Abstract

Context

Ozone exposure triggers airway inflammatory responses that may be influenced by biologically active purine metabolites.

Objective

Examine the relationships between airway purine metabolites and established inflammatory markers of ozone exposure, and determine if these relationships are altered in individuals with atopy or asthma.

Materials and Methods

Mass spectrometry was utilized to measure concentrations of purine metabolites (AMP, adenosine, hypoxanthine, uric acid) and non-purine metabolites (taurine, urea, phenylalanine, tyrosine) in induced sputum obtained from 31 subjects with normal lung function (13 healthy controls, 8 atopic non-asthmatics, and 10 atopic asthmatic) before and four hours after ozone exposure.

Results

At baseline, the purines AMP and hypoxanthine correlated with multiple inflammatory markers including neutrophil counts and the cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β (r ranged from 0.41–0.66, all p<0.05). Following ozone exposure, these purines remained correlated with IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (r=0.37-0.68). However, AMP and hypoxanthine increased significantly post ozone exposure in atopic nonasthmatics but not atopic asthmatics. In contrast, the non-purine metabolite taurine correlated with baseline neutrophil counts (r=0.56) and IL-6 (r=0.53) and was elevated post exposure in both atopic cohorts.

Discussion and Conclusions

The purine metabolites AMP and hypoxanthine are correlated with multiple inflammatory markers at baseline and after ozone exposure. However, changes in these purine metabolites after ozone appear to differ from other inflammatory markers, with less response in atopic asthmatics relative to atopic nonasthmatics. Purine metabolites may play a role in the signaling responses to ozone, but these responses may be altered in subjects with asthma.

Keywords: Induced sputum, adenosine, adenosine monophosphate, hypoxanthine, taurine

Introduction

Ozone is a common environmental pollutant that has been strongly linked to increased morbidity from respiratory diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Ciencewicki et al., 2008). Exposure to ozone leads to oxidative stress that can trigger inflammatory airway responses, including neutrophilic inflammation (Hollingsworth et al., 2007). Recent evidence suggests that these inflammatory responses are enhanced in sensitive individuals such as those with atopy or asthma (Hernandez et al., 2010).

Previous studies suggest that exposure to ozone is mediated through production of “danger signals” of oxidative stress that lead to innate immune responses (Depuydt et al., 2002). Interestingly, extracellular purines – biologically active molecules including ATP and its metabolites – have also been shown to function as danger signals in response to a variety of noxious stimuli (Bours et al., 2006). More directly, exposure of airway epithelial cells to ozone has been shown to increase release of ATP into the extracellular space (Ahmad et al., 2005). Furthermore, the purine metabolites that result from metabolism of this extracellular ATP (Burnstock, 2006a) have also been linked to physiological pathways relevant to oxidative stress responses. For example, AMP has been shown to correlate with markers of neutrophilic airway inflammation (Loughlin et al., 2009, Esther et al., 2008a), which increase in response to ozone exposure (Seltzer et al., 1986). Adenosine-mediated signaling also influences a variety of inflammatory responses (Mohsenin and Blackburn, 2006), and airway concentrations of this purine are elevated in stable asthmatic subjects (Huszar et al., 2002, Esther et al., 2009, Loughlin et al., 2009, Driver et al., 1993) and are sensitive to exacerbations and effective treatment (Csoma et al., 2005). Adenosine can be further metabolized to hypoxanthine and uric acid, compounds that have also been linked to responses to oxidative stress (Hee Sun et al., 2009), with uric acid a known activator of inflammasomes (Gasse et al., 2009).

These findings suggest that purine metabolites may be involved in the response to ozone exposure, and that purinergic responses might be enhanced in sensitive subjects with atopy and/or asthma. To address these hypotheses, we examined sputum supernatants available from a previously published study of ozone exposure in a group of subjects with normal lung function that included healthy normal volunteers, atopic non-asthmatics, and atopic asthmatics (Hernandez et al., 2010). These samples were analyzed using a mass spectrometric method capable of measuring multiple purine metabolites including AMP, adenosine, hypoxanthine, and uric acid. In addition, measurement of several non-purine metabolites (urea, taurine, phenylalanine, tyrosine) for which mass spectrometric methods have been established were included to assess whether observed relationships were specific to purines. These non-purine metabolites included the sulfa-amino acid taurine that has previously been linked to neutrophilic inflammation (Witko-Sarsat et al., 1995, Learn et al., 1990).

Methods

Subjects and samples

Subjects represented a subset of participants in a previously published study of ozone exposure (13 healthy normal volunteers [NV], 8 atopic non-asthmatics with allergic rhinitis [AR], and 10 atopic asthmatics [AA]) (Hernandez et al., 2010) in whom induced sputum supernatants obtained before and after ozone exposure were available. As previously described, the groups were defined on the basis of skin prick testing (atopic vs. nonatopic) and methacholine challenge (asthmatic vs. non-asthmatic). All asthmatics also had a physician diagnosis of mild intermittent asthma and were not on any long term controller medication (inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene receptor antagonist). Atopic subjects could utilize antihistamines or topical nasal steroids to control allergic rhinitis. All subjects were free of respiratory symptoms for at least 4 weeks prior to the study. Demographic features of these subjects are shown in Table 1. Each subject was exposed to 0.4 ppm ozone for 2 hours while performing four 15 minute sessions of intermittent moderate exercise separated by 15 minutes of seated rest. Sputum was obtained pre-exposure and again 4-6 hours post exposure. Methods for sputum induction and processing, lung function testing, and assessing sputum cell counts and cytokine concentrations were as previously described (Hernandez et al., 2010); the reference set for percent predicted lung function values was from Knudson (Knudson et al., 1976). Samples were collected between April 2006 and August 2009 and stored at −80 oC until analysis in October 2010. There were no significant between group differences in time of storage, and no significant correlations were observed between time of storage and concentrations of any metabolite.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Response to Ozone

| Demographics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | Divided by Cohort | |||

| NV | AR | AA | ||

| n= | 31 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| Age (years) | 24.9 ± 5.6 | 23.7 ± 5.0 | 25.3 ± 5.4 | 26.1 ± 6.8 |

| Gender | 16M/ 15F | 6M/ 7F | 5M/ 3F | 5M/ 5F |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 64.5% | 61.5% | 62.5% | 70.0% |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 26.2 ± 5.4 | 27.0 ± 6.1 | 26.2 ± 5.6 | 25.2 ± 4.6 |

| Response to Ozone | ||||

| All | NV | AR | AA | |

| % predicted FEV1 – pre O3 | 100.1 ± 12.1 | 102.1 ± 12.7 | 101.2 ± 12.1 | 96.8 ± 12 |

| % predicted FEV1 - post O3 | 83.8 ± 13* | 84.2 ± 13.3* | 87.1 ± 9.0* | 80.8 ± 15.6* |

| PMN counts - pre O3 | 564 ± 736 | 470 ± 660 | 560 ± 780 | 680 ± 860 |

| PMN counts - post O3 | 928 ± 992* | 720 ± 710 | 920 ± 1140 | 1160 ± 1170 |

p<0.05 versus pre O3. NV = healthy normal volunteers, AR = atopic nonasthmatics (allergic rhinitis), AA = atopic asthmatics, O3 = ozone, PMN = neutrophil (polymorpholeukocyte).

Mass spectrometric analysis

Prior to analysis, a solution of isotopically labeled internal standards was added to each sputum supernatant sample to a final concentration of 50 nM [13C, 15N] adenosine, 250 nM [15N] AMP, and 50 μM [13C] urea plus the working concentration of an isotopically labeled amino acid solution (NSK-A, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA). Sample plus internal standard was then filtered through a 10 kDa column for 30 minutes at 11,000 x g at 4 degrees to remove macromolecules.

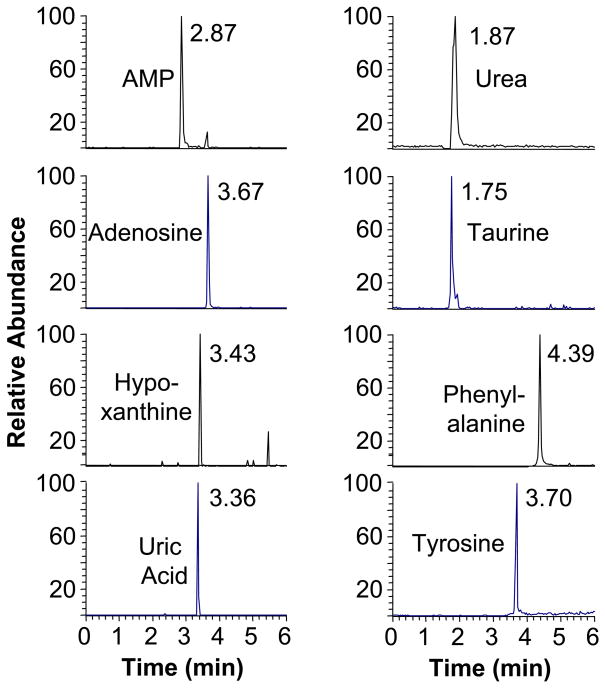

Mass spectrometry was performed using an liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system with electrospray ionization interface including an Acquity solvent manager and a TSQ-Quantum Ultra Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose). 5 μl of sample was injected onto an Atlantis T3 C18, 1.8 μm column (Waters, Milford MA) operated with a methanol and 0.1% formic acid gradients as previously described (Esther et al., 2008b). Mass spectrometric detection (Figure 1) was performed in multiple reaction monitoring mode using appropriate transitions in mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) from parent to product ion during tandem mass spectrometry for the purine metabolites AMP (m/z transition 348→136), adenosine (268→136), hypoxanthine (135→92) and uric acid (167→124) plus a select group of non-purine metabolites with which we have previous experience including urea (61→44), taurine (124→80), phenylalanine (166→120), and tyrosine (182→136). In addition, ion transitions were monitored for the isotopically labeled AMP (353→141), adenosine (283→151), urea (62→45), phenylalanine (172→126), and tyrosine (188→171) as internal standards. All ions were monitored in positive mode except for hypoxanthine, uric acid and taurine, which were monitored in negative mode. Mass spectrometric signal was defined as the ratio of the peak area of the metabolite divided by the peak area of the relevant internal standard. Hypoxanthine and uric acid utilized the adenosine internal standard, taurine the urea internal standard based on similar column run times. Metabolite concentrations were determined by analysis of standard solutions run in parallel.

Figure 1.

Mass spectrometric chromatogram demonstrating detection of several purine metabolites (left) and non-purine metabolites (right) from a sputum sample. The column run time for each peak is shown.

All compounds were detected in all samples (Figure 1), except for one sample in which taurine was below detection limits. In addition, 10 of the 62 samples analyzed (three healthy control, two atopic non-asthmatic, five atopic asthmatic samples) exhibited extensive degradation of the AMP internal standard (but not adenosine or other internal standards), suggesting high ectonuclease activity. Because this high activity could alter concentrations of both AMP and adenosine (the product of AMP hydrolysis), these samples were excluded from analysis for adenosine and AMP.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. All sputa data were log transformed prior to analysis to yield normalized datasets, as determined by the D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Correlations were determined using Pearson correlation coefficients. Changes after ozone exposure were assessed using paired Student’s T-tests.

Results

Sputum supernatant samples obtained before and after ozone exposure were available from 31 subjects including 13 healthy controls, 8 atopic non-asthmatics, and 10 atopic asthmatics. These subjects represented a subset of the subjects included in a previously published study (Hernandez et al., 2010), and demographic characteristics in this subset were similar to those of the larger group and did not exhibit any significant between group differences (Table 1). Lung function as assessed by percent predicted FEV1 was within the normal range at baseline but significantly decreased post ozone exposure in the group as a whole and in all individual cohorts (Table 1). Sputum neutrophil counts (cells/mg) also increased after ozone exposure when all subjects were combined (p<0.01), although increases observed within the individual cohorts did not reach statistical significance. Of note, increases in neutrophil counts post ozone exposure reached statistical significance in atopic non-asthmatic and atopic asthmatic cohorts within the larger study (Hernandez et al., 2010).

Because several purine metabolites have been previously linked to inflammatory responses (Burnstock, 2006b), the relationships between sputum purine metabolites and established markers of inflammation were assessed. In the baseline, pre-exposure samples, the purine metabolites AMP and hypoxanthine were significantly correlated with multiple markers of inflammation including sputum neutrophil counts and the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (Table 2). In addition, adenosine was statistically significantly correlated with the cytokines IL-6 and IL-8, with a correlation to neutrophil counts that did not reach statistical significance (r=0.40, p=0.0504). In contrast, no significant correlations were observed between uric acid and any inflammatory marker (not shown). Among the non-purine metabolites, only taurine exhibited any significant correlation to inflammatory markers with correlations to neutrophil counts and IL-6 (Table 2). Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and urea were not correlated with any inflammatory marker (not shown).

Table 2.

Purine metabolite correlations to inflammatory markers and concentrations pre and post ozone exposure in all subjects

| AMP | Adenosine | Hypoxanthine | Taurine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Correlations pre and post ozone exposure | ||||||||

| PMNs/mg sputum | 0.41 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.56 | n.s. |

| IL-1β | 0.41 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.56 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| IL-6 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.46 | n.s. | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.53 |

| IL-8 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.43 | n.s. | 0.66 | 0.37 | n.s. | n.s. |

| TNFα | 0.53 | 0.63 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.48 | n.s. | 0.52 |

| Concentrations pre and post ozone exposure | ||||||||

| Concentration (nM) | 195 ± 169 | 308 ± 343 | 348 ± 312 | 321 ± 378 | 286 ± 243 | 369 ± 360 | 609 ± 499 | 897 ± 665* |

For correlations, p<0.05 for all numeric values, bold values p<0.01. For concentrations, all values are shown.

p<0.01 vs. Pre.

In the sputum samples obtained post ozone exposure, the purine metabolites AMP and hypoxanthine remained significantly correlated with the cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (Table 2). Adenosine was not correlated with any inflammatory marker post ozone exposure. Of the non-purine metabolites, taurine remained correlated with IL-6 and exhibited a modest correlation with TNF-α. No purine or non-purine metabolite was correlated with sputum neutrophil counts post ozone exposure, and the metabolites uric acid, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and urea were not significantly correlated with any inflammatory marker in these samples.

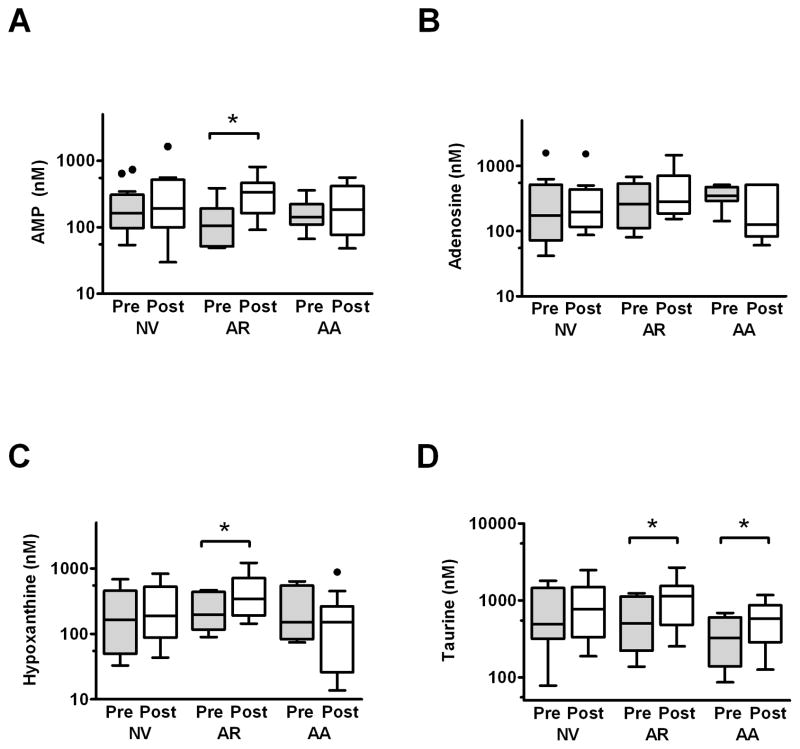

These data suggested that sputum concentrations of AMP and hypoxanthine, and to a lesser extent adenosine and taurine, were significantly correlated with markers of inflammation both before and after ozone exposure. Therefore, we examined whether exposure to ozone altered concentrations of any of these metabolites comparable to the statistically significant increases we observed in neutrophil counts (Table 1) and in the cytokines IL-6 (138±141 pg/ml pre, 264±360 pg/ml post, p<0.05) and IL-8 (24.2±32.4 ng/ml pre, 35.9±46.4 ng/ml post, p<0.05) within the group as a whole.. Interestingly, although we observed the predicted increase in sputum taurine following ozone exposure (Table 2), changes in the purines AMP and hypoxanthine did not reach statistical significance. Because our previous study suggested that inflammatory responses to ozone are increased in subjects with atopy and/or asthma (Hernandez et al., 2010), we reexamined the data with the groups stratified by cohort. In these evaluations, significant increases in AMP and hypoxanthine were observed in the atopic nonasthmatics, but not healthy controls or atopic asthmatics (Figure 2A-C). Overall, the magnitude of change in hypoxanthine was higher in atopic nonasthmatics (increase of 0.24±0.22 log units) than in atopic asthmatics (-0.23±0.48 log units, p<0.05), with similar pattern for AMP (increase of 0.34±0.31 log units atopic nonasthmatics, 0.00±0.29 log units atopic asthmatics) not reaching statistical significance (p=0.095). In contrast, taurine increased significantly in both atopic nonasthmatic and atopic asthmatic cohorts (Figure 2D), and the magnitude of change was similar in both atopic cohorts (increase of 0.32±0.34 log units in atopic asthmatics, 0.23±0.28 log units in atopic nonasthmatics, p=0.60). No statistically significant changes for any purine or non-purine compound were observed in healthy normal volunteers, and no statistically significant changes in adenosine (Figure 2B), uric acid, urea, phenylalanine, or tyrosine (not shown) were observed in any cohort. Of note, we did not observe any statistically significant differences in baseline pre- exposure metabolite concentrations, with an approximately ~0.2 log unit increase in the asthma cohort relative to the healthy controls not reaching statistical significance (p=0.25).

Figure 2.

Concentrations pre (grey bars) and post (white bars) ozone exposure were analyzed for the metabolites correlated with neutrophil counts in baseline samples: AMP (A), Ado (B), hypoxanthine (C) and taurine (D). Significant increases after ozone exposure were noted for AMP and hypoxanthine in the atopic nonasthmatics with allergic rhinitis (AR) but not the atopic asthmatics (AA) or healthy normal volunteers (NV). In contrast, sputum taurine increased significantly in both atopic groups. Data are shown a box-plots with whiskers as defined by Tukey (1.5x the intraquartile range). * = p<0.05 pre vs. post, with analyses performed on log-transformed mean values not depicted on the figure.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that two purine metabolites – AMP and hypoxanthine –were significantly correlated with multiple inflammatory markers that included neutrophil counts and pro inflammatory cytokines both at baseline and following exposure to inhaled ozone. These correlations were particularly robust for the cytokines IL-6 and IL-8, which have been well established as biomarkers of ozone induced inflammation (Devlin et al., 1991, Jaspers et al., 1997, Hernandez et al., 2010). Interestingly, although adenosine has also been linked to ozone mediated inflammatory responses (particularly via IL-6) (Sun et al., 2008, Sitaraman et al., 2001), the correlations between adenosine and inflammatory markers were less robust than for other purine metabolites in this study. Similarly, no relationships were observed between uric acid and inflammatory markers despite previous studies suggesting that uric acid concentrations may influence inflammasome function (Gasse et al., 2009). However, the samples obtained during this study reflected only a single, relatively early (4 hour) time point after ozone exposure, and it is possible that some relationships between purine metabolites and ozone mediated inflammatory processes may be present at other time frames. Furthermore, since subjects exercised during ozone exposure, we cannot rule out the possibility that exercise contributed to the observed changes. However, we note that exercise alone did not induce changes in sputum inflammatory markers in a previous, similar study (Lay et al., 2007).

The correlations we observed between inflammatory markers and the purine metabolites AMP and hypoxanthine are consistent with findings from previous studies. Correlations between AMP and neutrophils have been observed in several studies of respiratory samples (Esther et al., 2008a, Eltzschig et al., 2006, Loughlin et al., 2009), and elevated AMP concentrations have been detected in airway samples from patients with cystic fibrosis, a disease associated with significant neutrophilic airway inflammation (Esther et al., 2009, Esther et al., 2008a). The mechanisms that underlie these relationships are not clear, but may reflect release of ATP and accumulation of AMP directly by neutrophils (Lennon et al., 1998, Chen et al., 2006). Indeed, ozone has been shown to trigger release of ATP from airway epithelial cells (Ahmad et al., 2005), suggesting that the purine metabolites measured in this study may be derived from metabolism of ATP. Unfortunately, the mass spectrometric method used in this study was not sufficiently sensitive to measure ATP directly. The relationships between hypoxanthine and airway inflammation have been less well defined, but this purine metabolite is strongly linked to oxidative injury (Hee Sun et al., 2009) and has been found to be elevated in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (Quinlan et al., 1997).

Interestingly, while AMP and hypoxanthine were correlated with multiple inflammatory markers before and after ozone exposure, statistically significant increases in these metabolites after exposure to ozone were not observed within the group as a whole. Examination of the group stratified by cohort suggested that the responses of hypoxanthine (and likely AMP) were diminished in the atopic asthmatic cohorts relative to the atopic nonasthmatics. This contrasts to our experience with other inflammatory markers, in which the responses to ozone are generally enhanced in atopic asthmatics (Hernandez et al., 2010).

These findings suggest the possibility that the purinergic component of the response to ozone may be reduced in the airways of subjects with atopic asthma relative to other atopic individuals. If true, a reduced purinergic response to ozone in asthmatics would be somewhat surprising, since several studies have demonstrated that airway adenosine concentrations are elevated in asthmatic subjects (Huszar et al., 2002, Driver et al., 1993, Loughlin et al., 2009) and increase after exposure to bronchoconstrictive stimuli such as exercise or allergen (Csoma et al., 2005, Huszar et al., 2002, Vizi et al., 2002). However, responses to ozone differ from those to other stimuli, with a more prominent neutrophilic component in contrast to the predominant eosinophilic response to allergen (Ciencewicki et al., 2008). Indeed, while adenosine has been identified as the primary purine altered in asthma and other diseases, we did not observe changes in adenosine after ozone exposure in the group as a whole or within any cohort, although this relatively small exploratory study may have been insufficiently powered to detect these changes.

Purinergic signaling pathways are known to modulate inflammatory responses (Burnstock, 2006b), suggesting that the purinergic responses observed in this study may influence other inflammatory cascades. In particular, adenosine mediated signaling has been shown to have both positive and negative immunomodulatory effects (Vass and Horvath, 2008) which can be mediated both by both adenosine present in extracellular fluid and by local generation of adenosine from AMP via nuclease activity at epithelial surfaces (Eltzschig et al., 2006). While adenosine mediated signaling alone tends to increase production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 (Sun et al., 2008), increased concentrations of adenosine have also been shown to attenuate release of IL-6 in response to other inflammatory stimuli such as LPS (Hasko et al., 1996). Consistent with this observations, the atopic asthmatic group that appeared to have decreased purinergic responses in this study also had the largest increase in ozone stimulated IL-6 production in the larger study from which these samples were drawn (Hernandez et al., 2010). While these associations between purines and other inflammatory mediators are intriguing, more definitive elucidation of these relationships will require further study.

It is feasible that the findings of this study are non-specific artifacts of the sample collection or analytic methods. However, the fact that we did not observe correlations between inflammatory markers and several non-purine metabolites (urea, phenylalanine, tyrosine) argues against this hypothesis. Furthermore, the relationships between sputum taurine and markers of inflammation are consistent with previous studies of this metabolite. Taurine is found at high concentrations within human neutrophils (Fukuda et al., 1982), and elevated sputum taurine concentrations have been observed to correlate with markers of inflammation in CF patients (Witko-Sarsat et al., 1995). Thus, the relationships between sputum taurine and neutrophil counts and its increase after ozone exposure are consistent with predictions and lend further credence to the analytic methods used in this study.

Conclusions

In summary, our study suggests that purine metabolites – particularly AMP and hypoxanthine — are correlated with inflammatory markers of ozone exposure. However, the analyses suggest the possibility that the purinergic component of the response to ozone may be diminished in atopic asthmatics relative to other atopic individuals. While interesting, these findings will need to be confirmed through further study in a larger cohort of individuals.

Abbreviations

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- ATP

adenosine tri-phosphate

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest

CRE was supported by NHLBI grant 1K23HL089708 and NIEHS grant P30 ES-10126. DBP, and MLH were supported by NIEHS grants R01ES012706 and P30ES010126, NIAID grant U19AI077437, NCCAM grant P01AT002620, NCRR NIH grants KL2RR025746, M01RR00046 and UL1RR025747, as well as US EPA grant CR 83346301.

References

- AHMAD S, AHMAD A, MCCONVILLE G, SCHNEIDER BK, ALLEN CB, MANZER R, MASON RJ, WHITE CW. Lung epithelial cells release ATP during ozone exposure: signaling for cell survival. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:213–26. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOURS MJ, SWENNEN EL, DI VIRGILIO F, CRONSTEIN BN, DAGNELIE PC. Adenosine 5'-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Pathophysiology and therapeutic potential of purinergic signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2006a;58:58–86. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Purinergic signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2006b;147(Suppl 1):S172–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y, CORRIDEN R, INOUE Y, YIP L, HASHIGUCHI N, ZINKERNAGEL A, NIZET V, INSEL PA, JUNGER WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIENCEWICKI J, TRIVEDI S, KLEEBERGER SR. Oxidants and the pathogenesis of lung diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:456–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSOMA Z, HUSZAR E, VIZI E, VASS G, SZABO Z, HERJAVECZ I, KOLLAI M, HORVATH I. Adenosine level in exhaled breath increases during exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:873–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEPUYDT PO, LAMBRECHT BN, JOOS GF, PAUWELS RA. Effect of ozone exposure on allergic sensitization and airway inflammation induced by dendritic cells. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2002;32:391–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVLIN RB, MCDONNELL WF, MANN R, BECKER S, HOUSE DE, SCHREINEMACHERS D, KOREN HS. Exposure of humans to ambient levels of ozone for 6.6 hours causes cellular and biochemical changes in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:72–81. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRIVER AG, KUKOLY CA, ALI S, MUSTAFA SJ. Adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:91–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELTZSCHIG HK, WEISSMULLER T, MAGER A, ECKLE T. Nucleotide metabolism and cell-cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:73–87. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESTHER CR, JR, ALEXIS NE, CLAS ML, LAZAROWSKI ER, DONALDSON SH, RIBEIRO CM, MOORE CG, DAVIS SD, BOUCHER RC. Extracellular purines are biomarkers of neutrophilic airway inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2008a;31:949–56. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00089807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESTHER CR, JR, BOYSEN G, OLSEN BM, COLLINS LB, GHIO AJ, SWENBERG JW, BOUCHER RC. Mass spectrometric analysis of biomarkers and dilution markers in exhaled breath condensate reveals elevated purines in asthma and cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L987–993. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90512.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESTHER CR, JR, JASIN HM, COLLINS LB, SWENBERG JA, BOYSEN G. A mass spectrometric method to simultaneously measure a biomarker and dilution marker in exhaled breath condensate. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008b;22:701–5. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKUDA K, HIRAI Y, YOSHIDA H, NAKAJIMA T, USUI T. Free amino acid content of lymphocytes and granulocytes compared. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1758–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASSE P, RITEAU N, CHARRON S, GIRRE S, FICK L, PETRILLI V, TSCHOPP J, LAGENTE V, QUESNIAUX VFJ, RYFFEL B, COUILLIN I. Uric Acid Is a Danger Signal Activating NALP3 Inflammasome in Lung Injury Inflammation and Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:903–913. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1274OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASKO G, SZABO C, NEMETH ZH, KVETAN V, PASTORES SM, VIZI ES. Adenosine receptor agonists differentially regulate IL-10, TNF-alpha, and nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages and in endotoxemic mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:4634–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEE SUN P, SO RI KIM, YONG CHUL LEE. Impact of oxidative stress on lung diseases. Respirology. 2009;14:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERNANDEZ ML, LAY JC, HARRIS B, ESTHER CR, JR, BRICKEY WJ, BROMBERG PA, DIAZ-SANCHEZ D, DEVLIN RB, KLEEBERGER SR, ALEXIS NE, PEDEN DB. Atopic asthmatic subjects but not atopic subjects without asthma have enhanced inflammatory response to ozone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:537–544.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLINGSWORTH JW, KLEEBERGER SR, FOSTER WM. Ozone and pulmonary innate immunity. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:240–6. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-023AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUSZAR E, VASS G, VIZI E, CSOMA Z, BARAT E, MOLNAR VILAGOS G, HERJAVECZ I, HORVATH I. Adenosine in exhaled breath condensate in healthy volunteers and in patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1393–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASPERS I, FLESCHER E, CHEN LC. Ozone-induced IL-8 expression and transcription factor binding in respiratory epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1997;272:L504–511. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.3.L504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNUDSON RJ, SLATIN RC, LEBOWITZ MD, BURROWS B. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve. Normal standards, variability, and effects of age. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;113:587–600. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAY JC, ALEXIS NE, KLEEBERGER SR, ROUBEY RA, HARRIS BD, BROMBERG PA, HAZUCHA MJ, DEVLIN RB, PEDEN DB. Ozone enhances markers of innate immunity and antigen presentation on airway monocytes in healthy individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:719–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEARN DB, FRIED VA, THOMAS EL. Taurine and hypotaurine content of human leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1990;48:174–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LENNON PF, TAYLOR CT, STAHL GL, COLGAN SP. Neutrophil-derived 5'-adenosine monophosphate promotes endothelial barrier function via CD73-mediated conversion to adenosine and endothelial A2B receptor activation. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1433–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOUGHLIN CE, ESTHER CR, JR, LAZAROWSKI ER, ALEXIS NE, PEDEN DB. Neutrophilic inflammation is associated with altered airway hydration in stable asthmatics. Respir Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHSENIN A, BLACKBURN MR. Adenosine signaling in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:54–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000199002.46038.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUINLAN GJ, LAMB NJ, TILLEY R, EVANS TW, GUTTERIDGE JM. Plasma hypoxanthine levels in ARDS: implications for oxidative stress, morbidity, and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:479–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELTZER J, BIGBY BG, STULBARG M, HOLTZMAN MJ, NADEL JA, UEKI IF, LEIKAUF GD, GOETZL EJ, BOUSHEY HA. O3-induced change in bronchial reactivity to methacholine and airway inflammation in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:1321–1326. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.4.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SITARAMAN SV, MERLIN D, WANG L, WONG M, GEWIRTZ AT, SI-TAHAR M, MADARA JL. Neutrophil-epithelial crosstalk at the intestinal lumenal surface mediated by reciprocal secretion of adenosine and IL-6. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:861–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI11783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN Y, WU F, SUN F, HUANG P. Adenosine Promotes IL-6 Release in Airway Epithelia. J Immunol. 2008;180:4173–4181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VASS G, HORVATH I. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the pathomechanism and treatment of respiratory diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:917–22. doi: 10.2174/092986708783955392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIZI E, HUSZAR E, CSOMA Z, BOSZORMENYI-NAGY G, BARAT E, HORVATH I, HERJAVECZ I, KOLLAI M. Plasma adenosine concentration increases during exercise: a possible contributing factor in exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:446–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKO-SARSAT V, DELACOURT C, RABIER D, BARDET J, NGUYEN AT, DESCAMPS-LATSCHA B. Neutrophil-derived long-lived oxidants in cystic fibrosis sputum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1910–1916. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]