Abstract

Rationale: Treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been shown to be associated with an increased incidence of pneumonia. However, it is unclear if this is associated with increased mortality.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to examine the effects of prior use of ICS on clinical outcomes for patients with COPD hospitalized with pneumonia.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the national administrative databases of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Eligible patients had a preexisting diagnosis of COPD, had a discharge diagnosis of pneumonia, and received treatment with one or more appropriate pulmonary medications before hospitalization. Outcomes included mortality, use of invasive mechanical ventilation, and vasopressor use.

Measurements and Main Results: There were 15,768 patients (8,271 with use of ICS and 7,497 with no use of ICS) with COPD who were hospitalized for pneumonia. There was also a significant difference for 90-day mortality (ICS 17.3% vs. no ICS 22.8%; P < 0.001). Multilevel regression analyses demonstrated that prior receipt of ICS was associated with decreased mortality at 30 days (odds ratio [OR] 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.89) and 90 days (OR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.72–0.85), and decreased use of mechanical ventilation (OR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72–0.94). There was no significant association between receipt of ICS and vasopressor use (OR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74–1.04).

Conclusions: For patients with COPD, prior use of ICS is independently associated with decreased risk of short-term mortality and use of mechanical ventilation after hospitalization for pneumonia.

Keywords: inhaled corticosteroids, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mortality

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Studies demonstrate that use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increases the incidence of pneumonia. However, it is unclear if this use leads to worse outcomes.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our study demonstrates no significant associations between inhaled corticosteroids use and clinical outcomes for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who do develop pneumonia.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth most frequent cause of chronic morbidity and mortality in developed countries (1). One of the current recommended COPD treatments by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) is inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for symptomatic patients with a documented bronchodilator response on spirometry or for patients with FEV1 less than 50% predicted, which is indicative of moderate-to-severe COPD (2). Although ICS treatment reduces the overall frequency of exacerbations of COPD (3), evidence suggests that ICS treatment is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia (4–6).

Despite several studies demonstrating that patients with COPD have an increased likelihood of developing pneumonia when receiving ICS (4–8), it remains unclear if use of ICS is associated with adverse medical outcomes for patients with COPD. Prior studies examining the effect of COPD on pneumonia-related mortality have led to conflicting conclusions (9–11). Two systematic reviews examining the use of ICS therapy to manage COPD found no significant differences in mortality (4, 5). Another study comparing COPD exacerbation rates between patients being treated with either salmeterol or a combination of salmeterol and fluticasone demonstrated that all-cause mortality was similar for patients hospitalized with pneumonia regardless of prior use of ICS (6). However, they did find increased mortality for users of ICS with pneumonia within 30 days of hospitalization. Another recent study showed that use of ICS was associated with lower 30- and 90-day mortality after pneumonia; however, this study was not able to examine other clinically relevant outcomes or assess the effects of other appropriate respiratory medications received (12).

The aim of our study was to examine the association between prior use of ICS and clinical outcomes, including mortality, need for mechanical ventilation, and vasopressors, in patients with COPD hospitalized with pneumonia. Our hypothesis was that prior use of ICS would not be associated with worse clinical outcomes for patients with COPD hospitalized for pneumonia, after adjusting for potential confounders.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the national administrative databases of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System to examine treatments and outcomes for elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia. The VA databases are the repositories of clinical and administrative data from the more than 150 VA hospitals and 850 clinics (13). The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, approved this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We identified all patients who had a VA hospital stay during fiscal years 2002–2007 (October 2001 to September 2007) with a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision [ICD-9] codes 480.0–483.99 or 485–487.0) or a secondary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia with a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure (ICD-9 code 518.81) or sepsis (ICD-9 code 038.xx) (14–16). We included patients in this study if they (1) were 65 or older on the date of hospital presentation; (2) had at least 1 year of VA outpatient care before admission; (3) had received at least one dose of antibiotics within 48 hours of admission; and (4) had a prior diagnosis of COPD (ICD-9 codes 490–492,496) with use of at least one of the following respiratory medications during the 30-day period before hospitalization: any form of β-agonist, theophylline, tiotropium, or ipratropium bromide. For patients with multiple hospitalizations, we only assessed the first admission during the study period.

We excluded patients with history of asthma (ICD-9 codes 493.xx) and those who were treated with outpatient oral corticosteroids within 90-days before hospital admission.

Data

This study used demographic, utilization, and clinical data from the National Patient Care Database, pharmacy data from the VA Decision Support System and Pharmacy Benefits Management group, and mortality data from the VA vital status file. Encrypted patient identifiers were used to link the information from each database.

We obtained demographic information (age, sex, race, and marital status) from inpatient and outpatient data files. We categorized race as white, black, other, and missing. We used ICD-9 codes for tobacco use (305.1, V15.82), attendance at a smoking cessation clinic, or use of medications for the treatment of nicotine dependence (Zyban, nicotine replacement, or varenicline) to identify recent tobacco use. We used information on the VA means test as a surrogate for income.

We assessed the presence of comorbid conditions using data from inpatient and outpatient administrative data using the Charlson-Deyo system to assign comorbidity scores for preexisting conditions (17–19). The Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score is based on 19 comorbid conditions, each of which has an associated prognostic weight ranging from one to six.

The primary independent variable of interest was the prior use of ICS. We defined patients as current users of a given medication if they received a prescription within 90 days of the date of hospitalization. We classified the following medications as ICS: inhaled forms of triamcinolone, fluticasone, budesonide, beclamethasone, and flunisolide.

To control further for potential confounding, we calculated each patient's count of unique drugs in each of the following classes for drugs filled or refilled within 90 days of presentation: cardiac medications; respiratory medications (other than ICS); and diabetic medications. Previous research has demonstrated that using the count of these medication classes is preferable to adjusting for the individual medications (20).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for this study were 30- and 90-day mortality. We chose these time periods for follow-up because previous research demonstrated that mortality within 30-days is primarily pneumonia-related, whereas mortality between 60 and 90 days is more frequently caused by comorbid conditions (21). Mortality was assessed through January 1, 2008, using the VA vital status file. Previous studies have demonstrated that this data source has a sensitivity of approximately 98% for veterans’ deaths (22). Secondary outcomes were use of invasive mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support during hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

We used bivariate statistics to test the associations of demographic and clinical characteristics and mortality. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analyzed using Student t test. Because of the large sample size, we defined statistical significance using a two-tailed P less than 0.01.

For our primary analyses, we used generalized linear mixed-effect models with the patient's hospital as a random effect. We created separate models for each of the outcomes of interest, with use of ICS and potential confounders as the independent variables. We included variables as potential confounders in the models if we hypothesized a priori that they would be associated with the severity of COPD or the outcome of interest. Potential confounders included in the models of mortality were age, gender, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, number of primary care visits within 1 year before admission, classes of medications, nursing home status, current tobacco use, the Charlson composite score, intensive care unit admission, and receipt of guideline concordant antibiotics (23). Classes of medications were cardiac, diabetic, and other respiratory drugs. In addition, we determined the most common respiratory medicine regimes and then repeated our primary analyses including only patients who received those regimes ± ICS (e.g., for the short-acting β agonist [SABA] plus ipratropium group we included only patients who used SABA plus ipratropium ± ICS but no other respiratory medications).

To analyze time-to-death for patients by receipt of ICS, we used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate and graph the baseline survivor functions after adjusting for the potential confounders used in the mortality analyses.

All analyses were performed using STATA 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

In the entire VA system, during the study period of fiscal years 2002–2007, there were 962,408 admissions for those greater than 65 years of age of which 66,531 were for pneumonia. A total of 15,768 patients admitted to 122 VA hospitals met all study eligibility criteria. Of these, 8,271 (52.5%) patients received ICS and 7,497 (47.5%) did not receive ICS within 90 days of presentation. Among users of ICS, the most commonly prescribed medications were flunisolide (51.2% of all ICS prescribed); fluticasone (27.8%); and triamcinolone (19.8%). In the cohort, 98.4% of all patients were male; mean age was 76.5 years (standard deviation, 6.4 yr); and 52.5% were married. Comparisons of patient characteristics stratified by prior use of ICS revealed few clinically significant differences between the two groups (Table 1). Patients with use of ICS were less likely to have cancer or current tobacco use, and were more likely to be married, receiving long-acting β agonist or tiotropium therapy.

TABLE 1.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS BY THE USE OF OUTPATIENT INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

| Inhaled Corticosteroids Used Before Hospitalization |

|||

| Variable | Yes (n = 8,271) (%) | No (n = 7,497) (%) | P Value |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 76.3 (6.32) | 76.8 (6.46) | <0.001 |

| Male | 8,142 (98.4) | 7,375 (98.4) | 0.74 |

| Race | |||

| White | 7,262 (87.8) | 6,424 (85.7) | |

| Black | 642 (7.8) | 741 (9.9) | |

| Other | 76 (0.9) | 77 (1) | |

| Missing | 291 (3.5) | 255 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Married | 4,549 (53.7) | 3,930 (46.4) | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 3,947 (47.7) | 3,776 (50.4) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 346 (4.2) | 401 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Drug abuse | 98 (1.2) | 109 (1.5) | 0.14 |

| Preexisting comorbid conditions | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 2,468 (29.8) | 2,308 (30.8) | 0.20 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 1,337 (16.2) | 1,291 (17.2) | 0.08 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 82 (1) | 102 (1.4) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 2,345 (28.4) | 2,121 (28.3) | 0.93 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 652 (7.9) | 586 (7.8) | 0.88 |

| Renal disease | 870 (10.5) | 874 (11.7) | 0.02 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 19 (0.2) | 25 (0.3) | 0.22 |

| Mild liver disease | 60 (0.7) | 58 (0.8) | 0.73 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 311 (3.8) | 268 (3.6) | 0.54 |

| AIDS | 15 (0.2) | 9 (0.1) | 0.32 |

| Metastatic cancer | 261 (3.2) | 328 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 2,038 (24.6) | 2,047 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Leukemia | 151 (1.8) | 147 (2) | 0.53 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis and collagen vascular diseases | 163 (2) | 149 (2) | 0.94 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,258 (15.2) | 1,258 (16.8) | 0.007 |

| Myocardial infarction | 592 (7.2) | 588 (7.8) | 0.10 |

| Dementia | 247 (3.3) | 162 (2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes medications, mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.49) | 0.18 (0.48) | 0.23 |

| Cardiovascular medications, mean (SD) | 1.30 (1.41) | 1.49 (1.39) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory medications | |||

| Ipratropium | 5,646 (68.3) | 5,291 (70.6) | 0.002 |

| Long-acting β-agonists | 1,952 (23.6) | 671 (9) | <0.001 |

| Tiotroprium | 406 (4.9) | 131 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Theophylline | 898 (10.8) | 626 (8.4) | <0.001 |

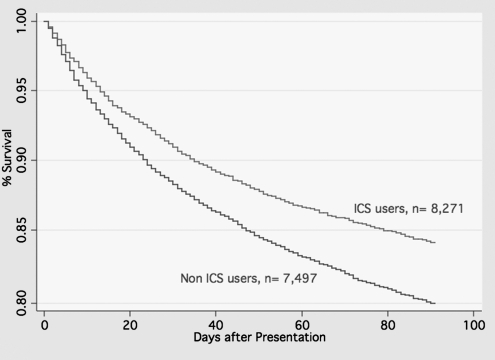

For this cohort, 1,859 (11.8%) patients died within 30 days, and 3,139 (19.9%) patients died within 90 days (Figure 1). Table 2 shows outcomes by use of ICS. There were significant differences in both 30- (users of ICS 10.2% vs. nonusers 13.6%; P < 0.001) and 90-day mortality (users of ICS 17.3% vs. nonusers 22.8%; P < 0.001). Patients who received ICS were significantly less likely to need mechanical ventilation (users of ICS 5.9% vs. nonusers 7.3%; P = 0.001), but there was no significant difference in the need for vasopressors.

Figure 1.

Survival curves for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalized with pneumonia by use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) versus nonuse (P < 0.0001) after adjusting for potential confounders.

TABLE 2.

UNIVARIATE OUTCOMES BY THE PRIOR RECEIPT OF ICS

| ICS Use Before Hospitalization |

|||

| Variable | Yes (n = 8,271) (%) | No (n = 7,497) (%) | P Value |

| 30-d mortality | 841 (10.2) | 1,018 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| 90-d mortality | 1,430 (17.3) | 1,709 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 491 (5.9) | 544 (7.3) | 0.001 |

| Vasopressors | 302 (3.7) | 318 (4.2) | 0.06 |

Definition of abbreviation: ICS = inhaled corticosteroids.

In the multilevel regression analyses (Table 3), after adjusting for potential confounders, prior receipt of ICS was associated with decreased 30- (odds ratio [OR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.89) and 90-day mortality (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.72–0.85). In addition, patients who had received ICS were less likely to require invasive mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.72–0.94) but there was no significant association with need for vasopressors (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74–1.04.) When we excluded those patients with cancer we found similar results: 30-day mortality (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68–0.82); 90-day mortality (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.73–0.85); mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.82–1.08); and vasopressors (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78–1.07.)

TABLE 3.

RESULTS OF MULTILEVEL REGRESSION MODELS AFTER ADJUSTING FOR POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS*

| Outcome | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

| 30-d mortality | 0.80 | 0.72–0.89 |

| 90-d mortality | 0.78 | 0.72–0.85 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.83 | 0.72–0.94 |

| Vasopressors | 0.88 | 0.74–1.04 |

After adjusting for age, sex, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, classes of medications, nursing home status, current tobacco use, Charlson composite score, intensive care unit admission, and receipt of guideline-concordant antibiotics.

We then restricted the multilevel models to patients who received the two most common combinations of respiratory medications (Table 4), with the reference group being those not receiving ICS, to determine the impact of other pulmonary medications. For the group that received SABA and ipratropium ± ICS (total n = 11,696), use of ICS was not significantly associated with worsening of any of the clinical outcomes, and receipt of ICS was associated with improved 90-day mortality, and less need for mechanical ventilation, but not 30-day mortality or use of vasopressor. For those who received SABA, ipratropium, and a long-acting β-agonist ± ICS (total n = 1,851) there were no significant associations with the outcomes of interest.

TABLE 4.

RESULTS OF MULTILEVEL REGRESSION ANALYSES BY THE MOST COMMON PULMONARY MEDICATIONS RECEIVED*

| Clinical Outcomes Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

||||

| Pulmonary medications prescribed | 30-Day Mortality | 90-Day Mortality | MV | Vasopressors |

| SABA + IPRA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SABA + IPRA + ICS | 0.82 (0.67–1) | 0.78 (0.66–0.93) | 0.64 (0.48–0.86) | 0.80 (0.57–1.13) |

| SABA + IPRA + LABA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SABA + IPRA + LABA + ICS | 0.88 (0.56–1.38) | 0.99 (0.67–1.46) | 1.08 (0.60–1.9) | 1.42 (0.61–3.3) |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; IPRA = ipratropium bromide; LABA = long-acting β-agonist; MV = mechanical ventilation; SABA = short-acting β-agonist.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, classes of medications, nursing home status, current tobacco use, Charlson composite score, ICU admission, and receipt of guideline-concordant antibiotics.

Discussion

In this study, we found that among patients hospitalized for pneumonia, those with a preexisting diagnosis of COPD and prior use of ICS had significantly lower rates of 30- and 90-day mortality and use of mechanical ventilation. In addition, when we compared those who received a given regime of pulmonary medications ± ICS we found no association with worse outcomes. Several studies have demonstrated that use of ICS is associated with an increased incidence of pneumonia (4–8); however, our research did not demonstrate a significant association between use of ICS and increased mortality after pneumonia.

Although use of ICS has been shown to reduce the frequency of exacerbations and improve quality of life in patients with COPD (24), studies have consistently shown an increased risk of pneumonia for those receiving ICS as part of therapy for COPD (4–8, 25, 26). Unfortunately, the randomized control studies of use of ICS in COPD were limited by no formal definition of pneumonia, and by the small number of patients who developed pneumonia, so they were unable to address whether mortality is increased for those patients on ICS who do develop pneumonia. To date, only Ernst and colleagues (6) has shown an association between increased pneumonia-related mortality and receipt of ICS. Malo de Molina and coworkers (12), using a similar but less extensive and detailed database, demonstrated that receipt of ICS was associated with decreased 30- and 90-day mortality for those patients with COPD hospitalized with pneumonia.

Our study found that use of ICS in patients with COPD hospitalized with pneumonia was associated with decreased mortality. One potential explanation for these findings is the effect of corticosteroids on the inflammatory response. ICS have been shown to reduce both nonspecific inflammation and neutrophil influx into the lungs (27–30). It might be expected that reducing the inflammatory response would negatively impact clinical outcomes, but evidence suggests that an excessive inflammatory response may have harmful effects during an infection (31). ICS treatment may suppress the inflammatory response during the acute infection, blocking an excessive inflammatory response and the related harmful effects. Similarly, excessive neutrophil sequestration in the lungs may cause a variety of lung diseases and injuries (32, 33). The presence of microorganisms during pneumonia leads to increased leukocyte migration. This effect may be counterbalanced by ICS treatment, preventing excess sequestration and subsequent lung injury. Another possible explanation for our findings is that ICS treatment may reduce bacterial load. Reduction of bacterial load by ICS has been demonstrated in a mouse model of lung infection where inhaled fluticasone proprionate reduced the invasion of airway epithelial cells by Streptococcus pneumonia and Haemophilus influenza (34).

Although our study was a large database analysis and subject to the recognized limitations of such studies, we carefully assembled our cohort from complete patient discharge data to avoid ascertainment bias. Our sample was predominantly men because of our use of VA administrative data, and it is possible that women may have differential responsiveness to ICS compared with men. Because of the lack of pulmonary function data in these databases, we had to rely on ICD-9 codes and medication use to define COPD. However, a recent paper demonstrated that 80% of VA patients with an ICD-9 code of COPD had pulmonary function tests consistent with COPD (35). In addition, the proportion of patients with COPD in each GOLD class group using COPD medications increases by class, with 59% of GOLD class 1–2 and 91% of class 3–4 using these medications (35). Prior studies have also demonstrated that clinicians frequently treat patients without these data (36). We believe that those with exposure to ICS would be much more likely to have pulmonary function tests confirming COPD diagnosis, be more likely to have severe COPD, and therefore be at high risk of death compared with those who do not meet spirometry criteria for COPD. In addition, we are unable to examine the impact of use of ICS on the incidence of hospitalization for pneumonia, and therefore are unable to determine if this might impact our results. We are also unable explicitly to examine issues regarding adherence and quality of care because of the data sources. Finally, as in any nonexperimental study, we are unable to state that the use of ICS in patients with COPD reduces mortality.

In conclusion, we show that prior outpatient therapy with ICS was associated with significantly lower 30- and 90-day mortality in patients with COPD who were hospitalized with pneumonia, after adjusting for potential confounders. Additional studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of these medications in patients with COPD and for those who develop pneumonia while using them.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant Number R01NR010828 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System. Dr. Restrepo is supported by a Department of Veteran Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 17 new faculty grant and National Health Institute Grant KL2 RR025766. Dr. Copeland is supported by Veterans Health Administration Grant MRP-05–145. The funding agencies had no role in conducting the study, or role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Contributions: Funding: E.M.M.; conception and design: E.M.M., M.I.R., A.A.; analysis and interpretation: E.M.M., M.I.R., A.A., D.C., M.J.V.P., M.L.M.; drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: D.C., M.J.F., A.A., M.I.R., M.J.P., M.L.M., B.N., C.G.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2070OC on April 21, 2011

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1436–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Ma P, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care 2001;46:798–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, Jones P, Pride N, Gulsvik A, Anderson J, Maden C. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:449–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, Murphy DJ, Fan E. Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:2407–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Amin AV, Loke YK. Long-term use of inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst P, Gonzalez AV, Brassard P, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroid use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Balanzo X, Gonzalez CA. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study. Eur Respir J 1999;13:349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farr BM, Bartlett CL, Wadsworth J, Miller DL. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia diagnosed upon hospital admission. British Thoracic Society Pneumonia Study Group. Respir Med 2000;94:954–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rello J, Rodriguez A, Torres A, Roig J, Sole-Violan J, Garnacho-Montero J, de la Torre MV, Sirvent JM, Brodi M. Implications of COPD in patients admitted to the intensive care unit by community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1210–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Restrepo MI, Mortensen EM, Pugh JA, Anzueto A. COPD is associated with increased mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;28:346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tejerina E, Frutos-Vivar F, Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Palizas F, Gonzalez M, Apezteguia C, Abroug F, Matamis D, Bugedo G, et al. Prognosis factors and outcome of community-acquired pneumonia needing mechanical ventilation. J Crit Care 2005;20:230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malo de Molina R, Mortensen EM, Restrepo MI, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ, Anzueto A. Inhaled corticosteroid use is associated with lower mortality for subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hospitalized with pneumonia. Eur Respir J, 2010;36:751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown SH, Lincoln MJ, Groen PJ, Kolodner RM. VistA–US Department of Veterans Affairs national-scale HIS. Int J Med Inform 2003;69:135–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marrie TJ, Durant H, Sealy E. Pneumonia–the quality of medical records data. Med Care 1987;25:20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittle J, Fine MJ, Joyce DZ, Lave JR, Young WW, Hough LJ, Kapoor WN. Community-acquired pneumonia: can it be defined with claims data? Am J Med Qual 1997;12:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronsky D, Haug PJ, Lagor C, Dean NC. Accuracy of administrative data for identifying patients with pneumonia. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care 2004;42:355–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:854–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortensen EM, Coley CM, Singer DE, Marrie TJ, Obrosky DS, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ. Causes of death for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr 2006;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:S27–S72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, Yates JC, Vestbo J. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kardos P, Wencker M, Glaab T, Vogelmeier C. Impact of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate versus salmeterol on exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:144–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes NC, Qiu YS, Pavord ID, Parker D, Davis PA, Zhu J, Johnson M, Thomson NC, Jeffery PK. Antiinflammatory effects of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate in chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:736–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llewellyn-Jones CG, Harris TA, Stockley RA. Effect of fluticasone propionate on sputum of patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:616–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sin DD, Lacy P, York E, Man SF. Effects of fluticasone on systemic markers of inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:760–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Overveld FJ, Demkow UA, Gorecka D, Zielinski J, De Backer WA. Inhibitory capacity of different steroids on neutrophil migration across a bilayer of endothelial and bronchial epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2003;477:261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lekkou A, Karakantza M, Mouzaki A, Kalfarentzos F, Gogos CA. Cytokine production and monocyte HLA-DR expression as predictors of outcome for patients with community-acquired severe infections. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004;11:161–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kambas K, Markiewski MM, Pneumatikos IA, Rafail SS, Theodorou V, Konstantonis D, Kourtzelis I, Doumas MN, Magotti P, Deangelis RA, et al. C5a and TNF-alpha up-regulate the expression of tissue factor in intra-alveolar neutrophils of patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Immunol 2008;180:7368–7375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zemans RL, Colgan SP, Downey GP. Transepithelial migration of neutrophils: mechanisms and implications for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:519–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbier M, Agusti A, Alberti S. Fluticasone propionate reduces bacterial airway epithelial invasion. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1283–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joo MJ, Lee TA, Bartle B, van de Graaff WB, Weiss KB. Patterns of Healthcare Utilization by COPD Severity: a pilot study. Lung 2008;186:307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee TA, Bartle B, Weiss KB. Spirometry use in clinical practice following diagnosis of COPD. Chest 2006;129:1509–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]