Abstract

Chlorine gas (Cl2) exposure during accidents or in the military setting results primarily in injury to the lungs. However, the potential for Cl2 exposure to promote injury to the systemic vasculature leading to compromised vascular function has not been studied. We hypothesized that Cl2 promotes extrapulmonary endothelial dysfunction characterized by a loss of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-derived signaling. Male Sprague Dawley rats were exposed to Cl2 for 30 minutes, and eNOS-dependent vasodilation of aorta as a function of Cl2 dose (0–400 ppm) and time after exposure (0–48 h) were determined. Exposure to Cl2 (250–400 ppm) significantly inhibited eNOS-dependent vasodilation (stimulated by acetycholine) at 24 to 48 hours after exposure without affecting constriction responses to phenylephrine or vasodilation responses to an NO donor, suggesting decreased NO formation. Consistent with this hypothesis, eNOS protein expression was significantly decreased (∼ 60%) in aorta isolated from Cl2–exposed versus air-exposed rats. Moreover, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA was up-regulated in circulating leukocytes and aorta isolated 24 hours after Cl2 exposure, suggesting stimulation of inflammation in the systemic vasculature. Despite decreased eNOS expression and activity, no changes in mean arterial blood pressure were observed. However, injection of 1400W, a selective inhibitor of iNOS, increased mean arterial blood pressure only in Cl2–exposed animals, suggesting that iNOS-derived NO compensates for decreased eNOS-derived NO. These results highlight the potential for Cl2 exposure to promote postexposure systemic endothelial dysfunction via disruption of vascular NO homeostasis mechanisms.

Keywords: endothelium, nitric oxide, inflammation, inhaled reactive oxidants

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

Data presented in this study shows that chlorine gas toxicity comprises not only lung injury, but systemic vascular endothelial injury characterized by loss of endothelial nitric oxide synthase derived nitric oxide bioactivity. In addition, chlorine gas increased systemic inflammation characterized by induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Taken together these data demonstrate the potential for vascular inflammation and dysfunction in post chlorine gas toxicity with disruption of nitric oxide homeostasis as a central mechanism.

Chlorine gas (Cl2) is used extensively in a wide variety of manufacturing processes and ranks among the leading chemicals transported by rail in close proximity to major population centers. As such, Cl2–induced toxicity is a concern and is exemplified by many cases worldwide of accidental exposure secondary to train derailment (1–3). This, coupled with the continual use of Cl2 in military warfare and exposure in the home (secondary to mishandling of bleach) (4–6), has led to recent interest into a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms of Cl2–induced toxicity (7).

The lungs are primary targets of Cl2 toxicity, with the initial injury that occurs during exposure being dependent on the dose of Cl2 and length of exposure. This initial injury is thought to be mediated largely through direct reactions of Cl2 with biomolecules and via secondary (to Cl2 hydrolysis) generation of hypochlorous acid (HOCl). We have demonstrated that exposure of rats and mice to Cl2 leads to extensive injury to airway and alveolar lung epithelia, decreased surfactant function, decreased ability of alveolar epithelial cells to actively transport sodium ions and clear fluid, and decreased levels of ascorbate and a decreased ratio of glutathione to oxidized glutathione in BAL and lung tissues (8–10). These inflammatory responses continue to induce injury after cessation of Cl2 exposure, culminating in acute lung injury, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and reactive airway syndrome (9, 11–17). The precise mechanism of this post-Cl2 exposure injury remains unclear and important to address because this aspect of Cl2–induced injury is the primary goal for therapies. Recent studies suggest that post-Cl2–induced acute lung injury is mediated by inflammation and the reactivity of a variety of reactive oxygen, reactive nitrogen, and reactive chlorine species (9, 15).

Less is known on the potential for Cl2 to induce injury to extrapulmonary tissues and specifically to the extrapulmonary/systemic vasculature. Recent studies have demonstrated a role for dysfunction in vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) signaling in mediating increased susceptibility to cardiovascular disease in response to environmental exposure to inhaled species that can promote oxidative tissue injury (e.g., cigarette smoke, diesel, or ozone) (18–21). Nitric oxide produced from eNOS plays a central role in vascular homeostasis mechanisms, including regulating vessel tone and cellular respiration, inhibiting smooth muscle proliferation, and maintaining an antithrombotic and antiinflammatory luminal surface (22, 23). Therefore, dysfunction in eNOS-derived NO signaling predisposes the vasculature to the development of inflammatory disease, and its functional assessment is now considered a key parameter in the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (24, 25). The mechanisms by which inhaled reactive oxidant species promote extrapulmonary injury remain unclear. Because of their reactivity, Cl2 and HOCl react with biomolecules in the epithelial lining fluid or cell surface (26). Thus, injury to extrapulmonary tissues suggests production of secondary intermediates that are diffusible and longer lived. The potential for exposure to Cl2 acutely to promote vascular endothelial dysfunction has not been explored. Cl2 is an interesting example because endogenously reactive chlorine species (including HOCl and Cl2) formed during inflammation have been closely linked with the development of atherosclerosis through multiple mechanisms, including eNOS inhibition (27–38). In this study, we present data showing that exposure of rats to Cl2 under conditions that result in lung injury similar to that seen with humans during accidental or deliberate release of Cl2 into the atmosphere (9, 39–41) causes a postexposure injury to the extrapulmonary vasculature that is mediated via inhibition of eNOS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed materials and methods are provided in the online supplement.

Unless stated otherwise, all reagents and antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and AbCam (Cambridge, MA), respectively, except Mahma/NONOate (MNO), which was purchased from Axxora Platform (San Diego, CA). Male Sprague Dawley rats (200–300 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and kept on 12-hour light/dark cycles with access to standard chow and water ad libitum before and after chlorine exposure. 1400W was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences International, Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Rat Exposure to Cl2

Whole body exposure of rats to different doses of Cl2 was performed as previously described (9). Two rats were exposed in the same chamber at any one time. All exposures were performed between 08:00 and 09:00 and were 30 minutes in length and followed by return to room air. Age-matched controls included rats exposed to air only. All experiments involving animals were conducted according to protocols approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Aortic Vessel Studies

At the indicated times after Cl2 exposure, aortas were collected, and responses to the indicated vasoconstrictive and vasoactive stimuli were determined in vessel bioassay chambers (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA) as previously described (42). All vessel bioassay studies were performed in vessels pretreated with indomethacin (5 μM) and in Krebs Henseleit buffer perfused with 21%O2, 5%CO2 balanced with N2.

NOS Expression

Expression of eNOS, inducible NOS (iNOS), or neuronal NOS (nNOS) mRNA in the aorta or iNOS in circulating leukocytes was assessed by real-time PCR as previously described (43). Western blotting and immunofluoresence staining and quantitation of eNOS protein were determined as described in the online supplement.

Nitrite Measurement

Plasma nitrite was measured as previously described (42).

Measurement of Cytokines

IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α were measured using a sandwich immunoassay kit (K11014A-4; Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Detection limits for IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α were 9.77, 15.7, and 5.78 pg/ml, respectively.

Blood Pressure Measurements

Hemodynamic parameters were measured noninvasively using a specialized differential pressure transducer tail cuff (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Rats were acclimated to the blood pressure measuring apparatus following manufacturer recommendations to obtain steady baseline values. Upon reaching stable baseline readings, rats were exposed to Cl2. Hemodynamic parameters were measured at different times after exposure as indicated.

RESULTS

Effects of Cl2 on Aortic Responses to Phenylephrine and Acetycholine

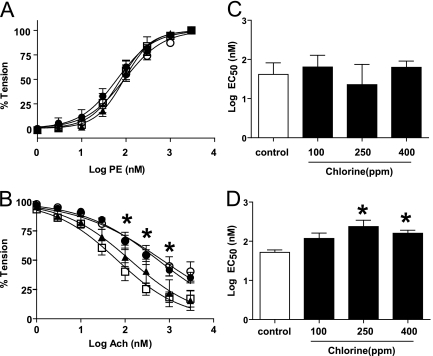

To test the hypothesis that chlorine exposure inhibits systemic vascular eNOS signaling, aorta were collected from rats at different times (6, 24, and 48 h) after Cl2 exposure (400 ppm, 30 min), and vasoconstrictive responses to phenylephrine (PE) and vasodilatory responses to acetycholine (Ach) were determined. Figure 1A shows similar PE dose-dependent vasoconstriction in aorta isolated from Cl2–exposed animals at various times after exposure as compared with air-exposed control animals (time = 0 h). However, Ach-dependent dilation was significantly inhibited at 24 and 48 hours after Cl2 exposure (Figure 1B). Next, the effects on aorta responses to PE and Ach 24 hours after exposure of rats to different doses of Cl2 were determined. Figure 1C shows that PE-induced vasoconstriction was not affected at any Cl2 dose used. However, as shown by increases in the EC50, Ach-induced vasodilation was significantly inhibited by preexposure to 250 or 400 ppm Cl2 but not to 100 ppm Cl2 (Figure 1D). Based on these data, further experiments were performed on aorta isolated from rats 24 hours after exposure to Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). These Cl2 exposure conditions result in significant and sustained hypoxemia and hypercapnia as well as depletion of lung ascorbate, which mimic injury observed in human incidences of Cl2 exposure (39).

Figure 1.

Chlorine gas (Cl2) exposure inhibits aortic vasodilation in response to acetylcholine. Rats were exposed to air (open squares) or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). Aorta were isolated at 6 (closed triangles), 24 (closed circles), or 48 hours (open circles) thereafter, and vasoconstriction and vasodilation responses to phenylephrine (PE) (A) or acetycholine (Ach) (B), respectively, were determined. Data are means ± SEM for cumulative dose-dependent changes in tension. *P < 0.05 by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for 24 and 48 hours after Cl2 exposure relative to control (n = 3–12). (C and D) EC50 values for PE-dependent vasoconstriction and Ach-dependent vasodilation, respectively, in aorta isolated from rats 24 hours after exposure to different doses of Cl2 (0–400 ppm) for 30 minutes. Data show mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test relative to control (n = 5–11).

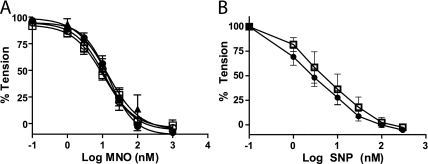

To evaluate the potential mechanisms for compromised eNOS-dependent signaling in the aorta, we hypothesized that formation of reactive oxygen species (e.g., superoxide anion or lipid radicals) was increased. These reactive oxygen species would rapidly scavenge NO and inhibit subsequent relaxation analogous to previously reported mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction (44–46). To test this hypothesis, aorta responses to the NO donors MNO or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were assessed. Figure 2 shows MNO- and SNP-induced vasodilation in a dose-dependent manner to similar extents in aorta isolated from air- or Cl2–exposed rats, indicating that increased ROS did not mediate altered eNOS-dependent vasodilation. Because these NO donors are endothelial-independent vasodilators, these data also indicate that dysfunctional Ach-induced vasodilation is mediated via reactions upstream of NO-dependent activation of soluble guanylate cyclase and do not involve dysfunctional smooth muscle responses.

Figure 2.

Cl2 exposure does not affect Mahma/NONOate (MNO)- or sodium nitroprusside (SNP)-induced vasodilation of aorta. Rats were exposed to air (open squares) or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). Aorta were isolated at 6 (closed triangles), 24 (closed circles), or 48 hours (open circles) thereafter, and vasodilation responses to the NO donors MNO (A) or SNP (B) were determined. Data show mean ± SEM. No significant differences were observed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test (n = 3–8).

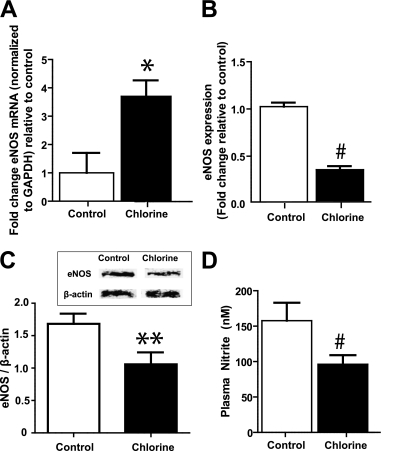

Cl2 Exposure Decreases eNOS Protein Expression and Markers of eNOS Activity

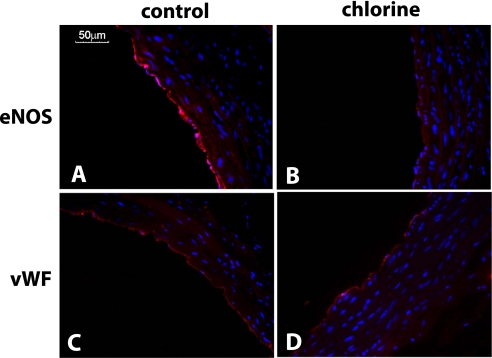

We next tested if decreased Ach-dependent vasodilation was attributed to altered NOS expression. Figure 3A shows that there was a significant increase in eNOS mRNA levels in aorta from Cl2–exposed versus control rats. However, protein expression was decreased by approximately 40 to 60%, as determined by immunofluorescence or Western blotting (Figures 3B, 3C, and 4). This decrease in eNOS was not due to a loss of the endothelial monolayer indicated by similar levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF) expression in both experimental groups (Figures 4C and 4D). Figure 3C shows that plasma levels of nitrite, a selective marker of eNOS activity, were also decreased in Cl2–exposed rats.

Figure 3.

Effects of Cl2 on aortic endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression eNOS mRNA (A) or protein (B and C) were determined in aorta isolated from rats 24 hours after exposure to air or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). eNOS protein levels were determined by immunoflouresence (B) or by Western blotting (C; inset shows representative Western blots). Data show mean ± SEM (n = 3–4). **P < 0.05, *P < 0.03, and #P < 0.001 relative to control. (D) Plasma nitrite concentrations in 24 hours after air or Cl2 exposure. Data show mean ± SEM (n = 5–7). #P < 0.05 relative to control.

Figure 4.

Cl2 decreases eNOS protein expression. Representative immunofluoresence images for eNOS (A and B) or von Willebrand factor (vWF) (C and D) staining from aorta collected 24 hours after exposure to air (A and C) or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min) (B and D). Red = eNOS or vWF as indicated; blue = Hoechst staining for nuclei.

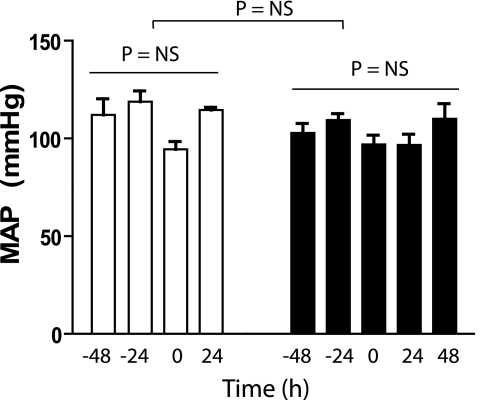

Effect of Cl2 on Systemic Hemodynamics

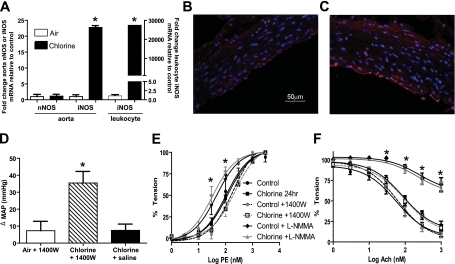

Many studies have shown that inhibited eNOS-dependent vasodilation results in increased blood pressure. The effects of Cl2 exposure on parameters that regulate hemodynamics were therefore measured by tail cuff plethysmography. No change in MAP was observed in rats measured up to 48 hours after Cl2 exposure (Figure 5). Similarly, no change in heart rate or tail blood flow was observed (not shown). These data suggest that Cl2 exposure affects additional pathways that counter the loss of eNOS-dependent function, which maintains vascular tone. Previous studies have shown that Cl2 exposure increases iNOS expression in the lung (15), although this is likely dependent on exposure conditions because a recent study using a longer-duration but lower Cl2 dose failed to observe changes in iNOS levels in the lung (17). iNOS is induced during inflammation and when elevated in the circulation/systemic vasculature is associated with hypotension. We tested if Cl2 exposure increases iNOS in extrapulmonary tissues and whether iNOS-derived NO may compensate for the loss of eNOS-derived NO in controlling blood pressure. Figure 6A shows that in aorta and circulating leukocytes, iNOS mRNA is significantly elevated 24 hours after Cl2 exposure, with no changes in nNOS expression in the aorta. iNOS protein expression in the aorta was localized in the endothelial layer and outer medial layers of the vessel wall (Figures 6B and 6C). To test if increased systemic iNOS plays a role in hemodynamics, rats were exposed to air or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). MAP was measured 24 hours thereafter, and then saline or the iNOS-specific inhibitor 1400W was administered. MAP was again measured 18 to 24 hours after 1400W addition (i.e., 42–48 h after Cl2 exposure). Figure 6D shows the significant increase in MAP after 1400W addition to Cl2–exposed animals compared with saline or 1400W addition to air-exposed rats. To evaluate if iNOS in the aorta contributed to vasomotor tone, the effects of 1400W on isolated aorta responses to PE and Ach were determined and compared with the effects of a general NOS inhibitor, L-NMMA. Figure 6E shows that L-NMMA potentiated PE-dependent constriction of aorta isolated from control and Cl2–exposed rats, whereas 1400W had no effect. Similarly, Figure 6F shows that L-NMMA inhibited Ach-induced vasodilation in all groups, whereas 1400W had no effect relative to respective controls.

Figure 5.

Effects of Cl2 on blood pressure. Rats were acclimatized to tail-cuff blood pressure measurement protocols and then exposed to air (open squares) or Cl2 (closed squares; 400 ppm, 30 min), and blood pressure measured again at 24 and 48 hours thereafter. −48 h and −24 h indicate measurements during acclimatization and indicate stable blood pressures before Cl2 exposure. Time 0 indicates measurements (30–60 min before Cl2 exposure). No significant differences between mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) as a function of time in air or Cl2 groups (by one-way ANOVA) or between groups (by two-way repeated measures ANOVA) were observed. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 2–4).

Figure 6.

Role of systemic inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induction in post-Cl2–induced changes in MAP. (A) Rats were exposed to air or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min), and 24 hours thereafter neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) or iNOS mRNA expression from aorta or circulating leukocytes was determined. mRNA levels are expressed relative to air controls and after normalization to GAPDH. Right-hand y axis is for leukocyte mRNA levels. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 2–3). *P < 0.001 by t test relative to respective air control. (B and C) Representative immunofluoresence images of iNOS (red) staining in aorta from control or 24 hours after Cl2 exposure, respectively. (D) Rats were exposed to air or Cl2 (400 ppm, 30 min). MAP was measured 24 hours thereafter, and saline or 1400W (10 mg/kg) was added by intraperitoneal injection. After a further 18 to 24 hours, MAP was measured. Data show changes in MAP (post 1400W – pre 1400W administration) and are mean ± SEM (n = 2–4). *P < 0.05 relative to air + 1400W or chlorine + saline by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test. (E and F) Effects of 1400W (10 μM) or L-NMMA (100 μM) on PE-induced vasoconstriction or Ach-induced vasodilation of aorta isolated from control of Cl2–exposed rats, respectively. Data show mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05 for control versus control + L-NMMA or Cl2 versus Cl2 + L-NMMA by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Role for TNF-α in Mediating Cl2–dependent Down-regulation of Aortic eNOS

TNF-α has been shown to down-regulate vascular eNOS expression and was proposed therefore as a potential mediator in transducing the effects of inhaled toxicants to the systemic vasculature (47). Therefore, TNF-α levels in the circulation were measured at 6 and 24 hours after Cl2 exposure and were below detection limits at both times (not shown). Moreover, no changes in the levels of IFN-γ or IL-1β were detected (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Cl2 toxicity is characterized by an initial injury to the lungs that progresses over days and months after cessation of the exposure leading to reactive airway dysfunction syndrome (15, 48). The focus of mechanisms for post-Cl2 exposure toxicity has been therefore on the pulmonary compartment, with the potential for Cl2 to cause injury to extrapulmonary vasculature receiving no attention. Underlying this premise is the general paradigm of environmental exposure to inhaled reactive oxidant gases being associated with acute and chronic cardiovascular inflammatory disease. We found that Cl2 promoted injury distal to the lung compartment that was characterized by postexposure decreases in expression and function of eNOS, which is similar to effects observed with other inhaled reactive oxidants, including ozone (18). An important distinction between Cl2 exposure and these other irritants is the exposure regimen. In the latter, exposures are intermittent, typically over longer time periods (days to weeks) and at relatively lower doses compared with Cl2, which is significantly shorter (min) in duration but occurs at higher doses, at least in industrial accident and military exposure situations. Data presented herein suggest that short-term (30 min) exposure to Cl2 (250–400 ppm) is sufficient to promote dysfunction in systemic eNOS over at least 48 hours after exposure. These results further support the model that dysfunction in the eNOS-signaling cascade is a common mechanism underlying how inhaled reactive oxidant species, independent of reactivity, promote systemic vascular toxicity.

Current therapeutics for Cl2–induced injury are symptomatic and focus on acute injury primarily associated with lung function. Our data suggest that systemic endothelial dysfunction should also be considered. Many studies have documented that a loss of eNOS signaling predisposes the vasculature to a hypertensive, proinflammatory, and procoagulant state, raising the question of whether Cl2 exposure has similar effects. Despite decreased eNOS, no changes in MAP were observed in rats after Cl2 exposure. eNOS-derived NO is one of many factors that work in balance to control vascular tone, and we reasoned therefore that concomitant decreased vasoconstrictor or increased vasodilator activity was also induced by Cl2. Administration of the iNOS-specific inhibitor 1400W increased MAP only in Cl2–exposed animals, suggesting that increased vasodilator activity from iNOS was countering decreased eNOS-derived NO to maintain blood pressure. Moreover, the lack of effect of 1400W on isolated vessels suggests that iNOS in circulating cells plays an important role in maintaining MAP in the background of eNOS inhibition. The mechanisms by which this could occur are not clear and require further study but could involve direct effects of NO derived from iNOS in circulating cells or iNOS-dependent changes in other vasodilators or vasoconstrictors. For example, iNOS can activate cycocloxygenase-2 (49), which in turn could alter the balance of prostanoid-derived vasodilator/vasoconstrictors. These data suggest that Cl2 exposure acutely alters the balance of vasoconstrictor and vasodilator mechanisms in the circulation and specifically those related to NO homeostasis. Moreover, given the relatively high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in humans, the potential for Cl2 to cause systemic hypertension and inflammation in these individuals where eNOS signaling is already compromised could be significant. Consistent with this notion, case reports of accidental Cl2 exposure document a prevalence of delayed hypertension after exposure (2), although earlier reports document no hypertension (50). We hypothesize that Cl2 exposure disrupts the regulatory mechanisms for controlling vascular homeostasis, which, on the background of existing vascular injury, may exacerbate endothelial dysfunction and may have implications for treatment of patients with existing cardiovascular problems. Also, the variance of underlying cardiovascular disease may contribute to the variance in hypertension observed in case studies of Cl2 exposure.

Our data support the model whereby Cl2 inhalation decreases expression of eNOS protein, which leads to a loss of agonist-induced vasodilation. There were no changes in α1-adrenergic receptor-dependent contraction or in NO-dependent vasodilation per se, suggesting that the loss of Ach-induced dilation was solely due to decreased expression of eNOS and less NO being formed in the vessel wall. This is further supported by decreased levels of plasma nitrite, a selective marker for vascular eNOS activity (51). Whether eNOS degradation is increasing or gene transcription/translation is decreasing is not clear. The finding that eNOS protein was decreased despite eNOS mRNA expression being increased suggests that increased protein turnover is occurring. Alternatively, increased eNOS mRNA may represent a compensatory response to decreased protein levels. Irrespective of the molecular mechanism, a key question remaining is how the effects of Cl2, the direct reactivity of which with biological molecules is limited to the epithelial lining fluid, are transduced to the periphery to mediate down-regulation of eNOS expression in the aorta. This question applies to other inhaled irritants, and one potential common mechanism that may encompass inhaled irritants with different reactivities involves stimulation of inflammation secondary to the initial exposure (21). In this model, initial injury in the lungs activates alveolar macrophages and other inflammatory cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines that recruit other immune cells to the lung (e.g., neutrophils) and in doing so encompass the so-called “second wave” of inflammation. The possibility remains therefore that increased proinflammatory cytokines in the pulmonary compartment may cross over into the circulation, which in turn may affect systemic endothelial function. Similar principles have been proposed to explain the development of multiorgan failure in patients with primary adult respiratory distress syndrome. One candidate includes TNF-α, which down-regulates eNOS expression in endothelial cell culture and in vivo models (47, 52). However, no changes in circulating TNF-α or other proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ or IL-1β) were observed. At first glance, this would suggest that Cl2 does not promote vascular inflammation. However, Cl2 did increase iNOS expression in circulating leukocytes and vascular tissue. iNOS is an inducible enzyme that is associated with inflammation, and previous studies have shown Cl2–dependent increases in iNOS in the lung, consistent with proinflammatory effects in this compartment (13). Moreover, no changes in nNOS mRNA suggest specificity toward increases in the iNOS isoform. Using iNOS as an inflammatory marker, our data suggest that vascular inflammation occurs after Cl2 exposure, albeit without detectable changes in proinflammatory cytokines. We have not measured all cytokines that could contribute to iNOS up-regulation and acknowledge that rapid turnover of cytokines in the circulation, together with the possibility that only small changes in cytokine concentrations may be required to mediate down-regulation of eNOS and up-regulation of iNOS, may have precluded our ability to detect significant changes. Further studies are required to test this hypothesis.

The concept of Cl2–derived products in modulating eNOS and vascular function is supported by studies that have established the connection between endogenously derived reactive chlorine species (e.g., hypochlorous acid and chloramines) and the development of cardiovascular disease. Specifically, chlorination of biological molecules (lipids, l-arginine) by myeloperoxidase-derived HOCl form products that inhibit eNOS, and recently HOCl-derived advanced glycation end products have been shown to inhibit eNOS expression (28, 29, 32–36, 53, 54). Moreover, advanced glycation end products are activators of iNOS (55), further supporting these species as candidates for transducing extrapulmonary effects of post-Cl2 exposure. Whether there is an overlap in mechanisms causing vascular eNOS dysfunction by exogenous Cl2 exposure and endogenously formed reactive chlorine species remains to be determined.

In summary, this study shows that Cl2 can lead to postexposure extrapulmonary vascular endothelial dysfunction and inflammation characterized by the loss of eNOS-derived signaling and increased iNOS expression. We hypothesize that this disrupts the normal balance of vascular NO homeostasis, which may lead to acute and chronic cardiovascular events that we propose should be considered when providing medical care for victims of Cl2 exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P30DK56336 NIDDK Metabolism Core Laboratory for the Nutrition Obesity Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham for assistance with cytokine measurements and Dr. C. Roger White for assistance with vessel studies.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant U01ES015676 (S.M.), HD59142 (AM), and by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant U54ES017218).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0151OC on December 3, 2010

Author Disclosure: R.P.P. has received support for travel to meetings for the study and payment for writing the manuscript from the NIH/University of Alabama at Birmingham. E.P. has received payment for lectures from academic institutions. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Evans RB. Chlorine: state of the art. Lung 2005;183:151–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Sickle D, Wenck MA, Belflower A, Drociuk D, Ferdinands J, Holguin F, Svendsen E, Bretous L, Jankelevich S, Gibson JJ, et al. Acute health effects after exposure to chlorine gas released after a train derailment. Am J Emerg Med 2009;27:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenck MA, Van Sickle D, Drociuk D, Belflower A, Youngblood C, Whisnant MD, Taylor R, Rudnick V, Gibson JJ. Rapid assessment of exposure to chlorine released from a train derailment and resulting health impact. Public Health Rep 2007;122:784–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almagro Nievas D, Acuna Castillo R, Hernandez Jerez A, Robles Montes A. Investigation of an outbreak of acute respiratory illness due to exposure to chlorine gas in a public swimming pool [in Spanish]. Gac Sanit 2008;22:287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cevik Y, Onay M, Akmaz I, Sezigen S. Mass casualties from acute inhalation of chlorine gas. South Med J 2009;102:1209–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szinicz L. History of chemical and biological warfare agents. Toxicology 2005;214:167–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matalon S, Maull EA. Understanding and treating chlorine-induced lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crouch EC, Hirche TO, Shao B, Boxio R, Wartelle J, Benabid R, McDonald B, Heinecke J, Matalon S, Belaaouaj A. Myeloperoxidase-dependent inactivation of surfactant protein d in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 2010;285:16757–16770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leustik M, Doran S, Bracher A, Williams S, Squadrito GL, Schoeb TR, Postlethwait E, Matalon S. Mitigation of chlorine-induced lung injury by low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L733–L743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song W, Wei S, Zhou Y, Lazrak A, Liu G, Londino JD, Squadrito GL, Matalon S. Inhibition of lung fluid clearance and epithelial Na+ channels by chlorine, hypochlorous acid, and chloramines. J Biol Chem 2010;285:9716–9728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly SC, FitzGerald MX. Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (RADS) due to chlorine gas exposure. Ir J Med Sci 1990;159:275–276, discussion 276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunnarsson M, Walther SM, Seidal T, Bloom GD, Lennquist S. Exposure to chlorine gas: effects on pulmonary function and morphology in anaesthetised and mechanically ventilated pigs. J Appl Toxicol 1998;18:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JG, Campbell HR, Iijima H, Gautrin D, Malo JL, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q, Maghni K. Chlorine-induced injury to the airways in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian X, Tao H, Brisolara J, Chen J, Rando RJ, Hoyle GW. Acute lung injury induced by chlorine inhalation in c57bl/6 and fvb/n mice. Inhal Toxicol 2008;20:783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuck SA, Ramos-Barbon D, Campbell H, McGovern T, Karmouty-Quintana H, Martin JG. Time course of airway remodelling after an acute chlorine gas exposure in mice. Respir Res 2008;9:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uyan ZS, Carraro S, Piacentini G, Baraldi E. Swimming pool, respiratory health, and childhood asthma: should we change our beliefs? Pediatr Pulmonol 2009;44:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song W, Wei S, Liu G, Yu Z, Estell K, Yadav A, Schwiebert L, Matalon S. Post exposure administration of a b2-agonist decreased chlorine induced airway hyperreactivity in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Chuang GC, Yang Z, Westbrook DG, Pompilius M, Ballinger CA, White CR, Krzywanski DM, Postlethwait EM, Ballinger SW. Pulmonary ozone exposure induces vascular dysfunction, mitochondrial damage, and atherogenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L209–L216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo X, Oldham MJ, Kleinman MT, Phalen RF, Kassab GS. Effect of cigarette smoking on nitric oxide, structural, and mechanical properties of mouse arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;291:H2354–H2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knuckles TL, Lund AK, Lucas SN, Campen MJ. Diesel exhaust exposure enhances venoconstriction via uncoupling of enos. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2008;230:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills NL, Donaldson K, Hadoke PW, Boon NA, MacNee W, Cassee FR, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A, Newby DE. Adverse cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2009;6:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncada S. Nitric oxide: discovery and impact on clinical medicine. J R Soc Med 1999;92:164–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Napoli C, Ignarro LJ. Nitric oxide and pathogenic mechanisms involved in the development of vascular diseases. Arch Pharm Res 2009;32:1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Qaisi M, Kharbanda RK, Mittal TK, Donald AE. Measurement of endothelial function and its clinical utility for cardiovascular risk. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008;4:647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Vita JA. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1149–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squadrito GL, Postlethwait EM, Matalon S. Elucidating mechanisms of chlorine toxicity: reaction kinetics, thermodynamics, and physiological implications. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010;299:L289–L300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergt C, Pennathur S, Fu X, Byun J, O'Brien K, McDonald TO, Singh P, Anantharamaiah GM, Chait A, Brunzell J, et al. The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes hdl in the human artery wall and impairs abca1-dependent cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:13032–13037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsche G, Heller R, Fauler G, Kovacevic A, Nuszkowski A, Graier W, Sattler W, Malle E. 2-chlorohexadecanal derived from hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein-associated plasmalogen is a natural inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide biosynthesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:2302–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marsche G, Semlitsch M, Hammer A, Frank S, Weigle B, Demling N, Schmidt K, Windischhofer W, Waeg G, Sattler W, et al. Hypochlorite-modified albumin colocalizes with RAGE in the artery wall and promotes MCP-1 expression via the RAGE-Erk1/2 MAP-kinase pathway. FASEB J 2007;21:1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCall MR, Carr AC, Forte TM, Frei B. LDL modified by hypochlorous acid is a potent inhibitor of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:1040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMillen TS, Heinecke JW, LeBoeuf RC. Expression of human myeloperoxidase by macrophages promotes atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation 2005;111:2798–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stocker R, Huang A, Jeranian E, Hou JY, Wu TT, Thomas SR, Keaney JF Jr. Hypochlorous acid impairs endothelium-derived nitric oxide bioactivity through a superoxide-dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:2028–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Xie Z, Reece R, Pimental D, Zou MH. Uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxidase synthase by hypochlorous acid: role of NAD(P)H oxidase-derived superoxide and peroxynitrite. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:2688–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Cheng Y, Ji R, Zhang C. Novel model of inflammatory neointima formation reveals a potential role of myeloperoxidase in neointimal hyperplasia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;291:H3087–H3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang C, Patel R, Eiserich JP, Zhou F, Kelpke S, Ma W, Parks DA, Darley-Usmar V, White CR. Endothelial dysfunction is induced by proinflammatory oxidant hypochlorous acid. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;281:H1469–H1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C, Reiter C, Eiserich JP, Boersma B, Parks DA, Beckman JS, Barnes S, Kirk M, Baldus S, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. L-arginine chlorination products inhibit endothelial nitric oxide production. J Biol Chem 2001;276:27159–27165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng L, Nukuna B, Brennan ML, Sun M, Goormastic M, Settle M, Schmitt D, Fu X, Thomson L, Fox PL, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I is a selective target for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation and functional impairment in subjects with cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 2004;114:529–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng L, Settle M, Brubaker G, Schmitt D, Hazen SL, Smith JD, Kinter M. Localization of nitration and chlorination sites on apolipoprotein A-I catalyzed by myeloperoxidase in human atheroma and associated oxidative impairment in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J Biol Chem 2005;280:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bell DP. Management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) following chlorine exposure [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;176:A314. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svendsen ER, Whittle NC, Sanders L, McKeown RE, Sprayberry K, Heim M, Caldwell R, Gibson JJ, Vena JE. Grace: public health recovery methods following an environmental disaster. Arch Environ Occup Health 2010;65:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav AK, Bracher A, Doran SF, Leustik M, Squadrito GL, Postlethwait EM, Matalon S. Mechanisms and modification of chlorine-induced lung injury in animals. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010;7:278–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vitturi DA, Teng X, Toledo JC, Matalon S, Lancaster JR Jr, Patel RP. Regulation of nitrite transport in red blood cells by hemoglobin oxygen fractional saturation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;296:H1398–H1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaik SS, Soltau TD, Chaturvedi G, Totapally B, Hagood JS, Andrews WW, Athar M, Voitenok NN, Killingsworth CR, Patel RP, et al. Low intensity shear stress increases endothelial elr+ cxc chemokine production via a focal adhesion kinase-p38{beta} MAPK-NF-{kappa}B pathway. J Biol Chem 2009;284:5945–5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Donnell VB, Freeman BA. Interactions between nitric oxide and lipid oxidation pathways: implications for vascular disease. Circ Res 2001;88:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel RP, McAndrew J, Sellak H, White CR, Jo H, Freeman BA, Darley-Usmar VM. Biological aspects of reactive nitrogen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999;1411:385–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White CR, Darley-Usmar V, Berrington WR, McAdams M, Gore JZ, Thompson JA, Parks DA, Tarpey MM, Freeman BA. Circulating plasma xanthine oxidase contributes to vascular dysfunction in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:8745–8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson HD, Rahmutula D, Gardner DG. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits endothelial nitric-oxide synthase gene promoter activity in bovine aortic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demnati R, Fraser R, Martin JG, Plaa G, Malo JL. Effects of dexamethasone on functional and pathological changes in rat bronchi caused by high acute exposure to chlorine. Toxicol Sci 1998;45:242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim SF, Huri DA, Snyder SH. Inducible nitric oxide synthase binds, S-nitrosylates, and activates cyclooxygenase-2. Science 2005;310:1966–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beach FX, Jones ES, Scarrow GD. Respiratory effects of chlorine gas. Br J Ind Med 1969;26:231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, Scheeren T, Godecke A, Schrader J, Schulz R, et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med 2003;35:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao X, Xu X, Belmadani S, Park Y, Tang Z, Feldman AM, Chilian WM, Zhang C. TNF-alpha contributes to endothelial dysfunction by upregulating arginase in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thukkani AK, McHowat J, Hsu FF, Brennan ML, Hazen SL, Ford DA. Identification of alpha-chloro fatty aldehydes and unsaturated lysophosphatidylcholine molecular species in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation 2003;108:3128–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soro-Paavonen A, Zhang WZ, Venardos K, Coughlan MT, Harris E, Tong DC, Brasacchio D, Paavonen K, Chin-Dusting J, Cooper ME, et al. Advanced glycation end-products induce vascular dysfunction via resistance to nitric oxide and suppression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Hypertens 2010;28:780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang PC, Chen TH, Chang CJ, Hou CC, Chan P, Lee HM. Advanced glycosylation end products induce inducible nitric oxide synthase (INOS) expression via a p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. Kidney Int 2004;65:1664–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.