CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

This review highlights the lack of an obvious airway phenotype when cell junction and adhesion genes are mutated in humans or deleted in murine models. This data will assist researchers in understanding the roles of compensatory cell junction proteins in the airway and help clinicians to search for a subtle airway phenotype.

The conducting airway of the lung is lined with respiratory epithelia. These epithelial cells are connected to each other and to the extracellular matrix by cell junction proteins. Not only do cell junction proteins provide a physical connection between cells, but they also mediate transport between cells, segregate apical from basolateral membrane proteins, and assist in cell signaling. One way to investigate the contribution of a pathway for epithelial function is to examine how disrupting a gene functionally affects the phenotype. Classical examples in the lung include the study of mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene (1), aquaporins (2), epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) (3), and their effect on pulmonary function. This raises the question of how mutations in cell junction genes expressed in airway epithelia might affect the lung.

REVIEW OF CELL JUNCTION MOLECULES

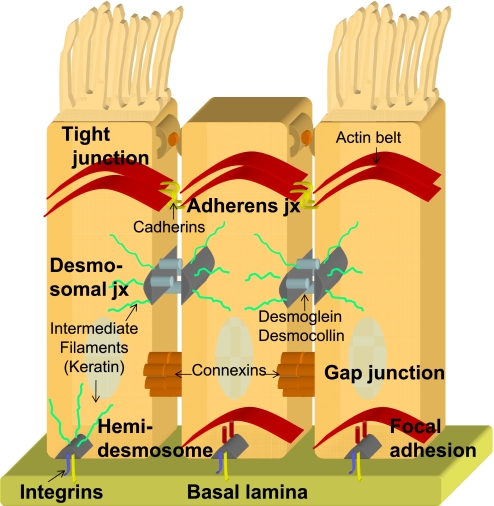

Epithelia line all cavities and surfaces of the body and are composed of cells tightly bound to each other (cell–cell junction) and to the basement membrane (cell–matrix junction). The tight junction is the most apical protein complex of the cell junction proteins, thus the cell membrane above the tight junction is called the “apical membrane.” In the lung, the apical surface is exposed to an air–liquid interface. Several ion channels, water channels, receptors, and mucins are expressed specifically on the apical surface. Moreover, this apical surface varies between ciliated, goblet, and nonciliated cells. The remainder of the cell membrane below the tight junctions is the basolateral membrane. The lateral membrane connects neighboring cells via cell–cell junction molecules, such as tight junctions, adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes. The basal membrane attaches to the basement membrane of the extracellular matrix (basal lamina) via cell–matrix junction molecules, such as integrins, focal adhesions, and hemi-desmosomes (Figure 1). Several ion channels, water channels, pumps, and receptors are localized specifically to the basolateral membrane. We will briefly review the cell junction molecules and highlight human phenotypes associated with cell junction gene mutations.

Figure 1.

Diagram of cell junction proteins and their location. Representation of cell–cell junction (abbreviated as jx) proteins (tight junctions, adherens junctions, desmomsomal junctions, and gap junctions) and cell–matrix junction proteins (hemi-desmosomal junctions, focal adhesions, and integrins) between epithelia (ciliated and nonciliated).

TIGHT JUNCTIONS

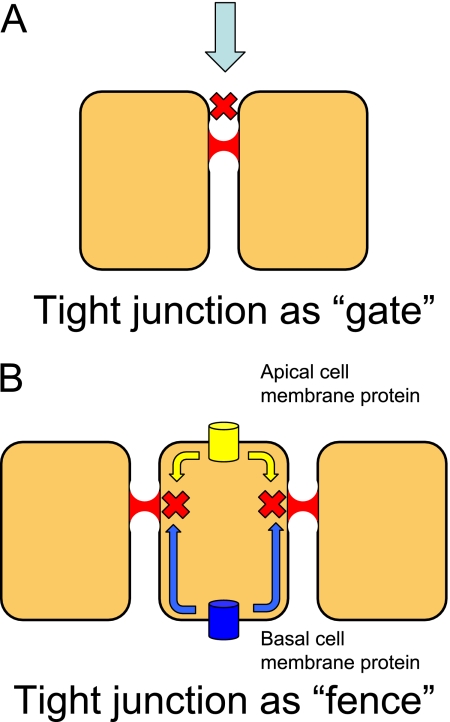

Tight junctions are the most apical cell junction proteins and because of their location divide the cellular membrane into the apical membrane above the junction and the basolateral membrane below the tight junction. Tight junctions regulate both the “gate” and “fence” functions of the epithelial membrane. The gate function seals off the paracellular compartment from particles, cells, ions, and solutes (Figure 2A). Tight junctions can regulate the paracellular permeability of a membrane by allowing selective diffusion between the apical and basolateral compartments (4). Epithelia with tight junctions that are highly impermeable to ions are called “tight epithelia” such as in the cochlea; whereas epithelia with high permeability to ions are called “leaky epithelia” such as in the ascending part of Henle's loop in the kidney (5). The fence function of the tight junction restricts diffusion of membrane proteins and lipids between the apical and basolateral surface, thus playing a role in maintaining polarity (Figure 2B). This fence prevents apical membrane proteins from traveling to the basolateral membrane and vice-versa.

Figure 2.

Representation of the two functions of the tight junction protein. (A) The tight junction can function as a gate by regulating paracellular transport between cells (demonstrated by red X). (B) The tight junction can also act as a fence, preventing apical cell membrane proteins from transporting to the basolateral surface and vice versa (demonstrated by red X).

The transmembrane tight junction proteins include claudins, occludins, and tricellulin. The cytoplasmic tight junction proteins include the zona-occludens, cingulin, and MAGI proteins that anchor the tight junction to the cellular actin cytoskeleton. The extended superfamily of claudins includes 24 different isoforms that are differentially expressed in specific tissues. Occludin and tricellulin are also transmembrane tight junction proteins that span the membrane four times with two extracellular loops. The occludin protein was the first tight junction protein to be identified and is found in nearly all tight junctions except for endothelial cells of nonneuronal tissue and the Sertoli cells of the testes (6, 7). Tricellulin has a similar structure as occludin but is found at cellular junctions where three epithelial cells are in contact with each other (8).

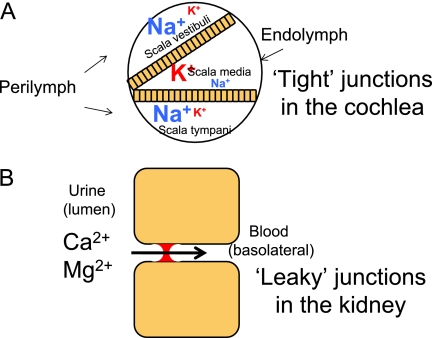

Tight junctions can act as a gate to maintain ionic gradients between fluid compartments. For example, the inner ear is separated into three different fluid compartments (scala vestibuli, scala media, and scala tympani) by the cochlear epithelia of Reissner's membrane and the basilar membrane. The scala vestibuli and scala tympani are filled with perilymph, with a high sodium and low potassium concentration. The scala media is filled with endolymph, with a high potassium and low sodium concentration (Figure 3). Tight junctions prevent sodium and potassium transport between the perilymph and endolymph, allowing the scala media to maintain a high positive resting potential. If this epithelia is not “tight,” and the endolymph potential falls to zero, then this leads to hair cell death and subsequently deafness. Mutations in claudin 14 have been found to cause human autosomal recessive deafness (9). A mouse knockout model of claudin 14 found that deafness was secondary to the loss of the endocochlear potential and death of sensory hair cells (10).

Figure 3.

The tight junction regulating paracellular transport in health and disease. (A) In the cochlea, tight junctions of the cochlear membrane separate perilymph and endolymph, maintaining an endocochlear gradient necessary for hearing. The large font represents the ion in higher concentration, and the smaller font the ion in a smaller concentration. This is an example of a “tight” seal. (B) In the ascending loop of Henle in the kidney, the tight junction regulates the absorption of calcium and magnesium from the urine into the bloodstream. This is an example of a “leaky” seal. Mutations in claudin 16 prevent renal absorption of these ions, causing a buildup of calcium and magnesium in the urine that can lead to renal disease.

Tight junctions can also be “leaky,” allowing the selective absorption and secretion of ions between the apical and basolateral compartments. Claudin 16 is a tight junction protein expressed in the ascending part of Henle's loop in the kidney and regulates paracellular absorption of magnesium and calcium from the urine into the bloodstream (Figure 4). Mutations in claudin 16 can cause autosomal recessive familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis, which is characterized by a failure to absorb magnesium and calcium in the urine, which can lead to progressive renal disease (11).

Figure 4.

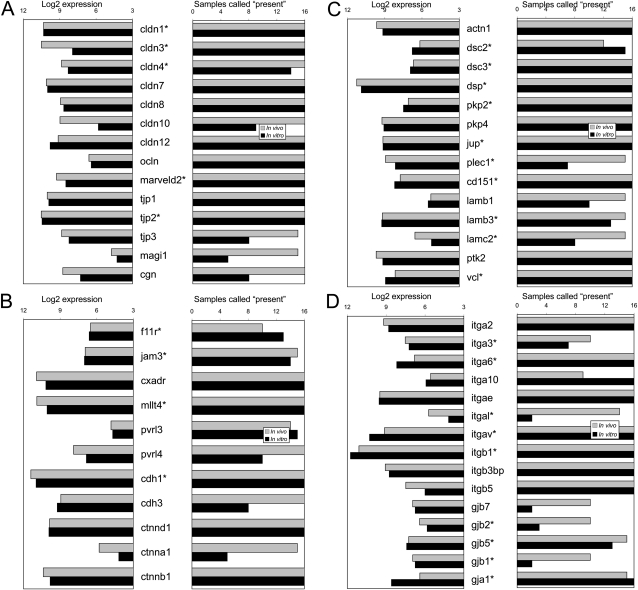

Cell junction gene microarray analysis of in vivo and in vitro airway epithelia. (A) Tight junction proteins; (B) Adherens proteins; (C) Desmosomal, hemi-desmosomal, and focal adhesion proteins; (D) Integrin and gap junction proteins; *cell junction genes that exhibit a human phenotype when mutated

ADHERENS JUNCTIONS

Adherens junctions provide cell–cell adhesion through the interaction of transmembrane proteins that attach to the intracellular actin skeleton. The adherens junctions are composed of three different complexes: the cadherin-catenin, the nectin-afadin, and the junctional adhesion molecule complexes (JAM). The cadherins are homophilic Ca2+-dependent adhesion transmembrane proteins that share a highly conserved intracellular armadillo-repeat family component. Although there are many cadherins, epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) is most commonly expressed in epithelia. The associated intracellular catenin molecules include α-catenin, β-catenin, plakoglobin (γ-catenin) and p120 catenin that bind cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton. Similar to cadherins, nectins are Ig-like adhesion transmembrane receptors that bind to other homophilic or heterophilic nectins. The intracellular nectin component has a highly conserved (PDZ)-binding domain. Afadin is an intracellular protein that binds to this PDZ domain and links nectin to the actin cytoskeleton (12).

Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) are cell junction proteins related to the Ig-like superfamily. This family also includes the coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CAR), named for the virus receptor that allows entry and infection into the cell. The JAM family of proteins has been categorized as belonging to the tight junction, but we classify these proteins as part of the adherens proteins because they are located inferior to the tight junctions (4). We have found that opening the tight junctions with EDTA greatly enhances adenovirus and reovirus interactions with CAR (13). Anchoring proteins, such as cingulin, link JAM proteins to the actin cytoskeleton via their PDZ-binding domain. JAM and CAR cell-junction proteins play key roles in cell signaling of airway epithelia in inflammation and disease (14).

Familial mutations of epithelial cadherin, or E-cadherin, have been linked to diffuse gastric cancer (15). The loss of the adherens junction in these tumor cells frees the confining restraints of contact inhibition that can lead to metastasis of the tumor cell. In the lung, in vitro and in vivo animal studies have shown changes in adherens junction protein expression levels in response to inflammation (16) and lung injury (17). There is extensive literature that investigates changes in cell adhesion molecules and lung metastasis (18). Although important, these specific changes in gene expression of cell adhesion molecules in inflammation, injury, and tumorigenesis are beyond the scope of this review article.

DESMOSOMAL JUNCTIONS

Desmosomal junctions are similar to adherens junctions, in that they are cell–cell adhesion molecules. They differ in that desmosomal junctions link the extracellular component of cell junctions to the intracellular intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Desmosomal junctions are composed of the extracellular component of desmogleins and desmocollins that belong to the cadherin family. Within the cell, these cadherins are linked to the intermediate filament cytoskeleton by the desmosomal plaque proteins desmoplakin, desmoglein, and plakoglobin (19).

Mutations in desmosomal junction proteins can lead to skin fragility and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. Mutations in desmoglein 1 are responsible for autosomal dominant striate palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and mutations in plakophilin 1 are responsible for autosomal recessive ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome. Electron microscopy of the skin in these diseases shows widening of the intercellular spaces between the keratinocytes and loss of epithelial integrity (20, 21).

HEMIDESMOSOMAL JUNCTIONS AND FOCAL ADHESIONS

Hemidesmosomal junctions and focal adhesions anchor basal epithelial cells to the extracellular matrix of the basement membrane. Hemidesmosomal junctions, focal adhesions, and integrins belong to the family of cell-matrix adhesion molecules. The hemidesmosomal proteins BP230 and plectin bind to cytosolic keratin of the epithelial cell (22). The focal adhesion proteins talin, α-actinin, filamin, vinculin, and focal adhesion kinase bind to the actin cytoskeleton of the epithelial cell (23). Both hemidemosomes and focal adhesions use cell adhesion integrins to span the transcellular space and bind with laminin in the extracellular matrix.

Mutations in hemidesmosomal junctions and focal adhesions can cause shearing and separation of epithelial cells to the basement membrane, particularly in organs with high mechanical stress or friction. The skin is constantly exposed to friction, and in junctional epidermolysis bullosa, the epidermis separates from the basement membrane causing an inherited blistering disease of the skin. Mutations in BP180, plectin, and laminin can cause junctional epidermolysis bullosa in both Herlitz (severe) and non-Herlitz (moderate) forms of epithelial separation (24).

INTEGRINS

Integrins are cell adhesion glycosylated heterodimer receptors composed of a pair of one α and one β subunit. There are 18 α and 8 β subunits, forming at least 24 different integrin combinations. Integrins are the principal adhesion molecules that anchor epithelial cells to the basement membrane in focal adhesions and hemidesmosomal junctions. Integrin expression is not limited to epithelial cells but is also expressed on leukocyte cells, which are critical for the cellular response in inflammation and injury.

Although integrins comprise the physical unit that joins epithelial cells to the basement membrane, they also interact with the extracellular matrix and are critical in cell signaling. Integrins in epithelial cells and leukocytes can mediate and influence cell shape, motility, growth, and progression through the cell cycle. Integrins can participate in “outside-in” signaling in that they can recruit cytoskeletal proteins and intracellular signaling cascades. Integrins can also participate in “inside-out” signaling, where the cell can modify the adhesive property of the extracellular integrin.

Genetic mutations in integrins can lead to immune deficiencies, bleeding disorders, skin disorders, and congenital muscular dystrophy. Integrin β2 mutations, also known as CD18 mutations, can cause leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD) type 1 (25, 26). LAD is secondary to impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion leading to impaired immune deficiency and recurrent bacterial infections. Mutations in either the α2b or the β3 subunit can cause Glanzmann thrombasthenia, a bleeding disorder secondary to impaired platelet adhesion. Although there have been a few mouse lung phenotypes described in integrin knockout models related to neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion (27, 28), there are no human lung diseases associated with integrin mutations.

GAP JUNCTIONS

Gap junctions are direct connections between cells that allow transport of ions and solutes from one cell to another. They are composed of connexin proteins that are ubiquitously expressed in the human body. There are 20 different connexins, which are labeled by their molecular mass and subgroup (α, β, or γ). Six connexins form one connexon, which is half of a gap junction. Gap junctions are important in cell–cell signaling, morphogenesis, and regulation of growth signals. Mutations in the human connexin family have been implicated in epithelial diseases of the eye, ear, skin, and the nervous system, highlighting their importance in a variety of different tissues and functions (29).

For example, gap junctions in neuron cells facilitate communication between the Schwann cell and axon. In X-linked Charcot Marie tooth disease, connexin mutations can block this communication and lead to progressive degeneration of peripheral nerves. Gap junctions in the lens of the eye regulate oxygenation and hydration. Connexin mutations can lead to cataract formation from cell death and subsequent lens opacification. Last, connexins are critical in maintaining the potassium/sodium balance of the endolymph of the inner ear. Mutations in the gap junction connexin 26 lead to the most common inherited form of deafness (30).

CELL JUNCTION MOLECULES EXPRESSED IN AIRWAY EPITHELIA

Review Methodology

A comprehensive list of cell junction genes in human epithelia was compiled by reviewing the literature. Global expression of the cell junction protein was verified in normal tissue by utilizing the protein immunochemistry information provided by the Human Protein Atlas website (31). The Human Protein Atlas is a publicly available database containing immunohistochemistry staining of 48 different normal human tissues to many different antibodies. These antibodies have been validated through immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis. Although there are limitations in the use of the Human Protein Atlas, it is an excellent resource for the purpose of this review and one method to support the presence of cell adhesion molecules in multiple organ systems. We investigated individual cell adhesion molecule staining in multiple organ systems including the gut, lung, kidney, hepatobiliary system, and the skin. In the lung, we focused on airway epithelia including tracheal and bronchial tissue. However, clinical phenotypes resulting from altered function in lung interstitium or the alveolar capillary bed would have been identified in either mice or humans. Tissues classified as staining strong or moderate were confirmed by reviewing the histology staining pattern on the slide. Genotype-phenotype correlations were recorded by reviewing original publications via the PubMed database for germline mutations in cell junction genes and their phenotypes in both human and animal models.

Pulmonary expression of cell adhesion proteins was quantified using microarray analysis of in vivo and in vitro lung tissue. Our group recently performed microarray analysis of in vivo lung tissue from the trachea and bronchus obtained from eight healthy subjects without lung disease (32). Airway epithelia gene expression in vivo can be confounded by non-epithelial cells so we also used an in vitro model free of inflammatory of fibroblast cells. Moreover, this model will allow for the investigation of subtle phenotypes. In vitro tracheal and bronchial epithelial tissue was cultured and grown from eight individual human donor lungs without primary lung disease, whose lungs were determined to be unsuitable for lung transplantation, in an air–liquid interface on millicells, as previously described (33). Cells were used after 2 weeks in culture, when cellular differentiation is reached and transepithelial resistance is 700–1,200 Ωcm2. Microarray expression was quantified on a logarithmic scale and via the Affymetrix algorithm to determine “present” and “absent” calls on the samples. To increase the specificity of the microarray, probes with present calls in less than 10 out of 16 samples in each group were excluded from the analysis.

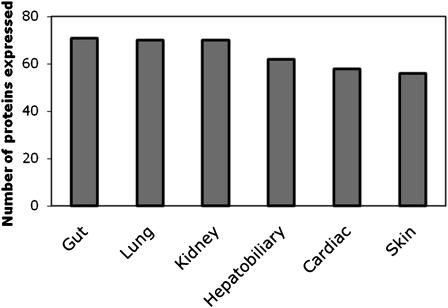

Cell Junction and Adhesion Proteins Are Expressed in Multiple Organs, Including the Lungs

We reviewed a total of 122 cell junction and adhesion genes (Table 1). Although this list is not exhaustive, we believe it is a comprehensive effort to characterize many genes from different cell junction and adhesion classes. We investigated specific pulmonary expressions of cell junction proteins by microarray analysis of in vivo and in vitro lung tissue. Fifty-four cell junction and adhesion genes were present using our microarray algorithm in either in vivo or in vitro lung tissue (Figure 4). Because microarray analysis examines mRNA expression, we also looked at immunochemistry staining in the lungs. We were able to obtain protein expression profiles for 71 of the cell junction and adhesion genes from the Human Protein Atlas website. Nearly all of these adhesion proteins (70/71) stained positive in the lungs. Cell junction and adhesion proteins were ubiquitously present in the gut, kidney, and lungs with a majority also present in the hepatobiliary system, heart, and skin (Figure 5). Based on these data we would expect that mutations in some of these proteins would result in alterations of the epithelia that may predispose, cause, or modify the course of lung diseases.

TABLE 1.

GENOTYPE-PHENOTYPE OF CELL JUNCTION GENE MUTATIONS

| Cell junction Protein | Gene Symbol | Human Mutation | Micro-Array Present in Lung | Human Protein Atlas Staining in Lung | Human Phenotype | Mouse Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tight junction proteins | ||||||

| Claudin-1 | CLDN1 | 200-201TT (44), 358delG (45) | Y | Y | Neonatal icthyosis-sclerosing cholangitis syndrome. Inflammation and obliterative fibrosis of the intra and extrahepatic bile ducts; ichthyosis and sclerosing cholangitis affecting skin and bile ducts | Perinatal lethality:epidermal barrier affected; animals die within 1 d of birth; severe dehydration due to excessive water losses (46) |

| Claudin-2 | CLDN2 | N | Y | Up-regulated in Crohn's disease | ||

| Claudin-3 | CLDN3 | Large single allele deletion | Y | Y | Williams-Beuren syndrome: developmental defects, hypercalcemia, constipation | |

| Claudin-4 | CLDN4 | Large single allele deletion | N | Y | Williams-Beuren syndrome | |

| Claudin-5 | CLDN5 | Large single allele deletion | N | Y | VCFS, 22q11 | Perinatal lethality: increased permeability of blood brain barrier (47) |

| Claudin-9 | CLDN9 | N/A | Y | Deafness in mice (48) | ||

| Claudin-11 | CLDN11 | N | Y | Associated with autoimmunity of MS | Loss of endocochlear potential, CNS myelin defect, male sterility, hind limb weakness, deafness (49) | |

| Claudin-14 | CLDN14 | 398delT, VAL85ASP (9), GLY101ARG (50) | N | N/A | Autosomal recessive deafness | Phenocopy of human deafness; normal endocohlear potential but progressive degeneration of hair cells (10) |

| Claudin-16 | CLDN16 | Multiple (11), (51), (52) | N | Y | Familial hypomagnesemia w/hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis: patients present with UTI, polyuria, hematuria, hypomagnesemia then ESRD | Claudin 16 knockdown (53): stunted growth, altered electrolytes |

| Claudin-19 | CLDN19 | G20D, Q57E, L90P (54) | N | N/A | HOMGO, renal hypomagnesemia renal with ocular abnormalities | Schwann cell barrier defect; behavior defect (55) |

| Occludins | OCLN | Y | Y | Viable with complex phenotype; no paracellular defects, no gastric parietal cells; postnatal growth retardation, abnormalities in testis leading to male infertility, inability of females to suckle young, salivary gland abnormalities, thinning of compact bone, brain calcium deposits, chronic gastritis, hyperplasia of gastric epithelium (7) | ||

| Tricellulin | MARVELD2 | IVS3-1G > A; IVS4+2delTGAG; IVS4+2T > C; 1498C > T (56); IVS4DS(57) | Y | N/A | Autosomal recessive deafness | |

| zo-2 (TJP2) | TJP2 | VAL48ALA(58) | Y | Y | Familial hypercholanemia: elevated serum bile acid concentrations, itching, and fat malabsorption; misssense mutation associated with defective bile secretion | Neonatal lethal: arrest in early gastrulation (59) |

| Adherens junctions | ||||||

| Junctional adhesion molecule-1 | F11R | Y | Y | Increased trafficking of dendritic cells to lymph nodes, activation of specific immunity (60) | ||

| Junctional adhesion molecule-3 | JAM3 | Y | Y | Growth retardation, pneumonia, poor survival, mega-esophagus, altered airway responsiveness, increasing granulocytes (38) | ||

| CAR: Coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor | CXADR | Y | Y | Embryonic lethality with focal cardiomyocyte apoptosis and extensive thoracic hemorrhaging (61) | ||

| Afadin | MLLT4 | Y | N | Homozygous mice display embryonic lethality, abnormal ectoderm including disrupted cell jx, absence of somites, notochord, allantois, and neural folds (62) | ||

| Nectin-1 | PVRL1 | W185X, 1-BPDEL, 1-BP DUP (63) | N/A | Y | Cleft-lip palate, ectodermal dysplasia | |

| E-cadherin | CDH1 | Multiple (15), (64), (65), (18), (66), (67), (68) | Y | Y | Familial gastric CA with or without CL/P; somatic mutations associated with many CA | Neonatal lethal (69) |

| N-cadherin | CDH2 | N/A | Y | Perinatal lethality: myocardium dissociates, somites and neural tube poorly organized (70) | ||

| P-cadherin | CDH3 | 1-BP DEL 981G (71), ARG503HIS (72), ASN322ILE, 1-BP DEL 829G (73) | Y | Y | Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy: early hair loss followed by progressive degeneration of the central retina leading to blindness | Normal, fertile, except for precocious mammary gland development (74) |

| P120-catenin | CTNND1 | Y | Y | Develop inflammatory skin lesions with age (75) | ||

| Alpha-catenin | CTNNA1 | Y | Y | Embryonic lethal; conditional knockout: blockage of hair follicle development, defects in adherens junction formation, intercellular adhesion, and epithelial polarity(76) | ||

| Beta-catenin | CTNNB1 | Somatic mutations in tissues | Y | Y | Mutations cause (via activation Wnt pathway): endometrial, hepatocellular, endometrioid type ovarian, anaplastic thyroid, colorectal, squamous cell, prostate, pancreatic, melanoma, hepatoblastoma, desmoid tumor, pilomatricoma, medulloblastoma (77) | Unable to form dorsal structures and die before gastrulation due to impaired Wnt pathway signaling(78) |

| Desmosomal junctions | ||||||

| Desmocollin 1 | DSC1 | N/A | Y | Flaky skin, punctate epidermal barrier defect (79) | ||

| Desmocollin 2 | DSC2 | 1-bp DEL, 1430C, 2-BP INS, 2687GA (80); IVS5AS, A-G,-2 (81) | Y | Y | Can cause (arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia) | |

| Desmocollin 3 | DSC3 | Y | N/A | Embryonic lethal (82) | ||

| Desmoglein 1 | DSG1 | IVS2AS (21)(Rickman) | N/A | Y | Striate palmoplantar keratoderma; pemphigus foliaceous; bullous Impetigo; staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | |

| Desmoglein 2 | DSG2 | Multiple (83), (84); (85) | N | Y | Arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with one case of skin ulcerations | Embryonic lethal (86) |

| Desmoglein 3 | DSG3 | N | N | Pemphigus vulgaris antigen | Oral lesions, low weight, crusting of skin and suprabasilar acantholysis, hair loss (87) | |

| Desmoglein 4 | DSG4 | EX5-8DEL (88) | N/A | N/A | Localized recessive hypotrichosis and recessive monilethrix | Abnormal short hair and thickened skin (88) |

| Desmoplakin | DSP | Multiple (89), (90); (91); (92); (93); (94) (95) | Y | N/A | AD: Striate palmoplantar keratoderma AR:(1) wooly hair, keratoderma, cardiomyopathy; (2) RV cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia; (3) striate palmoplantar keratoderma; (4) lethal acantholytic epidermolysis bullosa: fatal skin fragility, alopecia, nail loss, neonatal teeth | Knockout mice die E6.5 from extra-embryonic tissue defects. Rescued embryos die E9.5 of heart, epidermal, vascular and neuroepithelial defects (96, 97) |

| Plakophilin 1 | PKP1 | GLN304TER, 28-BP DUP, NT1132 (20), IVS6,A-T,-2 (98) | N | N/A | Ectodermal dysplasia: skin fragility, ectodermal dysplasia syndrome | |

| Plakophilin 2 | PKP2 | ARG79TER, ARG735TER, IVS10,G-C,-1, IVS12,G-A,+1 (99) | Y | Y | RV cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia | Embryonic lethal: lethal alterations in heart morphogenesis and stability at midgestation (100) |

| Plakoglobin (gamma-catenin) | JUP | 2-BP Del, 2157TG Deletion (102); 3-BP INS, 117 GCA(102) | Y | Y | Naxos disease:heart, skin, and hair abnormalities | Lethal and die at E10.5-12.5 due to severe heart defects from impaired desmosome formation(78) |

| Hemi-desmosomal junctions | ||||||

| BP180 | COL17A1 | Multiple (103), (104), (105), (106), (107), (108), (109), (110) | N | N/A | Autoimmune target for bullous pemphigoid, cicatrial pemphigoid, linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis, pemphigoid gestationis; genetic target of junctional EBnon-Herlitz; generalized atrophic epidermolysis bullosa. | |

| Plectin | PLEC1 | Multiple (111), (112), (113), (114), (115), (116), (117) | Y | Y | Autoimmune target for bullous pemphigoid and cicatrial pemphigoid; genetic target of epidermolysis bullosa with muscular dystrophy | Die 2-3 d after birth. Phenotype of skin blistering, degeneration of keratinocytes. Abnormalities of myopathies in skeletal muscle and disintegration of intercalated discs in heart (118). |

| BP230 | BPAG1 | N | N/A | Autoimmune target for bullous pemphigoid | ||

| CD151 | CD151 | 1-BP INS, G383 (119) | Y | Y | Nephropathy with pretibial epidermolysis bullosa and deafness | Phenotypically normal, normal hemidesmosomes, but minor bleeding abnormalities (120) |

| Laminin alpha 3 | LAMA3 | 1-bp del, 300g (121), ARG650TER (122), GLN1368TER (24), 1-BP INS, 151G (123) | N | Y | Herlitz or non-Herlitz JEB, laryngoonychocutaneous syndrome | Neonatal lethality: junctional blisters in the skin w separation of dermal/epidermal jx (124) |

| Laminin beta 3 | LAMB3 | Multiple (125), (126), (127), (122), (128), (129), (130), (131) | Y | Y | Junctional epidermolysis bullosa (Herlitz and non-Herlitz) | |

| Laminin gamma-2 | LAMC2 | Multiple (132), (133), (134), (135), (24), (135) | Y | Y | JEB (Herlitz and non-Herlitz) | Skin blistering and neonatal death (137); widened tracheal hemidesmosomes but normal lung differentiation and morphology (43) |

| Focal adhesions | ||||||

| vinculin | VCL | 3-bp Del, 2862GTT, ARG975TRP (138) | Y | Y | Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

| Integrins | ||||||

| itga1 | ITGA1 | N/A | N/A | Increase in skin thickness, higher rate of collagen synthesis (139) | ||

| itga2 | ITGA2 | Y | Y | Polymorphisms: Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia | Morphologically normal, clinically without bleeding anomalies, but less adhesion to collagens in vitro(140) | |

| itga2b | ITGA2B | Multiple (141), (142), (143), (144), (145), (146), (147), (148), (149) | N | N | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | Mice with bleeding disorders similar to Glanzmann (150) |

| itga3 | ITGA3 | Y | N/A | Defects of kidney and SMG, decreased branching of lungs, skin blistering at dermal-epidermal jx, abnormal layering of cerebral cortex, perinatal lethality (37). Double knockout with ITGA6 can cause stunted lung development (35) | ||

| itga4 | ITGA4 | N | N/A | Embryonic lethality: cardiac abnormalities (151) | ||

| itga5 | ITGA5 | N | Y | Intracerebral hemorrhages at midgestation and death shortly after birth. Embryonic mesodermal defects (152). | ||

| itga6 | ITGA6 | 1-BP DEL 791C (153) | Y | Y | Epidermolysis bullosa with pyoric atresia | Normal development before birth. Phenotype reminiscent of human epidermolysis bullosa shortly after birth with death. Defects in cerebral cortex and retina (154) Double knockout with ITGA3 can cause stunted lung development (35) |

| itga7 | ITGA7 | 21-BP INS, 98-BP DEL, 1-BP DEL 1,204 (155) | N | Y | Congenital muscular dystrophy | Muscular dystrophy (155) |

| itga8 | ITGA8 | N | N | Majority die perinatal. Those that survive have defective kidney morphogenesis and ciliogenesis (156) | ||

| itga9 | ITGA9 | N | N/A | Born normally, but develop respiratory failure and die perinatally. Caused by accumulation of large volumes of pleural fluid; possible congenital chylothorax (42) | ||

| itga10 | ITGA10 | Y | N/A | Growth retardation of long bones (157) | ||

| itga11 | ITGA11 | N | N/A | Dwarfism, increased mortality with age, defective incisors (158) | ||

| itgad | ITGAD | N/A | N/A | Reduced staph enterotoxin-induced T cell response (159) | ||

| itgae | ITGAE | Y | N/A | Reduced numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes (160) | ||

| itgal | ITGAL | Mutations occur in itgb2 | Y | N | Binds to itgb2. Mutations in itgalb2 cause LFA1 immunodeficiency with defects in adhesion-dependent granulocyte, monocyte and B/T lymphocyte function. | Decreased leukocyte adhesion (40) |

| itgam | ITGAM | N/A | N | Reduced staph enterotoxin-induced T cell response (161) | ||

| itgav | ITGAV | Y | Y | 80% lethality. Intracerebral and intestinal hemorrhages and cleft palate. Exaggerated inflammation and protection from pulmonary fibrosis (161) | ||

| itgaw | ITGAW | N/A | N/A | |||

| itgax | ITGAX | N | N | Alterations in T cells and their response (40) | ||

| itgb1 | ITGB1 | Y | Y | Susceptibility to Hirschbrung disease | Homozygous null mutants are lethal (162) | |

| itgb2 | ITGB2 | ARG593CYS, LYS196THR (25), LEU149PRO, GLY169ARG (26), Initiation mutation (163) | N | Y | LAD1- Leukocyte adhesion deficiency with defects in adhesion-dependent granulocyte, monocyte and B/T lymphocyte function. | Homozygotes are subject to granulocytosis, impaired inflammatory and immune responses, chronic dermatitis. Increased circulating neutrophils, defective response to chemical peritonitis, delayed transplantation rejection (164). |

| itgb3 | ITGB3 | Multiple (165), (166), (167), (168), (169), (170), (171), (172), (141), (173); | N | N | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | Homozygotes exhibit platelet defects, extended bleeding, systemic bleeding (174) |

| itgb4 | ITGB4 | Multiple (175), (176), (177), (178), (179), (180), (181), (182) | N | Y | Epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. Epidermolysis bullosa, generalized atrophic benign. Epidermolysis bullosa of hands and feet | Perinatal lethality with extensive detachment of epidermis and other squamous epithelia. Stratified tissues lack hemidesmosomes and simple epithelia are defective in adherence (183) |

| itgb5 | ITGB5 | Y | Y | Phenotypically normal (184) | ||

| itgb6 | ITGB6 | N | N/A | Homozygotes exhibit baldness with macrophage infiltration of skin, exaggerated pulmonary inflammation, impaired mucosal mast cell response (39) | ||

| itgb7 | ITGB7 | N | N/A | Hypoplasia of gut-associated lymph tissue due to defects in lymphocyte migration | ||

| itgb8 | itgb8 | N | N/A | Embryonic or perinatal lethality with profound defects in vascular development (185) | ||

| Gap junctions | ||||||

| Cx26 | gjb2 | Multiple (186), (187), (188), (189), (190), (191), (192, ASP66HIS {Maestrini, 1,999 #52) (193), (194), (195), (196), (197), (198), (199), (200), (201), (202), (203), (204), (205), (206, 207), (208), | Y | Y | Deafness, skin disease | KO perinatal death with developmental retardation and impaired transplacental nutrient/glucose uptake. Conditional ear KO with deafness (209) |

| Cx30 | Gjb6 | THR5MET (210), GLY11ARG (211), VAL37GLU (212), 309-kb DEL, 232-kb DEL (213) | N/A | Y | Deafness, ectodermal dysplasia | Mutants display progressive HL (214) |

| Cx30.3 | Gjb4 | PHE137LEU (215), PHE137LEU, THR85PRO, GLY12ASP, ARG22HIS, PHE189TYR (216, 217) | N/A | N/A | Erythrokeratodermia variabilis | Mutants are normal, but altered sense of smell (218) |

| Cx31 | Gjb3 | Multiple (216, 217), (219), (220), (221), (222) | N | N/A | Deafness, EKV | Partial lethality and transient placental dysmorphogenesis but no impairment in hearing or skin differentiation (223) |

| Cx31.1 | Gjb5 | Y | N/A | KO with some embryonic lethality, reduced weight, reduced placental development (224) | ||

| Cx32 | Gjb1 | ARG142TRP, PRO172SER, VAL139MET (225), (226), (227), (228), (229), (230), (231), (232), (233), (234), (235), (236), (237) | Y | Y | X-linked CMTD | KO have decrease in body weight, enhanced neuronal sensitivity to ischemic insults, increased susceptibility to liver tumors (238) |

| Cx36 | Gjd2/gja9 | N/A | Y | KO mice have decreased electrical synapses in neocortex, decreased vision (239, 240) | ||

| Cx37 | Gja4 | N | N | Atherosclerosis, MI (Polymorphisms in gene associated with atherosclerosis and MI) | KO mice develop more atherosclerotic lesions (241) | |

| Cx40 | Gja5 | N | Y | Idiopathic A-fib (allelic variants) | KO mice have higher incidence of cardiac abnormalities and conduction deficiencies (242, 243) | |

| Cx43 | Gja1 | Multiple (245), (246), (247), (248), (249), a(250), (251) | Y | Y | Oculodentodigital dysplasia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, deafness | KO mice die postnatal due to failure of pulmonary gas exchange from blockage of RV outflow track of heart (251) |

| Cx46 | Gja3 | ASN63SER, 1137C INS (253), PRO187LEU (254), ARG76HIS (255) | N/A | N/A | Cataract, zonular pulverulent | Targeted disruption; homozygous mice developed nuclear cataracts (255) |

| Cx47 | Gjc2/gja12 | MET286THR, PRO90SER, 1-BP DEL, 989C, ARG240TER, TYR272ASP (256), 34-BP DEL, NT914 (257), 1-bp INS, 695G (258) | N/A | N/A | Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease; hypomyelinating leukodystrophy | KO mice w/o phenotype (259) |

| Cx50 | Gja8 | Multiple (260), (261), (262), (263), (264), (265) | N/A | N/A | Cataract, zonular pulverulent | Micropthalmia and nuclear cataracts (266) |

Definition of abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; Afib, Atrial fibrillation; AR, autosomal recessive; B/T, B-cell/T-cell; CA, cancer; CL/P, cleft lip/palate; CMTD, Charcot Marie Tooth Disease; CNS, Central Nervous System; E, Epithlial; EB, Epidermolysis Bullosa; ESRD, End Stage Renal Disease; EKV, erythrokeratodermia variabilis; FHHN, familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis; HL, Hearing loss; HOMGO, hypomagnesemia renal with ocular involvement; JEB, junctional epidermolysis bullosa; jx, cell–cell junction; KO, knockout; LAD1, Leukocyte Adhesion Disorder 1; LFA1, Lymphocyte Function-associated Antigen 1; MI, Myocardial infarction; MS, Multiple Sclerosis; RV, Right Ventricle; SMG, submucous gland; UTI, urinary tract infection; VCFS, Velo-Cardio Facial Syndrome; Wnt, catenation of Wg (wingless) and Int.

Analysis of cell junction gene mutations, protein expression via microarray and immunocytochemistry and the human and mouse phenotypes when mutated. A full table of all cell junction genes investigated, with additional information on expression is included as supplementary data.

Figure 5.

Cell junction protein expression by organ system. Number of proteins expressed by immunochemistry based on Human Protein Atlas data (31). Nearly all of the proteins were expressed ubiquitously throughout multiple organ systems.

Human and Mouse Mutations of Cell Junction and Adhesion Genes

One-third (44/122) of the cell junction and adhesion genes had human mutations as reported in the published literature. Table 1 presents a list of cell junction genes with a human mutation, a resulting human phenotype, and a knockout mouse phenotype. A complete list of cell junction genes with additional information on organ expression, microarray data, and inheritance pattern is available on the online supplement. Of those mutations that had an inheritance pattern, the majority (64%) were autosomal dominant (AD) versus 36% that were autosomal recessive (AR). Mutations were classified by type: missense (45%), nonsense (29%), splice (14%), and insertion/deletions (12%). The prevalence of autosomal dominant mutations is suggestive of gain of function mutations. These kinds of mutations could result in a phenotype, even if there are redundant proteins with similar function.

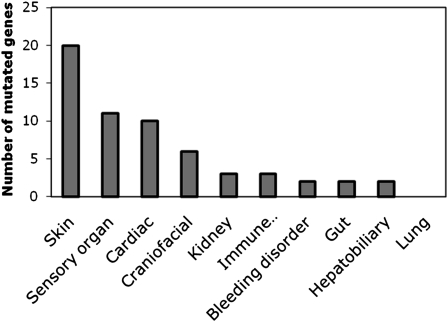

Cell Junction and Adhesion Gene Mutations are Reported to Have Phenotypes in Multiple Organ Systems, but None Are Reported to Involve the Lung in Humans

Human mutations in cell junction and adhesion genes expressed various phenotypes in multiple organ systems (Figure 6). Some mutations result in phenotypes that encompass multiple organ systems. For example, several genetic syndromes result in deafness and skin disorders. Surprisingly, none affect the lung. Those genes expressing phenotypes in the skin (20), sensory organs (11), and heart (10) predominated. These organs may be preferentially affected due to a high mitotic turnover rate, an obvious phenotype, or subject to repetitive stress. Surprisingly, even though many of the genes mutated were expressed in the lung, the review of the literature did not identify any lung phenotype. These results have several implications for airway epithelia cell biology, function, and disease in the lungs.

Figure 6.

Cell junction mutation phenotype in human organ systems. Cell junction mutations can exhibit a wide variety of phenotypes in multiple organ systems. Phenotypes in the skin, sensory organs, and cardiac system predominate. Surprisingly, there was no human lung phenotype found.

Targeted Deletions of Most Adhesion Molecules Do Not Result in a Lung Phenotype in Mice

Independently, both Hynes (34) and Sheppard (27) have reviewed the phenotype of cell junction and adhesion knockout models in mice. Interestingly, not all knockout mice had drastic phenotypes in the organs in which they were expressed. The phenotype in the lungs can present as defects in changes in development and morphogenesis, altered immune response to infectious challenges, and structural abnormalities.

Integrin α 3 (ITGA3) knockout mice, the integrin α 3 α 6 double knockout mice (ITGA3/ITGA6) (35), and the integrin 8 knockout mice (ITGA8) (36) have stunted lung development that can lead to decreased secondary branching of the lungs or the fusion of lung lobes (37). Integrins may be important in morphogenesis and development of the lung; however, there are no postdevelopmental lung consequences similar to the skin phenotype of epidermolysis bullosa in humans. Knockout models of junctional adhesion molecules and integrins can affect the immune response in mice, predisposing them to infection or protecting them from lung injury. Junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM3) knockout mice are predisposed to pneumonia secondary to an altered immune response in the airway (38). Interestingly, this enhanced inflammatory response in integrin α v (ITGAV) and integrin β 6 (ITGB6) knockout mice can lead to possible protection from pulmonary fibrosis (39–41). Both integrin and junctional adhesion molecules are important in cell signaling of epithelia in inflammation and disease. These molecules are also expressed on inflammatory cells, and the lung phenotype may actually be secondary to an impaired inflammatory response rather than an epithelial defect. Knockout models of integrins and laminins can also cause structural abnormalities leading to disease. Integrin α 9 (ITGA9) knockout mice have defective ciliogenesis and develop respiratory failure and accumulate large volumes of pleural fluid leading to perinatal death (42). Laminin C2 (LAMC2) knockout mice have altered tracheal hemidesmosomes but normal lung morphology and differentiation (43). Understanding the pathogenesis of how these knockout models produce a pulmonary phenotype in mice may translate to further testing and diagnosis in humans.

DISCUSSION

Whereas several phenotypes have been described in humans for genetic mutations of cell adhesion molecules, none appear to affect the lung. This is surprising and led us to explore three different explanations.

The Lung Phenotype Is Missed Because of Embryonic Lethality

Many cell junction and adhesion genes are critical for life and when mutated can cause embryonic or neonatal lethality. Mutations that affect the pulmonary system alone are unlikely to be missed, because lung viability is not necessary in utero and would be realized only when the first breath occurs. But mutations that affect multiple organ systems critical for intrauterine development such as the brain, skin, or heart may cause embryonic or neonatal lethality and therefore mask any pulmonary phenotype that could be present.

The Lung Phenotype Is Subtle and Therefore Missed

Many of the phenotypes affected by cell junction and adhesion gene mutations affect sensory organs or manifest as obvious physical findings. Even a casual observer can recognize mutations causing deafness, blindness, or skin blistering. But phenotypes involving the lung can be subtle and difficult to characterize. After reviewing the functions of cell junction proteins, we would expect a lung phenotype to present as changes in paracellular permeability, abnormal epithelial cell differentiation, impaired response to inflammation or injury, altered ion selectivity, and malignancy. Possible pulmonary phenotypes secondary to tight junction mutations could include changes in airway surface liquid composition from altered paracellular transport. Airway surface liquid is a thin layer of fluid bathing the apical surface of airway epithelia and its depth is measured in micrometers, making testing of the fluid very difficult. Adherens mutations could increase susceptibility to pulmonary neoplasms, as epithelia may metastasize and lose contact inhibition with neighboring cells. Desmosomal mutations could lead to damage and shearing of lung epithelia from the chronic stress of respiration or acute trauma that may be missed because the lungs are not visible. Integrin mutations could lead to increased pulmonary inflammation and infection that may not cause mortality, but may increase morbidity and go unrecognized. Finally, a pulmonary phenotype may not manifest unless the pulmonary system is challenged by infection or inflammation.

Compensatory Cell Junction and Adhesion Proteins in the Lungs

Because the lungs are critical for life, multiple cell junction genes with overlapping functions are likely expressed. Individual cell adhesion genes are therefore dispensable, and mutations in a single gene can be compensated by function of a similar cell adhesion gene. Other organs that are not fundamental to life, such as the ear, may not express compensatory mechanisms and therefore have a phenotype when single genes are mutated. However, this contrasts with the high prevalence of autosomal dominant diseases in other organs.

Do Cell Junction Protein Mutations Cause an Airway Phenotype in Mice or Humans?

We have presented an argument that mutations in cell junction and adhesion genes rarely produce a pulmonary phenotype in mouse knockout models and do not produce an obvious pulmonary phenotype in humans through a comprehensive review of human genotype-phenotype and expression data. It would be presumptive to assume that because a pulmonary phenotype is not obvious in humans, cell junction and adhesion molecules are not important in the airway. In fact, the mouse knockout literature highlights that the pulmonary phenotype may be subtle and require challenges to the lung to manifest itself.

Our research suggests that simply because a cell junction or adhesion protein is expressed in an organ does not imply that it will exhibit a drastic phenotype when mutated. One explanation is that because a functioning lung is critical to survival, redundancy in the system is expected. Therefore, mutations in a single gene might be compensated by a related function of a similar gene product. Further studies in human and animal models will help us understand the pathogenesis and overlap in the function of cell junction and adhesion gene products. Finally, it is possible that the human lung phenotype is subtle and has not yet been described. We encourage clinicians and researchers to become aware of the breadth of the field of cell adhesion, encourage exploratory study, and develop a keen eye to identify possible pulmonary phenotypes so we can improve the care of our patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the help and critical review of this paper by Dr. David Stoltz, Dr. Paul McCray, Dr. John Englehardt, Dr. Alejandro Comellas and Dr. Michael Welsh. We also thank Todd E. Scheetz, Geri L. Traver, Paul B. McCray, Phil Karp and the University of Iowa cell culture core.

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL91842 and HL51670), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (R458 and ENGLH9850), a T32 post-doctoral pulmonary training grant (EHC), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Diseases and Kidney Diseases (DK54759).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0498TR on February 4, 2011

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Smith JJ, Karp PH, Welsh MJ. Defective fluid transport by cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J Clin Invest 1994;93:1307–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King LS, Nielsen S, Agre P, Brown RH. Decreased pulmonary vascular permeability in aquaporin-1-null humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:1059–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaedel C, Marthinsen L, Kristoffersson AC, Kornfalt R, Nilsson KO, Orlenius B, Holmberg L. Lung symptoms in pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 are associated with deficiency of the alpha-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. J Pediatr 1999;135:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cereijido M, Contreras RG, Flores-Benítez D, Flores-Maldonado C, Larre I, Ruiz A, Shoshani L. New diseases derived or associated with the tight junction. Arch Med Res 2007;38:465–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu Rev Physiol 2006;68:403–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol 1993;123:1777–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saitou M, Furuse M, Sasaki H, Schulzke JD, Fromm M, Takano H, Noda T, Tsukita S. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell 2000;11:4131–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikenouchi J, Furuse M, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Tricellulin constitutes a novel barrier at tricellular contacts of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 2005;171:939–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox ER, Burton QL, Naz S, Riazuddin S, Smith TN, Ploplis B, Belyantseva I, Ben-Yosef T, Liburd NA, Morell RJ, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding tight junction claudin-14 cause autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29. Cell 2001;104:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Yosef T. Claudin 14 knockout mice, a model for autosomal recessive deafness DFNB29, are deaf due to cochlear hair cell degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:2049–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon DB. Paracellin-1, a renal tight junction protein required for paracellular mg2+ resorption. Science 1999;285:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niessen CM. Tight junctions/adherens junctions: basic structure and function. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:2525–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Excoffon KJDA, Gansemer N, Traver G, Zabner J. Functional effects of Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor glycosylation on homophilic adhesion and adenoviral infection. J Virol 2007;81:5573–5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebnet K, Suzuki A, Ohno S, Vestweber D. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMS): more molecules with dual functions? J Cell Sci 2004;117:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, Taite H, Scoular R, Miller A, Reeve AE. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature 1998;392:402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winter MC, Shasby SS, Ries DR, Shasby DM. Par2 activation interrupts E-cadherin adhesion and compromises the airway epithelial barrier: protective effect of beta-agonists. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L628–L635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Douglas IS, Diaz del Valle F, Winn RA, Voelkel NF. Beta-catenin in the fibroproliferative response to acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:274–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suriano G, Oliveira MJ, Huntsman D, Mateus AR, Ferreira P, Casares F, Oliveira C, Carneiro F, Machado JC, Mareel M, et al. E-cadherin germline missense mutations and cell phenotype: Evidence for the independence of cell invasion on the motile capabilities of the cells. Hum Mol Genet 2003;12:3007–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrod DR, Merritt AJ, Nie Z. Desmosomal adhesion: structural basis, molecular mechanism and regulation. Mol Membr Biol 2002;19:81–94. (review). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGrath JA, McMillan JR, Shemanko CS, Runswick SK, Leigh IM, Lane EB, Garrod DR, Eady RA. Mutations in the plakophilin 1 gene result in ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome. Nat Genet 1997;17:240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rickman L, Simrak D, Stevens HP, Hunt DM, King IA, Bryant SP, Eady RA, Leigh IM, Arnemann J, Magee AI, et al. N-terminal deletion in a desmosomal cadherin causes the autosomal dominant skin disease striate palmoplantar keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green KJ, Jones JC. Desmosomes and hemidesmosomes: structure and function of molecular components. FASEB J 1996;10:871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burridge K, Fath K, Kelly T, Nuckolls G, Turner C. Focal adhesions: transmembrane junctions between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Biol 1988;4:487–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano A, Chao S-C, Pulkkinen L, Murrell D, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Pfendner E, Uitto J. Laminin 5 mutations in junctional epidermolysis bullosa: molecular basis of Herlitz vs. non-Herlitz phenotypes. Hum Genet 2002;110:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnaout MA, Dana N, Gupta SK, Tenen DG, Fathallah DM. Point mutations impairing cell surface expression of the common beta subunit (cd18) in a patient with leukocyte adhesion molecule (leu-cam) deficiency. J Clin Invest 1990;85:977–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wardlaw AJ, Hibbs ML, Stacker SA, Springer TA. Distinct mutations in two patients with leukocyte adhesion deficiency and their functional correlates. J Exp Med 1990;172:335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheppard D. In vivo functions of integrins: lessons from null mutations in mice. Matrix Biol 2000;19:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheppard D. Functions of pulmonary epithelial integrins: from development to disease. Physiol Rev 2003;83:673–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang EH, Van Camp G, Smith RJ. The role of connexins in human disease. Ear Hear 2003;24:314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelsell DP, Dunlop J, Stevens HP, Lench NJ, Liang JN, Parry G, Mueller RF, Leigh IM. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature 1997;387:80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berglund L, Bjorling E, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, Asplund A, Szigyarto CA, Persson A, Ottosson J, Wernerus H, Nilsson P, et al. A genecentric human protein atlas for expression profiles based on antibodies. Mol Cell Proteomics 2008;7:2019–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pezzulo AA, Starner TD, Scheetz TE, Traver GL, Tilley AE, Harvey BG, Crystal RG, McCray PB, Jr., Zabner J. The air-liquid interface and use of primary cell cultures are important to recapitulate the transcriptional profile of in vivo airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2011;300:L25–L31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karp PH, Moninger TO, Weber SP, Nesselhauf TS, Launspach JL, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. An in vitro model of differentiated human airway epithelia. Methods for establishing primary cultures. Methods Mol Biol 2002;188:115–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hynes RO. Targeted mutations in cell adhesion genes: what have we learned from them? Dev Biol 1996;180:402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Arcangelis A, Mark M, Kreidberg J, Sorokin L, Georges-Labouesse E. Synergistic activities of alpha3 and alpha6 integrins are required during apical ectodermal ridge formation and organogenesis in the mouse. Development 1999;126:3957–3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamin JT, Gaston DC, Halloran BA, Schnapp LM, Zent R, Prince LS. The role of integrin alpha8beta1 in fetal lung morphogenesis and injury. Dev Biol 2009;335:407–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Symons JM, Goldstein SL, McDonald A, Miner JH, Kreidberg JA. (alpha)3(beta)1 integrin regulates epithelial cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Sci 1999;112:2925–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imhof BA, Zimmerli C, Gliki G, Ducrest-Gay D, Juillard P, Hammel P, Adams R, Aurrand-Lions M. Pulmonary dysfunction and impaired granulocyte homeostasis result in poor survival of JAM-C-deficient mice. J Pathol 2007;212:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet JF, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay MA, et al. The integrin alpha V beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: A mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 1999;96:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H, Rodgers JR, Perrard X-YD, Perrard JL, Prince JE, Abe Y, Davis BK, Dietsch G, Smith CW, Ballantyne CM. Deficiency of CD11B or CD11D results in reduced staphylococcal enterotoxin-induced T cell response and T cell phenotypic changes. J Immunol 2004;173:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hogmalm A, Sheppard D, Lappalainen U, Bry K. Beta6 integrin subunit deficiency alleviates lung injury in a mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010;43:88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang XZ, Wu JF, Ferrando R, Lee JH, Wang YL, Farese RV, Sheppard D. Fatal bilateral chylothorax in mice lacking the integrin alpha9beta1. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:5208–5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen NM, Pulkkinen L, Schlueter JA, Meneguzzi G, Uitto J, Senior RM. Lung development in laminin gamma2 deficiency: abnormal tracheal hemidesmosomes with normal branching morphogenesis and epithelial differentiation. Respir Res 2006;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadj-Rabia S, Baala L, Vabres P, Hamel-Teillac D, Jacquemin E, Fabre M, Lyonnet S, De Prost Y, Munnich A, Hadchouel M, et al. Claudin-1 gene mutations in neonatal sclerosing cholangitis associated with ichthyosis: a tight junction disease. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1386–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldmeyer L, Huber M, Fellmann F, Beckmann JS, Frenk E, Hohl D. Confirmation of the origin of nisch syndrome. Hum Mutat 2006;27:408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, Yoshida Y, Haratake A, Sugitani Y, Noda T, Kubo A, Tsukita S. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2002;156:1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nitta T. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2003;161:653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakano Y, Kim SH, Kim HM, Sanneman JD, Zhang Y, Smith RJ, Marcus DC, Wangemann P, Nessler RA, Banfi B. A claudin-9-based ion permeability barrier is essential for hearing. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gow A, Southwood CM, Li JS, Pariali M, Riordan GP, Brodie SE, Danias J, Bronstein JM, Kachar B, Lazzarini RA. CNS myelin and sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in OSP/claudin-11 null mice. Cell 1999;99:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wattenhofer M, Reymond A, Falciola V, Charollais A, Caille D, Borel C, Lyle R, Estivill X, Petersen MB, Meda P, et al. Different mechanisms preclude mutant CLDN14 proteins from forming tight junctions in vitro. Hum Mutat 2005;25:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber S, Schneider L, Peters M, Misselwitz J, Rönnefarth G, Böswald M, Bonzel KE, Seeman T, Suláková T, Kuwertz-Bröking E, et al. Novel paracellin-1 mutations in 25 families with familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:1872–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Müller D, Kausalya PJ, Claverie-Martin F, Meij IC, Eggert P, Garcia-Nieto V, Hunziker W. A novel claudin 16 mutation associated with childhood hypercalciuria abolishes binding to ZO-1 and results in lysosomal mistargeting. Am J Hum Genet 2003;73:1293–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himmerkus N, Shan Q, Goerke B, Hou J, Goodenough DA, Bleich M. Salt and acid-base metabolism in claudin-16 knockdown mice: impact for the pathophysiology of FHHNC patients. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;295:F1641–F1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Konrad M, Schaller A, Seelow D, Pandey AV, Waldegger S, Lesslauer A, Vitzthum H, Suzuki Y, Luk JM, Becker C, et al. Mutations in the tight-junction gene claudin 19 (CLDN19) are associated with renal magnesium wasting, renal failure, and severe ocular involvement. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyamoto T. Tight junctions in Schwann cells of peripheral myelinated axons: a lesson from claudin-19-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2005;169:527–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Fanning AS, Lagziel A, Kitajiri S, Ramzan K, Khan SN, Chattaraj P, Friedman PL, Anderson J, et al. Tricellulin is a tight-junction protein necessary for hearing. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:1040–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chishti MS, Bhatti A, Tamim S, Lee K, McDonald ML, Leal SM, Ahmad W. Splice-site mutations in the tric gene underlie autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment in Pakistani families. J Hum Genet 2008;53:101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carlton V, Harris B, Puffenberger E, Batta A, Knisely A, Robinson D, Strauss K, Shneider B, Lim W, Salen G, et al. Complex inheritance of familial hypercholanemia with associated mutations in TJP2 and BAAT. Nat Genet 2003;34:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu J, Kausalya PJ, Phua DC, Ali SM, Hossain Z, Hunziker W. Early embryonic lethality of mice lacking ZO-2, but not ZO-3, reveals critical and nonredundant roles for individual zonula occludens proteins in mammalian development. Mol Cell Biol 2008;28:1669–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cera M. Increased DC trafficking to lymph nodes and contact hypersensitivity in junctional adhesion molecule-a-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 2004;114:729–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asher DR, Cerny AM, Weiler SR, Horner JW, Keeler ML, Neptune MA, Jones SN, Bronson RT, Depinho RA, Finberg RW. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is essential for cardiomyocyte development. Genesis 2005;42:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhadanov AB, Provance DW, Speer CA, Coffin JD, Goss D, Blixt JA, Reichert CM, Mercer JA. Absence of the tight junctional protein AF-6 disrupts epithelial cell-cell junctions and cell polarity during mouse development. Curr Biol 1999;9:880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suzuki K, Hu D, Bustos T, Zlotogora J, Richieri-Costa A, Helms JA, Spritz RA. Mutations of PVRL1, encoding a cell-cell adhesion molecule/herpesvirus receptor, in cleft lip/palate-ectodermal dysplasia. Nat Genet 2000;25:427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richards FM, McKee SA, Rajpar MH, Cole TR, Evans DG, Jankowski JA, McKeown C, Sanders DS, Maher ER. Germline E-cadherin gene (CDH1) mutations predispose to familial gastric cancer and colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gayther SA, Gorringe KL, Ramus SJ, Huntsman D, Roviello F, Grehan N, Machado JC, Pinto E, Seruca R, Halling K, et al. Identification of germ-line E-cadherin mutations in gastric cancer families of European origin. Cancer Res 1998;58:4086–4089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oliveira C, Bordin MC, Grehan N, Huntsman D, Suriano G, Machado JC, Kiviluoto T, Aaltonen L, Jackson CE, Seruca R, et al. Screening E-cadherin in gastric cancer families reveals germline mutations only in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer kindred. Hum Mutat 2002;19:510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yabuta T, Shinmura K, Tani M, Yamaguchi S, Yoshimura K, Katai H, Nakajima T, Mochiki E, Tsujinaka T, Takami M, et al. E-cadherin gene variants in gastric cancer families whose probands are diagnosed with diffuse gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2002;101:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frebourg T, Oliveira C, Hochain P, Karam R, Manouvrier S, Graziadio C, Vekemans M, Hartmann A, Baert-Desurmont S, Alexandre C, et al. Cleft lip/palate and CDH1/E-cadherin mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. J Med Genet 2006;43:138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larue L, Ohsugi M, Hirchenhain J, Kemler R. E-cadherin null mutant embryos fail to form a trophectoderm epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:8263–8267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Radice GL, Rayburn H, Matsunami H, Knudsen KA, Takeichi M, Hynes RO. Developmental defects in mouse embryos lacking N-cadherin. Dev Biol 1997;181:64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sprecher E, Bergman R, Richard G, Lurie R, Shalev S, Petronius D, Shalata A, Anbinder Y, Leibu R, Perlman I, et al. Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy is caused by a mutation in CDH3, encoding P-cadherin. Nat Genet 2001;29:134–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Indelman M, Bergman R, Lurie R, Richard G, Miller B, Petronius D, Ciubutaro D, Leibu R, Sprecher E. A missense mutation in CDH3, encoding P-cadherin, causes hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy. J Invest Dermatol 2002;119:1210–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kjaer KW, Hansen L, Schwabe GC, Marques-de-Faria AP, Eiberg H, Mundlos S, Tommerup N, Rosenberg T. Distinct CDH3 mutations cause ectodermal dysplasia, ectrodactyly, macular dystrophy (EEM syndrome). J Med Genet 2005;42:292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Radice GL, Ferreira-Cornwell MC, Robinson SD, Rayburn H, Chodosh LA, Takeichi M, Hynes RO. Precocious mammary gland development in P-cadherin-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 1997;139:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez-Moreno M, Davis MA, Wong E, Pasolli HA, Reynolds AB, Fuchs E. P120-catenin mediates inflammatory responses in the skin. Cell 2006;124:631–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vasioukhin V, Bauer C, Degenstein L, Wise B, Fuchs E. Hyperproliferation and defects in epithelial polarity upon conditional ablation of alpha-catenin in skin. Cell 2001;104:605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hajra K, Fearon E. Cadherin and catenin alterations in human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2002;34:255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haegel H, Larue L, Ohsugi M, Fedorov L, Herrenknecht K, Kemler R. Lack of beta-catenin affects mouse development at gastrulation. Development 1995;121:3529–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chidgey M. Mice lacking desmocollin 1 show epidermal fragility accompanied by barrier defects and abnormal differentiation. J Cell Biol 2001;155:821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Syrris P, Ward D, Evans A, Asimaki A, Gandjbakhch E, Sen-Chowdhry S, McKenna WJ. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in the desmosomal gene desmocollin-2. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:978–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heuser A, Plovie ER, Ellinor PT, Grossmann KS, Shin JT, Wichter T, Basson CT, Lerman BB, Sasse-Klaassen S, Thierfelder L, et al. Mutant desmocollin-2 causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Den Z, Cheng X, Merched-Sauvage M, Koch PJ. Desmocollin 3 is required for pre-implantation development of the mouse embryo. J Cell Sci 2006;119:482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Awad MM, Dalal D, Cho E, Amat-Alarcon N, James C, Tichnell C, Tucker A, Russell SD, Bluemke DA, Dietz HC, et al. DSG2 mutations contribute to arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pilichou K, Nava A, Basso C, Beffagna G, Bauce B, Lorenzon A, Frigo G, Vettori A, Valente M, Towbin J, et al. Mutations in desmoglein-2 gene are associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2006;113:1171–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Syrris P, Ward D, Asimaki A, Evans A, Sen-Chowdhry S, Hughes SE, McKenna WJ. Desmoglein-2 mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a genotype-phenotype characterization of familial disease. Eur Heart J 2007;28:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eshkind L, Tian Q, Schmidt A, Franke WW, Windoffer R, Leube RE. Loss of desmoglein 2 suggests essential functions for early embryonic development and proliferation of embryonal stem cells. Eur J Cell Biol 2002;81:592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koch PJ, Mahoney MG, Ishikawa H, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, Shultz L, Murphy GF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Stanley JR. Targeted disruption of the pemphigus vulgaris antigen (desmoglein 3) gene in mice causes loss of keratinocyte cell adhesion with a phenotype similar to pemphigus vulgaris. J Cell Biol 1997;137:1091–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kljuic A, Bazzi H, Sundberg JP, Martinez-Mir A, O'Shaughnessy R, Mahoney MG, Levy M, Montagutelli X, Ahmad W, Aita VM, et al. Desmoglein 4 in hair follicle differentiation and epidermal adhesion: evidence from inherited hypotrichosis and acquired pemphigus vulgaris. Cell 2003;113:249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Armstrong DK, McKenna KE, Purkis PE, Green KJ, Eady RA, Leigh IM, Hughes AE. Haploinsufficiency of desmoplakin causes a striate subtype of palmoplantar keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rampazzo A, Nava A, Malacrida S, Beffagna G, Bauce B, Rossi V, Zimbello R, Simionati B, Basso C, Thiene G, et al. Mutation in human desmoplakin domain binding to plakoglobin causes a dominant form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71:1200–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whittock NV, Wan H, Morley SM, Garzon MC, Kristal L, Hyde P, McLean WH, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, Christiano AM, et al. Compound heterozygosity for non-sense and mis-sense mutations in desmoplakin underlies skin fragility/woolly hair syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jonkman MF, Pasmooij AM, Pasmans SG, van den Berg MP, Ter Horst HJ, Timmer A, Pas HH. Loss of desmoplakin tail causes lethal acantholytic epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet 2005;77:653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Uzumcu A, Norgett EE, Dindar A, Uyguner O, Nisli K, Kayserili H, Sahin SE, Dupont E, Severs NJ, Leigh IM, et al. Loss of desmoplakin isoform I causes early onset cardiomyopathy and heart failure in a naxos-like syndrome. J Med Genet 2006;43:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang Z, Bowles NE, Scherer SE, Taylor MD, Kearney DL, Ge S, Nadvoretskiy VV, DeFreitas G, Carabello B, Brandon LI, et al. Desmosomal dysfunction due to mutations in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2006;99:646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Norgett EE, Hatsell SJ, Carvajal-Huerta L, Cabezas JC, Common J, Purkis PE, Whittock N, Leigh IM, Stevens HP, Kelsell DP. Recessive mutation in desmoplakin disrupts desmoplakin-intermediate filament interactions and causes dilated cardiomyopathy, woolly hair and keratoderma. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:2761–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gallicano GI, Bauer C, Fuchs E. Rescuing desmoplakin function in extra-embryonic ectoderm reveals the importance of this protein in embryonic heart, neuroepithelium, skin and vasculature. Development 2001;128:929–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gallicano GI, Kouklis P, Bauer C, Yin M, Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. Desmoplakin is required early in development for assembly of desmosomes and cytoskeletal linkage. J Cell Biol 1998;143:2009–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Whittock NV, Haftek M, Angoulvant N, Wolf F, Perrot H, Eady RA, McGrath JA. Genomic amplification of the human plakophilin 1 gene and detection of a new mutation in ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, Paul M, Basson CT, McDermott DA, Lerman BB, Markowitz SM, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet 2004;36:1162–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grossmann KS, Grund C, Huelsken J, Behrend M, Erdmann B, Franke WW, Birchmeier W. Requirement of plakophilin 2 for heart morphogenesis and cardiac junction formation. J Cell Biol 2004;167:149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McKoy G, Protonotarios N, Crosby A, Tsatsopoulou A, Anastasakis A, Coonar A, Norman M, Baboonian C, Jeffery S, McKenna WJ. Identification of a deletion in plakoglobin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with palmoplantar keratoderma and woolly hair (naxos disease). Lancet 2000;355:2119–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Asimaki A, Syrris P, Wichter T, Matthias P, Saffitz JE, McKenna WJ. A novel dominant mutation in plakoglobin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:964–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McGrath JA, Gatalica B, Christiano AM, Li K, Owaribe K, McMillan JR, Eady RA, Uitto J. Mutations in the 180-KD bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG2), a hemidesmosomal transmembrane collagen (COL17A1), in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet 1995;11:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gatalica B, Pulkkinen L, Li K, Kuokkanen K, Ryynänen M, McGrath JA, Uitto J. Cloning of the human type XVII collagen gene (COL17A1), and detection of novel mutations in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:352–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jonkman MF, de Jong MC, Heeres K, Pas HH, van der Meer JB, Owaribe K, Martinez de Velasco AM, Niessen CM, Sonnenberg A. 180-KD bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP180) is deficient in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1345–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schumann H, Hammami-Hauasli N, Pulkkinen L, Mauviel A, Küster W, Lüthi U, Owaribe K, Uitto J, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Three novel homozygous point mutations and a new polymorphism in the COL17A1 gene: relation to biological and clinical phenotypes of junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:1344–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chavanas S, Gache Y, Tadini G, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, Ortonne JP, Meneguzzi G. A homozygous in-frame deletion in the collagenous domain of bullous pemphigoid antigen BP180 (type XVII collagen) causes generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 1997;109:74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Darling TN, Koh BB, Bale SJ, Compton JG, Bauer JW, Hintner H, Yancey KB. A deletion mutation in COL17A1 in five Austrian families with generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa represents propagation of an ancestral allele. J Invest Dermatol 1998;110:170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Floeth M, Fiedorowicz J, Schacke H, Hammami-Hausli N, Owaribe K, Trueb RM, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Novel homozygous and compound heterozygous COL17A1 mutations associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol 1998;111:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tasanen K, Floeth M, Schumann H, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Hemizygosity for a glycine substitution in collagen XVII: unfolding and degradation of the ectodomain. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith FJ, Eady RA, Leigh IM, McMillan JR, Rugg EL, Kelsell DP, Bryant SP, Spurr NK, Geddes JF, Kirtschig G, et al. Plectin deficiency results in muscular dystrophy with epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet 1996;13:450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pulkkinen L, Smith FJ, Shimizu H, Murata S, Yaoita H, Hachisuka H, Nishikawa T, McLean WH, Uitto J. Homozygous deletion mutations in the plectin gene (PLEC1) in patients with epidermolysis bullosa simplex associated with late-onset muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 1996;5:1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.McLean WH, Pulkkinen L, Smith FJ, Rugg EL, Lane EB, Bullrich F, Burgeson RE, Amano S, Hudson DL, Owaribe K, et al. Loss of plectin causes epidermolysis bullosa with muscular dystrophy: cDNA cloning and genomic organization. Genes Dev 1996;10:1724–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koss-Harnes D, Høyheim B, Anton-Lamprecht I, Gjesti A, Jørgensen RS, Jahnsen FL, Olaisen B, Wiche G, Gedde-Dahl T. A site-specific plectin mutation causes dominant epidermolysis bullosa simplex ogna: two identical de novo mutations. J Invest Dermatol 2002;118:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Charlesworth A, Gagnoux-Palacios L, Bonduelle M, Ortonne JP, De Raeve L, Meneguzzi G. Identification of a lethal form of epidermolysis bullosa simplex associated with a homozygous genetic mutation in plectin. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:1344–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nakamura H, Sawamura D, Goto M, Nakamura H, McMillan JR, Park S, Kono S, Hasegawa S, Paku S, Nakamura T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex associated with pyloric atresia is a novel clinical subtype caused by mutations in the plectin gene (plec1). J Mol Diagn 2005;7:28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pfendner E, Uitto J. Plectin gene mutations can cause epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. J Invest Dermatol 2005;124:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]