Abstract

Skin permeability and local blood perfusion are important factors for transdermal drug delivery. Application of heat is expected to enhance microcirculation and local perfusion and/or blood vessel permeability, thus facilitating drug transfer to the systemic circulation. In addition, heating prior to or during topical application of a drug may facilitate skin penetration, increase kinetic energy, and facilitate drug absorption. The aim of the present study was to investigate skin vasomotor responses to mild heat generated by a controlled heat device on several body regions of healthy male and female subjects. Skin vasomotor responses in different body regions were recorded following different heat application paradigms (38, 41 and 43 °C, each for 15, 30, 60 sec). Test regions were forehead, forearm, dorsal hand, dorsal foot, and abdomen. Prior to and following the application of heat, local blood perfusion and skin temperature were measured by means of laser Doppler imaging (LDI) and thermography, respectively. It was found that a short-lasting heat application (43 °C for 60 sec) causes significant cutaneous hyperaemia (up to 2 folds increase in skin perfusion, and 5 °C increase in skin temperature) existing for up to 15 minutes. The site of application and sex did not influence the responses. The method was well tolerated without causing any pain or discomfort. These data suggest that controlled heat application is a simple, non-invasive method to significantly enhance local perfusion which may improve transcutaneous drug delivery.

Keywords: Vasomotor, cutaneous, perfusion, skin, temperature

Introduction

Delivery of drugs through the skin provides important advantages compared with oral and intravenous delivery routes. Transdermally delivered drugs avoid the risk and inconvenience of intravenous administration, bypass the liver first pass elimination, usually reduce chance of an overdose or underdose, allow easy termination, and permit both local and systemic effects [1, 2]. However, one should consider that transdermal absorption occurs through a slow process of diffusion driven by the gradient between the high concentration in the delivery system (e.g. a patch) and the zero concentration in the skin. Therefore, the delivery system must be kept in continuous contact with the skin for a considerable time (e.g. hours to days). The rate and amount of transdermal absorption depend on several factors, including the nature of the drug, the drug's concentration in the reservoir or matrix, and the area of skin covered by the patch [3].

Despite widespread interest in transdermal delivery, the mechanism underlying the transdermal absorption and kinetic factors that can influence the rate and amount of absorption is only partly understood [4, 5]. Absorption of drugs from cutaneous tissue depends on several factors, such as the quantity and composition of the tissue, capillary density, vascular permeability, and the rate of vascular perfusion [5, 6]. Studies have demonstrated that clearance of small diffusible molecules from dermis, particularly the upper dermis, is highly dependent on the local blood flow [7]. Hence, it is feasible to influence the absorption of drugs by applying local heat, which potentially can influence the above mentioned factors [8-11]. Several studies have demonstrated that absorption rate of transdermal and subcutaneous drugs are enhanced during heat exposure [12, 13]. Measurements have shown that not only the absorption rate, but also the total amount of drug absorbed and the plasma drug concentration afterwards are increased [11, 14]. Most likely, longer lasting heat can increase skin permeability, blood vessel permeability and also rate-limiting membrane permeability [8]. In addition, heat accelerates skin blood perfusion. This mechanism affects both drug passages through the skin and diffusion from cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue into the systemic circulation [8, 11]. The vasodilatory effect seen following application of local heat is extensive, and can potentially cause full local vasodilation. This response is mediated through a variety of mechanisms including neural and local mechanisms [9, 10]. Skin vasomotor responses in response to heat reflect in elevated local blood perfusion and skin temperature which have been measured with techniques such as Dop-pler probes for blood flow measurements and Infrared thermometry and telethermography for temperature measurements.

The differential responses of either sex or body regions to innocuous heat may result from differences in epidermal thickness, the innervation density of afferent fibers and microvascular network [15]. This may lead to variation of drug absorption via transcutaneous route. Hence, the aim of the present study was to apply local controlled heat on healthy human's skin in different regions of the body and to measure the subsequent vasomotor changes in females and males. This study utilized different local heating protocols (temperature/time), with a heat level below the usual heat pain threshold in adults [16].

Materials and methods

Subjects and study design

Twenty eight healthy volunteers (14 females, 14 males, 20-30 years) were recruited for this study through on-campus advertisements at Aalborg University, Denmark. Initial screening involved recording of demographic information and a review of medical history. The use of alcohol and caffeine, cold and hot drinks as well as smoking were prohibited. No subject had a past or present history of current systemic or skin diseases and none were taking any medication. Application of topical creams, lotions or cosmetics on the test sites was not allowed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (Counties of Nordjylland and Viborg, Denmark; case no. VN2005/62). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed at the research laboratories of Aalborg University, Denmark.

The study was designed in a way that the subjects were blinded to the selected temperature and duration of heat application. The site of the application was chosen in random. The subject relaxed on a comfortable bed at a supine position and exposed the test sites. There was a random rotation of the heat application with an adequate time interval between single heat applications. The measurement techniques for recording vasomotor changes were objective (laser Doppler scanning and thermography). All experiments were done in a quiet room with a constant temperature (23-24 °C). Subjects were asked to keep their eyes closed while wearing special goggles during laser scanning.

Body regions

Test regions were forehead, forearm, dorsal hand, dorsal foot, and abdomen. Both left and right sites were tested.

Heat application

The Medoc PATHWAY Pain & Sensory Evaluation System (Medoc Ltd. Advanced Medical Systems, Ramat Yishai, Israel) was used for controlled local heat application. The specific stimulation parameters were adjusted using the PATHWAY software (v. 4.4). The stimulation program was manually configured before initiation of the experiments. The applied parameters are summarized in Table 1. A 3.0 × 3.0 cm ATS thermode was utilized. The contact probe was attached to the skin by means of an elastic Velcro band.

Table 1.

Heat stimulation program configuration

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| Probe Type | ATS |

| Program Type | Ramp and Hold |

| Baseline (°C) | 32 |

| Trigger Configuration | Manual |

| Destination Temperature (°C) | 43 |

| Destination Rate (°C/sec) | 2 |

| Return Rate (°C/sec) | 1 |

Mild heat (38, 41, 43 °C) was delivered for short periods of time (15, 30, 60 sec). For repeated application, a similar paradigm was delivered every 5 min for 15 min followed by a gap of 15 minutes before the last stimulation. Baseline temperature of the thermode was adjusted to 32 °C and the heating rate toward the destination temperature was set to 2 °C/sec, to prevent a sensation of burning [17].

Laser Doppler Imaging (LDI)

Local skin perfusion was monitored using Laser Doppler Imaging (LDI). LDI is based on the Doppler principle, which is the shift in frequency of waves caused by movement of the reflecting object relative to the observer [18, 19]. This principle allows assessment of the movement of red blood cells in the most superficial skin layers (1-1.5 mm) [20, 21]. LDI generates a result in arbitrary units, whereby LDI can assess the blood flow in a certain area at a certain time point. The generated result reflects the blood flow at a proportional rate, allowing relative comparisons, for example changes in blood flow induced by local heating relative to a baseline or control measurement [9, 18].

Scanning was performed using a Moor Laser Doppler Imager (Moor Instruments, Devon, United Kingdom). In this study the scanner setup was adjusted using the parameters listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Configuration for LDI Scanning Parameters

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| Bandwidth (kHz) | 0.25 – 15 |

| Resolution (px) | 116 × 70 |

| Scan Area (cm × cm) | 6.0 × 6.0 |

| Scan Speed (ms/pixel) | 4 |

| Scan Distance (cm) | 30 |

The scanning area, called the region of interest (ROI), was defined as a 6.0 × 6.0 cm area, which allowed a safety margin around the 3.0 × 3.0 cm thermode, when applied in the center of the 6.0 × 6.0 cm area. The laser scanner was adjusted and calibrated to scan the ROI. Before and following every heat application, a laser scanning was performed. Laser scans were stored on computer's hard disk for off-line analysis of the profile and local changes of skin perfusion (moor LDI software (v. 5.3).

Thermography

Measurements of skin temperature were taken by means of thermography camera (FLIR Ther-moVision A40 M thermo camera, Sweden) at a distance of 50 cm from the tissue surface. The temperature resolution of the device was 0.08 °C. Thermographic images were stored on computer's hard disk for off-line analysis of the profile and local changes of average skin temperature within the area of the thermode (3.0 × 3.0 cm) (ThermaCAMTM Researcher Pro 2.8 SR-1). Before and following every heat application, thermo pictures were taken.

Safety

Any report for pain, irritation or discomfort was recorded in a safety profile sheet of the subjects.

Statistical analysis

All values in text and figures are presented as mean and standard errors of the mean (Mean±SEM). Data were analyzed with AN0VA for factors of temperature, time, body region and sex. Holm-Sidak Test was used as post hoc test where appropriate. The statistical evaluation was made by means of the SigmaPlot version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, US). P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

This test was designed and performed to investigate whether mild controlled local heat can induce vasomotor response in the skin. The response in terms of changes in skin perfusion and skin temperature were measured by LDI and thermography respectively. Overall, the application of mild heat (below pain threshold) provoked vasomotor reaction in all skin test regions (forehead, forearm, dorsal hand, dorsal foot, and abdomen) of females and males (n=28) without causing any pain or discomfort.

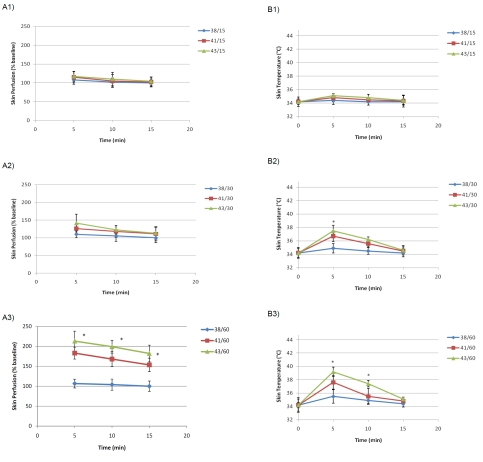

Our data indicated that the best (highest increase in laser Doppler response) combination paradigm (heat and time) was 43 °C for 60 sec that could significantly enhance skin perfusion and cutaneous temperature compared with other paradigms. The highest perfusion occurred within 5 min after heat application, revealed 2 folds increase in skin perfusion. The effect lasted for about 15 minutes after a single application. This phenomenon was not body region-, side- or sex-dependent (P>0.05) although abdomen region showed a higher tendency in females.

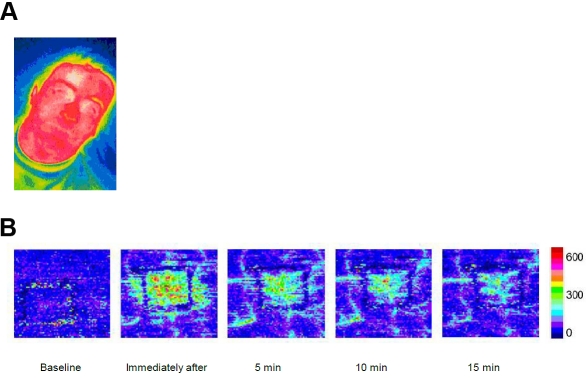

A typical thermographic picture and a laser image are shown in Figure 1. Skin perfusion (blood flow) and cutaneous temperature of forehead skin of healthy men and women are depicted in Figure 2A, B.

Figure 1.

Typical thermographic image (A) and laser Doppler scan (B) of the right forehead in a healthy male volunteer after application of mild heat (43°C for 60 sec).

Figure 2.

A.Skin Perfusion (% baseline) in the forehead skin of the subjects (n=28). Al: paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 15 sec; A2: paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 30 sec; A3. paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 60 sec. B. Skin Temperature (°C) in the forehead skin of the subjects (n=28). Bl: paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 15 sec; B2: paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 30 sec; B3: paradigm heat delivery of three different temperatures (38,41,43°C) for 60 sec. * indicates the difference from baseline (P<0.05).

The tested paradigms could be applicable for further studies in transcutaneous drug delivery of certain medications.

Application of vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

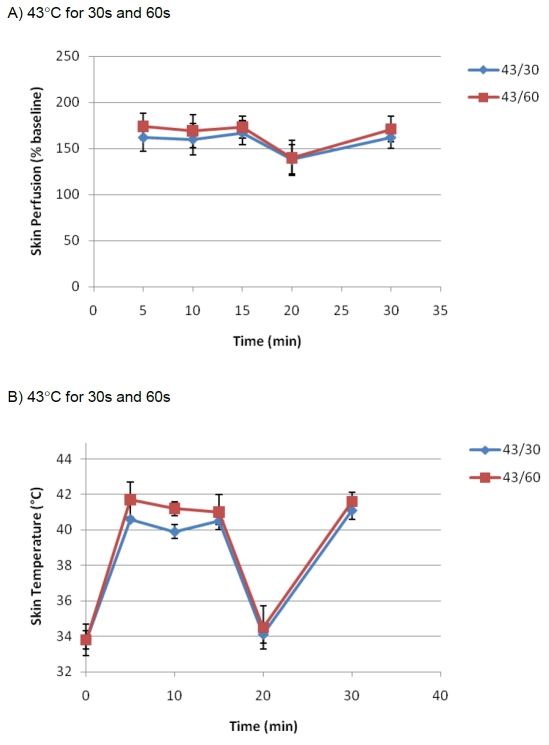

This test was designed and performed to investigate how the pattern of vasomotor responses would be following repeated mild heat application (43 °C for 30s and 43 °C for 60s). The test was performed on forearms of males (n=14).

Our data indicated that it is possible to maintain the vasomotor reaction at a constant level without significant changes over time (P>0.05). This phenomenon showed to be retainable even after a gap of no heat application. Data are shown in Figure 3A and B.

Figure 3.

The effect of the repeated mild heat application (43 °C for 30s and 43 °C for 60s) on skin per-fusion (A) and skin temperature (B) of the left forearm in healthy male volunteers (n=14). For repeated application, the heat was delivered every 5 min for 15 min followed by a gap of 15 minutes before the last stimulation.

The repeated mild heat paradigm could be applicable for further studies in transcutaneous drug delivery of certain medications.

Variations in vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

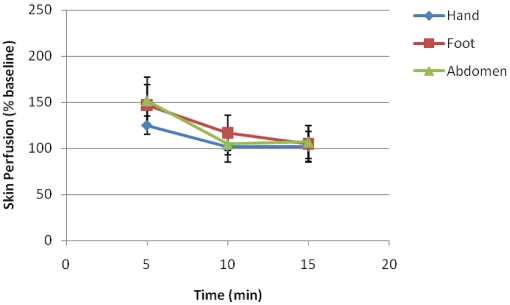

This test was designed and performed to investigate whether application of the best combination paradigm (43 °C for 60s) can vary in different body regions. The test was performed on foot, hand and abdomen of females and males (n=28) and skin perfusion data were pooled.

Our data indicated that overall body region did not cause a significant influence on skin perfusion applying this paradigm (Figure 4). However, one should consider that other paradigms may show variations to some extent.

Figure 4.

Skin Perfusion (% baseline) in the dorsum of the hand, dorsum of the foot and abdomen skin of the subjects (n=28).

Discussion

The present study utilized different local heating protocols to induce local peripheral vasomotor responses, which results in increased tissue perfusion and cutaneous temperature at different body sites.

Controlled local heating, induced a significant increase in skin perfusion, which is in agreement with previous findings [9, 11]. This may provide the basis for developing a standard method, which is capable of producing a stable and significant potentiating of skin perfusion to the drug application site whether it is applied topically (e.g. patches) or subcutaneously (absorption from depot).

Possible mechanisms underlying vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

Thermoregulation of the skin is complex and local vasomotor response to local heat may consist of three phases [9]. The initial response is mediated by an axon reflex, triggered by activation of cutaneous sensory fibers, which probably lasts for a few minutes. As heat is only applied transiently for 60 sec in the present study, this mechanism is thought to be involved. The nitric oxide synthase (NOS) system is mainly responsible for production of the vasodilatory response in the second phase, and produces a more stable response. It is more dependent on the inclination rate and temperature of the heat applied. Thus, it is likely that the NOS system was also involved in the vasodilatory response observed in the present study. However, the NOS system reacts slower as it is a local chemical process, which probably is not completely activated within one minute of heat application. Yet, continuous application of transient periods of heat, as in repeated protocol, may be sufficient to steadily activate NOS system, and thereby maintain a stable blood flow over time. If it is possible to trigger the NOS system with transient periods of heating, it could also be possible to activate the last component of the triphasic vasodilatory response. The third phase is accountable for an approximately 40% reduction in blood flow over time. Barcroft et al. [22] described this reduction in blood flow, which appeared after one hour for temperatures ranging from 37 °C to 42.5 °C. However, at 45 °C, blood flow remained stable throughout two hours. In the present study, 43 °C was transiently used, which is comparable with Barcroft et al. Nevertheless, only a minor decrease in blood flow was seen in the present study, and not as distinct as the decrease observed in the study conducted by Barcroft et al. Thus, the mechanisms involved in the third phase of the vasodilatory role are presumably neglectable in this study.

Application of vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

Enhanced drug absorption, through increased tissue perfusion, depends on the ability of a drug to diffuse across membrane of the vessels. Vasodilation at the drug administration site does not only increase the perfusion to the area where the drug is administered; it also increases the permeability of blood vessels to some extent, and thereby the surface area available for drug diffusion into the blood stream [6]. The extent, to which blood flow and the surface area available for diffusion can increase, depends on the several factors such as anatomy of the vessel plexus in the skin and also the duration of vasodilatory response. The microcirculation has been extensively reviewed by Braverman [23], who described the organization of non-glabrous cutaneous microcirculation in two plexus of arterioles: an upper horizontal plexus located in the papillary dermis just below the epidermis, and a lower horizontal plexus located in the deep dermis at the border of the underlying subcutaneous tissue. Applying heat increases the perfusion and permeability of both plexus, but due to the anatomy, there is probably more potential for heat-induced increased drug absorption into vessels of the upper plexus, as the total surface area of these vessels is larger. Therefore, heat presumably has more potential as an enhancer in drug delivery systems, where drugs are absorbed by vessels in the upper horizontal plexus, such as transdermal drug delivery.

Variations in vasodilatory response to local controlled heat

The microvascular blood system containes capillaries which vary due to several factors such as location, tissues being served, and metabolic needs of the tissues and organs [24]. Continuous capillaries are found mainly in the skin and muscle and in the current study we have most likely reached those capillaries in the skin in different body regions. The study finding did not indicate any significant difference between the tested regions. No difference between female and males was found. Although difficult to generalize this, but it seems that enhancement of blood flow within the range of heat application in the current study does not involve sex or region and may occur independent of such factors. Controlling factors are the time and the level of heat application. Hence, controlled heat could be applicable in drug delivery studies with desirable time course and stimulus parameters that can fit into the purpose of drug delivery. Theoretically, this will improve the therapeutic effect of drugs administered via skin. However, one should consider that tissue perfusion is not the only rate-limiting factor in the absorption of some drug molecules. The influence of heat on the rate of absorption should be further investigated for different drugs in order to validate controlled local heat application as a method in cutaneous drug delivery.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that application of mild heat (43 °C) for a short duration of time (60 sec) can enhance the local blood flow by up to 2 folds increase and skin temperature by up to 5 °C with no associated pain or discomfort. This effect lasts for 15 minutes following single application and can be retained following repeated application with minimum variations. The response is not site- or sex-dependent.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lydia A. Jakobsen, Anne Jensen, Lars E. Larsen, Morten R. Sørensen, Michael Trudslev, and Junzo Kamei for their assistance.

References

- 1.Roberts MS. Targeted drug delivery to the skin and deeper tissues: role of physiology, solute structure and disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:874–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R, Philip A. Modified Transdermal technologies: Breaking the barriers of drug permeation via the skin. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2007;6:633–644. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheindlin S. Transdermal drug delivery: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE. Mol Interv. 2004;4:308–312. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thong HY, Zhai H, Maibach HI. Percutaneous penetration enhancers: an overview. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;20:272–282. doi: 10.1159/000107575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster M, Bolzinger MA, Fessi H, Briancon S. Topical delivery of cosmetics and drugs. Molecular aspects of percutaneous absorption and delivery. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:309–323. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song CW. Effect of local hyperthermia on blood flow and microenvironment: a review. Cancer Res. 1984;44:4721s–4730s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh P, Roberts MS. Effects of vasocon-striction on dermal pharmacokinetics and local tissue distribution of compounds. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:783–791. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600830605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanakoski J, Seppala T. Heat exposure and drugs. A review of the effects of hyperthermia on pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;34:311–322. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JM, Kellogg DL., Jr Thermoregulatory and thermal control in the human cutaneous circulation. Front Biosci. 2010;2:825–853. doi: 10.2741/s105. (Schol Ed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minson CT, Berry LT, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1619–1626. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hull M. Heat-enhanced transdermal drug delivery: A survey paper. J Appl Res. 2002;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shomaker TS, Zhang J, Ashburn MA. Assessing the impact of heat on the systemic delivery of fentanyl through the transdermal fentanyl delivery system. Pain Med. 2000;1:225–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klemsdal TO, Gjesdal K, Bredesen JE. Heating and cooling of the nitroglycerin patch application area modify the plasma level of nitroglycerin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43:625–628. doi: 10.1007/BF02284961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry BW. Novel mechanisms and devices to enable successful transdermal drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;14:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandby-Moller J, Poulsen T, Wulf HC. Epidermal thickness at different body sites: relationship to age, gender, pigmentation, blood content, skin type and smoking habits. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:410–413. doi: 10.1080/00015550310015419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chery-Croze S. Painful sensation induced by a thermal cutaneous stimulus. Pain. 1983;17:109–137. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siekmann H. Recommended maximum temperatures for touchable surfaces. Appl Ergon. 1990;21:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(90)90076-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi CM, Bennett RG. Laser Dopplers to determine cutaneous blood flow. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:272–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eun HC. Evaluation of skin blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:337–347. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright CI, Kroner CI, Draijer R. Non-invasive methods and stimuli for evaluating the skin's microcirculation. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2006;54:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima A, Bakker J. Noninvasive monitoring of peripheral perfusion. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1316–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barcroft H, Edholm OG. The effect of temperature on blood flow and deep temperature in the human forearm. J Physiol. 1943;102:5–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1943.sp004009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braverman IM. The cutaneous microcirculation. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2000;5:3–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu AT, Miller RA. Natural Protein Toxins Affecting Cutaneous Microvascular Permeability. Journal of Toxicology-Toxin Reviews. 1992;11:193–239. [Google Scholar]