Abstract

Introduction

The principal objective of this study was to evaluate the incidence of adjacent-segment degeneration (ASD) in patients who underwent cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) as compared with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF).

Methods

It is a prospective cohort study of patients with a single-level cervical degenerative disc disease from C3 to C7 who underwent CDA or ACDF between January 2004 and December 2006, with a minimum follow-up of 3 years. The patients were evaluated pre- and postoperatively with the visual analog scale (VAS), the neck disability index (NDI), and a complete neurological examination. Plain radiographic assessments included sagittal-plane angulation, range of motion (ROM), and radiological signs of ASD.

Results

One hundred and five patients underwent ACDF and 85 were treated with CDA. The postoperative VAS and NDI were equivalent in both groups. The ROM was preserved in the CDA group but with a small decreased tendency within the time. Radiographic evidence of ASD was found in 11 (10.5%) patients in the ACDF group and in 7 (8.8%) subjects in the CDA group. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the ASD occurrence did not reach statistically significant differences (log rank, P = 0.72).

Conclusions

Preservation of motion in the CDA patients was not associated with a reduction of the incidence of symptomatic adjacent-segment disease and there may be other factors that influence ASD.

Keywords: Adjacent-segment degeneration, Degenerative disc disease, Cervical disc arthroplasty, Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion

Introduction

Degenerative cervical conditions with progressive neurological dysfunction and radiculopathy that are refractory to non-operative treatment modalities are the most common indications for surgery.

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is an effective treatment for central and paracentral disc herniations [1]. The goals of ACDF are to decompress the neural elements, to provide permanent segmental stabilization, to maintain the physiological lordosis and preserve the anatomical disc-space height.

In the untreated levels adjacent to a fusion, increased motion and elevated intradiscal pressures have been reported [2, 3]. Some investigators have postulated that these changes may lead to an increased risk of adjacent-segment degeneration (ASD) [4–6].

Cervical disc arthroplasty (CDA) has the potential of maintaining the physiological motion patterns following surgery. These characteristics may reduce or delay the onset of degenerative disc disease (DDD) at adjacent cervical spinal motion segments [7, 8].

A recent systematic review has stated that ASD has not been studied as a main outcome in any randomized clinical trial of patients having CDA surgery [9]. In the only report considered, level 2b evidence that investigated adjacent-level surgery rates, the results did not support a decrease in ASD in the CDA group as compared with the ACDF group [10].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the incidence of ASD in patients who underwent cervical arthroplasty and ACDF as the main outcome.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study of patients with cervical DDD who underwent CDA or ACDF between January 2004 and December 2006, with a minimum follow-up of 3 years.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients had to be older than 18 years of age, with single-level symptomatic DDD between C-3 and C-7 and intractable radiculopathy or/and myelopathy. Most patients reported a more than 6-week history of incapacitating neck and arm pain, unresponsive to non-surgical management such as physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory medication, and patients with a new neurologic deficit secondary to myelopathy. There was no specific criteria selection for CDA or ACDF surgery.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had evidence of cervical instability on dynamic flexion–extension radiographs, or sagittal-plane angulation greater than +20° at a single level. Other exclusion criteria were previous surgery at the involved level, severe cervical spondylosis consisting in disc-space narrowing, osteophytosis, loss of cervical lordosis, uncovertebral joint hypertrophy, apophyseal joint osteoarthritis, and diminished vertebral canal diameter, decreased bone density with a T score below −2.5 (defined as osteoporosis) measured by bone densitometry, or a medical condition that required long-term use of medication that could affect bone quality and fusion rates.

Lost-to-follow-up was considered when postoperative clinical evaluations were not successfully completed at 36 months, or because the inability to obtain an optimal radiographic technique (over- or under-penetration of the X-ray film, body habitus, shoulder overlay), or missing films.

Enrollment and preoperative work-up procedures

At the time of enrollment, the patients completed the following questionnaires: the visual analog scale (VAS) to measure arm pain intensity (0, no pain; 10, the worst pain) and the neck disability index (NDI) to quantify cervical pain and disability. The validated Spanish NDI version was applied [11]. In addition, a detailed neurological examination was performed and analgesic requirements, employment status, smoking frequency, and preexisting medical conditions were documented.

Surgery was performed by conventional technique [1]; in the ACDF group, we used the intersomatic cervical cages, cage® and LSK® cage with allograft bone. For cervical arthroplasty, the Discocerv® and Discover® devices were implanted [15].

Follow-up procedures

Follow-up evaluations were assessed at 6 weeks and at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 months post surgery, by one independent evaluator with a detailed neurological examination, and completed questionnaires of NDI and VAS.

Radiographic assessments: plain radiographic studies with consistent technical parameters were obtained at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 months after surgery. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs and dynamic flexion–extension lateral radiographs were obtained at each study point. Sagittal-plane angulation was measured on dynamic lateral radiographs using Cobb angle.

In patients with persistent, recurrent or new symptoms, a cervical MRI was obtained between 6 and 12 months after surgery.

The radiological evidence of adjacent-disc disease was determined by pre-established criteria as follows; new anterior osteophyte formation or enlargement of existing osteophytes, increased or new narrowing of a disc space (>30%), new or increased calcification of the anterior longitudinal ligament and the formation of radial osteophytes [16].

Statistical analysis

We employed descriptive statistics with measures of the central tendency and dispersion (±SD) in case of continuous variables and proportions and percentages in case of nominal variables. We employed parametric (t test) and non-parametric inferential statistic for nominal or ordinal variable (χ2). For survival analysis of ASD, the Kaplan–Meier was applied. SPSS statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used, and the level of significance was set at a probability value of less than 0.05.

Results

Of the 208 patients initially enrolled in the study, 190 reached the final follow-up interval (36 months) with complete clinical and radiological evaluations; 18 were excluded due to uncompleted studies. The final study group consisted of 105 patients who underwent ACDF and 85 subjects that were treated with CDA.

The mean age of patients in both groups was very similar: 46.5 years in the former and 46.9 years in the latter group. There were no gender differences; other demographic variables like tobacco and alcohol use and clinical as preoperative VAS and NDI were also homogeneous, Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information, comparing ACDF versus CDA

| Variable | ACDF | CDA | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 105 | 85 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 46.5 ± 6.4 | 46.9 ± 6.9 | 0.33 NS* |

| Sex | 45/60 | 29/51 | 0.36 NS** |

| Male/female | 42.9% | 36.3% | |

| Tobacco use (%) | 27 (25.7%) | 24 (39%) | 0.51 NS** |

| Alcohol use (%) | 20 (19) | 16 (20) | 0.87 NS** |

| VAS preop | 7.92 ± 0.9 | 7.95 ± 1.0 | 0.85 NS* |

| NDI preop | 41.41 ± 7.1 | 42.83 ± 6.8 | 0.17 NS* |

NS non-significant, VAS visual analog scale, NDI neck disability index

* t test; ** Two-sided χ2

Clinical features: the VAS to grade arm pain intensity was assessed at all postoperative periods and compared to the preoperative scores for both treated groups, no statistical differences were found between them. The initial postoperative VAS evaluation at 3 months (ACDF 2.95 ± 0.59 vs. CDA 3.01 ± 0.46, t test P = 0.3) and the final evaluation at 36 months (ACDF 2.99 ± 1.3 vs. CDA 3.2 ± 1.1, t test P = 0.5) were comparable.

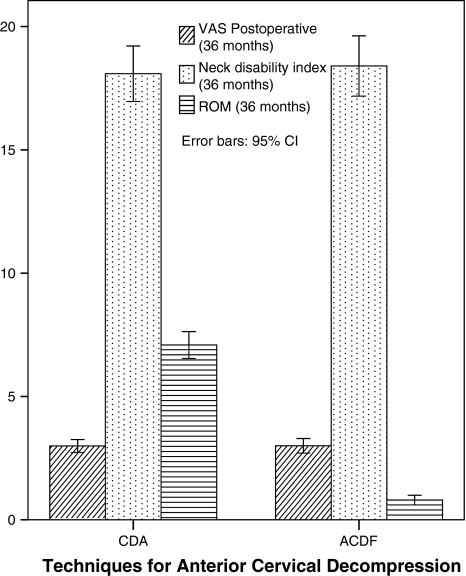

The NDI showed improvement from preoperative scores in both groups and was statistically equivalent at the 3-month follow-up evaluation (ACDF 13.0 ± 3.4 vs. CDA 13.5 ± 2.5, t test P = 0.2) and at the final 36-month assessment (ACDF 18.09 ± 5.8 vs. CDA 18.4 ± 5.4, t test P = 0.5), Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Bar graph final comparative the VAS, NDI and ROM between ACDF and CDA groups. Note similar results except on the ROM variable

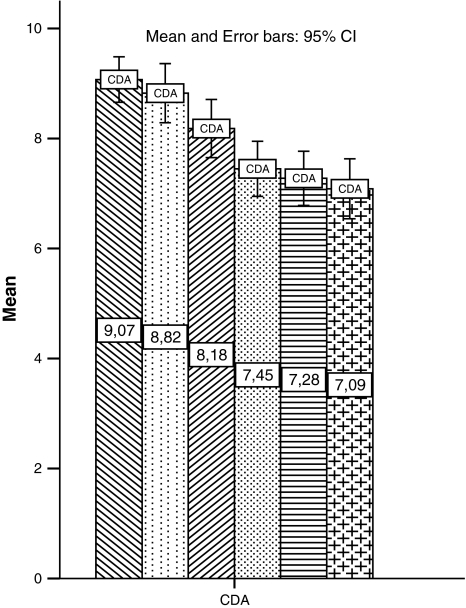

Radiographic assessments: the mean preoperative ROM at the treated level was 9.44° and 8.82º at 3 months after the surgery for the CDA group, with a small decreased tendency in the postoperative follow-up period, Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Bar graph shows the follow-up of ROM on patients who underwent CDA, from the preoperative phase until 36 months of follow-up. Note a small decrease tendency on the ROM with the time

Radiographic evidence of adjacent-segment degeneration was found in 11/105 (10.5%) patients in the ACDF group and in 7/85 (8.8%) subjects in the CDA group; no statistically significant difference was obtained (χ2, P = 0.69). Specifically, new anterior osteophyte formation was present in four patients in the ACDF group and in three subjects in the CDA group. Nine patients with ACDF and five with CDA had an increased or a new narrowing of the disc space >30%.

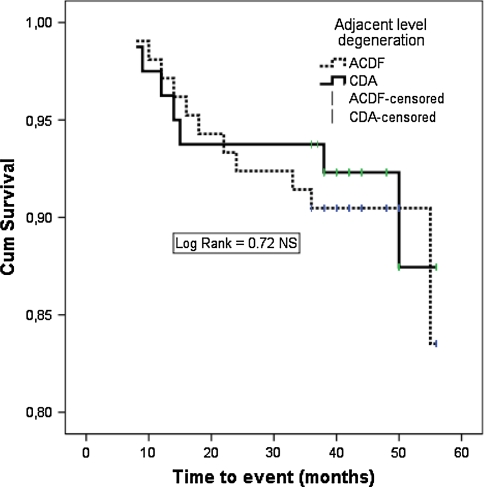

The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the occurrence of ASD event until the final follow-up, comparing ACDF and CDA did not reach statistically significant differences (log rank, P = 0.72), Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis graph, for ASD as the event of interest, comparing ACDF versus CDA. There was no statistically significant difference (log rank, P = 0.72)

Discussion

The concern that spinal fusion surgery may be a contributing factor to accelerated DDD has spurred an interest in motion preservation surgery.

ACDF has provided a high rate of clinical success for the cervical DDD; nevertheless, ASD has been reported as a complication secondary to the rigid fixation at the adjacent level. Hilibrand et al. [5, 6] reported ASD in approximately 25% of patients with single-level ACDFs 10 years after the initial procedure.

The theoretical advantage of cervical motion-sparing arthroplasty is the reduction in adjacent-level stresses, which may lead to a decreased risk of ASD; however, there is no randomized clinical trial that has investigated ASD as a main outcome [9].

European and Australian clinical trials of artificial cervical disc only described the clinical outcomes with cervical arthroplasty using validated measurements such as the NDI, the arm pain intensity VAS, and the neurological status [12–14].

The multicentric Bryan study published outcomes for the NDI, SF-36, numerical rating scales for neck and arm pain, angular range of motion, and the adverse occurrences in both techniques. The rates of fusion and secondary surgical procedures were also reported, but ASD incidence was not specifically studied [15].

Mummaneni et al. [10] described the rates for surgery on the adjacent level to fusion, but not precisely ASD as a main outcome. A recent systematic review suggests that this evidence is considered level 2b and does not support a decrease of ASD in patients who undergo CDA [9].

In this prospective observational study, with relatively comparable groups and a minimum of 36 months’ follow-up, ASD was the specific main outcome variable to evaluate. In the CDA group, the ROM was less affected, but it had small tendency to decrease within time, and in some cases, fusion was detected. In our experience, this preservation of motion in the CDA patients was not sufficient to reduce the incidence of symptomatic adjacent-segment disease.

One limitation of this report is the lack of randomization for any observational design that can mislead for selection bias; nevertheless, both comparative groups were homogeneous in demographic, co-morbidity, and preoperative symptoms. The other default is the absence of a validated and quantitative measurement for ASD; in this report, a previously published criterion for ASD was employed; however, a unified measurement is still needed [16].

There may be other factors that influence ASD occurrence besides motion preservation. A central question relates not only to the incidence of ASD, but also to its occurrence directly attributable to a previously performed fusion compared with the natural history of cervical disc degeneration [17].

Hilibrand also recognized that symptomatic ASD could be the result of a progressive cervical spondylosis at adjacent levels and not caused by the arthrodesis itself [17].

The role of cervical arthroplasty preventing ASD will remain unclear until level I evidence is obtained; meanwhile, there is no definitive evidence favoring arthroplasty over fusion.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bohlman HH, Emery SE, Goodfellow DB, Jones PK. Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. Long-term follow-up of one hundred and twenty-two patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1298–1307. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eck JC, Humphreys SC, Lim TH, Jeong ST, Kim JG, Hodges SD, et al. Biomechanical study on the effect of cervical spine fusion on adjacent level intradiscal pressure and segmental motion. Spine. 2002;27:2431–2434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsunaga S, Kabayama S, Yamamoto T, Yone K, Sakou T, Nakanishi K. Strain on intervertebral discs after anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Spine. 1999;24:670–675. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartolomei JC, Theodore N, Sonntag VK. Adjacent level degeneration after anterior cervical fusion: a clinical review. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2005;16:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilibrand AS, Yoo JU, Carlson GD, Bohlman HH. The success of anterior cervical arthrodesis adjacent to a previous fusion. Spine. 1997;22:1574–1579. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199707150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo M, Jones PK, Bohlman HH. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:519–528. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wigfield CC, Gill S, Nelson R, Langdon I, Metcalf N, Robertson J. Influence of an artificial cervical joint compared with fusion on adjacent-level motion in the treatment of degenerative cervical disc disease. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(1 Suppl):17–21. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.1.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiAngelo DJ, Roberston JT, Metcalf NH, McVay BJ, Davis RC. Biomechanical testing of an artificial cervical joint and an anterior cervical plate. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:314–323. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botelho R, Moraes OJ, Fernandes GA. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effect of cervical disc arthroplasty on reducing adjacent level degeneration. A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:6. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mummaneni PV, Burkus JK, Haid RW, Traynelis VC, Zdeblick TA. Clinical and radiographic analysis of cervical disc arthroplasty compared with allograft fusion: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:198–209. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacs FM, Bagó J, Royuela A, Seco J, Giménez S, Muriel A, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of instruments to measure neck pain disability. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummins BH, Robertson JT, Gill SS. Surgical experience with an implanted artificial cervical joint. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:943–948. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.6.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffin J, Calenbergh F, Loon J, Casey A, Kehr P, Liebig K, et al. Intermediate follow-up after treatment of degenerative disc disease by the Bryan Cervical Disc Prosthesis: single-level and bi-level. Spine. 2003;28:2673–2678. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000099392.90849.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekhon L. Cervical arthroplasty in the management of spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:307–313. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papadopoulos SM, Anderson PA, Fessler RG, Hacker RJ, et al. Comparison of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical decompression and fusion: clinical and radiographic results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Spine. 2009;34:101–107. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ee263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson JT, Papadopoulos SM, Traynelis VC. Assessment of adjacent-segment disease in patients treated with cervical fusion or arthroplasty: a prospective 2-year study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:417–423. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.6.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCormick PC. The adjacent segment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:1–4. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]