The HSV-1 US1 gene encodes an ocular virulence determinant that is highly modified after translation. To better determine sequence variability in the protein, the gene was sequenced in six ocular isolates, and bioinformatics analysis was carried out. The data will be useful for designing structure-function studies.

Abstract

Purpose.

The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) US1 gene encodes host-range and ocular virulence determinants. Mutations in US1 affecting virulence are known in strain OD4, but the genomic variation across several strains is not known. The goal was to determine the degree of sequence variation in the gene from several ocular HSV isolates.

Methods.

The US1 gene from six ocular HSV-1 isolates, as well as strains KOS and F, were sequenced, and bioinformatics analyses were applied to the data.

Results.

Strains 17, F, CJ394, and CJ311 had identical amino acid sequences. With the other strains, most of the variability was concentrated in the amino-terminal third of the protein. MEME analysis identified a 63-residue core sequence (motif 1) present in all α-herpesvirus US1 homologs that were located in a region identified as structured. Ten amino acids were absolutely conserved in all the α-herpesvirus US1 homologs and were all located in the central core. Consensus-binding motifs for cyclin-dependent kinases and pocket proteins were also identified.

Conclusions.

These results suggest that significant sequence variation exists in the US1 gene, that the α22 protein contains a conserved central core region with structurally variable regions at the amino- and carboxyl termini, that 10 amino acids are conserved in α-herpes US1 homologs, and that additional host proteins may interact with the HSV-1 US1 and US1.5 proteins. This information will be valuable in designing further studies on structure-function relationships and on the role these play in host-range determination and keratitis.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a significant human pathogen causing diseases such as mucocutaneous ulcers, keratitis, and encephalitis. In the United States, HSV-1 is the leading cause of blindness from infection and the leading cause of sporadic encephalitis.1,2 Studies in animal models have shown that the severity of an HSV-1 infection depends on three factors. The first is the innate resistance of the host. Strains of mice vary widely in their susceptibility, and some host genes involved in this innate immune resistance have been identified.3–8 The second factor is the host's acquired immune response. Animals with various defects in acquired immunity have difficulty in controlling viruses, resulting in lethal infections.9–14 The host immune response is crucial because corneal damage results from an immunopathological response.15–17

The third factor is the genetic makeup of the virus. Strains of HSV-1 display virulence patterns ranging from no disease to lethal encephalitis (see Refs. 18, 19 for review). The severity of keratitis also varies widely between strains. Although the sequence of one complete HSV-1 genome has been available for some time20–23 and two more genomes were recently sequenced,24 little is known about the total sequence divergence and the role most HSV-1 genes play in the severity of an infection. Deletion of certain genes from the virus can have significant effects on virulence, but in nature it is more likely that virulence differences are due to effects of multiple genes and the combination of alleles carried by a given strain of virus. This is supported by a study showing that transferring different combinations of genes from a moderately virulent strain (CJ394) into a highly attenuated strain of virus (OD4)25,26 resulted in different virulence patterns in mice. At least seven genes were shown to be involved in the virulence differences. One gene that, when transferred from CJ394 into OD4, increased ocular virulence but not neurovirulence was US1, and two sequence changes, S34A and Y116C, that must occur together, were suggested to play a role in the difference in virulence.25,26

The HSV-1 US1 protein (α22) is an immediate early (α) gene that regulates several processes in infected cells. In concert with the US3 and UL13 kinases, it alters the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II, and this is thought to target Pol II to the viral genome.27–31 The α22 protein is also responsible for the efficient expression of some late genes, including UL41, US11, UL47, UL49, UL13, and UL4.32–36 In addition, it plays a role in determining the composition of virions, possibly through effects on late gene expression,37 and negatively regulates α-gene expression.38,39 The α22 protein has also been reported to block B-cell activation of CD4+ T cells.40 The activities of the α22 protein are mediated by interactions with both viral and host proteins.27,32,41–46 The α22 protein is also heavily posttranslationally modified by serine and tyrosine phosphorylation, guanylylation, and adenylation, and multiple isoforms (at least seven or eight) are found in infected cells.25,36,47–52 The functions of each of the isoforms in infection and virulence are not understood.

In addition to the 420-amino acid α22 protein, a second protein, US1.5, is expressed from the US1 gene.53 The US1.5 protein is translated in the same reading frame as the α22 protein but is truncated at the n-terminus. Translation start sites for US1.5 have been reported at residues 171,52 147,53 and 90.54 The reason for the difference is not clear but may be due to the use of different strains of virus (F and KOS) in these studies. The US1.5 protein is found only at late times, and the levels are upregulated by the US3 kinase and downregulated by the UL13 kinase.55 The distinct or shared functions of α22 and US1.5 are not completely understood, but the US1.5 protein appears to downregulate cyclin expression in infected cells.46 The US1.5 protein has a diffuse cytoplasmic location whereas the α22 protein appears as punctate nuclear spots,32,44,56–58 but how this correlates with the functions of the two proteins is not clear.

Studies on the role of the HSV-1 US1 gene in virulence are hampered by a lack of knowledge of the degree of sequence variability between strains. To address these deficiencies, we sequenced the US1 gene from eight HSV-1 strains and applied a bioinformatics analysis of the sequence data. The results show that there is significant sequence heterogeneity between the US1 genes concentrated primarily in the amino-terminal third of the protein. In addition, we identified a 63-amino acid motif in the center of the protein, determined that 10 amino acid residues are absolutely conserved in all α-herpesvirus US1 homologs, and identified putative binding motifs for host proteins. These data provide information critical for designing mutagenesis strategies that can be used to study the structure and function of the α22 protein and the role it plays in virulence and host range.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Viruses

Vero cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 5% serum and antibiotics, as described previously.59 The viral sequences analyzed in this study are listed in Table 1. The ocular virulence characteristics of HSV-1 strains OD4, CJ311, CJ394, 994, 970, TFT401, and KOS were described previously.59,60 Briefly, HSV-1 strain OD4 is avirulent with multiple attenuating mutations.25,59,60 Strain CJ994 causes mild stromal keratitis. Viral strains CJ394 and TFT401 cause moderate stromal keratitis. HSV-1 KOS produces moderately severe keratitis, with <20% mortality in 5- to 6-week-old mice. Mice infected with strain CJ311 exhibit severe blepharitis, and 70% of the mice die of encephalitis before stromal keratitis develops. Strain CJ970 causes severe stromal disease and 50% mortality. Strain F is a commonly used laboratory strain and is neurovirulent after peripheral inoculation.61

Table 1.

Herpesvirus Species Names, Gene Designations, and Accession Numbers

| Virus Species | Virus Name Abbreviation | Strain | US1 Gene Homolog Designation | Accession No. (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alphaherpesvirinae | ||||

| Simplexvirus | ||||

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | OD4 | US1 | JF511471 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | 994 | US1 | JF511474 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | CJ394 | US1 | JF511469 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | TFT401 | US1 | JF511475 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | CJ311 | US1 | JF511470 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | CJ970 | US1 | JF511472 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | KOS | US1 | JF511473 |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | Strain F | US1 | GU734771.1* |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | Strain 17 | US1 | 2703435† |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | HF10 | US1 | DQ889502* |

| HSV-1 | HSV-1 | R-15 | ORF_07R | AY344654* |

| HSV-2 | HSV-2 | HG52 | US1 | 1487350† |

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus 2 | SA8 | B264 | US1 | 3190318† |

| Mardivirus | ||||

| Gallid herpesvirus 2 | GaHV-2 | Md5 | MDV088 | 4811543† |

| Varicellovirus | ||||

| Human herpesvirus 3 | VZV | 03–500 | ORF63 | ABF21862 |

| Independent branch | ||||

| Duck enteritis virus | DEV | DEV Clone-03 | US1 | EF524095 |

Gene ID not available.

Gene ID references.

Viral DNA Isolation

Viral DNA was isolated using a modification of a previously described large-scale preparation.62 Briefly, 10 confluent 10-cm plates of Vero cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0. The plates were scraped 24 hours after they reached 100% cytopathic effect, and the cells were pelleted at 2000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 mL of medium, subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles (−80°C/37°C), and centrifuged at 2000g to remove debris. The supernatants were then combined, layered onto a 36% sucrose cushion in reticulocyte standard buffer (RSB; 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2), and then centrifuged for 80 minutes at 13,500 rpm in a rotor (Beckman SW28; Beckman-Coulter Inc., Brea, CA). The viral pellet was resuspended in 5 mL TE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA) with 0.15 M sodium acetate and 50 μg/mL RNase A and was incubated 30 minutes at 37°C. Proteinase K and SDS (50 μg/mL and 0.1% respectively) were then added, and the solution was incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The viral DNA was then purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, resuspended in deionized water, and stored at −20°C.

Sequencing the US1 Gene from Multiple Strains

To obtain the US1 sequence from strains F, KOS, OD4, CJ394, TFT401, CJ311, 970, and 994, the US1 gene was amplified from purified viral genomic DNA and then directly sequenced. To amplify the US1 gene, we performed a PCR reaction consisting of 2.5 μg viral DNA, 1× reaction buffer, 1× enhancer buffer, 1 mM MgSO4, 4 mM dNTP, 0.1 μg each primer, and 1 μL Pfx high-fidelity polymerase (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA) in a total volume of 50 μL The cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 94°C for 5 minutes, 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 2 minutes, and a final cycle of 58°C for 7 minutes. The US1 gene extends between genome nucleotides 132,363 and 133,906. The forward primer annealed at nucleotide 132,363 (5′-TTTTGCACGGGTAAGCAC-3′), and the reverse primer annealed at nucleotide 133,992 (5′-CCGACTTCCTCACATCTGCT-3′). The PCR products were directly sequenced using multiple primers (Table 2). The sequencing mixture consisted of 200 μg amplification product, 1× reaction buffer, 0.1 μg primer, and 2 μL dye terminator (Big Dye, v3.1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a total volume of 20 μL. The cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 95°C for 3 minutes, 45 cycles of 95°C for 20 seconds, 45°C for 30 seconds, and 60°C for 4 minutes followed by a final cycle of 72°C for 7 minutes. Sequences were determined at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center sequencing facility. To reconcile discrepancies in the sequence, chromatograms were visually inspected or sequencing reactions were repeated. The constructs were sequenced and found to match the sequences of the original strains.

Table 2.

Catalog of Primers Used for Direct Sequencing of the US1 Gene Amplicons

| Forward or Reverse Primer | Genome Nucleotide Location | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Forward | 132, 363 | 5′ TTTTGCACGGGTAAGCAC 3′ |

| Forward | 132, 782 | 5′ CAGCCTTGGAGTCTCGAGGTCG 3′ |

| Forward | 133, 141 | 5′ AAGCCCAATGCAATGCTAC 3′ |

| Forward | 133, 464 | 5′ GCAAGCTTCCTTGTTTGGAG 3′ |

| Reverse | 133, 006 | 5′ TGGGGGAATGTCGTCATAAGA 3′ |

| Reverse | 133, 245 | 5′ ACCCGAAACAGCTGATTGAT 3′ |

| Reverse | 133, 716 | 5′ GTCCAGTCAAACTCCCCAAA 3′ |

| Reverse | 133, 992 | 5′ CCGACTTCCTCACATCTGCT 3′ |

Sequence Analysis

The sequences used for analysis were derived from this work and from sequences available in GenBank, as shown in Table 1. The nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned with ClustalW63 assuming no gaps. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis package (MEGA464). The nucleotide-based bootstrap consensus tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm65 and the Kimura 2-paramter method66 and was derived from 1000 replicates.67 The bootstrap consensus tree constructed with amino acid sequence data was generated using the neighbor-joining algorithm and the JTT matrix-based method68 derived from 1000 replicates. Analysis with minimum evolution (ME) and maximum-parsimony methods produced similar results. Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation (MEME;69) analysis used the zoops (zero or one motif) algorithm to determine the presence and absence of motifs in the target sequences. The number of motifs (n = 10) reported was limited to motifs that had the potential to be phylogenetically informative. The optimum motif width specified in analysis ranged from 35 to 80, and the optimum number of sites for each motif varied from 2 to 50. Motifs revealed in the summary MEME analysis were conservatively excluded to limit the number of false-positive motif placements. The ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous substitutions for the HSV-1 US1 sequences was performed using SNAP (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/SNAP/SNAP.html70).

Protein Folding and Structural Feature Prediction

Identification of putative folded globular regions of the α22 protein was performed using Globplot2 (http://globplot.embl.de71). Short functional site prediction using the Strain 17 sequence was performed using ELM (http://elm.eu.org72).

Results

The US1 genes from six independent low-passage ocular isolates of HSV-1 and the laboratory strains KOS and F were sequenced. The US1 sequence from our strain F matched the recently deposited strain F, and we refer to that accession number. This information was combined for analysis with available sequence data for strain 17 and other α-herpesvirus US1 homologs, as shown in Table 1.

Sequence Divergence between HSV-1 US1 Genes

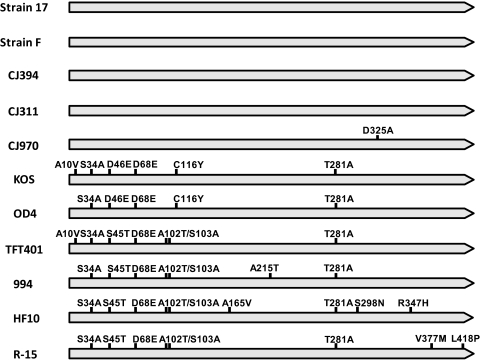

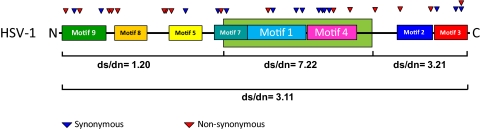

A schematic diagram summarizing the amino acid sequence differences between all of the 11 HSV-1 US1 genes available for analysis is shown in Figure 1. Four strains—17, F, CJ394, and CJ311—had identical US1 sequences. Strain CJ970 differed from the strain 17 group by only one amino acid (D325A). The remainder of the strains had between 5 and 9 amino acid differences compared with strain 17. These results and others shown suggest that US1 has a central conserved core and that most of the variability occurs in the amino-terminal third of the protein. To confirm this, we compared the ratio of synonymous to non-synonymous mutations. As shown in Figure 2, the central core clearly had the highest ratio (ds/dn = 7.22), the carboxyl-terminal third was conserved but less so (ds/dn = 3.21), and the amino-terminal third had a ratio near 1 (ds/dn =1.2).

Figure 1.

Sequence variability in the HSV-1 US1 (α22) protein. Filled arrows: US1 protein for each strain of virus, with amino acid differences indicated by vertical bars with the sequence differences noted. Only the amino acids different from the strain 17 sequence are shown.

Figure 2.

Diagram plotting both synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions along the length of the HSV-1 α22 protein. The ratio of synonymous to non-synonymous substitutions was determined for both the whole protein and the major segments.

Phylogenetic Analysis of US1 Genes

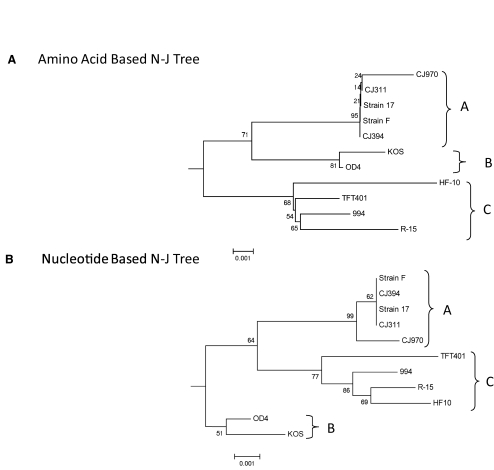

Figure 3A shows the neighbor-joining tree for the HSV-1 US1 amino acid sequences using HSV-2 strain HG52 as the out group. Similar results were obtained using maximum-parsimony and maximum-likelihood methods, indicating the tree was robust. The maximum sequence divergence between the HSV-1 strains was 1.2%, and the HSV-1 strains clearly separated into three distinct groups or clades. The three-clade structure was seen previously, but the clades based on the US1 gene differ.73,74 Group A included strains 17, CJ970, CJ394, CJ311, and F. Only two strains (KOS and OD4) were in group B, and four strains (HF10, TFT401, 994, and R-15) were in group C. As shown in Figure 3B, the phylogenetic analysis based on the nucleotide sequences yielded the same three clade structures of amino acid sequences, although the topology of the tree was slightly different.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among US1 sequences of HSV strains. (A) Neighbor-joining tree based on amino acid sequence data. (B) Neighbor-joining tree generated with nucleotide sequence data. Each tree was generated using 1000 bootstrap replicates. The sequence of the HSV-2 strain HG52 US1 gene was used as the outgroup, but only the HSV-1 strains are shown. The three clades are denoted A, B, and C. The branch lengths are proportionate to the amount of evolutionary change and the scale to either nucleotide or amino acid replacement per position, respectively. The sequences of strains CJ970, CJ311, CJ394, F, KOS, OD4, TFT401, and 994 were generated for this study. All the HSV-1 strains, except F and KOS, are low-passage clinical isolates obtained from the Seattle, Washington, area. All other sequences were obtained from the NCBI GenBank database (Table 1).

MEME Analysis for Conserved Motifs

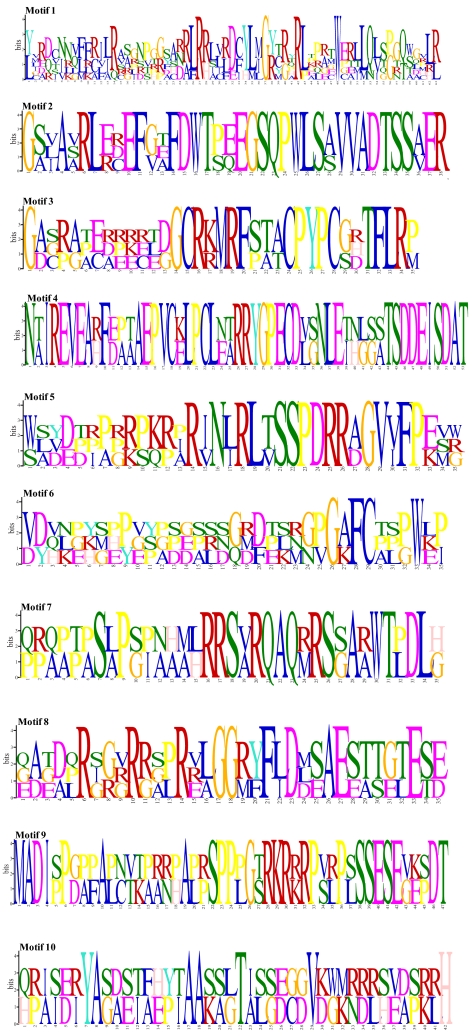

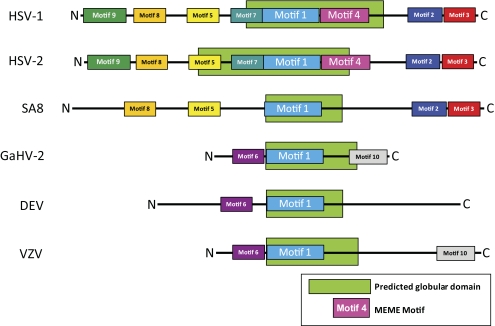

MEME analysis, which identifies statistically significant motifs in a data set, was used to identify 10 phylogenetically informative amino acid sequence motifs (Figs. 4, 5). A core motif (motif 1) was identified in all α-herpesvirus US1 genes and their homologs and is, thus, distinctive for all α-herpesviruses. This motif had the lowest expectation value (2 × 10−56) and was, therefore, highly statistically significant. The three reported start sites for the US1.5 protein lie in motifs 5, 7, and 8.52–54 Motifs 5 and 9 each contain one of the nuclear localization signals, and motif 8 contains a putative nucleotidylation site.49 The consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site51 (Y193) mapped to motif 1. In the Old World simian virus group (e.g., SA8), only motifs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 were conserved; thus, MEME analysis can clearly be used to distinguish simian α-herpesviruses from human viruses. The avian and varicellovirus groups are characterized by the presence of motif 6. The presence of motif 10 was variable; it was present in GaHV-2 and VZV but not in the duck enteritis virus.

Figure 4.

MEME analysis for conserved motifs within the α-herpesvirus α22 protein. Motif detection was limited to a phylogenetically relevant n = 10. The sequence of each of the motifs is presented; the larger the letter, the greater the conservation.

Figure 5.

Map of MEME analysis for conserved motifs in the α-herpesvirus α22 protein. The motifs are numbered 1 through 10 and are color coded for visualization. Motifs discovered in the summary MEME analysis were conservatively excluded to limit the number of false-positive motif placements. The location of the predicted globular domain of the protein is denoted by the green hatched bars. Note that motif 1 is located in the putative globular domain in all the groups.

When the GlobPlot2 program was used to examine potential folding of the HSV-1 strain 17 US1 protein (Fig. 5), we found that only the central portion of the protein could be folded into a putative globular domain. This region overlapped motif 1 in all the α-herpesvirus α22 proteins. These results are consistent with the central portion of the α22 protein as a core conserved region.

Discussion

The HSV-1 US1 gene encodes an immediate early (α) protein that carries out a number of functions in infected cells and is clearly a host range virulence determinant.25,26,34,75–77 We previously identified two sequence changes in the α22 protein of the avirulent strains OD4, S34A, and Y116C25,26,59 that, when reverted to wild type, conferred the ability to cause severe keratitis in a mouse model. At that time, only the strain 17 sequence was available for comparison. In this study, we sequenced the US1 gene from six low-passage ocular HSV-1 isolates as well as KOS and F and used these new sequence data to carry out a bioinformatic analysis and to determine the sequence variability in the α-herpesvirus US1 homologs. When we analyzed the amino acid sequence variability in the HSV-1 α22 protein, we found several differences between the strains. Sequence variability was highest in the amino-terminal third of the protein. Multiple functions have been mapped to the carboxyl-terminal portion, including modification of Pol II.46,57 Thus, the clustering of several functions in the carboxyl-terminal half of the protein may account for the sequence conservation in this region.

A second protein, US1.5, which plays a role in the host range of the virus, is involved in optimal expression of ICP0 and γ-genes and is distributed differently in infected cells compared with α22.56,78 It is encoded within the US1 gene, and is identical with the carboxyl terminus of the α22 protein.54,78 Thus, the clustering of multiple functions in the C-terminal half of the protein and the presence of an overlapping protein could also explain the higher sequence conservation in this part of the α22 protein compared with the amino-terminal third. The potential effects of sequence variability on the function, or functions, of the US1.5 protein depend on the start site. Currently, three start sites—M90, M147, and M171—have been reported for the US1.5 protein, and it is unclear whether all three sites are used or whether the start site differs between strains.52–54 Based on the reduced variability in the C-terminal half of the sequence, if US1.5 begins at residue 147 or 171,52,53 the variability would have less effect. However, if translation of US1.5 begins as residue 90,54 then the sequence variability would be greater and may affect the function of the US1.5 protein. Additional studies are clearly required.

The S34A and Y116C changes in OD4 had previously been shown to be partially responsible for the attenuation of strain OD4 in ocular infections.25,26 Six of the strains—KOS, OD4, TFT401, CJ994, R-15, and HF-10—had the S34A sequence change. However, both changes were required for the loss of virulence in strain OD4; thus, the presence of only S34A would not be expected to change ocular virulence. However, KOS had both changes and causes keratitis.59 There are several possible explanations for this apparent discrepancy. One we currently favor is related to observations that the α22 protein interacts with multiple viral and cellular proteins (see Introduction) and that its role in virulence very likely depends on at least some of these interactions. This may be an example of epistasis or, more specifically, sign epistasis, in which the phenotype of a particular mutation depends on the context in which it is expressed.79 Sequence changes in other KOS proteins could compensate for the US1 changes and maintain virulence. The KOS US1 protein also has an additional sequence difference compared to OD4 (A10V), and this could be compensatory. Additional studies with KOS and OD4 are needed to address this issue.

The HSV-1 strains could be separated into three groups or clades. Previous phylogenetic analyses using the HSV-1 gC, gG, gE, and gI genes also indicated that there were three clades.73,74 However, the clades identified using the gC, gG, gE, and gI genes were not the same as those identified using the US1 gene. For example, strains F and 17 were in the same clade based on US1 sequences, but they sorted in different clades based on the gE/gI sequences. The differences in clade structure seen when analyzing single genes or a small subset of genes point to a weakness with this approach because it may bias the actual genetic relationships between the strains. The most likely explanation is that this is the result of recombination events between strains, but further work is needed to confirm this.

The MEME analysis, which identifies phylogenetically useful motifs, revealed a number of interesting structural features in the α22 protein. First, unique patterns of motifs were identified for the human viruses, Old World monkey viruses, and the varicella viruses. For example, motifs 4, 7, and 9 were unique to HSV-1 and HSV-HG52, which would be expected given their close evolutionary relationship. Some motifs are predominantly cationic whereas others are primarily anionic. Several of the motifs were hydrophobic. Hydrophobic residues tend to be conserved in regions involved in folding and the maintenance of the tertiary structure, suggesting that these motifs might be important for stabilizing the α22 protein structure. As revealed in Figure 4, each of the motifs has several highly conserved residues, and these motifs can now serve as the focus of mutational studies to determine structure-function relationships in the α22 protein.

The analysis also identified a motif (motif 1) that was conserved in all α-herpesvirus US1 homologs. Motif 1, which has 63 residues, was contained within a larger region previously identified as conserved across the α-herpesvirus subfamily.57,80 Thus, our analysis more precisely defines this core conserved sequence. We identified several residues using the ClustalW alignment program (Supplementary Fig. S1, http://www.iovs.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1167/iovs.10-7032/-/DCSupplemental) that are absolutely conserved in the US1 homologs analyzed, including W187, N198, F202, R219, G229, R234, W240, L255, R256, and D317, which were located in the predicted globular domain (Fig. 6). The conservation of residues within this region would be consistent with it functioning as a conserved core or scaffold for variable amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains.

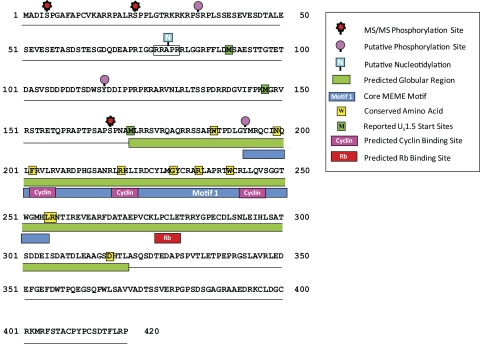

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the HSV-1 α22 protein showing predicted and confirmed phosphorylation sites (unpublished data, 2010), the location of MEME motif 1, structural features and consensus sequence motifs, predicted functional regions, and amino acid residues that are conserved in all the strains analyzed. Note that we have shown all three of the reported start sites for the US1.5 protein. The legend denotes features that have been experimentally confirmed versus those that are predicted.

When we applied the protein folding program GlobPlot2 to the HSV-1 α22 sequence, we found that only the very central region was predicted to fold into a globular domain and that motif 1 was centered in this region. This behavior is characteristic of proteins that can adopt alternative conformations that are regulated by posttranslational modification such as phosphorylation.81 The fact that the α22 protein has multiple functions, is present in at least seven or eight isoforms in infected cells, and is phosphorylated would be consistent with such behavior. We propose that the US1 protein consists of a central core scaffold region centered on motif 1 that has amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains that can adopt different conformations, depending on specific posttranslational modifications. These different conformers would then carry out specific functions.

As shown in Figure 6, we compiled the available data on the structural features of the HSV-1 α22 protein. This analysis reveals a number of important features and serves as a guide for site-directed mutagenesis studies. We included both predicted and confirmed modification sites, recognizing that additional studies using physical methods are needed to confirm modification sites. Note that the phosphorylation of serines 5, 22, and 167 have been confirmed using ms/ms (Hermann Bultmann and Curtis Brandt, unpublished data, 2010). Predicted cyclin and Rb protein binding sites were identified and reside in the central globular region. The presence of cyclin binding sites is consistent with previous reports that α22 interacts with CDK9.27,82

In summary, for the first time, we show that there is significant sequence variability in the HSV-1 α22 protein and that most of the variability lies in the amino-terminal third of the protein. We have also identified 10 conserved residues in the protein and that a core 63 amino acid sequence is located in the central part of the α22 protein. This information is critical for designing targeted mutational studies of the structure and function of the α22 protein and its role in virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Chandler for providing the ocular viral isolates.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY07336 (CRB), P30 EY016665, and P2PRRR016478 (DWD); National Center for Research Resources Grant P20 RR-015564 (DWD); a Research to Prevent Blindness Senior Scientist Award (CRB); and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. to the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Disclosure: A.W. Kolb, None; T.R. Schmidt, None; D.W. Dyer, None; C.R. Brandt, None

References

- 1. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex viruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM. eds. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:2297–2342 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhattacharjee PS, Neumann DM, Foster TP, et al. Effect of human apolipoprotein E genotype on the pathogenesis of experimental ocular HSV-1. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:122–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burgos JS, Ramirez C, Sastre I, Valdivieso F. Effect of apolipoprotein E on the cerebral load of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA. J Virol. 2006;80:5383–5387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han X, Lundberg P, Tanamachi B, Openshaw H, Longmate J, Cantin E. Gender influences herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in normal and gamma interferon-mutant mice. J Virol. 2001;75:3048–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kastrukoff LF, Lau AS, Puterman ML. Genetics of natural resistance to herpes simplex virus type 1 latent infection of the peripheral nervous system in mice. J Gen Virol. 1986;67(pt 4):613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez C. Genetics of natural resistance to herpesvirus infections in mice. Nature. 1975;258:152–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lundberg P, Welander P, Openshaw H, et al. A locus on mouse chromosome 6 that determines resistance to herpes simplex virus also influences reactivation, while an unlinked locus augments resistance of female mice. J Virol. 2003;77:11661–11673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snyder A, Polcicova K, Johnson DC. Herpes simplex virus gE/gI and US9 proteins promote transport of both capsids and virion glycoproteins in neuronal axons. J Virol. 2008;82:10613–10624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stulting RD, Kindle JC, Nahmias AJ. Patterns of herpes simplex keratitis in inbred mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:1360–1367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang SY, Jouanguy E, Ugolini S, et al. TLR3 deficiency in patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. Science. 2007;317:1522–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koelle DM, Corey L. Recent progress in herpes simplex virus immunobiology and vaccine research. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:96–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollara G, Katz DR, Chain BM. The host response to herpes simplex virus infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sørensen LN, Reinert LS, Malmgaard L, Bartholdy C, Thomsen AR, Paludan SR. TLR2 and TLR9 synergistically control herpes simplex virus infection in the brain. J Immunol. 2008;181:8604–8612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doymaz MZ, Rouse BT. Immunopathology of herpes simplex virus infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;179:121–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Streilein JW, Dana MR, Ksander BR. Immunity causing blindness: five different paths to herpes stromal keratitis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas J, Rouse BT. Immunopathogenesis of herpetic ocular disease. Immunol Res. 1997;16:375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brandt CR. Virulence genes in herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29:103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brandt CR. The role of viral and host genes in corneal infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:607–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McGeoch DJ, Dalrymple MA, Davison AJ, et al. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(pt 7):1531–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McGeoch DJ, Dolan A, Donald S, Brauer DH. Complete DNA sequence of the short repeat region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:1727–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGeoch DJ, Dolan A, Donald S, Rixon FJ. Sequence determination and genetic content of the short unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perry LJ, McGeoch DJ. The DNA dequences of the long repeat region and adjoining parts of the long unique region in the genome of herpes-simplex virus type-1. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2831–2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szpara ML, Parsons L, Enquist LW. Sequence variability in clinical and laboratory isolates of herpes simplex virus 1 reveals new mutations. J Virol. 2010;84:5303–5313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brandt CR, Kolb AW. Tyrosine 116 of the herpes simplex virus type 1 IEα22 protein is an ocular virulence determinant and potential phosphorylation site. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4601–4607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brandt CR, Kolb AW, Shah DD, et al. Multiple determinants contribute to the virulence of HSV ocular and CNS infection and identification of serine 34 of the US1 gene as an ocular disease determinant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2657–2668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Durand LO, Advani SJ, Poon AP, Roizman B. The carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II is phosphorylated by a complex containing cdk9 and infected-cell protein 22 of herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 2005;79:6757–6762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fraser KA, Rice SA. Herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP22 triggers loss of serine 2-phosphorylated RNA polymerase II. J Virol. 2007;81:5091–5101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenkins HL, Spencer CA. RNA polymerase II holoenzyme modifications accompany transcription reprogramming in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected cells. J Virol. 2001;75:9872–9884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Long MC, Leong V, Schaffer PA, Spencer CA, Rice SA. ICP22 and the UL13 protein kinase are both required for herpes simplex virus-induced modification of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II. J Virol. 1999;73:5593–5604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rice SA, Long MC, Lam V, Schaffer PA, Spencer CA. Herpes-simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP22 is required for viral modification of host RNA-polymerase-II and establishment of the normal viral transcription program. J Virol. 1995;69:5550–5559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Markovitz NS, Roizman B. Small dense nuclear bodies are the site of localization of herpes simplex virus 1 U(L)3 and U(L)4 proteins and of ICP22 only when the latter protein is present. J Virol. 2000;74:523–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ng TI, Chang YE, Roizman B. Infected cell protein 22 of herpes simplex virus 1 regulates the expression of virion host shutoff gene U(L)41. Virology. 1997;234:226–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poffenberger KL, Raichlen PE, Herman RC. In vitro characterization of a herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 deletion mutant. Virus Genes. 1993;7:171–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Poon APW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 ICP22 regulates the accumulation of a shorter mRNA and of a truncated U(S)3 protein kinase that exhibits altered functions. J Virol. 2005;79:8470–8479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Purves FC, Ogle WO, Roizman B. Processing of the herpes simplex virus regulatory protein alpha 22 mediated by the UL13 protein kinase determines the accumulation of a subset of alpha and gamma mRNAs and proteins in infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6701–6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Orlando JS, Balliet JW, Kushnir AS, et al. ICP22 is required for wild-type composition and infectivity of herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J Virol. 2006b;80:9381–9390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bowman JJ, Orlando JS, Davido DJ, Kushnir AS, Schaffer PA. Transient expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 represses viral promoter activity and complements the replication of an ICP22 null virus. J Virol. 2009a;83:8733–8743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prod'hon C, Machuca I, Berthomme H, Epstein A, Jacquemont B. Characterization of regulatory functions of the HSV-1 immediate-early protein ICP22. Virology. 1996;226:393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barcy S, Corey L. Herpes simplex inhibits the capacity of lymphoblastoid B cell lines to stimulate CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6242–6249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bruni R, Fineschi B, Ogle WO, Roizman B. A novel cellular protein, p60, interacting with both herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory proteins ICP22 and ICP0 is modified in a cell-type-specific manner and Is recruited to the nucleus after infection. J Virol. 1999;73:3810–3817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bruni R, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory protein ICP22 interacts with a new cell cycle-regulated factor and accumulates in a cell cycle-dependent fashion in infected cells. J Virol. 1998;72:8525–8531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jahedi S, Markovitz NS, Filatov F, Roizman B. Colocalization of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL4 protein with infected cell protein 22 in small, dense nuclear structures formed prior to onset of DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1999;73:5132–5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leopardi R, Ward PL, Ogle WO, Roizman B. Association of herpes simplex virus regulatory protein ICP22 with transcriptional complexes containing EAP, ICP4, RNA polymerase II, and viral DNA requires posttranslational modification by the U(L)13 proteinkinase. J Virol. 1997;71:1133–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith-Donald BA, Roizman B. The interaction of herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory protein ICP22 with the cdc25C phosphatase is enabled in vitro by viral protein kinases US3 and UL13. J Virol. 2008;82:4533–4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Orlando JS, Astor TL, Rundle SA, Schaffer PA. The products of the herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early US1/US1.5 genes downregulate levels of S-phase-specific cyclins and facilitate virus replication in S-phase Vero cells. J Virol. 2006a;80:4005–4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blaho JA, Mitchell C, Roizman B. Guanylylation and adenylylation of the alpha regulatory proteins of herpes simplex virus require a viral beta or gamma function. J Virol. 1993;67:3891–3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blaho JA, Zong CS, Mortimer KA. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP22 and a cellular protein which shares antigenic determinants with ICP22. J Virol. 1997;71:9828–9832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mitchell C, Blaho JA, McCormick AL, Roizman B. The nucleotidylylation of herpes simplex virus 1 regulatory protein alpha22 by human casein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25394–25400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mitchell C, Blaho JA, Roizman B. Casein kinase II specifically nucleotidylylates in vitro the amino acid sequence of the protein encoded by the alpha 22 gene of herpes simplex virus 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11864–11868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Toole JM, Aubert M, Kotsakis A, Blaho JA. Mutation of the protein tyrosine kinase consensus site in the herpes simplex virus 1 alpha22 gene alters ICP22 posttranslational modification. Virology. 2003;305:153–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Poon APW, Ogle WO, Roizman B. Posttranslational processing of infected cell protein 22 mediated by viral protein kinases is sensitive to amino acid substitutions at distant sites and can be cell-type specific. J Virol. 2000;74:11210–11214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ogle WO, Roizman B. Functional anatomy of herpes simplex virus 1 overlapping genes encoding infected-cell protein 22 and US1.5 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:4305–4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bowman JJ, Schaffer PA. Origin of expression of the herpes simplex virus type 1 protein U(S)1.5. J Virol. 2009b;83:9183–9194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hagglund R, Munger J, Poon APW, Roizman B. US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus 1 blocks caspase 3 activation induced by the products of US1.5 and UL13 genes and modulates expression of transduced US1.5 open reading frame in a cell type-specific manner. J Virol. 2002;76:743–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cun W, Hong M, Liu LD, Dong CH, Luo J, Li QH. Structural and functional characterization of herpes simplex virus 1 immediate-early protein infected-cell protein 22. J Biochem. 2006;140:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bastian TW, Rice SA. Identification of sequences in herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 that influence RNA polymerase II modification and viral late gene expression. J Virol. 2009;83:128–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bastian TW, Livingston CM, Weller SK, Rice SA. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP22 is required for VICE domain formation during productive viral infection. J Virol. 2010;84:2384–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grau DR, Visalli RJ, Brandt CR. Herpes simplex virus stromal keratitis is not titer-dependent and does not correlate with neurovirulence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:2474–2480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brandt CR, Grau DR. Mixed infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 generates recombinants with increased ocular and neurovirulence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2214–2223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sedarati F, Stevens JG. Biological basis for virulence of three strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1987;68(pt 9):2389–2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kintner RL, Brandt CR. Rapid small-scale isolation of herpes simplex virus DNA. J Virol Methods. 1994;48:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method- a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies—an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bailey TL, Elkan C. Unsupervised learning of multiple motifs in biopolymers using expectation maximization. Machine Learning. 1995;21:51–80 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Korber B. Computational analysis of HIV molecular sequences. In: Rodrigo AG, Learn GH. eds. HIV Signature and Sequence Variation Analysis. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000;55–72 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Linding R, Russell RB, Neduva V, Gibson TJ. GlobPlot: exploring protein sequences for globularity and disorder. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3701–3708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Puntervoll P, Linding R, Gemund C, et al. ELM server: a new resource for investigating short functional sites in modular eukaryotic proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3625–3630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Trybala E, Roth A, Johansson M, et al. Glycosaminoglycan-binding ability is a feature of wild-type strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology. 2002;302:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Norberg P, Bergstrom T, Rekabdar E, Lindh M, Lijeqvist J. Phylogenetic analysis of clinical herpes simplex virus type 1 isolates identified three genetic groups and recombinant viruses. J Virol. 2004;78:10755–10764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Poffenberger KL, Idowu AD, Fraser-Smith EB, Raichlen PE, Herman RC. A herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 deletion mutant is altered for virulence and latency in vivo. Arch Virol. 1994;139:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sears AE, Halliburton IW, Meignier B, Silver S, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 mutant deleted in the alpha 22 gene: growth and gene expression in permissive and restrictive cells and establishment of latency in mice. J Virol. 1985a;55:338–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sears AE, Roizman B. Cell-specific selection of mutants of a herpes simplex virus recombinant carrying deletions. Virology. 1985b;145:176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carter KL, Roizman B. The promoter and transcriptional unit of a novel herpes simplex virus 1 alpha gene are contained in, and encode a protein in frame with, the open reading frame of the alpha 22 gene. J Virol. 1996;70:172–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Phillips PC. Epistasis—the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:855–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schwyzer M, Wirth UV, Vogt B, Fraefel C. BICP22 of bovine herpesvirus 1 is encoded by a spliced 1.7 kb RNA which exhibits immediate early and late transcription kinetics. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(pt 7):1703–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Redfield C. Using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study molten globule states of proteins. Methods. 2004;34:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Durand LO, Roizman B. Role of cdk9 in the optimization of expression of the genes regulated by ICP22 of Herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol. 2008;82:10591–10599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.