Abstract

The present study examined the extent to which anxiety sensitivity (AS) at treatment entry was related to prospective treatment dropout among 182 crack/cocaine and/or heroin dependent patients in a substance use residential treatment facility in Northeast Washington DC. Results indicated that AS incrementally and prospectively predicted treatment dropout after controlling for the variance accounted for by demographics and other drug use variables, legal obligation to treatment (i.e., court ordered vs. self-referred), alcohol use frequency, and depressive symptoms. Findings are discussed in relation to the role of AS in treatment dropout and substance use problems more generally.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, heroin, crack/cocaine, drug treatment, treatment completion

Substance use disorders are widespread among the general population and associated with significant economic, societal, and personal costs (Grant et al., 2004; Regier et al., 1990). Though many individuals seek treatment for such problems, a large percentage dropout of treatment prematurely and relapse soon after (Hubbard, Craddock, Flynn, Anderson, & Etheridge, 1997; Ravndal & Vaglum, 2002; Simpson, Joe, & Brown, 1999). A growing number of investigations have empirically explored potential predictors of substance use treatment dropout, including demographics (Maglione, Chao, & Anglin, 2000), psychiatric symptoms (Hattenschwiler, Ruesch, & Modestin, 2001), emotional symptoms (McCusker, Stoddard, Frost, & Zorn, 1996), drug use severity (Ravndal & Vaglum, 1991), and a variety of social-cognitive variables (e.g., social support, self-efficacy, motivation to quit; Blanchard, Morgenstern, Morgan, Labouvie, & Bux, 2003; Daley, Salloum, Zuckoff, & Kirisci, 1998; Mertens & Weisner, 2000; Messina, Wish, & Nemes, 2000). However, due to little agreement on the consistency or the generalizability of these findings (Claus, Kindleberger, & Dugan, 2002; McFarlain, Cohen, Yoder, & Guidry, 1977; Nemes, Wish, & Messina, 1999; Alterman, McKay, Mulvaney, & McLellan, 1996; Agosti, Nunes, Stewart, & Quitkin, 1991), it has become apparent that it is important to identify and examine other constructs that may contribute to the understanding of the processes involved in a patient’s decision to remain in or prematurely leave residential treatment.

Building from contemporary models of psychological vulnerability which suggest that the ways in which individuals evaluate and respond to internal events may influence risk for a variety of negative outcomes (e.g., Barlow, 2002), there is good reason to explore theoretically-relevant cognitive factors reflecting a hypersensitivity to aversive events in an effort to better understand treatment dropout processes among drug using populations (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Zvolensky, 2005). One such cognitive vulnerability variable that may prove to be especially useful in understanding premature treatment attrition is that of anxiety sensitivity (AS). AS is an individual difference factor reflecting the fear of anxiety-related sensations, which arise from a belief that such sensations have harmful personal consequences (Reiss & McNally, 1985). The global AS construct encompasses fears of the physical, mental, and social consequences of anxiety-related sensations (Zinbarg, Barlow, & Brown, 1997), all of which can function to theoretically amplify preexisting anxiety (Reiss, 1991). AS has assumed an increasingly important, clinically-relevant role as a cognitive-based vulnerability factor for emotional disorders (McNally, 2002; Taylor, 1999). Indeed, recent studies suggest AS is related to maladaptive forms of emotional processing and affect regulation such as catastrophic thinking (Zvolensky, Forsyth, Bernstein, & Leen-Feldner, 2007; Zvolensky, Kotov, Antipova, & Schmidt, 2005), avoidance-based coping (Feldner, Zvolensky, Stickle, Bonn-Miller, & Leen-Feldner, 2006; Tull & Gratz, 2008; Zvolensky & Forsyth, 2002), as well as emotion dysregulation (Kashdan, Zvolensky, & McLeish, in press; Tull, 2006, Tull & Gratz, 2008). Further, AS has been found to be associated with a general inability to tolerate uncomfortable bodily sensations (Schmidt, Richey, & Fitzpatrick, 2006) which may place an individual at risk for worse anxiety-related outcomes. Specifically, high AS, combined with an intolerance for uncomfortable bodily sensations, has been found to be predictive of greater subjective anxious responding to a CO2 challenge (Schmidt, Richey, Cromer, & Buckner, 2007).

The recognition that AS is related to aversive anxiety states and dysfunctional aspects of emotional processing (McNally, 2002) has lead researchers to theorize that this cognitive factor may be related to the maintenance of substance use disorders (Brown et al., 2005; Morissette, Tull, Gulliver, Kamholz, & Zimering, 2007, Norton, 2001; Otto, Powers, & Fischmann, 2005; Otto, Safren, & Pollack, 2004; Stewart & Kushner, 2001; Stewart, Samoluk, & MacDonald, 1999; Tull, Baruch, Duplinsky, & Lejuez, 2007; Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005; Zvolensky, Schmidt, & Stewart, 2003). To the extent that AS reflects a sensitivity to (and is related to an intolerance of) certain internal states, individuals with greater levels of this cognitive factor may be apt to use drugs and/or alcohol to regulate affective distress. In line with predictions derived from such models, AS has been found to be related to coping-oriented motives for cigarette smoking (Brown, Kahler, Zvolensky, Lejuez, & Ramsey, 2001; Zvolensky, Schmidt et al., 2005), alcohol (Conrod, Pihl, & Vassileva, 1998; Stewart, Karp, Pihl, & Peterson, 1997; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2002), and cannabis (Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2007; Comeau, Stewart, & Loba, 2001). Additionally, AS is related to heavier alcohol use patterns (Cox, Swinson, Shulman, Kuch, & Reichman, 1993; Stewart, Peterson, & Pihl, 1995; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2001; Zvolensky, Kotov, Antipova, Leen-Feldner, & Schmidt, 2005) and may be elevated among individuals who use substances that primarily function to dampen central arousal such as heroin (Lejuez, Paulson, Daughters, Bornovalova, & Zvolensky, 2006). These data collectively suggest that AS is related to coping-oriented use patterns for numerous substances.

Recognizing the explanatory utility of AS to coping-oriented substance use and other problematic aspects of drug use behavior, researchers have theorized that this cognitive factor may increase risk for poor substance use treatment outcomes (Otto et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 1999; Zvolensky, Schmidt et al., 2005). To the extent that individuals with high AS do not have adequate psychological resources to successfully cope with such aversive events, they may be more likely to prematurely terminate substance use treatment. This research is supported by a study suggesting that AS, relative to other predictors, may have utility in identifying patients who dropout of antidepressant trials, perhaps because of a heightened sensitivity to the side effects from these medications (Tedlow et al., 1996). Likewise, data suggest that heightened AS is a risk factor for early lapse during smoking cessation (Brown et al., 2001), and the degree of change in AS has been a significant predictor of relapse among those discontinuing use of benzodiazepines (Bruce, Spiegel, Gregg, & Nuzzarello, 1995).

Building from these previous AS findings, we examined the extent to which AS at baseline (i.e., treatment entry) was related to prospective treatment dropout. This research was conducted in an inner-city residential treatment center, a setting which is especially relevant for such work given that it often includes especially difficult to treat patients and evidences especially low rates of treatment completion (SAMHSA, 2002). Further, this work adds to a relative small body of research examining AS among minority individuals and specifically minority inner-city substance users (cf. Lejuez et al., 2006). In doing so, we controlled for other theoretically-relevant factors (e.g., demographics and other drug use variables, depressive symptoms, and legal obligation to treatment) in an effort to isolate the unique variance accounted for by AS in regard to treatment dropout and to ensure such effects are not attributable to shared variance with other theoretically-relevant characteristics.

Method

Participants and Setting

Potential participants were 204 consecutive admissions to a substance use residential treatment facility in Northeast Washington DC, recruited between their 4th and 7th day at the Center. Inclusion in the present study required dependence on heroin and/or crack/cocaine; individuals not dependent on these drugs, as determined by a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) in the context of a larger study focused on crack/cocaine and heroin dependence, were excluded. Based on this criterion, 22 individuals were excluded (36.4% were dependent only on marijuana, 31.8% were dependent only on hallucinogens including PCP, and 31.8% were dependent on some combination of these three substances). No potential participant was dependent only on alcohol. Of the final sample of 182 participants, 67% were male, 94% were African American (due to a lack of variability, this variable was not considered in the analyses), and 78% were court ordered for treatment. The average age was 42.2 (SD = 7.7), the average income was $22,127 (SD = $20,263), and in terms of education, 25.4% had not completed high school, 37.9% completed high school (or GED), and 36.8% completed at least some college, technical or trade school.

The center offers four contract durations determined at admission including 30 days (n = 71; 39%), 60 days (n = 39; 21.4%), 90 days (n = 32; 17.6%), and 180 days (n = 40; 22%) and treatment involves a mix of strategies adopted from Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous, as well as group sessions focused on relapse prevention and functional analysis. The center requires complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol (methadone maintenance is not available), with the exception of caffeine and nicotine; regular drug testing is provided and any use is grounds for dismissal from the center. Admission into the Center required outside detoxification as needed prior to entry. This fact, combined with delaying recruitment into the study until at least day 4, served to limit the influence of physical withdrawal symptoms on study responses.

Measures

In addition to the drug dependence section of the SCID-IV and a demographic questionnaire, three other measures were used to index a) frequency of past year substance use prior to treatment, b) AS, and c) severity of depressive symptoms. To assess substance use frequency, participants rated frequency of use of a particular substance in the past year prior to treatment on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 = none to 5 = every day. In addition to crack/cocaine and heroin, the substances of interest here were: (a) cannabis, (b) alcohol, and (c) hallucinogens including PCP; other substances were not included due to minimal use. The approach is based off the highly reliable and valid Alcohol Use Disorders Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, DelaFuente, & Grant, 1993) and has been used for similar purposes as here in several other studies (e.g., Daughters et al., 2005; Lejuez et al., 2006). The Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Peterson & Reiss, 1992) is a reliable and valid 16-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the degree to which an individual is concerned about the possible negative consequences of arousal-based anxiety symptoms. The ASI provides a single, higher order AS factor that is composed of three lower-order factors (i.e., physical concerns, mental incapacitation concerns, and social fears of publicly observable anxiety reactions; Zinbarg et al, 1997). Given evidence that the ASI demonstrates moderate correlations with trait anxiety and neuroticism (see Lilienfeld, 1999), it was important to establish that there is a unique relationship between AS and treatment drop-out. Therefore, participants were also administered the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a reliable and valid 20-item self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the past two weeks. In addition to controlling for depression-related symptomotology, the inclusion of this measure is useful for isolating the specific contribution of AS because the CES-D is moderately to highly correlated with measures of related constructs including neuroticism (as assessed by the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire [EPQ; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1991] and the Revised NEO Personality Inventory [NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992]) and trait anxiety (as assessed by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970]), with rs ranging from .50 to .71 (see Dunkley, Blankstein, & Flett, 1997; Orme, Reis, & Herz, 1986; Schroevers, Sanderman, van Sonderen, & Ranchor, 2000).

Results

Across all contract dates, 25.3% (n = 46) dropped out of treatment1,2. As shown in Table 1, dropout status (controlling for contract duration) did not differ across age, education, gender, and income, as well as substance use frequency (past year) or current dependence across alcohol, marijuana, hallucinogens including PCP, crack/cocaine, or heroin. Dropouts compared to completers evidenced higher depressive symptoms and were significantly less likely to be court-ordered to treatment. Finally, dropouts compared to completers evidenced significantly higher AS Total, with this significant difference persisting across the subfactors for the AS Cognitive and AS Social; no difference was evident for AS Physical.

Table 1.

Key variables as a function of dropout status.

| Completer (n = 136) | Dropout (n = 46) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.10 (7.64) | 40.63 (7.39) |

| Education | 24.0% < HS < 37.8% | 23.9% < HS < 34.8% |

| Gender | 69.1% male | 60.9% male |

| Income | 49.3% < $10,000 < 50.7% | 52.2% < $10,000 < 47.8% |

| Legal Obligation** | 84.6% | 56.5% |

| Crack/cocaine Dependence | 76.5% | 87.0% |

| Heroin Dependence | 50.0% | 43.5% |

| Depressive Symptoms* | 22.14 (10.81) | 26.33 (12.75) |

| Anxiety Sensitivity* | 25.41 (11.96) | 29.80 (10.98) |

| Cognitive Subscale* | 3.52 (3.14) | 4.89 (3.53) |

| Physical Subscale | 13.99 (7.79) | 15.91 (6.81) |

| Social Subscale* | 7.89 (3.15) | 9.00 (3.06) |

Note. HS indicates High School or GED/equivalent; Depressive symptoms are taken from score on the Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale; AS indicates raw total scores from the Anxiety Sensitivity Index;

p < .05;

p < .01.

A positive association was found between AS and depressive symptoms (r = .25, p < .001). AS was not significantly associated with age, education, gender, income, and legal obligation, as well as substance use frequency (past year) or dependence across substances with the exception of a mild positive relationship between AS and alcohol frequency (r = .15; p < .05). Across the subfactors, a correlation existed between depressive symptoms and both AS cognitive and AS Physical (r = .31, p < .001; r = .22, p < .001), but not the social subscale (p > .15). Controlling for contract duration did not change any of the significant relationships with contract duration or AS Total and its subfactors, however, doing so eliminated the significant relationship between depressive symptoms and dropout.

To examine the incremental validity of AS above and beyond other relevant variables, a logistic regression was conducted (Z-scored values were used for ease of comparing OR’s across continuous and categorical predictors). Level 1 included contract time, Level 2 included legal obligation, depressive symptoms, and alcohol frequency as covariates due to their significant relationship with either dropout or AS, and Level 3 included AS (see Table 2). The final model was significant (p < .001), and as hypothesized, AS provided significant incremental validity (OR = 1.54; p < .05). When additional regressions were conducted separately for each AS subfactor, AS Social was significant (OR = 1.61; p < .05, respectively), with AS Cognitive approaching significance (OR = 1.45; p = .055); AS physical was not significant (OR = 1.34; p = .142).

Table 2.

Summary of regression analysis examining the incremental validity of AS in the prediction of treatment dropout.

| df | F | B | SE | Wald | OR | CI’s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 1 | 19.684** | |||||

| Contract Duration | .736 | .169 | 18.854 | 2.087** | 1.497 – 2.913 | ||

| Level 2 | 4 | 25.006** | |||||

| Contract Duration | .522 | .209 | 6.278 | 1.686* | 1.120 – 2.538 | ||

| Legal Obligation | −.773 | .485 | 2.543 | 0.462 | 0.179 – 1.194 | ||

| Alcohol Frequency | −.116 | .186 | 0.393 | 0.890 | 0.619 – 1.281 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | .266 | .185 | 2.078 | 1.305 | 0.909 – 1.874 | ||

| Level 3 | 5 | 29.689** | |||||

| Contract Duration | .492 | .210 | 5.510 | 1.638* | 1.085 – 2.473 | ||

| Legal Obligation | −.967 | .502 | 3.706 | 0.380* | 0.142 – 1.018 | ||

| Alcohol Frequency | −.116 | .188 | 0.382 | 0.890 | 0.615 – 1.288 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | .182 | .192 | 0.900 | 1.200 | 0.823 – 1.748 | ||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .429 | .204 | 4.442 | 1.536* | 1.031 – 2.290 | ||

indicates p < .05;

indicates p < .01.

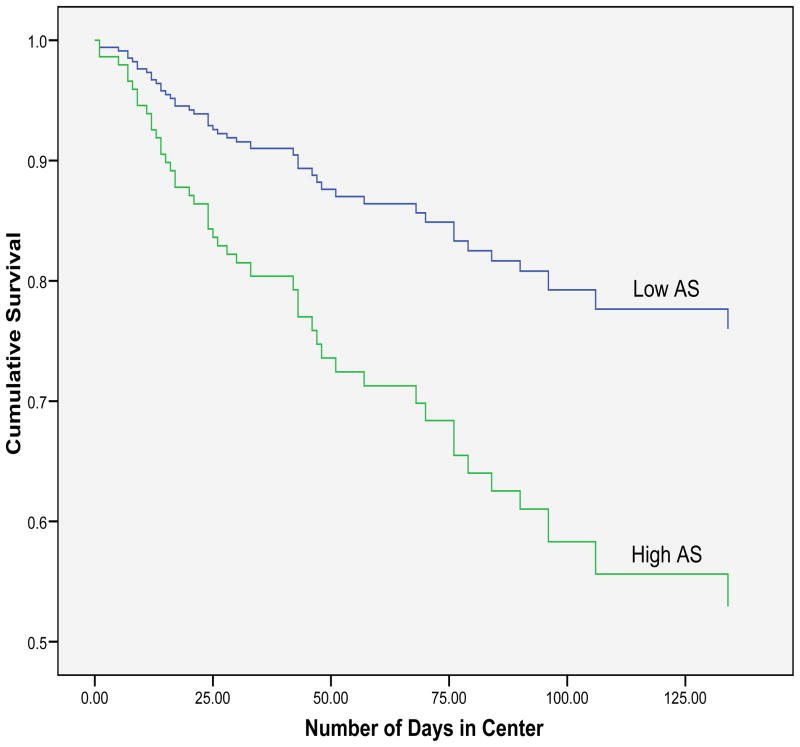

We also conducted a discrete-time survival analysis to predict days until dropout using Cox proportional hazards regression. Again controlling for contract duration, legal obligation, depressive symptoms, and alcohol frequency, AS provided incremental validity in a second step χ2 (1) = 6.23, p < .05, and the final model was significant, χ2 (5) = 14.48, p < .05, with AS score significantly related to treatment dropout, B = 0.38, SE = 0.15, Wald = 6.26, hazard ratio = 1.47, p = .012). To allow for visual presentation of this analysis, Figure 1 presents these results with AS dichotomized (Low AS ≤ 26; High AS > 26). When additional discrete-time survival analyses were conducted separately for each AS subfactor, AS Social was significant (OR = 1.61 < .01), with AS cognitive and physical both approaching significance (OR = 1.30 = .056; OR = 1.35 = .061).

Figure 1.

Discrete-time survival analysis to predict days until dropout using Cox proportional hazards regression as a function of low (≤ 26) or high score (> 26) on the Anxiety Sensitivity Index controlling key covariates.

Discussion

Although individuals seeking and enrolled in substance use treatment often do not complete treatment (Blanchard et al., 2003; Daley et al., 1998), little is known about the factors that govern such behavior. This study evaluated whether AS is uniquely related to an increased risk of dropout among consecutive admissions to a substance use residential treatment focusing on individuals dependent on heroin, crack/cocaine, or both. Consistent with prediction, AS was significantly elevated among those dropping out compared to those completing substance use treatment. Further analysis indicated AS also incrementally and prospectively predicted treatment dropout after controlling for the variance accounted for by the other theoretically and empirically-relevant factors of legal obligation and depressive symptoms, as well as alcohol use frequency. These findings suggest that the observed AS treatment-dropout effect is relatively unique and not attributable to shared variance with other relevant factors. In turn, this suggests that a hypersensitivity to noxious states, a core process implicit to the AS conceptual models (McNally, 2002), may be formative in shaping individual susceptibility to treatment dropout among drug users in residential treatment.

In addition to overall AS, we also examined the subfactors individually. Although findings were largely consistent, only AS Social was a significant predictor. This finding may be especially relevant to residential treatment such as that in the current study given the overarching lack of privacy in this type of setting (e.g., from open access dining to sleeping arrangements). That is, fears of the negative consequences of social presentation may be particularly relevant for understanding treatment dropout in this particular context. It may have been expected for the physical concerns lower-order factor to be related to dropout. The absence of this finding may be due in part to a unique feature of this setting. Specifically, the Center requires patients complete detoxification before entering. It may be that patients with physical AS concerns might self-select themselves out of treatment because they could not complete detoxification. In all cases, the present data highlight the need to better understand AS global and lower-order factors in regard to treatment dropout among individuals in residential and other therapeutic settings.

A number of questions emerge from the investigation. Perhaps foremost among these is isolating the mechanism by which AS is related to treatment dropout. Based upon previous work (Brown et al., 2001; Stewart et al., 1997) and conceptual models (Otto et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 1999), coping-oriented substance use motives may play a formative role. There is evidence to suggest AS increases the risk for adverse emotional experiences among drug using individuals in terms of withdrawal symptom profiles (Zvolensky et al., 2004) and anxiety-related symptoms (e.g., panic attacks; Zvolensky, Kotov, Antipova, & Schmidt, 2003). Extrapolating from such work, persons with heightened concern about the negative consequences of internal sensations may be more apt to use drugs in an effort to reduce distressing reactions and thereby discontinue treatment voluntarily or due to noncompliance. It would be advisable for future research to examine the linkages between AS, the specific motivational basis for drug use, and treatment dropout from residential clinics.

There also are a number of other interpretative caveats and directions for future research that deserve comment. First, despite the benefits of a prospective design, the present research design is limited nonetheless in terms of causal model hypothesis testing. Thus, it is unclear if AS is leading to higher rates of treatment dropout or whether some other characteristic or set of variables is contributing to both AS score and dropout. Although we examined a wide range of theoretically and empirically-relevant factors noted in past research on this topic, other factors not included such as frequency of life stressors or distress tolerance (Daughters et al., 2006) also may be playing a role in the interplay between AS and treatment dropout. It would be useful therefore for future work to expand the number and type of variables studied in relation to treatment dropout within a larger integrated theoretical framework. Second, the present sample was comprised of inner city African American patients who were court-ordered to residential treatment and dependent on heroin, crack/cocaine, or both. Thus, although our sample represents an important underserved group, it is unclear to what extent our results would generalize to participants with characteristics that differ across developmental (e.g., youth), ethnic (e.g., multiple ethnic groups of cultural backgrounds), legal (e.g., larger percentage of individuals seeking treatment with no legal obligation), and geographic domains (e.g., rural treatment settings), as well as other types of treatment settings (e.g., outpatient). Further, as discussed above the requirement that patients enter the Center after completing detoxification may have limited the robustness of the AS results, with specific relevance to the physical subscale. It is important for future work to assess patients in other types of setting where detoxification occurs as part of treatment and not as a prerequisite.

Third, the current study was underpowered to examine relationships across drug choice (i.e., heroin only defined as heroin dependent and not dependent on crack/cocaine, crack/cocaine only defined as crack/cocaine dependent and not dependent on heroin, and those dependent on both drugs) as a moderator of the effect between AS and treatment dropout, which would be relevant given previous work establishing a specific link between high AS and heroin dependent individuals with little to no crack/cocaine use (see Lejuez et al., 2006). Following from this work, it would be useful to investigate to what extent those with high AS who choose heroin and avoid crack/cocaine may be especially vulnerable to dropout. At a descriptive level, the current data provide some suggestive evidence. Specifically, among those who dropped out of the Center, AS was highest for heroin only (M = 35.7; SD = 14.6), lowest among those dependent on crack/cocaine only (M = 28.6; SD = 8.6), and in the middle for those dependent on both drugs M = 32.4; SD = 19.1); in contrast there was little difference among these groups for those completing treatment (heroin only M = 25.74, SD = 13.8; crack/cocaine only M = 26.0, SD = 10.9; Both M = 23.9; SD = 10.1). However, because of a modest number of individuals dependent only on heroin (20% of the total sample), there were simply too few dropouts from this group for statistical analyses. To address this important issue in future research, investigators should a priori plan to collect larger samples to allow for a sufficient number of heroin only and crack/cocaine only participants to determine if drug preference moderates the relationship between AS and dropout.

Fourth, although we controlled for several key variables including demographics, legal obligation, substance use frequency, and depressive symptoms, arguments could be made for utilizing several other key variables. In particular, studies have consistently demonstrated moderate correlations between AS and the personality dimensions of trait anxiety and neuroticism (Lilienfeld, 1999). Given that our measure of depressive symptoms (the CES-D) also has been found to be moderately to highly correlated with trait anxiety and neuroticism (Dunkley et al., 1997; Orme et al., 1986; Schroevers et al., 2000), it may be considered an adequate proxy for these personality traits in this early stage of research. However, because the CES-D does not capture all variance associated with trait anxiety and neuroticism, it is important for future studies to assess and control specifically for these personality traits in order to better establish the unique relationship between AS and relevant substance use outcomes.

Overall, the current study reflects an important, initial step in evaluating the role of AS in residential treatment dropout among drug dependent individuals. These data uniquely add to the growing theoretical (Morissette et al., 2007; Otto et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 1999; Tull et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2003) and empirical (Brown et al., 2001; Conrod et al., 1998; Zvolensky, Schmidt et al., 2005) literature linking AS to the nature of certain aspects of substance use problems. Moreover, the current findings provide a solid basis for future research in this area, including basic and clinical research focused on the role of AS in affective disturbances during the course of addictive drug use patterns and treatment outcome. In better understanding the mechanisms through which treatment dropout occurs, researchers could begin to devise integrated treatment protocols for certain drug use populations that address this cognitive vulnerability in order to enhance retention rates (e.g., see Tull, Schulzinger, Schmidt, Zvolensky, & Lejuez, 2007).

Footnotes

Other analyses were possible including limiting dropout just to the first 30 days (minimum contract across participants) or using percent of contract completed. Although both provide similar findings to dropout at any time controlling for contract duration as used throughout, the first is limited by a considerably smaller percentage of dropouts (14.8%) and the second by skew associated with 74.6% evidencing a percent completion of 100%. Finally, total number of days in the center is not appropriate as residents rarely could choose their contract length and could stay beyond the agreed length only under extreme circumstances.

Termination of treatment prior to the contract duration set at intake could occur for voluntary reasons or removal due to noncompliance, however, because findings were not differentially related to either type of treatment termination, both sets of individuals were collapsed into a single dropout group as has been done in previous work (Daughters et al., 2005).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

C.W. Lejuez, University of Maryland

Michael J. Zvolensky, University of Vermont

Stacey B. Daughters, University of Maryland

Marina A. Bornovalova, University of Maryland

Autumn Paulson, University of Maryland.

Matthew T. Tull, University of Maryland

Kenneth Ettinger, University of Maryland.

Michael W. Otto, Boston University

References

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM. Patient Factors Related to Early Attrition from an Outpatient Cocaine Research Clinic: A Preliminary Report. International Journal of the Addictions. 1991;26:327–334. doi: 10.3109/10826089109058888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, McKay JR, Mulvaney FD, McLellan AT. Prediction of Attrition from Day Hospital Treatment in Lower Socioeconomic Cocaine-Dependent Men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;40:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Bux DA. Motivational subtypes and continuous measures of readiness for change: Concurrent and predictive validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:56–65. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Marijuana use motives: Concurrent relations to frequency of past 30-day use and anxiety sensitivity among young adult marijuana smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:713–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE. Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:887–899. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce TJ, Spiegel DA, Gregg SF, Nuzzarello A. Predictors of alprazolam discontinuation with and without cognitive behavior therapy in panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1156–1160. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus RE, Kindleberger LR, Dugan MC. Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal study of substance abusers. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:403–408. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau N, Stewart SH, Loba P. The relations of trait anxiety, sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents’ motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:803–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Vassileva J. Differential sensitivity to alcohol reinforcement in groups of men at risk for distinct alcoholic syndromes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1998;22:585–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. The NEO Personality Inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Swinson RP, Shulman ID, Kuch K, Reichman JT. Gender effects and alcohol use in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993:413–416. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90099-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Salloum IM, Zuckoff A, Kirisci L. Increasing treatment compliance among outpatients with depression and cocaine dependence: Results of a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1611–1613. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress Tolerance as a Predictor of Early Treatment Dropout in a Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Blankstein KR, Flett GL. Specific cognitive-personality vulnerability styles in depression and the five-factor model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;23:1041–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Scales (EPS Adult) London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Zvolensky MJ, Stickle TR, Bonn-Miller MO, Leen-Feldner EW. Anxiety sensitivity – physical concerns as a moderator of the emotional consequences of emotion suppression during biological challenge: An experimental test using individual growth curve analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:249–272. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP) [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattenschwiler J, Ruesch P, Modestin J. Comparison of four groups of substance-abusing in-patients with different psychiatric comorbidity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandidavia. 2001;104:59–65. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge RM. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Zvolensky MJ, McLeish AC. The toxicity of anxiety sensitivity and worry as a function of emotion regulatory strategies. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Paulson A, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Zvolensky MJ. The Association between Heroin Use and Anxiety Sensitivity among Inner-City Individuals in Residential Drug Use Treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Anxiety sensitivity and the structure of personality. In: Taylor S, editor. Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research, and treatment of the fear of anxiety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- Maglione M, Chao B, Anglin D. Residential treatment of methamphetamine users: Correlates of dropout from the California Alcohol and Drug Data System (CADDS), 1994–1997. Addiction Research. 2000;8:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Bigelow C, Vickers-Lahti M, Spotts D. Planned duration of residential drug abuse treatment: Efficacy versus effectiveness. Addiction. 1997;92:1467–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlain RA, Cohen GH, Yoder J, Guidry L. Psychological test and demographic variables associated with retention of narcotic addicts in treatment. International Journal of the Addictions. 1977;12:399–410. doi: 10.3109/10826087709027230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:938–946. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Weisner CM. Predictors of substance abuse treatment retention among women and men in an HMO. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1525–1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Wish ED, Nemes S. Predictors of treatment outcomes in men and women admitted to a therapeutic community. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:207–227. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, and nicotine: A critical review of interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemes S, Wish ED, Messina N. Comparing the impact of standard and abbreviated treatment in a therapeutic community: Findings from the District of Columbia Treatment Initiative experiment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1999;17:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton GR. Substance use/abuse and anxiety sensitivity: what are the relationships? Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:935–46. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1986;42:28–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<28::aid-jclp2270420104>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Safren SA, Pollack MH. Internal cue exposure and the treatment of substance use disorders: Lessons from the treatment of panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Powers MB, Fischmann D. Emotional exposure in the treatment of substance use disorders: Conceptual model, evidence, and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:824–839. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA, Reiss S. Anxiety Sensitivity Index manual. 2. Worthington, OH: International Diagnostic Systems; 1992. Rev. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P. Psychopathology and substance abuse as predictors of program completion in a therapeutic community for drug abusers: A prospective study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1991;83:217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb05528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P. Psychopathology, treatment completion, and 5 years outcome: A prospective study of drug abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;15:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiger DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;21:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S. Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinical Psychology Review. 1991;11:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, McNally RJ. Expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR, editors. Theoretical Issues in Behavior Therapy. San Diego: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, DelaFuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-11. Addiction. 1993;88:791–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Richey JA, Cromer KR, Buckner JD. Discomfort intolerance: Evaluation of a potential risk factor for anxiety psychopathology. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Richey JA, Fitzpatrick KK. Discomfort intolerance: Development of a construct and measure relevant to panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:263–280. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroevers MJ, Sanderman R, van Sonderen E, Ranchor AV. The evaluation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale: Depressed and positive affect in cancer patients and healthy reference subjects. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9:1015–1029. doi: 10.1023/a:1016673003237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;11:294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Test manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Kushner MG. Introduction to the special issue on “Anxiety sensitivity and addictive behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:775–785. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Karp J, Pihl RO, Peterson RA. Anxiety sensitivity and self-reported reasons for drug use. Journal of Substance Use. 1997;9:223–240. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Samoluk SB, MacDonald AB. Anxiety sensitivity and substance use and abuse. In: Taylor S, editor. Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research, and treatment of the fear of anxiety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. The relations of anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and alexithymic coping to young adults’ motivations for drinking. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:274–296. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Peterson JB, Pihl RO. Anxiety sensitivity index scores predict self-reported alcohol consumption rates in university women. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies. DASIS Series: S-17, DHHS Publication No (SMA) 02-3727. Rockville, MD: 2002. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1992–2000. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, editor. Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research and treatment of the fear of anxiety. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tedlow JR, Fava M, Uebelacker LA, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF. Are study dropouts different from completers? Biological Psychiatry. 1996;40:668–670. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(96)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT. Expanding an anxiety sensitivity model of uncued panic attack frequency and symptom severity: The role of emotion dysregulation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Baruch D, Duplinsky M, Lejuez CW. Illicit drug use across the anxiety disorders: Prevalence, underlying mechanisms, and treatment. In: Zvolensky MJ, Smits JAJ, editors. Health behaviors and physical illness in anxiety and its disorders: Contemporary theory and research. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL. Further investigation of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depression: The role of experiential avoidance and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when distressed. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Schulzinger D, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW. Development and initial examination of a brief intervention for heightened anxiety sensitivity among heroin users. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:220–242. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg R, Barlow DH, Brown T. The hierarchical structure and general factor saturation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index: Evidence and implications. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:301–305. doi: 10.1177/0963721410388642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Forsyth JP. Anxiety sensitivity dimensions in the prediction of body vigilance and emotional avoidance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Baker KM, Leen-Feldner EW, Bonn-Miller MO, Feldner MT, Brown RA. Anxiety sensitivity: Association with intensity of retrospectively-rated smoking-related withdrawal symptoms and motivation to quit. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2004;33:114–125. doi: 10.1080/16506070310016969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Forsyth JP, Bernstein A, Leen-Feldner EW. A concurrent test of the anxiety sensitivity taxon: Its relation to bodily vigilance and perceptions of control over anxiety-related events in a sample of young adults. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2007;21:72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Kotov R, Antipova AV, Schmidt NB. Diathesis-stress model for panic-related distress: A test in a Russian epidemiological sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Kotov R, Antipova AV, Schmidt NB. Cross cultural evaluation of smokers risk for panic and anxiety pathology: A test in a Russian epidemiological sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:1199–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Kotov R, Antipova AV, Leen-Feldner E, Schmidt NB. Evaluating anxiety sensitivity, exposure to aversive life conditions, and problematic drinking in Russia: A test using an epidemiological sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:567–570. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, Antony MM, McCabe RE, Forsyth JP, Feldner MT, et al. Evaluating the role of panic disorder in emotional sensitivity processes involved with smoking. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:673–686. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, Stewart SH. Panic disorder and smoking. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:29–51. [Google Scholar]