Abstract

Interleukin (IL) 33 has been recently identified as a ligand to the ST2 receptor that mediates Th2-dominant allergic inflammation. The purpose of this study was to explore the role of toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated innate immunity in IL-33 induction by mucosal epithelium. Human corneal tissues and cultured primary human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) were treated with a variety of viral or bacterial components without or with different inhibitors to evaluate the IL-33 regulation and signaling pathways. The level of mRNA expression was determined by reverse transcription and real time PCR, and protein was measured by ELISA, immunostaining and Western blotting. IL-33 mRNA and protein were largely induced by various microbial components, mainly by polyI:C and flagellin, the ligands to TLR3 and TLR5, respectively in human corneal epithelium ex vivo and in vitro cultures. Pro-IL-33 protein was normally restricted inside cells, and could be secreted outside when activated by ATP. The PolyI:C induced IL-33 production was blocked by TLR3 antibody or TRIF Inhibitory peptide, while flagellin stimulated IL-33 was blocked by TLR5 antibody or MyD88 Inhibitory peptide. Interestingly, IκB-α inhibitor (BAY11-7082) or NF-κB inhibitor (quinazoline) blocked NF-κB p65 protein nuclear translocation, and suppressed IL-33 production induced by PolyI:C and flagellin. These findings demonstrate that IL-33, an epithelium-derived pro-allergic cytokine, is induced by microbial ligands through TLR-mediated innate signaling pathways, suggesting a possible role of mucosal epithelium in Th2-dominant allergic inflammation.

Keywords: Interleukin 33, toll-like receptor, NF-κB, Mucosal Immunity

INTRODUCTION

Mucosal epithelium functions not only as a physical barrier, but also as a regulator of innate and adaptive immune responses against foreign substances and microorganisms. In particular, epithelial cells have been directly implicated in T helper 2 (Th2) responses, serving as a critical interface between innate immunity and adaptive immune response [1, 2]. Recent studies have identified two novel epithelium-derived pro-allergic cytokines, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and interleukin (IL) 33, as key initiators of the adaptive Th2 response in allergic inflammatory diseases [3-7]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize conserved microbial components, are important pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and play an important role in the mucosal innate immune system [8]. They detect the presence and the nature of commensal and pathogenic microbes, thus providing the first line of host defense [9]. Functional TLRs 1-7 and TLR9 have been identified to be expressed in human ocular surface [10]. TLR activation by pathogens on the ocular surface would result in innate immune responses that stimulate production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as promote immune cell infiltration into the area to alleviate the microbial load and resolve the infection.

IL-33, a new member of the IL-1 super family, is produced mainly by epithelial and endothelial cells, fibroblast, and others [11-13]. IL-33 has been recently identified as a ligand for ST2, a protein encoded by IL-1 receptor-like 1 (IL-1RL1) gene, which is preferentially expressed by Th2 cells and is involved in allergic inflammation. By binding to ST2 receptor, IL-33 can activate Th2 cells and mast cells to secrete proinflammatory and Th2 cell-associated cytokines and chemokines that lead to severe pathological changes in mucosal organs [11]. IL-33 expression has been found to be up-regulated by stimulation with inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1β [14]. However, it is still unclear how IL-33 is induced by environmental allergens, and how microbial components play a role in initiating and developing allergic diseases.

In the present study, we investigated the TLR-mediated induction of IL-33 and the signaling pathway in human ocular surface mucosa that responses to microbial components using human corneal epithelial cells to explore the potential role of an innate immune response in Th2-dominant allergic inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Reagents

Cell culture dishes, plates, centrifuge tubes, and other plastic ware were purchased from BD Biosciences (Lincoln Park, NJ); polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane was from Millipore (Bedford, MA); polyacrylamide ready gels (4%–15% Tris-HCl), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), prestained SDS-PAGE low range standards, precision plus protein standards and precision protein Strep-Tactin horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA); Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Ham’s F-12, amphotericin B and gentamicin were from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY); and fetal bovine serum (FBS) from Hyclone (Logan, UT). The extracted or synthetic microbial components, Pam3CSK4, peptidoglycan from Bacillus subtilis (PGN-BS), flagellin from S. typhimurium, diacylated lipoprotein (FSL-1), imiquimod (R837), single-stranded GU-rich oligonucleotide complexed with LyoVec (ssRNA40/LyoVec), and type C CpG oligonucleotide (ODN 2395), MyD88 inhibitory peptide (Pepinh-MYD), TRIF inhibitory peptide (Pepinh-TRIF) and IκB-α inhibitor (BAY11-7082) were from invivoGen (Santiago, CA). Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Ab) against IL-33, TLR3, TLR5 and p65 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Human IL-33 ELISA DuoSet and affinity-purified goat Ab to IL-33 propeptide were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Monoclonal mouse antibodies (mAb) against IκBα, phospho-IκBα and ß-Actin were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). RNeasy Mini RNA extraction kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA); Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents and Ready-To-Go-Primer First-Strand Beads were obtained from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ); TaqMan gene expression assays and real-time PCR master mix were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA); and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and BCA protein assay kit from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL).

Primary Human Corneal Epithelial Culture Model for IL-33 Induction

Fresh human corneoscleral tissues from donors aged 19 to 67 years and in 72 hours post mortem were obtained from the Lions Eye Bank of Texas (Houston, TX). Human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) were cultured in 12-well plates with explants of corneal limbal rims in a supplemented hormonal epidermal medium (SHEM) containing 5% FBS according to our previously reported method [15]. Corneal epithelial cell growth was carefully monitored, and only the epithelial cultures without visible fibroblast contamination were used for this study. Confluent corneal epithelial cultures were switched to serum-free SHEM and treated for different periods (1, 4, 8, 16, 24, or 48 hours) with a series of microbial components in different concentrations. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. The cells treated for 1 to 24 hours were lysed for total RNA extraction and evaluating mRNA expression. The supernatants of the conditioned medium and the cell lysate in the cultures treated for 24-48 hours were collected and stored at −80°C for immunoassay.

Human Corneal Epithelial Tissue ex vivo Model for IL-33 Induction

A fresh corneoscleral tissue was cut into four equal-sized pieces. Each quarter of was placed into a well of an eight-chamber slide with epithelial side up in 150μL of serum-free SHEM medium, without or with polyI:C (50 μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) for 24 hours in a 37°C incubator. The corneal epithelial tissues were prepared for frozen sections for IL-33 immunohistochemical staining.

TLR and NF-κB Signaling Pathway Assays

HCECs were preincubated with specific TLR antibodies or pathway inhibitors, Pepinh-MYD (40μM), Pepinh-TRIF (40μM), BAY11-7082 (10μM) or NF-κB activation inhibitor (quinazoline 10μM) for 1-6 hour before polyI:C or flagellin was added for an additional 1, 4, 24, or 48 hours respectively. The cells in six-well plates were lysed for extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins with a nuclear extraction kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad CA), and stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis. The cells in eight-chamber slides were fixed for NF-κB p65 immunofluorescent staining. The cells in 12-well plates were subjected to total RNA extraction for measuring IL-33 expression by RT and real-time PCR. The cultured cells treated for 24-48 hours were lysed in RIPA buffer for IL-33 ELISA and Western blot analysis.

Total RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription (RT) and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using a Qiagen RNeasy® Mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and quantified by a NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer and stored at −80°C. The first strand cDNA was synthesized by RT from 1 μg of total RNA using Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads as previously described [16, 17]. The real-time PCR was performed in a Mx3005P™ system (Stratagene) with 20μl reaction volume containing 5μl of cDNA, 1μl of TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay for IL-33 (TaqMan Assay ID Hs00369211 m1) or GAPDH (Hs99999905 m1) and 10μl Master Mix. The thermocycler parameters were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. A non-template control was included to evaluate DNA contamination. The results were analyzed by the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method and normalized by GAPDH [17, 18].

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Double-sandwich ELISA for human IL-33 was performed, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, to determine the concentration of IL-33 protein in conditioned media and culture cell lysates from different treatments. Absorbance was read at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 570 nm by a VERSAmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescent Staining

Indirect immunostaining was performed according to our previously reported methods [15, 19, 20]. In brief, the human corneal frozen sections or corneal epithelial cells on eight chamber slides were fixed in acetone at −30°C for 5 minutes. Cell cultures were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 10 minutes. Primary rabbit antibodies against human IL-33 (1:100, 2 μg/mL) were applied for 1 hour. A goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (R&D Systems) and an ABC peroxidase system (Vectastain; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were then used for histochemical staining. For fluorescent staining, AlexaFluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody was applied for 1 hour followed by propidium iodide (PI, 2μg/mL) for 5 minutes for nuclear counterstaining. Secondary antibody alone or isotype IgG were used as the negative controls. The results were photographed with an epifluorescence microscope (Eclipse 400; Nikon, Garden City, NY) using a digital camera (DMX 1200; Nikon).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using a previously reported method [21]. Briefly, the cell lysate (50μg per lane, measured by a BCA protein assay kit) was mixed with 6×SDS reducing sample buffer and boiled for 5 minutes before loading. The proteins were separated on an SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred electronically to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TTBS (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.9% NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated, first with primary antibody against pro-IL-33 or NF-κB p65 overnight at 4°C, and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. The signal bands were detected with an ECL chemiluminescence reagent using a Kodak image station 2000R (Eastman Kodak, New Haven, CT).

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was used to compare differences between two groups. One-way ANOVA test was used to make comparisons among three or more groups, and the Dunnett’s post-hoc test was used to identify between group differences. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Induction of IL-33 in HCECs Exposed to Different Microbial Components

Primary HCECs were challenged by a variety of extracted or synthetic microbial components, representing the ligands respective to TLRs 1-9 for 4-48 hours. IL-33 expression at the mRNA and protein levels was evaluated by RT and real-time PCR and ELISA, respectively. The mRNA expression of IL-33 in untreated primary HCECs was at a relatively low level, but was largely induced (about 2-7 fold) after exposure to certain viral or bacterial components, including polyI:C, LPS, flagellin, FSL-1 and imiquimod (R837), which are the ligands to TLR3, -4, -5, -6 and -7, respectively (Figure 1A). IL-33 expression was not significantly induced by other bacterial components, such as the TLR1 ligand pam3csk4 (1–100 μg/mL), TLR2 ligands PGN-BS (1–50 μg/mL) and TLR9 ligand bacterial DNA unmethylated CpG motifs (CCpG-ODN, 1–50 μg/mL), as well as the TLR8 ligand virus single stranded RNA (ssRNA40, 0.1–10 μg/mL). A corresponding increase of IL-33 protein was detected by ELISA in whole cell lysates of HCECs exposed to these TLR ligands for 48 hours (Figure 1B). When compared with the untreated control (0.318±0.026 ng/mg cell protein), the IL-33 protein levels increased to 2.68±0.14, 1.20±0.15, 2.09±0.16, 1.94±0.17 and 1.13±0.35 ng/mg cell protein (P <0.01, n =4), respectively, in the primary HCECs exposed to PolyI:C (50μg/mL), LPS (10μg/mL), flagellin (10μg/mL), FSL-1 (10μg/mL) and R837 (10μg/mL), respectively. The expression of IL-33 mRNA was induced to peak levels at 8 hours in a concentration-dependent fashion by several microbial ligands, including polyI:C as shown in Figure 1C.

Figure 1.

TLR-dependent induction of IL-33 by microbial ligands in primary HCECs. A. Levels of IL-33 mRNA at 8 hours after stimulation by 50μg/ml polyI:C or 10μg/ml of Pam3CSK4, PGN, polyI:C, LPS, flagellin, FSL-1, R-837, ssRNA40 or C-CpG-ODN. B. The concentrations of IL-33 protein detected by ELISA in cell lysates treated with various TLR ligands (X-axis) for 48 hours. C. Levels of IL-33 mRNA at different time periods (4-24 h) in cells treated with 50μg/ml polyI:C (left), or by increasing concentration (10, 25, or 50μg/ml) of polyI:C at 8 hours (right), evaluated by quantitative RT and real-time PCR. Results shown are the mean ± SD of three to five independent experiments. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Release of IL-33 Cellular Protein to Culture Medium

Although we successfully detected the increased mRNA expression and cellular protein production of IL-33 in HCECs challenged by certain TLR ligands, no significant changes of IL-33 protein levels could be detected by ELISA in 24 or 48 hour supernatants of the HCECs without or with treatment by these TLR ligands (data not shown). Previously reported studies have found that IL-33 protein is not secreted from the cells unless it is activated, which usually implies that a cleavage step is required [22]. Interestingly, similar to these previous studies, our results showed that IL-33 protein could be released for secretion to the culture medium by adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP), which activates caspase-1 cleavage of IL-33 by triggering the P2X7 receptor (a cell-surface ATP receptor) [22]. As measured by ELISA, IL-33 concentration in the culture supernatant significantly increased from 38.1±3.46 pg/mL in the control group to 159.23±38.36 or 213.7±38.99 pg/mL, respectively, in HCECs exposed to PolyI:C (50μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) for 48 hours with additional incubation with ATP for the last 30 min. In contrast, the protein levels of IL-33 in the culture supernatants were 70.19±9.59 and 64.63±12.79 pg/mL, respectively, in HCECs treated by PolyI:C or flagellin without ATP. It appeared that the ATP co-incubation in the last 30 min largely contributed to the secretion of IL-33 (3-5 fold) in PolyI:C or flagellin treated groups when compared with the untreated controls without or with ATP co-incubation (Figure 2, A & B).

Figure 2.

Stimulated secretion of IL-33 cellular protein to culture medium by ATP in primary HCECs. The HCECs were exposed to microbial ligand 50μg/ml polyI:C (A, C, E, G) or 10μg/ml flagellin (B, D, F, H) for 48 hours without or with addition of 5mM ATP to media 30min prior to measurement. The IL-33 protein concentrations in culture media (A & B) and in cell lysates were detected by ELISA (C & D), and the level of cellular IL-33 protein was also evaluated by Western blot analysis using β-actin as control (E & F) with quantitative ratio of IL-33/β-actin (G & H). Results shown are the mean ± SD of three to five independent experiments. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Interestingly, the stimulatory effect of ATP on IL-33 release was confirmed by a corresponding change in IL-33 cellular protein levels. As shown in Figures 2C and 2D, the cellular IL-33 protein level was stimulated by polyI:C or flagellin, while it markedly decreased ( 3-5 fold, P <0.01, n =4, respectively) after co-incubation with ATP for 30 minutes. Western blot bands (Figure 2 E & F) and quantitative analysis of IL-33 (Figure 2 G & H) normalized by β-actin control further confirmed the stimulation effect of ATP on release of IL-33 from cells induced by two TLR ligands, polyI:C or flagellin, respectively.

Induction of IL-33 in an ex vivo Model of Human Corneal Tissues

To further investigate the cellular location and stimulation of IL-33 protein ex vivo, fresh human corneal tissues were incubated ex vivo with polyI:C or flagellin for 48 hours. Immunohistochemical staining showed that IL-33 protein was normally produced by certain basal epithelial cells, and mainly located in the nucleus and cytoplasm in the untreated corneal epithelial tissues. Stronger staining throughout multiple layers of corneal epithelium was observed in the tissues exposed to polyI:C (50μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) for 48 hours (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

IL-33 induction in an ex vivo human corneal tissues evaluated by immunohistochemical staining. A fresh corneoscleral tissue was cut into four equal-sized pieces. Each quarter was placed into a well of eight-chamber slides, epithelial side up in 150μL of serum-free SHEM medium, without or with polyI:C (50μg/ml) or flagellin (10μg/ml) for 24 hours in a 37°C incubator. Frozen sections of corneal tissues were used for IL-33 immunohistochemical staining with isotype IgG as the negative control. Magnification 400x.

TLR and NF-κB Signaling Pathways Involved in IL-33 Induction

Since IL-33 showed the greatest induction in response to synthetic dsRNA polyI:C and extracted bacterial flaggelin, we further investigated the signaling pathways that mediated the IL-33 induction. When HCECs were pre-incubated with a rabbit antibody against TLR3 or TLR5 (10μg/mL) one hour before challenged by TLR3 ligand polyI:C (50μg/mL) or TLR5 ligand flaggelin, respectively, for 8 or 48 hours, the stimulated induction of IL-33 transcript (Figure 4, A & B) and protein (Figure 4 C-H) by these two microbial components was dramatically reduced. Following TLR activation by its ligand, the signaling pathways are mainly initiated via two different adaptor proteins, myeloid differentiation factor-88 (MyD88) and TIR-domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon β (TRIF) [10, 23]. To study which adaptor signaling was activated by polyI:C or flaggelin during IL-33 induction, the HCECs were preincubated with MyD88 inhibitory peptide (Pepinh-MYD) or TRIF inhibitory peptide (Pepinh-TRIF) for 6h. We observed that the stimulated levels of IL-33 mRNA and cellular protein by polyI:C were largely blocked by Pepinh-TRIF (P< 0.01, n=4), but not by Pepinh-MYD (Figure 4 A, C, E & G). In contrast, flagellin stimulated IL-33 mRNA and protein levels were significantly inhibited by Pepinh-MYD (P< 0.05, n=4), but not by Pepinh-TRIF, as shown in Figure 4 B, D, F and H. TLR signaling typically induces activation of the transcription nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). Preincubation with an IκB-α inhibitor BAY11-7082 or a NF-κB activation inhibitor quinazoline (NF-κB-I) for 1h was found to significantly block the stimulated expression and production of IL-33 by HCECs exposed to these 2 TLR ligands (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

TLR and NF-κB signaling pathways are involved in IL-33 induction by polyI:C or flagellin. The HCECs exposed to polyI:C (50μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) were preincubated in the absence or presence of rabbit TLR3Ab (10μg/mL), TLR5Ab (10μg/mL), BAY11-7082 (10μM) or NF-kB activation inhibitor quinazoline (NF-kB-I, 10μM) for 1 hour, and Pepinh-MYD (40μM) or Pepinh-TRIF (40μM) for 6 hours. The cultures treated by ligands for 8 hours were subjected to RT and real-time PCR to measure IL-33 mRNA (A & B), the cultures treated for 48 hours were used to evaluate IL-33 protein in cell lysates by ELISA (C & D) and Western blot using β-actin as control (E & F) with quantitative ratio of IL-33/β-actin (G & H).. Results shown are the mean ± SD of three to five independent experiments. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

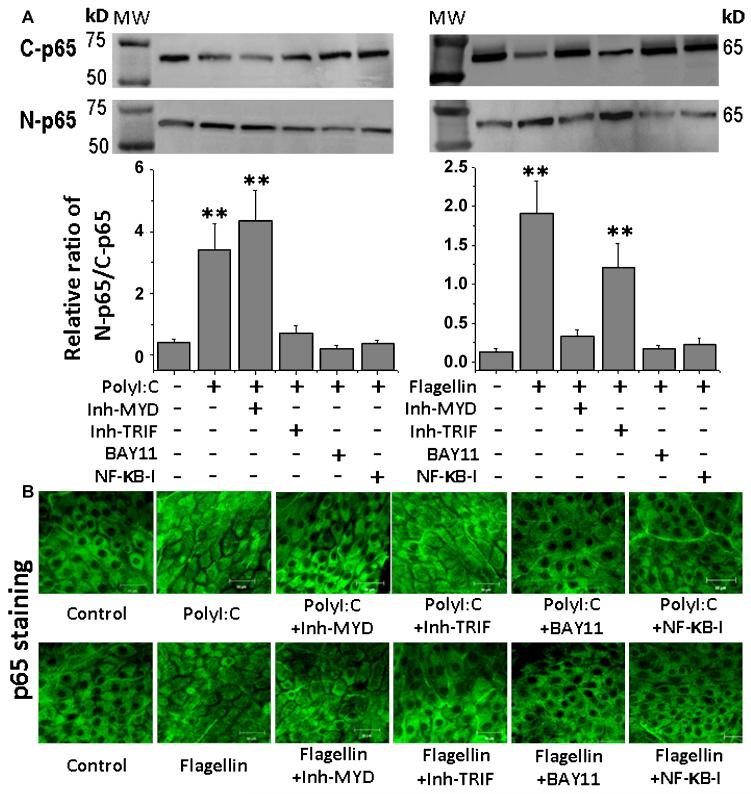

Western blot analysis further confirmed the involvement of these signaling pathways (Figure 5 & 6). When Pepinh-TRIF and Pepinh-MYD respectively blocked the expression and production of IL-33 stimulated by polyI:C or flagellin, they also greatly suppressed the stimulated IκB-α phosphorylation (A & C, B & D) and degradation (A & E, B & F), as well as NF-κB activation with p65 protein nuclear translocation (Figure 6A). Preincubation with BAY11-7082 or NF-κB-I significantly suppressed the IκB-α, phosphorylation and degradation, as well as NF-κB p65 nulear translocation stimulated by these two TLR ligands. As further confirmation, immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that the NF-κB p65 protein translocated from cytoplasm to nucleus in corneal epithelial cells exposed to polyI:C or flagellin for 4 hours. This NF-κB activation with p65 nuclear translocation was largely blocked by preincubation with Pepinh-TRIF, Pepinh-MYD, BAY11-7082 or NF-κB-I (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Activation of IkBα signaling induced by polyI:C and flagellin in HCECs. The HCECs were exposed to polyI:C (50μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) in the absence or presence of preincubated Pepinh-MYD (40μM) or Pepinh-TRIF (40μM) for 6 hours, and BAY11-7082 (10μM) or NF-kB activation inhibitor quinazoline (NF-kB-I, 10μM) for 1 hour. The cells treated for 1 hour were used for IκB-α phosphorylation (A & C, B & D) and degradation (A & E, B & F) with β-actin as control by Western blotting and quantitative ratio analysis of p-IkB-α/β-actin (C & D) or IkB-α/β-actin (E & F). Results shown are the mean ± SD of three to five independent experiments. *P< 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Activation of NF-κB signaling induced by polyI:C and flagellin in HCECs. A. The HCECs were exposed to polyI:C (50μg/mL) or flagellin (10μg/mL) in the absence or presence of preincubated Pepinh-MYD (40μM) or Pepinh-TRIF (40μM) for 6 hours, and BAY11-7082 (10μM) or NF-kB activation inhibitor quinazoline (NF-kB-I, 10μM) for 1 hour. The cells treated for 4 hours were subjected to cytoplasm and nuclear protein extraction for NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation analysis by Western blotting with quantitative ratio analysis of N-p65/C-p65. Results shown are the mean ± SD of three to five independent experiments. **P < 0.01. C-p65, cytoplasm p65; N-p65, nuclear p65. B. The cells treated for 4 hours in 8-chamber slides were fixed in acetone for immunofluorescent staining with rabbit antibody against p65 followed by AlexaFluor 488-conjugated second antibody. The images are representatives from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have provided compelling evidence that in addition to physical barrier function, epithelial cells actively participate, as initiators, mediators and regulators, in innate and adaptive immune responses for host defense [24]. A novel proallergic cytokine IL-33, which was found to be mainly produced by mucosal epithelia, has been recently identified as a natural ligand of the IL-1 receptor family member ST2, which has been well known to enhance experimental allergic inflammatory responses by costimulating the production of cytokines from activated Th2 lymphocytes [25]. However, the regulated expression of IL-33 by mucosal surface epithelia has not been well investigated. Using fresh donor corneal tissues and primary human corneal epithelial cells, the present study revealed that IL-33 is expressed by normal corneal epithelium and is largely induced by microbial components through TLR and NF-κB signaling pathways. Our findings suggest that stimulated production of the mucosal epithelial cell-derived cytokine IL-33 by innate immunity signaling pathway could participate in allergic inflammatory diseases.

TLR-dependent Induction of IL-33 by HCECs in Response to Microbial Components

The discovery of TLRs, the most important family among the PRRs, represented a breakthrough in understanding regarding ability of the innate immune system to rapidly recognize pathogens. At least 11 human TLRs have been identified to date. Each TLR has unique ligand specificity. In general, TLR1, -2, -4, -5, and -6 are present on the cell plasma membrane and respond to a variety of bacterial and fungal components, whereas TLR3, -7, -8, and -9 are mainly present on endosomal membranes inside cells and recognize virus nucleic acids. Recently, TLR3 was also found to be present on cell surface in human endothelial and corneal epithelial cells. TLRs are expressed on immune cells that are most likely to first encounter microbes, such as neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. In addition to innate immune cells, an array of TLRs is expressed by epithelial cells at host/environment interfaces, including the skin, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract and ocular surface. HCECs have been shown to express functional TLRs 1-9 except for TLR8, and to be able to recognize the presence of viral and bacterial components, and initiate innate immune responses through production of proinflammatory cytokines. In this study, we have evaluated the induction of IL-33 by HCECs in response to 9 extracted or synthetic microbial components that are ligands of TLRs 1-9.

As shown in Figure 1, the expression and production of proallergic cytokine IL-33 was largely induced by polyI:C, LPS, flagellin, FSL-1 and R837, the ligands for TLR3, -4, -5, -6 and -7, representing viral dsRNA and the bacterial components flagellin and lipopeptides, respectively. PolyI:C and flagellin were the most robust IL-33 inducers, stimulating IL-33 production by 7- and 4-fold, respectively, with peak mRNA levels noted at 8 hours in HCECs. The IL-33 induction by these 2 ligands was further confirmed using an ex vivo donor corneal tissue model (Figure 3). The specificity of the TLR-dependent response by HCECs was also confirmed by demonstrating significant inhibition of polyI:C or flagellin stimulated IL-33 expression following treatment with TLR3 or TLR5 antibodies, respectively (Figure 4). The pattern of TLR-dependent IL-33 induction indicates that HCECs are able to rapidly initiate an innate immune response to virus or bacteria, and play an important role in allergic inflammatory disease.

The Potential Mechanism Involved in IL-33 Secretion and Activation

As a member of IL-1 super family, IL-33 functions as an extracellular inflammatory cytokine, while it also acts as a nuclear transcription factor. It has been shown that IL-33 is mainly localized to the nucleus of endothelial cells where it is bound to chromatin [26]. IL-33 mRNA is primarily translated and synthesized in vivo as a 30-kDa precursor, pro-IL-33 protein. Like IL-1 and IL-18, pro-IL-33 protein sequence lacks a signal peptide that directs its secretion via the ER–Golgi pathway [11, 27]. Like pro-IL-1β, human pro-IL-33 was reported to be cleaved by caspase-1 to generate an 18-kDa active form that is sufficient to activate signaling via the IL-33 receptor ST2. Recombinant mature IL-33 has been known to induce Th2-associated cytokines and inflammatory cytokines via its receptor, ST2 [27, 28]. However, processing of pro-IL-33 in vivo has not been clarified yet. It is not clear whether caspase-1 cleavage of pro-IL-33 occurs in vivo, and whether, as for IL-1β, this cleavage is a prerequisite for IL-33 secretion and bioactivity. IL-33 was reported to be active as full length protein (pro-IL33) while to be inactivated by caspase-1 cleavage [28], which is under debate.

Our data showed that no significantly changes of IL-33 protein levels detected by ELISA in the culture supernatants of the stimulated HCECs. As shown in Figure 2, the IL-33 protein levels significantly increased in the cell lysate, but not in the culture supernatants, of HCECs exposed to poly I:C or flagellin, when compared with the untreated control. However, the stimulated cellular IL-33 protein was released into the culture supernatant after co-incubation with ATP for 30 minutes, as evaluated by ELISA and Western blot analysis. Our finding supports a notion that caspase 1-dependant activation may be involved in the release and secretion of IL-33 protein because ATP has been known to activate caspase-1 through triggering the P2X7 receptor [22]. Further studies are necessary to clarify this underlying mechanism.

TLR/NF-κB Signaling Mediating Innate Immune Response for IL-33 Induction

TLRs, capable of recognizing conserved microbial components, control host innate responses to mucosal and systemic infections. Signaling involves the intracellular Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain. Following ligand binding, TLR signaling is initiated by the recruitment of adaptor proteins to the TIR domain, including MyD88, MyD88 adapter-like protein (Mal), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) and the sterile α- and armadillo-motif-containing protein (SARM) [29, 30]. MyD88 is a universal adapter protein as it is used by all TLRs except TLR3. MyD88 transduces signal through IRAK (IL-1R-associated kinase) and TRAF6 (tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor), leading to the activation of transcription factor NF-κB [31, 32]. Most of the TLRs seem to be absolutely dependent on the expression of MyD88 for all of their functions, except TLR3 and TLR4 that have a unique ability to activate MyD88-independent antiviral responses by a mechanism involving the activation of IRF3. MyD88-independent signaling events are controlled by TRIF (for TLR3) or TRIF/TRAM (for TLR4) and induce IRF3-dependent type I interferon production (see review articles [10, 22]).

Our data showed that synthetic dsRNA polyI:C-induced IL-33 expression and production were markedly blocked by TLR3 antibody and Pepinh-TRIF, but not by Pepinh-MyD88, while extracted bacterial component flagellin-induced IL-33 production was dramatically suppressed by TLR5 antibody and Pepinh-MyD88, but not by Pepinh-TRIF, in corneal epithelial cells. These findings indicate that the induction of the proallergic cytokine IL-33 is triggered by specific TLR ligands through innate signaling pathways in mucosal epithelia.

Although the recognition of different ligands by specific TLRs leads to activation of an intracellular signaling cascade in a MyD88 dependent or independent fashion, all TLRs share NF-κB signal transduction pathways for activation of the transcription factors [10, 22]. NF-κB is present in the cytoplasm of resting cells as a dimer bound to an inhibitor protein (IκB) to form an inactive protein complex. Thus NF-κB biological activity is controlled mainly by the IkB alpha and IkB beta proteins, which restrict NF-κB to the cytoplasm and inhibit its DNA binding activity. Phosphorylation of IκB, which leads to its dissociation from NF-κB protein and subsequent degradation, results in the release and translocation of NF-κB protein from cytoplasm to nucleus, which triggers transcription of IL-33 and relevant inflammatory genes.

We have previously demonstrated that TSLP, another epithelium-derived pro-allergic cytokine, is induced by an innate immune response of ocular mucosal epithelium through TLR/NF-κB signaling pathways. The present study has shown that NF-κB was dramatically activated with p65 protein nuclear translocation in corneal epithelial cells exposed to polyI:C or flagellin for 4 hours, demonstrated by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescent staining (Figures 5, 6). BAY 11, a selective inhibitor of IκB-α phosphorylation and degradation, blocked the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 protein. NF-κB activation inhibitor quinazoline also blocked p65 nuclear translocation. Interestingly, the stimulated induction of IL-33 by polyI:C or flagellin were also markedly blocked by these NF-κB activation inhibitors. These findings confirmed that IL-33 induction in HCECs is mediated by the TLR and NF-κB signaling pathways.

In summary, this study demonstrates a novel phenomenon that a newly defined pro-allergic cytokine IL-33 is largely induced by microbial components through TLR and NF-κB signaling pathways in human corneal epithelium. Our findings suggest that human ocular mucosal epithelium plays an important role in initiating Th2-dominant allergic inflammation via innate immune responses. Furthermore, IL-33 and TLRs could become novel molecular targets for the intervention of allergic inflammatory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Department of Defense CDMRP PRMRP grant FY06 PR064719 (DQL), National Institutes of Health grant EY11915 (SCP), an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, the Oshman Foundation and the William Stamps Farish Fund.

Footnotes

Commercial relationship: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Holgate ST. The epithelium takes centre stage in asthma and atopic dermatitis. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bulek K, Swaidani S, Aronica M, Li X. Epithelium: the interplay between innate and Th2 immunity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liu YJ, Soumelis V, Watanabe N, Ito T, Wang YH, Malefyt RW, Omori M, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. TSLP: an epithelial cell cytokine that regulates T cell differentiation by conditioning dendritic cell maturation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:193–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liu YJ. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and OX40 ligand pathway in the initiation of dendritic cell-mediated allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Demehri S, Morimoto M, Holtzman MJ, Kopan R. Skin-derived TSLP triggers progression from epidermal-barrier defects to asthma. PLoS. Biol. 2009;7:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matsuda A, Okayama Y, Terai N, Yokoi N, Ebihara N, Tanioka H, Kawasaki S, Inatomi T, Katoh N, Ueda E, Hamuro J, Murakami A, Kinoshita S. The role of interleukin-33 in chronic allergic conjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:4646–4652. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kearley J, Buckland KF, Mathie SA, Lloyd CM. Resolution of allergic inflammation and airway hyperreactivity is dependent upon disruption of the T1/ST2-IL-33 pathway. Am. J Respir. Crit Care Med. 2009;179:772–781. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-666OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Alexopoulou L, Kontoyiannis D. Contribution of microbial-associated molecules in innate mucosal responses. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1349–1358. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mayer AK, Muehmer M, Mages J, Gueinzius K, Hess C, Heeg K, Bals R, Lang R, Dalpke AH. Differential recognition of TLR-dependent microbial ligands in human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3134–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kumar A, Yu FS. Toll-like receptors and corneal innate immunity. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006;6:327–337. doi: 10.2174/156652406776894572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS. One. 2008;3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smith DE. IL-33: a tissue derived cytokine pathway involved in allergic inflammation and asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Allam JP, Bieber T, Novak N. Dendritic cells as potential targets for mucosal immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;9:554–557. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833239a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim HS, Jun S, X, de Paiva CS, Chen Z, Pflugfelder SC, Li D-Q. Phenotypic characterization of human corneal epithelial cells expanded ex vivo from limbal explant and single cell cultures. Exp. Eye Res. 2004;79:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Luo L, Li D-Q, Doshi A, Farley W, Corrales RM, Pflugfelder SC. Experimental dry eye stimulates production of inflammatory cytokines and MMP-9 and activates MAPK signaling pathways on the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis. Sci. 2004;45:4293–4301. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yoon KC, de Paiva CS, Qi H, Chen Z, Farley WJ, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC. Expression of Th-1 chemokines and chemokine receptors on the ocular surface of C57BL/6 mice: effects of desiccating stress. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:2561–2569. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Paiva CS, Corrales RM, Villarreal AL, Farley WJ, Li D-Q, Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC. Corticosteroid and doxycycline suppress MMP-9 and inflammatory cytokine expression, MAPK activation in the corneal epithelium in experimental dry eye. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;83:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li D-Q, Tseng SC. Three patterns of cytokine expression potentially involved in epithelial-fibroblast interactions of human ocular surface. J. Cell Physiol. 1995;163:61–79. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen Z, de Paiva CS, Luo L, Kretzer FL, Pflugfelder SC, Li D-Q. Characterization of putative stem cell phenotype in human limbal epithelia. Stem Cells. 2004;22:355–366. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li D-Q, Luo L, Chen Z, Kim HS, Song XJ, Pflugfelder SC. JNK and ERK MAP kinases mediate induction of IL-1beta, TNF-alpha and IL-8 following hyperosmolar stress in human limbal epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Krishnan J, Selvarajoo K, Tsuchiya M, Lee G, Choi S. Toll-like receptor signal transduction. Exp. Mol. Med. 2007;39:421–438. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brikos C, O’Neill LA. Signalling of toll-like receptors. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2008:21–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hoebe K, Janssen E, Beutler B. The interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:971–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1004-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Allakhverdi Z, Smith DE, Comeau MR, Delespesse G. Cutting edge: The ST2 ligand IL-33 potently activates and drives maturation of human mast cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:2051–2054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Haraldsen G, Balogh J, Pollheimer J, Sponheim J, Kuchler AM. Interleukin-33 -cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hayakawa M, Hayakawa H, Matsuyama Y, Tamemoto H, Okazaki H, Tominaga S. Mature interleukin-33 is produced by calpain-mediated cleavage in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;387:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Talabot-Ayer D, Lamacchia C, Gabay C, Palmer G. Interleukin-33 is biologically active independently of caspase-1 cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:19420–19426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].O’Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Johnson AC, Heinzel FP, Diaconu E, Sun Y, Hise AG, Golenbock D, Lass JH, Pearlman E. Activation of toll-like receptor (TLR)2, TLR4, and TLR9 in the mammalian cornea induces MyD88-dependent corneal inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:589–595. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Figueiredo MD, Vandenplas ML, Hurley DJ, Moore JN. Differential induction of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways in equine monocytes by Toll-like receptor agonists. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]