Lipid bilayers that define the boundaries of cells and regulate intra/extracellular trafficking of ions and proteins have been a source of inspiration for the development of biomimetic materials. [1] For instance, liposomes have been extensively explored as carriers for drug delivery. [2] Furthermore, lipid membranes have been used as templates for the assembly of receptor signaling complexes [3] and the in vitro immunological study of cellular receptors. [4] Recently, electrospinning has been employed to engineer three-dimensional, high-surface-area lipid membranes composed of micrometer-diameter lecithin fibers. [5] Such lipid membranes may find important applications in biosensing and tissue engineering, but their poor durability adversely affect these potential applications. [6] Efforts to improve the material stability of phospholipid membranes, by polymerizing the lipids or incorporating additives, have been met with limited success. [6,7]

Compared to phospholipids, cholesterol possesses significantly increased stability, and is often included in phospholipid vesicles to enhance their durability. [8] Its small head groups and stiff sterol rings promote the cholesterol-cholesterol and sphingolipid-cholesterol interactions, leading to the formation of liquid-ordered microdomains and the anchoring of membrane proteins in the plasma membrane. [9] Recent studies revealed that most plasma membrane-bound proteins are clustered into cholesterol-enriched islands that are attached to the cytoskeleton. [10] Cholesterol also directly regulates the formation of the actin cytoskeletons via Src kinase-mediate Rho activation and caveolin phosphorylation. [11] Despite its significant structural and biological functions, a number of drawbacks have hampered a full exploration of cholesterol as a lipid membrane material. For instance, cholesterol does not possess the amphiphilicity of phospholipids, which is critical for the spontaneous self assembly of lipid bilayers. Additionally, the lack of charged groups presents a challenge to electrospinning of natural cholesterol into fibrous lipid membranes.

In this study, we propose the synthesis of polymerizable cholesteryl-succinyl silane (CSS) and the electrospinning of stable, CSS-based, nanofibrous lipid membranes. As illustrated in Figure 1a, a triethoxysilyl head moiety replaces the reactive hydroxyl group of natural cholesterol in the design of the organic-inorganic hybrid CSS. The triethoxysilyl head of CSS can be hydrolyzed and negatively charged in acidic conditions, rendering CSS amphiphilic. The hydrolysis and polymerization of the triethoxysilyl groups allow CSS molecules to form wormlike micelles at the critical concentration. As a result, a polysiloxane network forms, improving the mechanical properties of the micelles. This organic-inorganic hybridization strategy [12] was used to create liposomal cerasomes with enhanced stability for light harvesting [13] and drug delivery. [14] Here, we envision that the hydrolyzed and charged triethoxysilyl groups of CSS may enable the formation and entanglement of wormlike micelles and the electrospinning of CSS solutions into fibrous membranes at the critical concentrations. We further hypothesize that the resulting CSS lipid membranes may retain the ability of natural cholesterol to functionally immobilize membrane proteins such as antibodies.

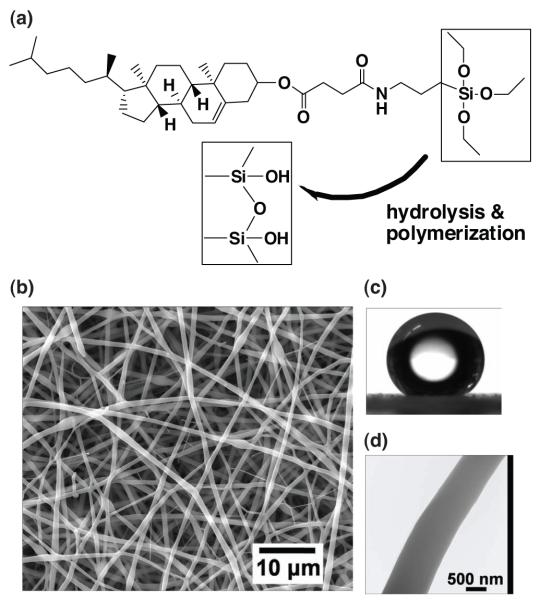

Figure 1.

A combined sol-gel and electrospinning process for engineering nanofibrous CSS membrane. (a) The chemical structure of CSS and schematic of CSS hydrolysis and polymerization prior to electrospinning. (b) SEM images of electrospun CSS nanofibers. (c) Water contact angle images. (d) TEM images.

We employed a combined sol-gel and electrospinning process for the engineering of CSS nanofibrous membranes. Following a strategy detailed in Figure S1, CSS was synthesized and analyzed using IR spectroscopy (Figure S2). In particular, the carbonyl stretching band of the carboxyl group at 1710 cm−1 disappeared after conjugating cholesterol with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane, indicating a carboxylation of cholesterol. Additionally, the emergence of amide I bands at 1642 cm−1 and new bands at 1100 cm−1 [ν (SiO), ν (CC) [15] and ρ (CH3) [16]] confirmed the replacement of the hydroxyl group of cholesterol with the triethoxysilyl head in CSS. The CSS solutions in acidic THF were incubated for 8 h, allowing for the hydrolysis and polymerization of the triethoxysilyl groups. The CSS hydrolysis was confirmed by IR spectroscopy (Figure S3). Compared to the CSS powders, bands at 1308 [δ(CH2)], 1102[ν(CC) and ρ(CH3)], 1007 [ν(CC)], and 958 cm−1 [(ρ(CH3)] were greatly weakened in the CSS fibrous membranes, suggesting the hydrolysis-induced removal of methylene and methyl groups.

Following the CSS hydrolysis and polymerization, concentrated solutions in THF were electrospun into nanofibrous lipid membranes. Unlike high molar weight polymers, the electrospinning of low molar mass organic molecules proves to be challenging due to their weak chain entanglement in solutions. It has been proposed that in the electrospinning of concentrated phospholipids the entanglement of wormlike micelles may provide an alternative mechanism for overcoming the surface tension and suppressing the instability of the solution jet, thereby leading to the formation of fibrous lipid membranes. [5] Consistent with the phospholipid study, [5] the concentration of CSS solutions greatly influences the formation and morphology of fibrous membranes (Figure S4). At a concentration of 46% w/w, the electrospraying of droplets with short filaments was evident. Beaded fibers were obtained from the electrospinning of 64% w/w CSS solutions. At a concentration of 68% w/w, the formation of nearly bead-free nanofibers suggests that the break-up of the CSS solution jet into droplets was largely suppressed by the enhanced micelle entanglement. However, if the viscosity of CSS solution is too high, some jets of CSS solutions may not be fully stretched by the electrostatic force, leading to the recurrence of beads-on-a-string structures (Figure S4d). This phenomenon has also been observed in the electrospinning of recombinant protein. [17]

Other electrospinning parameters, such as voltage and working distance, also greatly affect the microarchitectures of an electrospun CSS membrane. At a fixed working distance of 12 cm, bead-free fibers were obtained from the electrospinning of 68% w/w solution at a voltage of 5 kV or 9 to 11 kV, while beaded fibers were formed at voltages of 6–8 kV and 12–15 kV (Figures S5). It is well known that a minimum electrical field is needed to suppress the Rayleigh instability and that the poly mer solution jet becomes unstable again under very high electric fields due to the conducting instability. [18] Accordingly, there exists a window within the electric field, permitting the electrospinning of bead-free fibers. However, it remains unresolved as to why the electrospinning of CSS fibers displayed two windows in electric field, i.e., 5 kV or 9 to 11 kV. After a systematic study, CSS nanofibrous membranes were electrospun from the CSS solution at a concentration of 68% w/w, a voltage of 9 kV, and a working distance of 12 cm. The resulting CSS fibers have diameters ranging from 100 nm to 1.4 μm (Figure 1b). The CSS nanofibrous membranes are highly hydrophobic with water contact angles of about 144.3 ± 4.5° (Figure 1c). TEM analysis further reveals a uniform structure of the CSS nanofibers (Figure 1d), in contrast to many self-assembled, crystallized, and twisted lipid fibers formed in dilute aqueous suspension. [19] According to the chain entanglement model proposed by McKee et al. for phospholipids, [5] the extensive entanglement of the CSS micelles in a concentrated solution may prevent the micelles from breaking up into separate monomers and dimmers, and crystallizing into more ordered structures.

A schematic is shown in Figure 2a to illustrate the micelle and fiber formation and its implication on the subsequent antibody immobilization. During the 8 h incubation, the CSS molecules are hydrolyzed and polymerized to different degrees, resulting in the formation of dimmers, trimmers, and large n-mers (n > 3). Indeed, MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy confirmed that the CSS molecules were largely polymerized into dimmers and trimmers with a small fraction of large n-mers (n from 4 to 12) (Figure S7, Table S1). Monomers were also observed in the CSS fibers. The CSS trimmers and large n-mers would possess the improved ability to create entangled, wormlike micelles than the CSS monomers and dimmers. In the mixed solvent of 1 mL THF and 10 μL 37% HCl, the negatively charged polysiloxane networks would likely constitute the cores of wormlike micelles and the hydrophobic steroid tails comprise the coronas. Consequently, the electrospun CSS fibers would possess highly hydrophobic surfaces formed by the steroid tails.

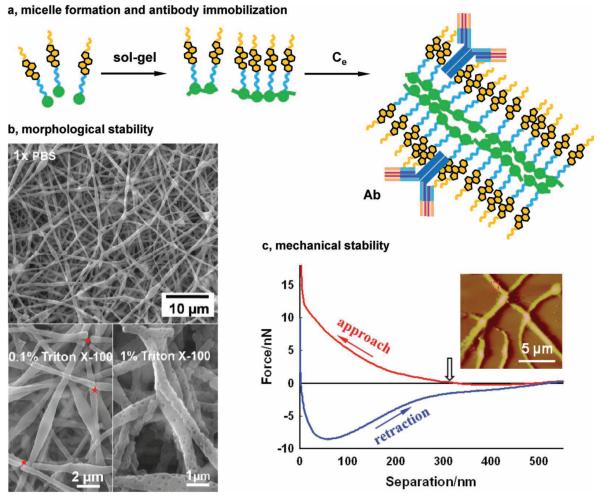

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic of CSS polymerization and micelle formation. (b) SEM images of CSS fi bers that were immersed in 1× PBS for 72 h, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1% Triton X-100 for 48 hrs. (c) A representative force-separation curve of single CSS fibers obtained via AFM nanoindentation. Inset: a typical AFM image of CSS fibers in the reflection mode.

This speculation was supported by SEM and AFM analyses. When fully hydrated in PBS, SEM analysis revealed a slight reduction in the CSS fiber diameter (Figures 1b, 2b and S6). A plausible explanation is that the CSS fibers are covered with the hydrophobic steroid tails and that the hydration of the nanofibers would enhance the molecular packaging of CSS, thereby reducing the energetically unfavourable contact of the fibers with water. Second, the force-separation curve of the CSS fibers obtained via AFM nanoindentation does not display a “jump-to-contact” process, suggesting the surface of the CSS fibers are highly hydrophobic (Figure 2c). When the AFM probe approached a less hydrophobic surface such as polypyrrole nanotube [20] and poly(L-lactic acid) nanofibers, [21] a jump-to-contact process took place. It is believed that van der Waals interactions and capillary forces induced by water condensation on the sample surfaces forced the AFM probe to contact the sample. [20,21] If the polysiloxane networks were exposed on the surface of the CSS fibers, this jump-to-contact process would occur in AFM nanoindentation. Furthermore, the exposure of the polysiloxane networks would adversely affect antibody adsorption. In contrast, the surfaces of the CSS fibers formed by the steroid tails would facilitate antibody immobilization via hydrophobic interactions and possibly direct cholesterol-receptor interactions (Figure 2a). This is consistent with our subsequent antibody immobilization and cell capture studies.

The electrospun CSS fibrous membranes displayed significantly improved morphological stability in PBS, when compared to the phospholipid fibers that were unstable in water. [5,6] When the CSS membranes were immersed in PBS for 72 h, they retained their structural integrity and surface morphologies, although salts accumulated on the surfaces of some nanofibers (Figures 2b, S6). A number of factors may contribute to the enhanced morphological stability of the CSS membranes in PBS. First, the hydrolysis and polymerization of CSS in the membranes leads to the formation of a polysiloxane network. Previously, we reported that such a network greatly improves the detergent resistance of liposomal cerasomes. [13,14] It is anticipated that the polysiloxane network has similar effects on stabilizing the CSS nanofibrous membranes against water. Second, compared to the mobile hydrocarbon chains of phospholipids, the stiff ring structures of the CSS steroid tails promotes better molecular packaging, rendering the CSS nanofibers morphologically stable. Last, the amide link between the triethoxysilyl head and steroid tail of CSS can form hydrogen bonds, further stabilizing the CSS nanofibrous membranes.

In marked contrast to their morphological stability in PBS, the CSS nanofibers display limited resistance to detergents such as Triton X-100. When the CSS membranes were immersed in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 48 h, they largely remained intact although a few broken fibers were observed (indicated by asterisks in Figure 2b). When immersed in 1% Triton X-100 for 48 h, many of the CSS nanofibers were broken. Additionally, numerous pores of several tens of nanometers in size appeared on the CSS nanofibers. Likely, the CSS monomers and possibly dimmers were not well integrated into the fibers due to the lack of chain entanglement and chemical bonding. Consequently, they can be readily removed by Triton X-100, leading to the formation of nanometer-sized pores and the breakage of the heterogeneous CSS fibers at their weakest links. The detergent resistance of the fibers may be improved by post-fabrication treatments that promote CSS polymerization. In this study, such a treatment is not necessary, because the CSS fibers are sufficiently stable in PBS for antibody immobilization and targeted cell capture.

AFM nanoindentation was performed to evaluate the mechanical properties of the CSS nanofibers (Figure 2c). Force-separation curves of the CSS fibers were analyzed by using the classical Hertz model, revealing a Young’s modulus (E) of 1.05 ± 0.32 MPa (n = 5, see details in supporting information). Notably, the CSS fibers displayed greatly improved mechanical properties compared to natural cholesterol (E ~ 0.27 MPa) and phosphatidylcholine (E ~ 0.03 MPa). [22]

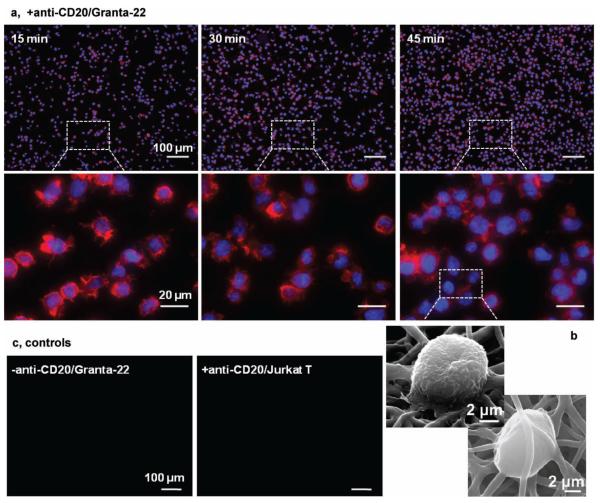

To investigate the ability of the CSS nanofibrous membranes to functionally immobilize membrane proteins, murine anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was chosen as a model material. The anti-CD20 mAb specifically recognizes the CD20 phosphoprotein expressed on the surfaces of normal B lymphocytes and B-cell lymphomas. [23] The CSS membranes were functionalized by incubating the membranes in a dilute anti-CD20 mAb solution in PBS for 1.5 h. After the functionalized CSS membrane was incubated in cell suspension for specific times, human mantle cell lymphoma Granta-22 cells at different cell densities were captured (Figure 3a). Actin cytoskeletons that regulate the shape and migration of leukocytes were examined during the attachment process of Granta-22 cells. In the first 30 min, F-actin largely accumulated around cell nuclei, while lamellipodia were formed in some cells. When more cells were captured on the CSS membranes after 45 min, cells aggregated and F-actin accumulated in lamellipodia that formed cell-cell adhesions. However, the captured Granta-22 cells retained their rounded shapes, in marked contrast to the spreading and dendrite formation of B lymphocytes induced by the immobilized anti-CD44 mAb. [24] It is believed that CD44 is a polymorphic family of adhesion molecules, interacting with the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in the mediation of cell rolling and migration. In contrast, CD20 are not known as adhesion molecules. As a result, the CD20 and anti-CD20 interactions would not drastically change the cytoskeletons, but locally pull the cell membrane, resulting in the formation of lamellipodia.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescent (a) and SEM (b) images of Granta-22 cells captured on the anti-CD20 mAb functionalized CSS membranes. The cells were fixed at indicated times, and stained for nucleus with DAPI (in blue) and for actin with phalloidin (in red). Inserts show the F-actin accumulated in the lamellipodias. Control studies (c): capturing no Granta-22 cells using the non-functionalized membranes, and no Jurkat T cells using the functionalized membranes in 45 min.

The lamellipodia formation and cell morphology were further analyzed using SEM (Figure 3b). The captured Granta-22 cells displayed two distinct types of surface morphologies. Cells immobilized on the surface of the CSS fibrous membranes displayed villous surfaces, characteristic of lymphocytes. The cells formed thin lamellipodia, generating adherent contacts with the CSS fibers. Interestingly, some cells managed to migrate into the CSS membranes and were wrapped by the CSS fibers. Some segments of the CSS fibers were nearly integrated into the plasma membranes of the trapped Granta-22 cells. Compared to the cells on the CSS membrane surfaces, the trapped Granta-22 cells possessed smooth surfaces. Although it remains unknown why the trapped cells were smooth, a cell viability of around 95% revealed by a LIVE/DEAD assay ruled out apoptosis, which might be induced by the CD20 and anti-CD20 interactions, as a factor responsible for the morphological changes (Figure S8). To understand how the captured Granta-22 cells may have moved into the CSS fibrous membrane, a thin layer of fibers were electrospun on coverslips and real-time optical imaging was pursued to analyze the cell attachment and movement on the fibrous membrane. A movie demonstrated that the captured cells were not stationary during the course of experimental observation of 65 min (video in supporting information). Rather, the cells were observed rocking back and forth on the CSS membranes, and did not move a large distance. This is consistent with the fact that CD20 are not adhesion molecules and the antigen-antibody binding would not regulate the cell cytoskeletons. In contrast, cell migration involves the dynamic assembly/disassembly of cell adhesions and the rapid restructure of the microtubule and actin cytoskeletons. [25] Based on these observations, we speculate that the captured Granta-22 cells retained their plasticity and the ability to roll on the CSS fibrous membranes, dragging the “sticky” CSS fibers. This may explain why some Granta-22 cells were trapped inside the CSS fibrous membranes. A direct observation of the migration of Granta-22 cells into a thick CSS membrane was prevented by the opacity of the membranes.

In a control study, neither Granta-22 cells were captured on the non-functionalized membranes nor were Jurkat T cells captured on the functionalized membranes (Figure 3c). Because the Granta-22 cells are CD20 positive while Jurkat T cells are CD20 negative, this study indicates that the immobilized anti-CD20 mAb retained their specificity on the CSS fibrous membranes and the antibody-antigen interactions were responsible for the capture of Granta-22 cells. The specificity of antigen-antibody interactions has been explored for the capture of various low-frequency cells for diagnosis and therapeutic treatment. For instance, microfluidic chips functionalized with anti-epithelial-cell-adhesion-molecule (EpCAM) antibodies captured a variety of rare circulating tumour cells in whole blood. [26] Previously, the coating of anti-CD34 mAb enabled stents to capture circulating endothelial progenitor cells for creating a functional endothelium and preventing stent thrombosis. [27] In these applications, antibodies were covalently coupled with the structures or an intermediate that coated the structures. To increase the cell-antibody interactions, microposts [26] and microbeads [28] were incorporated in the structures. Here, we demonstrated that, after the one-step electrospinning process, the resulting CSS membranes can be readily functionalized using antibodies without any chemical treatment. Moreover, the high-surfacearea CSS nanofibrous membranes would promote cell-antibody interactions and thus promote cell capture.

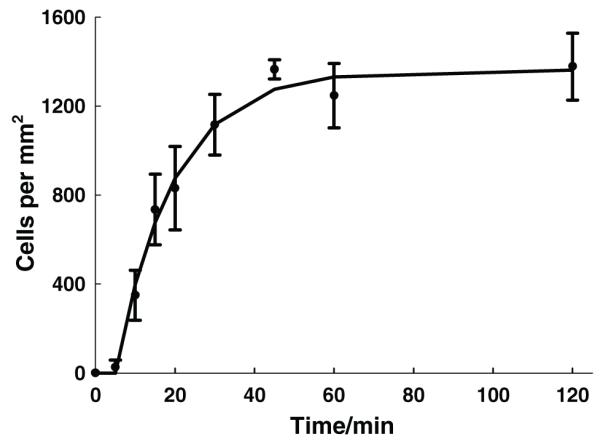

The capture of Granta-22 cells on the functionalized CSS fibrous membranes follows first-order kinetics, such that y(t) = 1363(1−e−0.0686(t−5)) for t > 5 and y(t) = 0 for t < 5, where y(t) is the cell number per mm2 and t is time (Figure 4). The small lag time of 5 min, during which the cell capture can be neglected, is likely due to cell sedimentation [29] and the formation of cellmatrix adhesions. [25,30] If excluding the lag time, the cell density of the captured Granta-22 cells on the functionalized CSS membranes saturated in 40 min at around 1363 cells per mm2, corresponding to one cell per 730 μm2.

Figure 4.

The number of the captured Granta-22 cells as a function of time. The solid line represents predictions from the first-order kinetic model, while symbols with error bars represent experimental data.

To summarize, we synthesized polymerizable cholesteryl-succinyl silane and fabricated it into stable, nanofibrous lipid membranes using a combined sol-gel and electrospinning process. In addition to the ring-structured steroid tails and the hydrogen bond forming amide links, the partial polymerization of CSS and the formation of an inorganic silicate framework render the electrospun CSS nanofibers morphologically stable in PBS without any post-fabrication treatment. The resulting CSS nanofibrous membranes are capable of functionally immobilizing membrane proteins such as antibodies. In a proof-of-concept study, anti-CD20 mAb were functionally immobilized on the CSS membranes, enabling the selective capture of B-cell lymphoma Granta-22 cells. The antigen-antibody binding did not drastically change the cell cytoskeletons, and the captured Granta-22 cells retained their plasticity and ability to roll on the CSS fibrous membrane. This work establishes a new, simple strategy to engineer stable, functional, fibrous lipid membranes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Grants from the US NIH (R21EB009801) and NSF (CMMI0856215), National High-Tech R&D Program of China (No.2007AA03Z316), and NSF of China (NSFC-30970829) are acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Zhengbao Zha, Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering IDP and Bio5 Institute, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA.

Celine Cohn, Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering IDP and Bio5 Institute, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA.

Zhifei Dai, Nanomedicine and Biosensor Laboratory, School of Sciences, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150080, China.

Weiguo Qiu, Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering IDP and Bio5 Institute, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA.

Jinhong Zhang, Department of Mining and Geological Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA.

Xiaoyi Wu, Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, Biomedical Engineering IDP and Bio5 Institute, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA.

References

- [1].a) Simons K, Vaz WLC. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004;33:269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Han XJ, Studer A, Sehr H, Geissbuhler I, Di Berardino M, Winkler FK, Tiefenauer LX. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:4466. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lian T, Ho RJY. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001;90:667. doi: 10.1002/jps.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shrout AL, Montefusco DJ, Weis RM. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13379. doi: 10.1021/bi0352769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Barklis E, McDermott J, Wilkens S, Fuller S, Thompson D. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang XW, Gureasko J, Shen K, Cole PA, Kuriyan J. Cell. 2006;125:1137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McKee MG, Layman JM, Cashion MP, Long TE. Science. 2006;311:353. doi: 10.1126/science.1119790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cashion MP, Long TE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1016. doi: 10.1021/ar800191s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hunley MT, Mckee MG, Long TE. J. Mater. Chem. 2007;17:605. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Raffy S, Teissie J. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2072. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mukherjee S, Maxfield FR. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:839. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lillemeier BF, Pfeiffer JR, Surviladze Z, Wilson BS, Davis MM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609009103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Qi MS, Liu YZ, Freeman MR, Solomn KR. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;106:1031. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Katagiri K, Hamasaki R, Ariga K, Kikuchi J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7892. doi: 10.1021/ja0259281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Matsui K, Sando S, Sera T, Aoyama Y, Sasaki Y, Komatsu T, Terashima T, Kikuchi J. JACS. 2006;128:3114. doi: 10.1021/ja058016i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dai ZF, Tian WJ, Yue XL, Zheng ZZ, Qi JJ, Tamai N, Kikuchi J. Chem. Commun. 2009:2032. doi: 10.1039/b900051h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cao Z, Ma Y, Yue XL, Li SZ, Dai ZF, Kikuchi J. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:5265. doi: 10.1039/b926367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Magoshi J, Magoshi Y, Nakamura S. Polym. Commun. 1985;26:309. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Koenig JL. J Polym. Sci.: Macromol. Rev. 1972;6:59. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Qiu WG, Huang YD, Teng WB, Cohn CM, Cappello J, Wu XY. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:3219. doi: 10.1021/bm100469w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hohman MM, Shin M, Rutledge G, Brenner MP. Phys. Fluids. 2001;13:2201. [Google Scholar]; Hohman MM, Shin M, Rutledge G, Brenner MP. Phys. Fluids. 2001;13:2221. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fuhrhop JH, Helfrich W. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1565. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Park JG, Lee SH, Kim B, Park YW. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002;81:4625. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tan EPS, Lim CT. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005:87. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Crowley JM. Biophys. J. 1973;13:711. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(73)86017-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS, Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Raab R, Newman RA, Hanna N, Anderson DR. Blood. 1994;83:435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davis TA, Czerwinski DK, Levy R. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sumoza-Toledo A, Santos-Argumedo L. J Leukocyte Biol. 2004;75:233. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zamir E, Geiger B. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3583. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Ryan P, Balis UJ, Tompkins RG, Haber DA, Toner M. Nature. 2007;450:1235. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Aoki J, Serruys PW, van Beusekom H, Ong ATL, McFadden EP, Sianos G, van der Giessen WJ, Regar E, de Feyter PJ, Davis HR, Rowland S, Kutryk MJB. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45:1574. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Furdui VI, Harrison DJ. Lab Chip. 2004;4:614. doi: 10.1039/b409366f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cheung LSL, Zheng XG, Stopa A, Baygents JC, Guzman R, Schroeder JA, Heimark RL, Zohar Y. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1721. doi: 10.1039/b822172c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Smilenov LB, Mikhailov A, Pelham RJ, Marcantonio EE, Gundersen GG. Science. 1999;286:1172. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.