Abstract

Rationale

The Gli transcription factors are mediators of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling and have been shown to play critical roles during embryogenesis. Previously, we have demonstrated that the Hh pathway is reactivated by ischemia in adult mammals, and that this pathway can be stimulated for therapeutic benefit; however, the specific roles of the Gli transcription factors during ischemia-induced Hh signaling have not been elucidated.

Objective

To investigate the role of Gli3 in ischemic tissue repair.

Methods and Results

Gli3-haploinsufficient (Gli3+/−) mice and their wild-type littermates were physiologically similar in the absence of ischemia; however, histological assessments of capillary density and echocardiographic measurements of left-ventricular ejection fractions were reduced in Gli3+/− mice compared to wild-type mice after surgically induced myocardial infarction, and fibrosis was increased. Gli3-deficient mice also displayed reduced capillary density after induction of hind-limb ischemia and an impaired angiogenic response to vascular-endothelial growth factor in the corneal angiogenesis model. In endothelial cells, adenovirus-mediated over-expression of Gli3 promoted migration (modified Boyden chamber), siRNA-mediated down-regulation of Gli3 delayed tube formation (Matrigel™), and Western analyses identified increases in Akt phosphorylation, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation, and c-Fos expression; however, promoter-reporter assays indicated that Gli3 over-expression does not modulate Gli-dependent transcription. Furthermore, the induction of endothelial-cell migration by Gli3 was dependent on Akt and ERK1/2 activation.

Conclusions

Collectively, these observations indicate that Gli3 contributes to vessel growth under both ischemic and non-ischemic conditions and provide the first evidence that Gli3 regulates angiogenesis and endothelial-cell activity in adult mammals.

Keywords: angiogenesis, Sonic Hedgehog, endothelial cells, Gli transcription factors, ischemia, myocardial infarction

Introduction

The zinc finger transcription factor Gli3 participates in Hedgehog (Hh)-signal mediation in mammals. It contains both a weak C-terminal transactivation domain and an N-terminal repressor domain.1 The role and expression pattern of Gli3 during development have been widely studied,2, 3 particularly during neural development. The balance between Sonic hedgehog (Shh) and Gli3 expression regulates normal brain patterning: Gli3 promotes differentiation into dorsal cell types, whereas Shh promotes the expression of ventral-cell markers.4, 5 Gli3 and Shh have been shown to regulate limb skeletal development and digit number6, 7 in a similar manner, and Gli3 also appears to be involved, to a lesser extent, in lung8 and kidney9 development and in somite specification.10 Although Gli3 antagonizes many of the effects of Shh,11 it also activates Gli1 transcription in fibroblasts after Shh treatment,12 thereby contributing positively to Hh-signal transduction. Moreover, Gli3 can function as an Shh-independent transcriptional activator during vertebrate limb-digit patterning.13, 14 In humans, mutations in Gli3 have been associated with several diseases, including Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome15 and Pallister-Hall syndrome.16

During the last few years, we have shown that the Hh pathway is reactivated by ischemia in adult cardiovascular tissue17 and that Shh, when administered either as recombinant protein or via gene therapy, enhances the neovascularization of ischemic tissue by promoting both angiogenesis18 and the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs).19, 20 Very recently, we have demonstrated that Gli2 and Gli3 are upregulated in ischemic limb muscle and may participate in tissue repair, including myogenesis and angiogenesis.21 Gli3 is expressed by endothelial cells (ECs), and promotes EC migration and survival in vitro.21 In vivo, administration of an adenovirus encoding Gli3 increased capillary density and promoted superficial limb perfusion in an animal model of hind-limb ischemia (HLI).21 After considering these observations, we hypothesized that Gli3 plays a role in ischemia-induced angiogenesis and performed a series of studies to further characterize the role of Gli3 during angiogenesis and ischemic tissue repair.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C3HeB/FeJ-Mc1rE-so Gli3Xt-J/J mice (Gli3+/− mice) were bred with C3HeB/FeJ mice; both mouse strains were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). In vivo experiments were performed with Gli3+/− mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates. Mice were handled in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Northwestern University.

Blood pressure measurement

Blood pressure measurements were performed in pre-trained, conscious mice via the tail-cuff method (CODA 6 system, Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT, USA).

Myocardial infarction model and assessments

Myocardial infarction (MI) was induced in 10- to 12-week-old Gli3+/− female mice and their WT littermates (8-9 animals/group). Left-ventricular ejection fractions (LVEFs) were measured echocardiographically 7±1, 14±1, and 28±2 days after MI. Fibrosis and capillary density were evaluated in hearts from mice sacrificed on day 28; fibrosis was reported as the ratio of the length of fibrosis to the left-ventricular (LV) circumference. Capillaries were identified by positive staining for CD31. Surgical, echocardiographic, and histological protocols are summarized in the Online Supplement.

HLI model and assessments

HLI was performed as previously described22 in 8-week-old male mice (5 to 9 animals/group). Capillary density and the number of smooth-muscle containing vessels were evaluated in sections of tibialis anterior muscles stained for the expression of CD31 and smooth-muscle α-actin (αSMA). Surgical and histological protocols are summarized in the Online Supplement.

Corneal angiogenesis assay

Pellets containing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were implanted in the corneas of 6- to 8-week-old female mice as previously described.23 Eight days later, mice were injected with 50 μL fluorescien-BS1-Lectin I (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) 15 minutes before sacrifice. Angiogenesis was quantified by analyzing BS1-Lectin I fluorescence as described previously.24 Pellet preparation and the surgical and histological protocols are summarized in the Online Supplement.

Cell maintenance and transfection/transduction

Human umbilical-vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Cambrex Corporation, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) and MS1 cells (CRL-2279; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained and transfected/transduced as described in the Online Supplement; cell assays were performed 48-72 hours after transfection/transduction. The adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase and green-fluorescent protein (GFP) (Ad-LacZ) was kindly provided by Dr A. Rosenzweig,25 the adenovirus encoding human Gli3 (Ad-Gli3) was kindly provided by Dr C.M. Fan,25 and the adenovirus encoding a dominant-negative mutant of Akt (DN-Akt) was kindly provided by Ken Walsh26. Human Gli3 siRNA (small interfering RNA) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., and non-Gli3–silencing GFP siRNA (5′-GGCUACGUCCAGGAGCGCAdTdT-3′) was purchased from Dharmacon, Inc., Lafayette, CO, USA. The Gli-BS-luciferase, mutant-Gli-luciferase, and pcDNA3.1-His-human Gli3 plasmids were kindly provided by Dr H. Sasaki1, 27. Luciferase was assayed with a luciferase-assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as previously described.28 For each sample, luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity to compensate for differences in transfection efficiency. Each condition was assayed in triplicate, and each experiment was performed at least three times.

Western blot

Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 phosphorylation was evaluated by SDS PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) with anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Akt, anti-p42-p44, and anti-phospho-p42-p44 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA).

Quantitative RT-PCR and microarray analyses

Quantitative RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) was performed with RNA isolated from 3×105 cells or from homogenized skeletal or cardiac muscle; RNA microarray analyses were performed with 3 μg total RNA. Analytical protocols are summarized in the Online Supplement, and primer and probe sequences are reported in Supplemental Table 1.

Cell actiivty assays

Tube-formation was evaluated in Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA)-coated plates and migration was evaluated with a modified Boyden's chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) as summarized in the Online Supplement. Migration under each condition was assayed in triplicate, and each experiment was performed at least three times.

Results

Gli3 mRNA expression is impaired in Gli3+/− mice

To verify that Gli3 expression was reduced in Gli3-haploinsufficient (Gli3+/−) mice and, consequently, that Gli3+/− mice were suitable for studying the role of Gli3 in adult animals, we compared Gli3 mRNA expression in WT and Gli3+/− mice. Gli3 mRNA expression was significantly lower (by >50%) in Gli3+/− mice (Supplemental Figure 1A); however, histological examination of skeletal muscle (Supplemental Figure 1B) and heart tissue (Supplemental Figure 1C) harvested from WT and Gli3+/− mice revealed no apparent structural differences. Similarly, physiological assessments found no significant differences between WT and Gli3+/− mice in blood pressure, heart rate, LV volume, or LVEF (Supplemental Figures 1D-G). Thus, Gli3 haploinsufficiency significantly reduced Gli3 expression, but the muscle tissue of Gli3+/− mice appeared normal, and Gli3+/− mice displayed no significant cardiovascular functional anomalies at baseline.

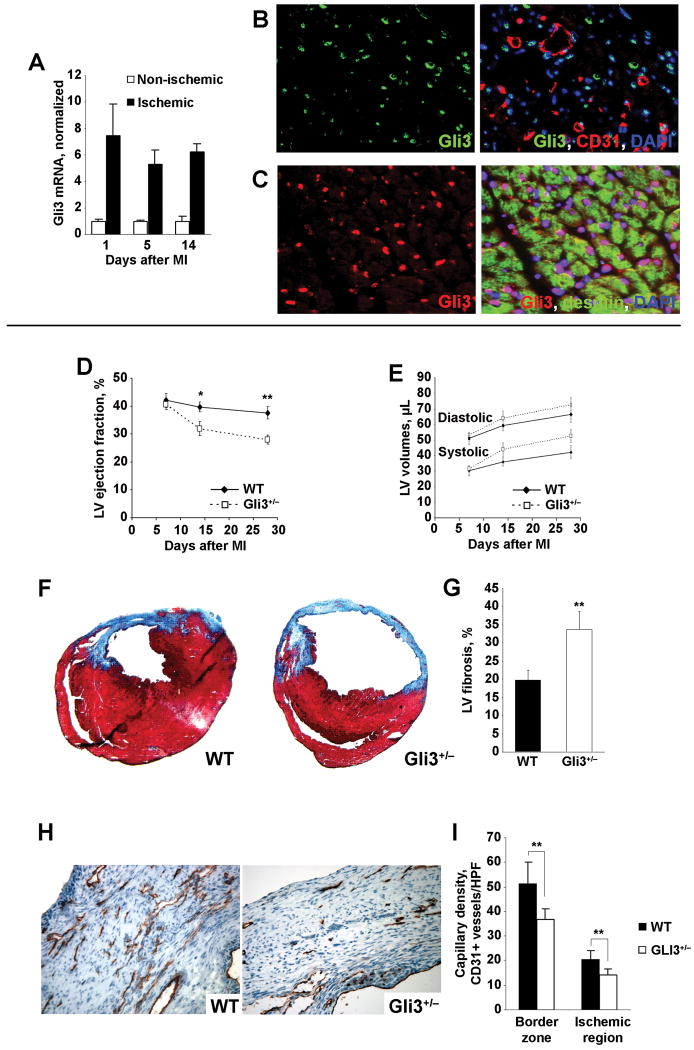

Gli3 contributes to ischemic tissue repair after MI

MI was induced in WT and Gli3+/− mice. In WT mice, Gli3 expression was 5- to 7-fold greater in the ischemic myocardium than in non-ischemic myocardium during the two-week period after MI (Figure 1A). Gli3 was expressed by ECs in the ischemic zone (Figure 1B) and by cardiomyocytes in the border zone of infracted hearts (Figure 1C), but was not expressed by cardiomyocytes in the absence of infarction (Supplemental Figure 2). Echocardiographic measurements of LVEFs indicated that cardiac function was significantly worse in Gli3+/− mice than in WT mice 14 days (Gli3+/−: 31.9±4.49%, WT: 39.7±5.7%; p=0.02) and 28 days (Gli3+/−: 27.9±4.5%, WT: 37.6±7.0%; p=0.004) after MI (Figures 1D-E). In hearts harvested 28 days after MI, fibrosis area was 1.7±5-fold greater (p=0.007) in Gli3+/− mice than in WT mice (Figures 1F-G), and capillary density was 30.14±11.23% (p=0.0015) lower in the ischemic region and 28.29±8.49% (p=0.0044) lower in the ischemic border zone (Figures 1H-I).

Figure 1. Cardiac function, structural integrity, and vascularity were more compromised in Gli3+/− mice than in WT mice after MI.

MI was surgically induced in Gli3+/− mice and their WT littermates. (A) Gli3 mRNA expression was evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression in areas of ischemic and non-ischemic myocardial tissue 1, 5, and 14 days after surgically induced MI. (B) Heart cross-sections were stained with anti-Gli3 antibodies (green) (left panel) or triple stained with anti-Gli3 antibodies (green), anti-CD31 antibodies (red) to identify endothelial cells, and DAPI (blue) to identify nuclei (right panel). (C) Heart cross sections were stained with anti-Gli3 antibodies (red) (left panel) or triple-stained with anti-Gli3 antibodies (red), anti-desmin antibodies (green) to identify cardiac muscle, and DAPI (blue) to identify nuclei (right panel). (D) LV ejection fractions and (E) systolic and diastolic LV volumes were evaluated by echocardiography 7, 14, and 28 days after MI in Gli3+/− (n=8) and WT (n=9) mice. (F) Representative images of Masson trichrome–stained sections from the hearts of WT and Gli3+/− mice harvested 28 days after MI; regions of fibrosis appear blue. (G) Fibrosis area was reported as the ratio of the length of fibrosis to the LV circumference. (H) Representative images of anti-CD31–stained sections from the hearts of WT and Gli3+/− mice harvested 28 days after MI; ECs (i.e., CD31+ cells) appear reddish-brown. (I) Capillary density was quantified as the number of CD31+ vessels per HPF in the ischemic region and in the ischemic border zone. ** p≤0.01; * p≤0.05.

Gli3 contributes to vascular growth in ischemic hind limbs

Our previous experiments21 demonstrated that over-expression of Gli3 promotes neovascularization and perfusion in ischemic hind-limb muscle. To determine the role of endogenous Gli3 expression in response to ischemia, we evaluated the vascularity of ischemic hind-limb muscles from WT and Gli3+/− mice after surgically induced HLI.

Seven and 14 days after HLI, Gli3 mRNA expression in ischemic muscle was approximately 3-fold lower in Gli3+/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 2A), while mRNA expression of Gli2, Gli1, and of the Hh receptor Patched-1 (Ptch1) (Figures 2B-D) was preserved and did not differ significantly between strains. Seven, 14, and 28 days after HLI, capillary density (Figures 2E-F) was significantly lower in tissues harvested from Gli3+/− mice than from WT mice, with the most significant reduction observed on day 7 (Gli3+/−: 9.57±2.24 vessels per high-power field [HPF], WT: 18.56±6.77 vessels/HPF; p=0.0009). The number of vessels that expressed αSMA, a marker for smooth-muscle cells, was also significantly lower (p=0.0009) in Gli3+/− mouse tissues than in tissues from WT mice 14 days after HLI surgery (Figures 2G-H); however, the proportion of vessels that expressed αSMA did not differ significantly (Figure 2I), indicating that the development of vessels containing smooth-muscle cells, which express Gli3,21 may not be disproportionately impaired in Gli3+/− mice.

Figure 2. Angiogenesis is impaired in the ischemic hind limbs of Gli3+/− mice.

HLI was surgically induced in Gli3+/− mice and their WT littermates. Seven and 14 days after HLI, the mRNA expression of (A) Gli3, (B) Gli2, and (C) Gli1, and of the Hh receptor (D) Ptch1 was evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression in muscle harvested from the non-ischemic (NI) and ischemic (I) hind limbs of WT and Gli3+/− mice. (E) Representative images of anti-CD31–stained sections from the ischemic limb muscle of WT and Gli3+/− mice harvested 14 days after HLI; ECs (i.e., CD31+ cells) appear reddish-brown. (F) Capillary density was quantified as the number of CD31+ vessels per HPF; n=8 WT and 9 Gli3+/− mice on day 7, n=7 in each group on day 14, and n=5 WT and 7 Gli3+/− mice on day 28. (G) Representative images of anti-smooth-muscle α-actin (anti-SMA)–stained sections from the ischemic limb muscle of WT and Gli3+/− mice harvested 14 days after HLI; smooth muscle cells (i.e., SMA+ cells) appear reddish-brown. Smooth muscle–containing vessels were quantified as (H) the number of SMA+ vessels per HPF and (I) the proportion of vessels that contained smooth muscle. ***p≤0.001; **p≤0.01.

VEGF-induced angiogenesis is impaired in Gli3+/− mice

The studies described thus far suggest that Gli3 participates in ischemia-induced angiogenesis. To determine whether Gli3 is required for the induction of vessel growth by angiogenic factors, we employed the mouse corneal-angiogenesis model and compared the growth of vessels toward VEGF-containing pellets implanted in the corneas of Gli3+/− and WT mice. VEGF-induced angiogenesis was substantially impaired in Gli3-deficient mice (Figures 3A-B); the expression of Gli3 by ECs in the VEGF-induced vasculature was confirmed via double immunofluorescent staining for Gli3 and for expression of the EC marker von Willebrand factor (vWF) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. VEGF-induced angiogenesis is impaired in Gli3+/− mice.

Pellets containing either PBS or VEGF were implanted in the corneas of Gli3+/− mice and their WT littermates. (A) VEGF-induced angiogenesis was evaluated 8 days later by injecting mice with 50 μL fluorescien-BS1-Lectin I 15 minutes before sacrifice, then viewing the corneas under fluorescence. (B) Angiogenesis was quantified as described previously.24 (C) Corneal cross sections from WT mice implanted with VEGF-containing pellets were stained with anti-Gli3 antibodies (red) and with antibodies to the EC-specific marker vWF (green); nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

Gli3 regulates function and gene expression in ECs

The potential influence of Gli3 on EC function was assessed in vitro. Downregulation of Gli3 delayed tube formation (Figure 4A): 8 hours after seeding on Matrigel™, total tube length was significantly shorter (p=0.008) in HUVECs transfected with Gli3 siRNA (934±976 pixels/HPF) than in cells transfected with GFP siRNA (5261±2008 pixels/HPF). Gli3 over-expression via Ad-Gli3 transduction enhanced HUVEC migration (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Gli3 regulates function and gene expression in ECs.

(A) HUVECs were transfected with Gli3 siRNA or control GFP siRNA, cultured for 48 hours, then seeded on Matrigel™. Tube formation was assessed under a phase-contrast microscope 8 and 24 hours after seeding. (B-G) HUVECs were transduced with adenoviral vectors coding for Gli3 expression (AdGli3) or with control adenoviral vectors coding for LacZ expression (AdLacZ). (B) Forty-eight hours after transduction, 5×104 cells were seeded in the upper chamber of a modified Boyden chamber, and the lower chamber was filled with EBM-2 medium containing 1% fetal-bovine serum. Migration was quantified 8 hours after seeding by calculating the number of cells per HPF that had migrated to the lower chamber. The mRNA expression of (C) CXCL1, (D) CXCL2, (E) Ccl2, (F) IL-8, and (G) PD-ECGF was evaluated via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression. (H) Seven days after surgically induced hind-limb ischemia, PD-ECGF mRNA expression in muscle harvested from the non-ischemic and ischemic hind limbs of WT and Gli3+/− mice was evaluated via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression; n=8 WT mice and 9 Gli3+/− mice. **p≤0.01. (I) HUVECs were co-transfected with 3 plasmids: 1) a plasmid coding for Gli-regulated BS luciferase expression (pGli-BS) or mutant-Gli–regulated BS luciferase expression (pmGli-BS), 2) a plasmid coding for human Gli3 expression (phGli3) or a control pcDNA3 plasmid, and 3) a plasmid coding for LacZ expression. Forty-eight hours after transfection, luciferase activity in cell lysates was assayed and normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

mRNA microanalyses of HUVECs transduced with Ad-Gli3 or Ad-LacZ identified several factors upregulated by Gli3 over-expression, including CXC-chemokine ligand (CXCL) 1 (also known as growth-regulated oncogene α), CXCL2 (growth-regulated oncogene β), CXCL5, CC-motif ligand (Ccl) 2 (monocyte chemotactic protein 1), interleukin (IL) 8 (CXCL8), and colony-stimulating factor 3 (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) (Supplemental Table 2). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses with two different EC lines (HUVECs and MS1 cells) confirmed that Gli3 over-expression upregulated CXCL1, CXCL2, Ccl2, and IL-8 (Figures 4C-F, Supplemental Figures 3A-D). Ad-Gli3 transduction also upregulated the expression of platelet-derived, endothelial-cell growth factor (PD-ECGF) (thymidine phosphorylase) (Figure 4G, Supplemental Figure 3E); notably, PD-ECGF expression was significantly lower (p=0.002) in ischemic limb muscle harvested from Gli3+/− mice than in WT ischemic limb muscle on the seventh day after HLI (Figure 4H).

We also investigated whether Gli3 over-expression influenced Gli-dependent transcription in ECs by evaluating luciferase activity in HUVECs transfected with a plasmid coding for Gli-BS–regulated luciferase expression. Over-expression of Gli3 did not significantly alter luciferase activity (Figure 4I), and similar experiments demonstrated that Gli3 over-expression does not modulate Gli1 or Ptch1 expression in HUVECs (data not shown).

Gli3 activates the Akt pathway and the MAPK-ERK1/2 pathway

Because Hh signaling is known to activate the Akt and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)-ERK1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2) pathways in ECs,29-32 we performed experiments to determine whether these pathways are also activated by Gli3 over-expression.

Western blot analyses indicated that ERK1/2 phosphorylation is higher in ECs transduced with Ad-Gli3 than in Ad-LacZ–transduced HUVECs (Figure 5A), and when Gli3 expression was knocked down by transfection with Gli3 siRNA, the level of phosphorylated ERK1/2 declined both in the presence and absence of VEGF (Figure 5B). Gli3-transduced ECs also expressed markedly higher (25±3-fold) levels of c-Fos, a downstream target of the MAPK-ERK1/2 pathway, and Gli3-induced c-Fos upregulation was significantly lower in the presence of the MAPK-ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (Figure 5C), indicating that ERK1/2 activation contributes to the upregulation of c-Fos expression by Gli3.

Figure 5. Gli3 over-expression in ECs promotes Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

(A) HUVECs were transduced with adenoviral vectors coding for Gli3 expression (AdGli3) or with control adenoviral vectors coding for LacZ expression (AdLacZ), and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (ERK1/2-P) was evaluated 48 hours later by Western blot. (B) HUVECs were transfected with Gli3 siRNA or control GFP siRNA; 48 hours after transfection, cells were treated with or without 50 ng/mL VEGF for 5 minutes, then ERK1/2 phosphorylation was evaluated by Western blot. (C-D) HUVECs were transduced with AdGli3 or AdLacZ; (C) 24 hours after transduction, cells were incubated with 10 μmol/L of the MAPK-ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 or dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle) for 24 hours, then c-Fos mRNA expression was evaluated via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression. (D) Forty-eight hours after transduction, Akt phosphorylation (Akt-P) was evaluated by Western blot. (E) HUVECs were co-transduced with AdLacZ or AdGli3 and AdLacZ or an adenoviral vector coding for a dominant-negative Akt mutant (DN-Akt). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was evaluated 48 hours later by Western blot. (F) HUVECs were transduced with AdGli3 or AdLacZ; 24 hours after transduction, cells were incubated with 10 μmol/L U0126 or dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle) for 24 hours, then Akt phosphorylation was evaluated by Western blot. (G-I). AdLacZ- and AdGli3-transduced HUVECs were incubated with or without 10 μmol/L U0126 for 24 hours or co-transduced with DN-Akt. (G) 5×104 cells were seeded in the upper chamber of a modified Boyden chamber, and the lower chamber was filled with EBM-2 medium containing 1% fetal-bovine serum. Migration was quantified 8 hours after seeding by calculating the number of cells per HPF that had migrated to the lower chamber. (H-I) The mRNA expression of (H) CXCL1 and (I) PD-ECGF was evaluated via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to 18S rRNA expression. ***p≤0.001.

Akt phosphorylation was also higher in Ad-Gli3–transduced HUVECs than in HUVECs transduced with Ad-LacZ (Figure 5D). To determine whether Gli3-induced Akt phosphorylation occurred upstream, downstream, or independently of ERK1/2 activation, phosphorylated Akt and ERK1/2 levels were measured in ECs transduced with Ad-Gli3 and DN-Akt (a dominant-negative mutant of Akt) or in Ad-Gli3–transduced ECs cultured in the presence and absence of U0126. Gli3-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was impaired in ECs co-transduced with DN-Akt (Figure 5E), but Gli3-induced Akt phosphorylation was not affected by the presence of U0126 (Figure 5F), providing evidence that the activation of ERK1/2 by Gli3 occurs downstream of Akt activation.

Gli3-induced EC migration is dependent on both Akt and MAPK-ERK1/2

The role of Akt and ERK1/2 in Gli3-induced EC migration and gene expression was investigated in HUVECs transduced with Ad-Gli3 and DN-Akt or in Ad-Gli3–transduced HUVECs cultured in the presence and absence of U0126. Gli3-induced EC migration declined when cells were co-transduced with DN-Akt or cultured in the presence of U0126 (Figure 5G), indicating that the enhanced migration associated with Gli3 over-expression is dependent on both Akt and MAPK-ERK1/2 activation. DN-Akt co-transduction, but not U0126 exposure, inhibited Gli3-induced expression of CXCL1 (Figure 5H), CXCL2, IL-8, and Ccl2 (Supplemental Figures 4A-C), and CXCL1 expression was also impaired in Ad-Gli3/DN-Akt–co-transduced cells cultured with U0126 (Supplemental Figure 4D), which suggests that Akt, but not ERK1/2, mediates the upregulation of these genes by Gli3. In contrast, PD-ECGF expression in Ad-Gli3–transduced HUVECs was not significantly impaired by DN-Akt co-transduction or by the presence of U0126 (Figure 5I), suggesting that Gli3-induced PD-ECGF expression occurs through an Akt- and ERK-independent mechanism.

Discussion

Very recently, we have shown that Gli3, a transcription factor targeted by Shh during Hh signaling, is strongly upregulated in the ischemic tissue of adult mammals and may have a favorable effect on myogenesis and angiogenesis after an ischemic insult.21 The findings reported here confirm our previous results and are the first to indicate that endogenous Gli3 expression contributes to post-natal angiogenesis. Our in vivo experiments demonstrate that Gli3 haploinsufficiency impairs angiogenesis in both the MI and HLI models and in response to VEGF stimulation, and the impairment in angiogenesis worsened functional outcomes in ischemic animals. Collectively, our observations strongly suggest that Gli3 has an important role during angiogenesis in adult mammals and that Gli3 upregulation is required for normal neovascularization during ischemic tissue repair.

Our previous work demonstrated that Gli3 is expressed in the ECs of ischemic skeletal muscle.21 The current studies extended our earlier findings by identifying Gli3 expression in cardiac ECs after MI, and we also showed that in vitro Gli3 expression regulates EC migration and tube formation. Other reports have identified similarities between the mechanisms involved in angiogenesis and axonal guidance,33-35 which is also dependent on Gli3, and may lead to speculation about whether the regulation of EC activity by Gli3 could be considered analogous to the Gli3-dependent migration of olfactory neurons.36, 37

Gli3 over-expression strongly upregulated the expression of several pro-angiogenic factors in ECs, including IL8 and the CXCR2 ligands CXCL1 and CXCL2.38 IL-8 promotes EC migration and tube formation,39 whereas CXCR2 ligands have been associated with the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells40 and with EPC recruitment,41, 42 both of which contribute to ischemia-induced vascular regeneration. Gli3 over-expression in ECs also upregulated the expression of PD-ECGF, a strong pro-angiogenic factor that has been shown to promote neovascularization in MI43 and HLI44 models; furthermore, PD-ECGF expression in ischemic skeletal muscle was significantly lower in Gli3+/− mice than in WT mice. Thus, the impaired angiogenesis observed in Gli3+/− mice may evolve through a variety of mechanisms, including altered gene expression and EC activity or impaired stem-cell mobilization and recruitment.

The transcriptional target of Gli3 and the potential cofactors that contribute to Gli3-mediated transcription have yet to be identified. The results from our gene-reporter assays suggest that Gli3 over-expression does not modulate Gli-dependent transcription in ECs, and the expression of Gli1 and Ptch1 mRNA were also unchanged. Gli3 over-expression enhanced ERK1/2 and Akt activity in ECs, but these effects may have occurred indirectly through the Gli3-induced upregulation of IL-8 and/or PD-ECGF. IL8 has been shown to promote ERK1/2 phosphorylation in ECs,39 whereas PD-ECGF promotes Akt phosphorylation in U937 cells45 and Ccl2 and CXCL3 expression in HUVECs.46 Future investigations are warranted to further characterize these mechanisms.

In conclusion, our observations indicate that Gli3 contributes to neovascularization under both ischemic and non-ischemic conditions and provide the first evidence that Gli3 contributes to angiogenesis in adult mammals. Thus, Gli3 may be a suitable therapeutic target for clinical conditions that require modulation of angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill Munger (Curis Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) for reagents, Ashley Peterson for administrative assistance, and W. Kevin Meisner, PhD, ELS, for editorial support.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL53354, R01 HL77428, R01 HL80137, and R01 HL95874).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Ad-Gli3 and Ad-LacZ

human Gli3 and β-galactosidase/GFP adenoviruses

- Ccl

CC-motif ligand

- CXCL

CXC-chemokine ligand

- DN-Akt

dominant-negative Akt

- EC

endothelial cell

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Hh

Hedgehog

- HLI

hind-limb ischemia

- HPF

high-power field

- HUVEC

human umbilical-vein endothelial cell

- IL

interleukin

- LV

left-ventricular

- LVEF

left-ventricular ejection fraction

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PD-ECGF

platelet-derived endothelial-cell growth factor

- pGli-BS, phGli3, pmGli-BS

Gli-regulated BS luciferase, human Gli3, and mutant Gli-regulated BS luciferase plasmids

- Ptch1

Patched-1

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SDS PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

- WT

wild-type

- αSMA

smooth-muscle α-actin

Footnotes

The experiments described in this report were performed at the Feinberg Cardiovascular Research Institute, Northwestern University School of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60611 USA; INSERM, U828, Pessac, France; and Université de Bordeaux Victor Ségalen, IFR4, Bordeaux, France.

Disclosures: The investigators have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Sasaki H, Nishizaki Y, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. Regulation of Gli2 and Gli3 activities by an amino-terminal repression domain: implication of Gli2 and Gli3 as primary mediators of Shh signaling. Development. 1999;126:3915–3924. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui CC, Slusarski D, Platt KA, Holmgren R, Joyner AL. Expression of three mouse homologs of the Drosophila segment polarity gene cubitus interruptus, Gli, Gli-2, and Gli-3, in ectoderm- and mesoderm-derived tissues suggests multiple roles during postimplantation development. Dev Biol. 1994;162:402–413. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walterhouse D, Ahmed M, Slusarski D, Kalamaras J, Boucher D, Holmgren R, Iannaccone P. gli, a zinc finger transcription factor and oncogene, is expressed during normal mouse development. Dev Dyn. 1993;196:91–102. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001960203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litingtung Y, Chiang C. Specification of ventral neuron types is mediated by an antagonistic interaction between Shh and Gli3. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:979–985. doi: 10.1038/79916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rallu M, Machold R, Gaiano N, Corbin JG, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Dorsoventral patterning is established in the telencephalon of mutants lacking both Gli3 and Hedgehog signaling. Development. 2002;129:4963–4974. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litingtung Y, Dahn RD, Li Y, Fallon JF, Chiang C. Shh and Gli3 are dispensable for limb skeleton formation but regulate digit number and identity. Nature. 2002;418:979–983. doi: 10.1038/nature01033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.te Welscher P, Zuniga A, Kuijper S, Drenth T, Goedemans HJ, Meijlink F, Zeller R. Progression of vertebrate limb development through SHH-mediated counteraction of GLI3. Science. 2002;298:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1075620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grindley JC, Bellusci S, Perkins D, Hogan BL. Evidence for the involvement of the Gli gene family in embryonic mouse lung development. Dev Biol. 1997;188:337–348. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Latif A, Bolli R, Tleyjeh IM, Montori VM, Perin EC, Hornung CA, Zuba-Surma EK, Al-Mallah M, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow-derived cells for cardiac repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott A, Gustafsson M, Elsam T, Hui CC, Emerson CP, Jr, Borycki AG. Gli2 and Gli3 have redundant and context-dependent function in skeletal muscle formation. Development. 2005;132:345–357. doi: 10.1242/dev.01537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motoyama J. Essential roles of Gli3 and sonic hedgehog in pattern formation and developmental anomalies caused by their dysfunction. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2006;46:123–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2006.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai P, Akimaru H, Tanaka Y, Maekawa T, Nakafuku M, Ishii S. Sonic Hedgehog-induced activation of the Gli1 promoter is mediated by GLI3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8143–8152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Knezevic V, Ervin V, Hutson R, Ward Y, Mackem S. Direct interaction with Hoxd proteins reverses Gli3-repressor function to promote digit formation downstream of Shh. Development. 2004;131:2339–2347. doi: 10.1242/dev.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Ruther U, Wang B. The Shh-independent activator function of the full-length Gli3 protein and its role in vertebrate limb digit patterning. Dev Biol. 2007;305:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vortkamp A, Gessler M, Grzeschik KH. GLI3 zinc-finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature. 1991;352:539–540. doi: 10.1038/352539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang S, Graham JM, Jr, Olney AH, Biesecker LG. GLI3 frameshift mutations cause autosomal dominant Pallister-Hall syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pola R, Ling LE, Aprahamian TR, Barban E, Bosch-Marce M, Curry C, Corbley M, Kearney M, Isner JM, Losordo DW. Postnatal recapitulation of embryonic hedgehog pathway in response to skeletal muscle ischemia. Circulation. 2003;108:479–485. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080338.60981.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pola R, Ling LE, Silver M, Corbley MJ, Kearney M, Blake Pepinsky R, Shapiro R, Taylor FR, Baker DP, Asahara T, Isner JM. The morphogen Sonic hedgehog is an indirect angiogenic agent upregulating two families of angiogenic growth factors. Nat Med. 2001;7:706–711. doi: 10.1038/89083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asai J, Takenaka H, Kusano KF, Ii M, Luedemann C, Curry C, Eaton E, Iwakura A, Tsutsumi Y, Hamada H, Kishimoto S, Thorne T, Kishore R, Losordo DW. Topical sonic hedgehog gene therapy accelerates wound healing in diabetes by enhancing endothelial progenitor cell-mediated microvascular remodeling. Circulation. 2006;113:2413–2424. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.603167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusano KF, Pola R, Murayama T, Curry C, Kawamoto A, Iwakura A, Shintani S, Ii M, Asai J, Tkebuchava T, Thorne T, Takenaka H, Aikawa R, Goukassian D, von Samson P, Hamada H, Yoon YS, Silver M, Eaton E, Ma H, Heyd L, Kearney M, Munger W, Porter JA, Kishore R, Losordo DW. Sonic hedgehog myocardial gene therapy: tissue repair through transient reconstitution of embryonic signaling. Nat Med. 2005;11:1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/nm1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renault MA, Roncalli J, Tongers J, Hamada H, Thorne T, Misener S, Ito A, Clarke T, Millay M, Scarpelli A, Klyachko E, Losordo DW. Abstract 5445: Gli2 and Gli3 are over-expressed in the ischemic tissue and participate in ischemia-induced angiogenesis and myogenesis. Circulation. 2008;118:S551. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couffinhal T, Silver M, Zheng LP, Kearney M, Witzenbichler B, Isner JM. Mouse model of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1667–1679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenyon BM, Voest EE, Chen CC, Flynn E, Folkman J, D'Amato RJ. A model of angiogenesis in the mouse cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1652–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers MS, Birsner AE, D'Amato RJ. The mouse cornea micropocket angiogenesis assay. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2545–2550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buttitta L, Mo R, Hui CC, Fan CM. Interplays of Gli2 and Gli3 and their requirement in mediating Shh-dependent sclerotome induction. Development. 2003;130:6233–6243. doi: 10.1242/dev.00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skurk C, Maatz H, Kim HS, Yang J, Abid MR, Aird WC, Walsh K. The Akt-regulated forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a controls endothelial cell viability through modulation of the caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1513–1525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki H, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development. 1997;124:1313–1322. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renault MA, Jalvy S, Belloc I, Pasquet S, Sena S, Olive M, Desgranges C, Gadeau AP. AP-1 is involved in UTP-induced osteopontin expression in arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:674–681. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000094747.05021.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fu JR, Liu WL, Zhou JF, Sun HY, Xu HZ, Luo L, Zhang H, Zhou YF. Sonic hedgehog protein promotes bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell proliferation, migration and VEGF production via PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:685–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanda S, Mochizuki Y, Suematsu T, Miyata Y, Nomata K, Kanetake H. Sonic hedgehog induces capillary morphogenesis by endothelial cells through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8244–8249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riobo NA, Lu K, Ai X, Haines GM, Emerson CP., Jr Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt are essential for Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4505–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504337103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riobo NA, Haines GM, Emerson CP., Jr Protein kinase C-delta and mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 control GLI activation in hedgehog signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:839–845. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Autiero M, De Smet F, Claes F, Carmeliet P. Role of neural guidance signals in blood vessel navigation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:629–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park KW, Crouse D, Lee M, Karnik SK, Sorensen LK, Murphy KJ, Kuo CJ, Li DY. The axonal attractant Netrin-1 is an angiogenic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16210–16215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson BD, Ii M, Park KW, Suli A, Sorensen LK, Larrieu-Lahargue F, Urness LD, Suh W, Asai J, Kock GA, Thorne T, Silver M, Thomas KR, Chien CB, Losordo DW, Li DY. Netrins promote developmental and therapeutic angiogenesis. Science. 2006;313:640–644. doi: 10.1126/science.1124704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawasaki T, Ito K, Hirata T. Netrin 1 regulates ventral tangential migration of guidepost neurons in the lateral olfactory tract. Development. 2006;133:845–853. doi: 10.1242/dev.02257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomioka N, Osumi N, Sato Y, Inoue T, Nakamura S, Fujisawa H, Hirata T. Neocortical origin and tangential migration of guidepost neurons in the lateral olfactory tract. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5802–5812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05802.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Gomperts BN, Belperio JA, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:593–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heidemann J, Ogawa H, Dwinell MB, Rafiee P, Maaser C, Gockel HR, Otterson MF, Ota DM, Lugering N, Domschke W, Binion DG. Angiogenic effects of interleukin 8 (CXCL8) in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells are mediated by CXCR2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8508–8515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelus LM, Fukuda S. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization: the CXCR2 ligand GRObeta rapidly mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells with enhanced engraftment properties. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hristov M, Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Liehn EA, Shagdarsuren E, Ludwig A, Weber C. Importance of CXC chemokine receptor 2 in the homing of human peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cells to sites of arterial injury. Circ Res. 2007;100:590–597. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259043.42571.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Bonaros N, Lietz K, Xiang G, Martens TP, Kurlansky PA, Sondermeijer H, Witkowski P, Boyle A, Homma S, Wang SF, Itescu S. Myocardial homing and neovascularization by human bone marrow angioblasts is regulated by IL-8/Gro CXC chemokines. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Tanaka K, Ihaya A, Fujibayashi Y, Takamatsu S, Morioka K, Sasaki M, Uesaka T, Kimura T, Yamada N, Tsuda T, Chiba Y. Gene therapy for chronic myocardial ischemia using platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H408–415. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00176.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada N, Li W, Ihaya A, Kimura T, Morioka K, Uesaka T, Takamori A, Handa M, Tanabe S, Tanaka K. Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor gene therapy for limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeung HC, Che XF, Haraguchi M, Zhao HY, Furukawa T, Gotanda T, Zheng CL, Tsuneyoshi K, Sumizawa T, Roh JK, Akiyama S. Protection against DNA damage-induced apoptosis by the angiogenic factor thymidine phosphorylase. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunningham SP, Currie MJ, Morrin HR, Tan EY, Turley H, Dachs GU, Watson AI, Frampton C, Robinson BA, Fox SB. The angiogenic factor thymidine phosphorylase up-regulates the cell adhesion molecule P-selectin in human vascular endothelial cells and is associated with P-selectin expression in breast cancers. J Pathol. 2007;212:335–344. doi: 10.1002/path.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.