Abstract

Numerous clinical studies have addressed the role of the natriuretic peptide system either as a diagnostic tool or as a guide to treatment in many cardiac diseases. The concept behind these studies has been that intravascular overload produces cardiac wall stress that alone stimulates the synthesis and release of natriuretic peptides the result of which is diuresis, natriuresis, and vasodilatation. However, almost thirty years after the discovery of the natriuretic peptides the measurement of these peptides, especially the BNP, has not met all the expectations of a simple and useful diagnostic tool in clinical cardiology, possibly due to confounding factors confusing the interpretation of the wall stress effect. In the same way as in pressure studies, it has been shown that hypoxia is a direct and sufficient stimulus for the synthesis and release of ANP and BNP. Additionally, hypoxia-response elements have been characterized from the promoter sequence of both the ANP and the BNP genes. Furthermore, a physiological rhythm (eupnea-apnea), causing changes in blood oxygen tension, regulates the plasma levels of ANP in sleeping seal pups which are spontaneously able to hold back their breathing. We suggest, on the basis of the extensive published literature, that the stimulus for the synthesis and release of natriuretic peptides is the oxygen gradient which always occurs in all human tissues in physiological conditions. The plasma volume contraction caused by natriuretic peptides (natriuresis, diuresis, and plasma shift) leads to hemoconcentration and ultimately to the increased oxygen-carrying capacity of unit volume of blood.

Keywords: Hypoxia, natriuretic peptides, hemoconcentration

Introduction

In 1981 Adolfo de Bold and colleagues [1] injected extracts of rat heart atrial tissue into the blood circulation of a rat and observed an increase in both natriuresis and diuresis, as well as a decrease in blood pressure. They concluded that the extracts contained a factor which produced these effects and gave it the name Atrial Natriuretic Factor (ANF). Many laboratories subsequently competed to be the first to reveal the structure of ANF, as a result of which several groups published its structure in mammals within a short period of time in 1983-84 [2-8]. The factor was a peptide (later referred to as Atrial Natriuretic Peptide, ANP) and as soon as the structure of the new hormone was known, it could be synthesized and a specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay could be developed [9,10], which facilitated experimentation. Within a few months, experiments were performed by infusing synthetic ANP into human volunteers. The responses were similar: blood pressure fell and diuresis and natriuresis increased [11]. ANP was localized in small granules near the nucleus of atrial myocytes, previously described by cell biologists [12,13], when the electron microscope had become available.

In 1985, when ANP was the main focus of interest in physiology, an extensive review was published on Natriuretic Hormone (NH), which had been studied for more than twenty years [14]. Its structure was not known, but unlike ANP, NH exerted its effects by inhibiting NaK-ATPase, thus probably being a digitalis-like substance. Later, an ouabain-like compound, qualitatively similar to commercial ouabain, was identified and characterized from human plasma [15].

These findings suggested that there was both an endogenous diuretic regulating primarily blood pressure and an endogenous digitalis affecting the heart muscle in the human body: thus, studies with ANP were directed towards clinical cardiology and possible drug development to treat high blood pressure. Also, during that period of time many departments of physiology working with whole animals were transformed into departments of molecular biology. Today, almost thirty years since the seminal findings, the biological significance of the natriuretic peptide system in healthy human adults of reproductive age appears to be still unclear despite over 24000 articles published on natriuretic peptides.

Here we present a hypothesis, based on our recent review [16], suggesting that the role of the natriuretic peptide system is to regulate hemoconcentration, thus offering a new interpretation of published clinical results and opening a new avenue for basic and clinical research.

All vertebrates have natriuretic peptides

Natriuretic peptides occur across the whole animal kingdom [17,18]. A-type natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptide (Brain Natriuretic Peptide, BNP) and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) are the three major types with their own receptors in peripheral tissues. Both ANP and BNP are stored in the heart as prohormones, which are processed in the sarcolemma into the biologically active carboxy-terminal hormones and into a more stable amino-terminal (NT) pro-sequence when released from myocytes into the circulation in response to a stimulus [19,20]. Recent findings, however, suggest that additional peripheral activation of circulating inactive precursors of natriuretic peptides occurs in circulation [21]. It appears that the C-type represents the ancestral form of natriuretic peptides as its variant is present in hagfish, the most ancient group of vertebrates which evolved about 500 million years ago, and which do not osmoregulate [22]. The wide distribution and structural versatility of natriuretic peptides within the animal kingdom support the notion that natriuretic peptides play a significant role in vertebrate physiology.

Oxygen availability in heart tissue

When studying the consumption of oxygen by the heart the majority of investigations have concentrated on the local and systemic mechanisms that regulate interactions between flow and anatomy to meet the oxygen need of the myocardium [23]. According to the prevailing concept, flow changes in coronary circulation are solely responsible for oxygen supply to the-myocardium, and error signals for the changes are metabolic factors other than oxygen tension in the heart [24]. In support of this concept, the augmented coronary flow can be as high as fivefold compared to control levels during heavy exercise suggesting that there is a large flow reserve in the contracting heart [24] and, specifically, that these flow changes will take place in both the large epicardial conduit and in resistance vessels [23]. Less attention has been paid to the diffusional component of oxygen supply from coronary arteries into myocytes and within myocytes. In all biological systems the oxygen gradient is from ca. 100 mmHg in the arterial capillaries, including coronary circulation, to close to 0 mmHg in the oxygen-consuming mitochondria. The steepness of the gradient as well as the extent of the low-oxygenated area in the tissue depends on the capillary density, blood flow, the amount of oxygen in the blood entering tissue capillaries, and the oxygen consumption of tissues. The resting heart undoubtedly receives an adequate amount of oxygen, but this is not necessarily true for the heart under strenuous exercise, for example, arterial oxygen saturation decreases in heavy exercise [25]. While perfusion via coronary flow enables normal cardiac function (i.e. myocardial contraction) [26], oxygen tensions in myocytes at different distances from the capillaries of coronary circulation are not known, largely because the measurements in situ are technically very difficult. In line with theoretical considerations, significant oxygen gradients have been shown to exist in both the myocardium [27] and the epicardium [28]. Notably, the cellular oxidative metabolism may be limited by diffusional oxygen transport from capillaries to mitochondria [27].

Hypoxia and the natriuretic peptide system

Accumulated experimental data clearly shows that a decrease in oxygen tension (hypoxia) is an independent factor regulating the synthesis and release of natriuretic peptides. Chronic hypoxic conditions lead to an increased synthesis of ANP in both the normal [29] and the hypertrophied myocardium [30-32]. When, in experimental animals with right ventricular hypertrophy, hypoxic conditions were replaced by normoxia, the ANP content fell to control levels despite persistent right ventricular hypertrophy [30]. These findings provide evidence that oxygen tension as such, and not the increase in heart mass alone, causes increased natriuretic peptide synthesis.

The transcription of natriuretic peptides in hypoxia is most likely mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) which transcriptionally regulate the expression of hundreds of hypoxia-dependent genes in all mammalian cell types [33]. In cultured atrial myocytes without any stretch changes, hypoxia stimulated the ANP gene expression and a 120-bp region of hypoxia-response elements could be characterized and localized within the ANP gene promoter [34]. Hypoxia-response elements have also been found in the promoter sequence of the human BNP gene [35-37], confirming that also the BNP gene is under the control of HIFs. Furthermore, in cell lines derived from human ventricular myocytes, hypoxia induced both the synthesis and secretion of BNP through HIF-dependent enhanced transcriptional activity [38].

The isolated perfused rodent heart is widely used to investigate a broad variety of questions both in cardiac physiology and pharmacology. Specifically, the perfusion system has been utilized to study the effects of volume/pressure overload on the release of natriuretic peptides since the 1980's. In the method called the Lan-gendorff preparation, the isolated heart is perfused in retrograde mode either under constant pressure or under constant flow conditions which can be manipulated. But when it comes to sufficient oxygenation, this model is problematic. Normally, crystalloid perfusion solutions contain only dissolved oxygen which carries maximally 1/30th of the amount carried by human blood in similar conditions, resulting most likely in inadequate oxygenation of the myocardium [39-43]. More precisely, about 20 % of the myocardium is hypoxic in buffer-perfused hearts even when they are perfused with fully oxygenated buffer solution [44]. In hypertrophied isolated hearts, perfused by the Langendorff method, ischemic areas developed although the perfusion solution was oxygen-saturated [45]. It seems, therefore, that in all the experiments on natriuretic peptides in which the Langendorff perfusion system has been used as a model, hypoxia should have been considered as a confounding factor when interpreting the results.

On the other hand, it was shown with the isolated Langendorff-perfused heart of rat and rabbit, in the same way as in pressure overload studies, that hypoxia was a direct and sufficient stimulus for the release of ANP: a short hypoxic exposure caused a several-fold increase of ANP concentration in the perfusate compared with control levels [46], while the ventricular pressure remained constant in these experiments. Later, these findings were corroborated with the same experimental model [47-49]. When the perfusion pressure was changed in this model, ANP release increased or decreased with concomitant changes in coronary flow rate [50]. Using perfused rat ventricle, it was shown that hypoxia stimulated the release of both ANP and BNP [51]. Although the experiments with Langendorff-perfused hearts of rats [52-54] and rabbits [55] were not designed to study the effects of oxygen as such, they clearly provided evidence that hypoxic conditions significantly increased the release of ANP into the perfusate. In line with these findings, hypoxia resulted in the release of ANP from the isolated heart atrium, pieces of the right ventricle, and isolated myocytes, in the absence of any mechanical load [56,57]. The source of ANP was later shown to be the atrial tissue both in neonatal [58] and in hypoxia-adapted rat hearts in vitro [59]. In muscle strips from human myocardium, in which any movements of actins and myosins were completely blocked with butanedione monoxime, resulting in a decrease in systolic force, hypoxia caused a significant increase in the transcription of the BNP gene [60].

Several in vivo studies support the findings and conclusions made with in vitro experimental models. In anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rabbits, while the mean arterial pressure, central venous pressure, and heart rate did not change significantly, an acute hypoxic stimulus increased plasma levels of ANP [61]. Similarly, an acute experimental exposure of man to hypoxia was associated with elevated concentration of plasma ANP [62-64], and in catheterized fetal sheep and bovine fetuses, with a reduced blood volume, hypoxia elevated plasma ANP [65-67]. Alveolar hypoxia further increased ANP concentrations three-fold in conscious lambs with a prior 15 % blood volume expansion [68]. When the blood flow was locally decreased in the pig heart by surgical interventions, the tissue content of BNP mRNA was increased several-fold in the wall area that had become hypoxic [69]. Chronic hypoxia alone, in the absence of cardiac dysfunction, was sufficient to cause an increase of ventricular BNP in neonatal swine [70].

Diving mammals such as seals, being able to spontaneously hold back their breathing (apnea) for long periods of time, are interesting physiological models from the point of view of this review. Apnea, which was associated with reduced oxygen tension in the blood, in sleeping seal pups caused elevated plasma levels of ANP which decreased to control levels when the pups breathed normally (eupnea) [71]. This is significant evidence that a physiological rhythm (eupnea-apnea), causing changes in oxygen tension, is able to regulate the plasma concentration of ANP. Table 1 gives examples of studies in which hypoxia has been shown to be associated with the natriuretic peptide system.

Table 1.

Experimental Evidence that Hypoxia Regulates Directly the Natriuretic Peptide System

| Model | References |

|---|---|

| Hypoxia-response elements in the promoter sequence of ANP and BNP genes | [34,35,36,37] |

| Isolated heart myocytes | [56,57,58,59] |

| Muscle strips from human myocardium, systolic force blocked | [60] |

| Langendorff-perfused rodent heart | [46,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Human subjects and whole animals | [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70] |

| Seal pups breathing normally | [71] |

Hypoxia in cardiac diseases

Patients with symptoms of heart failure have elevated BNP levels accurately identifying ventricular dysfunction. In those patients, who do not have heart failure but have only myocardial ischemia (stable coronary disease), plasma levels of BNP are associated with ischemia [72-75]. If patients had, additionally, left ventricular dysfunction, BNP independently predicted the presence of complex coronary lesions [76,77], while a recent meta-analysis suggested that the B-type natriuretic peptide was able to identify inducible myocardial ischemia as detected by standard non-invasive stress tests [78]. Again, ischemia is a direct and sufficient stimulus for natriuretic peptide release in coronary disease.

There are no direct measurements showing that hypoxic gradients occur in the hypertrophied human myocardium although hypoxic conditions will cause hypertrophy, resulting in augumented natriuretic peptide synthesis like in pulmonary hypertension. Since the wall thickness is increased in hypertrophy, a greater proportion of the myocardium will be below a given oxygen tension. However, there exists experimental evidence clearly showing that hypoxia alone is capable of regulating the plasma or tissue level of natriuretic peptides independent of vascular remodeling [29-32].

The measurement of natriuretic peptides, especially the BNP, seems not to have met all the requirements for a simple and useful tool in risk stratification in clinical cardiology [79]. Confusing data have accumulated, especially from critically ill patients in intensive care units [80], where patients most probably experience variable tissue oxygenation and, therefore, it has been speculated that the diagnostic performance of BNP and NT-proBNP to detect heart failure may be low in intensive care units [81], where the most promising indications seem to be hypoxic respiratory failure and the timing of extubation [82]. It is likely that in many cardiac diseases there are hypoxic gradients in the heart that play an independent role in regulating the synthesis of natriuretic peptides and in confusing the interpretation of the wall stress effect. It is of note that, when hypoxic conditions in experimental animals with right ventricular hypertrophy were replaced by normoxia, the ANP concentration fell to the control level, despite persistent right ventricular hypertrophy [30].

Hypoxia as a physiological stimulus for natriuretic peptides

Whenever vertebrates are exposed to hypoxia, they respond by an increase in the amount of hemoglobin per unit of blood volume. In acute hypoxia, plasma volume contracts as a result of diuresis and fluid shift from the circulation into the interstitial space and cells. While this decreases the total blood volume, it increases the oxygen carrying capacity of the unit blood volume by hemoconcentration [83,84,85,86] and, as a result, the overall oxygen transport will be enhanced. In addition, the total oxygen capacity of blood will be increased when erythrocytes are rapidly released into circulation from storage organs such as the spleen [87]. In chronic hypoxia, de novo synthesis of red blood cells, erythropoiesis, is increased, the fundamental stimulus being the ratio between the oxygen-consumed and the oxygen-delivered [88].

When ANP was infused into hypoxia-exposed subjects, about 10% of plasma volume was shifted into the interstitium, causing hemoconcentration which improved the pulmonary gas exchange in the subjects, while in normotensive subjects, an infusion of ANP caused plasma volume to decrease and vascular permeability to increase [89,90]. In nephrectomized rats, ANP caused an increase in hematocrit and a decrease in plasma volume [91]; this finding was later corroborated with normal rats exposed to alveolar hypoxia [92]. Both hypoxia [93] and ANP increased capillary permeability in experimental models [94,95]. When the effects of a low-dose infusion of ANP in normal men were investigated, the infusion, causing plasma ANP concentrations entirely within the range for normal subjects, was associated with significant urinary excretion [96]. The rapid volume decrease by diuresis, natriuresis, and water shift into the extracellular space has, however, been interpreted as ANP having a significant role in blood pressure regulation.

Anatomically the right atrium of heart is in contact with the blood before the respiratory surface. Thus, it will experience the full extent of the reduction in oxygen tension. Since the oxygen tension of incoming blood is much lower in the right atrium than in the left atrium, one would expect to find higher concentrations of ANP in the right atrium than in the left atrium and indeed this is the case in the laboratory rat [97]. Interestingly, ANP also affects the function of the body's major oxygen-sensing structure, the carotid body [98-101]. Stimulation of carotid chemoreceptors, as occurs in hypoxia, causes an increase of plasma ANP levels in dogs [102]. The short half-life and a large reservoir of ANP in the heart atria suggest that large amounts of ANP are needed for a relatively short period of time, thus fitting in with the hypoxia hypothesis. If the direct atrial stretch or pressure were the primary stimulus for the release of ANP as suggested by a rapid and large intravascular volume load in the rat [103], then the regulatory system should be able to differentiate a physiologically relevant signal from blood volume and flow changes in atria, caused by physical activity, without any information about the actual need for natriuretic peptides in peripheral tissues. In addition, atrial pressure swings are rather small, and atrial pressure is a result of complex and dynamic flows during the filling and emptying of atria [104]. It appears, therefore, that the signal-to-noise ratio of the direct atrial pressure hypothesis is low. Although commonly used in volume overload experiments, the laboratory rat originates from dry and warm environments where the rat hardly ever experiences large and rapid intravascular volume changes. Interestingly, a large volume overload did not increase the plasma ANP level in conscious rats, while it did so in anesthetized rats [105], and the brain has been unequivocally shown to have a trophical regulatory role in the volume-expansion-induced release of ANP from heart atria [106,107], with the activity of cardiac sympathetic nerves contributing to the regulation of ANP secretion [108].

Although it is clear that ANP relaxes precontracted rat aortic smooth muscle preparations in vitro, there appear to be both species and profound regional vascular differences in the vasodilatory activity of the natriuretic peptide [109-114], which may be due to the degree of contractile preload [115]. At systemic level, the hypotensive effects of ANP have been little studied: in anesthetized dogs, ANP decreased cardiac output independent of coronary vasoconstriction [116], which alone could result in hypotension. In contrast to the vasodilatation hypothesis, natriuretic peptide infusions caused gastrointestinal vasoconstriction in conscious dogs [117-121].

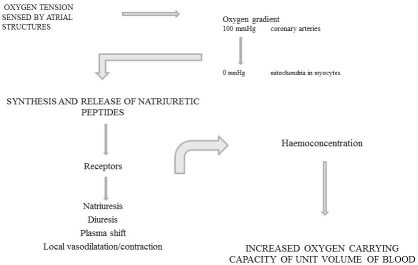

To conclude, we have outlined here, on the basis of a substantial amount of published experimental evidence, that hypoxic conditions directly stimulate the natriuretic peptide system under physiological circumstances. In hypoxia, mediated by natriuretic peptides, plasma volume contracts due to diuresis, natriuresis, and plasma shift, leading to hemoconcentration and, ultimately, to increased oxygen-carrying capacity per unit volume of blood (Figure 1). In many pathophysiological conditions, where natriuretic peptides have been used either as a diagnostic tool or as a guide to treatment, oxygen gradient has been an independent and confounding factor beyond the interpretation of the wall stress effect.

Figure 1.

The effects of oxygen gradient on the natriuretic peptide system. Atrial structures responsible for the regulation of the natriuretic peptide system sense oxygen tension. In the myocardium, wall stress modulates the oxygen gradient between coronary arteries (100 mmHg) and mitochondria (0 mmHg). The result is an increased synthesis and release of natriuretic peptides leading to haemoconcentration and to enhanced oxygen-carrying capacity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the funds from Academy of Finland, University of Turku, Finland..

References

- 1.de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extracts in rats. Life Sci. 1981;28:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn TG, de Bold ML, de Bold MJ. The amino acid sequence of an atrial peptide with potent diuretic and natriuretic properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;117:859–865. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas SA, Kleinert HD, Camargo MJ, Januszewicz A, Sealey JE, Laragh JH, Schilling JW, Lewicki JA, Johnson LK, Maack T. Purification, sequencing and synthesis of natriuretic and vasoactive rat atrial peptides. Nature. 1984;309:717–719. doi: 10.1038/309717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie MG, Geller DM, Cole BR, Siegel NR, Adams SP, Eubanks SR, Galluppi GR, Needleman P. Purification and sequence analysis of bioactive atrial peptides (Atriopeptins) Science. 1984;223:67–69. doi: 10.1126/science.6419347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kangawa K, Tawaragi Y, Oikawa S, Mizuno A, Sakuragawa Y, Nakazato H, Fukuda A, Minamino N, Matsuo H. Identification of rat gamma atrial natriuretic polypeptide and characterization of the cDNA encoding its precursor. Nature. 1984;312:152–154. doi: 10.1038/312152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misono KS, Fukumi H, Grammer RT, Inagami T. Rat Atrial Natriuretic Factor: Complete amino acid sequence and disulfide linkage essential for biological activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;119:524–529. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidah NG, Lazure C, Chrétien M, Thibault G, Garcia R, Cantin M, Genest J, Nutt RF, Brady SF, Lyle TA, Paleveda WJ, Colton CD, Ciccarone TM, Veber D. Amino acid sequence of homologous rat atrial peptides: Natriuretic activity of native and synthetic forms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2640–2644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seidman CE, Duby AD, Choi E, Graham RM, Haber E, Homcy C, Smith JA, Seidman JG. The structure of rat preproatrial natriuretic factor as defined by a complementary DNA clone. Science. 1984;224:324–326. doi: 10.1126/science.6234658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutkowska J, Thibault G, Januszewicz P, Cantin M, Genest J. Direct radioimmunoassay of atrial natriuretic factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakao K, Sugawara A, Morii N, Sakamoto M, Suda M, Soneda J, Ban T, Kihara M, Yamori Y, Shimokura M, Kiso Y, Imura H. Radioimmunoassay for alpha-human and rat atrial natriuretic polypeptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;124:815–821. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards AM, Ikram H, Yandle TG, Nicholls MG, Webster MW, Espiner EA. Renal, haemodynamic, and hormonal effects of human alpha atrial natriuretic peptide in healthy volunteers. Lancet. 1985;325:545–549. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisch B. A significant electron microscopic difference between the atria and the ventricles of the mammalian heart. Exp Med Surg. 1963;21:193–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson JD, Palade GE. Specific granules in atrial muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1964;23:151–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.23.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wardener WE, Clarkson EM. Concept of natriuretic hormone. Physiol Rev. 1985;65:658–759. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1985.65.3.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Bova S, DuCharme DW, Harris DW, Mandel F, Mathews WR, Ludens JH. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6259–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arjamaa O, Nikinmaa M. Review. Natriuretic peptides in hormonal regulation of hypoxia responses. Am J Physiol. 2009;296:R257–R264. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90696.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takei Y. Does the natriuretic peptide system exist throughout the animal and plant kingdom? J Comp Biochem Physiol B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;129:559–571. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toop T, Donald JA. Comparative aspects of natriuretic peptide physiology in nonmammalian vertebrates: a review. J Comp Physiol B: Biochem Systemic Environ Physiol. 2004;174:189–204. doi: 10.1007/s00360-003-0408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner DG, Songcang C, Glenn DJ, Grigsby CL. Molecular biology of the natriuretic peptide system. Implications for physiology and hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:419–426. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000258532.07418.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards AM. Natriuretic peptides: Update on peptide release, bioactivity, and clinical use. Hypertension. 2007;12:331–343. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.069153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clerico A, Giannoni A, Vittorini S, Passino C. Thirty years of the heart as an endocrine organ: Physiological role and clinical utility of cardiac natriuretic hormones. Am J Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00226.2011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KR, Olson KR. Comparative physiology of the piscine natriuretic peptide system. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;157:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schelbert HR. Anatomy and physiology of coronary blood flow. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s12350-010-9255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1009–1088. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dempsey JA, Wagner PD. Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1997–2006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaijser L, Grubbstrom J, Berglund B. Coronary circulation in acute hypoxia. Clin Physiol. 1990;10:259–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1990.tb00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi E, Doi K. Review. Impact of diffusional oxygen transport on oxidative metabolism in the heart. Jap J Physiol. 1998;48:243–252. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.48.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuurbier CJ, van Iterson M, Ince C. Review. Functional heterogeneity of oxygen supplyconsumption ratio in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:488–497. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00231-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winter RJ, Meleagros L, Pervez S, Jamal H, Krausz T, Polak JM, Bloom SR. Atrial natriuretic peptide levels in plasma and cardiac tissues after chronic hypoxia in rats. Clin Sci. 1989;76:95–101. doi: 10.1042/cs0760095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockmann PT, Will DH, Sides SD, Brunnert SR, Wilner GD, Leahy KM, Wiegand RD, Needleman P. Reversible induction of right ventricular atriopeptin synthesis in hypertrophy due to hypoxia. Circ Res. 1988;63:207–213. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie JC, Kelley KB, Merisko-Liversidge EM, Kennedy J, Klein RM. Developmental pattern of ventricular atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) expression in chronically hypoxic rats as an indicator of the hypertrophied process. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1994;26:1753–1767. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma S, Taegtmeyer H, Adrogue J, Razeghi P, Sen S, Ngumbela K, Essop MF. Dynamic changes of gene expression in hypoxiainduced right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H1185–H1192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00916.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahiri S, Roy A, Baby SM, Hoshi T, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing in the body. Progr Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;96:249–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chun YS, Hyun JY, Kwak YG, Kim IS, Kim CH, Choi E, Kim MS, Park JW. Hypoxic activation of the atrial natriuretic peptide gene promoter through direct and indirect actions of hypoxiainducible factor-1. Biochem J. 2003;370:149–157. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo Y, Jiang C, Belangor AJ, Akita GY, Wadsworth SC, Gregory RJ, Vincent KA. A constitutively active hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/VP16 hybrid factor activates expression of the human B-type natriuretic peptide gene. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1953–1962. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilhide ME, Jones WK. Potential therapeutic gene for the treatment of ischemic disease: Ad2/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1)/VP16 enhances B-type natriuretic peptide gene expression via a HIF-1-responsive element. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1773–1778. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weidemann A, Klanke B, Wagner M, Volk T, Willam C, Wiesener MS, Eckardt KU, Warnecke C. Hypoxia, via stimulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1α, is a direct and sufficient stimulus for brain-type natriuretic peptide induction. Biochem J. 2008;409:233–242. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casals G, Ros J, Sionis A, Davidson MM, Morales-Ruiz M, Jiménez W. Hypoxia induces B-type natriuretic peptide release in cell lines derived from human cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol. 2009;97:H550–H555. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00250.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edlund A, Wennmalm A. Oxygen consumption in rabbit Langendorff hearts perfused with saline medium. Acta Physiol Scand. 1981;113:117–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1981.tb06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hülsman WC, de Wit LEA. Acidosis, cardiac stunning and its prevention. Cell Biol Int Reports. 1990;14:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(90)91200-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murashita T, Kempsford RD, Hearse DJ. Oxygen supply and oxygen demand in the isolated working rabbit heart perfused with asanguinous crystalloid solution. Cardiovasc Res. 1991;25:198–206. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beard DA, Schenkman KA, Feigl EO. Myocardial oxygenation in isolated hearts predicted by an anatomically realistic microvascular transport model. Am J Physiol. 2003;283:H1826–H1836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00380.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schenkman KA, Beard DA, Ciesielski WA, Feigl EO. Comparison of buffer and red blood cell perfusion of guinea pig heart oxygenation. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:H1819–H1825. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00383.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ejike JC, Arakaki L, Beard DA, Ciesielski WA, Feigl EO, Schenkman KA. Myocardial oxygenation and adenosine release in isolated guinea pig hearts during changes in contractility. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H2062–H2067. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00777.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashruf JF, Ince C, Bruining HA. Regional ischemia in hypertrophied Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1999;46:H1532–H1539. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.4.H1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baertschi AJ, Hausmaninger C, Walsh RS, Mentzer RM, Jr, Wyatt DA, Pence RA. Hypoxiainduced release of atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) from the isolated rat and rabbit heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;140:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lew RA, Baertschi AJ. Mechanisms of hypoxiainduced atrial natriuretic factor release from rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H147–H156. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen BN, Rayner TE, Menadue MF, McLennan PL, Oliver JR. Effect of ischemia and role of eicosanoids in release of atrial natriuretic factor from rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1576–1579. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.9.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Oliver JR, Horowitz JD. The role of endothelin in mediating ischemia/hypoxiainduced atrial natriuretic peptide release. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43:227–233. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naruse M, Higashida T, Naruse K, Shibasaki T, Demura H, Ingami T, Shizume K. Coronary hemodynamics and cardiac beating modulate atrial natriuretic factor release from isolated Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. Life Sci. 1987;49:421–427. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toth M, Vuorinen KH, Vuolteenaho O, Hassinen IE, Uusimaa PA, Leppäluoto J, Ruskoaho H. Hypoxia stimulates release of ANP and BNP from perfused rat ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1572–H1580. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uusimaa PA, Peuhkurinen KJ, Hassinen IE, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H. 1992a. Ischemia stimulates the release of atrial natriuretic peptide from rat cardiac ventricular myocardium in vitro. Life Sci. 1992a;52:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90438-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uusimaa PA, Peuhkurinen KJ, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H, Hassinen IE. Role of myocardial redox and energy states in ischemiastimulated release of atrial natriuretic peptide. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992b;24:191–205. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93155-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arad M, Zamir N, Horowitz L, Oxman T, Rabinowit B. Release of atrial natriuretic peptide in brief ischemia-reperfused in isolated rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1971–H1978. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.5.H1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Focaccio A, Ambrosio G, Enea I, Russo R, Balestrieri P, Chiariello M, Volpe M. Influence of O2 deprivation, reduced flow, and temperature on release of ANP from rabbit hearts. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H2352–H2357. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.6.H2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ljusegren ME, Andersson RG. Hypoxia induces release of atrial natriuretic peptide in rat atrial tissue: a role for this peptide during low oxygen stress. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;350:189–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00241095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hopkins WE, Chen Z, Fukagawa NK, Hall C, Knot HJ, LeWinter MM. Increased atrial and brain natriuretic peptides in adults with cyanotic congential heart disease: enhanced understanding of the relationship between hypoxia and natriuretic peptide secretion. Circulation. 2004;109:2872–2877. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129305.25115.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klinger JR, Pietras L, Warburton R, Hill NS. Reduced oxygen tension increases atrial natriuretic peptide release from atrial cardiocytes. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:847–853. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Casserly B, Pietras L, Schuyler J, Wang R, Hill NS, Klinger JR. Cardiac atria are the primary source of ANP release in hypoxia-adapted rats. Life Sci. 2010;87:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Möllmann H, Nef HM, Kostin S, Dragu A, Maack C, Weber M, Troidi C, Rolf A, Elsässer A, Böhm M, Brantner R, Hamm CW, Holubarsch CJ. Ischemia triggers BNP expression in the human myocardium independent from mechanical stress. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baertschi AJ, Adams JM, Sullivan MP. Acute hypoxemia stimulates atrial natriuretic factor secretion in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H295–H300. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.2.H295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lawrence DL, Skatrud JB, Shenker Y. Effect of hypoxia on atrial natriuretic factor and aldosterone regulation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:E243–E438. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.2.E243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Angelis C, Ferri C, Urbani L, Farrac S. Effect of acute exposure to hypoxia on electrolytes and water metabolism regulatory hormones. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67:746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Due-Andersen R, Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Høi-Hansen N, Olsen NV, Kistorp C, Faber J, Boomsma F, Thorsteinsson B. NT-pro-BNP during hypoglycemia and hypoxemia in normal subjects: impact of renin-angiotensin system. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1080–1085. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01082.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheung CY, Brace RA. Fetal hypoxia elevates plasma atrial natriuretic factor concentration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:1263–1268. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson DD, Singh BM, Cheung CY. Effect of three hours of hypoxia on atrial natriuretic factor gene expression in the ovine fetal heart. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogunyemi DA, Koos BJ, Arora CP, Castro LC, Mason BA. Adenosine modulates hypoxiainduced atrial natriuretic peptide release in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H282–H287. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baertschi AJ, Teague WG. Alveolar hypoxia is a powerful stimulus for ANF release in conscious lambs. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H990–H998. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goetze JP, Gore A, Moller CH, Steinbruchel DA, Rehfeld JF, Nielsen LB. Acute myocardial hypoxia increases BNP gene expression. FASEB J. 2004;18:1928–1930. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1336fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khan AR, Birbach M, Cohen MS, Ittenbach RF, Spray TL, Levy RJ, Gaynor JW. Chronic hypoxemia increases ventricular brain natriuretic peptide precursors in neonatal swine. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zenteno-Savin T, Castellini MA. Changes in the plasma levels of vasoactive hormones during apnea in seals. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1998;119:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(97)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bibbins-Domingo K, Ansari M, Schiller NB, Massie B, Whooley MA. B-type natriuretic peptide and ischemia in patients with stable coronary disease: data from Heart and Soul study. Circulation. 2003;108:2987–2992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103681.04726.9C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goetze JP, Christoffersen C, Perko M, Arendrup H, Rehfeld JF, Kastrup J, Nielsen LB. Increased cardiac BNP expression associated with myocardial ischemia. FASEB J. 2003;17:1105–1107. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0796fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weber M, Dill T, Arnold R, Rau M, Ekinci O, Müller KD, Berkovitsch A, Mitrovic V, Hamm C. N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide predicts extent coronary artery disease and ischemia in patients with stable angina pectoris. Am Heart J. 2004;148:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Staub D, Jonas N, Zellweger MJ, Nusbaumer C, Wild D, Pfisterer ME, Müller-Brand J, Perruchoud AP, Müller C. Use of N-terminal pro-Btype natriuretic peptide to detect myocardial ischemia. Am J Med. 2005;118(1287):e9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Navarro Estrada JL, Rubinstein F, Bahit MC, Rolandi F, Perez de Arenaza D, Gabay JM, Alvarez J, Sarmiento R, Rojas Matas C, Sztejfman C, Tettamanzi A, de Miguel R, Guzman L. PACS Investigators. NT-probrain natriuretic peptide predicts complexity and severity of the coronary lesions in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1093.e1–1093.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolber T, Maeder M, Rickli H, Riesen W, Binggeli C, Duru F, Ammann P. N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide used for the prediction of coronary artery stenosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nadir MA, Witham DM, Szwejkowski BR, Struthers AD. Meta-analysis of B-type natriuretic peptide's ability to identify stress induced myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baibars M, Ibrahim A, Fang JC, Sipahi I. Editorial. Natriuretic peptide-guided management of patients with heart failure: a decade of progress but still a controversy. Future Cardiol. 2010;6:743–747. doi: 10.2217/fca.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Christenson RH. What is the value of B-type natriuretic peptide testing for diagnosis, prognosis or monitoring of critically ill adult patients in intensive care unit? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1524–1532. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Omland T. Advances in congestive heart failure management in the intensive care unit: Btype natriuretic peptides in evaluation of acute heart failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S17–S27. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000296266.74913.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Müller C, Maisel A, Mebazaa, Filippatos GS. The use of B-type natriuretic peptides in the intensive care units. Congest Heart Fail. 2008;14:43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nikinmaa M. Vertebrate red blood cells. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nikinmaa M. Membrane transport and the control of haemoglobin-oxygen affinity in nucleated erythrocytes. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:301–321. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Isbister JP. Physiology and pathophysiology of blood volume regulation. Transfus Sci. 1997;18:409–423. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3886(97)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nikinmaa M. Haemoglobin function in verte brates: evolutionary changes in cellular regulation in hypoxia. Respir Physiol. 2001;128:301–321. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nilsson S. Autonomic nerve function in the vertebrates. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grant WS, Root WS. Fundamental stimulus for erythropoiesis. Physiol Rev. 1952;42:449–498. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1952.32.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Westerndorp RG, Roos AN, van der Hoeven HG, Tjiong MY, Simons R, Frölich M, Souverijn JH, Meinders AE. Atrial natriuretic peptide improves pulmonary gas exchange in subjects exposed to hypoxia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:304–309. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wijeyaratne CN, Moult PJ. The effect of alpha human natriuretic peptide on plasma volume and vascular permeability in normotensive subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:343–346. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.2.8432776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Almeida FA, Suzuki M, Maack T. Atrial natriuretic factor increases hematocrit and decrease plasma volume in nephrectomized rats. Life Sci. 1986;39:1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Albert TS, Tucker VL, Renkin EM. Atrial natriuretic peptide levels and plasma volume contraction in acute alveolar hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:102–110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tucker VL, Huxley VH. O2 modulation of singlevessel hydraulic conductance. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H317–H323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.2.H317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huxley VH, Tucker VL, Verburg KM, Freeman RH. Increased capillary hydraulic conductivity induced by atrial natriuretic peptide. Circ Res. 1987;60:304–307. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huxley VH, Meyer DJ., Jr Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)-induced increase in capillary albumin and water flux. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;242:23–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8935-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Richards AM, McDonald D, Fizpatrik MA, Nicholls MG, Espiner EA, Ikram H, Jans S, Grant S, Yandle T. Atrial natriuretic hormone has biological effects in man at physiological plasma concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:1134–1139. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-6-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rinne A, Vuolteenaho O, Järvinen M, Dorn A, Arjamaa O. Atrial natriuretic polypeptides in the specific atrial granules of the rat heart: Immunohistochemical and radioimmunological quantification. Acta Histochem. 1986;80:19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(86)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang ZZ, He L, Stensaas LJ, Dinger BG, Fidone SJ. Localization and in vitro actions of atrial natriuretic peptide in the cat carotid body. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:942–946. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.2.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang WJ, He L, Chen J, Dinger D, Fidone S. Mechansims underlying chemoreceptor inhibition induced by atrial natriuretic peptide in rabbit carotid body. J Physiol. 1993;460:427–441. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.He L, Dinger B, Fidone S. Cellular mechanisms involved in carotid body inhibition produced by atrial natriuretic peptide. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:C845–C852. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Di Giulio C, Huang W, Waters V, Mkashi A, Bianchi G, Cacchio M, Macri MA, Lahiri S. Atrial natriuretic peptide stimulates cat carotid body chemoreceptors in vivo. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2003;134:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.al-Obaidi M, Whitaker EM, Karim F. The effect of discrete stimulation of carotid body chemoreceptors on atrial natriuretic peptide in anaesthetized dogs. J Physiol. 1991;443:519–531. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lang RE, Thölken H, Ganten D, Luft FC, Ruskoaho H, Unger T. Atrial natriuretic factor: a circulating hormone stimulated by volume loading. Nature. 1985;314:264–266. doi: 10.1038/314264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fyrenius A, Wigström L, Ebbers T, Karlsson M, Engvall J, Bolger AF. Three dimensional flow in the human left atrium. Heart. 2001;86:448–455. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sakata M, Greenwald JE, Needleman P. Paradoxical relationship between atriopeptin plasma levels and diuresis-natriuresis induced by acute volume expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3155–3159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Antunes-Rodrigues J, Ramalho MJ, Reis LC, Menani JV, Turrin MQ, Gutkowska J, McCann SM. Lesions of the hypothalamus and pituitary inhibit volume-expansion-induced release of atrial natriuretic peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2956–2960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gutkowska J, Antunes-Rodrigues J, McCann SM. Atrial natriuretic peptide in brain and pituitary gland. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:465–515. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiao JH, Baertschi AJ. Neural control of the endocrine heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7799–7803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Winquist RJ. The relaxant effects of atrial natriuretic factor on vascular smooth muscle. Life Sci. 1985;37:1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Winquist RJ. Possible mechanisms underlying the vasorelaxant response to atrial natriuretic factor. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2371–2375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Winquist RJ. Modulation of vascular tone by atrial natriuretic factor. Blood Vessels. 1987;24:128–131. doi: 10.1159/000158685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kawai Y, Ohhashi T. Heterogeneity in responses of isolated monkey arteries and veins to atrial natriuretic peptide. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1989;67:326–330. doi: 10.1139/y89-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shirai M, Ninomiya I, Shindo T. Selective and tone-dependent vasodilatation of arterial segment in rabbit and feline pulmonary microcirculation in response to ANP. Jpn J Physiol. 1993;43:485–99. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.43.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Endlich K, Steinhausen M. Natriuretic peptide receptors mediate different responses in rat renal microvessels. Kidney Int. 1997;52:202–207. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Winquist RJ, Hintze TH. Mechanisms of atrial natriuretic factor-induced vasodilatation. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90058-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Burnett JC, Jr, Rubanyi GM, Edwards BS, Schwab TR, Zimmermann RS, Vanhoutte PM. Atrial natriuretic peptide decreases cardiac output independently of coronary vasoconstriction. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1987;186:313–318. doi: 10.3181/00379727-186-42619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shen YT, Young MA, Ohanian RM, Vatner SF. Atrial natriuretic factor-induced systemic vasoconstriction in conscious dogs, rats, and monkeys. Circ Res. 1990;66:647–661. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.3.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Woods RL, Anderson WP. Atrial natriuretic peptide infusion causes vasoconstriction after autonomic blockade in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R813–R822. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.4.R813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shen YT, Graham RM, Vatner SF. Effects of atrial natriuretic factor on blood flow distribution and vascular resistance in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:H1893–H1902. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.6.H1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Woods RL, Smolich JJ. Regional blood flow effects of ANP in conscious dogs: preferential gastrointestinal vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1961–H1969. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Woods RL, Jones MJ. Atrial, B-type, and C-type natriuretic peptides cause mesenteric vasoconstriction in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1443–R1552. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]