Abstract

Objective

To determine sustained effectiveness in reducing depression symptoms and improving depression care one year following intervention completion.

Method

Of 387 low-income, predominantly Hispanic diabetes patients with major depression symptoms randomized to 12-month socio-culturally adapted collaborative care (psychotherapy and/or antidepressants, telephone symptom monitoring/relapse prevention) or enhanced usual care, 264 patients completed two-year follow-up. Depression symptoms (SCL-20, PHQ-9), treatment receipt, diabetes symptoms, and quality of life were assessed 24 months post-enrollment using intent-to-treat analyses.

Results

At 24 months, more intervention patients received ongoing antidepressant treatment (38% v 25%, chi-square=5.11, df=1, P=0.02); sustained depression symptom improvement (SCL-20<0.5 (adjusted OR=2.06, 95%CI=1.09–3.90, P=0.03), SCL-20 score (adjusted mean difference −0.22, P=0.001), and PHQ-9 ≥50% reduction (adjusted OR=1.87, 95%CI=1.05–3.32, P=0.03). Over 2 years, improved effects were found in significant study group by time interaction for SF-12 mental health, SDS functional impairment, diabetes symptoms, anxiety, and socioeconomic stressors (P=0.02 for SDS, P<0.0001 for all others); however, group differences narrowed over time and were no longer significant at 24 months.

Conclusions

Socio-culturally tailored collaborative care that included maintenance antidepressant medication, ongoing symptom monitoring and behavioral activation relapse prevention was associated with depression improvement over 24 months for predominantly Hispanic patients in primary safety net care.

Keywords: Depression, Diabetes, Collaborative Care, Safety Net, Hispanic

INTRODUCTION

Among patients with diabetes there is a two-fold higher risk of comorbid depression compared to the general population and depression is often persistent and severe [1]. Hispanics have a higher prevalence of diabetes compared to non-Hispanic whites [1], high comorbid depression rates [2], and greater risk of cardiovascular illness, functional disability, and mortality [3]. Moreover, depression is frequently chronic and recurrent, even after depression treatment [4] and among patients with diabetes, rates of relapse as high as 80% have been reported over five years, suggesting a need for ongoing symptom monitoring and behavioral activation [5]. However, Hispanics are less likely to be diagnosed accurately or to receive depression care often due to socioeconomic barriers, early antidepressant discontinuation or nonadherence associated with cultural preferences for psychotherapy and stigma, addiction and side-effects fears, and socio-economic stress [6–10].

Research demonstrates that Hispanic populations apply culturally-normative conceptual models of depression with respect to treatment preferences for psychotherapy and adherence, while navigating barriers to care such as language and literacy. In addition, low-income patients are also more likely to experience ongoing social and economic stress that may contribute to both acute depression and its persistence and recurrence, while also impeding access to care over time [11]. While socio-culturally adapted care models improve depression outcomes in low-income and Hispanic patients, post-trial sustainable symptom improvement and care management remain important research questions [12–17].

We previously reported 6, 12 and 18 month results from a randomized Multifaceted Diabetes and Depression Program (MDDP), a collaborative care treatment program designed for low-income, predominantly Hispanic depressed diabetes patients receiving care within community safety net clinics [12]. Patients meeting criteria for clinically significant depression randomized to collaborative care were more likely to receive depression care, had significantly greater improvement in depression symptoms and quality-of-life (QoL), reduced socioeconomic stress and reported fewer diabetes symptoms over the initial 18-month period [13]. Here we report outcomes over a 24-month period. We hypothesize that, at 24 months, intervention patients would experience more lasting depression improvement than controls.

METHODS

The MDDP trial was approved by the University of Southern California IRB. Patients provided verbal depression screening consent (August 2005–August 2007); 387 patients provided written informed study consent and completed a baseline interview (79% in-person, 21% by phone) prior to computer-driven randomization to MDDP (INT) or enhanced usual care (EUC). Eligible patients were ≥18 years, English or Spanish speaking, and endorsed one of the 2 cardinal depression symptoms more than half the days to nearly every day over the last two weeks and scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 indicating clinically significant depression. Study eligibility screening excluded patients with acute suicidal ideation, alcohol abuse (a score of 8 or greater on the AUDIT alcohol assessment) or self-reported recent lithium/antipsychotic medication use.

Because patients may not perceive depression as a biomedical condition and may perceive depression as stigmatizing (resulting in less acceptance of antidepressant medication (AM) [7,8]) and family members can encourage or deter depression care [6], INT and EUC patients were given patient and family depression educational pamphlets (Spanish or English). In addition, because safety net clinic patients encounter difficulties in navigating clinic systems and meeting basic socio-economic needs, both study groups were given a written list of clinic, community mental health, financial, social services, transportation, and child care resources. Clinic primary care physicians (PCPs) participated in a didactic on a care management stepped care algorithm, were informed of patients’ PHQ-9 score and study participation, and for EUC patients could prescribe AMs, provide counseling or refer to community mental health care.

MDDP is based on evidence-based collaborative care depression practice guidelines for primary care and is designed to improve disparities in access to depression care in safety net care. The 12-month intervention included: 1) acute treatment and relapse prevention; 2) patient initial choice of AM or problem solving treatment (PST); 3) application of a stepped care treatment algorithm; 4) AM prescribed by the PCPs; 5) PST provided by graduate social work diabetes depression clinical specialists (DDCS); and 6) Relapse prevention via DDCS monthly telephone symptom monitoring and behavioral activation prompts, booster PST sessions if indicated, and response to patient care system or community resource navigation questions by DDCS and/or patient navigator. A study psychiatrist provided weekly telephone DDCS supervision and, if requested, telephone PCP AM consultation. Over the study 12 month intervention, 84% of intervention patients received depression treatment (49 PST, 9 AM, 104 both; 63 (56%) with AM change or dosage increment) versus 32.5% of EUC patients (37 AM, 11 self-reported counseling, 15 both).

MDDP included socio-cultural adaptations, such as bilingual social workers, and PST aligned with perceived stress-related needs and cultural values aimed at stigma treatment adherence reduction. PST materials were culturally adapted in eight areas: Language –literacy and idiomatic; Persons – bilingual staff; Metaphors – use of sayings or “dichos” in treatment sessions; Content – cultural values recognition and knowledge; Concepts – treatment concepts sensitive and consistent with culture and context; Goals –sensitivity to cultural values; Methods – PST handouts and examples consistent with culture; Context – consideration of patient’s health, socio-economic, and home/family environment [11,17].

Data Collection

Follow-up telephone interviews at 6, 12, 18, 24 months were conducted by interviewers blinded to study group assignment. Outcome variables included depression scores (SCL-20, PHQ-9), treatment response (≥50% reduction from baseline score), complete remission (SCL-20 score <0.5), depression treatment receipt, anxiety (Brief Symptom Inventory), functional impairment (Sheehan Disability Scale), and SF-12 QoL physical and mental health [18]. AM use over the preceding 6 months was obtained from electronic pharmacy records and patient self-report at 24 months, with 14% discordant between data sources (7% from pharmacy records only; 6% from self-report only) (Kappa coefficient=0.66). Diabetes clinical outcomes were assessed using: the Whitty 9-item questionnaire to assess diabetes symptoms, which has been demonstrated to change over time with effective diabetes treatment [19]; glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) obtained from medical records (the last test done within 3 months of each follow up interview); the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire to measure self-reported adherence [20]; self-reported weight and height (BMI); diabetes complications; and comorbid physical illness. Also assessed were self-reported socioeconomic stressors (financial, work, family, legal problems, and community violence worry) and barriers to depression care.

Analyses

Intent-to-treat analysis was conducted to evaluate group differences. Logistic regression models were used for dichotomous outcomes, with GEE models evaluating intervention effects over time (from baseline to 24 months). Sharing the same assumptions as the logistic regression model, the GEE model allows autoregressive correlation structure of repeated observations within the same patients be considered in the modeling process. Robust estimation of parameter estimates were adopted since the robust estimation produces consistent point estimates and standard errors even if the working correlation matrix was misspecified [21–23]. General linear mixed-effects models [24] were fitted with longitudinal continuous data from baseline to 24 months, specified with unstructured covariance to account for within-patient correlations of repeated observations over time. All logistic regressions, GEE models, and linear mixed-effects models were adjusted for study site, birth place (US born vs. others), language (Spanish vs. English), years in US (<10 vs. ≥10), and baseline SCL-20 score, dysthymia, and number of socioeconomic stressors. All analyses were conducted at 0.05 significance level (2-tailed) using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Hot Deck imputations as well as Predictive-Model based multiple imputations [25–26] implemented in SOLAS version 3.2 [27] were used to validate analyses on intervention versus EUC evaluation. Imputed data results were consistent with the results analyzed with all-available data, thus, we present all-available data results.

RESULTS

Study Sample

The sample (n=387) was 96% Hispanic, 82% female, with a mean age of 54 (SD=8.7), 91% foreign born (Mexico 83%; Central America 13%; with 90% having lived in the US ≥10 years), and 82% had not completed high school. Almost all (98%) had type 2 diabetes, with high HbA1c levels (average 9.03% in the last test done before enrollment), and had ≥1 self-reported diabetes complications (83%). At baseline, study groups did not differ significantly on AM/counseling receipt; depression severity scores; or HbA1c, BMI, or ICD-9 diagnoses in the last 6 months; over 50% of patients had moderate to severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥15) and nearly 19% reported prior depression.

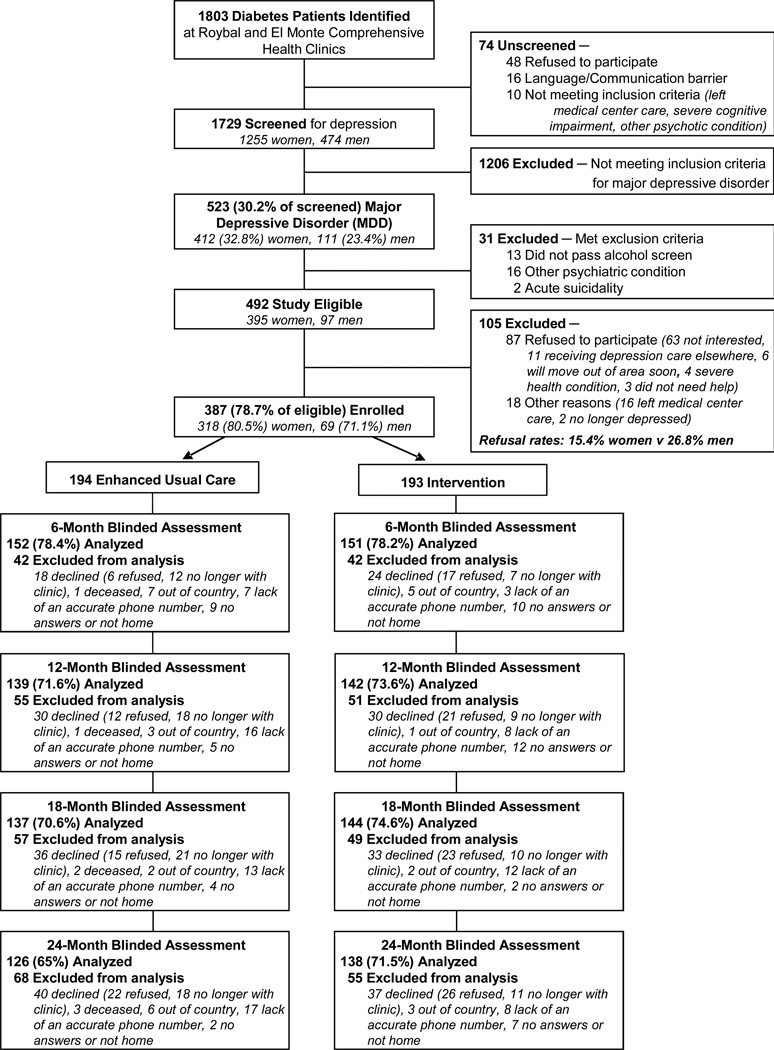

Of 387 patients enrolled at baseline, 24 month attrition totaled 123 (31.8%) (Figure 1). Of these, 48 (12.4%) declined continuing study participation, 29 (7.5%) were no longer receiving care at the clinic, 9 (2.3%) no longer living in the US, 3 (<1%) were deceased, and 34 (8.8%) could not be located. Although average HbA1C values did not differ between attrition and retention groups (9.38% vs. 8.73%, P=0.20), relatively more attrition patients had an HbA1C greater than 7% compared to retention patients (56.9% vs. 43.1%, P=0.02). All other baseline depression, clinical and demographic characteristics were similar between attrition and retention groups.

Figure 1.

MDDP CONSORT Diagram

Depression Care

At 24 months, MDDP patients were significantly more likely to be receiving AM (38% vs. 25%, P=0.02), and to report high satisfaction with their emotional care (89% vs. 74%, P=0.002). (Table 1) There were no significant group differences in self-reported psychotherapy receipt or in barriers to depression care. Most frequently reported barriers were forgetting appointments or taking AM (32%), transportation (26%), practical barriers (22%), fears of antidepressant addiction (20%), managing multiple health problems (15%), and treatment cost concerns (15%).

Table 1.

Depression Treatment and Satisfaction 1 Year after MDDP Trial Completion

| 24-month Interview, N=264 |

EUC, N=126 |

INT, N=138 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | Chi-Square [df=1] |

P | |

| Depression Treatment Received | |||||

| During the Past 6 Monthsa | |||||

| Antidepressant | 85 (32.2) | 32 (25.4) | 53 (38.4) | 5.11 | 0.02 |

| psychotherapy or counseling | 42 (15.9) | 19 (15.1) | 23 (16.7) | 0.12 | 0.72 |

| Antidepressant and psychotherapy/counseling | 25 (9.5) | 10 (7.9) | 15 (10.9) | 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Any depression treatment (antidepressant medication, psychotherapy or counseling) | 102 (38.6) | 41 (32.5) | 61 (44.2) | 3.78 | 0.05 |

| Satisfaction with depression care (satisfied, very satisfied) | 212 (81.9) | 92 (74.2) | 120 (88.9) | 9.40 | 0.002 |

Antidepressant use over the past 6 months was obtained from pharmacy pick-up electronic records and psychotherapy/counseling via patient self-report at 24 months.

Depression Improvement

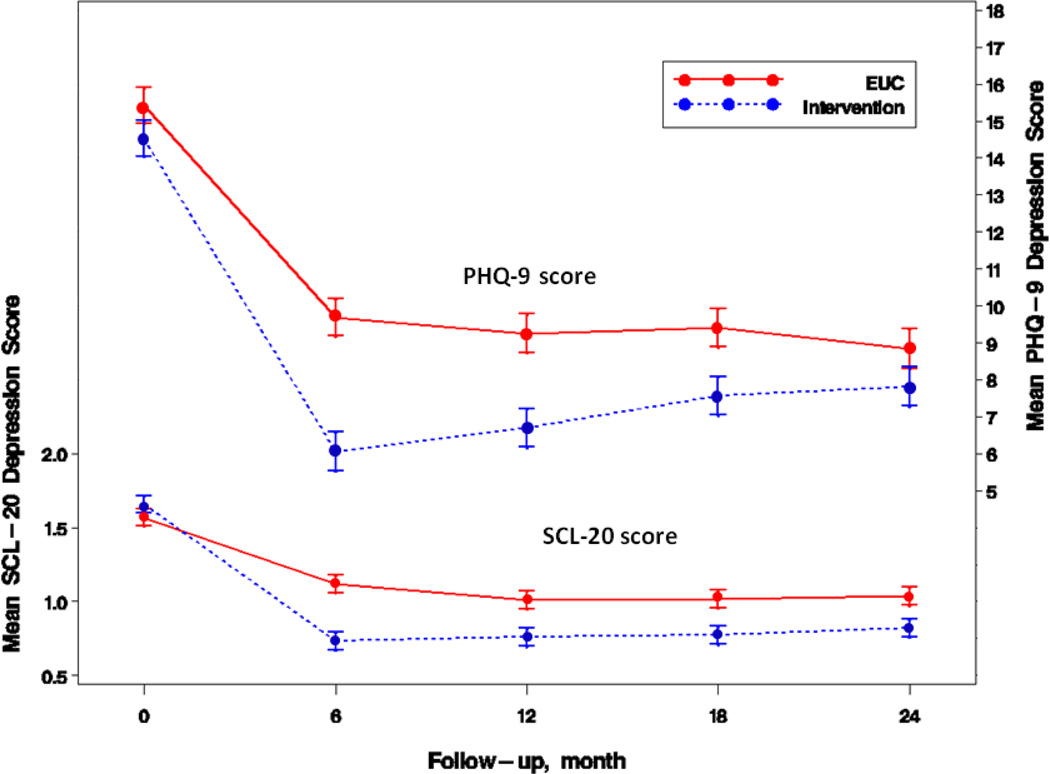

At 24 months, MDDP patients experienced significantly better sustained depression symptom improvement in SCL-20<0.5 (adjusted OR=2.06, 95%CI=1.09–3.90, P=0.03) and SCL-20 score (adjusted mean difference −0.22, P=0.001), as well as ≥50% PHQ-9 reduction (adjusted OR=1.87, 95%CI=1.05–3.32, P=0.03). (Figure 2) (Table 2) While the greatest differences occurred at 12 months and the group differences narrowed over time, the overall MDDP effects from baseline to 24 months (as reflected by the significant study group by time interaction) were significant for ≥50% PHQ-9 reduction, PHQ-9<5, PHQ-9≥10, and continuous SCL-20, PHQ-9 scores.

Figure 2.

Intervention vs control differences in mean depression scores

Mean depression scores from SCL-20 (range, 0–4) and PHQ-9 (range, 0–27) adjusted for study site, birth place, language, years in US, and baseline SCL-20 score, dysthymia, and number of stressors. Error bars indicate standard errors. Significant group difference in mean SCL-20 was observed at all follow-up points (P≤.001), as well as significant group difference in mean PHQ-9 at 6, 12, and 18 months (P≤.001).

Table 2.

Depression Outcomes

| Enhanced Usual Care |

Intervention | Adjusted Analysis for Intervention vs. Enhanced Usual Carea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | time by group interaction, Pb |

|

| ≥50% SCL-20 Reduction | 0.13 | ||||

| 12-month follow-up | 59 (42.4) | 88 (62.0) | 2.59 (1.51 – 4.46) | 0.001 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 60 (43.8) | 89 (61.8) | 2.64 (1.52 – 4.6) | 0.001 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 62 (49.2) | 80 (58.0) | 1.69 (0.97 – 2.96) | 0.06 | |

| ≥50% PHQ-9 Reduction | 0.01 | ||||

| 12-month follow-up | 66 (47.5) | 86 (60.6) | 3.35 (1.87 – 6.03) | <0.0001 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 63 (46.0) | 82 (56.9) | 2.89 (1.63 – 5.12) | <0.001 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 65 (51.6) | 74 (53.6) | 1.87 (1.05 – 3.32) | 0.03 | |

| Remission (SCL-20 <0.5) | 0.22 | ||||

| 12-month follow-up | 49 (35.3) | 56 (39.4) | 2.07 (1.17 – 3.66) | 0.01 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 48 (35.0) | 58 (40.3) | 2.66 (1.45 – 4.9) | 0.002 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 41 (32.5) | 46 (33.3) | 2.06 (1.09 – 3.9) | 0.03 | |

| PHQ-9 <5 | 0.02 | ||||

| 12-month follow-up | 40 (28.8) | 55 (38.7) | 3 (1.62 – 5.53) | <0.001 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 43 (31.4) | 51 (35.4) | 2.36 (1.27 – 4.4) | 0.01 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 42 (33.3) | 41 (29.7) | 1.31 (0.72 – 2.38) | 0.38 | |

| PHQ-9 ≥10 | 0.003 | ||||

| 12-month follow-up | 54 (38.8) | 40 (28.2) | 0.37 (0.2 – 0.66) | 0.001 | |

| 18-month follow-up | 62 (45.3) | 49 (34.0) | 0.34 (0.19 – 0.61) | <0.001 | |

| 24-month follow-up | 45 (35.7) | 55 (39.9) | 0.66 (0.37 – 1.2) | 0.17 | |

Number of patients analyzed at 12, 18, and 24 months are 139, 137, and 126 EUC; 142, 144, and 138 INT.

Logistic regression models adjusted for study clinic, birth place (US born vs immigrant), language (Spanish vs English), years in US (<10 v ≥10), and baseline SCL-20 score, dysthymia, and number of socioeconomic stressors

P value derived from GEE model adjusted for the same set of covariates

Quality of Life and Diabetes Clinical Outcomes

While an overall improved MDDP effect is reflected by significant study group by time interaction (Table 3) for SF-12 mental health, SDS functional impairment, anxiety, number of socioeconomic stressors, and diabetes symptoms (P=0.02 for SDS, P<0.0001 for all others); group differences narrowed over time and were no longer significant at 24 months. There was no over time effect in diabetes complications where group differences disappeared after 12 months. No group differences were found in HbA1c, or mean self-care management scores over time or at each follow-up.

Table 3.

Quality of Life and Diabetes Clinical Outcomesa

| Enhanced Usual Care, Mean (SE) Intervention, Mean (SE) Mean Difference (95% CI) |

P | |

|---|---|---|

| time by group interaction, P | ||

| SF-12 Mental Health | ||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 42.00 (1.15) 48.22 (1.15) 6.22 (3.79 – 8.64) |

||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 42.09 (1.14) 46.26 (1.14) 4.17 (1.75 – 6.60) |

||

| 0.001 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 42.48 (1.17) 44.76 (1.15) 2.28 (−0.21 – 4.77) |

||

| 0.07 | ||

| SF-12 Physical Function | ||

| 0.06 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 37.93 (1.19) 38.07 (1.20) 0.13 (−2.26 – 2.52) |

||

| 0.91 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 38.56 (1.19) 39.10 (1.19) 0.55 (−1.85 – 2.94) |

||

| 0.65 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 38.35 (1.21) 38.43 (1.20) 0.08 (−2.36 – 2.53) |

||

| 0.95 | ||

| SDS Functional Impairment | ||

| 0.02 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 4.17 (0.30) 3.23 (0.30) −0.94 (−1.58 – −0.30) |

||

| 0.004 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 4.14 (0.30) 3.53 (0.30) 0.61 (−1.25 – 0.03) |

||

| 0.06 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 3.86 (0.31) 3.89 (0.30) 0.02 (−0.64 – 0.68) |

||

| 0.95 | ||

| BSI Anxiety Scores | ||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 4.68 (0.44) 2.39 (0.44) 2.29 (−3.22 – −1.37) |

||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 4.56 (0.44) 3.32 (0.44) −1.23 (−2.16 – −0.31) |

||

| 0.01 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 3.84 (0.45) 2.88 (0.45) 0.95 (−1.90 – −0.00) |

||

| 0.05 | ||

| Number of Socioeconomic Stressors | ||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 2.97 (0.20) 2.11 (0.20) −0.87 (−1.31 – −0.42) |

||

| 0.0001 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 2.93 (0.20) 2.31 (0.20) 0.62 (−1.07 – −0.18) |

||

| 0.01 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 2.87 (0.20) 2.24 (0.20) 0.64 (−1.09 – −0.18) |

||

| 0.01 | ||

| HbA1c | ||

| 0.80 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 8.87 (0.27) 8.88 (0.27) 0.01 (−0.50 – 0.51) |

||

| 0.98 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 8.69 (0.28) 8.86 (0.28) 0.17 (−0.37 – 0.70) |

||

| 0.54 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 8.87 (0.29) 9.10 (0.29) 0.23 (−0.34 – 0.81) |

||

| 0.42 | ||

| Diabetes Symptoms | ||

| <0.0001 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 1.87 (0.07) 1.69 (0.07) −0.18 (−0.33 – −0.04) |

||

| 0.01 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 1.89 (0.07) 1.79 (0.07) −0.10 (−0.24 – 0.04) |

||

| 0.17 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 1.84 (0.07) 1.76 (0.07) −0.08 (−0.23 – 0.06) |

||

| 0.27 | ||

| Diabetes Complications | ||

| 0.13 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 1.48 (0.12) 1.20 (0.12) 0.28 (−0.53 – −0.04) |

||

| 0.02 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 1.41 (0.12) 1.42 (0.12) 0.02 (−0.23 – 0.26) |

||

| 0.90 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 1.60 (0.12) 1.40 (0.12) −0.20 (−0.45 – 0.05) |

||

| 0.12 | ||

| Diabetes Selfcare Management | ||

| 0.84 | ||

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| 3.34 (0.15) 3.31 (0.15) −0.03 (−0.35 – 0.29) |

||

| 0.86 | ||

| 18-month follow-up | ||

| 3.50 (0.15) 3.67 (0.15) 0.17 (−0.16 – 0.49) |

||

| 0.31 | ||

| 24-month follow-up | ||

| 3.41 (0.16) 3.60 (0.15) 0.19 (−0.14 – 0.52) |

||

| 0.26 | ||

Number of patients analyzed at 12, 18, and 24 months are 139, 137, and 126 EUC; 142, 144, and 138 INT, respectively. Number of patients with HbA1c measure are 124, 100, and 74 EUC; 113, 91, and 78 INT at 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively.

Mixed-effect models adjusted for study clinic, birth place (US born vs immigrant), language (Spanish vs English), years in US (<10 v ≥10), and baseline SCL-20 score, dysthymia, and number of socioeconomic stressors

DISCUSSION

The socio-culturally adapted MDDP collaborative care model resulted in long-term improvements in antidepressant use and depression symptoms, and greater satisfaction with depression care. The 24-month outcomes were consistent with our previously reported 18-month findings [13], our trial with predominantly Hispanic cancer patients [15], the collaborative care IMPACT study [28], and the collaborative care Pathways study [29]. Despite the lack of access to a depression care manager post-intervention, improvements were sustained over time. This may be due to the relapse prevention strategies that intervention patients received including symptom monitoring, behavioral activation with a PST self management plan, targeted recommendations for maintenance antidepressant medications and a patient-specific plan and community resource list for whom to contact if depression worsened.

While long-term MDDP depression results are encouraging, an increase in diabetes symptoms was significantly associated with 24-month outcomes. Recent reports indicate that the biologic effects of depression on diabetes clinical outcomes such as glycemic, blood pressure, or lipid control requires further study [30–32].

The MDDP study has provided convincing data that confirms that low-income, predominantly Hispanic diabetes patients accept and benefit from collaborative depression care management and the clinic staff report high rates of satisfaction with the model and a strong desire to sustain effective depression care management. At the same time, staff and organizational leaders raised critical questions about the uptake and sustainability of the MDDP model. While total health care expenditures among patients with diabetes and depression are up to two to four-fold higher than for non-depressed patients [33], safety net care systems present critical questions regarding depression care cost, collaborative provider communication mechanisms, and patient treatment preferences. To address these sustainability issues, we are currently conducting a sustainability quasi-experimental trial of 1500 diabetes patients in 9 Los Angeles public primary care safety net clinics to address patient, provider, and organizational factors including, depression and diabetes clinical outcomes, patient and provider use of and satisfaction with health technologies such as Automated Speech Recognition depression long-term symptom monitoring and a collaborative provider facilitated communication web-based registry. We also are in the process of conducting cost analyses of the MDDP model.

Limitations

Study limitations include the possibility that MDDP care improved treatment of enhanced usual care patients because the same physicians treated both groups, while the 32% attrition rate may have limited improvement effect sizes. Despite practical and culturally sensitive strategies to reduce attrition, at 24 months, voluntary dropout (in part related to declining health and ongoing or increasing socioeconomic stress), and inability to locate patients (attributable to the geographic mobility of this safety net population) resulted in relatively high post-baseline attrition.

Conclusions

The study findings suggest that collaborative care results in long-term sustained depression improvement among low-income, minority diabetes patients in safety net care, while patients initially prefer counseling over antidepressant medication, or in combination with medication. Moreover, results underscore the need for routine depression screening and treatment, plus ongoing symptom monitoring, and treatment adjustments over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study is supported by R01 MH068468 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI, Dr. Ell).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: NCT00709150, clinicaltrials.gov/ct/gui

Disclosures: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Disclaimer: Dr. Kapetanovic contributed to this article in his personal capacity. The views expressed are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or United States Government.

Contributor Information

Kathleen Ell, Email: ell@usc.edu.

Wayne Katon, Email: wkaton@u.washington.edu.

Bin Xie, Email: bin.xie@cgu.edu.

Pey-Jiuan Lee, Email: peylee@usc.edu.

Suad Kapetanovic, Email: kapetanovics@mail.nih.gov.

Jeffery Guterman, Email: jguterman@ladhs.org.

Chih-Ping Chou, Email: cchou@usc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lanting LC, Joung I, Mackenbach JP, Lamberts SW, Boostma AH. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2280–2288. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C, Ford ES, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of depression among U.S. adults with diabetes: findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:105–107. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Depression and glycemic control in Hispanic primary care patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959–985. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lustman P, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Clouse RE. The course of major depression in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:138–143. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Azúcar y nervios: explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Ang A. Addressing stigma of depression in Latino primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez Y, Garcia E, Franks P, Jerant A, Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Depression treatment preferences of Hispanic individuals: exploring the influence of ethnicity, language, and explanatory models. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:39–50. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, et al. Depression, correlates of depression and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecological cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karasz A, Watking L. Conceptual models of treatment in depressed Hispanic patients. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:527–533. doi: 10.1370/afm.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ell K, Katon W, Cabassa LJ, et al. Depression and diabetes among low-income Hispanics: design elements of a socio-culturally adapted collaborative care model randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2009;39:113–132. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.2.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income predominantly Hispanics with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:706–713. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ell K, Xie B, Kapetanovic S, et al. One-year follow-up of collaborative depression care for low-income, predominantly Hispanic patients with cancer. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:162–170. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palinkas L, Ell K, Hansen M, Cabassa L, Wells A. Sustainability of collaborative care interventions in primary care settings. J Soc Work. 2011;11:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Hay J, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care in addressing depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatr Services. 2010;61:1112–1118. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitty P, Steen N, Eccles M, et al. A new self-completion outcome measure for diabetes: is it responsive to change? Qual Life Res. 1997;6:407–413. doi: 10.1023/a:1018443628933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Russell E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horton NJ, Lipsitz SR. Review of software to fit generalized estimating equation regression models. Am Statistician. 1999;53:160–169. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang KY, Beaty TH, Cohen BH. Application of odds ratio regression models for assessing familial aggregation from case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:678–683. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeger SL, Liang KY. An overview of methods for the analysis of longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1992;11:1825–1839. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little RJ. Regression with missing X's: a review. J Am Stat Assoc. 1992;87:1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.SOLAS software. Saugus, MA: Statistical Solution Ltd.; 2001. Retrieved from http://www.statsol.ie/html/solas/solas_resources.html. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 2006;332:259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heckbert S, Rutter CM, Oliver M, et al. Depression in relation to long-term control of glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids in patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:524–529. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1272-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markowitz S, Gonzalez JS, Wilkinson JL, Safren SA. Treating depression in diabetes: emerging findings. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Nuyen J, Stoop C, et al. Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, et al. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1155–1159. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]