Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the evidence on the association between migraine and mortality.

Methods

Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies investigating the association between any migraine (all forms of migraine collectively) or migraine subtypes (e.g. migraine with aura) and mortality published until March 2011.

Results

We identified ten cohort studies. Studies differed regarding the types of mortality investigated and only four presented aura-stratified results, limiting pooled analyses for migraine subtypes and cause-specific mortality. For any migraine pooled analysis does not suggest an association with all-cause (five studies; pooled relative risk [RR]=0.90, 95%CI 0.71–1.16), cardiovascular (CVD; six studies; pooled RR=1.09, 95%CI 0.89–1.32), or coronary heart disease mortality (CHD; three studies; pooled RR=0.95, 95%CI 0.57–1.60). Heterogeneity among studies is moderate to high. Two studies each suggest that migraine with aura increases risk for CVD and CHD mortality.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis does not suggest that any migraine is associated with mortality from all-causes, CVD, or CHD. However, there is heterogeneity among studies and suggestion that migraine with aura increases CVD and CHD mortality. Given the high migraine prevalence a definitive answer to the question if migraine or a subtype alters risk for mortality is of high public health importance; hence, further studies are needed.

Keywords: migraine, migraine aura, mortality, cardiovascular disease, meta-analysis

Introduction

Migraine is a common neurological disorder affecting about 18% of the female and 6% of the male population (1). Clinically it presents with recurrent headache attacks, associated symptoms of vegetative disturbance, and hypersensitivity of various functional systems of the nervous system (2, 3). Further, about one-third of migraineurs experience transient neurological symptoms mostly involving the visual system prior to or during the migraine attack, which are known as migraine aura (3).

Migraine carries a tremendous individual, societal, and economic burden (4, 5) and the World Health Organization has listed migraine among the twenty most disabling global conditions (http://www.who.int/whr/2001/chapter2/en/index3.html). In addition, research has established that migraine, in particular migraine with aura, is associated with a high co-morbidity burden, mostly involving cardiovascular disease (CVD), psychiatric, neurological, and other pain disorders (6).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has summarized the evidence from studies investigating the association between migraine and CVD (7). While migraine, in particular migraine with aura (MA), was associated with a two-fold increased risk for ischemic stroke, there was no overall association between migraine and other CVD outcomes including myocardial infarction and CVD mortality. However, authors of a recent large population-based study from Iceland have reported that MA is an independent risk factor for CVD mortality (8). In addition, analyses from that study found that MA increases the risk for all-cause mortality.

Given the high prevalence of migraine in the population, it would be of enormous public health importance, if an increased mortality risk among migraineurs with aura was also found in other populations and proved to be a general phenomenon of MA. Hence, we sought to summarize the current evidence on the association of migraine with all-cause as well as cause-specific mortality by systematically reviewing the literature and performing a meta-analysis.

Methods

To perform this meta-analysis, we used the guidelines published by the MOOSE group for the design, performance, and reporting of meta-analyses of observational studies (9).

Data Sources and searches

Two investigators (M.S., P.M.R.) independently searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Science Citation Index from their inceptions through March 2011 using the terms “migraine disorders” or “migraine” combined with the terms “mortality”, “fatal outcome”, “death”, or “survival”. The “explode” feature was used where applicable and no language restrictions were applied. We also manually searched the reference lists of all primary and review articles. The agreement of the search results was good (κ=0.76), disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Study selection

A priori, we established the following inclusion criteria. First, studies were required to have a case-control or cohort design. Second, the studies must investigate patients with migraine and control subjects without migraine. Third, in their analyses the authors must use an adjusted model or a matching procedure that controls for potential confounding. Fourth, the study must provide effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or enough data to calculate these. Finally, if studies have overlapping cases and/or controls, the most informative study with extractable data meeting all the other inclusion criteria will be included.

To determine which studies to include, two investigators (M.S., T.K.) screened the title and abstracts of all studies identified in the literature search and excluded all studies that did not meet any of the pre-specified criteria. The same investigators then reviewed the full articles of the remaining studies and excluded any studies not meeting our inclusion criteria. Agreement of study selection was excellent (κ=0.85), disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction

Two investigators (M.S., P.M.R.) independently extracted data from the articles and entered them into a customized database. The extracted data included the authors’ names and title of the study, country where the study was performed, year of publication, study design, source population, study size, duration of follow-up, age and gender distribution of participants, criteria used for migraine diagnosis, migraine status including aura, form of mortality investigated (e.g. all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, etc.), and effect estimates with 95% CIs. Agreement for data extraction was excellent (κ=0.97), all disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

We included all studies regardless of their gender and age distributions and criteria for migraine diagnosis. We performed an overall analysis of the association between any migraine (i.e. all forms of migraine taken collectively as presented in each study) and all-cause mortality. We also investigated other mortality outcomes if investigated in at least two independent studies (i.e. CVD mortality, coronary heart disease [CHD] mortality). For each of the outcomes we also attempted to perform analyses separately for migraine with aura and migraine without aura [MO] as well as for women and men.

We made the assumption that the odds ratios from case-control studies approximate the hazard ratios and rate ratios from cohort studies. For each study we weighted the log of the effect estimate by the inverse of its variance to obtain pooled relative risk (RR) estimates. We decided to run random effect models, since they include assumptions about potential differences between studies as opposed to fixed effects models. We performed the DerSimonian and Laird Q test for heterogeneity and calculated the I2 statistic (10). The I2 statistic gives an estimate of the percentage of total variation across studies, that is likely due to true differences as opposed to chance. Thus, a high percentage indicates high heterogeneity and a low percentage indicate low heterogeneity. The following cutoff points may serve as guideline: 25% low heterogeneity, 50% medium, 75% high (10). To visually examine the impact of individual studies on the overall homogeneity of the test statistic, we constructed Galbraith plots (11). Finally, to test for small study effects, e.g. publication bias, we used statistical methods described by Begg and Mazumdar (12) and Egger (13). Small study effects denote the tendency for smaller studies in meta-analysis to show larger treatment effects. P-values<0.05 from formal tests provide indication for small study effects.

A two-tailed P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant and all analyses were carried out using STATA v.10.1 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

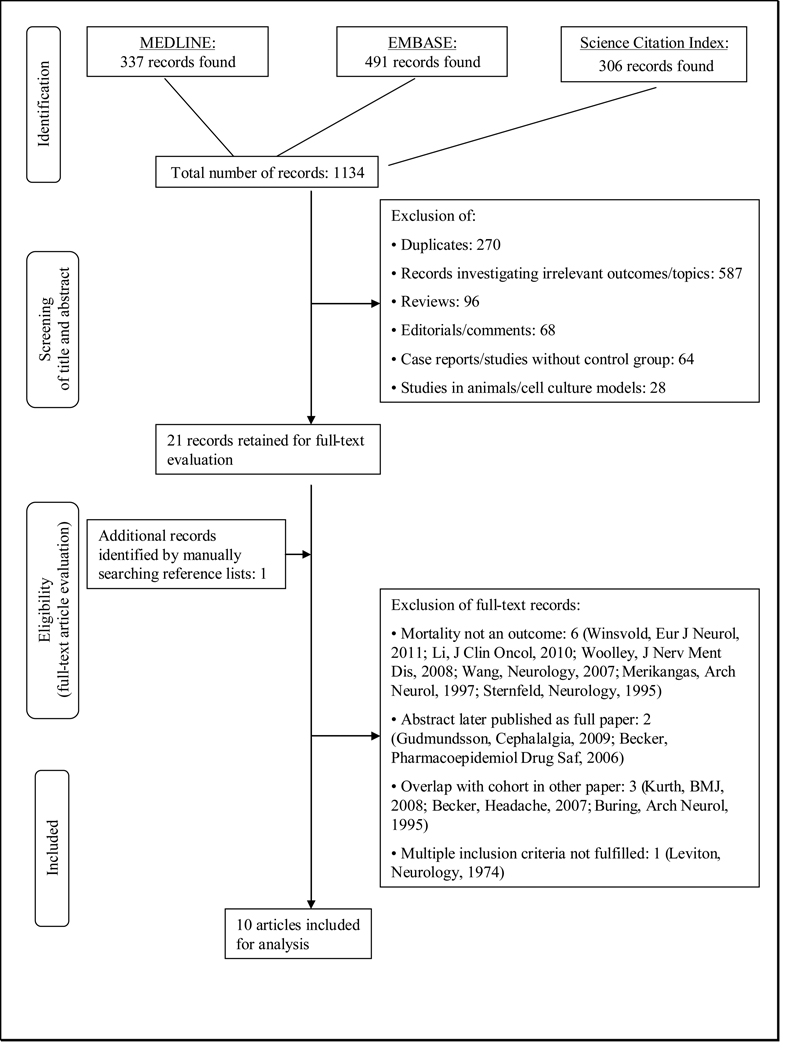

Figure 1 summarizes the selection process of studies for inclusion in this meta-analysis. The electronic search identified 1134 references. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and excluding records not meeting our inclusion criteria, we were left with 21 records. Searching the reference lists of these, we identified one additional record. We evaluated these 22 records as full text references and excluded six because mortality was not an outcome (14–19), two because they were abstracts and later published as full papers (20, 21), three because cohorts overlapped with those in other records (22–24), and one because multiple inclusion criteria were not fulfilled (25). We were finally left with ten articles for our meta-analysis (8, 26–34).

Figure 1.

Process of selecting studies

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the ten included studies are summarized in Table 1. All studies were cohort studies. In five studies migraine was diagnosed according to strict or modified International Headache Society (IHS) criteria (8, 27, 30–32), other studies used criteria applied before the introduction of the IHS criteria (34), questionnaire-based self-report (26, 27, 29), or physician-/ICD-based coding in databases from health care providers (28, 33). All studies reported on any migraine (8, 26–34) while four additionally investigated migraine with and without aura separately (8, 30–32). Five studies investigated all-cause mortality (8, 26, 28, 33, 34), six CVD mortality (8, 26, 28–30, 33), three CHD mortality (8, 27, 32), and one fatal hemorrhagic stroke (31).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort studies investigating the association between migraine and mortality

| Author, year | Country | Source population |

Follow-up, years | Study size |

Age, years |

Gender | Migraine diagnosis | Migraine status investigated |

Mortality investigated |

Mortality confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waters 1983 (34) | United Kingdom | population based, south Wales | 12 | 2932 | 20–64 | women | questionnaire based interview (questions on headache characteristics; migrainous headache) | headache with 1 or 2 migrainous features; all headaches | all-cause mortality | Death certificates. |

| Cook 2002 (27) | United States | WHS | 6.1 (average) | 39,795 | ≥45 | women | self-report on questionnaire (modified IHS 1 criteria) | any migraine | CHD mortality | Death certificates, hospital records, or observer impression. |

| PHS | 12.9 (average) | 22,011 | 40–84 | men | self-report on questionnaire (yes/no) | any migraine | CHD mortality | |||

| Hall 2004 (28) | United Kingdom | GPRD | migraineurs: 2.97 controls: 2.78 |

140,814 | any | women and men | GPRD database coding (yes/no) | any migraine | all-cause mortality, CVD mortality | ICD-10 codes from GPRD, medical records, or death certificates. |

| Velentgas 2004 (33) | United States | UnitedHealthCare | 1.36 | 260,822 | any | women and men | database coding for migraine diagnosis or triptan prescription | any migraine | all-cause mortality, CVD mortality | Medical claims data and National Death Index. |

| Kurth 2006 (30) | United States | WHS | 10 (mean) | 27,840 | ≥45 | women | self-report on questionnaire (modified IHS 1 criteria) | any migraine, MA, MO, prior migraine | CVD mortality | Autopsy reports, death certificates, medical records, or information from next of kin. |

| Ahmed 2006 (26) | United States | WISE study | 4.4 (median) | 873 | any | women | self-report on questionnaire (yes/no/unknown) | any migraine | all-cause mortality, CVD mortality | Death certificates. |

| Kurth 2007 (29) | United States | PHS | 15.7 (mean) | 20,084 | 40–84 | men | self-report on questionnaire (yes/no) | any migraine | CVD mortality | Autopsy reports, death certificates, medical records, or information from next of kin. |

| Liew 2007 (32) | Australia | Blue Mountain Eye Study | 6 | 1732 | ≥49 | women and men | face-to-face interview (IHS 2 criteria) | any migraine, MA, MO | CHD mortality | Australian National Death Index. |

| Kurth 2010 (31) | United States | WHS | 13.6 (mean) | 27,860 | ≥45 | women | self-report on questionnaire (modified IHS 1 criteria) | any migraine, MA, MO, prior migraine | fatal hemorrhagic stroke | Autopsy reports, death certificates, hospital records, or information from next of kin. |

| Gudmundsson 2010 (8) | Iceland | Reykjavik study | 25.9 (median) | 18,725 | 33–81 | women and men | questionnaire based interview (questions on headache characteristics; IHS 2 criteria) | any migraine, MA, MO, non-migraine headache | all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, CHD mortality, total fatal stroke, other fatal CVD, non-CVD mortality, cancer mortality, mortality from other condition than CVD or cancer | ICD codes for cause of death from Statistics Island. |

WHS, Women's Health Study; PHS, Physician's Health Study; GPRD, General Practice Research Database; WISE, Women's Ischemia Evaluation Examination; MA, migraine with aura; MO, migraine without aura; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CHD coronary heart disease; IHS, International Headache Society

Individual study results for all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and CHD mortality are summarized in Table 2. Table 3 shows the results from pooled analysis along with measures of heterogeneity and small study effects.

Table 2.

Association between migraine and mortality*

| All-cause mortality |

CVD mortality | CHD mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, year | Gender | Migraine status | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | Comment |

| Waters 1983 (34) | women | headache with 1 or 2 migrainous features | 0.78 (0.57–1.08) | NA | NA | RRs are age-adjusted. Results only given for ages 45–64 (n=1310). Women with headaches are compared to women with no headaches. Women reporting headaches with one or more migrainous features are compared with women with headaches only and no headaches. |

| all headaches | 0.72 (0.52–1.00) | NA | NA | |||

| Cook 2002 (27) | women | any migraine | NA | NA | NA | No fatal cases among migraineurs in women, hence, no effect estimates available. |

| men | any migraine | NA | NA | 0.58 (0.32–1.07) | ||

| Hall 2004 (28) | women and men | any migraine | 0.76 (0.70–0.84) | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | NA | |

| women <50 yrs | any migraine | 0.73 (0.56–0.93) | NA | NA | ||

| women >=50 yrs | any migraine | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | NA | NA | ||

| men <50 yrs | any migraine | 0.81 (0.56–1.17) | NA | NA | ||

| men >=50yrs | any migraine | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | NA | NA | ||

| Velentgas 2004 (33) | women and men | any migraine | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) | 0.60 (0.33–1.09) | NA | |

| Kurth 2006 (30) | women | any migraine | NA | 1.63 (1.07–2.50) | NA | |

| MA | NA | 2.33 (1.21–4.51) | NA | |||

| MO | NA | 1.06 (0.46–2.45) | NA | |||

| prior migraine | NA | 1.65 (0.90–3.01) | NA | |||

| Ahmed 2006 (26) | women | any migraine | 0.96 (0.49–1.99) | 1.16 (0.20–6.7) | NA | |

| Kurth 2007 (29) | men | any migraine | NA | 1.07 (0.80–1.43) | NA | |

| Liew 2007 (32) | women | any migraine | NA | NA | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) | No fatal events among migraineurs in men, hence, no effect estimates available. |

| MA | NA | NA | 2.2 (0.7–6.5) | |||

| MO | NA | NA | 0.3 (0.04–2.6) | |||

| men | any migraine, MA, MO | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Gudmundsson 2010 (8) | women and men | any migraine | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | |

| MA | 1.21 (1.12–1.30) | 1.27 (1.13–1.43) | 1.28 (1.11–1.49) | |||

| MO | 1.02 (0.91–1.16) | 1.10 (0.91–1.34) | 1.05 (0.82–1.37) | |||

| non-migraine headache | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 1.03 (0.94–1.14) | |||

| women | any migraine | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | 1.16 (1.00–1.34) | 1.13 (0.93–1.37) | ||

| MA | 1.21 (1.09–1.33) | 1.18 (1.00–1.40) | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) | |||

| MO | 1.06 (0.92–1.22) | 1.09 (0.85–1.40) | 1.03 (0.73–1.46) | |||

| non-migraine headache | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) | 1.13 (1.01–1.27) | 1.14 (0.98–1.34) | |||

| men | any migraine | 1.16 (1.04–1.29) | 1.35 (1.17–1.57) | 1.36 (1.14–1.62) | ||

| MA | 1.23 (1.09–1.38) | 1.42 (1.20–1.68) | 1.43 (1.18–1.74) | |||

| MO | 0.95 (0.76–1.20) | 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | 1.12 (0.76–1.65) | |||

| non-migraine headache | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 0.96 (0.85–1.10) | |||

only mortality outcomes that were investigated in at least two studies are listed.

Legend: RR, relative risk from multivariable-adjusted models; MA, migraine with aura; MO, migraine without aura; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; NA: data not available

Table 3.

Association between migraine and mortality, heterogeneity, and small study effects

| Migraine | Mortality | No. of studies |

Pooled RR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity | Small study effects p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | df | p-value | I2 in % | Begg’s test | Egger’ s test | ||||

| Any migraine | All-cause mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 26, 28, 33, 34) | 5 | 0.90 (0.71–1.16) | 55.5 | 4 | <0.001 | 92.8 | 1.00 | 0.57 | |

| Women (8, 26, 28, 34) | 5* | 0.88 (0.69–1.12) | 31.0 | 4 | <0.001 | 87.1 | 0.62 | 0.28 | |

| Men (8, 28) | 3* | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | 8.5 | 2 | 0.02 | 76.3 | 0.60 | 0.29 | |

| Any migraine | CVD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 26, 28–30, 33) | 6 | 1.09 (0.89–1.32) | 13.0 | 5 | 0.02 | 61.4 | 0.85 | 0.54 | |

| Women (8, 26, 30) | 3 | 1.23 (1.02–1.48) | 2.2 | 2 | 0.33 | 9.4 | 0.60 | 0.63 | |

| Men (8, 29) | 2 | 1.25 (1.00–1.55) | 2.0 | 1 | 0.16 | 49.0 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| MA | CVD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 30) | 2 | 1.57 (0.89–2.78) | 3.2 | 1 | 0.08 | 68.4 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Women (8, 30) | 2 | 1.54 (0.80–2.94) | 3.9 | 1 | 0.05 | 74.1 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Men (8) | 1 | 1.42 (1.20–1.68) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| MO | CVD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 30) | 2 | 1.10 (0.91–1.33) | 0.0 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.0 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Women (8, 30) | 2 | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.0 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.0 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Men (8) | 1 | 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| Any migraine | CHD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 27, 32) | 3 | 0.95 (0.57–1.60) | 5.6 | 2 | 0.06 | 64.2 | 0.60 | 0.49 | |

| Women (8, 32) | 2 | 1.13 (0.93–1.37) | 0.0 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.0 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Men (8, 27) | 2 | 0.94 (0.41–2.14) | 7.1 | 1 | 0.01 | 85.8 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| MA | CHD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants (8, 32) | 2 | 1.29 (1.12–1.50) | 0.9 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.0 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Women (8, 32) | 2 | 1.26 (0.85–1.86) | 1.2 | 1 | 0.28 | 15.5 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Men (8) | 1 | 1.43 (1.18–1.74) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

| MO | CHD mortality | ||||||||

| All participants(8, 32) | 2 | 0.88 (0.37–2.08) | 1.4 | 1 | 0.24 | 26.7 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Women (8, 32) | 2 | 0.87 (0.38–2.00) | 1.3 | 1 | 0.25 | 23.4 | 0.32 | ---- | |

| Men (8) | 1 | 1.12 (0.76–1.65) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | |

RR, relative risk; MA, migraine with aura; MO, migraine without aura; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CHD, coronary heart disease.

two study populations from (28)

Association between migraine and all-cause mortality

Five studies investigated the association between any migraine and all-cause mortality (Table 2). Effect estimates from two studies, one in women (34) and one in a mixed cohort (28), suggested a reduced risk for all-cause mortality; however, this was statistically not significant. Two studies did not find an association (26, 33). One study reported a 15% significantly increased risk for all-cause mortality (8). In analyses stratified by migraine aura status, this association occurred only for MA, translating in a 21% increased risk for all-cause mortality, but not for MO and non-migraine headaches. Further, the pattern of association was similar among women and men.

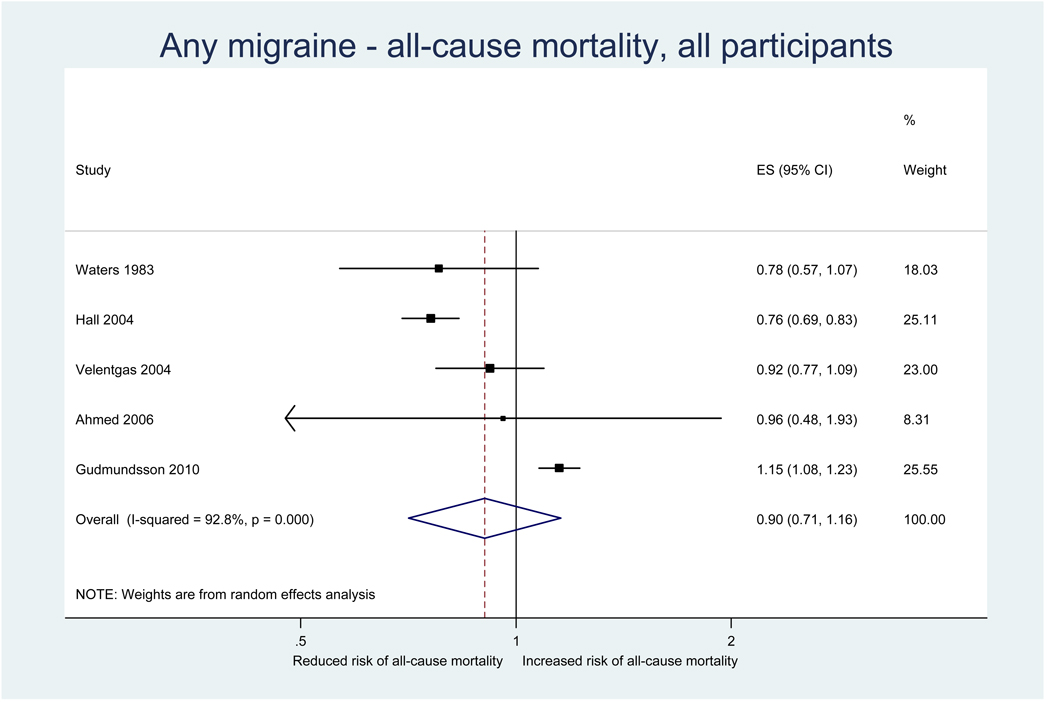

Results from the pooled analysis did not suggested that any migraine alters the risk for all-cause mortality (pooled RR=0.90, 95% CI 0.71–1.16) (Table 3, Figure 2). In separate analyses among women and men the results did not change. Results stratified by migraine aura status were only available from one study (8) suggesting that MA is associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality, but not MO (see previous paragraph, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Relative risks for all-cause mortality among patients with any migraine from the individual studies and from the pooled analysis

Heterogeneity among all studies investigating the association between any migraine and all-cause mortality was high (I2=92.8%) and remained high in gender specific analyses (Table 3). There was no evidence for small study effects in formal investigations with Begg and Egger’s tests.

Association between migraine and CVD mortality

Six studies investigated the association between any migraine and CVD mortality (Table 2). Effect estimates from one study in a mixed population (33) suggested a reduced risk for CVD mortality; however, this was not statistically significant. Three studies, one in a mixed population (28), one in women (26), and one in men (29), did not find an association. Two studies, one among women (30) and one in a mixed population (8), found a significantly increased risk of CVD mortality. In both studies the association only appeared for MA, but not MO. The latter study (8) further stratified the analysis by gender. While the increased risk for CVD mortality limited to MA appeared for women and men, the effect estimates were higher among men than among women.

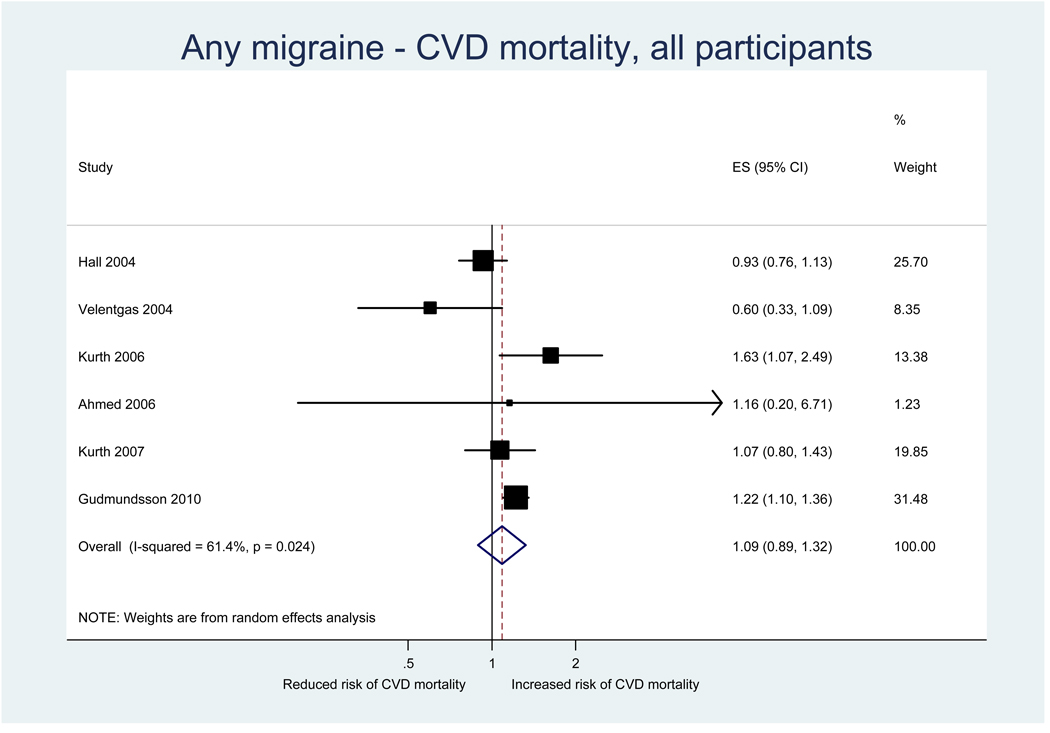

Results from the pooled analysis did not suggested that any migraine alters the risk for CVD mortality (pooled RR=1.09, 95% CI 0.89–1.32) (Table 3, Figure 3). However, gender specific analysis did suggest an increased risk for women (pooled RR=1.23, 95% CI 1.02–1.48) and men (pooled RR=1.25, 95% CI 1.00–1.55).

Figure 3.

Relative risks for CVD mortality among patients with any migraine from the individual studies and from the pooled analysis

Heterogeneity among all studies investigating the association between any migraine and CVD mortality was moderate (I2=61.4%) (Table 3). It remained moderate in analyses among men (I2=49.0%), but was not apparent among women (I2=9.4%).

Effect estimates for CVD mortality among migraineurs with MA suggested an increased, albeit statistically insignificant, risk (pooled RR=1.57, 95% CI 0.89–2.78) (Table 3). However, these were only pooled results from two studies and there was moderate heterogeneity (I2=68.4%). Effect estimates among migraineurs with MO were close to unity and there was no suggestion for heterogeneity.

There was no evidence for small study effects in formal investigations with Begg and Egger’s tests.

Association between migraine and CHD mortality

Three studies investigated the association between any migraine and CHD mortality (Table 2). Effect estimates from one study (27) suggested a reduced risk among men, which was not statistically significant. Another study did not find an association among women for any migraine (32), while analyses stratified by migraine aura status yielded effect estimates suggesting an increased risk for MA and a decreased risk for MO. The third study found a significantly increased risk for CHD mortality (8). This association was only apparent for MA, but not MO and non-migraine headache. The increased risk for CVD mortality limited to MA was apparent for both women and men in gender stratified analyses; the effect estimates were greater among men than women.

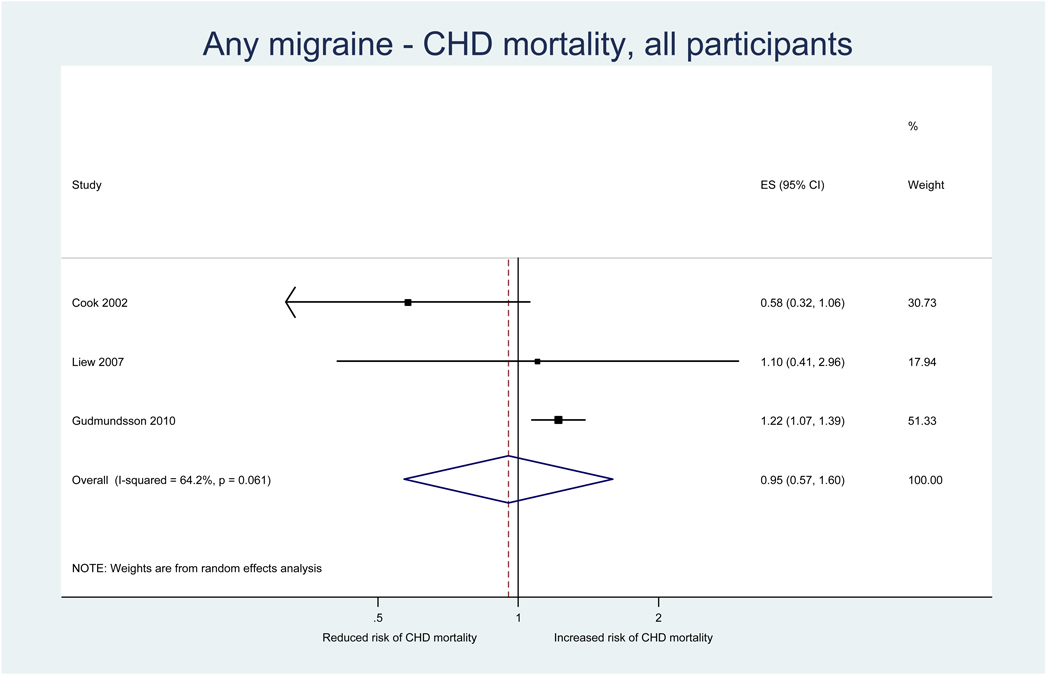

Results from the pooled analysis did not suggest an association between any migraine and CHD mortality (pooled RR=0.95, 95% CI 0.57–1.60) (Table 3, Figure 4). This did not change in separate analyses among women and men.

Figure 4.

Relative risks for CHD mortality among patients with any migraine from individual studies and from the pooled analysis

Heterogeneity among all studies investigating the association between any migraine and CHD mortality was moderate (I2=64.2%) (Table 3). It was high in analyses among men (I2=85.8%), but was not apparent among women (I2=0.0%).

Effect estimates for CHD mortality among migraineurs with MA suggested an increased, statistically significant, risk (pooled RR=1.29, 95% CI 1.12–1.50) (Table 3). There was no suggestion for residual heterogeneity (I2=0.0%). This association was similar for women and men. Effect estimates among migraineurs with MO did not suggest an association with CHD mortality. These results were based on only two studies.

There was no evidence for small study effects in formal investigations with Begg and Egger’s tests.

Association between migraine and other mortality

The risk for other fatal outcomes among migraineurs was only investigated in two studies (Table 1). Authors of one study reported a more than three-fold increased risk for fatal hemorrhagic stroke among women with MA (RR=3.56; 95% CI 1.23–10.31) (31). In the other study, in addition to all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, and CHD mortality as sketched above, other fatal outcomes were investigated (8). The authors report significantly increased risks for total fatal stroke (RR=1.30, 95% CI 1.05–1.61), but not other fatal CVD (not stroke and not CHD; RR=1.12, 95% CI 0.83–1.50). They further report increased risk for mortality unrelated to CVD and cancer (RR=1.19, 95% CI 1.05–1.34), while risk for cancer mortality was not altered (RR=1.02, 95% CI 0.90–1.15). The increased risks reported only occurred among migraineurs with MA (total fatal stroke: RR=1.40, 95% CI 1.10–1.78; mortality unrelated to CVD and cancer: RR=1.25, 95% CI 1.09–1.43), but not among migraineurs with MO.

Sensitivity Analyses

For the association between any migraine and all-cause mortality we first performed sensitivity analysis by excluding the study which was conducted before the introduction of the IHS criteria for migraine and migraine aura (34). The pooled effect estimates were very similar our main analysis (pooled OR=0.93, 95% CI 0.71–1.23).

Further, we used Galbraith plots to identify individual studies that may be potential sources of heterogeneity. We excluded any study that fell outside the margin set by two standard deviations of the z-score and re-ran our analysis.

For the association between any migraine and all-cause mortality, two studies (8, 28) were identified. Exclusion of these studies yielded pooled effect estimates that were very similar to our main analysis (pooled OR=0.89, 95% CI 0.77–1.03), also not suggesting an association. With regard to the association of any migraine and CVD mortality, Galbraith plots did not suggest individual studies as a potential source of heterogeneity.

For all other associations investigated, there were too few studies to perform sensitivity analysis either with Galbraith plots or meta-regression (Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis do not suggest that any migraine alters the risk for all-cause mortality, CVD mortality, or CHD mortality. However, heterogeneity among the studies was medium to high. There is some indication that MA, but not MO, increases the risk for all-cause and CVD and CHD mortality; however, these results stem from small numbers of studies. Hence, there is remaining uncertainty about the true association between migraine, including MA and MO, and all-cause as well as cause-specific mortality.

Beyond the high individual, societal, and economic burden (4, 5), migraine also carries a substantial co-morbidity burden, mostly relating to CVD, psychiatric, neurological, and other pain disorders (6). In particular the association with CVD has been systematically reviewed and analyzed recently (7). The authors found that MA increases the risk for ischemic stroke by two-fold, which was not apparent for MO. There was no overall association between any migraine and myocardial infarction and CVD mortality; however, single studies, which performed analyses stratified by migraine aura status, did suggest that MA increases the risk for myocardial infarction and CVD mortality, while MO did not. In addition, a large population-based study from Iceland recently reported that MA is an independent risk factor for CVD mortality, but also all-cause mortality (8). Results from other studies are in part conflicting (Table 1).

Only a limited number of studies provide data that help to understand how migraine may be linked to mortality. Regarding the association between migraine and CVD, some studies report an association between migraine and vascular risk factors including increased lipid levels, diabetes, elevated blood pressure, history of early onset vascular disease, and higher Framingham Risk Score (35, 36). Hence, presence of these risk factors may confound the association between migraine and CVD/CVD mortality. However, adjustment for these risk factors does not change the associations between MA and CVD/CVD mortality (8, 30), suggesting that they are not strong confounders. Furthermore, some data indicate that women with MA who have the lowest Framingham Risk Score (estimating the 10-year risk of coronary heart disease) have an almost 4-fold increased risk for ischemic stroke, but no altered risk for myocardial infarction compared with non-migraineurs (24). In contrast, women with MA who have the highest Framingham Risk Score had no increased risk for ischemic stroke, but >3-fold increased risk for myocardial infarction. Other reports suggest that specific pathologies of the endothelium/vasculature play a role among migraineurs, which may cause ischemic vascular events in the absence of CVD risk factors. For example, studies have shown an association of migraine with Rose angina (37) and—particularly in young female migraineurs—livedo reticularis (38) and Sneddon’s syndrome (39) as well as functional impairment of the systemic vasculature in migraineurs of recent onset (40). Further, some genetic studies may suggest common susceptibility factors for migraine and CVD mortality. For example, the MTHFR 677C>T and the ACE D/I gene variants are associated with migraine (41), but also play a role in vascular pathology, and have been shown to impact CVD mortality (42, 43). However, no such studies are available with respect to non-CVD related mortality.

Results from our pooled overall analysis do not suggest an association between any migraine and all cause mortality, CVD mortality, and CHD mortality. However, moderate to high heterogeneity among the pooled studies and suggestion for an increased risk in subgroups leaves remaining uncertainties. Hence, when interpreting our results, the following aspects need to be considered.

First, for the association between any migraine and all-cause mortality heterogeneity was high (Table 3); hence, pooling study results may not yield reliable overall estimates and is often discouraged. For our analysis we decided to investigate this overall association and report the results along-side the results according to migraine aura status, gender, and type of mortality for the following reasons. Heterogeneity was only low to moderate among studies investigating CVD and CHD mortality, which provides some indication that the broad outcome all-cause mortality may be a source of heterogeneity. We believe that side-by-side presentation of all results facilitates visual appreciation of this potential source of heterogeneity. This is particularly important because of the limited number of available studies and their data structure not allowing a formal analysis of the sources of heterogeneity with, for example, meta-regression.

Second, migraine is clinically heterogeneous (44) with MA and MO being crude phenotypes, each with an appreciable variability of symptoms, along the wide clinical spectrum of this disorder (45, 46). Even the IHS criteria for migraine and migraine aura status (47, 48), which form the gold-standard of diagnosis, may not capture all this heterogeneity.

Third, studies included for analyses differed with respect to their methods of diagnosing migraine. Some studies used strict or modified IHS criteria (8, 27, 30–32), some used self administered questionnaires (26, 27, 29), and others used databases from health care providers (28, 33). However, the validity of these ascertainment methods has been shown for large population based studies using questionnaire data (30). Further, information in health care provider databases is often based on medical records or claims. In addition, when we excluded the study performed before the introduction of the IHS criteria, our overall results did not change.

Fourth, some studies have reported that the risk for CVD (49, 50) associated with MA is determined by migraine attack frequency. Further, the burden of chronic migraine is disproportionately larger than for episodic forms (51). Hence, while migraine attack frequency or chronic migraine may also impact mortality, no such studies are available.

Fifth, most of the ten studies identified in the literature search investigated only one form of mortality and also differed with respect to the form of mortality investigated (Table 1). In addition, only four studies performed analyses stratified by migraine aura status. Moreover, study populations also differed with respect to their size and gender composition. This further reduced the number of studies that could be grouped for pooled analyses (Table 2 and 3).

Finally, while all studies had a cohort design, time of follow-up varied substantially from just over one year to almost 26 years. If the risk for dying attributable to MA is low it will take many years of follow-up to obtain enough incident fatal cases to calculate stable and reliable effect estimates. Further, if the mortality risk associated with MA only manifests after a minimum number of years, this might not be detected in pooled analysis across the studies. There is some indication for such a time-dependent association, since only the studies with the longest follow-up (8, 30, 31) found increased risks for fatal events among migraineurs with aura.

In light of these limitations attributable to the parent studies our results do not provide sufficient evidence to answer with certainty the question, whether the mortality risk is altered among migraineurs. All-cause mortality may be too gross an outcome to capture risks associated with mortality attributable to specific causes. In addition, data supporting an increased risk of CVD (8, 30) and CHD (8, 32) mortality among migraineurs with aura come from only few studies.

Additional prospective cohort studies are needed to investigate systematically if migraine or a subgroup is associated with mortality from certain causes. These studies need to be large, adequately powered, and have a long follow-up to be able to detect even small to moderate relative risk estimates. Such risk may be considered minor but because of the high prevalence of migraine, the population attributable risk may be high. Any such associations would be of great public health importance. Subsequent studies to investigate the underlying pathophysiology as well as clinical trials to test whether preventive strategies reduce these excess deaths would be called for. Not finding such an association, however, would be equally important as patients could be relieved of a substantial amount of psychological stress and money could be saved by preventing unnecessary studies.

Footnotes

Top 5 references

1. Hall GC, Brown MM, Mo J, MacRae KD. Triptans in migraine: the risks of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and death in practice. Neurology 2004;62:563–568. [G. Hall: gillian_hall@gchall.demon.co.uk]

2. Velentgas P, Cole JA, Mo J, Sikes CR, Walker AM. Severe vascular events in migraine patients. Headache 2004;44:642–651. [A.M. Walker: amwalker@hsph.harvard.edu]

3. Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Logroscino G, Diener HC, Buring JE. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 2006;296:283–291. [T. Kurth: tkurth@rics.bwh.harvard.edu]

4. Liew G, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Migraine and coronary heart disease mortality: a prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia 2007;27:368–371. [J. J. Wang: jiejin_wang@wmi.usyd.edu.au]

5. Gudmundsson LS, Scher AI, Aspelund T, et al. Migraine with aura and risk of cardiovascular and all cause mortality in men and women: prospective cohort study. BMJj 2010;341:c3966. [L. S. Gudmundsson: lsg@hi.is; V. Gudnason: v.gudnason@hjarta.is]

Funding and Support

There was no specific funding for this study.

Full Disclosures for the last 2 years

Dr. Schürks has received an investigator-initiated research grant from the Migraine Research Foundation. He has received honoraria from L.E.K. Consulting for telephone surveys and from the American Academy of Neurology for educational material. P. Rist is funded by a training grant from the National Institute of Aging (AG00158). Dr. Shapiro has served as a consultant for Iroko Pharmaceuticals, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Nautilus Neurosciences, NuPathe, Pfizer, and Zogenix. He has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology and the Headache Cooperative of New England for educational material.

Dr. Kurth has received investigator-initiated research funding from the French National Research Agency, the US National Institutes of Health, Merck, the Migraine Research Foundation, and the Parkinson’s Research Foundation. Further, he is a consultant to World Health Information Science Consultants, LLC; he has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology and Merck for educational lectures and from MAP Pharmaceutical for contributing to a scientific advisory panel.

References

- 1.Lipton RB, Bigal ME. The epidemiology of migraine. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 1:3S–10S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haut SR, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Chronic disorders with episodic manifestations: focus on epilepsy and migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:148–157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet. 2004;363:381–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443–2454. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schürks M, Buse DC, Wang S-J. Comorbidities of headache disorders. In: Martelletti P, Steiner TJ, editors. Handbook of Headache – Practical Management. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2010. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, Buring JE, Lipton RB, Kurth T. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudmundsson LS, Scher AI, Aspelund T, Eliasson JH, Johannsson M, Thorgeirsson G, et al. Migraine with aura and risk of cardiovascular and all cause mortality in men and women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galbraith RF. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat Med. 1988;7:889–894. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li CI, Mathes RW, Bluhm EC, Caan B, Cavanagh MF, Chlebowski RT, et al. Migraine history and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1005–1010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, Fenton BT, Cheng SH, Stolar MJ, Risch N. Association between migraine and stroke in a large-scale epidemiological study of the United States. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:362–368. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sternfeld B, Stang P, Sidney S. Relationship of migraine headaches to experience of chest pain and subsequent risk for myocardial infarction. Neurology. 1995;45:2135–2142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SJ, Juang KD, Fuh JL, Lu SR. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in adolescents with chronic daily headache. Neurology. 2007;68:1468–1473. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260607.90634.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winsvold BS, Hagen K, Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Holmen J, Zwart JA. Headache, migraine and cardiovascular risk factors: the HUNT study. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:504–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woolley SB, Fredman L, Goethe JW, Lincoln AK, Heeren T. Headache Complaints and the Risk of Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:822–828. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31818b4e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker C, Brobert G, Almqvist P, Johansson S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Migraine and the risk of stroke, asthma or death in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15 Suppl. 1:S53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudmundsson LS, Aspelund T, Scher AI, Eliasson JH, Johannsson M, Thorgeirsson G, et al. Migraine, headache and survival in the Reykjavik study. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:59. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker C, Brobert GP, Almqvist PM, Johansson S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Migraine and the risk of stroke, TIA, or death in the UK (CME) Headache. 2007;47:1374–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buring JE, Hebert P, Romero J, Kittross A, Cook N, Manson J, et al. Migraine and subsequent risk of stroke in the Physicians' Health Study. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:129–134. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540260031012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurth T, Schürks M, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, Buring JE. Migraine, vascular risk, and cardiovascular events in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a636. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leviton A, Malvea B, Graham JR. Vascular diseases, mortality, and migraine in the parents of migraine patients. Neurology. 1974;24:669–672. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.7.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed B, Bairey Merz CN, McClure C, Johnson BD, Reis SE, Bittner V, et al. Migraines, angiographic coronary artery disease and cardiovascular outcomes in women. Am J Med. 2006;119:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook NR, Bensenor IM, Lotufo PA, Lee IM, Skerrett PJ, Chown MJ, et al. Migraine and coronary heart disease in women and men. Headache. 2002;42:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall GC, Brown MM, Mo J, MacRae KD. Triptans in migraine: the risks of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and death in practice. Neurology. 2004;62:563–568. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000110312.36809.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Bubes V, Logroscino G, Diener HC, Buring JE. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:795–801. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, Logroscino G, Diener HC, Buring JE. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2006;296:283–291. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurth T, Kase CS, Schürks M, Tzourio C, Buring JE. Migraine and the risk of haemorrhagic stroke in women: a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liew G, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Migraine and coronary heart disease mortality: a prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:368–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velentgas P, Cole JA, Mo J, Sikes CR, Walker AM. Severe vascular events in migraine patients. Headache. 2004;44:642–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waters WE, Campbell MJ, Elwood PC. Migraine, headache, and survival in women. BMJ. 1983;287:1442–1443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6403.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bigal ME, Kurth T, Santanello N, Buse D, Golden W, Robbins M, Lipton RB. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Neurology. 2010;74:628–635. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d0cc8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scher AI, Terwindt GM, Picavet HS, Verschuren WM, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ. Cardiovascular risk factors and migraine: the GEM population-based study. Neurology. 2005;64:614–620. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151857.43225.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose KM, Carson AP, Sanford CP, Stang PE, Brown CA, Folsom AR, Szklo M. Migraine and other headaches: associations with Rose angina and coronary heart disease. Neurology. 2004;63:2233–2239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147289.50605.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tietjen GE, Gottwald L, Al-Qasmi MM, Gunda P, Khuder SA. Migraine is associated with livedo reticularis: a prospective study. Headache. 2002;42:263–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tietjen GE, Al-Qasmi MM, Gunda P, Herial NA. Sneddon's syndrome: another migraine-stroke association? Cephalalgia. 2006;26:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanmolkot FH, Van Bortel LM, de Hoon J. Altered arterial function in migraine of recent onset. Neurology. 2007;68:1563–1570. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260964.28393.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schürks M, Rist PM, Kurth T. MTHFR 677C>T and ACE D/I polymorphisms in migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache. 2010;50:588–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalina A, Czeizel AE. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism (C677T) is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in Hungary. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:333–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Schut AF, Arias Vasquez A, Bertoli-Avella AM, Hofman A, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: the Rotterdam Study. J Med Genet. 2005;42:26–30. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.022756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulder EJ, Van Baal C, Gaist D, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Svensson DA, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: a twin study across six countries. Twin Res. 2003;6:422–431. doi: 10.1375/136905203770326420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Martin NG, Stubbe JH, Nyholt DR. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura are not distinct entities: further evidence from a large Dutch population study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:54–63. doi: 10.1375/183242706776403019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyholt DR, Gillespie NG, Heath AC, Merikangas KR, Duffy DL, Martin NG. Latent class and genetic analysis does not support migraine with aura and migraine without aura as separate entities. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:231–244. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 Suppl 1:9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8 Suppl 7:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacClellan LR, Giles W, Cole J, Wozniak M, Stern B, Mitchell BD, Kittner SJ. Probable migraine with visual aura and risk of ischemic stroke: the stroke prevention in young women study. Stroke. 2007;38:2438–2445. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.488395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurth T, Schürks M, Logroscino G, Buring JE. Migraine frequency and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Neurology. 2009;73:581–588. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2c20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lantéri-Minet M, Duru G, Mudge M, Cottrell S. Quality of life impairment, disability and economic burden associated with chronic daily headache, focusing on chronic migraine with or without medication overuse: A systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0333102411398400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]