Abstract

Single-stage posterior corpectomy for the management of spinal tumors has been well described. Anterior column reconstruction has been accomplished using polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) or expandable cages (EC). The aim of this retrospective study was to compare PMMA versus ECs in anterior vertebral column reconstruction after posterior corpectomy for tumors in the lumbar and thoracolumbar spine. Between 2006 and 2009 we identified 32 patients that underwent a single-stage posterior extracavitary tumor resection and anterior reconstruction, 16 with PMMA and 16 with EC. There were no baseline differences in regards to age (mean: 58.2 years) or performance status. Differences between groups in terms of survival, estimated blood loss (EBL), kyphosis reduction (decrease in Cobb’s angle), pain, functional outcomes, and performance status were evaluated. Mean overall survival and EBL were 17 months and 1165 ml, respectively. No differences were noted between the study groups in regards to survival (p = 0.5) or EBL (p = 0.8). There was a trend for better Kyphosis reduction in favor of the EC group (10.04 vs. 5.45, p = 0.16). No difference in performance status or VAS improvements was observed (p > 0.05). Seven patients had complications that led to reoperation (5 infections). PMMA or ECs are viable options for reconstruction of the anterior vertebral column following tumor resection and corpectomy. Both approaches allow for correction of the kyphotic deformity, and stabilization of the anterior vertebral column with similar functional and performance status outcomes in the lumbar and thoracolumbar area.

Keywords: Spine metastasis, Polymethylmethacrylate, Expandable cage, Posterolateral approach

Introduction

The treatment for metastatic spine tumors is mainly palliative and the goals of treatment are to improve the patient’s quality of life, maintain or improve neurological function, and relieve pain. Indications for surgery include high-grade extradural spinal cord compression with relatively radioresistant metastases, tumor progression following radiation therapy, or spinal instability [1].

Patients with metastatic spine tumors often have multicolumn involvement and high-grade epidural compression, requiring circumferential decompression, and instrumentation.

Combined 360° approaches provide access to both the anterior and posterior elements simultaneously, but have the risk of devastating intraoperative complications, including increased blood loss, prolonged operative time and exacerbation of preexisting co-morbidities, principally of the respiratory system [2–5].

Single-stage posterolateral approaches for corpectomy and reconstruction of the vertebral body in metastatic thoraco-lumbar tumors have been well described [2, 6–8]. These approaches allow not only circumferential tumor resection but also simultaneous posterior instrumentation. Posterior segmental fixation is typically applied with four points of fixation superior and inferior to the level of decompression [9–11]. Anterior reconstruction can be done using an expandable cage (EC) or polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and pins. To the best of our knowledge there have been no previous studies directly comparing these two techniques.

In this study, we compared PMMA versus EC in anterior vertebral column reconstruction after posterior corpectomy in the thoracic and lumbar spine. We hypothesized that there is no difference in regards to survival, estimated blood loss (EBL), Kyphosis correction, neurological and functional outcome, and morbidity.

Surgical technique

The corpectomy and reconstruction of the anterior and posterior columns were performed through a standard single posterior transpedicular approach [1, 12]. All cases were monitored by somatosensory (SSEP) and motor evoked potentials (MEP) during surgery. If PMMA-pins are to be used, we first insert 2–4 Steinmann pins in the above and below vertebrae. Correct placement of the pins is verified with fluoroscopy, prior to cement application, since it is very difficult to remove them after it polymerizes. Meticulous cleaning of the endplates is important, to avoid cement compression against disk material which may eventually lead to loosening. Distraction is performed through the pedicle screws or alternatively with lamina spreader and cement is delivered into the corpectomy defect using a cement delivery device (e.g., cement gun) or a 50 cc syringe. Continuous irrigation is used to avoid thermal injury and continuous shaping of the cement is being performed with a number three Penfield, so as to have a clear plane between the cement and the dural sac, since the cement expands as polymerization occurs. When cement hardens, we carefully check if there is mobility of the cement fragment; further compression from the posterior screw-rod construct will ensure longevity of the hardware. If the cement is felt to be loose, it is removed with a high speed drill and new cement is placed until a satisfactory construct is achieved. If ECs are to be used, they are packed with bone graft and inserted horizontally and then rotated vertically into position to avoid sacrificing nerve roots as described by other authorities [8, 12]. If satisfactory position is confirmed by fluoroscopy, the cage is expanded in situ until a tight fit is achieved. Further compression by the posterior construct is also performed.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective review of our prospectively acquired database of all patients with thoracic or lumbar spinal metastasis who underwent tumor resection and immediate spinal column reconstruction through a transpedicular/costotransversectomy approach between 2006 and 2009 at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Institute by the senior author. A total of 85 consecutive patients with thoracic and lumbar spine metastases were identified. The indication for surgery was three-column spine disease, spinal instability, and/or progression of tumor following prior radiation therapy (six cases received preoperative radiation therapy). Exclusion criteria included previous history of spine surgery, brain metastasis, thoracic tumors (above T10), and follow-up less than 1 year. The rationale for excluding thoracic metastatic tumors was that typically nerve roots are sacrificed making reconstruction easier; additionally, by including patients with longer follow-up would potentially reveal more hardware failures. Thirty-two patients in lumbar and thoracolumbar junction (T10-L2) met the inclusion criteria and formed the basis of this study. Anterior reconstruction was performed using PMMA in 16 patients and an EC in 16 patients.

The mean age at presentation was 58.2 years (range 29–70 years), the mean age of the EC group was 56.3 years versus 60.1 years for the PMMA group (p = 0.23). The two groups were also comparable in terms of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) (mean value was 2.5 in both groups) and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) (62.5 vs 61.2, p = 0.8). The male/female ratio was 1.46 (19 males and 13 females), 1.3 in EC vs. 1.5 in PMMA group (p = 0.3). All tumors were high-grade metastatic malignancies. The most common histological types were renal cell and lung cancer. Patient demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients demographics

| No | Age | Sex | Tumor type | Level | Reconstruction | ASIA | KPS | ECOG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52 | M | Colon Cancer | T11 | PMMA | D | 80 | 2 |

| 2 | 34 | F | Endometrial | L4 | PMMA | E | 90 | 0 |

| 3 | 56 | F | Melanoma | T11 | Cage | E | 80 | 1 |

| 4 | 60 | M | Sarcoma | T11 | Cage | E | 80 | 1 |

| 5 | 62 | M | Melanoma | T11 | PMMA | C | 40 | 4 |

| 6 | 57 | F | Renal Cell | L1 | Cage | E | 80 | 2 |

| 7 | 63 | M | Colon | L2 | Cage | E | 80 | 1 |

| 8 | 48 | M | Lung | L1 | Cage | D | 60 | 4 |

| 9 | 66 | F | Melanoma | L3 | PMMA | C | 50 | 4 |

| 10 | 57 | M | Lung | L4 | Cage | D | 60 | 4 |

| 11 | 58 | M | Renal Cell | T12 | PMMA | D | 60 | 3 |

| 12 | 53 | M | Colon | L3 | Cage | C | 40 | 4 |

| 13 | 57 | M | Renal Cell | L2 | Cage | C | 50 | 4 |

| 14 | 62 | M | Thyroid | L4 | Cage | D | 60 | 2 |

| 15 | 29 | F | Sarcoma | T11, 12 | Cage | E | 80 | 1 |

| 16 | 56 | F | Renal Cell | T10, T11 | PMMA | C | 50 | 4 |

| 17 | 70 | F | Melanoma | L3 | PMMA | E | 80 | 1 |

| 18 | 69 | M | Lung | L2 | PMMA | D | 60 | 2 |

| 19 | 54 | M | Renal Cell | L1, L2 | Cage | C | 50 | 4 |

| 20 | 63 | M | Endometrial | L1, L2 | PMMA | E | 70 | 1 |

| 21 | 65 | F | Breast | T12 | PMMA | D | 60 | 2 |

| 22 | 60 | M | Renal Cell | T12 | Cage | C | 50 | 4 |

| 23 | 63 | M | Sarcoma | L1 | PMMA | D | 50 | 3 |

| 24 | 62 | F | Thyroid | T11, T12 | PMMA | C | 50 | 4 |

| 25 | 64 | M | Sarcoma | L2 | Cage | E | 70 | 0 |

| 26 | 48 | F | Melanoma | T10, 11 | PMMA | C | 40 | 4 |

| 27 | 64 | F | Colon | L1 | Cage | D | 50 | 3 |

| 28 | 66 | M | Sarcoma | T12 | Cage | E | 70 | 1 |

| 29 | 65 | M | Renal Cell | L2 | PMMA | E | 80 | 0 |

| 30 | 66 | M | Melanoma | T12 | PMMA | C | 50 | 4 |

| 31 | 51 | F | Renal Cell | L2 | Cage | C | 40 | 4 |

| 32 | 64 | F | Breast | T12, L1 | PMMA | D | 70 | 2 |

Patients were not randomized to the method of anterior reconstruction. This was a decision taken by the senior surgeon based primarily on life expectancy and also intraoperative factors such as blood loss and difficulty in cage insertion. EBL was recorded at the end of the surgery by an individual from the anesthesia department, who was blinded as to the surgical approach used.

Preoperative radiographic evaluation included plain X-ray films, computerized tomography scans, and magnetic resonance (MR) images. Imaging revealed greater than 50% lytic destruction of the VB in all patients. Postoperatively plain radiographs were typically used to assess the integrity of spinal implants and MR imaging was performed to assess local tumor recurrence at 3–6 month intervals, or as clinically needed. Pre- and postoperative degree of kyphosis was measured and compared. We could not measure the kyphotic angle in 6 cases (3 in the PMMA group and the other 3 in the EC group) as the lesions were at L3 and L4.

Preoperative and postoperative assessments included pain, functional outcomes, and performance status. Pain self-assessment was rated on a visual analog scale (VAS). Functional outcomes were assessed using the ASIA Improvement Scale. The performance status was assessed using the ECOG grading system and KPS. Data were collected by independent observers using standardized data collection forms and the time-points for data collection were immediately before surgery and at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show two illustrative cases.

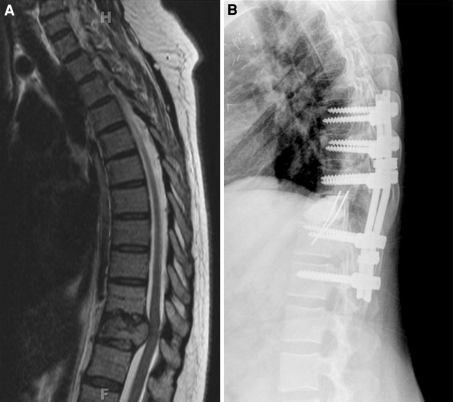

Fig. 1.

62 year old female with T11 metastatic melanoma. a Preoperative sagittal T2 weighted MRI of thoracic spine showing T11 tumor with cord compression. b Reconstruction with PMMA/pins

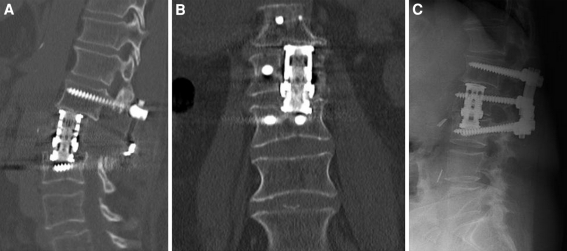

Fig. 2.

51 year old with history of L2 renal cell carcinoma. a, b Preoperative sagittal T2 weighted MRI and axial post contrast MRI showing L2 tumor with epidural extension

Fig. 3.

a, b Sagittal and coronal postoperative CT showing reconstruction with expendable cage. Subsidence of the cage in the inferior endplate is seen, with the cage abutting to the pedicle screw. c This did not compromise the final outcome as seen in the 1 year follow-up (lateral radiograph)

Data collected were then subjected to statistical analysis. Comparison for individual patient data was performed with a paired t test. Comparison between groups was performed using an unpaired t test.

Results

There were no long term survivors. The overall mean survival was 17 months (median: 16, range: 13–27 months), 17.5 in the EC vs 16.6 in the PMMA group (p = 0.5). Mean EBL was 1165 ml (median: 800 ml). No differences were found between groups: 1206 ± 897 ml, in the EC group vs 1125 ± 900 ml in the PMMA group (p = 0.8).

On presentation, the PMMA group had a mean Cobb angle of 16.36° ± 9.10°. Postoperatively, we demonstrated a mean Cobb’s angle of 10.91° ± 10.57°, with a 5.45° ± 5.79° reduction in kyphotic angle. In contrast, the EC group presented with mean pre-operative and post-operative Cobb’s angles of 20.53° ± 13.42° and 10.49° ± 11.56°, respectively. This group showed 10.04° ± 11.18° improvements in kyphotic deformity. No statistical differences were observed between the two groups in pre-operative (p = 0.31) or post-operative kyphosis (p = 0.91), whereas there was a non-significant a trend favoring EC reconstruction in kyphosis reduction (p = 0.16).

There was no deterioration of neurological function in any of the patients. All patients except two improved in their functional outcomes, 10 patients were ASIA Grade C, four of them improved to ASIA Grade E, and six patients improved to ASIA Grade D. Ten patients were Grade D, eight of them improved to ASIA Grade E, and two remained the same. All patients that presented with ASIA Grade E remained the same grade postoperatively. All patients had good-to-excellent performance status (ECOG Grades 0–2). The mean ECOG grade in PMMA group improved from 2.4 to 1.6, while in the EC group improved from 2.5 to 1.5 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of outcome between the two groups

| VAS | ECOG | EBL | Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-OP | Post-OP | Pre-OP | Post-OP | |||

| Cage | 7.9 (7–10) | 4 (0–6.2) | 2.5 (0–4) | 1.5 (0–3) | 1206 ml (300–3000) | 17.5 months (13–27) |

| PMMA | 8.1 (6–10) | 4.2 (0–6) | 2.5 (0–4) | 1.6 (0–4) | 1125 ml (300–3500) | 16.6 months (13–22) |

Values represent mean and range (in parentheses)

All patients reported improvement of their pain score after surgery, VAS improved from a mean of 8.1–4.2 in the PMMA group, and from mean of 7.9–4 in the EC group. No statistically significant difference in performance status or VAS improvements were observed between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Complications

There were a total of seven major surgical complications (21.9%). One patient was found to have a malpositioned pedicle screw causing postoperative radicular pain and another had hardware failure (EC group) (Fig. 3). Both of these patients required reoperation. A total of five patients (15.6%) were identified with wound infections, with history of prior radiation treatment (3 in the EC group and 2 in the PMMA). Three developed wound dehiscence. All of these patients required reoperation for surgical debridement and one for free flap coverage. Numbers were small to allow for any meaningful statistical analysis.

Discussion

The aim of the operation in metastatic disease is to perform an adequate tumor resection, allowing spinal decompression and immediate stabilization, without compromising functional outcome. Surgery must be executed in an expedited and safe fashion, especially in cancer patients. Because usually tumor involves the vertebral bodies and pedicles, the majority of the patients need stabilization of both anterior and posterior spinal columns [3, 9, 13].

Anterior approaches offer good exposure to the vertebral body, allowing decompression of the neural elements, with little or no access to the posterior elements and may carry significant morbidity if access is required through the thoracic cavity. Posterolateral approaches (transpedicular, costotransversectomy, lateral extracavitary) allow for circumferential spinal decompression and reconstruction through a single approach. Combined approaches provide access to anterior and posterior elements but are associated with increasing operative time, blood loss, and potential complications. Selection of the most appropriate surgical approach depends on the tumor location and size, patient health and associated comorbidities [6, 8, 12, 14, 15].

The rationale for surgery should be based on the expected goals of therapy and the longevity of the patient. Once the corpectomy and decompression are performed, immediate spinal stability must be achieved. The anterior column can be reconstructed using PMMA, bone graft, titanium mesh, ECs or combination thereof. PMMA is well known for reconstruction of the anterior column in spinal oncology [1]. There are both advantages and disadvantages associated with its use. It is not affected by radiotherapy and may have a local tumor control secondary to heat production at the bone cement interface and monomer toxicity. For those reasons it has been extensively used as adjuvant treatment in orthopedic oncology [16, 17]. As the PMMA hardens, the polymerization reaction is exothermic and potentially can cause thermal injury to the neural structures. The Steinmann pins used to scaffold the cement to the vertebral bodies can hinder MR imaging of the tumor bed. It also has the potential disadvantage of dislodgment or injuries to adjacent vascular structures [12, 18]. When compared to the cost of titanium implants, PMMA is much cheaper.

Bone grafts and titanium mesh are sized before insertion. They are difficult to place anteriorly from a posterior corridor if the working space is narrow; and there is no ability for further distraction.

Anterior column reconstruction and stabilization using ECs has also been described. EC are available in multiple sizes and can be used for the thoracic as well as the lumbar spine. They have the advantage of being inserted in a collapsed position with expansion in situ; they are especially useful for anterior column reconstruction through a posterior approach [5, 11, 19, 20]. Unlike PMMA, EC offer a chance for fusion of the anterior column.

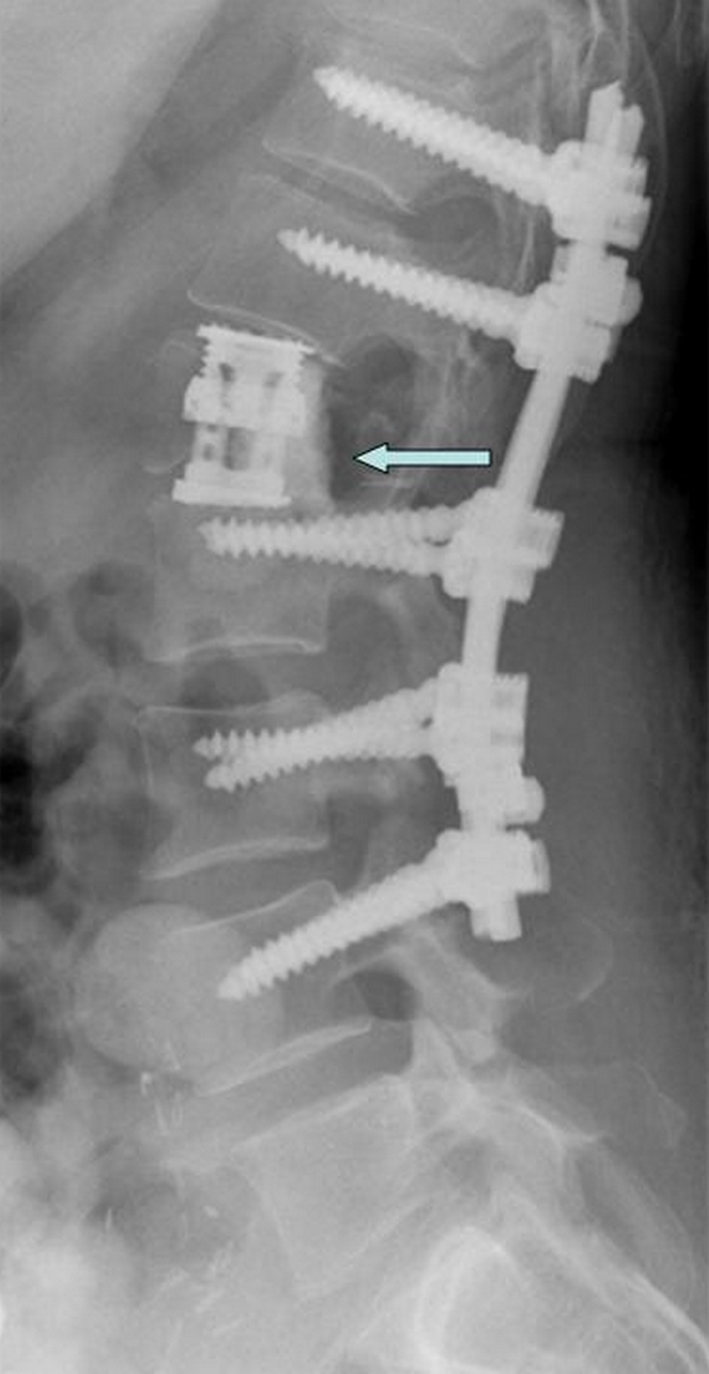

The decision on which method to use is based on operative factors and general medical status. Limited life expectancy (especially less than 6 months) shifts the trend towards PMMA to avoid unnecessary costs, whereas long term survivors would benefit from EC with potential for anterior column fusion. Intraoperative complications may obviate the need for faster reconstruction (PMMA). Finally difficulty in cage insertion or proper cage alignment may force the surgeon to resort to reconstruction with PMMA/pins. In a few cases of near-total vertebrectomy we have used a “hybrid” construct (not included in this series), where after cage placement we add PMMA around the cage to provide further stability until fusion is accomplished (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

54 year old female with L1 metastatic leiomyosarcoma. Lateral radiograph shows reconstruction with cage reinforced by PMMA (blue arrow)

In our study, there was no difference in survival and the estimated blood loss was similar in both groups, in line with reported literature [5, 11, 13]. The comparison between the PMMA and the EC group showed that there was no statistical difference in kyphotic angle reduction or improvement in VAS/performance status. The morbidity of a posterior corpectomy and vertebral column reconstruction is not insignificant. We identified 7 complications (21.9%) in our patients, with infection being the most frequent. Radiation therapy (RT) is a definite risk factor for the development of infection and we typically wait for 3–4 weeks before initiation of radiation to minimize wound breakdown. We also avoid preoperative RT due to increased rates of infection and because surgery has proven to be superior to RT alone in radioresistant tumors with cord compression [21]. Wang et al. reported 140 consecutive patients who underwent a single posterior approach with circumferential decompression and anterior reconstruction with PMMA/Steinmann pins. They reported a 30-day major complication rate of 14.3%, and when the 11% reoperation rate is considered, the overall major complication rate was 25.3%. The median EBL was 1500 ml [22]. Street et al. also reported their series on anterior reconstruction with PMMA and Steinmann pins. Twenty major complications were recorded in 11 patients (26%): 2 cases of multiorgan failure and 5 (12%) cases of wound dehiscence all requiring reoperation [23]. Shen et al. reported on 21 prospectively followed patients of thoracic and lumbar tumors operated by a posterior approach using EC. They reported a complication rate of 14.3%. EBL was 1.360 cc (range 200–2,500) [20].

There are certain limitations to our study, as it is a retrospective study with no control group and a small number of patients. Therefore, the level of recommendation is low. However, this is a series from a single institution in a uniform patient population and we believe that a useful conclusion can be drawn. With proper patient selection, both reconstruction methods can lead to comparable results in regards to kyphosis correction, construct longevity, and clinical outcome.

Conclusion

Reconstruction of the anterior vertebral column and providing immediate stability following tumor resection and corpectomy can be achieved using either PMMA or an EC. Both options allow for correction of the kyphotic deformity, and stabilization of the anterior vertebral column with similar functional and performance status outcomes in the lumbar and thoracolumbar area. PMMA is more cost effective than EC; however, fusion is more likely to occur with cage packed with bone graft in long term survivors.

Abbreviations

- ASIA

American Spinal Injury Association

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- KPS

Karnofsky performance status

- ESCC

Epidural spinal cord compression

- PTA

Posterolateral transpedicular approach

- EC

Expandable cage

- PMMA

Polymethylmethacrylate

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- MR

Magnetic resonance

References

- 1.Bilsky MH, Boland P, Lis E, Raizer JJ, Healey JH. Single-stage posterolateral transpedicle approach for spondylectomy, epidural decompression, and circumferential fusion of spinal metastases. Spine. 2000;25:2240–2249. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200009010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crocker M, Chitnavis B. Total thoracic vertebrectomy with anterior and posterior column reconstruction via single posterior approach. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:28–31. doi: 10.1080/02688690601170676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SN, Donthineni R. Surgical management of metastatic spine tumors. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pateder DB, Kebaish KM, Cascio BM, Neubaeur P, Matusz DM, Kostuik JP. Posterior only versus combined anterior and posterior approaches to lumbar scoliosis in adults: a radiographic analysis. Spine. 2007;32:1551–1554. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dc0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sciubba DM, Gallia GL, McGirt MJ, Woodworth GF, Garonzik IM, Witham T, Gokaslan ZL, Wolinsky JP. Thoracic kyphotic deformity reduction with a distractible titanium cage via an entirely posterior approach. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:223–230. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255385.18335.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutsch H, Boco T, Lobel J. Minimally invasive transpedicular vertebrectomy for metastatic disease to the thoracic spine. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:101–105. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31805fea01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamat A, Gilkes C, Barua NU, Patel NR. Single-stage posterior transpedicular approach for circumferential epidural decompression and three-column stabilization using a titanium cage for upper thoracic spine neoplastic disease: a case series and technical note. Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:92–98. doi: 10.1080/02688690701671029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales Alba NA. Posterior placement of an expandable cage for lumbar vertebral body replacement in oncologic surgery by posterior simple approach: technical note. Spine. 2008;33:E901–E905. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818b8a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman PJ, Suki D, McCutcheon I, Wolinsky JP, Rhines LD, Gokaslan ZL. Surgical management of metastatic disease of the lumbar spine: experience with 139 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:550–563. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lifshutz J, Lidar Z, Maiman D. Evolution of the lateral extracavitary approach to the spine. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16:E12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snell BE, Nasr FF, Wolfla CE. Single-stage thoracolumbar vertebrectomy with circumferential reconstruction and arthrodesis: surgical technique and results in 15 patients. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:ONS-263–ONS-268. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000209034.86039.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt T, Shen FH, Arlet V. Expandable cage placement via a posterolateral approach in lumbar spine reconstructions. Technical note. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:271–274. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.5.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vrionis FD, Small J. Surgical management of metastatic spinal neoplasms. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.5.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liljenqvist U, Lerner T, Halm H, Buerger H, Gosheger G, Winkelmann W. En bloc spondylectomy in malignant tumors of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:600–609. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt MH, Larson SJ, Maiman DJ. The lateral extracavitary approach to the thoracic and lumbar spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker WT, Dohle J, Bernd L, Braun A, Cserhati M, Enderle A, Hovy L, Matejovsky Z, Szendroi M, Trieb K, Tunn PU. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1060–1067. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan EC, Nelson C, Neff JR. Thermodynamic considerations of acrylic cement implant at the site of giant cell tumors of the bone. Med Phys. 1986;13:233–239. doi: 10.1118/1.595902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toksvig-Larsen S, Johnsson R, Stromqvist B. Heat generation and heat protection in methylmethacrylate cementation of vertebral bodies. A cadaver study evaluating different clinical possibilities of dural protection from heat during cement curing. Eur Spine J. 1995;4:15–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00298412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou D, Wang VY, Gupta N. Transpedicular corpectomy with posterior expandable cage placement for L1 burst fracture. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen FH, Marks I, Shaffrey C, Ouellet J, Arlet V. The use of an expandable cage for corpectomy reconstruction of vertebral body tumors through a posterior extracavitary approach: a multicenter consecutive case series of prospectively followed patients. Spine J. 2008;8:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, Mohiuddin M, Young B. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:643–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66954-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JC, Boland P, Mitra N, Yamada Y, Lis E, Stubblefield M, Bilsky MH. Single-stage posterolateral transpedicular approach for resection of epidural metastatic spine tumors involving the vertebral body with circumferential reconstruction: results in 140 patients. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:287–298. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.1.3.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Street J, Fisher C, Sparkes J, Boyd M, Kwon B, Paquette S, Dvorak M. Single-stage posterolateral vertebrectomy for the management of metastatic disease of the thoracic and lumbar spine: a prospective study of an evolving surgical technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:509–520. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180335bf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]