Abstract

Objectives. To develop a relationship between a pharmacy management course and a mass merchandiser and to determine whether involving pharmacy managers from the mass merchandiser in the course would enhance student skills in developing a business plan for medication therapy management services.

Design. The pharmacy managers from the mass merchandiser participated in lectures, provided panel discussions, and conducted a business plan competition. Learning was assessed by means of 4 examinations and 1 project (ie, the business plan). At the conclusion of the semester, surveys were administered to solicit student input and gain insight from pharmacy managers on the perceived value of this portion of the course.

Assessment. Students’ average grade on the business plan assignment, which included the oral presentation, the peer assessment, and the written proposal, was 92.2%. Approximately 60% (n = 53) of surveyed students agreed or strongly agreed that their management skills had improved because of the participation of pharmacy managers from the mass merchandiser. All of the managers enjoyed participating in the experience.

Conclusions. The involvement of pharmacy managers from a mass merchandiser enhanced student learning in the classroom, and managers felt that their participation was an important contribution to the development of future pharmacists.

Keywords: medication therapy management services, business plan, pharmacy management, business

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy has evolved from a profession that primarily involved dispensing medications to one focused on providing patient care. This is reflected by colleges and schools movement away from the bachelor of science (BS) in pharmacy degree to the more clinically focused doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree as the first professional degree. This change has been recognized by the profession as well as by policymakers. In 2003, Congress enacted the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA), which was implemented in 2006. This was a monumental moment for the pharmacy profession because the Act requires prescription drug plan sponsors to have a medication therapy management (MTM) program designed to assist Medicare Part D enrollees with multiple chronic diseases, multiple medications, and high drug costs. The MMA specifically identified pharmacists as providers who could be compensated for providing these services.1 This was the first time that pharmacists were recognized as reimbursable providers, offering them an opportunity to be innovative in their delivery of these services, which are designed to assess and evaluate the patient's medication therapy regimen in its entirety rather than focusing on an individual medication product.2

Along with the provider status earned by the profession, educational agencies updated the training that PharmD programs are required to provide in the areas of social and administrative sciences. Educational standards require that pharmacy students be trained to manage pharmacy operations. The 2004 Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes Supplements suggests that students learn how to “apply the principles of business planning to develop a business plan that supports the implementation and provision of pharmaceutical care services, identifies and acquires necessary resources, and assures financial success of the practice.”3 The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education further recommends that students be trained to “manage a successful patient-centered practice (including establishing marketing, and being compensated for medication therapy management and patient care services rendered).”4

Professional organizations in pharmacy also have acknowledged management-related skills as areas for development in training pharmacy students to meet the needs of the profession. In 2000, the American Pharmacists Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism published a White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism. In the publication, a recommendation was made for educational programs to “incorporate disciplinary teamwork, communication, leadership, critical thinking, and listening skills into the curriculum.”5 The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Statement of Professionalism also identifies leadership as a characteristic of a professional.6

In response to the educational demands of pharmacists, the American Pharmacists Association now offers a certificate training program entitled “Delivering Medication Therapy Management Services in the Community” to enhance pharmacists’ clinical expertise in evaluating complicated medication regimens. One of the program's goals is to increase the number of pharmacists establishing MTM services.7 The changes in governmental policy, requirements by educational agencies, and recommendations by professional organizations have resulted in faculty members in the area of social and administrative sciences moving with the profession, as evidenced by the development of an elective course on MTM services at the South Carolina College of Pharmacy.8

During the summer of 2007, a representative from a mass merchandiser (Wal-Mart) pharmacy approached the dean of the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences to express interest in participating in the college's pharmacy management course to encourage student participation in entrepreneurship. The college as well as the mass merchandisers’ local district pharmacy managers who oversaw operations of multiple pharmacies in Texas recognized an opportunity to provide pharmacy students with insight into the more practical side of pharmacy management. The company wanted to participate to an extent that would allow students to earn scholarships. The company would support traditional lectures on selected topics based on interest and availability by providing panel discussions and also would conduct a business plan competition for monetary awards. Because developing a business plan was already part of the student assessment for the course, the mass merchandiser felt this approach would allow them to participate without interfering with the established layout of the course, while exposing students to the “real-life” experience of submitting a proposal and competing for funding.

This paper describes revisions made to the required pharmacy management course at Texas Southern University to respond to the demands of the profession. The update to the instructional design was related to the professional recommendations that would enhance students’ abilities in teamwork, communication, leadership, critical thinking, and the ability to develop a business plan for an MTM service and manage the service. To achieve these goals, students were assigned to work in groups to develop a business plan for an MTM service based on the design of a mass merchandiser community pharmacy. Each group's business plan would be orally presented to the course coordinator and subsequently submitted to the participating pharmacy managers for review and scholarship consideration. This paper describes the process of developing a relationship between a mass merchandiser pharmacy and an educational entity and explores whether involving practicing pharmacy managers from a mass merchandiser in a pharmacy management course enhances students’ ability to develop a business plan for MTM services. This study was conducted prior to the implementation of introductory pharmacy practice experiences and revision of the PharmD curriculum.

Previous literature describes the use of pharmacy managers as mentors in the business plan development process.9 The current approach to enhancing students’ learning is different because it involves pharmacy managers in the classroom lecture portion of the course. It also gives students the unique opportunity to compete and present/sell their business idea to actual managers and receive compensation for it (in the form of scholarships/funding), just as the process occurs in the “real world.” The hypothesis was that including practicing pharmacy managers in the course would enhance student learning. Outcomes for the doctor of pharmacy program addressed by this redesign included establishing rapport with pharmacy staff members; complying with regulations; using information management technology; understanding business planning needs for MTM; communicating orally and in writing; carrying out duties in accordance with legal, ethical, socio-cultural, economic, and professional guidelines; and providing resources to improve medication availability and therapeutic outcomes of medication use.

DESIGN

Texas Southern University, located in Houston, is one of the nation's largest historically black colleges and universities. Classes are culturally diverse with approximately 120 students enrolled annually. The PharmD program is housed in a college of pharmacy and health sciences.10 The pharmacy management course is a required 3-hour-credit course taught 2 days a week for 90 minutes during the fall semester of the third year in the PharmD degree curriculum. The only other pharmacy administration courses students receive prior to this course are Ethics and Biostatistics, which provide minimal exposure to management-related topics. The only students who have been exposed to pharmacy operations at this point in the curriculum are those who have worked part-time in a pharmacy.

The course was redesigned to prepare students to recognize entrepreneurship as an option in pharmacy practice and to demonstrate an understanding of basic management principles and how they apply to pharmacy environments. After completing the course, students were expected to be able to describe the role of operations management, technology and information systems, organizational behavior, human resources management, and business laws in pharmacy practice; to discuss budgeting considerations; and to explain pharmacist reimbursement for value-added services. Students also were expected to apply the theory learned in the course to develop a business proposal for MTM services.

In 2004, the pharmacy management course was revamped and updated to be more inclusive of operations management in various settings, as opposed to focusing primarily on retail pharmacy. In 2005 and 2006, the course assignments were updated to require student groups to submit business plans for a pharmacy venture, whether dispensing-oriented or service-oriented. Following MMA implementation, the assignment was further revised to require service-oriented business plans, based on the college's revision of outcomes to specifically address MTM services and recommendations made by professional organizations.

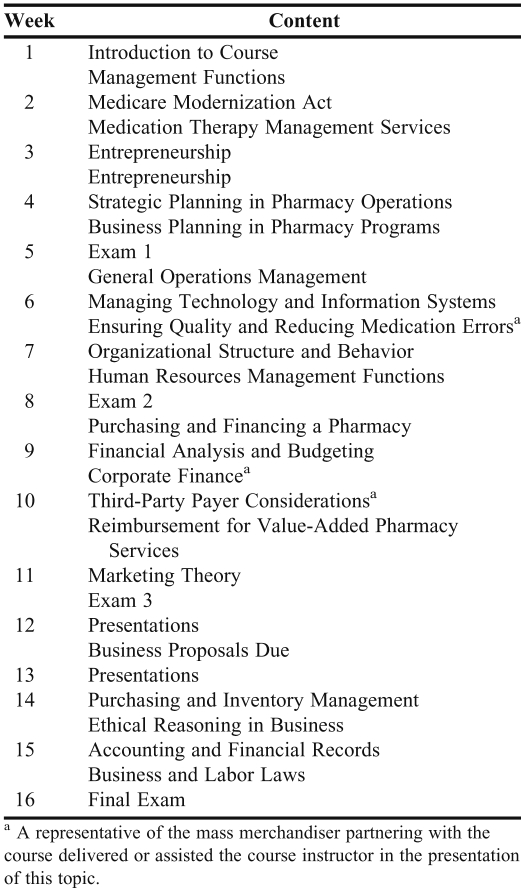

The curricular design of the pharmacy management course was updated to enhance the skills students would gain from the course. To enhance practical application of the material, the course combined traditional classroom lectures with panel discussions and presentations on various management topics (Table 1) by the mass merchandiser's district pharmacy managers. Direct involvement of active full-time pharmacy managers was expected to help students understand the relevance of the information presented and receive valuable feedback on potential business plan ideas from decision-makers. New books selected for the course included The Essentials of Pharmacy Management by Shane P. Desselle and David P. Zgarrick and How to Develop a Business Plan for Clinical Pharmacy Services: A Guide for Managers and Clinicians by Glen T. Schumock.

Table 1.

Topics Covered in a Pharmacy Management Course That Partnered With a Mass Merchandiser Pharmacy

At the beginning of the 2007 fall semester, students were informed about the required business plan assignment, and that representatives from a mass merchandiser would be participating in some classes and holding a business plan competition for interested students. Although submitting the business plan was required for a grade in the course, participation in the competition was optional.

In preparation for the course, the mass merchandiser's representative was provided with the course syllabus, a description of the business plan assignment, and a copy of the course textbook, all of which were shared with the pharmacy managers. For the first 11 weeks of the semester, students were provided 90-minute lectures in a traditional format on pharmacy management topics that would assist them in preparing their business plans. (Table 1). The mass merchandiser provided input in 3 lectures based on the relevance these topics had to the community setting to allow for their participation in panel discussions. The course coordinator provided a 60-minute lecture, “Medication Errors and Quality Assurance and Third Party Considerations,” which was followed by a 30-minute panel discussion by a representative of the mass marketer and some of its district pharmacy managers. Because of their management roles and ability to demonstrate relevance of the topic, they also provided a 60-minute lecture and 30-minute panel discussion on corporate finance. The representative for the mass merchandiser provided the lecture, which was supported by district managers who provided input during the presentation and a more structured panel discussion at the end.

The managers who participated in the panel discussions were licensed pharmacists who had previously worked in the pharmacy at one of the mass merchandiser's stores at some point in their careers. Most of the participating managers were directors, all exceeded store-level management, and several had had formal training in business administration, including graduate degrees.

Approximately 4 weeks after the 15-week semester began, students were randomly assigned to groups of 5 to work on a business plan. The business plan project allowed students to apply the theory they had learned during the semester. Business plans were submitted to the course coordinator for assessment during the 12th week. Students who wanted their plan to be reviewed by the pharmacy managers were asked to submit 2 copies (1 for the course coordinator and 1 for the mass merchandiser). This allowed the course coordinator to review and make comments on the business plan without biasing the assessment of the pharmacy district managers. Students also were asked to submit their peer assessments for each group member when they submitted their business plans.

At the end of the semester, students received a grade for their business plans and the additional copies of the business plans were forwarded to the pharmacy district managers. The business plans were reviewed by 5 pharmacy district managers based on their own criteria, which were similar to those used by the course instructor to assess the plans for a grade but included greater emphasis on practical implementation in their stores. Based on their scoring criteria, the pharmacy managers selected the top 5 business plans.

The top 5 teams, which were announced to the students at the beginning of the following semester, were given an opportunity to provide a 15- to 20-minute oral presentation of their proposals to the managers on a designated weekday. That evening, an awards banquet was held to announce the winners. Each member of the first- and second-place teams received a monetary award and each member of the top 5 teams received a plaque.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Student Performance

Learning was assessed based on students’ performance on the business plan and 4 examinations.

Business plan assignment. Business plans were assessed in 3 categories: teamwork, oral communication, and written communication. Rubrics were used to measure student performance on the business plans to ensure scoring was efficient and objective.11 The course coordinator used an oral presentation rubric to assess each student's oral communication based on their participation in the group presentation of the business plan. Teamwork was evaluated for each individual by the 4 other group members using a peer assessment rubric. Written communication was evaluated by the course coordinator using a business plan assessment form, with specific content determined by the business plan that each group had submitted. The written proposal represented 60% of the total grade, while the peer assessment and oral presentation represented 15% and 25%, respectively.

Each rubric was worth 100 points and contributed a varying percentage of the student's total grade for the business plan. Student performance was deemed successful if the following criteria were met:

80% of the students received ≥85 points on the oral presentation rubric

80% of the students received ≥85 points on the peer assessment rubrics

80% of the groups received ≥8 points in at least 8 of the 10 sections on the written-proposal assessment form.

Because this was the first time the current approach had been used in the course, 80% was chosen as the standard measure of success, to allow room for improvement over the 85% measure of success used on the objective examinations. Numeric values were added to columns on the rubrics to allow for score computation.12,13

The average grade on the business plan assignment, which included the oral presentation, the peer assessment, and the written proposal, was 92.2%. Eighty-five percent (n = 102) of the students received 85 points or more on the oral presentation, and 97.5% (n = 117) received 85 points or more on the peer assessment. Only 4 groups failed to earn 8 points or more in 8 of the 10 sections on the written proposal assessment form. Therefore, 83.4% of the groups met the goal.

Examinations. Four 40-question multiple-choice examinations were administered to students after approximately every 6 class meetings (4 examinations during the semester). Students were considered to have mastered the information presented in the course if they received a passing grade of at least 75% on the examinations. The goal was for 85% of the students to receive a grade of 75% or greater on each examination administered.

The average grades were 80.9% on the first examination, 74.6% on the second examination, 84% on the third examination, and 93.8% on the fourth examination. The goal of 85% of the students receiving a 75% or higher grade on the examination was achieved for the first examination with 85% of the students meeting the expectation, the third examination with 87.5% meeting the expectation, and the fourth examination with 100% meeting the expectation. Only 54.2% of the students met the expectation on the second examination.

Assessment of Course Redesign

In addition to student performance, success of the course redesign was evaluated based on feedback on the course from students, the mass merchandiser, and the course coordinator, and on the willingness of the mass merchandiser to participate again. Student feedback on the course redesign was evaluated using an electronic survey instrument developed by the course coordinator and validated with other pharmacists and pharmacy students. Because the survey was conducted in an educational setting on instructional techniques, it was exempt from the institutional review board. Students were informed of the survey by means of Blackboard (Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC) and by announcements in class, and were given 3 weeks to participate. The survey instrument used a 5-point Likert scale with answers ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and included some yes/no questions with space provided for comments. Questions focused on students’ views about the mass merchandiser's participation, the business plan assignment, and the awards banquet. The survey was administered through Surveymonkey.com (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA) and student responses were anonymous. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data.

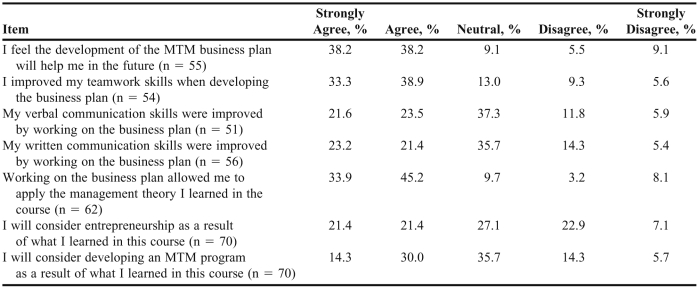

Of the 120 students taking the course, 86 participated in the survey, yielding a response rate of 71.7%. Not all respondents answered every survey question. Approximately 76% (n = 55) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that the experience of developing a business plan would help them in the future. Approximately 72% (n = 54) agreed or strongly agreed that developing the business plan improved their teamwork skills, while 45.1% (n = 51) and 44.6% (n = 56) agreed or strongly agreed that the business plan assignment improved their verbal communication and written communication skills, respectively. Approximately 80% (n = 62) of the students felt that working on the business plan allowed them to apply the management theory learned in the course (Table 2).

Table 2.

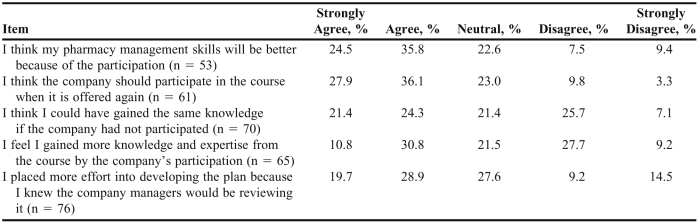

Student Views of Mass Merchandiser Course Participation

Approximately 60% (n = 53) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that their management skills would be better because of the mass merchandiser's participation (Table 3). Sixty-four percent (n = 61) agreed or strongly agreed that the mass merchandiser should participate in the course again. Slightly more than 45% (n = 70) agreed or strongly agreed that they could have acquired the same knowledge without the mass merchandiser's participation, while 41.6% (n = 65) felt that they gained more knowledge and expertise because of it.

Table 3.

Student Views of the Business Plan Assignment and Course Impact

Mass merchandiser feedback was gathered by means of verbal feedback and e-mailed survey instruments. Survey instruments were e-mailed to 8 managers and 4 completed and returned them. The mass merchandiser representative was responsible for e-mailing and retrieving the survey instruments. The survey used a 5-point Likert scale with answers ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Questions focused on the relevancy of the topic they presented to students to their job, feelings about their participation as it related to developing pharmacy students, and the impact of the experience on the relationship of the college with the mass merchandiser. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data.

Although the mass merchandiser's willingness to continue participating in the course and conduct the business plan competition provided initial confirmation that the representative and pharmacy managers were satisfied with their involvement, the follow-up survey provided more insight about their overall experience. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that the topics they presented were relevant to their positions and all strongly agreed that they enjoyed the experience and felt it had a positive impact on their relationship with the college. Additionally, they all strongly agreed that their participation provided them the opportunity to expose pharmacy students to pharmacy management and felt their participation was an important contribution to the development of future pharmacists.

DISCUSSION

Participation of the mass merchandiser in the pharmacy management course enhanced learning for the students and was a valuable experience for the pharmacy managers. In each of the metrics used to assess student success on the business plan assignment (ie, oral presentation, peer assessment, and written proposal), student performance exceeded the goal. Additionally, students met the performance goal with the exception of the second examination. Historically, this tends to be an examination on which students do not perform as well for reasons that are unclear.

While the majority of students did not feel they would not have learned without the mass merchandiser's participation, they did feel they gained more because of the merchandiser's participation. Students felt that developing a business plan helped them to apply the management theory learned in the class lectures, and this was an overarching goal of the assignment. In a similar course review of pharmacy managers serving as coaches for teams developing business plans for pharmaceutical care services, the authors found that students showed significant improvement in their perceived ability to perform all business plan activities after completing the course.9

Since 2007, the business plan competition has continued, with changes based on student and mass merchandiser feedback and course coordinator experience. This feedback has resulted in changes related to scheduling, the business plan submission process, and the types of proposals accepted for participation in the competition. Changes also were made to the business plan assignment itself based on student feedback and course coordinator input. These changes were related to requirements for the assignment, grading of the assignment, and scheduling of the oral presentations.

The most significant change related to the business plan competition has been timing of the competition. The first year the competition occurred in a banquet-style format on a Friday evening. Student feedback revealed that more students would have liked to attend but could not because of their work schedules. In response, the competition subsequently has been held at the beginning of the spring semester during class time, enabling all students in the class to participate. The process for distribution of the business plans to the mass merchandiser has been streamlined to allow students to directly e-mail their business plans to a representative, who then forwards them to the pharmacy managers for review. Students also have been encouraged to think beyond traditional chronic disease states in developing a business plan, as many are based on diabetes.

To minimize perceived problems associated with acceptance of corporate gifts by the college, other changes have been made to the course and the business plan assignment. Feedback from student surveys revealed that students felt obligated to use only the pharmacies of the mass merchandiser when developing their business plans. Students are now instructed that they may develop a business plan for an MTM service based on any existing community pharmacy and that they may participate in the competition even if the plan is not based on a store from the mass merchandiser.

To reduce the likelihood of other constituents perceiving relationships with the mass merchandiser as preferential and to expose students to diverse areas, more guest lecturers from various pharmacy environments have been invited to participate in the course.14 These environments include grocery retail, independent retail, hospital, and long-term acute care, giving the students a range of perspectives on pharmacy management.

Changes related to grading the business plan assignment also have been made. In calculating the total grade, the percentage value for the peer assessment and oral presentation has varied throughout the years. Initially, the peer assessment counted for 15% and the oral presentation counted for 25%. However, the course coordinator perceived that students were unjustly giving each other full credit without giving true assessments, which essentially amounted to a guaranteed 15 points on the total score. To address this problem, the peer assessment credit was reduced to 10% and the oral presentation was increased to 30% in 2008. This change was reversed in 2009 based on some students feeling that 10% for peer assessment did not give them a voice in the overall assessment. In response, students are now verbally encouraged to give honest assessments, and this approach seems to be effective. The peer assessment forms historically have been submitted on the same day as the business plan. However, because students expressed that this did not allow them to fully assess their classmates’ contributions, peer assessments are now submitted on the day the group gives their oral presentation. Oral presentations and business plans are now due during the last 2 weeks of the semester, so that the business plan assignment is truly the culmination of the course.

Each year, input is solicited from the students and the mass merchandiser on how the course and the business plan competition can be improved. The course will continue to be refined through the feedback received from this ongoing method of evaluation.

SUMMARY

Involvement of the pharmacy managers from a mass merchandiser enhanced student learning in the classroom, and pharmacy managers felt their participation was important in the development of future pharmacists. Students felt that working on a business plan would help them in the future and also thought it helped them apply what they had learned. Involving external practicing pharmacy managers in the course to enhance student learning helps prepare students to meet future challenges as the profession evolves and the demand for pharmacy managers increases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Sharon Early, PharmD, Regional Talent Specialist, Wal-Mart/Sam's Club, for working with the college since 2007 to coordinate the business plan competition.

REFERENCES

- 1.Public Law 108-13. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. HR 1. December 8, 2003. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MMAUpdate/downloads/PL108-173summary.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2011.

- 2.American Pharmacists Association and National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in community pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service (version 2.0) J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):341–353. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.08514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Advisory Panel on Educational Outcomes. 2004 Education Outcomes, revised version. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed June 13, 2011.

- 5.American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy – American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on professionalism. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65(2):172–174. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Pharmacists Association. Delivering medication therapy management services in the community. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Delivering_Medication_Therapy_Management_in_the_Community. Accessed June 13, 2011.

- 8.Kuhn C, Powell PH, Sterrett JJ. Elective course on medication therapy management services. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3):Article 40. doi: 10.5688/aj740340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks C, Siganga W, Shah B. Enhancing pharmacy student business management skills by collaborating with pharmacy managers to implement pharmaceutical care services. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):Article 94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Texas Southern University. About TSU. http://www.tsu.edu/about. Accessed June 13, 2011.

- 11.Schneider FJ. Rubrics for teacher education in community college. The Community College Enterprise. 2006;12(1):39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Department of Physics at Illinois State University. JDC peer participation scoring rubric. http://www.phy.ilstu.edu/pte/311content/lessonstudy/jdc_peer_rubric.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2011.

- 13.Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills: The Technology Applications Center for Educator Development. Oral presentation rubric. http://assessment.udayton.edu/how-to%20tips/Rubrics/presentation%20rubric%20-%20tcet.htm. Accessed August 19, 2011.

- 14.Piascik P, Bernard D, Madhavan S, Sorensen TD, et al. Gifts and corporate influence in doctor of pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(4):Article 68. doi: 10.5688/aj710468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]