Abstract

Background

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) is a sensitive and non-invasive method for tracking the fate of transplanted islets and for early detection of graft rejection. The aim of this study was to investigate whether the early detection of rejection by BLI can aid in the timing of anti-lymphocyte serum (ALS) treatment for prolonging islet graft survival.

Methods

Transgenic islets (200/recipient) expressing the firefly luciferase from FVB/NJ strain (H-2q) mice were transplanted under the kidney capsule of streptozotocin-induced diabetic allogeneic Balb/c strain (H-2d) mice. BLI signals and serum glucose levels were measured daily after transplantation. Three groups of mice were transplanted: Group 1 recipients were untreated controls (n=12), Group 2 (n=8) received ALS treatment prior to transplant, and Group 3 (n=10) received ALS at a time post-transplant prompted by a reduction (<30%) in BLI signal intensity for two consecutive days.

Results

The rejection rates in groups 1, 2, and 3 were 92.3%, 88%, and 40%, respectively. The mean (± SE) time to graft loss from rejection in groups 1, 2 and 3 were 22.5 ±4.8, 29.2 ±9.9, and 53.5±17.9 days, respectively. Histologic analyses showed significant differences in T-cell infiltration at the graft site in controls and BLI prompted ALS treated recipients.

Conclusions

These results demonstrated that non-invasive imaging modalities of functional islet mass, such as BLI, can prompt the timing of treatment of islet allograft rejection, and that appropriate timing of ALS treatment of acute cellular rejection can prolong graft survival or protect the grafts from permanent loss.

Keywords: bioluminescence imaging, islet transplantation, rejection

INTRODUCTION

The recently reported multi-center trial of islet transplantation (1) revealed that this modality of treatment can successfully ameliorate long-term glycemic instability and severe hypoglycemic complications in select subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. However, insulin independence was usually not sustainable. Complete loss of islet allograft function occurs in approximately 25% of recipients within five years of the initial islet infusion. Islet allograft rejection is a possible cause of the progressive loss of graft function, although no detailed immunologic or histologic studies have been reported. Improvements in the current methods to promptly detect and treat islet graft rejection would be expected to favorably influence the long-term durability of islet transplantation in ameliorating type 1 diabetes.

In recent years, efforts have been made in developing non-invasive imaging modalities for monitoring islet mass after islet transplantation. The application of a bioluminescence imaging (BLI) system for real-time monitoring of transgenic islet grafts that constitutively express luciferase in syngeneic and allogeneic mouse islet transplantation models is one such example (2, 3). We have reported using the functional murine model that BLI is a sensitive imaging method for tracking the fate of islets after transplantation and for detecting early loss of functional islet mass caused by host allo-immune responses before overt metabolic dysfunction becomes evident (3). Similar observations have been reported in mouse cardiac transplantation models that demonstrate that the intensity of light emitted from luciferase-expressing cardiac grafts declined several days before the acute rejection of cardiac allografts (4).

In this study, we hypothesized that instituting T-cell depleting anti-rejection treatment at the time of declining BLI signal intensity expression by transplanted allogeneic islets would decrease the rate of islet loss from rejection and prolong islet graft survival. Anti-lymphocyte serum (ALS) is a polyclonal antibody with activity directed to both T cells and non-T-cells (5, 6). It nearly completely depletes T cells and approximately 80% of monocytes and natural killer cells by the second day of treatment (7). Because of the profound immunosuppressive effects, ALS has been used as a potent immunosuppressive drug in experimental (8) and clinical transplantation (9). ALS has previously been demonstrated to prolong islet graft survival in animal models of allogenic and xenogeneic islet transplantation (10–17). In these experiments, ALS was administered to recipient mice, either alone (10, 11) or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents (12–17).

To test this hypothesis, ALS was administered immediately after a significant decline in the graft BLI signal intensity. We have previously reported that the decline in BLI signal intensity is associated with histological evidence of a cellular rejection response (3). The outcomes of the experimental group were compared to that of untreated controls (natural history of the allo-immune response), and to that of islet graft recipients that received ALS at the time of islet implantation. The later served as a control for the timing of ALS treatment in protecting the islet allograft from an ongoing rejection reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

A transgenic mouse line, Tg(RIP-luc), on the FVB/NJ background (H-2q) contains the firefly luciferase gene under the regulation of a rat insulin promoter II (760bp) that specifically and constitutively express firefly luciferase in the pancreatic islet β-cell (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). FVB-Tg(RIP-luc) mice were used as islet donors in each transplant procedure. Wild-type male Balb/c (H-2d) mice were used as islet recipients (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). All strains were housed in a barrier facility at Northwestern University and were used at ages of 12–16 weeks. All procedures relating to the mice were approved by the Center for Comparative Medicine at Northwestern University and followed guidelines set by the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Diabetes Induction

Recipient mice were made diabetic by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of the pancreatic β-cell toxin streptozotocin (220mg/kg body weight, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.05M citric acid buffer (pH4.6). Mice that exhibited serum glucose levels greater than 300 mg/dL for at least two consecutive days were considered to be diabetic and were used as transplant recipients.

Islet Isolation

FVB-Tg(Rip-luc) mice were anesthetized via i.p. injection of 300 mg/kg of Avertin (2,2,2-Tribromoethanol, Sigma). A midline laparotomy was performed and a clamp was placed across the duodenum at the level of the common bile duct. The duct was then cannulated and a cold solution of collagenase (13.0mg per mouse; Type XI, Sigma) in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Gibco-BRL/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was injected into the duct. The distended pancreas was then removed and subjected to stationary digestion at 37°C for 15 minutes. The islets were purified from the digestate using a discontinuous dextran gradient (Sigma). Islets were hand-picked from the purification media, quantified, and placed in HBSS before transplantation.

Islet Transplantation and Functional Outcome

Recipient mice were anesthetized by Avertin as described above. For islet transplantation procedures under the kidney capsule (KC), the left kidney was exposed through a left lateral abdominal incision. A small nick was made in the capsule and approximately 50μl of Hank’s balanced salt solution containing the 200 FVB-Tg(RIP-luc) islets was injected via a custom-designed micro-pipetting device. The abdominal incision was closed in two layers with a 5-0 absorbable Maxon suture (Davis & Geck, Danbury, CT). Acceptance of an islet graft was defined by induction and persistence of normoglycemia (non-fasting blood glucose levels <200mg/dL) and rejection as reversion to glucose levels greater than 250mg/dL after a period of transient normoglycemia.

Bioluminescence Imaging

In preparation for BLI photon detection, recipient mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isofluorane in air. The methodology of BLI has been previously described (2). When anesthesia was induced, 200mg/kg body weight of substrate luciferin potassium salt (Molecular Therapeutics, Ann Arbor, MI) was administered by a single i.p. injection. The mice were placed into the camera chamber, where a controlled flow of 2.0% isofluorane in air was administered through a nose cone via a gas anesthesia system designed to work in conjunction with the bioluminescent imaging system (IVIS 200; Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Photon measurement was obtained precisely and consistently at 12 minutes after injection of luciferin, and BLI acquisition time was exactly 1 minute. A grayscale body image was collected and overlaid by a pseudo-color image representing the spatial distribution of the detected photons. Luminescence was quantified as the sum of all detected photons per second within a constant region of interest for each transplant site with use of the Living-Image software (Xenogen, Alameda, CA).

Treatment with ALS

For each transplant recipient, islet graft bioluminescent signal intensity and non-fasting serum glucose levels were measured daily after transplantation. Group 1 control mice received two i.p. doses of saline (at transplant days −2 and 0) instead of ALS. Group 2 recipients received two doses of ALS [0.5ml rabbit anti-mouse lymphocyte serum (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation)] at transplant days −2 and 0. In Group 3 ALS (same dose as Group 2) was administered at a time post-transplant prompted by two consecutive drops in the graft BLI signal totaling >30%, and the second ALS dose 48 hours later.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Gated Lymphocytes

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were harvested from the peripheral blood of control and ALS treated mice. Ten drops of tail blood were collected in a BD Vacutainer® tube (BD Falcon) and incubated with 2 ml lysis buffer (BD Pharmigen) for 7 min at room temperature. After centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4°C in polystyrene tube (BD Falcon), PBMCs were washed twice with 1x PBS, resuspended in 2ml PBS, and incubated on ice with 0.5μl FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (BD Pharmigen) and PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a mAbs (BD Pharmigen) for ~1 hr. Cells were washed twice with 1x PBS and re-suspended in 200μl 4% paraformeldayde. The percent gated CD4+ and CD8a+ cells were identified by flow cytometry and calculated from the gated lymphocyte population of PBMCs (CellQuest software package; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections were fixed in acetone and blocked with 0.3% H2O2, 10% normal goat serum, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). The sections were incubated with primary monoclonal antibodies including anti-CD4 (BD Biosciences, H129.19, 1μg/ml), anti-CD8 (BD Biosciences, H3-6.7, 1μg/ml antibodies overnight at 4°C. The sections were then reacted with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibodies. Allografts sections were also stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E).

Data Analysis

The luminescent signals emitted from a given area of the recipient mice were expressed as photons per second. The mean (± SE) signal intensity from each transplant group was calculated and the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical analyses. The time to rejection was expressed as a mean (± SE) for each group and the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical analyses. A probability value of <0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

RESULTS

Islet Graft Imaging and Acute Cellular Rejection

For islet transplants in controls [Group 1, n=12)], Figure 1A shows the mean (±S.E.) BLI signal intensity and non-fasting glucose measurements in diabetic recipients of 200 allogeneic islets transplanted under the renal sub-capsular space. Strong BLI signals (5.07 ± 0.95 × 106 photons/sec) were obtained after transplantation, and the engrafted islet mass efficiently corrected hyperglycemia. In the first two weeks after transplantation, the graft bioluminescent signal intensities fluctuated before stabilizing at the level of approximately 3 × 106 photons/sec, 50 ~60% of the original intensity. The observation that BMI intensity stabilizes after approximately 2 weeks post-transplant has been previously reported (2, 3). Approximately 5 days before permanent recurrence of hyperglycemia, the BLI signal intensity began a progressive decrease. The mean luminescent intensity decreased by approximately 67% to 1.0 ± 0.48 × 106 photons/sec one day before the recurrence of permanent hyperglycemia as a result of allo-rejection. The rejection rate in untreated controls was 92.3% [7.7% rate of spontaneous long-term survival (>100 days)]. The mean (± SE) time to rejection in the control group was 22.5 ± 4.8 days post-transplant.

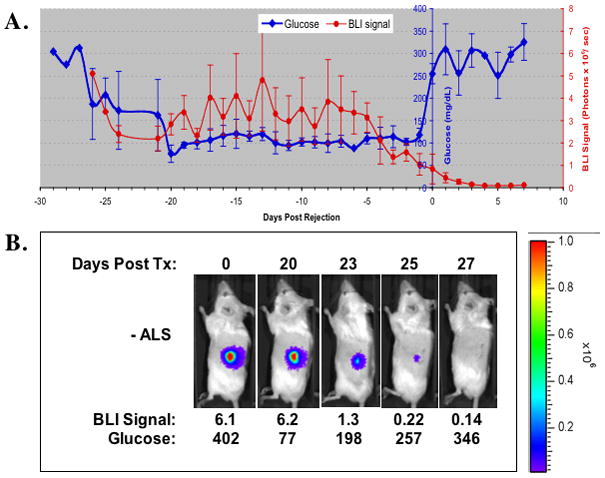

Fig. 1.

(A). Non-fasting blood glucose (blue) and BLI signal measurements (red) after islet transplantation in untreated controls [Group 1 (n=12)]. Diabetic Balb/C mice received transplantation of 200 transgenic RIP-luc islets under the kidney capsule. On the X-axis, “0” represents the day of recurrence of hyperglycemia during rejection. (B). Representative BLI images and corresponding blood glucose measurements according to time post-transplant of a recipient in Group 1.

Figure 1B shows the kinetics of BLI signal intensity post-transplant in a representative animal from Group1. Strong imaging signals were detectable during the period of normoglycemia. On day 23 post- transplant, BLI signal intensity degraded and was associated with elevated blood glucose levels. The BLI signal continued to diminish and eventually disappeared as blood glucose continued to increase above 250 mg/dL as a result of rejection of the islet graft.

ALS Treatment

Islet allograft recipients treated with ALS on transplant days −2 and 0 (Group 2, n=8) resulted in a rejection rate of 88%, and a mean time to rejection of 29.2 ± 9.9 days (p= ns compared to that of group 1 controls). Imaging dynamics were similar to that of the controls (data not shown).

In contrast, islet allogaft recipients that received ALS prompted by a decrease (>30%) in graft BLI signal (Group 3, n=10) had a statistically significantly lower rejection rate, 40%, versus Groups 1 (92.3%, p < 0.05) and 2 (88%, p<0.05). Figure 2A shows the average bioluminescent intensity levels and serum glucose measurements of mice in Group 3 that did not lose complete graft function and remained normoglycemic (n=6). Shortly after islet transplantation, the engrafted islet mass corrected hyperglycemia. The BLI signals stabilized at the level of 3.2 × 106 ± 0.96 photons/sec about two weeks after the transplantation, consistent with previous reports (2,3). Approximately 20 days post-transplant, the BLI intensity began a progressive decline. ALS was administered when the signal intensity decreased by approximately 34% over two consecutive days to 2.1 ± 0.5 × 106 photons/sec. The bioluminescent signal intensity continued to decrease but eventually stabilized at 1.1 ± 0.31 × 106 photons/sec approximately 8 days after ALS treatment. Unlike Groups 1 and 2, hyperglycemia did not occur and the mice remained normoglycemic (glucose <200mg/dl) for over 100 days. Removal of the graft at this point resulted in a prompt recurrence of hyperglycemia (glucose >200mg/dl) indicating dependence on the islet transplant for glycemic control.

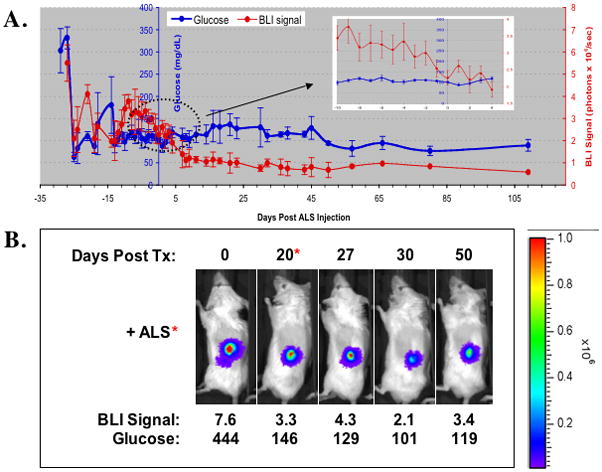

Fig. 2.

(A). Non-fasting blood glucose (blue) and BLI signal measurements (red) after islet transplantation in ALS-treated recipients prompted by changes in BLI [Group 3 (n=10)]. Diabetic Balb/C mice received transplantation of 200 transgenic RIP-luc islets under the kidney capsule. On the X-axis, “0” represents the day of ALS administration. (B). Representative BLI images and corresponding blood glucose measurements according to time post-transplant of an ALS recipient in Group 3 that remained normoglycemic.

Figure 2B shows the changes of bioluminescence imaging in an islet allograft recipient treated with ALS on day 20 prompted by a decline in the BLI signal intensity (from 7.6 × 106 to 3.3 × 106 photons/sec). The ALS treated recipient did not completely lose the graft as indicated by the persistence of BLI signal and by the demonstration of normal glucose control 50 days post-transplant.

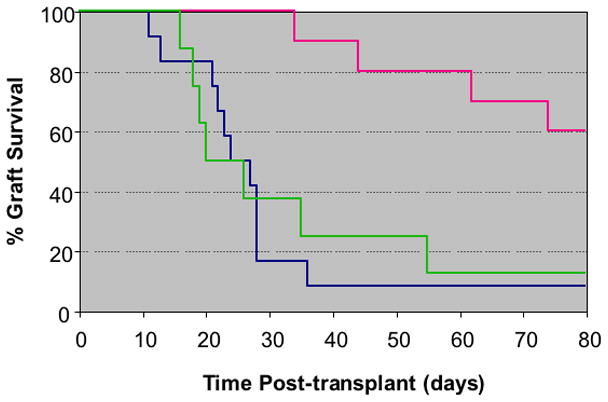

There was a 40% incidence of complete functional graft loss due to rejection in Group 3. The mean time to rejection was 53.5 ± 17.9 days, statistically significantly longer than that of Groups 1 and 2 (p=0.001). Table 1 shows the days to rejection for mice in all three groups. Figure 3 illustrates the percent graft survival for each group calculated by the Kaplan-Meier life-table method.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of islet allograft in untreated controls (Group 1, n=12, BLUE), recipients treated with ALS at the time of transplantation (Group 2, n=8, PINK), and in recipients treated with ALS prompted by a change in BLI (oroup 3, n=12, GREEN).

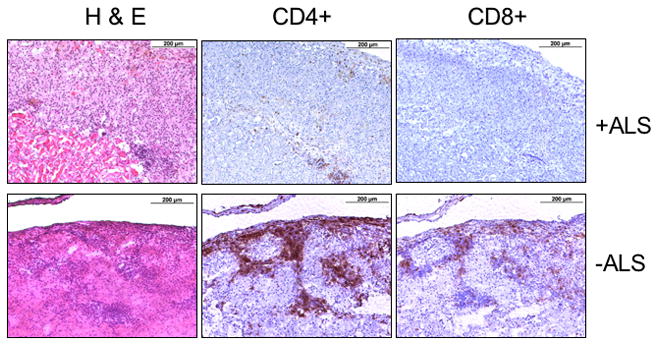

Immunohistology

Figure 4 shows the comparison of representative histologic sections of renal sub-capsular islets from Groups 1 (untreated controls) and 3 (BLI guided ALS treatment) stained for H&E or reacted with anti-CD4, and anti-CD8 antibodies. Graft biopsies were obtained 7 days following BLI signal degradation (for Group 1 biopsies) and the ALS treatment (for Group 3 biopsies). As shown, in the ALS-treated Group 3 grafts, a localized low-degree mononuclear cell infiltration was seen only outside of transplanted islets. Infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were rare in grafts from ALS-treated recipients by day 7 after the treatment. The islet graft maintained intact morphology. In contrast, the graft sections from the non-ALS-treated control group demonstrated a significant amount of infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells with damaged islet graft morphology.

Fig. 4.

Representative graft sections of mice from Groups 1 and 3 stained for H&E or reacted with anti-CD4 or anti -CD8 antibodies. Graft samples were harvested on day 7 after a 30% decline in BLI signal signal intensity in an ALS treated recipient (+ALS, Group 3) or in an untreated control (−ALS, Group 1).

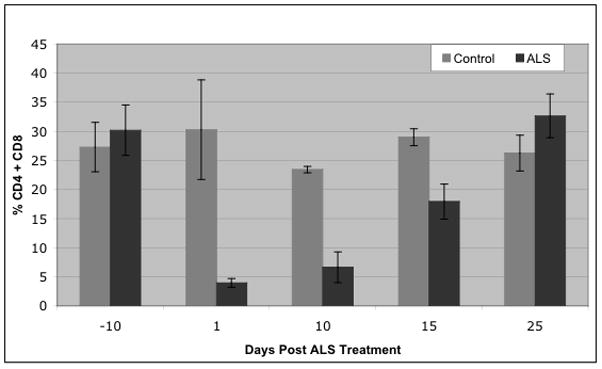

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Gated Lymphocytes

To confirm the effectiveness of ALS in depleting T cells, mice that were administered ALS (0.5 ml ~48 hours apart) were exsanguinated at various time points before and after the treatment. Figure 5 represents the sum of the percent gated CD4+ and CD8a+ cells comparing the ALS treated and non-treated controls. Circulating CD4+ and CD8a+ cells were virtually eliminated approximately 24 hrs following ALS administration and gradually rose to pre-treatment levels within approximately 2–3 weeks.

Fig. 5.

Mean (± S.E.) sum of the percent gated CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral blood lymphocytes in ALS-treated mice and non-treated controls.

DISCUSSION

In vivo real-time imaging in animals is a developing discipline in biomedical research that enables the study of cellular and molecular processes in the context of the living body. BLI has been used in the study of gene-expression in vivo (18), to indicate the extent of tumor growth and response to therapy (19), to assess the extent of protein-protein interactions in vivo (20–22) and to determine the location and proliferation of stem cells (23–25). BLI has also been used to monitor the location and mass (2, 3, 26, 27), and rejection (3, 4) of transplanted cells. These applications of BLI have opened up broad new areas of investigation and provide information that was previously not accessible to investigators.

We have previously reported that BLI can detect early rejection of transplanted allogeneic islets prior to the recurrence of hyperglycemia in a functional mouse model of islet transplantation (3). In this report, we showed that application of BLI could also be used in conjunction with anti-rejection treatment to delay or to prevent complete rejection of islet allografts in histoincompatible donor-recipient combinations. Balb/C mice treated with ALS prompted by a significant decrease in donor graft BLI signal resulted in prolonged graft survival and a significantly lower rate of rejection than that of non-ALS treated recipients, or recipients pre-treated with ALS prior to islet transplantation. The results of the later group is consistent with the hypothesis that the proximity of ALS treatment to the onset of a rejection process is a critical factor necessary to minimize rejection rates, or prolong the time to graft loss from rejection. Merely giving ALS, even at the time of transplantation, will not result in any meaningful decrease in rejection rates, but could slightly prolong the day until rejection occurs.

ALS is a potent immunosuppressive drug widely used in experimental transplantation and in clinical solid organ transplantation (28). The immunosuppressive property of ALS is primarily mediated through depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, although ALS may possibly exert an immunomodulatory effect by promoting partial T cell anergy via ligation of multiple surface receptors (29). ALS depletes approximately 80% of the monocytes and natural killer cells and may also diminish the numbers of dendritic cells (7). The mechanism involved in the long-term acceptance of islet allografts induced by ALS has been reported to be due to ALS-inducing host hyporesponsiveness, not tolerance, since transplantation of donor skin or infusion of donor spleen cells cause acute rejection of long-term-accepted islet allografts (11). It is possible that the ALS-induced T cell depletion resulted in homeostatic proliferation of residual T cells and their conversion into alloantigen-reactive memory-like T cells, potentially posing a barrier to the establishment of transplantation tolerance (30). In addition to the T cell-depleting effect, CD4+ regulatory T cells are reported to be spared from deletion by ALS (30). The concomitant presence of T cell deletion and continuous regulatory T cell activity may underlie the therapeutic effect of ALS in transplant immune suppression. The precise mechanism(s) underlying prolonged allograft survival in the BLI prompted ALS treated animals was considered outside the scope of this report, and would require further study.

We did not observe a statistically significant difference in the mean time to rejection between that of non-ALS treated controls and that of ALS-pre-treated mice. This finding was consistent with previous reports that ALS treatment administered prior to transplantation had no significant effect in prolonging the mean survival time of the allogeneic islet grafts (17, 31). However, this may be affected by the donor/recipient strains used and the site of transplantation since the rapidity of the rejection response can be different among different strain combinations and according to implantation site. In our studies, the mean day of rejection in untreated controls that received islets under the kidney capsule was 22.5 days, a time course in which re-population of lymphocytes would occur in the ALS treated animals, It was interesting to observe that most of the recipients (6/10) that were treated with ALS during the rejection reaction subsequently had long-term survival of >100 days. Although the mechanisms are not clear, the presence of alloantigen stimulated lymphocytes at the time of ALS treatment may be necessary for ALS to exert its effect on longer-term host hyporesponsiveness.

The primary objective of the study was to determine whether an imaging modality such as BLI can be used to detect early graft rejection to guide the timing of anti-rejection treatment, and whether it will prolong islet graft survival. This study demonstrated that the timing of anti-rejection treatment with a T-cell depleting agent such as ALS will protect islet allograft survival and function. The findings underscore the importance of early detection of rejection by methods, such as in vivo imaging, that precede the change in glycemic control to prompt the timing of anti-rejection treatment. These results demonstrated that non-invasive imaging modalities such as BLI can detect and prompt the timing of treatment of islet allograft rejection, and that ALS treatment of acute cellular rejection can protect the grafts from permanent loss. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the application of BLI in guiding the timing of anti-rejection treatment to achieve significant prolongation of islet graft survival. These observations demonstrate the utility of using a sensitive, real-time, imaging modality to detect changes in islet mass due to immune-mediated injury to guide timing of immunotherapy.

Table I.

Mean time (days) to rejection and proportion of rejection of allogeneic islet grafts according to use of BLI to prompt anti-lymphocyte serum treatment.

| Group (n) | Days to Rejection | Mean (± S.E.) | % Rejection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n=12) Control – No ALS |

11, 13, 21, 21, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 36, >100 | 22.5 ± 4.8 | 92% |

| Group 2 (n=8) ALS Pre-Tx (no BLI) |

16, 18, 19, 20, 26, 35, 55, >100 | 27.0 ± 9.85 | 88% |

| Group 3 (n=10) ALS @ BLI Prompt |

34, 44, 62, 74, >100 (6) | 53.5 ± 17.9*. ** | 40% |

p=0.01, vs group 1;

p=0.01, vs Group 2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK063565 (D. B. K.).

The authors acknowledge Jie He for excellent technical expertise.

References

- 1.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation [see comment] New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355 (13):1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Kaufman DB. Bioluminescence Imaging of Pancreatic Islet Transplants. Curr Med Chem. 2004;4:301. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Zhang X, Larson CS, Baker MS, Kaufman DB. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of transplanted islets and early detection of graft rejection. Transplantation. 2006;81 (10):1421. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000206109.71181.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka M, Swijnenburg RJ, Gunawan F, et al. In vivo visualization of cardiac allograft rejection and trafficking passenger leukocytes using bioluminescence imaging. Circulation. 2005;112 (9 Suppl):I105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnefoy-Berard N, Vincent C, Revillard JP. Antibodies against functional leukocyte surface molecules in polyclonal antilymphocyte and antithymocyte globulins. Transplantation. 1991;51 (3):669. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199103000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rebellato LM, Gross U, Verbanac KM, Thomas JM. A comprehensive definition of the major antibody specificities in polyclonal rabbit antithymocyte globulin. Transplantation. 1994;57 (5):685. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199403150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geissler I, Sawyer GJ, Dong X, Kandil H, Davies ET, Fabre JW. The effect of anti-lymphocyte serum on subpopulations of blood and tissue leucocytes: possible supplementary mechanisms for suppression of rejection and the development of opportunistic infections. Transplant International. 2005;18 (12):1366. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hale DA, Gottschalk R, Maki T, Monaco AP. Determination of an improved sirolimus (rapamycin)-based regimen for induction of allograft tolerance in mice treated with antilymphocyte serum and donor-specific bone marrow. Transplantation. 1998;65 (4):473. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufman DB, Shapiro R, Lucey MR, Cherikh WS, RTB, Dyke DB. Immunosuppression: practice and trends. American Journal of Transplantation. 2004;4 (Suppl 9):38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6135.2004.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray BN, Watkins E., Jr Isolated islet transplantation in experimental diabetes. Australian Journal of Experimental Biology & Medical Science. 1976;54 (1):57. doi: 10.1038/icb.1976.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh M, Porter J, Monaco AP, Maki T. Induction of antigen-specific unresponsiveness to pancreatic islet allografts by antilymphocyte serum. Transplantation. 1988;45 (2):429. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198802000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aebischer P, Lacy PE, Gerasimidi-Vazeou A, Hauptfeld V. Production of marked prolongation of islet xenograft survival (rat to mouse) by local release of mouse and rat antilymphocyte sera at transplant site. Diabetes. 1991;40 (4):482. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maki T, Ichikawa T, Blanco R, Porter J. Long-term abrogation of autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by immunotherapy with anti-lymphocyte serum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89 (8):3434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markees TG, De Fazio SR, Gozzo JJ. Prolongation of impure murine islet allografts with antilymphocyte serum and donor-specific bone marrow. Transplantation. 1992;53 (3):521. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Inverardi L, Molano RD, Pileggi A, Ricordi C. Nonlethal conditioning for the induction of allogeneic chimerism and tolerance to islet allografts. Transplantation. 2003;75 (7):966. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000058516.74246.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufour JM, Rajotte RV, Kin T, Korbutt GS. Immunoprotection of rat islet xenografts by cotransplantation with sertoli cells and a single injection of antilymphocyte serum. Transplantation. 2003;75 (9):1594. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000058748.00707.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Q, Wang D, Hadley GA, Bingaman AW, Bartlett ST, Farber DL. Long-term islet graft survival in NOD mice by abrogation of recurrent autoimmunity. Diabetes. 2004;53 (9):2338. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contag CH, Spilman SD, Contag PR, et al. Visualizing gene expression in living mammals using a bioluminescent reporter. Photochemistry & Photobiology. 1997;66 (4):523. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney TJ, Mailander V, Tucker AA, et al. Visualizing the kinetics of tumor-cell clearance in living animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96 (21):12044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massoud TF, Paulmurugan R, De A, Ray P, Gambhir SS. Reporter gene imaging of protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2007;18 (1):31. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massoud TF, Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of homodimeric protein-protein interactions in living subjects. FASEB Journal. 2004;18 (10):1105. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1128fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulmurugan R, Massoud TF, Huang J, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of drug-modulated protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Cancer Research. 2004;64 (6):2113. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao YA, Wagers AJ, Beilhack A, et al. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101 (1):221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, et al. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113 (7):1005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan M, Park JM, Cao F, et al. Effects of epigenetic modulation on reporter gene expression: implications for stem cell imaging. FASEB Journal. 2006;20 (1):106. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4551fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y, Dang H, Middleton B, et al. Bioluminescent Monitoring of Islet Graft Survival after Transplantation. Molecular Therapy: the Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2004;9 (3):428. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler M, Virostko J, Chen Z, et al. Assessment of pancreatic islet mass after islet transplantatiion using in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Transplantation. 2005;79 (7):768. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000152798.03204.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helderman JH, Bennett WM, Cibrik DM, Kaufman DB, Klein A, Takemoto SK. Immunosuppression: practice and trends. American Journal of Transplantation. 2003;3 (Suppl 4):41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.3.s4.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merion RM, Howell T, Bromberg JS. Partial T-cell activation and anergy induction by polyclonal antithymocyte globulin. Transplantation. 1998;65 (11):1481. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199806150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minamimura K, Gao W, Maki T. CD4+ regulatory T cells are spared from deletion by antilymphocyte serum, a polyclonal anti-T cell antibody. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176 (7):4125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali A, Garrovillo M, Jin MX, Hardy MA, Oluwole SF. Major histocompatibility complex class I peptide-pulsed host dendritic cells induce antigen-specific acquired thymic tolerance to islet cells. Transplantation. 2000;69 (2):221. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]