Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that α-synuclein overexpression increases the membrane conductance of dopaminergic-like cells. Although α-synuclein is thought to play a central role in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy and diffuse Lewy body disease the mechanism of action is not completely understood. In this study we sought to determine whether multiple factors act together with α-synuclein to engender cell vulnerability through an augmentation of membrane conductance. Here we employed a cell model that mimics dopaminergic neurons coupled with α-synuclein overexpression and oxidative stressors. We demonstrate an enhancement of α-synuclein-induced toxicity in the presence of combined treatment with dopamine and paraquat, two molecules known to incite oxidative stress. In addition we show that combined dopamine and paraquat treatment increases the expression of heme oxygenase-1, an antioxidant response protein. Finally, we demonstrate for the first time that combined treatment of dopaminergic cells with paraquat and dopamine enhances α-synuclein-induced leak channel properties resulting in increased membrane conductance. Importantly, these increases are most robust when both paraquat and dopamine are present suggesting the need for multiple oxidative insults to augment α-synuclein-induced disruption of membrane integrity.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, oxidative stress, pore, leak channel, dopamine, paraquat

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder affecting 1.5 million Americans and 4 million people worldwide (Kempster et al., 2007). Less than 10% of Parkinson’s disease cases derive from a direct genetic cause while the majority of patients present with sporadic/idiopathic disease and lack a clearly defined etiology (Mandel et al., 2005; Klein and Schlossmacher, 2007). However both familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease patients present with similar pathological hallmarks, including a progressive loss of substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) dopamine neurons, loss of dopamine terminals in the putamen, increased microglial activation and the presence of large intracytoplasmic proteinaceous inclusions within the remaining SNpc dopamine neurons called Lewy bodies (Spillantini et al., 1997; Braak et al., 2004; Croisier et al., 2005). Lewy bodies are replete with α-synuclein, a protein that was initially linked to Parkinson’s disease through genetic studies. In fact, both mutations in and overexpression of the gene that encodes for α-synuclein, SNCA, lead to familial forms of Parkinson’s disease (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997; Spillantini et al., 1997; Krüger et al., 1998; Papadimitriou et al., 1999; Singleton et al., 2003; Zarranz et al., 2004; Paleologou et al., 2010). Furthermore, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) link polymorphisms in SCNA with an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, supporting a role for α-synuclein in both familial and sporadic/idiopathic forms of this disease and extending the relevance of this protein to a larger cohort of patients (Satake et al., 2009; Simon-Sanchez et al., 2009; Hamza et al., 2010).

The mechanisms by which α-synuclein incites pathogenesis is multifarious but commonly proposed to be due to a toxic gain of function. Toxicity has been linked to its propensity to misfold and in this paper we explore one potential mechanism for α-synuclein-induced neuronal toxicity in the presence of an oxidative stress environment involving alterations in membrane function leading to increased cellular membrane conductance. The ability of α-synuclein to disrupt membrane integrity and/or form pore-like structures is supported by studies demonstrating the formation of annular α-synuclein in vitro using atomic force and electron microscopy. In addition, we and others have shown increased membrane permeability in α-synuclein-containing synthetic vesicles and cell lines that overexpress this protein (Goldberg and Lansbury, 2000; Volles et al., 2001; Ding et al., 2002; Caughey and Lansbury, 2003; Pountney et al., 2004; Furukawa et al., 2006; Danzer et al., 2007; Kostka et al., 2008; Tsigelny et al., 2008; Auluck et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2010). Increased membrane permeability is likely to disrupt cellular ionic balance and facilitate the misregulation of intracellular calcium levels, subsequently leading to increased oxidative stress. Furthermore, the autonomous pacemaking of substantia nigra dopamine neurons increases the influx of calcium resulting in increased mitochondrial oxidative stress making these neurons more susceptible to toxins (Surmeier et al., 2010a; Surmeier et al., 2010b). This finding is relevant to Parkinson’s disease since oxidative stress accumulates with age, the leading risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (Ames et al., 1993; Bishop et al., 2010). Indeed, evidence for oxidative stress in the form of oxidatively modified proteins, lipids and nucleic acids has been observed in post-mortem Parkinson’s disease brains (Dexter et al., 1989; Dexter et al., 1994; Sian et al., 1994; Alam et al., 1997a; Alam et al., 1997b; Mattson et al., 1999; Lotharius and Brundin, 2002; Beal, 2003; Jenner, 2003; Miller et al., 2009).

A potential source of oxidative free radicals within the nigrostriatal system is extravesicular dopamine, a highly reactive molecule that interacts with and incites α-synuclein misfolding (Graham et al., 1978; Conway et al., 2001; Weingarten and Zhou, 2001; Lotharius and Brundin, 2002; Cappai et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Maguire-Zeiss et al., 2006; Moussa et al., 2008; Outeiro et al., 2009). However since α-synuclein and dopamine are normally found within the nigrostriatal system there is likely another factor that contributes to the pathogenic process in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. In fact, accumulating evidence points to the involvement of multiple insults that cumulatively compromise the nigrostriatal system beyond a limiting threshold resulting in Parkinson’s disease (Maguire-Zeiss and Federoff, 2003; Maguire-Zeiss et al., 2005; Elbaz et al., 2007; Klein and Schlossmacher, 2007; Sulzer, 2007; Migliore and Coppedè, 2009a, b). For instance, epidemiological evidence establishes pesticide exposure as one risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (Barbeau et al., 1985; Hubble et al., 1993; Gorell et al., 1998; Engel et al., 2001; Herishanu et al., 2001; Lai et al., 2002). Specifically, paraquat (1,1’dimethyl-4,4’-bipyridilium dichloride), a herbicide widely used to control weed growth, is associated with Parkinson’s disease (Smith, 1985; Rajput et al., 1987; Liou et al., 1997; Schmuck et al., 2002; Dinis-Oliveira et al., 2006). Paraquat is used experimentally as a redox cycler to increase the formation of reactive oxygen species in the form of superoxide free radicals and paraquat-treated animals display some of the pathological features of Parkinson’s disease such as decreased tyrosine hydroxylase fiber density in the striatum, loss of tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons in substantia nigra, evidence for α-synuclein aggregrates and increased oxidative stress (Brooks et al., 1999; Manning-Bog et al., 2003; Thiruchelvam et al., 2004; McCormack et al., 2005; McCormack et al., 2006; Prasad et al., 2007; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008; Fei et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010).

We previously reported that α-synuclein caused an increase in membrane conductance reminiscent of leak channels (Feng et al., 2010). Here we sought to determine whether Parkinson’s disease relevant oxidative stressors would augment α-synuclein-mediated alterations in membrane conductance and subsequently cell death. In this report, we demonstrate for the first time that combined treatment of dopaminergic cells with paraquat and dopamine enhanced α-synuclein-induced leak channel properties resulting in increased membrane conductance and cell death. In addition these increases are most robust when both paraquat and dopamine are present suggesting the ability of multiple oxidative insults to potentiate α-synuclein’s toxic effects.

Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for western blotting: anti-dopamine transporter (DAT; 1:1000; Novus, Littleton, CO), anti-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-α-synuclein for immunoblotting (Syn; 1:1000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-α-tubulin (1:1000; Abcam), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; 1:1000; Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts), horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000; Chemicon/Millipore), horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2000; Chemicon/Millipore). The following antibodies were used for immunocytochemistry: anti-α-synuclein antibody for immunocytochemistry (Syn; 1:1000; NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA), anti-vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2; 1:200; Chemicon/Millipore), Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:2000; Invitrogen).

Cell Culture

MN9DwtsynIRESgfp (MN9Dsyn) cells were engineered and cultured as previously described (kind gift of Dr. Howard Federoff; (Luo et al., 2007; Su et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2010)). MN9Dsyn is an immortalized dopaminergic-like cell line that harbors an integrated transgene affording doxycycline-regulated (DOX; 2.0 µg/mL media, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) human wildtype α-synuclein (Syn) expression and separately, using an internal ribosome entry site (IRES), green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression. The parental cell line (MN9D) was derived from mouse embryonic mesencephalon fused to a neuroblastoma cell line (kind gift of Dr. A. Heller; (Choi et al., 1991b)).

MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium) Assay

MN9Dsyn cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were grown in 96-well plates (Nunclon™, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) in the absence or presence of DOX to induce Syn and GFP expression. Twenty-four hours after induction, cells were treated with vehicle, dopamine (DA; 100 µM), paraquat (PQ; 50 µM), or both DA and PQ for an additional 24 hours. In experiments using L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanin (L-DOPA) in place of dopamine, cells were treated with vehicle, L-DOPA (100 µM), paraquat (PQ; 50 µM), or both L-DOPA and PQ for 24 hours following Syn induction (DA, PQ and L-DOPA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). Cell viability was quantified using an MTT assay as described by the manufacturer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Each experiment was performed with an N of 8 and repeated at least three times. Data are expressed as mean percentage of cell death with respect to untreated control cells (−DOX) ± SEM.

Western Blot Analysis

MN9Dsyn cells (5 × 106 cells/ 10cm plate; Nunclon™) were grown in the absence or presence of DOX to induce Syn and GFP expression. Twenty-four hours after induction, cells were treated with dopamine (DA; 100µM), paraquat (PQ; 50 µM), or both for 24 hours. Following experimental treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently lysed on ice in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich; cat. No. P2714), phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF; 1 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) and Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) using a hand-held motorized homogenizer. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,300 rpm × 15 minutes at 4°C and cleared supernatants retained. The supernatants were subjected to polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (4–16% SDS-PAGE) followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and western blot analyses as described in the figure legends. Immunoreactive complexes were visualized following Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) treatment and exposure to Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were re-probed with a primary antibody against α-tubulin as a loading control. Quantification of protein levels was performed using the EC3 Imaging System (UVP, LLC.; Upland, CA). For α-synuclein oligomer density measurement, bands above 16kDa were included and total optical density of α-synuclein oligomers from each treatment group was quantified and normalized to α-tubulin density.

Immunocytochemistry

VMAT2 ICC MN9Dsyn cells (4 × 104 cells/well; 24-well plate; Nunclon™) were grown on polyethyleneimine-coated (PEI) glass coverslips (diameter = 12 mm, Deckglaser, Germany) for 48 hours without DOX and subsequently processed for immunocytochemistry. α-Synuclein ICC MN9Dsyn cells were grown on PEI-coated glass coverslips in the absence/presence of DOX (Syn and GFP induction). Twenty-four hours after induction, cells were treated with dopamine (DA), paraquat (PQ), DA and PQ, vehicle or untreated for an additional 24 hours (see figure legends for specific treatment paradigms). Cells were subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose/PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, permeabilized and blocked in TBS/4.5% non-fat dry milk (NFDM)/0.1% Triton-X 100 and incubated with an anti-VMAT2 antibody (VMAT2 ICC; Fig. 1ba) or an anti-α-synuclein antibody (α-synuclein ICC; Fig. 2) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS/4.5% NFDM/0.05% Triton-X 100, cells were further incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (VMAT2 ICC; Fig.1b) or Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (α-synuclein ICC; Fig. 2a). After two additional washes in TBS/4.5% NFDM/0.05% Triton-X 100, nuclei were stained with DAPI (100 nM; 4',6'-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen), cells mounted with mowiol (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and imaged. All fluorescent complexes were visualized using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Images were acquired with a Photometrics Coolsnap-fx (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ) camera using the Scanalytic's IPLab software (Fairfax, VA) and further processed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Each experiment was repeated three times.

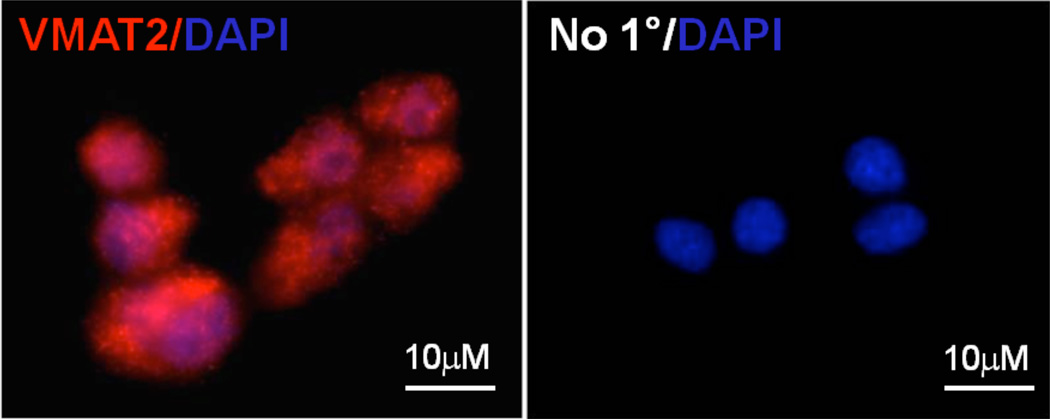

Fig. 1.

Expression of α-synuclein and markers of dopaminergic neurons in MN9Dsyn cells. (a) Representative western blots of MN9Dsyn cell lysates (20 µg / lane) demonstrating the presence of dopaminergic neuron markers, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and dopamine transporter (DAT). (b) Representative image of MN9Dsyn cells immunostained for vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2; red) and subsequently stained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue) (left panel). No primary antibody control counterstained with DAPI (right panel). (c) Representative western blots of MN9Dsyn lysates (20 µg protein / lane) immunoblotted for α-synuclein and reprobed for α-tubulin as a loading control. Administration of doxycycline (+DOX) induces robust α-synuclein overexpression (+DOX) compared to uninduced MN9Dsyn (−DOX).

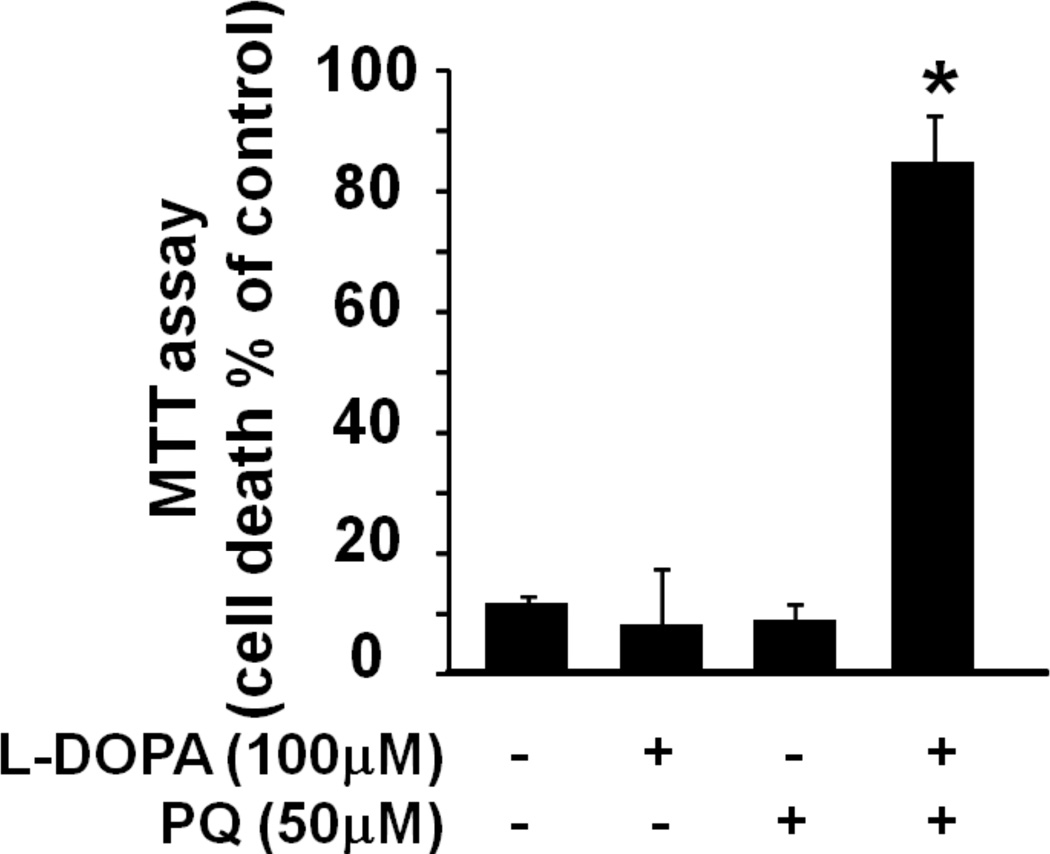

Fig. 2.

Treatment with dopamine and paraquat augments α-synuclein-induced cell death. (a) Representative images of MN9Dsyn cells overexpressing α-synuclein (+DOX/Syn) and treated with vehicle (Syn), dopamine (DA), paraquat (PQ) or both following immunocytochemistry for α-synuclein (red). Membrane localized, nuclear and cytosolic α-synuclein as well as aggregates (white arrows) are present in the α-synuclein overexpressing cells. DAPI (blue) was used to visualize the nuclei. Scale bar = 25 µm. Syn-specific aggregates are more apparent in the higher magnification inset photomicrograph (white box; arrow; scale bar = 10 µm). Cell loss and shrunken / punctate nuclei are evident in Syn-overexpressing cells treated with both DA and PQ (Syn + DA + PQ). (b) MTT assay of MN9Dsyn cells treated with DA (100 µM), PQ (50 µM), or both. Cell death was calculated as the percentage of mitochondrial activity reduction following α-synuclein overexpression (+DOX/Syn) as compared with uninduced (−DOX) controls for the same treatment group (DA, PQ, or both). Values are expressed as percent cell death ± SEM (N = 8 wells/treatment). Each experiment was repeated at least three times. One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post-hoc test, *Significant difference as compared with untreated controls, P < 0.05. Syn overexpression alone resulted in 9% cell death; treatment with DA or PQ resulted in 32.1% [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+DA) *P = 6×10−5] and 4.5% [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+PQ) P = 0.79)] cell death respectively; treatment with both DA and PQ induced 82.2% cell death [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+DA+PQ) **P = 5×10−13; (+DOX+DA) vs. (+DOX+DA+PQ) #P = 5×10−13). (c) MTT assay of MN9Dsyn cells in the presence and absence of DOX treated with L-DOPA (100 µM), PQ (50 µM), or both. Cell death was calculated as the percentage of mitochondrial activity reduction following Syn overexpression (+DOX/Syn) as compared with uninduced (×DOX) controls for the same treatment group (L-DOPA, PQ, or both). One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post-hoc test, *Significant difference as compared with untreated controls, P < 0.05. Treatment with L-DOPA or PQ resulted in 8.2% [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+L-DOPA) *P = 0.98] and 8.8% [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+PQ) P = 0.99)] cell death respectively; treatment with both L-DOPA and PQ induced 84.8% cell death [(+DOX) vs. (+DOX+L-DOPA+PQ) **P = 1.16×10−5). In the absence of Syn overexpression dopamine (100 µM) and paraquat (50 µM) induced 42% and 12.7% cell death respectively (data not shown).

Electrophysiological Analysis/Whole Cell Patch Clamp Recordings

MN9Dsyn cells (4 × 104 cells/well; 24-well plate; Nunclon™) were grown on PEI-coated coverslips in the absence or presence of DOX (induction of Syn and GFP). Twenty-four hours after induction, both induced and uninduced cells were treated with dopamine (DA), paraquat (PQ), DA + PQ or vehicle for an additional 24 hours. MN9Dsyn-containing coverslips (diameter = 12 mm, Deckglaser, Germany) were placed on the stage of a Nikon TM2000 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) and the cells were continuously perfused with an extracellular solution containing 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Hepes, 5 mM glucose, 0.25 mg/l phenol red, 10 µM D-serine and 23.4 mM sucrose pH 7.4 (all reagents obtained from Sigma-Aldrich). Electrodes were pulled on a vertical pipette puller to a resistance of 4–6 MΩ from borosilicate glass capillaries (Wiretrol II, Drummond, Broomall, PA) and filled with intracellular recording solution containing 145 mM CsCl, 10 mM Hepes, 5 mM MgATP, 0.2 mM NaGTP and 10 mM 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) pH 7.2. Whole cell voltage clamp recordings were performed at room temperature using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). To measure input resistance, the membrane potential was held at 0 mV and stepped to levels from −45 mV to 45 mV in 5 mV increments. Currents were filtered at 2 kHz with an 8-pole low pass Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA), digitized at 5–10 kHz with Digidata 1322 A data acquisition board and pCLAMP9.2 software (both from Molecular Devices). All data were analyzed with Clampfit 9.2 software (Molecular Devices) and are the average of 9–20 cells/treatment condition from four independent experiments. Statistical analyses for multiple comparisons was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment was performed subsequent to the ANOVA.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses for multiple comparisons was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc test or paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment for observations of Syn and DA/PQ-induced cell death, changes in HO-1 protein levels, as well as electrophysiological analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results were considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Treatment with dopamine and paraquat augments α-synuclein-induced cell death

Pathogenesis of sporadic Parkinson’s disease likely involves multiple factors including genetic vulnerability and environmental insults (Maguire-Zeiss and Federoff, 2003; Maguire-Zeiss et al., 2005; Cicchetti et al., 2009). To investigate how various insults may act in concert to enhance cell vulnerability, we utilized an immortalized dopaminergic cell line that harbors an integrated transgene affording doxycycline (DOX) regulated human wildtype α-synuclein (Syn) expression and using an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) also expresses green fluorescent protein (Choi et al., 1991b; Strathdee et al., 1999; Su et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2010). First we showed that MN9Dsyn cells express the characteristic dopaminergic neuronal markers, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), dopamine transporter (DAT) (Fig.1a) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) (Fig.1b). The dopamine content in the parental cell line (MN9D cells) was previously estimated to be 102.0 ± 2.1 fg/cell (Choi et al., 1991a; Choi et al., 1992). Next we established that the MN9Dsyn cell line overexpresses α-synuclein following DOX treatment (Fig. 1c).

Using this cell line, we previously demonstrated toxicity induced by α-synuclein overexpression (Feng et al., 2010). To determine the effects of multiple insults on α-synuclein-induced cell vulnerability, we treated MN9Dsyn cells with the oxidative stressors, dopamine (DA; 100 µM) and paraquat (PQ; 50 µM). Using immunocytochemistry, we initially determined whether human α-synuclein and subsequent treatment with oxidative stressors caused accumulation of this protein. Consistent with our previous observation, α-synuclein localized to the cell membrane, nucleus and cytosol (Fig. 2a; red; (Feng et al., 2010)). In addition, α-synuclein-positive aggregates (white arrows) were apparent in all treatment groups. There was an obvious decrease in cell number when MN9Dsyn cells were treated with both dopamine and paraquat compared with any other treatment group. We next quantified the effect of these stressors on cell viability by measuring the reduction of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT; Fig. 2b). In order to determine α-synuclein-specific effects, we calculated the cell death of DOX-induced cells as a percentage of the uninduced controls for the same treatment group (dopamine, paraquat, or both). Here we show that α-synuclein overexpression resulted in 9.1% cell death while the addition of dopamine or paraquat treatment resulted in 32.1% and 4.5% cell death, respectively, as compared to uninduced controls (−DOX). Interestingly, combined treatment with dopamine and paraquat enhanced the α-synuclein-induced cell death to 82.2% demonstrating an increase in α-synuclein-induced cell death when the combined oxidative stressors are present (Fig. 2b). To determine whether the dopamine precursor, L-DOPA, could affect similar changes, we included L-DOPA in place of dopamine. In Figure 2c we show a significant increase α-synuclein-induced cell death only when all both L-DOPA and PQ are present (84.8%; Fig. 2c).

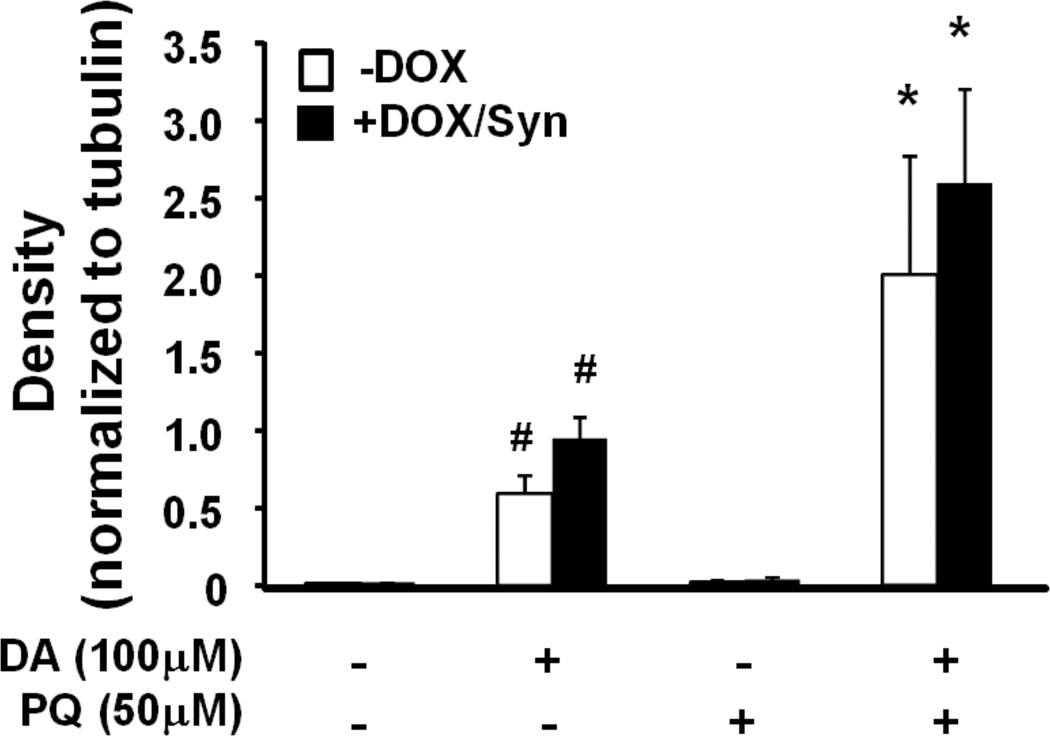

Dopamine and paraquat activate cellular anti-oxidant response mechanisms

Since we observed an augmentation of α-synuclein-induced cell death following treatment with dopamine and paraquat, we next sought to examine the cellular response to these oxidative stressors. An important component of the cellular anti-oxidant response mechanism is the expression of Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor 2)-regulated phase II detoxification enzymes. Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and binds to the anti-oxidant response element facilitating transcription of these genes (Calkins et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009). We chose to interrogate heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protein levels because this Nrf-2-regulated gene has been implicated in Parkinson’s disease (Hung et al., 2008; Schipper et al., 2009; Song et al., 2009). Following treatment of MN9Dsyn cells we observed the most robust increase in HO-1 protein expression following combined treatment with dopamine and paraquat (three-fold increase compared to untreated controls) indicating a cumulative effect of multiple stressors in response to oxidative stress. Neither α-synuclein nor paraquat alone increased HO-1 expression while dopamine had a small but significant effect. These data demonstrate that the combination of paraquat and dopamine enhance the oxidative stress microenvironment of these cells.

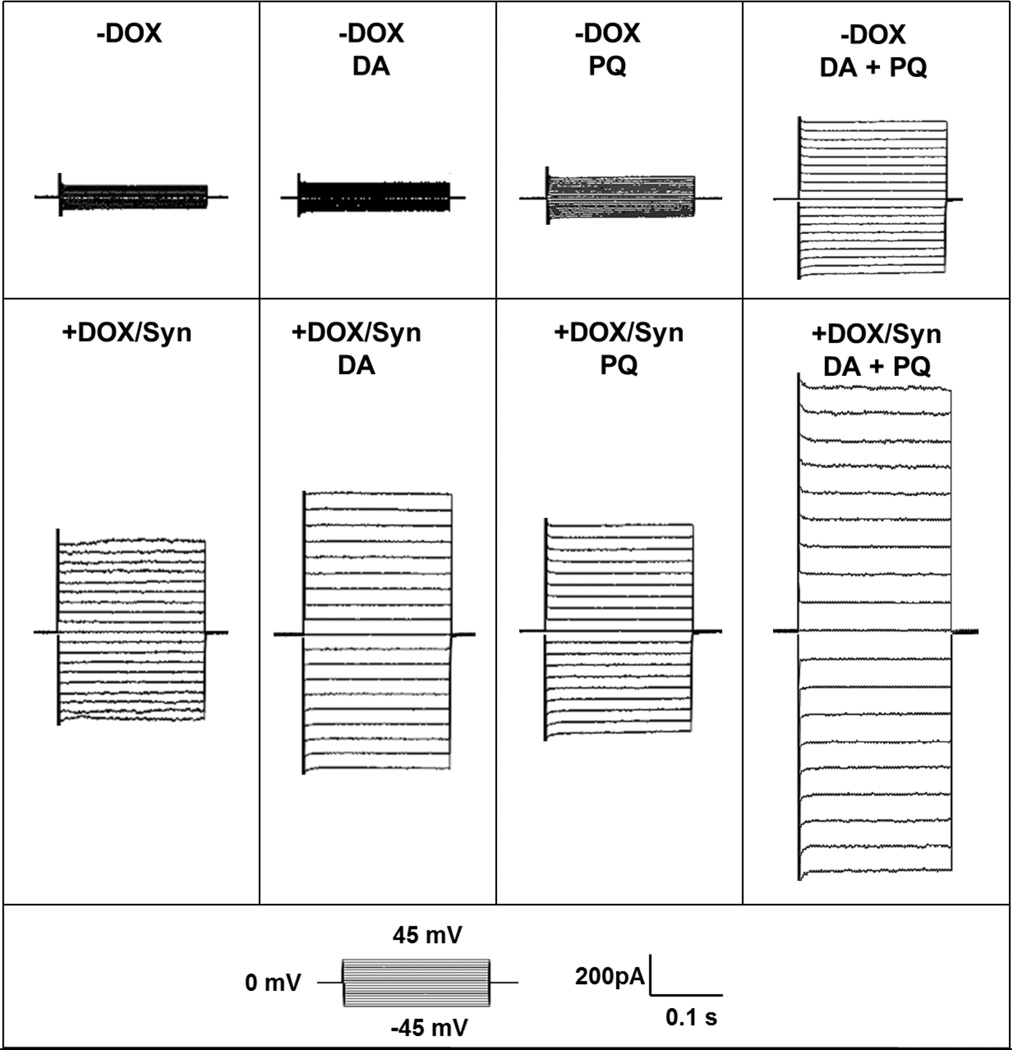

Oxidative stress increases membrane permeability in α-synuclein overexpressing cells

Having established an elevated oxidative stress environment with combined treatment of dopamine and paraquat, we next investigated if the increased levels of oxidative stress resulted in changes in membrane permeability related to α-synuclein overexpression. We performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of induced (+DOX/Syn) and uninduced (−DOX) MN9Dsyn cells treated with dopamine, paraquat or dopamine and paraquat. First, we eliminated potential contributions from voltage-gated potassium or sodium channels by using an intracellular solution containing cesium chloride and a holding potential at 0 mV. Second, to eliminate potential differences due to total cell surface areas, we normalized conductance changes by membrane capacitance. We also normalized the data to control α-synuclein-overexpressing MN9Dsyn cells to reflect the percent changes in membrane conductance resultant of various treatments. Consistent with our previous results, α-synuclein overexpression (+DOX/Syn) alone increased membrane conductance compared with uninduced cells (−DOX; Figure 4A) (Feng et al., 2010). Individual treatment with either dopamine or paraquat did not increase membrane conductance as compared with untreated control (P > 0.05, DA or PQ treated cells vs. untreated control) either in the presence or absence of α-synuclein overexpression. The combined treatment of dopamine and paraquat resulted in elevated membrane permeability in the absence of α-synuclein suggesting that while dopamine or paraquat alone was not sufficient to alter membrane permeability, the combined treatment of both stressors significantly increased membrane conductance indicating compromised membrane integrity (# P < 0.05, significant difference as compared with uninduced cells that were treated with DA, PQ or vehicle). Importantly, the combination of α-synuclein overexpression, dopamine and paraquat led to a more robust and significant increase in membrane conductance when compared with any stressor alone ($ P < 0.05, significant difference as compared with induced cells that were treated with DA, PQ or vehicle). These electrophysiology results are consistent with our data demonstrating increased cell death when MN9Dsyn cells are exposed to this combination of stressors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Oxidative stress increases membrane permeability in α-synuclein overexpressing cells. (a) Representative traces from α-synuclein overexpressing (+DOX/Syn) and uninduced (−DOX) MN9Dsyn cells treated with ± DA ± PQ showing currents elicited by stepping membrane voltage from a holding potential of 0 mV to levels between −45 mV and 45 mV (inset: step voltage protocol). (b) Percent conductance change from α-synuclein overexpressing (+DOX/Syn) and uninduced (−DOX) MN9Dsyn cells treated with ± DA ± PQ. Data were normalized to control α-synuclein-overexpressing MN9Dsyn cells to reflect the percent changes in membrane conductance as a result of various treatments. Values are expressed as percent conductance ± SEM (N = 9–20 cells/treatment group from four independent experiments). α-Synuclein overexpression (+DOX/Syn) increased membrane conductance [*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment, significant difference as compared with uninduced control; (+DOX/Syn) compared with (−DOX)]. Dopamine or paraquat treatment alone did not increase membrane conductance as compared with the untreated control group either in the uninduced (−DOX) or induced (+DOX/Syn) MN9Dsyn cells [statistically insignificant by ANOVA and paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment; (−DOX+DA) and (−DOX+PQ) compared with (−DOX); (+DOX+DA) and (+DOX+PQ) compared with (+DOX)]. Combined treatment of dopamine and paraquat resulted in elevated membrane permeability indicating compromised membrane integrity [# P < 0.05, ANOVA and paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment, (−DOX+DA+PQ) compared with (−DOX)]. Importantly, the combination of α-synuclein overexpression, dopamine and paraquat led to a more robust and significant increase in membrane conductance when compared with any stressor alone [$ P < 0.05, ANOVA and paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment, (+DOX+DA+PQ) compared with (+DOX)].

Since our previous work and that of others demonstrated an alteration in membrane conductance due to the presence of membrane-localized α-synuclein, we next asked whether the elevation of α-synuclein-mediated membrane conductivity in MN9Dsyn cells treated with dopamine and paraquat was due to increases in soluble α-synuclein oligomers (Furukawa et al., 2006; Danzer et al., 2007; Tsigelny et al., 2007; Feng et al., 2010). Protein lysates from induced (+DOX/Syn) and uninduced (−DOX) MN9Dsyn cells treated with dopamine and paraquat were prepared in modified RIPA buffer and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions followed by α-synuclein western blot analysis to analyze soluble oligomers. Monomeric α-synuclein and SDS-stable α-synuclein oligomers (black vertical line) were present following DOX induction (Fig. 5a). We did not observe a significant difference in monomeric or SDS-stable oligomeric α-synuclein density among the induced (+DOX/Syn) MN9Dsyn cells treated with dopamine, paraquat, or both (Fig. 5b). These results in combination with the membrane conductance (Fig. 4) and immunocytochemical (Fig. 2a) data suggest that the combined dopamine and paraquat augmentation in membrane conductivity is not due to increased α-synuclein aggregation.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of α-synuclein protein levels in treated MN9Dsyn cells. (a) MN9Dsyn cells were treated with (+) and without (−) doxcycline (DOX), dopamine (DA) and paraquat (PQ). Protein lysate samples were subjected to 4–16% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for α-synuclein. The same blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed for α-tubulin as a loading control. Representative western blots revealing the presence of monomeric and SDS-resistant α-synuclein (Syn) oligomers (vertical line; N = 3 / treatment; 20 µg protein / lane). (b) α-Synuclein immunoprotein complexes were quantified by densitometric analysis of western blots and values normalized to α-tubulin. Values are expressed as mean band intensity ± SEM from three samples and analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post-hoc test. There was no statistically significant difference in α-synuclein protein levels among the DOX-treated groups.

Discussion

Emerging evidence points to a complex process in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders involving multiple factors (Maguire-Zeiss and Federoff, 2003; Elbaz et al., 2007; Sulzer, 2007; Migliore and Coppedè, 2009a). It is interesting that advancing age is the predominant risk factor for Parkinson’s disease and that oxidative stress increases with age (Beal, 2003; Mariani et al., 2005; Bishop et al., 2010; Hindle, 2010). Our previous work suggests that one cytotoxic role of α-synuclein results from misfolding of this protein into pore-like structures producing leak channel properties and compromised membrane integrity (Feng et al., 2010). In the current study we hypothesized that elevated levels of oxidative stress would contribute to cell vulnerability by increasing the α-synuclein-mediated membrane conductivity changes resulting in cell death (depicted schematically in Fig. 6). To test this hypothesis, we utilized a dopaminergic cell line with doxcycline-inducible α-synuclein overexpression, MN9Dsyn cells, and assessed the effects of oxidative stress, in the form of extracellular exposure to dopamine and paraquat, on α-synuclein-mediated cell vulnerability. Here we report for the first time increased membrane conductivity indicative of compromised membrane integrity, an enhanced antioxidant response and augmentation of cell death related to α-synuclein overexpression following exposure to both dopamine and paraquat. It is interesting that α-synuclein overexpression in combination with exposure to either stressor alone did not significantly enhance the synuclein-mediated changes in membrane integrity supporting the need for multiple stressors.

Fig. 6.

Hypothesized effect of oxidative stress and α-synuclein on membrane integrity. α-Synuclein induces neuronal toxicity by misfolding into pore like structures and increasing membrane conductance (1 & 2). Dopamine and paraquat each contribute to elevated levels of oxidative stress by increasing intracellular levels of ROS (3a & 4). Dopamine auto-oxidizes extracellularly leading to free radical production and consequently compromised membrane integrity (3b). Intracellular oxidative stress also increases membrane leakage through oxidation of the lipid membrane (5; lightning bolt). Importantly, combined treatment of neurons with dopamine and paraquat enhances the α-synuclein-induced effects in part by increasing α-synuclein leak channel conductivity leading to a disruption of ionic imbalance, and eventually cell death (1–5). Cells attempt to compensate for the increased oxidative stress through activation of anti-oxidant response mechanisms including upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; 6-solid line). HO-1 in turn has been shown to inhibit α-synuclein fibrillization (6-dotted line). In our model this anti-oxidant response is not sufficient to inhibit the combined effects of α-synuclein and oxidative stressors.

The initial genetic clue that α-synuclein was involved in the pathogenic mechanism(s) of Parkinson’s disease emerged with the discovery of familial disease caused by point mutations and multiplications of the α-synuclein gene (SNCA) (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997; Krüger et al., 1998; Papadimitriou et al., 1999; Singleton et al., 2003; Zarranz et al., 2004; Paleologou et al., 2010). Although these mutations and multiplications account for a limited number of familial Parkinson’s disease cases, α-synuclein remains at the center of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis in part because it is localized to the hallmark pathological feature of this disorder, the Lewy body, and recent GWAS studies associate SNCA polymorphisms with an increased risk of developing sporadic Parkinson’s disease (Spillantini et al., 1997; Satake et al., 2009; Simon-Sanchez et al., 2009; Hamza et al., 2010). α-Synuclein is ubiquitously expressed in the brain and exists under normal conditions in a random coil structure serving various physiological functions including synaptic maintenance and vesicle recycling (Abeliovich et al., 2000; Murphy et al., 2000; Cabin et al., 2002; Steidl et al., 2003; Fortin et al., 2005; Burre et al., 2010; Darios et al., 2010; Nemani et al., 2010). In the presence of molecular crowding, changes in pH and oxidative stress, α-synuclein misfolds into protofibrils and the more densely packed fibrils which are components of Lewy bodies (Fig. 6 step 1a; (Shtilerman et al., 2002; Uversky et al., 2002b; Caughey and Lansbury, 2003; Fink, 2006)). Protofibrils are generally considered the toxic species, proposed to form annular structures that can function as leak channels (Fig. 6 steps 1b & 2; (Duda et al., 2000; Goldberg and Lansbury, 2000; Uversky et al., 2001a; Lashuel et al., 2002; Uversky et al., 2002b; Caughey and Lansbury, 2003; El-Agnaf et al., 2003; Cookson, 2005; Uversky, 2007; Cookson and van der Brug, 2008)). Since α-synuclein is ubiquitously expressed throughout the brain, we hypothesize that a micro-environment which promotes α-synuclein-mediated membrane conductance changes may facilitate this protein’s toxicity and result in the selective vulnerability associated with this protein (Maroteaux et al., 1988).

The link between oxidative stress and toxicity induced by α-synuclein is especially relevant in the case of Parkinson’s disease which is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and attendant nigrostriatal projections (Davie, 2008; Hawkes et al., 2009; Lees et al., 2009). An important feature of this population of neurons that has been put forth to explain their selective vulnerability is the presence of the neurotransmitter dopamine and the autonomous pacemaker firing of these neurons, both of which contribute to an increased oxidative environment (Greenamyre and Hastings, 2004; Sulzer, 2007; Guzman et al., 2010). Dopamine is relatively stable in the low pH vesicular environment where it is normally securely sequestered (Eisenhofer et al., 2004), however, extravesicular dopamine results in rapid oxidation by monoamine oxidase or iron-mediated catalysis producing free radicals and highly reactive quinones which can react with various cellular components including the plasma membrane inciting cell death (Fig. 6 steps 3a and 3b ; (Maguire-Zeiss et al., 2005; Sulzer, 2007; Mosharov et al., 2009)). Oxidized dopamine has also been shown to stabilize protofibrillar α-synuclein, which is considered the toxic species, possibly by radical coupling or nucleophilic attack (Conway et al., 1998; LaVoie and Hastings, 1999; Conway et al., 2001; LaVoie et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Norris et al., 2005; Bisaglia et al., 2007; Outeiro et al., 2009). Furthermore, both computational modeling and in vitro studies have demonstrated the importance of α-synuclein C-terminal residues including 125YEMPS129 in the noncovalent interactions with the aromatic ring in dopamine which result in inhibition of α-synuclein fibrillization leading to stabilization of the protofibrillar form and these nonspecific hydrophobic interactions are further enhanced by electrostatic interactions with glutamate83 in the NAC region of α-synuclein (Mazzulli et al., 2006; Mazzulli et al., 2007; Herrera et al., 2008). The metabolic product of dopamine, DOPAC, at low concentrations also inhibits α-synuclein fibrillization by noncovalent interactions with the N-terminus of α-synuclein (Zhou et al., 2009). Interestingly, one group demonstrated that α-synuclein-induced toxicity requires the presence of dopamine (Xu et al., 2002).

Despite the purported neurotoxic role of dopamine, the initiation of pathogenesis in most Parkinson’s disease patients is not likely attributable to dopamine dysregulation but instead a complex event involving multiple factors. For example, exposure to environmental toxicants including paraquat has long been established as a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (Smith, 1985; Hubble et al., 1993; Engel et al., 2001; Lai et al., 2002; McCormack et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Dinis-Oliveira et al., 2006; Migliore and Coppedè, 2009a). Paraquat has been shown to enter the CNS via the neutral amino acid transporter, System L, and affect mitochondrial function (McCormack and Di Monte, 2003; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008). NADPH cytochrome reductases and the mitochondrial complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) both reduce paraquat into a cation radical PQ.+ which is re-oxidized by cellular diaphorases back to paraquat initiating a toxic chain of redox cycling resulting in the production of superoxide free radicals (Clejan and Cederbaum, 1989; Dicker and Cederbaum, 1991; Day et al., 1999; Dinis-Oliveira et al., 2006). As a consequence, paraquat has been shown to induce ROS, lipid peroxidation, DNA damage and cytotoxicity in vitro (Fig. 6 steps 4 & 5; (Schmuck et al., 2002; Peng et al., 2004; Dinis-Oliveira et al., 2006; Black et al., 2008; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008)). Likewise, in vivo, rodents treated with paraquat demonstrate an increase in oxidative stress and substantia nigra dopaminergic neuron vulnerability (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000; McCormack et al., 2002; Manning-Bog et al., 2003; McCormack et al., 2005; McCormack et al., 2006; Cicchetti et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010). Other studies have demonstrated the ability of paraquat to increase α-synuclein fibrilization in vitro and aggregation in dopaminergic neurons in vivo (Uversky et al., 2001b; Manning-Bog et al., 2002; Uversky et al., 2002a; Manning-Bog et al., 2003). Interestingly, in some cases increased α-synuclein aggregation in vivo was accompanied by the absence of nigral degeneration and motor behavioral deficits, while others reported a protective role of α-synuclein overexpression against paraquat toxicity through upregulation of Hsp70 (Manning-Bog et al., 2003; Fernagut et al., 2007; Norris et al., 2007). These discrepancies suggest that the experimental model influences the interaction between α-synuclein and paraquat. Therefore, the α-synuclein effects on paraquat-induced toxicity may depend on the transgenic mouse model, cell culture model and/or specific treatment schemes utilized. Because of the multifactorial nature of sporadic PD pathogenesis, a dopaminergic cell line is a useful model that allows us to dissect out components of the complex interactions between genes (α-synuclein) and oxidative insults (dopamine and paraquat). Furthermore, dopamine and paraquat were chosen in our study because of their relevance to the formation of oxidative stress in the nigrostriatal pathway.

First we established that our model, MN9Dsyn cells, express the rate-limiting enzyme for catecholamine synthesis, tyrosine hydroxylase, dopamine transporter and vesicular monoamine transporter 2, which is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the ability of the MN9D parental cells to produce, transport and store dopamine (Choi et al., 1991a; Chen et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2006; Dong et al., 2008). We also demonstrated an enhancement of α-synuclein-induced toxicity in the presence of both dopamine and paraquat. Similar results were observed when we employed the dopamine precursor, L-DOPA. In this model we cannot distinguish between the effects of intracellular and extracellular dopamine or L-DOPA. In both cases we can envision that these extracellularly applied compounds will become oxidatively modified in the media leading to MN9Dsyn membrane disruption. However, treatment of MN9Dsyn cells with dopamine induced the production of the Nrf2-regulated phase II detoxifying enzyme, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) indicating elevated levels of oxidative stress within the cell following exposure to dopamine. Importantly, combined treatment with dopamine and paraquat induced a significant increase in HO-1 expression above the dopamine-mediated increase (Fig. 6 step 6). Consistent with our previous observation, α-synuclein overexpression alone increased the membrane conductance of MN9Dsyn cells compared to non-α-synuclein-overexpressing cells. Here we report for the first time that in the presence of enhanced oxidative stress induced by the combined treatment of dopamine and paraquat an augmentation in membrane conductance in α-synuclein-overexpressing MN9Dsyn cells and elevated leak channel conductivity.

In our MN9Dsyn model, α-synuclein overexpression alone engendered the formation of SDS-stable soluble α-synuclein oligomers but we did not observe a further increase in soluble oligomer levels or cellular aggregrates in the presence of oxidative stress despite a robust augmentation in membrane conductance. We posit that in our experimental paradigm dopamine, paraquat and α-synuclein have a robust combined endpoint effect, enhanced membrane conductance, but this may occur in the absence of enhanced formation of soluble α-synuclein structures. We envision that extracellular dopamine acts by oxidatively modifying membrane components. It is also probable that a portion of the extracellular dopamine enters the MN9Dsyn cells through the dopamine transporter and this cytosolic dopamine provides a separate source of free radicals via autooxidation or enzymatic degradation by monoamine oxidase (Fig. 6 step 3; (Conway et al., 2001; Cappai et al., 2005; Caudle et al., 2008; Outeiro et al., 2009)). Likewise paraquat enhances the formation of free radicals in the form of superoxides also affecting membrane integrity. We know that paraquat exposure results in an elevated state of oxidative stress and compromised mitochondrial energy production via redox cycling targeting the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Fig. 6, steps 4 & 5; (Heller et al., 1984; Day et al., 1999; Macianskiene et al., 2001; Lim et al., 2002; Yumino et al., 2002; McCormack et al., 2005; Cocheme and Murphy, 2008; Pamplona, 2008)). Lastly, α-synuclein is localized to the membrane where it also promotes membrane dysfunction cumulatively leading to enhance membrane conductance (Fig. 6, steps 1 and 2; (Feng et al., 2010)). It is likely that while α-synuclein itself significantly increased membrane conductance, the presence of oxidative stress further compromised a system already challenged by α-synuclein-induced toxicity disrupting membrane integrity beyond the buffering capacity of the system leading to increased cell vulnerability (Fig. 6, steps 1–5). However, we cannot rule out that our methods (western blot analysis of cell lysates and immunocytochemistry) may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect subtle changes in individual α-synuclein conformers which presumably constitute a small percentage of total α-synuclein (Caughey and Lansbury, 2003). In addition, HO-1 has been shown to induce proteasomal degradation of α-synuclein, which could in our model prevent oligomer accumulation (Fig. 6, step 6; (Song et al., 2008; Song et al., 2009)). Notably, in our paradigm we demonstrated a significant upregulation of HO-1 in the presence of oxidative stressors, which could account for the stable levels of SDS-resistant α-synuclein oligomers.

Nevertheless, despite the lack of increased soluble oligomeric α-synuclein, we observed increased oxidative stress, cell death and membrane conductance suggesting that the multiple-hit MN9Dsyn cells have diminished membrane integrity in addition to α-synuclein leak channels. Despite our increasing understanding of Parkinson’s disease, the cause of this debilitating disease remains largely unknown. Various genes and epidemiological factors have been associated with sporadic Parkinson’s disease, however, no insult or risk factor alone is sufficient to initiate the pathogenic process (Cory-Slechta et al., 2005). The multiple hit hypothesis argues that a combination of stressors including genetic vulnerability and environmental insults together compromise the cellular compensatory mechanisms and converge upon substantia nigra dopamine neuronal cell death (Maguire-Zeiss and Federoff, 2003; Carvey et al., 2006; Sulzer, 2007; Mosharov et al., 2009). Indeed, patients are exposed to a variety of insults over their entire lifespan and each pathogenic process is undoubtedly an issue of great complexity. For instance, while chronic paraquat exposure may contribute to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis in some patients, many risk factors may come into play for other patients, for example, age, genetic polymorphisms, rural living, well water drinking, heavy metal exposure or traumatic brain injury (Smith et al., 1992; Hubble et al., 1993; Gorell et al., 1998; Engel et al., 2001; Di Monte et al., 2002; Lai et al., 2002; McCormack et al., 2002; Elbaz et al., 2007; Migliore and Coppedè, 2009a; Satake et al., 2009; Simon-Sanchez et al., 2009; Hamza et al., 2010; Tanner, 2010). In conclusion, in support of the multiple hit hypothesis for Parkinson’s disease our study provides a possible explanation for oxidative stress-induced cell vulnerability in combination with α-synuclein expression, namely enhanced membrane conductance.

Fig. 3.

Dopamine in combination with paraquat increase heme oxygenase-1 expression. (a) Representative western blots illustrating upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protein levels in MN9Dsyn cells (± DOX) treated with dopamine (DA), and dopamine plus paraquat (PQ). Samples (20 µg protein / lane) were immunoblotted for HO-1. The same blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed for α-tubulin as a loading control. (b) HO-1 immunoprotein complexes were quantified by densitometric analysis of western blots and values normalized to α-tubulin. Values are expressed as mean band intensity ± SEM from six samples/treatment. One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD post-hoc test, *significant difference as compared with untreated controls, P < 0.05. Only cells treated with both DA and PQ demonstrated a significant increase in HO-1 protein levels. [ANOVA, *significance as compared to non-treated control: (+DA+PQ) P = 0.006, (+DOX+DA+PQ) P = 0.00017]. HO-1 protein levels were increased to a lesser extent in cells treated with DA alone as compared to non-treated control (statistically insignificant by ANOVA with Tukey HSD post-hoc test; #P < 0.05 significant by paired t-test with Bonferroni adjustment).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Stefano Vicini for his generous help with electrophysiology and Dr. Howard Federoff for the MN9Dsyn cells. This work was supported by NIEHS (R01ES014470; KMZ).

References

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Fariñas I, Choi-Lundberg D, Ho W-H, Castillo PE, Shinsky N, Verdugo JMG, Armanini M, Ryan A, Hynes M, Phillips H, Sulzer D, Rosenthal A. Mice Lacking [alpha]-Synuclein Display Functional Deficits in the Nigrostriatal Dopamine System. Neuron. 2000;25:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam ZI, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Marsden DC, Jenner P, Halliwell B. A Generalised Increase in Protein Carbonyls in the Brain in Parkinson's but Not Incidental Lewy Body Disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997a;69:1326–1329. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam ZI, Jenner A, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Cairns N, Marsden CD, Jenner P, Halliwell B. Oxidative DNA Damage in the Parkinsonian Brain: An Apparent Selective Increase in 8-Hydroxyguanine Levels in Substantia Nigra. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997b;69:1196–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Caraveo G, Lindquist S. α-Synuclein: Membrane Interactions and Toxicity in Parkinson's Disease. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2010;26 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau A, Dallaire L, Buu N, Poirier J, Rucinska E. Comparative behavioral, biochemical and pigmentary effects of MPTP, MPP+ and paraquat in Rana pipiens. Life Sci. 1985;37:1529–1538. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Mitochondria, Oxidative Damage, and Inflammation in Parkinson's Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;991:120–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaglia M, Mammi S, Bubacco L. Kinetic and Structural Analysis of the Early Oxidation Products of Dopamine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:15597–15605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop NA, Lu T, Yankner BA. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature. 2010;464:529–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AT, Gray JP, Shakarjian MP, Laskin DL, Heck DE, Laskin JD. Increased oxidative stress and antioxidant expression in mouse keratinocytes following exposure to paraquat. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2008;231:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell and Tissue Research. 2004;318:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AI, Chadwick CA, Gelbard HA, Cory-Slechta DA, Federoff HJ. Paraquat elicited neurobehavioral syndrome caused by dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain Research. 1999;823:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Sudhof TC. {alpha}-Synuclein Promotes SNARE-Complex Assembly in Vivo and in Vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabin DE, Shimazu K, Murphy D, Cole NB, Gottschalk W, McIlwain KL, Orrison B, Chen A, Ellis CE, Paylor R, Lu B, Nussbaum RL. Synaptic Vesicle Depletion Correlates with Attenuated Synaptic Responses to Prolonged Repetitive Stimulation in Mice Lacking alpha -Synuclein. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8797–8807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08797.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MJ, Johnson DA, Townsend JA, Vargas MR, Dowell JA, Williamson TP, Kraft AD, Lee J-M, Li J, Johnson JA. The Nrf2/ARE Pathway as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2009;11:497–508. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappai R, Leck S-L, Tew DJ, Williamson NA, Smith DP, Galatis D, Sharples RA, Curtain CC, Ali FE, Cherny RA, Culvenor JG, Bottomley SP, Masters CL, Barnham KJ, Hill AF. Dopamine promotes alpha-synuclein aggregation into SDS-resistant soluble oligomers via a distinct folding pathway. FASEB J. 2005;19:1377–1379. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3437fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvey PM, Punati A, Newman MB. Progressive Dopamine Neuron Loss in Parkinson's Disease: The Multiple Hit Hypothesis. Cell Transplantation. 2006;15:239–250. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle WM, Colebrooke RE, Emson PC, Miller GW. Altered vesicular dopamine storage in Parkinson's disease: a premature demise. Trends in Neurosciences. 2008;31:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Lansbury PT. PROTOFIBRILS, PORES, FIBRILS, AND NEURODEGENERATION: Separating the Responsible Protein Aggregates from The Innocent Bystanders*. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2003;26:267–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CXQ, Huang SY, Zhang L, Liu Y-J. Synaptophysin enhances the neuroprotection of VMAT2 in MPP+-induced toxicity in MN9D cells. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;19:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-C, Vargas MR, Pani AK, Smeyne RJ, Johnson DA, Kan YW, Johnson JA. Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: Critical role for the astrocyte. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Won L, Roback J, Wainer B, Heller A. Specific modulation of dopamine expression in neuronal hybrid cells by primary cells from different brain regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8943–8947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HK, Won LA, Kontur PJ, Hammond DN, Fox AP, Wainer BH, Hoffmann PC, Heller A. Immortalization of embryonic mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons by somatic cell fusion. Brain Research. 1991a;552:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90661-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HK, Won LA, Kontur PJ, Hammond DN, Fox AP, Wainer BH, Hoffmann PC, Heller A. Immortalization of embryonic mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons by somatic cell fusion. Brain Res. 1991b;552:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90661-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti F, Drouin-Ouellet J, Gross RE. Environmental toxins and Parkinson's disease: what have we learned from pesticide-induced animal models? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2009;30:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clejan L, Cederbaum AI. Synergistic interactions between nadph-cytochrome P-450 reductase, paraquat, and iron in the generation of active oxygen radicals. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1989;38:1779–1786. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocheme HM, Murphy MP. Complex I Is the Major Site of Mitochondrial Superoxide Production by Paraquat. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:1786–1798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT. Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant [alpha]-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 1998;4:1318–1320. doi: 10.1038/3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Rochet JC, Bieganski RM, Lansbury PT., Jr Kinetic stabilization of the alpha-synuclein protofibril by a dopamine-alpha-synuclein adduct. Science. 2001;294:1346–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1063522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR. THE BIOCHEMISTRY OF PARKINSON'S DISEASE*. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005;74:29–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR, van der Brug M. Cell systems and the toxic mechanism(s) of alpha-synuclein. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta DA, Thiruchelvam M, Barlow BK, Richfield EK. Developmental pesticide models of the Parkinson disease phenotype. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1263–1270. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croisier E, Moran LB, Dexter DT, Pearce RKB, Graeber MB. Microglial inflammation in the parkinsonian substantia nigra: relationship to alpha-synuclein deposition. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Haasen D, Karow AR, Moussaud S, Habeck M, Giese A, Kretzschmar H, Hengerer B, Kostka M. Different species of alpha-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9220–9232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2617-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios F, Ruiperez V, Lopez I, Villanueva J, Gutierrez LM, Davletov B. [alpha]-Synuclein sequesters arachidonic acid to modulate SNARE-mediated exocytosis. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:528–533. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie CA. A review of Parkinson's disease. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:109–127. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BJ, Patel M, Calavetta L, Chang L-Y, Stamler JS. A mechanism of paraquat toxicity involving nitric oxide synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:12760–12765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter DT, Carter CJ, Wells FR, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y, Lees A, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Basal Lipid Peroxidation in Substantia Nigra Is Increased in Parkinson's Disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1989;52:381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter DT, Holley AE, Flitter WD, Slater TF, Wells FR, Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Jenner P, Marsden CD. Increased levels of lipid hydroperoxides in the parkinsonian substantia nigra: An HPLC and ESR study. Movement Disorders. 1994;9:92–97. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte DA, Lavasani M, Manning-Bog AB. Environmental factors in Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23:487–502. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicker E, Cederbaum AI. NADH-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species by microsomes in the presence of iron and redox cycling agents. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1991;42:529–535. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90315-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding TT, Lee S-J, Rochet J-C, Lansbury PT., Jr Annular alpha-synuclein protofibrils are produced when spherical protofibrils are incubated in solution or bound to brain-derived membranes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10209–10217. doi: 10.1021/bi020139h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Remião F, Carmo H, Duarte JA, Navarro AS, Bastos ML, Carvalho F. Paraquat exposure as an etiological factor of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Heien ML, Maxson MM, Ewing AG. Amperometric measurements of catecholamine release from single vesicles in MN9D cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;107:1589–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda JE, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Neuropathology of synuclein aggregates. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2000;61:121–127. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000715)61:2<121::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Catecholamine Metabolism: A Contemporary View with Implications for Physiology and Medicine. Pharmacological Reviews. 2004;56:331–349. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Agnaf OMA, Salem SA, Paleologou KE, Cooper LJ, Fullwood NJ, Gibson MJ, Curran MD, Court JA, Mann DMA, Ikeda S-i, Cookson MR, Hardy J, Allsop D. alpha-Synuclein implicated in Parkinson's disease is present in extracellular biological fluids, including human plasma. FASEB J: 2003 doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0098fje. 03-0098fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz A, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Interaction between genes and environment in neurodegenerative diseases. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2007;330:318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel L, Checkoway H, Keifer M, Seixas N, Longstreth W, Scott K, Hudnell K, Anger W, Camicioli R. Parkinsonism and occupational exposure to pesticides. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:582–589. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.9.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q, McCormack AL, Di Monte DA, Ethell DW. Paraquat Neurotoxicity Is Mediated by a Bak-dependent Mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3357–3364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng LR, Federoff HJ, Vicini S, Maguire-Zeiss KA. α-Synuclein mediates alterations in membrane conductance: a potential role for α-synuclein oligomers in cell vulnerability. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;32:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Hutson CB, Fleming SM, Tetreaut NA, Salcedo J, Masliah E, Chesselet MF. Behavioral and histopathological consequences of paraquat intoxication in mice: Effects of alpha-synuclein over-expression. Synapse. 2007;61:991–1001. doi: 10.1002/syn.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AL. The Aggregation and Fibrillation of α-Synuclein. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2006;39:628–634. doi: 10.1021/ar050073t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin DL, Nemani VM, Voglmaier SM, Anthony MD, Ryan TA, Edwards RH. Neural Activity Controls the Synaptic Accumulation of {alpha}-Synuclein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10913–10921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2922-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Matsuzaki-Kobayashi M, Hasegawa T, Kikuchi A, Sugeno N, Itoyama Y, Wang Y, Yao PJ, Bushlin I, Takeda A. Plasma membrane ion permeability induced by mutant alpha-synuclein contributes to the degeneration of neural cells. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1071–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Lansbury PT., Jr Is there a cause-and-effect relationship between alpha-synuclein fibrillization and Parkinson's disease? Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E115–E119. doi: 10.1038/35017124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorell J, Johnson C, Rybicki B, Peterson E, Richardson R. The risk of Parkinson's disease with exposure to pesticides, farming, well water, and rural living. Neurology. 1998;50:1346–1350. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DG, Tiffany SM, Bell WR, Gutknecht WF. Autoxidation versus Covalent Binding of Quinones as the Mechanism of Toxicity of Dopamine, 6-Hydroxydopamine, and Related Compounds toward C1300 Neuroblastoma Cells in Vitro. Molecular Pharmacology. 1978;14:644–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenamyre JT, Hastings TG. BIOMEDICINE: Parkinson's--Divergent Causes, Convergent Mechanisms. Science. 2004;304:1120–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1098966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, Kondapalli J, Ilijic E, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 2010;468:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature09536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza TH, Zabetian CP, Tenesa A, Laederach A, Montimurro J, Yearout D, Kay DM, Doheny KF, Paschall J, Pugh E, Kusel VI, Collura R, Roberts J, Griffith A, Samii A, Scott WK, Nutt J, Factor SA, Payami H. Common genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:781–785. doi: 10.1038/ng.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CH, Tredici KD, Braak H. Parkinson's Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1170:615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller KB, Poser B, Haest CWM, Deuticke B. Oxidative stress of human erythrocytes by iodate and periodate Reversible formation of aqueous membrane pores due to SH-group oxidation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1984;777:107–116. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herishanu YO, Medvedovski M, Goldsmith JR, Kordysh E. A Case-Control Study of Parkinson's Disease in Urban Population of Southern Israel. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2001;28:144–147. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100052835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera FE, Chesi A, Paleologou KE, Schmid A, Munoz A, Vendruscolo M, Gustincich S, Lashuel HA, Carloni P. Inhibition of α-Synuclein Fibrillization by Dopamine Is Mediated by Interactions with Five C-Terminal Residues and with E83 in the NAC Region. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindle JV. Ageing, neurodegeneration and Parkinson's disease. Age Ageing. 2010;39:156–161. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubble JP, Cao T, Hassanein RES, Neuberger JS, Roller WC. Risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1693. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.9.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung S-Y, Liou H-C, Kang K-H, Wu R-M, Wen C-C, Fu W-M. Overexpression of Heme Oxygenase-1 Protects Dopaminergic Neurons against 1-Methyl-4-Phenylpyridinium-Induced Neurotoxicity. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;74:1564–1575. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Annals of Neurology. 2003;53:S26–S38. doi: 10.1002/ana.10483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Gil SJ, Koh HC. Paraquat induces alternation of the dopamine catabolic pathways and glutathione levels in the substantia nigra of mice. Toxicology Letters. 2009;188:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Gil SJ, Lee JE, Koh HC. Selective vulnerability of the striatal subregions of C57BL/6 mice to paraquat. Toxicology Letters. 2010;195:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempster PA, Hurwitz B, Lees AJ. A new look at James Parkinson's Essay on the Shaking Palsy. Neurology. 2007;69:482–485. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266639.50620.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Choi JH, Chang JW, Kim SW, Hwang O. Immobilization stress causes increases in tetrahydrobiopterin, dopamine, and neuromelanin and oxidative damage in the nigrostriatal system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C, Schlossmacher MG. Parkinson disease, 10 years after its genetic revolution: Multiple clues to a complex disorder. Neurology. 2007;69:2093–2104. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271880.27321.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka M, Hogen T, Danzer KM, Levin J, Habeck M, Wirth A, Wagner R, Glabe CG, Finger S, Heinzelmann U, Garidel P, Duan W, Ross CA, Kretzschmar H, Giese A. Single Particle Characterization of Iron-induced Pore-forming {alpha}-Synuclein Oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10992–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, SKösel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schols L, Riess O. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Nature Genetics. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai BCL, Marion SA, Teschke K, Tsui JKC. Occupational and environmental risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2002;8:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT., Jr Neurodegenerative disease: amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature. 2002;418:291. doi: 10.1038/418291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Hastings TG. Dopamine Quinone Formation and Protein Modification Associated with the Striatal Neurotoxicity of Methamphetamine: Evidence against a Role for Extracellular Dopamine. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1484–1491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Weihofen A, Schlossmacher MG, Selkoe DJ. Dopamine covalently modifies and functionally inactivates parkin. Nat Med. 2005;11:1214–1221. doi: 10.1038/nm1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. The Lancet. 2009;373:2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H-T, Lin D-H, Luo X-Y, Zhang F, Ji L-N, Du H-N, Song G-Q, Hu J, Zhou J-W, Hu H-Y. Inhibition of α-synuclein fibrillization by dopamine analogs via reaction with the amino groups of α-synuclein. FEBS Journal. 2005;272:3661–3672. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C-S, Lee J-C, Kim SD, Chang D-J, Kaang B-K. Hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in cultured Aplysia sensory neurons. Brain Research. 2002;941:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou H, Tsai M, Chen C, Jeng J, Chang Y, Chen S, Chen R. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: a case-control study in Taiwan. Neurology. 1997;48:1583–1588. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Gao H-M, Hong J-S. Parkinson's disease and exposure to infectious agents and pesticides and the occurrence of brain injuries: role of neuroinflammation. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1065–1073. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotharius J, Brundin P. Pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease: dopamine, vesicles and alpha-synuclein. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:932–942. doi: 10.1038/nrn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Henricksen LA, Giuliano RE, Prifti L, Callahan LM, Federoff HJ. VIP is a transcriptional target of Nurr1 in dopaminergic cells. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macianskiene R, Matejovic P, Sipido K, Flameng W, Mubagwa K. Modulation of the Extracellular Divalent Cation-inhibited Non-selective Conductance in Cardiac Cells by Metabolic Inhibition and by Oxidants. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2001;33:1371–1385. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Zeiss KA, Federoff HJ. Convergent Pathobiologic Model of Parkinson's Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;991:152–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Zeiss KA, Short DW, Federoff HJ. Synuclein, dopamine and oxidative stress: co-conspirators in Parkinson's disease? Molecular Brain Research. 2005;134:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Zeiss KA, Wang CI, Yehling E, Sullivan MA, Short DW, Su X, Gouzer G, Henricksen LA, Wuertzer CA, Federoff HJ. Identification of human [alpha]-synuclein specific single chain antibodies. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;349:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel S, Grunblatt E, Riederer P, Amariglio N, Jacob-Hirsch J, Rechavi G, Youdim MBH. Gene Expression Profiling of Sporadic Parkinson's Disease Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta Reveals Impairment of Ubiquitin-Proteasome Subunits, SKP1A, Aldehyde Dehydrogenase, and Chaperone HSC-70. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1053:356–375. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning-Bog AB, McCormack AL, Purisai MG, Bolin LM, Di Monte DA. alpha -Synuclein Overexpression Protects against Paraquat-Induced Neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3095–3099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning-Bog AB, McCormack AL, Li J, Uversky VN, Fink AL, Di Monte DA. The Herbicide Paraquat Causes Up-regulation and Aggregation of α-Synuclein in Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:1641–1644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Mecocci P. Oxidative stress in brain aging, neurodegenerative and vascular diseases: An overview. Journal of Chromatography B. 2005;827:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Pedersen WA, Duan W, Culmsee C, Camandola S. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Perturbed Energy Metabolism and Neuronal Degeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;893:154–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzulli JR, Armakola M, Dumoulin M, Parastatidis I, Ischiropoulos H. Cellular Oligomerization of α-Synuclein Is Determined by the Interaction of Oxidized Catechols with a C-terminal Sequence. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:31621–31630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzulli JR, Mishizen AJ, Giasson BI, Lynch DR, Thomas SA, Nakashima A, Nagatsu T, Ota A, Ischiropoulos H. Cytosolic catechols inhibit alpha-synuclein aggregation and facilitate the formation of intracellular soluble oligomeric intermediates. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10068–10078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0896-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Atienza JG, Johnston LC, Andersen JK, Vu S, Di Monte DA. Role of oxidative stress in paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell degeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93:1030–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Di Monte DA. Effects of l-dopa and other amino acids against paraquat-induced nigrostriatal degeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;85:82–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Atienza JG, Langston JW, Di Monte DA. Decreased susceptibility to oxidative stress underlies the resistance of specific dopaminergic cell populations to paraquat-induced degeneration. Neuroscience. 2006;141:929–937. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Thiruchelvam M, Manning-Bog AB, Thiffault C, Langston JW, Cory-Slechta DA, Di Monte DA. Environmental Risk Factors and Parkinson's Disease: Selective Degeneration of Nigral Dopaminergic Neurons Caused by the Herbicide Paraquat. Neurobiology of Disease. 2002;10:119–127. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore L, Coppedè F. Genetics, environmental factors and the emerging role of epigenetics in neurodegenerative diseases. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2009a;667:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliore L, Coppedè F. Environmental-induced oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2009b;674:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, James-Kracke M, Sun G, Sun A. Oxidative and Inflammatory Pathways in Parkinson's Disease. Neurochemical Research. 2009;34:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosharov EV, Larsen KE, Kanter E, Phillips KA, Wilson K, Schmitz Y, Krantz DE, Kobayashi K, Edwards RH, Sulzer D. Interplay between Cytosolic Dopamine, Calcium, and [alpha]-Synuclein Causes Selective Death of Substantia Nigra Neurons. Neuron. 2009;62:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa CEH, Mahmoodian F, Tomita Y, Sidhu A. Dopamine differentially induces aggregation of A53T mutant and wild type alpha-synuclein: insights into the protein chemistry of Parkinson's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DD, Rueter SM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Synucleins Are Developmentally Expressed, and alpha -Synuclein Regulates the Size of the Presynaptic Vesicular Pool in Primary Hippocampal Neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3214–3220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03214.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemani VM, Lu W, Berge V, Nakamura K, Onoa B, Lee MK, Chaudhry FA, Nicoll RA, Edwards RH. Increased Expression of [alpha]-Synuclein Reduces Neurotransmitter Release by Inhibiting Synaptic Vesicle Reclustering after Endocytosis. Neuron. 2010;65:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris EH, Uryu K, Leight S, Giasson BI, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Pesticide Exposure Exacerbates [alpha]-Synucleinopathy in an A53T Transgenic Mouse Model. The American Journal of Pathology. 2007;170:658–666. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]