Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the correlation between Nurick grade and modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) scores in the preoperative and postoperative follow-up evaluation of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM). This retrospective study included 93 patients with CSM who underwent central corpectomy (CC) between 1998 and 2008. Preoperative and postoperative Nurick grade and total mJOA (tmJOA) and lower limb mJOA (llmJOA) score of each patient was documented and the correlation between the Nurick grades and the mJOA scores was studied. At presentation and follow-up, correlation between Nurick grade and llmJOA (Spearman’s ρ 0.901 and 0.886) was better than with tmJOA (0.846 and 0.862). The Nurick grade recovery rate (NGRR) correlated better with the llmJOARR than with tmJOARR (Spearman’s ρ 0.840 and 0.793, respectively). Overall, the correlation of preoperative and follow-up scores and recovery rates was better in patients with moderate myelopathy than in those with mild or severe myelopathy. At follow-up, 78/93 (83.9%) patients had improved in their Nurick grades, whereas 88/93 (94.6%) had improved in their tmJOA scores and 73/93 (78.5%) in their llmJOA scores. Although Nurick grade and llmJOA had good correlation preoperatively, at follow-up evaluation after surgery, there was disagreement in 11.8% (11/93) patients. One of the major reasons for the discrepancy between the Nurick scale and the llmJOA at follow-up evaluation was the ability of patients to regain employment without an improvement in the llmJOA score. As disease-specific scales, both Nurick scale and mJOA score should be utilized in the evaluation of patients with CSM.

Keywords: Cervical spondylotic myelopathy, Functional scales, Outcome, Recovery rates, Corpectomy

Introduction

A number of scales are available to assess functional disability in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) [4, 8–12]. The two commonly used scales are the Nurick grade and modified Japanese Orthopaedic association (mJOA) scoring system (Tables 1, 2). It is unclear whether these two functional scoring systems, especially the lower limb component of the mJOA (llmJOA) and the Nurick grade, provide similar evaluations of patients with CSM. Nurick grade assesses ambulatory status and so does the llmJOA. Thus, it would be rational to presume that the llmJOA score would correlate with Nurick grade better than the total mJOA (tmJOA) score. If the correlation between the Nurick grade and the tmJOA or the llmJOA is perfect then perhaps the Nurick grading system would be redundant. On the other hand, if the two instruments complement each other then it would be justified to utilize both of them in a given patient. Only few studies have compared Nurick grading and mJOA score in evaluating functional disability and outcome in patients with CSM [12]. Even these have evaluated the correlation in a small number of patients or in patients undergoing different types of decompressive surgery.

Table 1.

Nurick grades [7]

| 0 | Signs or symptoms of root involvement but without evidence of spinal cord disease |

| 1 | Signs of spinal cord disease but no difficulty in walking |

| 2 | Slight difficulty in walking which did not prevent full-time employment |

| 3 | Difficulty in walking which prevented full-time employment or the ability to do all housework, but which was not so severe as to require someone else’s help to walk |

| 4 | Able to walk only with someone else’s help or with the aid of a frame |

| 5 | Chair bound or bedridden |

Table 2.

Modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scoring system [1]

| Score | Definition |

|---|---|

| Motor dysfunction | |

| Upper extremities | |

| 0 | Unable to move hands |

| 1 | Unable to eat with a spoon but able to move hands |

| 2 | Unable to button shirt but able to eat with a spoon |

| 3 | Able to button shirt with great difficulty |

| 4 | Able to button shirt with slight difficulty |

| 5 | No dysfunction |

| Lower extremities | |

| 0 | Complete loss of motor & sensory function |

| 1 | Sensory preservation without ability to move legs |

| 2 | Able to move legs but unable to walk |

| 3 | Able to walk on flat floor with a walking aid (cane or crutch) |

| 4 | Able to walk up- &/or downstairs w/aid of a handrail |

| 5 | Moderate-to-significant lack of stability but able to walk up- &/or downstairs without handrail |

| 6 | Mild lack of stability but able to walk unaided with smooth reciprocation |

| 7 | No dysfunction |

| Sensory dysfunction | |

| Upper extremities | |

| 0 | Complete loss of hand sensation |

| 1 | Severe sensory loss or pain |

| 2 | Mild sensory loss |

| 3 | No sensory loss |

| Sphincter dysfunction | |

| 0 | Unable to micturate voluntarily |

| 1 | Marked difficulty in micturition |

| 2 | Mild-to-moderate difficulty in micturition |

| 3 | Normal micturition |

We performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of 93 patients who underwent uninstrumented central cervical corpectomy (CC) for CSM, in an attempt to determine the correlation between Nurick grade and mJOA both before and after surgery.

Clinical materials and methods

We prospectively gathered data in 93 patients with CSM who underwent uninstrumented CC with autologous bone grafting between 1998 and 2008. There were 87 men and 6 women. The mean age (±SD) of the patients was 48.4 ± 9.3 years (range 31–69 years). The mean duration of symptoms (±SD) was 22.9 ± 33.5 months (1–180 months). The mean duration of follow-up (±SD) was 18.9 ± 12.4 months (7–77 months). The first follow-up was between 6 and 18 months following surgery. Preoperative and postoperative Nurick grade and tmJOA and llmJOA score of each patient was documented.

An uninstrumented CC using either iliac bone graft or a fibular graft (for 3-level CC) was performed. All patients except those undergoing 3-level CC were mobilized in the immediate postoperative period with a Philadelphia collar that was prescribed for 6 months. Patients who underwent 3-level CC with fibular grafts were mobilized within a few days to a week postoperatively. The surgical technique has been described in previous publications [8].

Preoperative tmJOA score based grading of severity

The severity of functional disability was graded based on the preoperative tmJOA score as (1) mild, tmJOA score >12; (2) moderate, tmJOA score 9–12; and (3) severe, tmJOA score <9.

Statistical analysis

The pre- and postoperative Nurick grade and tmJOA score and llmJOA score were compared and the correlation between the Nurick grade and mJOA scores was analysed. After entering the data into an Excel spreadsheet, analysis was done using commercially available software (SPSS version 16.0, SPSS Inc.). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyse whether the postoperative changes in Nurick grade, tmJOA scores and llmJOA scores were significant. Postoperative recovery rates were calculated using the following formulae [4, 9]:

|

Spearman’s rho was used to determine the strength of association between Nurick grade, tmJOA and llmJOA scores, changes in these scores after surgery and the respective recovery rates. Scatter plots were drawn for categorical change in Nurick grade following surgery against corresponding tmJOA and llmJOA recovery rate as well as their categorical change. A p value of < 0.001 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Correlation between Nurick grade and mJOA scores (Table 3)

Table 3.

Preoperative functional scores: Correlation between tmJOA and llmJOA scores and Nurick grades

| Nurick Grade(number of patients) | tmJOA score | llmJOA score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| 0 (1) | 16 | – | – | 7 | – | – |

| 1 (3) | 16 | 0.0 | – | 7 | 0.0 | – |

| 2 (12) | 14.6 | 1.2 | 12–16 | 5.3 | 0.8 | 4–6 |

| 3 (40) | 13.1 | 1.7 | 9–17 | 4.80 | 0.8 | 4–6 |

| 4 (28) | 9.8 | 1.2 | 6–12 | 3.0 | 0.0 | – |

| 5 (9) | 8.4 | 1.2 | 6–10 | 2.00 | 0.00 | – |

tmJOA total mJOA, llmJOA lower limb mJOA

The mean preoperative Nurick grade (±SD) was 3.3 ± 0.99 (range 0 –5). The mean preoperative tmJOA score (±SD) was 11.97 ± 2.6 (range 6–17). The mean preoperative llmJOA score (±SD) was 4.2 ± 1.4 (range 2–7). The correlation between Nurick grade and llmJOA (Spearman’s ρ 0.901) was better than with tmJOA (0.846) preoperatively.

The mean follow-up Nurick grade (±SD) was 1.8 ± 1.0 (range 0–4). The mean follow-up tmJOA score (±SD) was 15.8 ± 2.2 (range 9–18). The mean follow-up llmJOA score (±SD) was 5.8 ± 1.3 (range 3–7). The correlation between llmJOA and Nurick grades (Spearman’s ρ 0.886) was better than with tmJOA (0.862) at follow-up.

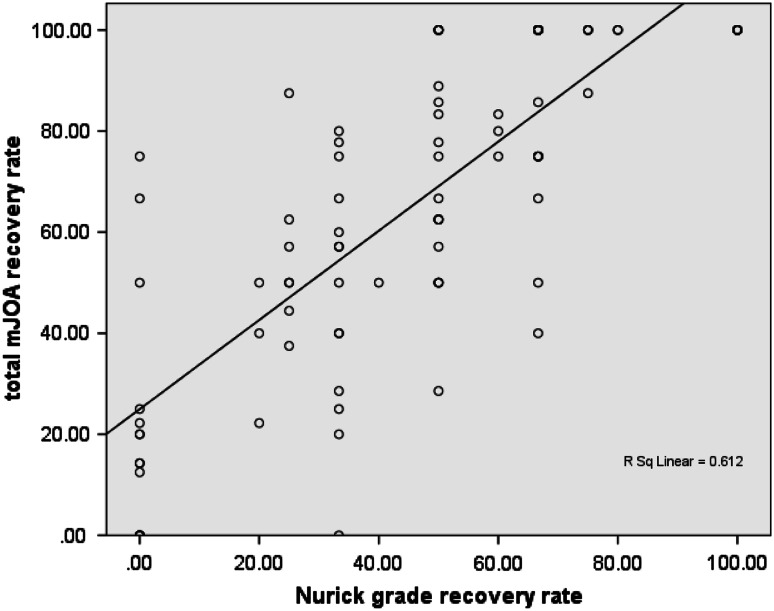

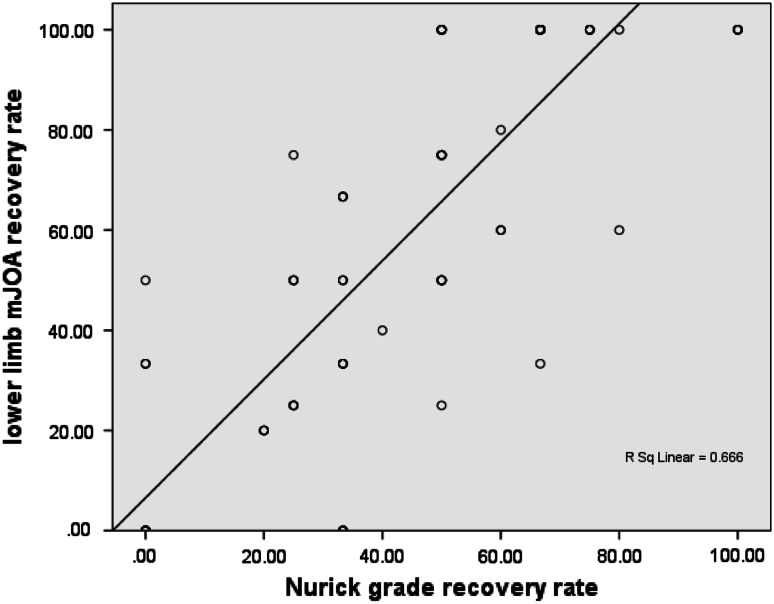

Correlation between NGRR and mJOARR

The mean Nurick grade recovery rate (±SD) was 45.8 ± 27.7 (range 0–100). The mean tmJOA recovery rate (±SD) was 65.2 ± 31.1 (range 0–100). The mean llmJOA recovery rate (±SD) was 59.9 ± 38.4 (range 0–100). The correlation between Nurick grade recovery rate and llmJOA recovery rate (Spearman’s ρ 0.840) was better than with tmJOA recovery rate (0.793) (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of total mJOA recovery rate versus Nurick grade recovery rate

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of lower limb mJOA recovery rate versus Nurick grade recovery rate

Correlation in different grades of myelopathy

Across all grades of myelopathy llmJOA scores correlated better with the preoperative, follow-up and change in Nurick grade after surgery than tmJOA scores. However, in the mild myelopathy group, preoperative tmJOA scores had better correlation with Nurick grade than the llmJOA. Overall, the correlation between mJOA scores and Nurick grades and recovery rates were better for the moderate myelopathy group than for the mild or severe myelopathy groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between Nurick grade and mJOA scores, changes in them and their recovery rates in different grades of myelopathy (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient)

| Mild myelopathy(tmJOA score >12) (n = 42) | Moderate myelopathy (tmJOA score 9–12) (n = 43) | Severe myelopathy (tmJOA score <9) (n = 8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tmJOA | llmJOA | tmJOA | llmJOA | tmJOA | llmJOA | |

| Preoperative NG | 0.507** | 0.456 | 0.605** | 0.986** | 0.149 | 1.00** |

| Follow-up NG | 0.742** | 0.876** | 0.878** | 0.817** | 0.811 | 0.927** |

| Change in NG | 0.628** | 0.623** | 0.768** | 0.819** | 0.895 | 0.917** |

| Mild myelopathy(tmJOA score >12) (n = 42) | Moderate myelopathy (tmJOA score 9–12) (n = 43) | Severe myelopathy (tmJOA score <9) (n = 8) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tmJOARR | llmJOARR | tmJOARR | llmJOARR | tmJOARR | llmJOARR | |

| NGRR | 0.721** | 0.862** | 0.857** | 0.806** | 0.905 | 0.902 |

NG Nurick grade, tmJOA total mJOA, llmJOA lower limb mJOA, NGRR Nurick grade recovery rate, tmJOARR total mJOA recovery rate, llmJOARR lower limb mJOA recovery rate

** Significant at p = 0.001

Correlation between changes in Nurick grade and mJOA scores

The percentage of patients who improved in their Nurick grade, tmJOA and llmJOA scores was 83.8 (78/93), 94.6 (88/93) and 78.5 (73/93), respectively.

Correlation between change in tmJOA and llmJOA scores and the Nurick grade at follow-up is shown in Table 5. The correlation between categorical change in Nurick grade was better with change in the llmJOA score (Spearman’s ρ 0.737) than with change in tmJOA score (0.679). There were no patients with worsening in any of the scales at follow-up. Also the degree of agreement between outcome assessed at follow-up by Nurick grade and llmJOA (88.2%) was better than between Nurick grade and tmJOA (87%) (Tables 6, 7).

Table 5.

Correlation between change in tmJOA and llmJOA scores and Nurick grade at follow-up

| Change in Nurick grade (number of patients) | Change in tmJOA | Change in llmJOA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| 0 (15) | 1.1 | 0.99 | 0–3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0–1 |

| ≥1 (78) | 4.4 | 2.2 | 0–10 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0–5 |

| ≥2 (46) | 5.1 | 2.2 | 1–10 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1–5 |

tmJOA total mJOA, llmJOA lower limb mJOA

Table 6.

Outcome by Nurick grade and tmJOA score (n = 93)

| Nurick grade | tmJOA score | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Same | ||

| Improved | 77 | 1 | 78 |

| Same | 11 | 4 | 15 |

| Total | 88 | 5 | 93 |

Fisher’s exact t test for significance p = 0.002

tmJOA total mJOA

Table 7.

Outcome by Nurick grade and llmJOA score (n = 93)

| Nurick grade | llmJOA score | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Same | ||

| Improved | 70 | 8 | 78 |

| Same | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| Total | 73 | 20 | 93 |

Fisher’s exact t test for significance p = 0.0000001

llmJOA lower limb mJOA

Discrepancy between changes in Nurick grade and mJOA scores

Among those in whom there was discordance, the proportion of patients in whom there was no improvement in llmJOA but had improvement in Nurick grade was higher (8/11 patients) than those in whom an improvement in llmJOA score did not translate into similar change in the Nurick grade (3/11 patients) (Table 7). Of the 8 patients in whom there was no improvement in llmJOA, 6 patients had improved from Nurick grade 3 to Nurick grade 2 (pre operative llmJOA was 6 in one patient, and 5 in three and 4 in the other two), and 2 patients had improved from Nurick grade 1 to 0. These two patients who had improved from Nurick grade 1 to 0 had no dysfunction on llmJOA preoperatively (score of 7).

Discussion

Previous reports of comparison between Nurick grade and mJOA scores

Though Nurick grade and mJOA score represent different functional capabilities, few studies have performed an in-depth analysis and comparison of the domains assessed by these two scoring systems. Several authors report results of decompressive surgery using either Nurick grade or mJOA score [2, 3, 5, 12]. Only few have reported patients’ functional status using both the functional scales [12].

In a retrospective study of 43 patients with CSM who underwent anterior decompression, Vitztum et al. [12] showed that there was good correlation between the preoperative and postoperative scores using the Nurick scale and JOA scoring system. This finding is similar to that of our study. However, a wide variation was noted in the outcome following surgery with only 33% of patients improving their Nurick grade whereas 81% had improved their JOA score. The authors attributed this difference to an improvement in upper limb and sensory function which is not reflected in the Nurick score. Interestingly, in our study, the variation in percentage of patients who showed an improvement in the Nurick grade, tmJOA and llmJOA scores was less, ranging from 78.5 to 94.6% for llmJOA and tmJOA scores, respectively, with the percentage of patients determined to have improved their Nurick grade being in between at 83.8%. Although Vitztum et al. [12] found a significant difference in the mean postoperative recovery rates assessed by the Nurick grade (23%) and JOA scoring system (37%), the variation was less than that noted for the percentage of patients showing improvement in the different functional scales. Hence, they concluded that to enable comparison across studies that have used CSM specific functional scales, it is more appropriate to report the mean recovery rate rather than the proportion of patients showing an improvement in the functional scores. The authors commented that Nurick scale is less sensitive to improvement following surgery and recommended the continued use of multiple scoring systems in assessing outcome following surgery in patients with CSM. A detailed analysis of the various components of individual scores (such as the llmJOA scores), however, was lacking in their study. Our results show that the variation in the mean recovery rates was less than that of the proportion of patients showing an improvement in the different functional grading systems.

Causes of discordance

The lack of significant correlation between preoperative llmJOA scores and Nurick grade in the mild myelopathy group can be explained by the impact of the disability in the lower limbs on the occupation which would have been reflected in a more severe Nurick grade in those whose employment was affected even with mild lower limb functional impairment. Similarly, the lack of correlation between preoperative tmJOA and Nurick grade in the severe myelopathy group is probably due to the poor upper limb or bladder function or sensory impairment in the setting of a moderate lower limb functional impairment, which resulted in low JOA scores but not in poor Nurick grades.

In our series of patients, there was disagreement in 12.9% (12 out of 93) patients between the Nurick grade and tmJOA and in 11.8% (11 out of 93) patients between the Nurick grade and llmJOA score in assessment of outcome at follow-up. The discrepancy between Nurick and tmJOA is expected as the functional domains assessed by the Nurick grade and mJOA vary significantly. King et al. [6], in their study for validating SF-36 in CSM, conclude that Nurick score and leg score of mJOA assess similar domains. However, if Nurick grade and llmJOA both assess ambulatory function, there should be minimal or no discrepancy between the scores obtained using the two scales at follow-up. The only flaw in this argument is the fact that Nurick grade assesses the employability of a patient along with ambulatory status. An improvement in ambulatory function may not be sufficient for a person to regain his/her ability to go to work. Hence, a positive change in llmJOA score may not be reflected in a similar change in the employment status as evidenced by change in the Nurick grade. Theoretically this should result in more patients showing an improvement in llmJOA at follow-up than in their Nurick grades. However, our results were contrary to this proposition.

The only explanation for the improvement in preoperative Nurick grade 3 to a follow-up Nurick grade 2 in 6 patients without a corresponding improvement in the llmJOA would suggest that these patients returned to work in spite of no improvement in their ambulatory status.

Disconnect between employment and ambulation

Nurick grade was devised primarily to assess ambulatory status of a patient and reflect its effect on employment. The premise was that an improvement in ambulatory status should translate into a similar change in the employment status of a person with CSM. This, however, does not hold true in our subset of patients as evidenced from the discordance between changes in llmJOA and Nurick grade at follow-up. The reasons for this apparent discrepancy may be manifold. One possibility is that significant improvement in lower limb function may not be necessary in certain occupations to remain employed. An example would be a grocery shop owner who just needs to sit at the cash counter of the shop and manage the counter without any need for him to move around. The other reason would be the nature of compensation in the absence of work. If a patient does not get any unemployment benefits, as happens in most developing countries, his economical needs may force him to work in spite of the less than ideal ambulatory function.

In other words, though Nurick grade can indicate whether a person is employable or not, it does not indicate whether an improvement in Nurick grade 3 to 2 is secondary to improvement in the ambulatory status. We are not suggesting that Nurick grade should no longer be used in outcome assessment, but that it should be supplemented with other functional scoring systems in assessment of outcome following decompressive surgery. The main advantages of the Nurick grading system is its simplicity and ease of use. It is also unique in providing a gross idea of the ambulatory and employment status of a patient at ‘one glance’ that cannot be acquired by any of the so-called “composite, all inclusive” scales for CSM. Although both Nurick grading and llmJOA score test ambulatory function, there are separate domains that are assessed by these scoring systems. Thus, it would be appropriate to use both these scoring systems in the assessment of preoperative disability and postoperative outcome in patients with CSM. The nature of employment, the consequences of losing the job and the provision of compensation or lack thereof play a complex role in the decision of a patient to return to his/her employment after surgery. Also the ability to continue daily practices such as squatting and sitting cross-legged do affect the outcome from the patients’ point of view. We need to evolve scoring systems that take into consideration these culture specific needs.

Utility of QOL instruments in CSM

More recently it is being advocated that assessment of patients with a chronic disease such as CSM, should be more comprehensive than reflecting purely on the physical impact of the disease. There has been a trend to study outcomes following surgery using generic scales for QOL (quality of life) and comparing them with the disease-specific scales such as the Nurick grading system and the mJOA. We have previously compared the Nurick grading system with more comprehensive scales in patients who underwent CC for CSM [9, 10]. Rajshekhar and Muliyil [9] compared a simple scale, namely the ‘patient perceived outcome score’ (PPOS) with NGRR. Though there was good correlation between the two, there was disagreement between them in 13.5% of patients. Thakar et al. [10] compared the Nurick grade and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and WHOQOL-Bref in patients undergoing uninstrumented CC for CSM. There was a good correlation between Nurick grade and the physical component summary (PCS) score of SF-36 and the physical domain of the WHOQOL-Bref but not with the overall SF 36 and WHOQOL-Bref scores. This again emphasizes the need for two separate scales, a disease-specific scale like Nurick grade for objective assessment of disease severity and a generic scale for multi-dimensional assessment of Health Related Quality-of-Life (HRQOL) [10]. Nurick grade in itself is inadequate for complete assessment and so is mJOA score as evidenced by disagreement between the respective recovery rates in the present study. However, these scores are unlikely to be replaced by more comprehensive HRQOL scales such as SF 36 or WHOQOL-Bref in clinical practice situations as they are simple and easy to administer.

Conclusion

Although Nurick grade and lower limb mJOA had good correlation at follow-up evaluation after surgery, there was disagreement in 11.8% (11 out of 93) patients. The correlation was best in patients with moderate myelopathy than in those with mild or severe myelopathy. The disagreement between the scores in some patients suggests that Nurick grade and mJOA scores assess separate domains of functionality. As disease-specific scales, we should continue to incorporate both Nurick scale and mJOA score in evaluation of patients with CSM till we evolve a comprehensive scoring system that reflects all aspects of function in a patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Miss Nithya Joseph and Visalakshi Jeyaseelan for their help in the statistical analysis of the data.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Benzel EC, Lancon J, Kesterson L, Hadden T. Cervical laminectomy and dentate ligament section for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:286–295. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung WY, Arvinte D, Wong YW, Luk KD, Cheung KM. Neurological recovery after surgical decompression in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy–a prospective study. Int Orthop. 2008;32(2):273–278. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0315-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chagas H, Domingues F, Aversa A, Vidal FAL, de Souza JM (2005) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 10 years of prospective outcome analysis of anterior decompression and fusion. Surg Neurol 64 Suppl 1:S1:30–35 doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2005.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hirabayashi K, Miyakawa J, Satomi K, Maruyama T, Wakano K. Operative results and postoperative progression of ossification among patients with ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 1981;6:354–364. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikenaga M, Shikata J, Tanaka C. Long-term results over 10 years of anterior corpectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy. Spine. 2006;31(14):1568–1574. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000221985.37468.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King JT, Jr, Roberts MS. Validity and reliability of the Short Form-36 in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(2 Suppl):180–185. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.2.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1972;95:87–100. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajshekhar V, Kumar GSS. Functional outcome after central corpectomy in poor grade patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1279–1285. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000159713.20597.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajshekhar V, Muliyil J. Patient perceived outcome after central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Surg Neurol. 2007;68(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh A, Gnanalingham K, Casey A, Crockard A. Quality of life assessment using the Short Form-12 (SF-12) questionnaire in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: comparison with SF-36. Spine. 2006;31(6):639–643. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000202744.48633.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakar S, Christopher S, Rajshekhar V. Quality of life assessment after central corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: comparative evaluation of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey and the World Health Organization Quality of Life–Bref. J. Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(4):402–412. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.SPINE08749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitzthum HE, Dalitz K. Analysis of five specific scores for cervical spondylogenic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2096–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0512-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]