Abstract

Diketopiperazines (DKPs) are a well-known class of heterocycles that have emerged as a promising biologically active scaffold. Solid-phase organic synthesis has become an important tool in the combinatorial exploration of these privileged structures, expediting the synthesis and, often, the discovery of active compounds. We recently identified several DKPs that are capable of inhibiting the luminescence response of the bacterial symbiont Vibrio fischeri, and we sought to further test the scope of this biological activity. Herein, we report the synthesis of DKP macroarrays using a SPOT-synthesis approach based on an Ugi/DeBoc/Cyclize strategy. Neither a spacer nor a linker was required for macroarray construction on cellulose support, and the cyclative cleavage produced high purity DKPs in good yields. Using this protocol, we prepared a library of 400 DKPs on cellulose support and evaluated its members as luminescence inhibitors in V. fischeri. We found six DKPs capable of inhibiting luminescence by greater than 80% at 500 μM. Collectively, this work serves to further highlight the utility of the small molecule macroarray platform for the synthesis and evaluation of focused libraries.

Keywords: Diketopiperazine, Luminescence, Small molecule macroarray, Spatially addressed solid-phase synthesis, SPOT-synthesis, Ugi four-component reaction, Vibrio fischeri

Introduction

The development of general methods for the synthesis of small molecule libraries is a major goal of the combinatorial chemistry and chemical biology research communities. To address this challenge, we have developed an efficient method for library generation that is based on small molecule macroarrays.1-7 Cellulose macroarrays have the potential to address several of the drawbacks of traditional combinatorial synthesis platforms (i.e., solid-phase beads) – these arrays are straightforward to manipulate, remarkably robust, inexpensive, and amenable to numerous screening applications where the array compounds are either bound to or cleaved from the planar support. In addition to exploring the scope and limitations of synthetic methodologies on planar cellulose, our laboratory has also developed novel methods for on-support compound screening, including macroarray transfer and agar overlay techniques.7 These methods have dramatically accelerated the discovery of chemical probes for various biological targets.

The chances of finding a “hit” in a small molecule library, however, whether constructed via a macroarray approach or any other, are still low. One strategy to improve the efficiency of combinatorial chemistry and subsequent biological screening is to identify and utilize “privileged structures” in library design – that is, select small molecule scaffolds that bind to a variety of receptor classes with high affinities.8 Cyclic dipeptides, or 2,5-diketopiperazines (DKPs), have proven to be one such scaffold.9,10 Recent advances in solid-phase combinatorial DKP synthesis, including secondary acylation and N-alkylation strategies and multiple component reactions (MCRs), have provided the tools needed for the rapid synthesis of DKPs.11, 12 For example, we recently reported a water-assisted Ugi 4CR for the solid-phase synthesis of DKPs that made use of Armstrong’s convertible isonitrile and a photocleavable linkage strategy (Figure 1, route A).6

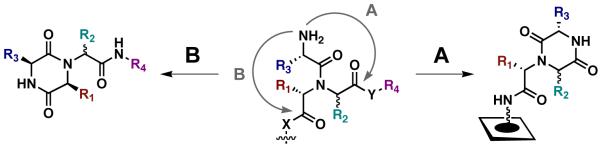

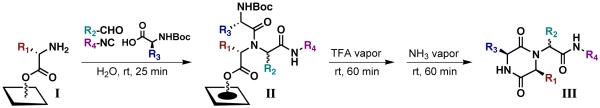

Figure 1.

Two routes to DKPs via an Ugi 4CR on planar cellulose support. Route A utilizes an N-Fmoc-protected amino acid, and cyclization occurs during deprotection as we have previously reported6 (X=NH-support, Y=O, R4=Me); Route B (UDC) requires an N-Boc-protected amino acid, and cleavage from the support occurs during DKP cyclization, yielding only pure product (X=O, Y=NH, R4=diversity point).

Analysis of past work in the area reveals that one of the most amenable routes to the combinatorial synthesis of DKPs is the cyclization and concomitant cleavage (or “cyclative cleavage”) of dipeptide derivatives from solid support.11, 12 These strategies yield DKPs in high purities, as the cleavage releases only the cyclic products. One such solid-phase strategy utilizes the Ugi 4CR to simultaneously introduce three additional points of diversity onto support-bound amines. This MCR route allows for a cyclative cleavage when N-Boc-protected amino acid components are used and is termed the “Ugi/De-Boc/Cyclize” (UDC) method.13 This versatile chemistry has been used to develop a range of lead DKPs with a variety of biological activities.14,15,16 In the current study, we sought to explore the feasibility of the UDC method for DKP synthesis on our small molecule macroarray platform (Figure 1, route B). We found that (1) this method was compatible with planar cellulose support, and (2) the cyclative cleavage greatly streamlined DKP synthesis, as installation of neither a spacer nor a linker was required.

In addition to evaluating an UDC route to DKP synthesis, we also sought to explore the biological activity of the resulting DKP macroarrays. DKPs have attracted considerable recent attention, as they have been reported to both activate and inhibit quorum sensing (QS) behaviors in certain Gram-negative bacteria.17,18 QS plays a prevalent role in bacterial infection, and has emerged as an extremely active area of research in the drug discovery, chemical biology, and microbiology communities.19 We recently performed an in-depth study of the structural requirements of DKPs on their reported QS modulatory activity.20 Interestingly, we found that DKPs do not interact directly with QS receptors (LuxR-type), as originally assumed. We discovered, however, that cyclo(l-Pro-l-p-I-Phe) and cyclo(l-Pro-l-p-Cl-Phe) could inhibit the luminescent response of the bacterial symbiont Vibrio fischeri (Δ–luxI)21,22 to its native QS signal, N-(3-oxo)-octanoyl L-homoserine lactone (OHHL).20 Herein, we tested whether more complex DKPs, synthesized in macroarray format, could likewise inhibit this QS-regulated behavior. The macroarray platform was found to be fully compatible with solution-phase bacteriological assays, and several DKPs with activities comparable to our initial lead structures were identified. Such ligands should prove useful as probes to further explore the mechanisms of DKP-mediated luminescence modulation in V. fischeri.

Results and Discussion

General Synthetic Design

The UDC strategy requires attachment of library members to the support through an ester bond to allow for cyclative cleavage of the DKP products. Therefore, we envisioned attaching amino acids directly to the native hydroxyl groups of the cellulose support via a “blanket” esterification reaction (i.e., functionalization of the entire support surface) to generate amino-functionalized support I (Scheme 1). By using N-Fmoc α-amino acids, the loadings of these initial building blocks could be easily obtained through UV quantitation methods.23 Following N-Fmoc deprotection, support I would be subjected to our water-assisted Ugi 4CR conditions3,6 (utilizing N-Boc α-amino acids) to produce Ugi product arrays II. Thereafter, we sought to perform N-Boc deprotection using TFA vapor to avoid washing steps and prepare the support for cyclization. “Dry” cyclization conditions using only ammonia vapor24 would then produce a spatially addressed, cleaved DKP array (III) ready for biological assays. Using these two vapor-phase methods, we anticipated that no solvents would be used once the Ugi arrays (II) were generated. In addition, unlike previously reported syntheses,5 no heating would be required for macroarray construction, which would further simplify the synthesis of the DKP arrays (III).

Scheme 1.

Our general UDC strategy on ester-bound amine-functionalized cellulose support.

Library Design

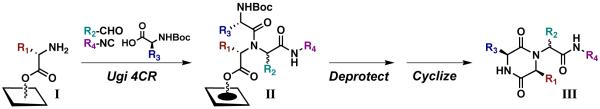

We sought to generate a sizeable DKP library on amino supports I in order to test our synthetic methods. The aldehyde and isocyanide building blocks shown in Figure 2 had given high yields and purities in our previously reported Ugi 4CRs on planar support, and thus these were included in the current library synthesis.3,6 The five α-amino acid building blocks were chosen to explore in part the effects of increasing steric bulk on DKP formation (Gly, Ala, Leu, Phe, and p-Cl-Phe (Cph)). l-Val and l-Ile were not included as α-amino acid building blocks, as steric bulk at the β-position has been shown to hinder DKP cyclization.12 We sought to test whether the positioning of the DKP side chain affected biological activity, and therefore the N-Fmoc α-amino acids used to generate support I matched the N-Boc α-amino acid building blocks used in the Ugi 4CR (to generate support II). As introduced above, we previously found that DKPs derived from Cph showed inhibitory activity in luminescence assays, and therefore this building block was included in our library.20 Early synthetic studies indicated that p-I-Phe did not give sufficiently high DKP yields or purities, however, and this building block was excluded from our final DKP library.

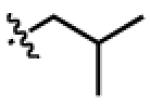

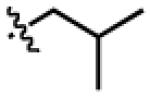

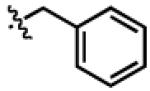

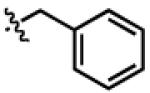

Figure 2.

Building blocks used in the Ugi 4CR to generate macroarrays of DKPs (III); a: Gly, b: Ala, c: Leu, d: Phe, e: 4-Cl-Phe or Cph.

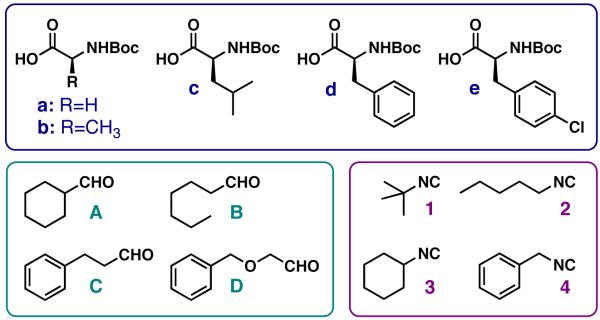

Amino Cellulose Functionalization

Our synthesis of DKP macroarrays commenced with the construction of amino-derived cellulose support I (Scheme 2). Dots were marked on a 10 × 10 cm sheet of Whatman filter paper at distances 0.9 cm apart using a pencil. In this format, 80 compound spots (area/spot = 0.3 cm2) could be accommodated on a single sheet without any detectable cross contamination (see Figure S-1 for macroarray layout). Squares of marked filter paper were subjected to blanket esterification with five N-Fmoc α-amino acids (Gly, Ala, Leu, Phe, and Cph; side chains shown in Figure 2) using a room temperature protocol adapted from Frank to generate five subarrays.25 By adjusting the reagent concentrations of the individual reactions, amino acid loadings of ~500 nmol/cm2 were achieved (as determined by UV Fmoc quantitation; see Supp. Info. for details).23 These reactions were found to be sensitive to ambient humidity, but performing the esterification in a nitrogen-filled glove bag gave reproducible loadings. N-Fmoc deprotection of the five amino acid-derivatized subarrays with 4% DBU in DMF yielded support I, and set the stage for the Ugi 4CRs in SPOT-synthesis format.

Scheme 2.

Construction of amino acid-derivatized support I via blanket esterification. DIC = N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide; NMI = N-methyl imidazole; DBU = 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene; DMF = N,N’-dimethylformamide.

DKP macroarray construction

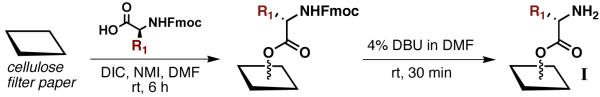

The Ugi 4CRs were performed on amino supports I using our previously reported procedure (Scheme 3).3,6 In brief, solutions of N-Boc α-amino acids (Boc-AA-OH, a–e; Figure 2) were prepared in DMF. Aliquots of each solution were mixed in a 4:1 (v/v) ratio with the corresponding neat aldehyde (A–D; Figure 2) to generate 20 unique Boc-AA-OH/RCHO mixtures. A multi-channel pipette was then used to deliver both the water and the Boc-AA-OH/RCHO mixtures onto supports I in order to expedite the synthesis (see Exp. Section for details). Thereafter, small volumes of isocyanide (1–4; Figure 2) were spotted individually on top of the other reagents. These spatially-addressed reactions were allowed to proceed at room temperature for 25 min, after which time the supports were washed and dried to yield twenty 20-member Ugi macroarrays (II). We found that the macroarrays were stable for longer than a week when stored on the bench-top at this point in the synthesis. N-Boc deprotection was performed on dry, intact macroarrays (II) in a TFA-containing vacuum desiccator.2 Next, several bases were tested for the DKP cyclization-cleavage step, including tert-butyl amine, Et3N, and piperidine; however, treatment with volatile NH3 gave the highest yield of DKP product (as determined by HPLC integration). Therefore, cyclization reactions were performed on the N-Boc deprotected macroarrays inside an NH3-filled Pyrex dish (see Supp. Info. for details) to generate the DKP products (III) as spatially addressed, non-covalently bound arrays. DKP products were named according to the order of their side chains (as shown in Figure 2). The library members are designated according their initial ester-linked amino acids (R1: Gly, Ala, Leu, Phe, or Cph), their aldehyde building blocks (R2: A–D) their acid components (R3: a–e), and their isocyanide side chains (R4: 1–4).

Scheme 3.

Construction of DKPs III from amino acid-derivatized support I via Ugi 4CRs, acid mediated deprotection, and base mediated cyclative cleavage.

Compound Purities

To obtain DKP purity data, 34 randomly chosen Ugi 4CR products (II) were punched out of the array into individual vials, and subjected to TFA vapor deprotection and NH3 cyclization. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses of this subset of DKPs III (8.5%) cleaved from the macroarrays indicated good to excellent purities (81–99%; Table 1). We were pleased to observe that all of these test library members were greater than 80% pure, with an average purity of 93%. A careful analysis of the DKP purities produced by the individual building blocks did not show any significant trends (i.e., all of the building blocks gave approximately the same purities; See Table S-3).

Table 1.

Purity data for representative DKP macroarray members III

| DKP | purity (%)a |

DKP | purity (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlyAb1 | 82 | LeuBb4 | 90 |

| GlyAc1 | 97 | LeuCa1 | 81 |

| GlyAd1 | 92 | LeuCd1 | 81 |

| GlyBe2 | 84 | LeuDe2 | 95 |

| GlyCb3 | 99 | PheAb4 | 91 |

| GlyCd1 | 97 | PheBb3 | 96 |

| AlaAc2 | 89 | PheBe1 | 97 |

| AlaAd3 | 94 | PheCa1 | 93 |

| AlaBa3 | 91 | PheCc2 | 97 |

| AlaBd1 | 82 | PheDa3 | 98 |

| AlaCd2 | 98 | PheDd3 | 98 |

| AlaCe4 | 93 | CphAa1 | 97 |

| AlaDd1 | 99 | CphBb2 | 90 |

| LeuAb1 | 96 | CphCb3 | 97 |

| LeuAd2 | 94 | CphCd1 | 94 |

| LeuAd3 | 96 | CphCd3 | 98 |

| LeuBa2 | 94 | CphDc4 | 95 |

Determined by integration of LC traces (UV detection at 218 nm).

DKP Product Yields

In previous studies, we have incorporated chemical linkers into our macroarray syntheses, and product yields have been calculated by determining the ratio of cleaved starting material to product.2-7 In the current research, however, this approach was not feasible, as the DKP products (III) were released from the macroarray through a cyclative-cleavage reaction and no starting material was released from the planar support. Therefore, we used calibration curves to quantify our DKP product (III) yields (generated via LC with UV detection). Assuming that aromatic rings would affect the absorbance of the compounds more significantly than aliphatic side chains, we selected four DKPs containing 0–3 aromatic (Ar) moieties (0 Ar: GlyAb1, 1 Ar: GlyAd1, 2 Ar: GlyCd1, 3 Ar: CphCd1) as model compounds. We note that only eight of the 400 DKPs (2%) contained four aromatic rings, and thus we excluded this substructure from our yield analysis. The four model DKPs were synthesized on planar support I with higher loadings of the initial amino acid building block (up to 1000 nmol/cm2) than that used for macroarray synthesis. The Ugi arrays (II) were synthesized by spotting sufficient reagents to entirely cover a 5 × 10 cm amino support (I). Deprotection and cyclization steps were performed on the intact sheets, after which the model DKPs were eluted from the supports and purified by semi-preparative HPLC. LC-MS calibration curves were generated for each model DKP at 218 nm (as all of the compounds contained three amide bonds), and yields were calculated for the DKPs generated in the 400-member macroarray.

We found that the all-aliphatic model DKP (GlyAb1) gave 95% yield, 1 Ar (GlyAd1) gave 89% yield, 2 Ar (GlyCd1) gave 78% yield, and 3 Ar (CphCd1; which contains two aromatic rings on one face of its DKP core and would be expected to have somewhat hindered cyclization) gave 75% yield. These values were independently validated by UV Fmoc quantitation of the unreacted amine building block/uncyclized product (1Ar: 94–98%; 2Ar: 82–94%; 3Ar: 91–97%; 3Ar: 64–88%). We did not observe any stereo induction during the Ugi 4CR as we have previously, which supports our previous finding that linkers can affect the diastereomeric ratio of Ugi 4CR products.3 The diastereomers that could be resolved by LC were produced in a 1:1 ratio, which allowed for equal concentrations of each isomer to be tested in our bioassay (see below).

We sought to apply our model calibration curves to qualitatively analyze the yields of all of the DKP macroarray members (III). However, this approach proved to be ineffectual, as each DKP product absorbed light differently at 218 nm (e.g., in some cases yields >100% were calculated using the model DKP calibration curves; data not shown). We therefore analyzed the yields of DKPs III through quantitation of the unreacted amine building blocks/uncyclized Ugi products. The Ala subarray members were selected for this analysis, as they appeared to give the lowest yields by LC integration. UV Fmoc quantitation of these spots revealed residual amine loadings of 12–20%, indicating that the DKP yields on the Ala subarray were 80–98%. Based on these data, we were confident that the DKP macroarray would yield ~400–500 μM final product concentrations (per spot) in our bioassay format. Consequently, we deemed the macroarray yields acceptable to proceed to biological assays (see below).

Biological Evaluation of DKP Macroarray

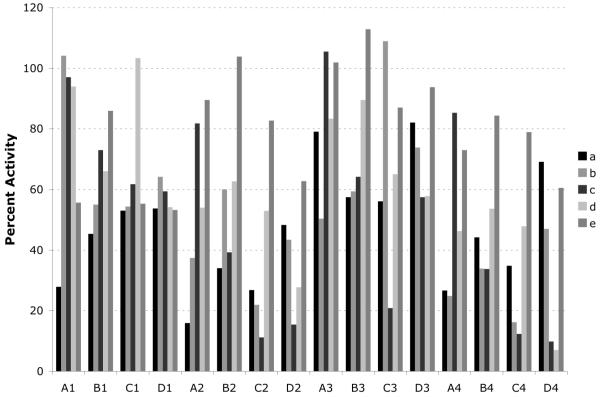

Testing the abilities of the DKPs (III) to inhibit luminescence in V. fischeri required a solution-phase cell-based assay. For previous solution-phase assays of macroarray members, cleaved spots were punched out into individual vials, compounds were eluted with solvent, the solvent was removed, DMSO was added to generate stock solutions, and aliquots of these solutions were pipetted into 96-well plates.7 This process was cumbersome, and in the current work we sought to simplify the solution-phase screening process. We found that cleaved macroarray members could be punched directly into the wells of a 96-well plate, and subjected to bacteriological screens in the presence of the paper disks (see Figure S-2). Aliquots of V. fischeri (Δ–luxI)21 containing 5 μM OHHL (EC50 value in this strain) were added to the plates, and DKPs were tested for luminescence antagonistic activity. Following room temperature incubation, bacterial cells were transferred away from the paper disks into white-walled multititer plates, and the optical density and luminescence of each well were measured on a plate reader (see Figure 3 for representative data). We identified a number of moderate inhibitors (>80% inhibition at 500 μM) from this primary screen, and moved forward with the best hit(s) from four of the amino acid subarrays (Gly, Leu, Phe, and Cph) for on-support assay validation (see Table 2; GlyCc2, GlyDc4, GlyDd4, LeuCa2, LeuDa4, PheDa4, and CphDa1).

Figure 3.

Antagonism assay data generated from the Gly-based subarray in V. fischeri (Δ–luxI). DKPs were tested at ~550 μM vs. 5 μM OHHL (EC50 value). Array members are grouped according to aldehyde (A–D) and isocyanide (1–4) components. The individual bars in each group show the effect of the second amino acid side chain (a–e) on the activity of the DKP. Letter and number designations for library building blocks are given in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Luminescence inhibition by DKPs in V. fischeri a

| DKP | macroarray members (% inhibition)b |

authentic samples (% inhibition)c |

|---|---|---|

| GlyCc2 | 89 | 91 |

| LeuCa2 | 86 | 80 |

| GlyDc4 | 90 | 96 |

| LeuDa4 | 95 | 79 |

| GlyDd4 | 95 | -- d |

| PheDa4 | 95 | 89 |

| CphDa1 | 89 | 57 |

| GlyAb1 e | -- f | 45 |

| GlyAd1 Ae,g | -- f | 68 |

| GlyAd1 Be,g | -- f | 68 |

| GlyCd1 | -- f | 37 |

Tested against the EC50 of natural ligand (5 μM OHHL).

Tested at approximately 550 μM (510 nmol/cm2 × 0.283 cm2 / 255 μL).

Tested at 500 μM.

Sample tested in dose response format: IC50 = 160 μM.

Calibration curve standards included as inactive controls.

Tested for yield, not subjected to macroarray biological screen.

Diastereomers separated by HPLC; see Supp. Info. for 1H NMR data.

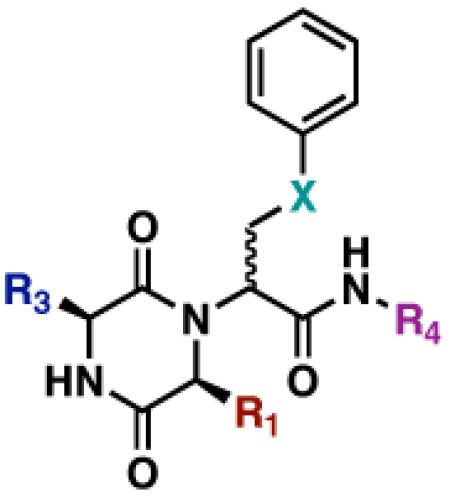

To verify our on-support assay results, we performed luminescence antagonism assays using stock solutions of authentic samples of the DKP hits. To do so, we scaled-up the synthesis of our seven desired DKPs by spotting enough Ugi 4CR reagents onto the appropriately functionalized amino support I to entirely cover the 5 × 10 cm sheet. Deprotection and DKP cyclization were carried out as described for macroarray synthesis above. HPLC purification of the products gave 1–5 mg of the pure DKPs. Stock solutions of these authentic samples were made in DMSO, and the inhibitory activities were measured at 500 μM against 5 μM OHHL in V. fischeri (Δ–luxI). We included our model DKPs (see above) in this screen as inactive controls. Table 2 shows that our primary antagonism assay of the macroarray was indeed able to uncover true luminescence inhibitors, as the antagonism data obtained from the macroarray samples and the authentic samples compared favorably with one another. DKPs derived from aromatic aldehydes gave the greatest antagonistic activities (Table 3). Interestingly, the positioning of the amino acid side chains appeared to be unimportant – that is, the most active DKPs from each subarray were isomers of each other (with the amino acid side chains switched; Table 3). Additionally, we were surprised to see that the diastereomers of GlyAd1 (that were separated by HPLC) displayed the same inhibitory activities, suggesting that the stereochemistry at the aldehyde position is not important for DKP activity. Inhibitory dose response analysis of our most active DKP (GlyDd4) gave an IC50 of 160 μM, comparable to the most active “simple” cyclic dipeptide, cyclo(l-Pro-l-p-I-Phe), which we identified in our earlier study (116 μM).20

Table 3.

Structures of active DKPs uncovered in the V. fischeri luminescence inhibition assay

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKP | R1 | R3 | R4 | X |

| GlyCc2 | H |

|

n-C5H11 | CH2 |

| LeuCa2 |

|

H | n-C5H11 | CH2 |

| GlyDc4 | H |

|

CH2Ph | OCH2 |

| LeuDa4 |

|

H | CH2Ph | OCH2 |

| GlyDd4 | H |

|

CH2Ph | OCH2 |

| PheDa4 |

|

H | CH2Ph | OCH2 |

Summary

The DKP scaffold is a proven privileged structure for the design of small molecule libraries. Herein, we have demonstrated the compatibility of the small molecule macroarray platform with DKP library synthesis. We developed an expedient, UDC synthetic route to DKPs that did not require the installation of a linker or a spacer on the planar cellulose support. The use of water-assisted Ugi 4CRs and multi-channel pipettes further accelerated the rate of DKP macroarray construction, requiring only 12 hours from start (initial ester loading) to finish (DKP isolation). The use of volatile reagents for the deprotection and cyclization steps generated a sizable library (400-member) of spatially addressed DKPs in high yields and purities. We found that compounds could be eluted from the macroarray and evaluated in solution-phase biological assays in one-step, eliminating time-consuming isolation and stock solution generation procedures. Such biological testing of the DKP library uncovered six compounds capable of inhibiting V. fischeri luminescence by greater than 80% at 500 μM. These compounds should prove useful for the elucidation of the mechanism of DKP-modulated luminescence inhibition in V. fischeri. Overall, this work serves to further underscore the utility of the macroarray platform for the efficient synthesis and biological evaluation of focused small molecule libraries, and will enable future chemical probe research.

Experimental Section

Macroarray Synthesis

All chemical reagents were purchased from commercial sources (Alfa-Aesar, Aldrich, and Acros) and used without further purification. Solvents were purchased from commercial sources (Aldrich and J.T. Baker) and used as obtained, with the exception of dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), which was distilled over calcium hydride prior to use. Planar cellulose membranes (Whatman 1CHR chromatography paper, 20 × 20 cm squares) were purchased from Fisher Scientific and stored in a dessicator at room temperature until ready for use. Calibrated multi- and single-channel pipettemen were used to deliver all spotted reagents.

Dots were marked on a 10 × 10 cm sheet of Whatman 1CHR paper at distances 0.9 cm apart using a #2 pencil. In this format, 80 compound spots (area/SPOT = 0.3 cm2) could be accommodated on a single sheet without any detectable cross contamination. Five pieces of marked filter paper were subjected to blanket esterification with N-Fmoc-protected amino acids as described by Frank.25 N-Fmoc deprotection with 4% DBU in DMF (to minimize ester cleavage) afforded supports I (Gly, Ala, Leu, Phe, and Cph; loadings ~ 500 nmol/cm2). Aliquots (72 μL) of 2 M Boc-AA-OH (a–e) solutions in DMF were then mixed with aliquots of the corresponding neat aldehyde (18 μL; A–D). Using a multichannel pipette, 3 μL of Millipore water were spotted onto support I, followed by 2 μL of the Boc-AA-OH/RCHO mixture. Lastly, 0.75 μL of isocyanide (1–4) were spotted on top of the other reagents. The reactions were allowed to proceed at room temperature for 25 min; after which time, the supports were washed to yield 20-member Ugi macroarrays II. N-Boc deprotection was performed on intact macroarrays II by placing them in a Pyrex crystallization dish inside a TFA desiccator for 60 min.2,4,5,7 The arrays were removed from the dessicator and allowed to vent in a fume hood, under N2, for 2 h. DKP cyclization reactions were then performed on intact macroarrays inside the Pyrex crystallization dish. A 50 mL portion of NH4OH was added to the bottom of a large Pyrex dish, the arrays (inside a smaller Pyrex crystallization dish) were placed in the large Pyrex dish, and the large Pyrex dish was sealed. The cyclization reactions proceeded at room temperature for 60 min to give adsorbed DKP macroarrays III.

Luminescence Inhibition Assay Format

Spots from macroarray III were punched directly into the wells of a 96-well plate (using a desktop hole-punch), and 5 μL of DMSO were added to each well for increased compound solubility. An overnight culture of V. fischeri ES114 (Δ–luxI)21 was diluted 1:10 with fresh LBS (Luria-Bertani Salt media), and an appropriate amount of OHHL stock was added to give a final AHL concentration equal to its EC50 value (5 μM). Aliquots of diluted cells (250 μL) were then added to each well (negative controls contained no AHL). Following a 4-h room temperature incubation, 200 μL aliquots were transferred to fresh, white-walled 96-well plates, and absorbance and luminescence were measured. Validation assays were performed multiple times with authentic samples in triplicate. GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0c) was used to calculate the IC50 value of GlyDd4.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH (AI063326-01), Research Corporation, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Greater Milwaukee Foundation Shaw Scientist Program, Johnson & Johnson, and DuPont for financial support of this work. H.E.B. is an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellow. J.C. was supported by a Novartis Graduate Fellowship in Organic Chemistry. We thank Prof. Edward Ruby (UW–Madison) for donations of bacterial strains and contributive discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: This document includes details on macroarray construction, purity and yield analyses, and full biological assay protocols and data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

BRIEFS. We report the SPOT-synthesis of a 400-member diketopiperazine macroarray and the evaluation of the library members as luminescence inhibitors in Vibrio fischeri.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackwell HE. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowman MD, Jeske RC, Blackwell HE. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2019–2022. doi: 10.1021/ol049313f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin Q, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4455–4458. doi: 10.1021/ol051684o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman MD, Jacobson MM, Blackwell HE. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1645–1648. doi: 10.1021/ol0602708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman MD, Jacobson MM, Pujanauski BG, Blackwell HE. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4715–4727. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Q, Blackwell HE. Chem. Commun. 2006:2884–2886. doi: 10.1039/b604329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman MD, O’Neill JC, Stringer JR, Blackwell HE. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML. Mol. Divers. 2000;5:289–304. doi: 10.1023/a:1021365402751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad C. Peptides. 1995;16:151–164. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)00017-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson B, Lloyd GK, Miller BR, Palladino MA, Kiso Y, Hayashi Y, Neuteboom STC. Anti-Cancer Drug. 2006;17:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000182745.01612.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Comb. Chem. High T. Scr. 2007;10:857–876. doi: 10.2174/138620707783220365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer PM. J. Pept. Sci. 2003;9:9–35. doi: 10.1002/psc.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulme C, Morrissette MM, Volz FA, Burns CJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:1113–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szardenings AK, Harris D, Lam S, Shi LH, Tien D, Wang YW, Patel DV, Navre M, Campbell DA. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:2194–2200. doi: 10.1021/jm980133j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szardenings AK, Antonenko V, Campbell DA, DeFrancisco N, Ida S, Shi LH, Sharkov N, Tien D, Wang YW, Navre M. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:1348–1357. doi: 10.1021/jm980475p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt PG, Allen MJ, Borthwick AD, Davies DE, Exall AM, Hatley RJD, Irving WR, Livermore DG, Miller ND, Nerozzi F, Sollis SL, Szardenings AK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:2579–2582. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holden MTG, Chhabra SR, de Nys R, Stead P, Bainton NJ, Hill PJ, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D, Rice S, Givskov M, Salmond GPC, Stewart G, Bycroft BW, Kjelleberg SA, Williams P. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:1254–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degrassi G, Aguilar C, Bosco M, Zahariev S, Pongor S, Venturi V. Curr. Microbiol. 2002;45:250–254. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1432–1447. doi: 10.1039/b703021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Neill J. Campbell, Lin Q, Geske GD, Blackwell HE. 2009. submitted.

- 21.Lupp C, Urbanowski M, Greenberg EP, Ruby EG. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:319–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.t01-1-03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007;2:315–320. doi: 10.1021/cb700036x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpino LA, Han GY. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:3404–3409. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bray AM, Maeji J, Jhingran AG, Valerio RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:6163–6166. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank R. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.