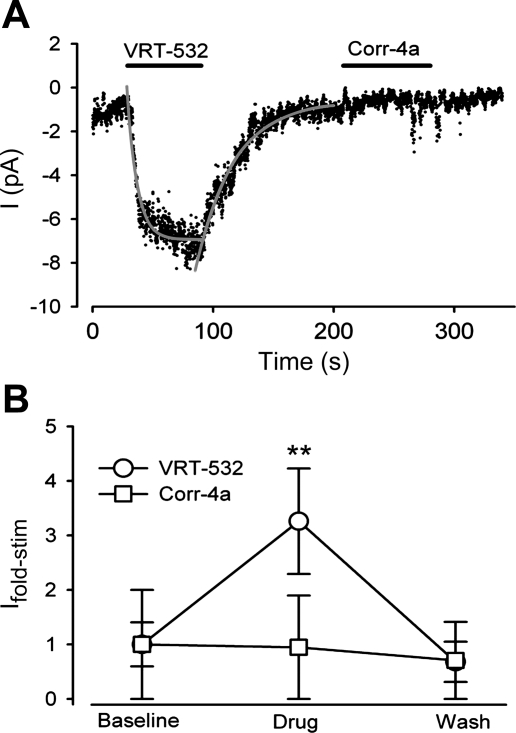

Fig. 5.

Macroscopic kinetics and magnitude of the potentiator-stimulated CFTRV232D currents. Macroscopic Cl− currents from excised macropatches were measured. A: representative current trace recorded at −40 mV. After baseline current measurement (0–40 s), VRT-532 (10 μM) perfusion resulted in a rapid increase of the inward current, which stabilized over 60 s and then returned to baseline following potentiator washout. Gray curves depict single-exponential fits to the time course of current stimulation [mean time constant (τon)=6.2 ± 0.9 s, n=8] and recovery after VRT-532 washout from the patch (τoff=24.0 ± 2.2 s, n=5). In contrast, Corr-4a (2 μM) was not found to stimulate current. B: summary of fold stimulation of current (Ifold-stim) achieved with CFTR modulators. Ifold-stim was increased 3.3 ± 1.0-fold with VRT-532 [10 μM, n=9 (**P < 0.050)] but was insensitive to Corr-4a [2 μM, n=6 (P=0.143)]. Currents were recorded using HEK-293 cells, as described in Fig. 4 legend.

Since CFTRV232D channels could reach the plasma membrane, we asked if channel activity could be stimulated by small-molecule potentiators of CFTR gating (25). As with the experimental protocol in Fig. 3C, we used a perfused patch assay, and cells were pretreated with Corr-4a to enhance channel detection efficiency. Figure 4A shows traces from a representative single-channel recording before, during, and after perfusion of an excised patch with VRT-532. CFTRV232D activity was readily increased within 40 s of VRT-532 exposure, and activity returned to near-baseline level upon potentiator washout. In contrast, Corr-4a was not found to stimulate CFTRV232D activity at a concentration comparable to that which promoted protein folding. Summary data from these experiments are shown in Fig. 4B. VRT-532 reversibly increased channel activity (NPo) 4.2-fold over the baseline level.

The fast stimulation and reversibility of VRT-532 action on CFTRV232D channel activity prompted us to measure the time course and magnitude of the potentiator-stimulated currents. Excised macropatches from Corr-4a-pretreated HEK-293 cells were configured using low-resistance (∼5 mΩ) pipettes. A representative current trace is shown in Fig. 5A. Baseline current was monitored for 40 s during patch perfusion. When the perfusate was switched to VRT-532-containing bath solution, a rapid increase in current was observed. The time course of the current change was fitted with a single-exponential equation (Eq. 2) with a time constant of 8 s. Once the current had stabilized (during ∼45 s of VRT-532 exposure), the perfusate was switched to VRT-532-free solution and the current decayed back to the baseline level (time constant=31 s). VRT-532 reversibly stimulated the CFTRV232D-mediated current 3.3-fold (Fig. 5B), which is in good agreement with current stimulation predicted from the NPo results. The monoexponential time course of the reversible stimulation of CFTRV232D current by VRT-532 is consistent with kinetics of a single drug-receptor interaction (11), although indirect effects (e.g., via drug-lipid partitioning) cannot be excluded (14). Taken together, CFTRV232D functional expression can be enhanced via folding correction in the ER and stimulation of channel activity at the cell surface.

DISCUSSION

CFTRV232D is a rare CF-causing mutation (2) that impairs protein folding and trafficking to the surface membrane (9). The frequency of CFTRV232D occurrence is low in the global population of CF patients but is considered common in cohorts of Spanish CF patients (3). Yet the mechanism by which the V232D mutation causes CF is not well documented, and whether patients with this mutation can be treated with modulators of CFTR folding and channel activity is not clear. V232 is located in TM region 4 of membrane-spanning domain 1 and, therefore, is predicted to be embedded in the lipid bilayer. The V232D mutation is proposed to cause aberrant hydrogen bonding between TM4 and adjacent TM segments in CFTR (24). This folding defect may explain why the vast majority of CFTRV232D is selected for premature degradation and fails to reach the cell surface. Yet a small quantity of CFTRV232D can fold and accumulate at the cell surface. Interestingly, single-channel recordings demonstrate that CFTRV232D is a functional Cl− channel. In fact, on the basis of the unitary Cl− conductance and activity, CFTRV232D function is indistinguishable from CFTR. Nevertheless, the number of CFTRV232D channels that reach the cell surface is low compared with CFTR. Therefore, reduced cell surface expression of CFTRV232D is likely to decrease cAMP-dependent apical epithelial Cl− conductance in epithelia, which can explain the CF disease caused by this mutation.

Interestingly, we found that CFTRV232D Cl− channel activity can be restored to high levels in HEK-293 cells by a small molecule, Corr-4a, that was identified in efforts to correct the misfolding of CFTRΔF508 (16). In addition, activity of CFTRV232D can also be enhanced by a potentiator, VRT-532, which is a member of a class of compounds developed to increase the activity of cell surface-localized CFTR gating mutants (26). Thus CF patients that harbor low-frequency mutations, such as V232D, might be treated with small molecules that correct CFTR misfolding or potentiate CFTR channel activity.

Why is it that Corr-4a has very modest effects on correction of CFTRΔF508 misfolding but can dramatically improve folding and increase the detection frequency and Cl− channel activity of CFTRV232D to levels comparable to CFTR? The answer to this question is not clear, but it appears that the ΔF508 mutation causes global defects in CFTR that involve misfolding of nucleotide binding domain 1 and failure of nucleotide binding domain 1 to make proper intramolecular contacts required to stabilize the native CFTR structure (7, 13, 20, 22, 25). Studies on the mechanism of Corr-4a action suggest that it acts to stabilize the TM regions of CFTR (9, 28). In doing so, Corr-4a may prevent the V232D mutation from causing the aberrant hydrogen bonding between TM segments in the bilayer proposed to cause premature degradation of CFTRV232D (24). However, even though Corr-4a may stabilize nascent CFTRΔF508, it appears incapable of correcting the global assembly defects caused by ΔF508 and is ineffective as a folding corrector for this mutant.

Corr-4a can increase the cell surface expression and single-channel activity of CFTRV232D to levels that resemble those of wild-type CFTR. Data from comparison of corrected CFTRV232D and CFTR activity in whole cells, channel detection frequency, and the NPo from excised patches configured from cells exposed to PKA agonist cocktail support this conclusion. However, it is not yet clear that the open and closed channel dwell times, PKA sensitivity, and ATP dependence on gating between CFTRV232D and CFTR are the same.

An interesting feature of CFTRV232D is that the folding defect it exhibits is not stringent and pools of it escape the ER and reach the cell surface of HEK-293 cells, where it is competent as a Cl− channel. The extent to which this occurs in epithelial cells in lungs of CF patients is not clear. Yet we found that the activity of CFTRV232D in excised patches was potentiated by VRT-532. Thus, if a sufficient quantity of CFTRV232D were to reach the apical surface of lung epithelia, patients with this mutation might be treated with a potentiator of CFTR channel activity (1).

ΔF508 is the most common CF-causing mutant; yet up to 30% of CF patients are compound heterozygotes who inherit a copy of ΔF508 and a different less-common allele. Restoration of CFTRΔF508 function is clearly achievable; yet our studies on CFTRV232D indicate that less-common CF-causing mutants might be more amenable to functional correction. Therefore, it is important to identify additional CFTR mutants that behave similar to CFTRV232D and identify CF patient populations that might be treated with small molecules developed to correct CFTRΔF508 misfolding or potentiate channel activity (e.g., CFTRG551D). These data will open the door for individualized treatment of subpopulations of CF patients who inherit mutant forms of CFTR that are amenable to functional correction.

GRANTS

Funding for this work was provided by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Grant GROVEE07FO (D. E. Grove) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant RO1 GM-56981 (D. M. Cyr).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Andrei Aleksandrov for helpful suggestions with experiments, Hong Yu Ren for cell cultures, and Holly B. Beasley for assistance with pipette resistance summary data.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accurso FJ, Rowe SM, Clancy JP, Boyle MP, Dunitz JM, Durie PR, Sagel SD, Hornick DB, Konstan MW, Donaldson SH, Moss RB, Pilewski JM, Rubenstein RC, Uluer AZ, Aitken ML, Freedman SD, Rose LM, Mayer-Hamblett N, Dong Q, Zha J, Stone AJ, Olson ER, Ordonez CL, Campbell PW, Ashlock MA, Ramsey BW. Effect of VX-770 in persons with cystic fibrosis and the G551D-CFTR mutation. N Engl J Med 363: 1991–2003, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alonso MJ, Heine-Suner D, Calvo M, Rosell J, Gimenez J, Ramos MD, Telleria JJ, Palacio A, Estivill X, Casals T. Spectrum of mutations in the CFTR gene in cystic fibrosis patients of Spanish ancestry. Ann Hum Genet 71: 194–201, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bobadilla JL, Macek M, Jr, Fine JP, Farrell PM. Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations—correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum Mutat 19: 575–606, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown CR, Hong-Brown LQ, Welch WJ. Correcting temperature-sensitive protein folding defects. J Clin Invest 99: 1432–1444, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caldwell RA, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Neutrophil elastase activates near-silent epithelial Na+ channels and increases airway epithelial Na+ transport. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L813–L819, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dempster J. Computer Analysis of Electrophysiological Signals. New York: Academic, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Du K, Sharma M, Lukacs GL. The ΔF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 17–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gregory RJ, Cheng SH, Rich DP, Marshall J, Paul S, Hehir K, Ostedgaard L, Klinger KW, Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Expression and characterization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Nature 347: 382–386, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grove DE, Rosser MF, Ren HY, Naren AP, Cyr DM. Mechanisms for rescue of correctable folding defects in CFTRΔF508. Mol Biol Cell 20: 4059–4069, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helix N, Strobaek D, Dahl BH, Christophersen P. Inhibition of the endogenous volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) in HEK293 cells by acidic di-aryl-ureas. J Membr Biol 196: 83–94, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Illsley NP, Verkman AS. Membrane chloride transport measured using a chloride-sensitive fluorescent probe. Biochemistry 26: 1215–1219, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lukacs GL, Mohamed A, Kartner N, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. Conformational maturation of CFTR but not its mutant counterpart (ΔF508) occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and requires ATP. EMBO J 13: 6076–6086, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lundbaek JA, Koeppe RE, 2nd, Andersen OS. Amphiphile regulation of ion channel function by changes in the bilayer spring constant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15427–15430, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 373: 1891–1904, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pedemonte N, Lukacs GL, Du K, Caci E, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Small-molecule correctors of defective ΔF508-CFTR cellular processing identified by high-throughput screening. J Clin Invest 115: 2564–2571, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, Deber CM. Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 1760–1765, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riordan JR. CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 701–726, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245: 1066–1073, 1989. [Erratum. Science 245 (Sep): 1437, 1989.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosser MF, Grove DE, Chen L, Cyr DM. Assembly and misassembly of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: folding defects caused by deletion of F508 occur before and after the calnexin-dependent association of membrane spanning domain (MSD) 1 and MSD2. Mol Biol Cell 19: 4570–4579, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 352: 1992–2001, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serohijos AW, Hegedus T, Aleksandrov AA, He L, Cui L, Dokholyan NV, Riordan JR. Phenylalanine-508 mediates a cytoplasmic-membrane domain contact in the CFTR 3D structure crucial to assembly and channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3256–3261, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sloane PA, Rowe SM. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein repair as a therapeutic strategy in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 16: 591–597, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Therien AG, Grant FE, Deber CM. Interhelical hydrogen bonds in the CFTR membrane domain. Nat Struct Biol 8: 597–601, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thibodeau PH, Richardson JM, 3rd, Wang W, Millen L, Watson J, Mendoza JL, Du K, Fischman S, Senderowitz H, Lukacs GL, Kirk K, Thomas PJ. The cystic fibrosis-causing mutation ΔF508 affects multiple steps in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator biogenesis. J Biol Chem 285: 35825–35835, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, Gonzalez J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, Neuberger T, Olson E, Panchenko V, Rader J, Singh A, Stack JH, Tung R, Grootenhuis PD, Negulescu P. Rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1117–L1130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Bartlett MC, Loo TW, Clarke DM. Specific rescue of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator processing mutants using pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol 70: 297–302, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Correctors promote maturation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-processing mutants by binding to the protein. J Biol Chem 282: 33247–33251, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]