Abstract

Enhanced glutamatergic neurotransmission in dopamine (DA) neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA), triggered by a single cocaine injection, represents an early adaptation linked to the more enduring effects of abused drugs that characterize addiction. Here, we examined the impact of in vivo cocaine exposure on metabotropic inhibitory signaling involving G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (Girk) channels in VTA DA neurons. Somatodendritic Girk currents evoked by the GABAB receptor (GABABR) agonist baclofen were diminished in a dose-dependent manner in mice given a single cocaine injection. This adaptation persisted for 3–4 d, was specific for DA neurons of the VTA, and occurred in parallel with an increase in spontaneous glutamatergic neurotransmission. No additional suppression of GABABR–Girk signaling was observed following repeated cocaine administration. While total Girk2 and GABABR1 mRNA and protein levels were unaltered by cocaine exposure in VTA DA neurons, the cocaine-induced decrease in GABABR–Girk signaling correlated with a reduction in Girk2-containing channels at the plasma membrane in VTA DA neurons. Systemic pretreatment with sulpiride, but not SCH23390 (7-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrahydro-3-benzazepin-8-ol), prevented the cocaine-induced suppression of GABABR–Girk signaling, implicating D2/3 DA receptor activation in this adaptation. The acute cocaine-induced weakening of somatodendritic Girk signaling complements the previously demonstrated cocaine-induced strengthening of glutamatergic neurotransmission, likely contributing to enhanced output of VTA DA neurons during the early stages of addiction.

Introduction

The mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) system consists of projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra (SN) to cortical and limbic structures such as the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens (Björklund and Dunnett, 2007). VTA DA neurons mediate responses to rewards and reward-predicting stimuli, thus representing a key component of the reward learning circuitry (Kelley, 2004; Hyman et al., 2006). VTA DA neuron output is dependent on glutamatergic input from cortical and subcortical brain regions (Carr and Sesack, 2000; Omelchenko and Sesack, 2005). Glutamatergic neurotransmission in VTA DA neurons is strengthened following a single cocaine exposure (Ungless et al., 2001) and is critical for the development of behavioral sensitization (Robinson and Berridge, 2001; Kauer and Malenka, 2007).

VTA DA neuron output is also sensitive to negative autocrine and paracrine (“long-loop”) feedback mediated by D2 DA receptors (D2Rs) and GABAB receptors (GABABRs), respectively (Einhorn et al., 1988; Sugita et al., 1992). While repeated cocaine dosing has been shown to temper D2R- and GABABR-dependent signaling in VTA DA neurons (Ackerman and White, 1990; Kushner and Unterwald, 2001), acute effects of cocaine on these inhibitory pathways have not been reported. Postsynaptic inhibitory effects of GABABR and D2R activation are mediated primarily by activation of G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (Girk/KIR3) channels (Beckstead et al., 2004; Cruz et al., 2004; Labouèbe et al., 2007; Arora et al., 2010). Recent work has shown that the strength of Girk signaling pathways can be modulated by diverse stimuli, including neuronal activity and opioids (Chung et al., 2009; Nassirpour et al., 2010). Here, we examined whether the strength of Girk-dependent signaling in VTA DA neurons is affected by acute and repeated cocaine exposure.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Animal use was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota. Adult male and female C57BL/6J (The Jackson Laboratory) were used to establish breeding cages; offspring were used for all studies. Mice were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle, with food and water available ad libitum.

Drugs.

Baclofen, quinpirole, cocaine hydrochloride, 7-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrahydro-3-benzazepin-8-ol (SCH23390), and sulpiride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [S-(R*,R*)]-[3-[[1-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino]-2-hydroxypropyl](cyclohexylmethyl)phosphinic acid (CGP54626) was purchased from Tocris.

Locomotor activity.

Locomotor activity studies were performed as described previously (Pravetoni and Wickman, 2008). For acute cocaine studies, mice (4–5 weeks) were acclimated over a 4 d period to handling and open-field chambers (1 h/d), receiving saline injections on days 3 (s1) and 4 (s2). On day 5, animals were given saline or cocaine (3, 15, 30 mg/kg, i.p.). Some subjects were pretreated with saline, SCH23390 (0.18 mg/kg, i.p.), or sulpiride (50 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min before the injection of saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.). For repeated cocaine experiments, mice were acclimated over a 2 d period, followed by five consecutive daily injections of saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.). In all instances, total distance traveled was measured over the 1 h postinjection interval.

Electrophysiology.

Coronal slices containing the VTA (200–225 μm) were prepared from saline- and cocaine-treated wild-type mice (4–6 weeks) 1–2, 3–5, or 10–12 d after the final injection. All procedures related to slice preparation and measurement of GABABR/baclofen- or D2R/quinpirole-induced responses in VTA DA neurons were recently described in detail (Arora et al., 2010). Spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) were measured over a 2–3 min period at a holding potential of −80 mV, in the presence of picrotoxin (100 μm), in a subset of tested neurons. Kynurenic acid (2 mm) was applied to verify that observed events were mediated by ionotropic glutamate receptors. To determine the sensitivity of GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons, peak outward currents were measured following the successive application of 2, 20, and 200 μm baclofen to the same cell. EC50 values for baclofen activation of outward currents in VTA DA neurons from saline- and cocaine-treated mice were extracted from curves (least-squares) fitting mean peak currents evoked by each baclofen concentration in VTA DA neurons from saline- (n = 8) and cocaine-treated (n = 7) mice.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Brains were extracted from mice (6–8 weeks) 24 h after saline or cocaine injection (30 mg/kg, i.p.), and placed in ice-cold PBS; 600 μm coronal sections were cut by vibratome. A blunt 16 gauge needle was used to core out tissue containing the VTA. Punches were frozen on crushed dry ice and stored at −80°C. Poly(A)+ mRNA was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (QIAGEN) and diluted in water to a final volume of 100 μl. Real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green Brilliant II qRT-PCR kit and an MX3005P thermal cycler, following manufacturer's specifications (Agilent Technologies). qRT-PCR conditions, including oligonucleotide sequences, are available on request. GAPDH mRNA levels in each sample were used for normalization purposes using GAPDH QuantiTect oligonucleotides (QIAGEN). Samples were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Immunohistochemistry.

Twenty-four hours after injection of saline or cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.), male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks) were subjected to transcardial perfusion with Ca2+-free Tyrode's solution, followed by a 4% paraformaldehyde-based fixative. Brains were placed into a 10% sucrose solution and flash-frozen onto chucks for sectioning. Tissue from cocaine- and saline-treated mice (n = 6/group) was embedded on separate blocks, frozen, cut in 10 μm sections (coronal), and affixed to ProbeOn Plus microslides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sections were boiled in 10 mm citric acid, pH 6.0, incubated in 0.2% Triton X-100/0.2% Tween 20/TBS, and incubated overnight at room temperature with antibodies directed against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (1:1000; Pierce) in addition to either Girk2 (1:5000; Alomone Labs) or GABABR1 (1:500). Antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 0.2% casein (USB) and 0.2% Tween 20. Sections were washed with TBS (three times, 20 min each) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 1:500 dilutions of Cy3-conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit and Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-sheep secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were washed with TBS (three times, 20 min each), dehydrated, cleared with xylenes, and coverslipped using DPX (Fluka).

Digital images were prepared for publication with Photoshop software (Adobe). Images were collected using a conventional fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX-50; Olympus) and a 40× objective. TH immunoreactivity was used to identify VTA DA neurons and was thresholded automatically; the thresholded area was used to define the regions of interest. Mean pixel intensity of GABABR1 or Girk2 labeling within those regions was measured on a scale from 0 to 255 using ImageJ.

Immunoelectron microscopy.

Plasma membrane and intracellular levels of GABABR1 and Girk2 in TH-positive dendrites of the VTA were measured 24 h following acute cocaine or saline injection using preembedding immunoelectron microscopy and quantitative analysis approach described previously (Koyrakh et al., 2005; Arora et al., 2010). Primary antibodies included the following: monoclonal antibody anti-TH (Calbiochem), rabbit polyclonal anti-GABABR1 (B17), and guinea-pig polyclonal anti-Girk2 (Aguado et al., 2008). TH immunoreactivity was visualized by the immunoperoxidase reaction, while Girk2 or GABABR1 immunoreactivity was visualized by the silver-intensified immunogold reaction. Secondary antibody mixtures included the following: goat anti-rabbit (Fab fragment; diluted 1:100) coupled to 1.4 nm gold (Nanoprobes), goat anti-guinea pig (Fab fragment; diluted 1:100) coupled to 1.4 nm gold (Nanoprobes), and biotinylated goat anti-mouse (diluted 1:100; Vector Laboratories). All antibodies were diluted in 1% NGS/TBS.

To test the method specificity of the electron microscopy procedures, the primary antibody was omitted or replaced with 5% (v/v) normal serum of the species of the primary antibody. Under these conditions, no selective labeling was observed. In addition, some sections were incubated with both gold-labeled and biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by the ABC complex and peroxidase reaction without silver intensification. This resulted in amorphous horseradish peroxisade (HRP) end product, and no metal particles were detected. Using the same sequence but with silver intensification and without the HRP reaction, resulted in silver grains but no amorphous HRP end product. Under these conditions, only infrequent small patches of HRP end product were detected, and the patches were not associated selectively with any particular cellular profile. In addition, the selective location of the signals in structures labeled with only one or the other of the signaling products within the same section, as well as having side-by-side double-labeled structures, showed that the procedures did not produce false-positive double-labeling results.

For each experimental group, a total of nine tissue blocks were obtained (three animals per group and three samples per animal). Electron-microscopic ultrathin sections were cut close to the surface of each block because immunoreactivity decreased with depth. Randomly selected areas were captured at a final magnification of 50,000×, and measurements covered a total section area of 6000 μm2. TH-positive dendritic shafts were assessed for the presence of immunoparticles for Girk2 or GABABR1. In total, 75 dendrites were selected, and the area of individual dendritic profiles was measured. The density of Girk2 or GABABR1 on the plasma membrane of TH-positive neurons was measured as the number of immunoparticles per square micrometer.

Data analysis.

Data are presented throughout as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) and SigmaPlot (Systat Software). sEPSCs were analyzed using Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft). No gender differences in motor activity, or any electrophysiological parameter, were observed. As such, data from male and female mice were pooled to increase the power of the studies. Group comparisons of motor activity data were performed with one-way, two-way, and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Immunoelectron microscopy data was analyzed using a Mann–Whitney rank sum test, while electrophysiological data were analyzed with Student's t test, one-way, or two-way ANOVA. Tukey's multiple-comparison and Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc tests were used for pairwise comparisons when significant group-dependent differences were observed.

Results

To evaluate the effects of acute cocaine exposure on GABABR–Girk signaling, baclofen-induced somatodendritic currents were measured in VTA DA neurons in acutely isolated slices from C57BL/6 mice (4–6 weeks), 1–12 d following a single cocaine injection (3, 15, 30 mg/kg, i.p.). Cells exhibiting relatively large capacitances (>50 pF), Ih currents (>100 pA at −120 mV), moderate and stable spontaneous activities (1–5 Hz), and relatively long action potential durations (APDs) (APD > 2.5 ms) were targeted, as this collective profile correlates well with expression of the DA neuron-specific markers tyrosine hydroxylase and Pitx3 (Grace and Onn, 1989; Johnson and North, 1992; Neuhoff et al., 2002; Mathon et al., 2005; Labouèbe et al., 2007).

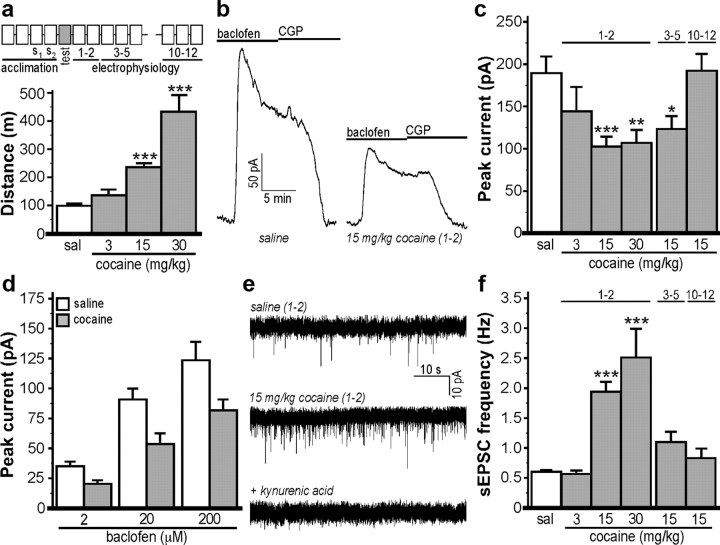

Acute cocaine induced a dose-dependent increase in locomotor activity (Fig. 1a). As shown previously (Cruz et al., 2004; Arora et al., 2010), the GABABR agonist baclofen evoked robust outward Girk-dependent currents in VTA DA neurons from saline-treated mice that correlated with a decrease in input resistance (data not shown) and showed a characteristic acute desensitization (Fig. 1b). Baclofen-evoked currents were significantly reduced in cocaine-treated mice for up 3–5 d, but not 10–12 d following cocaine exposure, with maximal suppression seen at 1–2 d and 15 mg/kg cocaine (Fig. 1c). The reduction in baclofen-induced currents seen in VTA DA neurons from cocaine-treated mice did not correlate with differences in key electrophysiological properties of the VTA DA neurons in question, including apparent capacitance, input resistance, Ih current amplitude, spontaneous firing rate, or action potential duration (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cocaine suppresses inhibitory signaling in VTA DA neurons. a, Total distance traveled on test day by C57BL/6J mice (7–25 per group) following administration of saline (sal) or cocaine (3, 15, 30 mg/kg; F(3,54) = 21.8; p < 0.001); activity was monitored for 1 h after injection. The diagram above the plot depicts the schedule of subject handling, which included 4 acclimation days, a test day, and three distinct time frames (1–2, 3–5, 10–12 d after injection) within which all electrophysiological assessments were made. b, Representative somatodendritic currents (Vhold = −60 mV) evoked by a saturating concentration of baclofen (200 μm) in VTA DA neurons from mice treated on test day with saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg). The lines above the traces denote the duration of drug application. Baclofen-induced currents were reversed by the GABABR antagonist CGP54626 (2 μm; CGP). c, Mean baclofen-induced currents in VTA DA neurons from saline- and cocaine-treated mice (n = 5–24 per group). The x-axis labels refer to the type of test day injection. The labels above the bars denote the time frame (in days after injection) of the recordings. Significant effects of cocaine dose (F(3,57) = 7.2; p < 0.001), in addition to recording time frame (1–2, 3–5, 10–12 d) on baclofen-induced currents were observed among animals treated with 15 mg/kg cocaine (F(3,59) = 8.0; p < 0.001). d, Mean peak currents (in picoamperes) triggered by increasing concentrations of baclofen (2, 20, 200 μm) applied to the same cell in slices from mice treated with either saline or 30 mg/kg cocaine (1–2 d after injection). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of drug (F(1,45) = 15.1; p < 0.001) and baclofen concentration (F(2,45) = 33.7; p < 0.001), but no drug by baclofen concentration interaction (F(2,45) = 1.4; p = 0.3), consistent with the lack of impact of cocaine treatment on the sensitivity of GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons. Maximum current amplitudes were slightly smaller than those measured in cells receiving a single saturating baclofen exposure, likely attributable to desensitization triggered by successive baclofen applications. e, Representative sEPSCs measured in VTA DA neurons 1–2 d after the injection of saline or cocaine. sEPSCs in control and cocaine-treated mice were blocked by kynurenic acid (2 mm). f, Mean sEPSC frequency (F(4,61) = 15.5; p < 0.001) across the six groups (n = 4–23 per group). Data from saline-treated subjects were pooled as recording time frame did not affect currents, sEPSC amplitudes, or sEPSC frequencies. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, and ***p < 0.001, respectively, versus sal. Error bars indicate SEM.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological summary data for VTA DA neurons

| Group | Group sizes |

CM (pF) | RM (MΩ) | Ih (pA) | Spontaneous activity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | Incidence | Rate (Hz) | APD (ms) | ||||

| Saline | 13 | 22 | 100 ± 3 | 510 ± 44 | 245 ± 30 | 19 of 22 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| Cocaine | ||||||||

| 3 mg/kg (1–2) | 2 | 5 | 99 ± 10 | 696 ± 144 | 293 ± 69 | 4 of 5 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

| 15 mg/kg (1–2) | 11 | 24 | 95 ± 5 | 875 ± 193 | 208 ± 23 | 21 of 24 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| 15 mg/kg (3–5) | 4 | 10 | 100 ± 6 | 419 ± 55 | 277 ± 46 | 8 of 10 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| 15 mg/kg (10–12) | 3 | 8 | 108 ± 6 | 485 ± 82 | 349 ± 38 | 7 of 8 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| 30 mg/kg (1–2) | 4 | 10 | 94 ± 7 | 413 ± 54 | 301 ± 61 | 4 of 10 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

Summary electrophysiological properties of VTA DA neurons measured as part of the study depicted in Figure 1C. The time frame (in days after injection) during which electrophysiological recordings were made in VTA DA neurons from cocaine-treated mice is noted in parentheses next to the cocaine dose that was administered. Data were compiled from a total of N different mice per group and n total cells. Cocaine treatment had no significant impact on cell capacitance (CM: F(5,63) = 0.71, p = 0.62), input/membrane resistance (RM: F(5,71) = 1.85, p = 0.11), Ih current amplitude (Ih: F(5,69) = 1.66, p = 0.16), rate of spontaneous activity (rate: F(5,57) = 2.22, p = 0.07), or action potential duration (APD: F(5,57) = 0.83, p = 0.54).

Following reversal of the baclofen-induced current by the GABABR antagonist CGP54626, some VTA DA neurons were challenged with a saturating concentration (10 μm) of the D2R receptor agonist quinpirole, which also activates Girk channels in midbrain DA neurons (Beckstead et al., 2004). Quinpirole-induced currents measured in VTA DA neurons were not strongly influenced by prior baclofen exposure, but were consistently and substantially smaller than baclofen-induced responses measured in the same neurons (data not shown). More importantly, quinpirole-induced currents measured in VTA DA neurons from cocaine-treated mice (15 mg/kg, 1–2 d after injection) were significantly smaller (20 ± 3 pA; n = 20; t(37) = 3.2; p < 0.01) than quinpirole-induced currents in VTA DA neurons from saline-treated controls (47 ± 8 pA; n = 19). Thus, somatodendritic Girk channel currents linked to two distinct G-protein-coupled receptors in VTA DA neurons were suppressed by acute cocaine exposure.

The sensitivity of Girk channels in VTA DA neurons to GABABR activation is dependent on the RGS family member RGS2, expression of which can be influenced by exposure to drugs of abuse (Labouèbe et al., 2007). Thus, we next examined the impact of acute cocaine exposure on the sensitivity of GABABR–Girk signaling by applying increasing concentrations of baclofen (2, 20, 200 μm) to cells 1–2 d following saline or cocaine treatment. While VTA DA neurons from cocaine-treated mice displayed a reduction in peak current amplitude at each concentration tested (Fig. 1d), the mean EC50 values for baclofen activation of Girk current in VTA DA neurons from saline- (12 ± 2 μm) and cocaine-treated (15 ± 2 μm) mice were not significantly different (p = 0.7). Thus, acute cocaine does not alter the sensitivity of GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons. Furthermore, currents evoked by a single saturating dose (saline, 159 ± 38 pA; cocaine, 227 ± 51 pA; n = 5–6 per group, t(9) = 1.0, p = 0.3) of baclofen in DA neurons from the SN pars compacta were not reduced by cocaine exposure (data not shown), suggesting that the cocaine-induced adaptation in GABABR–Girk signaling is selective for DA neurons of the VTA.

Previous studies have shown that acute cocaine enhances AMPA-dependent glutamatergic signaling (Ungless et al., 2001; Argilli et al., 2008). Consistent with these findings, we observed that a single cocaine exposure induced a dose-dependent increase in the frequency of spontaneous glutamatergic EPSCs (sEPSCs) in VTA DA neurons measured 1–2 d after injection compared with saline-treated controls (Fig. 1e,f). Only a modest impact (∼10%) of cocaine on sEPSC amplitude was observed, and only at the highest cocaine dose tested (30 mg/kg) (data not shown). No significant differences between saline and cocaine treatment groups were observed with respect to sEPSC frequency or amplitude at 3–5 or 10–12 d following injection. Thus, acute cocaine exposure triggers transient adaptations in both Girk and glutamatergic signaling in VTA DA neurons.

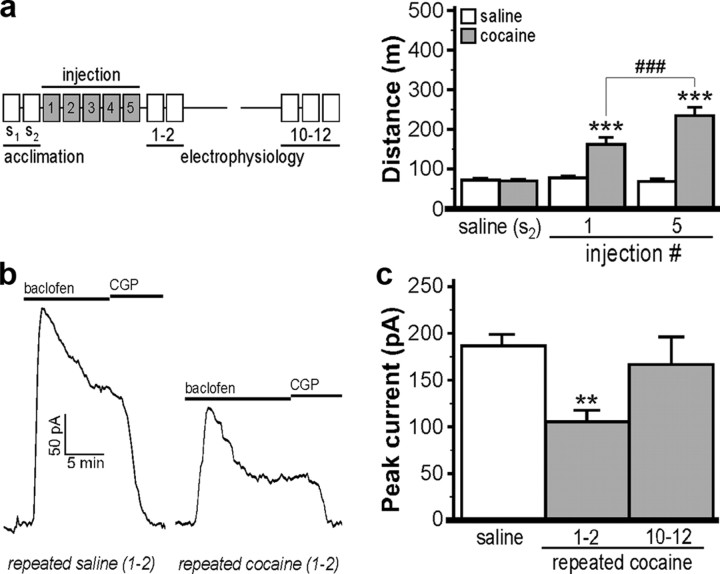

To determine whether repeated cocaine administration potentiates the magnitude or duration of the decreased GABABR–Girk signaling triggered by acute cocaine, VTA slices were prepared from mice receiving five daily injections of cocaine (15 mg/kg) or saline 1–2 or 10–12 d following the final injection. Cocaine-treated mice displayed enhanced locomotor activity on the fifth compared with the first injection day, indicative of behavioral sensitization (Fig. 2a). Mice receiving multiple injections of cocaine exhibited a decrease in baclofen-induced currents at 1–2 d but not 10–12 d after the final injection as compared with saline controls (Fig. 2b,c). The magnitude of this decrease in GABABR–Girk signaling triggered by repeated cocaine, however, was comparable with that elicited by a single cocaine exposure.

Figure 2.

Repeated cocaine dosing decreases GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons. a, Total distance traveled by mice (n = 5–17 per group) at three stages of a repeated cocaine dosing regimen, depicted left of the plot. Subjects were randomly assigned to saline (white) or cocaine (15 mg/kg; gray) groups; activity was assessed after injection of saline (s2 acclimation day) and after the first and fifth cocaine injection days. Two-way ANOVA revealed a drug by day interaction (F(2,56) = 26.1; p < 0.001). Only within-drug comparisons are displayed on the plot. ***p < 0.001 versus saline (s2) activity; ###p < 0.001. b, Representative currents evoked by 200 μm baclofen in VTA DA neurons from mice given repeated saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg) injections; recordings were made 1–2 d following the last injection. c, Mean baclofen-induced peak currents measured 1–2 and 10–12 d following the last injection of saline or cocaine (n = 6–14 per group; F(2,25) = 5.4; p < 0.05). Data from saline-treated subjects were pooled as recording time frame did not affect baclofen-induced currents. **p < 0.01 versus saline group. Error bars indicate SEM.

The cocaine-induced decrease in GABABR–Girk signaling could be explained by a downregulation of one or more elements of the GABABR–Girk signaling pathway in VTA DA neurons. Therefore, we used quantitative RT-PCR to measure the impact of acute cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.) on the levels of GABABR1, Girk2, and Rgs2 mRNAs in VTA-enriched micropunches. No significant difference was observed between saline- and cocaine-treated mice in the level of GABABR1 [mean Ct value (CV); saline, 6.9 ± 0.3, vs cocaine, 6.8 ± 0.2; n = 4/group; t(6) = 0.29, p = 0.8], Girk2 (CV; saline, 11.8 ± 0.4, vs cocaine, 11.7 ± 0.3; n = 4/group; t(6) = 0.14, p = 0.9), or Rgs2 (CV; saline, 7.7 ± 0.2, vs cocaine, 7.8 ± 0.2; n = 3/group; t(4) = −0.47, p = 0.7) mRNA in the VTA.

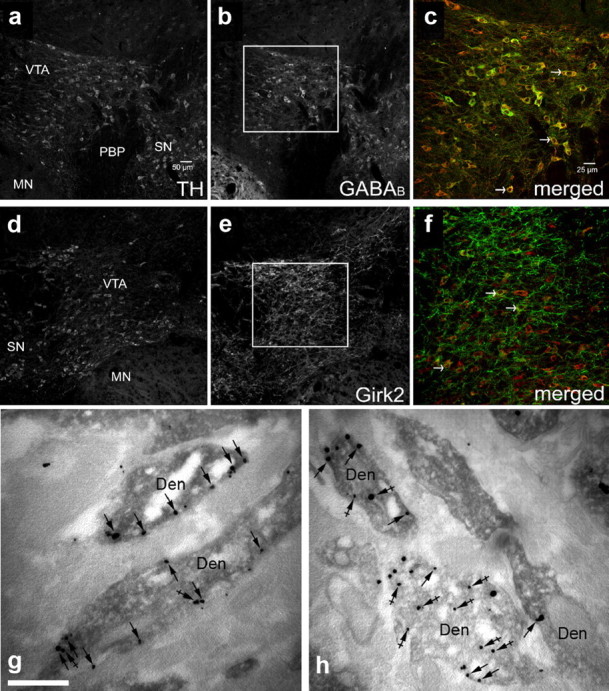

Given the cell type specificity of the cocaine-induced adaptation, and the heterogeneity of cell types in the VTA, quantitative immunohistochemistry and immunoelectron microscopy approaches were used to measure the impact of acute cocaine on GABABR1 (Fig. 3a–c) and Girk2 (Fig. 3d–f) protein in TH-positive regions of the VTA. No significant difference was detected between saline- and cocaine-treated mice in the levels of total GABABR1 (saline, 72.5 ± 6.1, vs cocaine, 82.6 ± 4.2 pixels; t(9) = −1.4, p = 0.2) or Girk2 (saline, 78.6 ± 9.5, vs cocaine, 67.2 ± 4.8 pixels; t(6) = 1.1, p = 0.3) proteins in TH-positive regions of the VTA (n = 5–6 per group). We did, however, detect a significant cocaine-induced decrease in the density of Girk2 (Fig. 3g,h; median immunoparticles/μm2; saline, 1.9, vs cocaine, 0.7; n = 49–54; U = 593, p < 0.001) but not GABABR1 (data not shown) (median immunoparticles/μm2; saline, 1.1, vs cocaine, 1.1; n = 52–54; U = 1376, p = 0.9) proteins in the plasma membrane of TH+ dendrites of the VTA. Thus, the acute cocaine-induced suppression of somatodendritic Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons is mirrored by a reduction in Girk2-containing channels in dendritic membranes.

Figure 3.

Acute cocaine decreases the density of Girk2 on the plasma membrane of VTA DA neurons. a–f, Representative images of GABABR1 and Girk2 immunoreactivity in TH-positive VTA neurons. Immunoreactivity for TH (a, d), GABABR1 (b), and Girk2 (e) in VTA-containing sections from a saline-treated mice. c, f, High-magnification views of the regions outlined in b and e, showing immunoreactivity for TH in red and either GABABR1 (c) or Girk2 (f) in green. The arrowheads show some examples of neurons exhibiting clear somatic labeling for TH and either GABABR1 or Girk2. Abbreviations: MN, Mammillary nuclei; PBP, parabrachial pigmented nucleus; SN, substantia nigra. Immunoreactivity for Girk2 in VTA DA neurons from saline- (g) or cocaine-treated (h) dopaminergic neurons of the VTA, as detected using preembedding dual-labeling immunoelectron microscopy. In control conditions, the peroxidase reaction product (TH immunoreactivity) filled dendritic shafts (Den), whereas immunoparticles (Girk2 immunoreactivity) were located along the extrasynaptic plasma membrane (arrows) and at intracellular sites (crossed arrows). A reduction in Girk2 immunoreactivity along the plasma membrane (arrows) was evident 24 h following an acute injection of 30 mg/kg cocaine. Scale bar, 0.5 μm.

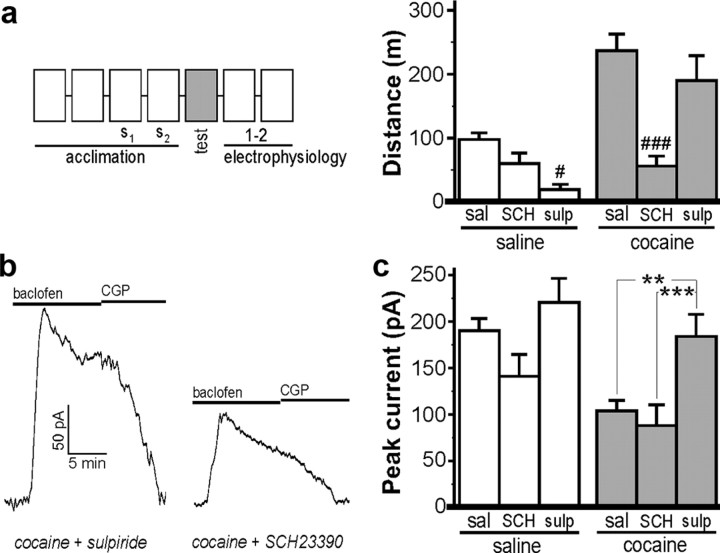

Systemic cocaine increases DA levels in the VTA and in downstream targets of the VTA, including the NAcc (Einhorn et al., 1988). As such, a separate cohort of mice was challenged with cocaine or saline following pretreatment (intraperitoneally; 30 min) with the D1/5R antagonist SCH23390 or the D2/3R antagonist sulpiride to test whether the cocaine-induced suppression of GABABR–Girk signaling was mediated by activation of DA signaling pathways. SCH23390 (0.18 mg/kg, i.p.) tempered saline-induced motor activity while completely blocking cocaine-induced activity, consistent with previously published reports in mice (Cabib et al., 1991) (Fig. 4a). SCH23390 pretreatment did not, however, prevent the adaptation in baclofen-evoked currents in VTA DA neurons measured 1–2 d after injection (Fig. 4b,c). Sulpiride pretreatment (50 mg/kg, i.p.), in contrast, inhibited saline-induced motor activity but had no effect on cocaine-induced activity, also consistent with published reports (Cabib et al., 1991; Chausmer and Katz, 2001). Sulpiride pretreatment blocked the acute cocaine-induced suppression of baclofen-evoked currents in VTA DA neurons (Fig. 4b,c). Thus, the cocaine-induced suppression of GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons is dependent on D2/3R, but not D1/5R, activation.

Figure 4.

The cocaine-induced suppression of GABABR–Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons is D2/3R dependent. a, Total distance traveled on test day by mice (6–25 per group) following administration of saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg), 30 min after pretreatment with saline (sal), the D1/5 DA receptor (D1/5R) antagonist SCH23390 (SCH) (0.18 mg/kg), or the D2/3R antagonist sulpiride (sulp) (50 mg/kg). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant pretreatment by drug (saline, cocaine) interaction (F(2,61) = 4.7; p < 0.05). Only within-drug comparisons are shown. #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001, respectively, versus sal pretreatment group. b, Representative currents evoked by 200 μm baclofen in VTA DA neurons from cocaine-treated mice pretreated with either SCH23390 or sulpiride. c, Mean baclofen-induced somatodendritic currents in neurons from saline- and cocaine-treated mice (n = 7–24 per group). All recordings were made 1–2 d after test day injection. Two-way ANOVA revealed main effects of pretreatment (F(2,72) = 6.9; p < 0.01) and drug (F(1,72) = 11.1; p < 0.01), but no interaction (F(2,72) = 0.8; p = 0.5). As such, only within-drug comparisons are presented. Note that pretreatment condition had no significant effect on baclofen-induced currents among saline-treated mice. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, respectively. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

The present study provides the first indication that a single exposure to cocaine triggers a robust suppression of somatodendritic Girk signaling in VTA (but not SN) DA neurons, an effect that persists up to 4 d following drug exposure and is paralleled by enhanced glutamatergic signaling in the same neurons. Moreover, the magnitude of the cocaine-induced suppression of somatodendritic Girk signaling was comparable following acute or repeated exposure. This reduction is mirrored by a cocaine-induced decrease in the density of Girk2-containing channels at the plasma membrane of TH-positive dendrites. Furthermore, the acute cocaine-induced suppression of somatodendritic Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons is dependent on D2/3R activation, as prior blockade of D2/3R- but not D1/5R-dependent signaling prevented this adaptation.

Acute exposure to cocaine and other drugs of abuse triggers an increase in glutamatergic neurotransmission in VTA DA neurons, an adaptation that requires NMDA receptor activation, involves the synaptic insertion of GluR1-containing AMPA receptors, and persists for up to 5 d (Ungless et al., 2001; Bellone and Lüscher, 2006; Argilli et al., 2008). Acute exposure to cocaine and other drugs of abuse also impairs the ability of VTA DA neurons to express long-term potentiation of GABAA receptor-dependent synaptic transmission, an adaptation that recovers within 5 d of drug injection (Niehaus et al., 2010). Here, we demonstrate an analogous temporal pattern of reduced inhibitory metabotropic signaling within VTA DA neurons following acute cocaine exposure. Similar to cocaine-induced adaptations in excitatory signaling (Borgland et al., 2004), this suppression was not further enhanced or prolonged by additional cocaine exposure, suggesting that a single cocaine injection is sufficient to saturate the plasticity of inhibitory metabotropic signaling in VTA DA neurons.

Evidence indicates that synaptic plasticity in DA neurons of the VTA following early cocaine exposure plays an important role in the development of addiction by facilitating the shift in the threshold for the induction of plasticity within downstream targets of the VTA, such as the NAc and PFC (Everitt and Wolf, 2002; Mameli et al., 2009). Weakening of inhibitory feedback onto VTA DA neurons and diminished autoreceptor tone, as is predicted with the cocaine-induced suppression of Girk signaling, is consistent with the behavioral sensitization seen with repeated cocaine exposure. But while behavioral sensitization is a long-lasting phenomenon, the strength of Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons recovers within 10–12 d of the final injection in a repeated cocaine administration regimen. Thus, the cocaine-induced suppression of Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons may contribute to the induction of behavioral sensitization, but it is not required for the expression of long-lasting sensitization.

Previous work has shown that Girk channels mediate almost all of the somatodendritic current responses to GABABR and D2R stimulation in midbrain DA neurons (Beckstead et al., 2004; Cruz et al., 2004; Labouèbe et al., 2007; Arora et al., 2010). The Girk channel found in VTA DA neurons consists of Girk2 and Girk3, a subtype exhibiting reduced sensitivity to Gβγ activation (Jelacic et al., 2000; Cruz et al., 2004; Labouèbe et al., 2007). This, together with the selective expression of Rgs2 in VTA DA neurons, underlies the relative insensitivity of Girk channels in VTA DA neurons to GABABR stimulation (Labouèbe et al., 2007). While exposure to drugs of abuse can influence the expression of RGS proteins and trigger changes in subunit composition of ionotropic glutamate receptors (Bellone and Lüscher, 2006; Labouèbe et al., 2007), changes in Girk channel subunit composition or altered expression of RGS proteins does not likely explain the impact of acute cocaine on Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons. Rather, the reduction in GABABR–Girk (and D2R–Girk) signaling seen following acute cocaine exposure is most simply explained by a reduction in the density of Girk2-containing channels on the somatodendritic membrane of VTA DA neurons.

Pretreatment with DA receptor antagonists revealed differences in the signaling mechanisms underlying the motor-stimulatory effect of cocaine (D1/5R dependent) and the cocaine-induced adaptation in GABABR–Girk signaling (D2/3R dependent). Systemic cocaine administration promotes elevated DA levels in the VTA, which provides inhibitory feedback mediated by D2R expressed in VTA DA neurons (autoreceptors). While cocaine-induced stimulation of D2R autoreceptors may mediate the suppression of Girk signaling in VTA DA neurons, this adaptation may also be triggered by stimulation of D2/3R activation in striatal or cortical brain regions that link back to the VTA.

In the VTA, suppression of somatodendritic Girk signaling is predicted to complement the well described and parallel adaptations in ionotropic glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling, all of which serve to facilitate the output of VTA DA neurons and increase their vulnerability to drugs of abuse following an initial exposure. Future efforts to define the anatomic, genetic, and temporal bases of these disparate adaptations in the VTA may provide important insight into how early and transient cocaine-induced adaptations facilitate the longer-lasting and stable changes that promote chronic cocaine intake.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 MH061933 (K.W.), P50 DA011806 (K.W.), R21 DA029343 (K.W.), T32 DA007234 (K.M.), T32 DA007097 (M.H.), and R01 DA017758 (M.W.W.), and Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grants BFU2009-08404/BFI and CONSOLIDER-Ingenio CSD2008-00005 (R.L.). We thank Daniele Young for assistance with the mouse colony. We also thank Rebecca Speltz-Paiz and Ruichi Shigemoto for their technical assistance.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Ackerman JM, White FJ. A10 somatodendritic dopamine autoreceptor sensitivity following withdrawal from repeated cocaine treatment. Neurosci Lett. 1990;117:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90141-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado C, Colón J, Ciruela F, Schlaudraff F, Cabañero MJ, Perry C, Watanabe M, Liss B, Wickman K, Luján R. Cell type-specific subunit composition of G protein-gated potassium channels in the cerebellum. J Neurochem. 2008;105:497–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argilli E, Sibley DR, Malenka RC, England PM, Bonci A. Mechanism and time course of cocaine-induced long-term potentiation in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9092–9100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1001-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora D, Haluk DM, Kourrich S, Pravetoni M, Fernández-Alacid L, Nicolau JC, Luján R, Wickman K. Altered neurotransmission in the mesolimbic reward system of Girk mice. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1487–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead MJ, Grandy DK, Wickman K, Williams JT. Vesicular dopamine release elicits an inhibitory postsynaptic current in midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2004;42:939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone C, Lüscher C. Cocaine triggered AMPA receptor redistribution is reversed in vivo by mGluR-dependent long-term depression. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nn1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, Dunnett SB. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Malenka RC, Bonci A. Acute and chronic cocaine-induced potentiation of synaptic strength in the ventral tegmental area: electrophysiological and behavioral correlates in individual rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7482–7490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1312-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabib S, Castellano C, Cestari V, Filibeck U, Puglisi-Allegra S. D1 and D2 receptor antagonists differently affect cocaine-induced locomotor hyperactivity in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;105:335–339. doi: 10.1007/BF02244427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chausmer AL, Katz JL. The role of D2-like dopamine receptors in the locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s002130000668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Qian X, Ehlers M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Neuronal activity regulates phosphorylation-dependent surface delivery of G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:629–634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811615106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz HG, Ivanova T, Lunn ML, Stoffel M, Slesinger PA, Lüscher C. Bi-directional effects of GABAB receptor agonists on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nn1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn LC, Johansen PA, White FJ. Electrophysiological effects of cocaine in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system: studies in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1988;8:100–112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Wolf ME. Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems persepctive. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3312–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Onn SP. Morphology and electrophysiological properties of immunocytochemically identified rat dopamine neurons recorded in vitro. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3463–3481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03463.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelacic TM, Kennedy ME, Wickman K, Clapham DE. Functional and biochemical evidence for G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels composed of GIRK2 and GIRK3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36211–36216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Two types of neurone in the rat ventral tegmental area and their synaptic inputs. J Physiol. 1992;450:455–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE. Memory and addiction: shared neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms. Neuron. 2004;44:161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyrakh L, Luján R, Colón J, Karschin C, Kurachi Y, Karschin A, Wickman K. Molecular and cellular diversity of neuronal G-protein-gated patassium channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11468–11478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3484-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, Unterwald EM. Chronic cocaine administration decreases the functional coupling of GABAB receptors in the rat ventral tegmental area as measured by baclofen-stimulated 35S-GTPγS binding. Life Sci. 2001;69:1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouèbe G, Lomazzi M, Cruz HG, Creton C, Luján R, Li M, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Watanabe M, Wickman K, Boyer SB, Slesinger PA, Lüscher C. RGS2 modulates coupling between GABAB receptors and GIRK channels in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1559–1568. doi: 10.1038/nn2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔC(T) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mameli M, Halbout B, Creton C, Engblom D, Parkitna JR, Spanagel R, Lüscher C. Cocaine-evoked synaptic plasticity: persistence in the VTA triggers adaptations in the NAc. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1036–1041. doi: 10.1038/nn.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathon DS, Lesscher HM, Gerrits MA, Kamal A, Pintar JE, Schuller AG, Spruijt BM, Burbach JP, Smidt MP, van Ree JM, Ramakers GM. Increased Gabaergic input to ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons associated with decreased cocaine reinforcement in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2005;130:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassirpour R, Bahima L, Lalive AL, Lüscher C, Luján R, Slesinger PA. Morphine- and CaMKII-dependent enhancement of GIRK channel signaling in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13419–13430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2966-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhoff H, Neu A, Liss B, Roeper J. Ih channels contribute to the different functional properties of identified dopaminergic subpopulations in the midbrain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1290–1302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01290.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus JL, Murali M, Kauer JA. Drugs of abuse and stress impair LTP at inhibitory synapses in the ventral tegmental area. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Laterodorsal tegmental projections to identified cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:217–235. doi: 10.1002/cne.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravetoni M, Wickman K. Behavioral characterization of mice lacking GIRK/Kir3 channel subunits. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:523–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96:103–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita S, Johnson SW, North RA. Synaptic inputs to GABAA and GABAB receptors originate from discrete afferent neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1992;134:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90518-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Whistler JL, Malenka RC, Bonci A. Single cocaine exposure in vivo induces long-term potentiation in dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;411:583–587. doi: 10.1038/35079077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]