HDL pathway genes LIPC and ABCA1 are associated with intermediate drusen, large drusen, and advanced AMD independent of age, sex, education, smoking, body mass index, antioxidant treatment, and other known genetic variants.

Abstract

Purpose.

Intermediate and large drusen usually precede advanced age-related macular degeneration (AMD). There is little information about which genes influence drusen accumulation. Discovery of genetic variants associated with drusen may lead to prevention and treatments of AMD in its early stages.

Methods.

A total of 3066 subjects were evaluated on the basis of ocular examinations and fundus photography and categorized as control (n = 221), intermediate drusen (n = 814), large drusen (n = 949), or advanced AMD (n = 1082). SNPs in the previously identified CFH, C2, C3, CFB, CFI, APOE, and ARMS2/HTRA1 genes/regions and the novel genes LIPC, CETP, and ABCA1 in the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol pathway were genotyped. Associations between stage of AMD and SNPs were assessed using logistic regression.

Results.

Controlling for age, sex, education, smoking, body mass index, and antioxidant treatment, the number of minor (T) alleles of the genes LIPC and ABCA1 were significantly associated with a reduced risk of intermediate drusen (LIPC [P trend = 0.045], ABCA1 [P = 4.4 × 10−3]), large drusen (LIPC [P = 0.041], ABCA1 [P = 7.7 × 10−4]), and advanced AMD (LIPC [P = 1.8 × 10−3], ABCA1 [P = 3 × 10−4]). After further adjustment for known genetic factors, the protective effect of the TT genotype was significant for intermediate drusen (LIPC [odds ratio (OR), 0.56; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.33–0.94], ABCA1 [OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.27–0.85]), large drusen (LIPC [OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.34–0.98)], ABCA1 [OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.23–0.74)]), and advanced AMD (LIPC [OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.21–0.74)], ABCA1 [OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17–0.71)]). CFH, C3, C2, and ARMS2/HTRA1 were associated with large drusen and advanced AMD.

Conclusions.

LIPC and ABCA1 are related to intermediate and large drusen, as well as advanced AMD. CFH, C3, C2, and ARMS2/HTRA1 are associated with large drusen and advanced AMD. Genes may have varying effects on different stages of AMD.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common, complex, chronic eye disease.1 As a leading cause of vision loss in people older than 60 years, AMD currently affects more than 1.75 million individuals in the United States. This number is expected to increase by more than 50% to 3 million in 2020 due to aging of the population.2 The most severe visual loss due to AMD occurs when the disease progresses to one of the two advanced forms: geographic atrophy (GA) or choroidal neovascularization (NV).3 GA features well-demarcated borders of atrophy that develop as the macular neurosensory cells slowly degenerate. NV is characterized by the creation of new blood vessels beneath the retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) layer of the retina, which cause bleeding, subretinal fluid, and scarring of the macula. Although GA and NV are pathophysiologically and clinically distinct,4 they have one common hallmark, which is drusen between the RPE and Bruch's membrane.5 Drusen are extracellular deposits composed mainly of lipids and proteins, including esterified and unesterified cholesterol, apolipoproteins, vitronectin, amyloid, complement factor H, and complement component C3.6–11 Although the mechanism of drusen initiation and development is unclear, it has been hypothesized that age-related lipid accumulation in Bruch's membrane may induce early physiologic changes and lesions in the RPE.12 These age-related lipid accumulations may then interact with other lipids, local ligands, or additional secreted self-aggregating proteins, such as the complement complex, to manifest as clinically detectable drusen.5,12

Genetic and environmental factors both contribute to the risk of developing AMD by various proportions during the early, intermediate, and advanced stages of this disease.13 Cigarette smoking and higher body mass index (BMI) increase the risk of advanced AMD and its progression14–19 and also modify genetic susceptibility.18,20

At least two independent variants in the complement factor H (CFH) gene are associated with advanced AMD.21–26 Variants of several other genes in the alternative complement pathway, including CFB/C2,24,27 C3,28,29 and CFI,30 also contribute to the risk of developing advanced AMD. The ARMS2/HTRA1 region on chromosome 10 confers a high risk of advanced AMD and is not in the complement pathway.31,32 Both CFH and the ARMS2/HTRA1 region have been related to large, soft, or cuticular drusen.33–36 Recently, in a well-powered, genome-wide association study (GWAS), we reported that another noncomplement gene, a variant in the hepatic lipase gene LIPC, which regulates triglyceride hydrolysis and plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) levels,37,38 decreases the risk of advanced AMD.39,40 This finding unveils the involvement of proteins described in the plasma HDL pathway in the pathogenesis of AMD. Other genes in the HDL pathway, including CETP and ABCA1, may also be involved in the etiology of AMD.39,40 The APOE gene, a widely expressed cholesterol transporter, has been shown to be associated with AMD in some studies, but results are inconsistent.41–44 Although it is well known that lipids are major components of drusen,11,12 the effects of genetic variants in the recently identified HDL pathway genes on drusen development have not been previously reported. In this study, we analyzed the effects of HDL and LDL genes, ARMS2/HTRA1 and known genes in the complement pathway on intermediate and large drusen, as well as GA and NV, to investigate and compare their roles in these different stages of AMD.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Phenotypes for 3066 Caucasian subjects with DNA specimens in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) were evaluated. Each eye of a subject was categorized by using the Clinical Age-Related Maculopathy Staging System (CARMS) grades45 based on the longitudinal records of ocular examination and fundus photography. Eyes were assigned to neovascular AMD (grade 5) if there was a history of any of the following: hemorrhagic retinal detachment, hemorrhage under the retina or retinal pigment epithelium, or subretinal fibrosis. Eyes with a record of GA, either in the center grid or anywhere within the grid and without any record of hemorrhage, were assigned to a grade 4. For eyes without any of the above signs of advanced AMD, grades were determined by the highest drusen category score43,44 among the longitudinal records. Eyes with large, soft drusen (≥125μm) and eyes with intermediate drusen (63–124μm) were assigned to grades 3 and 2, respectively. The control group (grade 1) included eyes with either no drusen or only a few small drusen (<63μm). The final grade for each subject was based on the eye with the most advanced stage of AMD. This research complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

SNP Selection

We assessed variants in lipoprotein metabolism genes, including a functional variant (rs10468017) in the hepatic lipase (LIPC) gene on 15q22, which was associated with advanced AMD with genome-wide significance (P = 1.34 × 10−8) in our previous GWAS45; SNP rs1883025 in the ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) gene on 9q31; and SNP rs3764261 in the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) gene on 16q21, which had suggestive associations with advanced AMD in previous GWAS39,40 and haplotypes in the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene which have been reported to be associated with AMD.41,42 We also genotyped a nonsynonymous SNP rs10490924 in the ARMS2/HTRA1 q26 region of chromosome 10 which is associated with advanced AMD but not known to be related to the complement pathway.31,32,47,48 In addition, five known risk variants associated with advanced AMD in complement genes were genotyped: SNP rs1061170 in exon 9 of the CFH gene on 1q31, which results in a substitution of histidine for tyrosine (Y402H) in the protein sequence of CFH; SNP rs9332739 in the complement component 2 (C2) gene, which results in the amino acid change E318D in exon 7; SNP rs641153 in the complement factor B (CFB) gene, which results in an amino acid change at R32Q; SNP rs2230199 in the complement component 3 (C3) gene, which results in an amino acid change at R102G in exon 3; and SNP rs10033900 in complement factor I (CFI) on chromosome 4.21–32,47,48

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from blood samples of the participants. SNPs in the CFH, ARMS2/HTRA1, C2, C3, CFB, and CFI genes were genotyped at the Broad Institute Center for Genotyping and Analysis (iPLEX assay; Sequenom, San Diego, CA; http://www.sequenom.com/Genetic-Analysis/Applications/iPLEX-Genotyping/iPLEX-Overview.aspx). For SNPs not compatible with the assay, such as APOE, and other SNPs newly reported to be associated with advanced AMD, including LIPC, CETP, and ABCA1 genes/regions, DNA samples were genotyped (TaqMan assay, with sequence detection on the Prism 7900; ABI, Foster City, CA; https://products.appliedbiosystems.com/ab/en/US/adirect/ab?cmd=catNavigate2&catID=601283).

We implemented stringent quality control criteria for each SNP in our dataset. All the SNPs had a greater than 99% genotype call rate. The rates for missing SNPs genotyped on the two platforms (iPLEX and TaqMan) were similar. None of the SNPs was significant (P < 10−3) in the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test or (P < 10−3) in the differential missing tests between cases and controls. All quality control steps were performed using PLINK.49

Statistical Analysis

To analyze the genetic effects on different stages of AMD, we classified subjects into case and control groups by their worse eye grades. Subjects with a worse eye grade of 1 were used as the control group in all models. The allele frequencies of each SNP in the two drusen groups (intermediate drusen or large drusen; grade 2 or 3) and the allele frequencies in the advanced AMD group (GA or NV; grade 4 or 5) were compared with the allele frequencies in the control group. We tested associations between SNPs and each disease stage by logistic regression (SAS ver. 9.2; SAS, Cary, NC). SNPs were coded as 0, 1, and 2 by the number of risk alleles in the tests for linear trend. Demographic and behavioral covariates, including age (continuous), sex, education (less than or equal to high school or more than high school), smoking (never, past, or current), BMI (<25, 25–29.9, and ≥30), and randomized antioxidant treatment in AREDS were included in the models. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to further adjust for the known genetic factors, in addition to the demographic and behavioral factors. To estimate the effects of specific genotypes of LIPC and ABCA1 variants, we applied polytomous logistic regression in multivariate models.

Results

Among the 3066 Caucasian participants, there were 221 controls with no drusen or only a few small drusen and 814 subjects with intermediate drusen, 949 with large soft drusen, 259 with GA, and 823 with NV. Subjects with GA or NV were classified as having advanced AMD. For each SNP evaluated, the number of participants included in the analyses varied slightly, depending on the genotype call rates, which were all greater than 99% in this study. The distributions of demographic and behavioral characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1. Numbers in tables may not equal totals due to missing information. Older subjects, those who smoked or had less than a high school education were more likely to have advanced AMD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects in Each Phenotype Group

| Control | Drusen |

Advanced AMD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate | Large | GA | NV | ||

| Subjects, n | 221 | 814 | 949 | 259 | 823 |

| Mean age ± SD, y | 77.0 ± 4.6 | 78.1 ± 4.2 | 78.9 ± 4.9 | 79.5 ± 5.5 | 80.7 ± 5.1 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 116 (52) | 463 (57) | 548 (58) | 129 (50) | 477 (58) |

| Male | 105 (48) | 351 (43) | 401 (42) | 130 (50) | 346 (42) |

| Education | |||||

| >High school | 155 (70) | 587 (72) | 656 (69) | 163 (63) | 473 (57) |

| ≤High school | 66 (30) | 226 (28) | 292 (31) | 96 (37) | 350 (43) |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 105 (47) | 438 (54) | 473 (50) | 108 (42) | 321 (39) |

| Past | 101 (46) | 342 (42) | 442 (46) | 134 (52) | 417 (51) |

| Current | 15 (7) | 34 (4) | 34 (4) | 17 (6) | 85 (10) |

| BMI | |||||

| <25 | 65 (31) | 280 (35) | 339 (37) | 78 (31) | 220 (27) |

| 25–29.9 | 88 (41) | 337 (43) | 403 (44) | 105 (41) | 345 (43) |

| ≥30 | 60 (28) | 174 (22) | 179 (19) | 70 (28) | 240 (30) |

| Antioxidants | |||||

| No | 128 (58) | 418 (51) | 442 (47) | 136 (53) | 411 (50) |

| Yes | 93 (42) | 396 (49) | 507 (53) | 123 (47) | 412 (50) |

Data are expressed as the number (percentage of total group), unless otherwise noted.

Table 2 shows the genotype frequencies of variants in each gene separately for the controls and each case group, and also P values for tests for linear trend for the number of effective alleles for each SNP. With adjustment for demographic and behavioral factors, the associations between each SNP and large drusen for CFH (P = 9.8 × 10−3), ARMS2/HTRA1 (P = 6.3 × 10−5), ABCA1 (P = 7.7 × 10−4), and LIPC (P = 0.041) were significant. However, only ABCA1 (P = 4.4 × 10−3) and LIPC (P = 0.045) were significantly related to intermediate drusen. Associations between advanced AMD and CFH (rs1061170, P = 1.0 × 10−14), C2 (rs9332739, P = 1.2 × 10−4), C3 (rs2230199, P = 1.1 × 10−4), CFB (rs641153, P = 1.2 × 10−5), CFI (rs10033900, P = 8.0 × 10−3), and ARMS2/HTRA1 (rs10490924 P = 2.7 × 10−18) were confirmed. The genes LIPC (rs10468017 P = 1.8 × 10−3) and ABCA1 (rs1883025 P = 3.0 × 10−4) in the cholesterol/lipoprotein pathways were also significantly associated with advanced AMD. Associations between advanced AMD and CETP (rs3764261, P = 0.09) and APOE (P = 0.06) were not significant, but were in the same direction as previously reported.

Table 2.

Associations between Drusen and Advanced AMD and Genetic Factors in Single SNP Models

| SNP (Gene) | Controls None, ≤63 μm n (%) | Drusen |

Advanced AMD |

EA | Intermediate Drusen OR (95% CI) P* | Large Drusen OR (95% CI) P* | Advanced AMD OR (95% CI) P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63–124 μm n (%) | ≥125 μm n (%) | GA n (%) | NV n (%) | ||||||

| Subjects, n | 221 | 814 | 949 | 259 | 823 | ||||

| rs10468017 LIPC | |||||||||

| C C | 98 (45) | 414 (51) | 473 (50) | 148 (58) | 432 (53) | T | 0.79 (0.62–0.99) | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) |

| T C | 93 (43) | 326 (41) | 396 (42) | 91 (35) | 333 (41) | P = 0.045 | P = 0.041 | P = 1.8 × 10−3 | |

| T T | 27 (12) | 61 (8) | 73 (8) | 17 (7) | 46 (6) | ||||

| rs1883025 ABCA1 | |||||||||

| C C | 99 (46) | 440 (55) | 548 (58) | 153 (60) | 472 (58) | T | 0.7 (0.55–0.9) | 0.66 (0.52–0.84) | 0.63 (0.5–0.81) |

| C T | 95 (44) | 318 (39) | 337 (36) | 87 (34) | 315 (38) | P = 4.4 × 10−3 | P = 7.7 × 10−4 | P = 3.0 × 10−4 | |

| T T | 23 (10) | 48 (6) | 58 (6) | 16 (6) | 34 (4) | ||||

| rs3764261 CETP | |||||||||

| C C | 102 (47) | 358 (44) | 413 (44) | 113 (44) | 336 (41) | A | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 1.1 (0.87–1.4) | 1.22 (0.97–1.55) |

| A C | 98 (45) | 366 (45) | 428 (45) | 115 (45) | 359 (44) | P = 0.37 | P = 0.42 | P = 0.09 | |

| A A | 18 (8) | 85 (11) | 102 (11) | 28 (11) | 125 (15) | ||||

| APOE | |||||||||

| E2/E3 | 160 (73) | 620 (77) | 732 (78) | 210 (82) | 660 (80) | E4 | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.89 (0.62–1.27) | 0.71 (0.49–1.02) |

| E4 | 58 (27) | 185 (23) | 208 (22) | 45 (18) | 160 (20) | P = 0.47 | P = 0.51 | P = 0.06 | |

| rs1061170 CFH | |||||||||

| T T | 83 (38) | 336 (42) | 307 (32) | 57 (22) | 125 (15) | C | 0.98 (0.78–1.22) | 1.34 (1.07–1.67) | 2.45 (1.96–3.08) |

| C T | 106 (49) | 366 (45) | 442 (47) | 107 (42) | 368 (45) | P = 0.84 | P = 9.8 × 10−3 | P = 1.0 × 10−14 | |

| C C | 27 (13) | 108 (13) | 119 (21) | 94 (36) | 322 (40) | ||||

| rs10490924 ARMS2/HTRA1 | |||||||||

| G G | 147 (68) | 523 (65) | 505 (53) | 104 (40) | 251 (31) | T | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.76 (1.33–2.32) | 3.44 (2.61–4.55) |

| T G | 65 (30) | 254 (31) | 362 (39) | 114 (44) | 395 (48) | P = 0.21 | P = 6.3 × 10−5 | P = 2.7 × 10−18 | |

| T T | 5 (2) | 33 (4) | 81 (9) | 41 (16) | 171 (21) | ||||

| rs9332739 C2 | |||||||||

| GG | 193 (89) | 737 (91) | 876 (92) | 247 (96) | 784 (96) | C | 0.75 (0.45–1.25) | 0.63 (0.38–1.05) | 0.32 (0.18–0.57) |

| CG/CC | 23 (11) | 73 (9) | 72 (8) | 11 (4) | 30 (4) | P = 0.27 | P = 0.074 | P = 1.2 × 10−4 | |

| rs2230199 C3 | |||||||||

| C C | 140 (65) | 506 (63) | 539 (57) | 129 (50) | 397 (49) | G | 1.04 (0.79–1.38) | 1.31 (0.99–1.74) | 1.72 (1.31–2.25) |

| G C | 68 (31) | 273 (34) | 363 (38) | 106 (41) | 351 (43) | P = 0.77 | P = 0.056 | P = 1.1 × 10−4 | |

| G G | 8 (4) | 28 (3) | 45 (5) | 24 (9) | 67 (8) | T | |||

| rs641153 CFB | |||||||||

| C C | 173 (80) | 673 (83) | 806 (85) | 230 (89) | 750 (92) | 0.83 (0.55–1.23) | 0.69 (0.46–1.03) | 0.38 (0.24–0.58) | |

| CT/TT | 43 (20) | 137 (17) | 142 (15) | 28 (11) | 64 (8) | P = 0.35 | P = 0.069 | P = 1.2 × 10−5 | |

| rs10033900 CFI | |||||||||

| C C | 65 (30) | 225 (28) | 235 (25) | 56 (22) | 187 (23) | T | 1.14 (0.92–1.42) | 1.15 (0.92–1.44) | 1.35 (1.08–1.68) |

| C T | 107 (50) | 378 (47) | 488 (51) | 121 (47) | 400 (49) | P = 0.22 | P = 0.21 | P = 8.0 × 10−3 | |

| T T | 44 (20) | 207 (25) | 225 (24) | 81 (31) | 227 (28) | ||||

EA, effective allele of which the genetic effect were shown for each SNP.

Test of linear trend for single SNP additive model adjusted for age, sex, education (≤high school vs. >high school), smoking (never, past, current), BMI (<25, 25–29.9, 30+), and antioxidant treatment. Significant results (P < 0.05) are shown in bold.

To evaluate whether the associations between drusen and advanced AMD are independent of other genetic factors, we performed multivariate logistic analysis using the demographic and behavioral risk factors for AMD shown in Table 1, plus all the genetic factors (Table 3). The relationship between the case groups and the number of effective alleles was assessed. Only the two HDL genes LIPC (P = 0.04) and ABCA1 (P = 6.9 × 10−3) were significantly related to intermediate drusen. LIPC (P = 0.01), ABCA1 (P = 7.8 × 10−4), CFH (P = 1.7 × 10−14), ARMS2/HTRA1 (P = 4.6 × 10−15), C2 (P = 1.6 × 10−4), C3 (P = 7.6 × 10−4), and CFB (P = 0.01) were independently associated with advanced AMD. Similar or slightly weaker association signals were observed for these variants for NV, GA, and large drusen. The E4 allele in APOE was associated with NV (P = 0.04).

Table 3.

Associations between Drusen and Advanced AMD and Effective Alleles for Genetic Factors in Multivariate Models*

| EA† | Intermediate Drusen OR (95% CI) | Large Drusen OR (95% CI) | GA OR (95% CI) | NV OR (95% CI) | Advanced AMD OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10468017 | T | 0.77 (0.61–0.99) | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 0.8 (0.57–1.12) | 0.73 (0.54–1) | 0.7 (0.53–0.93) |

| LIPC | P = 0.04 | P = 0.06 | P = 0.19 | P = 0.05 | P = 0.01 | |

| rs1883025 | T | 0.71 (0.56–0.91) | 0.64 (0.5–0.82) | 0.64 (0.45–0.91) | 0.55 (0.4–0.76) | 0.61 (0.46–0.81) |

| ABCA1 | P = 6.9 × 10−3 | P = 3.9 × 10−4 | P = 0.01 | P = 3.0 × 10−4 | P = 7.8 × 10−4 | |

| rs3764261 | A | 1.1 (0.86–1.4) | 1.12 (0.87–1.44) | 1.08 (0.76–1.52) | 1.29 (0.96–1.74) | 1.21 (0.92–1.59) |

| CETP | P = 0.46 | P = 0.37 | P = 0.68 | P = 0.09 | P = 0.17 | |

| APOE | E4 | 0.89 (0.62–1.28) | 0.85 (0.58–1.24) | 0.67 (0.39–1.16) | 0.61 (0.38–0.97) | 0.68 (0.44–1.04) |

| P = 0.52 | P = 0.39 | P = 0.15 | P = 0.04 | P = 0.07 | ||

| rs1061170 | C | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | 1.37 (1.09–1.73) | 2.32 (1.67–3.21) | 3.38 (2.52–4.54) | 2.77 (2.14–3.59) |

| CFH | P = 0.86 | P = 7.1 × 10−3 | P = 4.9 × 10−7 | P = 6.3 × 10−16 | P = 1.7 × 10−14 | |

| rs10490924 | T | 1.2 (0.9–1.61) | 1.72 (1.29–2.29) | 2.98 (2.05–4.35) | 3.82 (2.76–5.31) | 3.35 (2.48–4.53) |

| ARMS2/HTRA1 | P = 0.22 | P = 2.1 × 10−4 | P = 1.3 × 10−8 | P = 1.0 × 10−15 | P = 4.6 × 10−15 | |

| rs9332739 | C | 0.68 (0.41–1.15) | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | 0.36 (0.15–0.88) | 0.23 (0.11–0.48) | 0.27 (0.14–0.54) |

| C2 | P = 0.15 | P = 0.05 | P = 0.02 | P = 9.2 × 10−5 | P = 1.6 × 10−4 | |

| rs2230199 | G | 1.1 (0.82–1.47) | 1.4 (1.04–1.87) | 1.71 (1.17–2.51) | 1.97 (1.39–2.8) | 1.72 (1.26–2.36) |

| C3 | P = 0.52 | P = 0.03 | P = 5.5 × 10−3 | P = 1.5 × 10−4 | P = 7.6 × 10−4 | |

| rs641153 | T | 0.91 (0.6–1.37) | 0.69 (0.45–1.05) | 0.7 (0.37–1.33) | 0.41 (0.23–0.74) | 0.53 (0.31–0.88) |

| CFB | P = 0.64 | P = 0.08 | P = 0.28 | P = 2.8 × 10−3 | P = 0.01 | |

| rs10033900 | T | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 1.35 (0.99–1.85) | 1.3 (0.98–1.72) | 1.28 (0.99–1.65) |

| CFI | P = 0.37 | P = 0.20 | P = 0.06 | P = 0.07 | P = 0.06 |

Significant results (P < 0.05) are shown in bold.

Tests for linear trend in multivariate models which include all the SNPs in the table and also age, sex, education (≤ high school vs. >high school), smoking (never, past, current), BMI (<25, 25–29.9, 30+), antioxidant treatment.

EA, effective allele of which the genetic effect were shown for each SNP.

Table 4 shows the relationship between AMD phenotypes and genotypes for ABCA1 and LIPC based on multivariate logistic models controlling for all genetic, demographic, and behavioral risk factors. The TT genotype of LIPC (rs10468017) was protective against intermediate drusen (OR [95% CI] = 0.52 [0.30–0.89]; P = 0.018), large drusen (OR [95% CI] = 0.55 [0.31–0.95]; P = 0.033), and advanced AMD (OR [95% CI] = 0.37 [0.19–0.71], P = 2.8 × 10−3). The CT genotype of LIPC (rs10468017) was not significant, suggesting that the genetic effect of this locus best fits a recessive genetic model. Using the collapsed genotypes of CC and CT as the reference genotype, we found that the TT homozygous genotype of LIPC was consistently associated with a reduced risk of intermediate, large drusen, and advanced AMD. Both homozygous and heterozygous genotypes with the T allele of ABCA1 (rs1883025) were protective against intermediate drusen (TT: P = 0.011, OR [95% CI] = 0.48 [0.27–0.85]; CT: P = 0.037, OR [95% CI] = 0.70 [0.50–0.98]), large drusen (TT: P = 3.1 × 10−3, OR [95% CI] = 0.41 [0.23–0.74]; CT: P = 5.8 × 10−3, OR [95% CI] = 0.62 [0.44–0.87]), and advanced AMD (TT: P = 3.5 × 10−3, OR [95% CI] = 0.35 [0.17–0.71]; CT, P = 6.8 × 10−3, OR [95% CI] = 0.59 [0.40–0.87]). The genetic effect of the T allele of ABCA1 (rs1883025) seems to fit an additive genetic model. Although the P values for both the LIPC and the ABCA1 genes were higher in the GA group than in the NV group, possibly because of the smaller sample size in the GA group, the estimates of the effects of these genes on GA and NV were similar.

Table 4.

Associations between Drusen and Advanced AMD and LIPC and ABCA1 Genotypes in Multivariate Models

| Intermediate Drusen (765/203*) |

Large Drusen (901/203*) |

GA (245/203*) |

NV (778/203*) |

Advanced AMD (1023/203*) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | |

| LIPC:rs10468017 | ||||||||||

| CC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| TC | 0.85 (0.60–1.19) | 0.34 | 0.88 (0.63–1.25) | 0.48 | 0.98 (0.60–1.60) | 0.94 | 0.96 (0.63–1.46) | 0.83 | 0.88 (0.60–1.30) | 0.51 |

| TT | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) | 0.018 | 0.55 (0.31–0.95) | 0.033 | 0.48 (0.21–1.10) | 0.083 | 0.39 (0.18–0.81) | 0.012 | 0.37 (0.19–0.71) | 2.8 × 10−3 |

| TT vs CC/TC | 0.56 (0.33–0.94) | 0.029 | 0.58 (0.34–0.98) | 0.043 | 0.48 (0.21–1.08) | 0.076 | 0.39 (0.19–0.81) | 0.01 | 0.39 (0.21–0.74) | 3.4 × 10−3 |

| ABCA1:rs1883025 | ||||||||||

| CC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| CT | 0.70 (0.50–0.98) | 0.037 | 0.62 (0.44–0.87) | 5.8 × 10−3 | 0.56 (0.34–0.90) | 0.017 | 0.58 (0.39–0.88) | 0.011 | 0.59 (0.40–0.87) | 6.8 × 10−3 |

| TT | 0.48 (0.27–0.85) | 0.011 | 0.41 (0.23–0.74) | 3.1 × 10−3 | 0.44 (0.19–1.05) | 0.065 | 0.26 (0.11–0.58) | 1.1 × 10−3 | 0.35 (0.17–0.71) | 3.5 × 10−3 |

Cases/controls, n.

Multivariate polytomous model including the genotypes of LIPC and ABCA1 and adjusted for age, sex, education (≤high school vs. >high school), smoking (never, past, current), BMI (<25, 25–29.9, 30+), antioxidant treatment, CFH Y402H (TT, CT, CC), ARMS2/HTRA1 (GG, GT, TT), C2 (GG, CG/CC), C3 (CC, CG, GG), CFB (CC, CT/TT), CFI (TT, CT, CC), CETP (AA, AC, CC), and APOE (E4, E2/E3). Significant results (P < 0.05) are shown in bold.

We also tested the effects of interactions between the genetic factors in the complement pathway and genes in other pathways, on risk of drusen phenotypes and advanced AMD (Supplementary Table S1, http://www.iovs.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1167/iovs.10-7070/-/DCSupplemental). None of the gene interactions was significantly related to risk of drusen or advanced AMD. The present study may not have sufficient power to evaluate the small effects of interactions between the genetic variants.

Discussion

In this study, we present novel findings that variants in the LIPC and ABCA1 genes in the HDL cholesterol/lipoprotein pathway are likely to be associated with drusen accumulation in the early stages of AMD. This study adds new information beyond the initial discovery, replication and evaluation of these two genes which assessed associations between advanced AMD or a combined phenotype and controls.39,40,50,51 We evaluated the effects of these genes on separate groups of early, intermediate, and advanced forms of AMD in a large cohort, and controlled for demographic and behavioral factors including age, sex, BMI, smoking, education, and antioxidant treatment and other genes related to AMD.

The SNP rs10468017, located in the promoter region of LIPC on chromosome 15, is a functional variant that regulates serum HDL levels by controlling expression level of LIPC.52,53 Serum HDL level was estimated to be 100 μmol/L higher with each copy of the T allele at rs10468017 in a large GWAS study for dyslipidemia.38 The T allele of rs1883025 in ABCA1, which is associated with decreased HDL levels,38 is also inversely associated with the risk of developing intermediate drusen, large drusen, and advanced AMD in this study. Since the allele in ABCA1, which decreases HDL levels, and the allele in LIPC, which increases HDL levels, are both associated with decreasing risk of advanced AMD and drusen, it is not likely that these genes influence the risk of AMD through the same pathway(s) that regulate serum HDL levels. In our recent study, higher serum HDL was associated with lower risk of AMD, and LIPC was associated with reduced risk of advanced AMD, independent of serum levels of HDL,51 suggesting that another mechanism is involved.

LIPC39 and ABCA154 have been shown to be expressed in the retina and RPE.55 LIPC56,57 and ABCA158,59 have also been synthesized and expressed in macrophages, which are the predominant cells involved in creating the progressive plaque lesions of atherosclerosis.60 ABCA1 is believed to suppress atherosclerotic lesions as an anti-inflammatory receptor that exports cholesterol from arterial macrophages.61,62 Drusen may develop by a similar mechanism as atherosclerotic plaque, except that lipoproteins accumulated in Bruch's membrane are likely to be of intraocular origin.63,64 Macrophages have also been found in Bruch's membrane and are related to early and advanced AMD.65,66 Combining this evidence with our findings of an inverse association between LIPC and ABCA1 with drusen, it is possible that functional variants regulating expression levels of LIPC and ABCA1 promote cholesterol efflux, reduce the activation of the inflammatory pathway in subretinal macrophages, and result in less drusen accumulation.

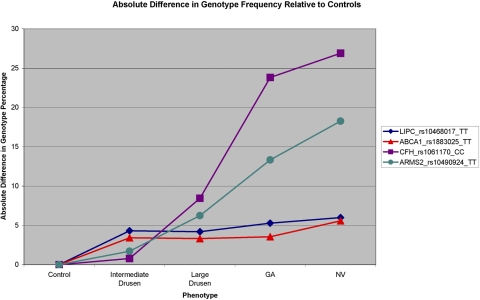

Figure 1 shows the absolute difference in the specific risk/protective genotype frequencies of variants in CFH (Y402H), ARMS2/HTRA1, ABCA1, and LIPC relative to the genotype frequencies in the control group. The largest differences in TT genotype frequencies in the ABCA1 and LIPC genes are between the control stage and the intermediate drusen stage. For intermediate and large drusen GA and NV, there is little change in frequencies of the TT genotype in the ABCA1 and LIPC genes. This pattern of genotype frequencies in ABCA1 and LIPC is distinctive from the pattern in ARMS2/HTRA1 and the complement genes, in which the greatest frequency changes are seen between the stage of large drusen and advanced AMD (Fig. 1). Our results suggest that the variants in the HDL genes are involved in drusen initiation and accumulation and that the complement pathway is activated later as a result of inflammatory responses due to drusen accumulation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that genes in the complement pathway and ARMS2/HTRA1 are also involved in early stages of AMD, especially considering that so many protein products of complement-related genes constitute the makeup of drusen. It has been reported that variants in the CFH gene may cause basal laminar drusen in young adults,67 and CFH has also been related to small, hard macular drusen in a sample with relatively young average age (30–66 years).68 Most of the individuals with advanced AMD in our dataset with the risk alleles in CFH and ARMS2/HTRA1 are older subjects who had drusen before progression to advanced stages. As strong risk factors for the progression to advanced AMD,20,69 CFH and ARMS2/HTRA1 may also have contributed to early-stage drusen accumulation when the patients were younger.

Figure 1.

Absolute difference in genotype frequency relative to controls of the TT genotype of rs10468017 in LIPC, the TT genotype of rs1883025 in ABCA1, the CC genotype of rs1061170 in CFH, and the TT genotype of rs10490924 in ARMS2/HTRA1 of intermediate drusen, large drusen, GA, and NV disease.

In our previous GWAS,39,40 there was some evidence that the A allele of rs3764261 in CETP increased the risk of advanced AMD (OR [95% CI] = 1.12 [1.04–1.20]), although this was not genome-wide significant (P = 1.41 × 10−3). In the present study, the AA genotype at this locus is overrepresented in NV cases compared with the controls, indicating the same direction of genetic effect on this locus, controlling for demographic, behavioral, and other known genetic factors that were not included in our original GWAS. The E4 allele of APOE tended to reduce risk of NV; however, the magnitude of the effect in our sample was much smaller than previously reported. Subjects with the E4 allele (mean age, 78.54 ± 4.97 years) were significantly younger (P = 0.0014) than subjects without the E4 allele (mean age, 79.24 ± 4.95, years) in this sample. Thus, it is possible that the protective effect of the E4 allele on NV is confounded by the selection pressure of APOE in older subjects.

Strengths of the study include the large, well characterized population of subjects in carefully defined AMD stages, recruited from various geographic regions around the United States; the standardized collection of risk factor information; direct measurements of height and weight; and classification of maculopathy by well-documented ophthalmic examinations and fundus photography. The phenotype grades were unlikely to be misclassified because they were assigned without knowledge of risk factors or genotype and were assigned based on phenotypic information from multiple diagnostic records. We evaluated early, intermediate, and advanced AMD stages and expanded the evaluation of the complicated genetic effects on AMD. Results suggest that a functional variant plays an important role during an early stage of AMD. Therefore, it would be helpful to collect samples across all spectra of the disease and analyses could be done separately for different stages. Prospective studies and larger independent samples are needed to confirm and expand upon these findings.

In conclusion, T alleles in two genes in the HDL pathway, LIPC and ABCA1, are protective for intermediate and large drusen phenotypes, as well as advanced AMD, independent of other genetic and environmental factors. These genes in the HDL pathway may play important roles in drusen accumulation in early and intermediate stages of AMD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gordon Huggins, PhD (Tufts Medical Center), for assistance with the genotyping.

Footnotes

Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, May 2010.

Supported by an anonymous donor (JMS); in part by grant R01-EY11309 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; the Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund, Inc.; an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY; the American Macular Degeneration Foundation, Northampton, MA; the Elizabeth O'Brien Trust; the Virginia B. Smith Trust; and the Macular Degeneration Research Fund of the Ophthalmic Epidemiology and Genetics Service, New England Eye Center, Tufts Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Disclosure: Y. Yu, None; R. Reynolds, None; J. Fagerness, None; B. Rosner, None; M.J. Daly, P; J.M. Seddon, P

References

- 1. Seddon JM, Sobrin L. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. In: Albert D, Miller J, Azar D, Blodi B. eds. Albert & Jakobiec's Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007:413–422 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Jong PT. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1474–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zarbin MA. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:598–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch's membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:705–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fariss RN, Apte SS, Olsen BR, Iwata K, Milam AH. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 is a component of Bruch's membrane of the eye. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:323–328 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hageman GS, Mullins RF, Russell SR, Johnson LV, Anderson DH. Vitronectin is a constituent of ocular drusen and the vitronectin gene is expressed in human retinal pigmented epithelial cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luibl V, Isas JM, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Langen R, Chen J. Drusen deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain nonfibrillar amyloid oligomers. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:378–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Staples MK, Anderson DH. Complement activation and inflammatory processes in drusen formation and age related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:887–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li CM, Clark ME, Rudolf M, Curcio CA. Distribution and composition of esterified and unesterified cholesterol in extra-macular drusen. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang L, Clark ME, Crossman DK, et al. Abundant lipid and protein components of drusen. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, Rudolf M. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in retinal aging and age-related macular degeneration. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:451–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seddon JM, Cote J, Page WF, Aggen SH, Neale MC. The US twin study of age-related macular degeneration: relative roles of genetic and environmental influences. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seddon JM, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in women. JAMA. 1996;276:1141–1146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seddon JM, Cote J, Davis N, Rosner B. Progression of age-related macular degeneration: association with body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-hip ratio. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:785–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van Leeuwen R, et al. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1280–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Seddon JM, Ferris FL., 3rd Risk factors for the incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS). AREDS report no. 19. Ophthalmology 2005;112:533–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seddon JM, George S, Rosner B, Klein ML. CFH gene variant, Y402H, and smoking, body mass index, environmental associations with advanced age-related macular degeneration. Hum Hered. 2006;61:157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seddon JM, George S, Rosner B. Cigarette smoking, fish consumption, omega-3 fatty acid intake, and associations with age-related macular degeneration: the US Twin Study of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:995–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seddon JM, Francis PJ, George S, Schultz DW, Rosner B, Klein ML. Association of CFH Y402H and LOC387715 A69S with progression of age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2007;297:1793–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, et al. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:419–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, et al. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, et al. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7227–7232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maller J, George S, Purcell S, et al. Common variation in three genes, including a noncoding variant in CFH, strongly influences risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1055–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li M, Atmaca-Sonmez P, Othman M, et al. CFH haplotypes without the Y402H coding variant show strong association with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1049–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards AO, Ritter R, 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, et al. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2006;38:458–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maller JB, Fagerness JA, Reynolds RC, Neale BM, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Variation in complement factor 3 is associated with risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1200–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yates JR, Sepp T, Matharu BK, et al. Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:553–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fagerness JA, Maller JB, Neale BM, Reynolds RC, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Variation near complement factor I is associated with risk of advanced AMD. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:100–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivera A, Fisher SA, Fritsche LG, et al. Hypothetical LOC387715 is a second major susceptibility gene for age-related macular degeneration, contributing independently of complement factor H to disease risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3227–3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang Z, Camp NJ, Sun H, et al. A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006;314:992–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seddon JM, Reynolds R, Rosner B. Peripheral retinal drusen and reticular pigment: association with CFHY402H and CFHrs1410996 genotypes in family and twin studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:586–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andreoli MT, Morrison MA, Kim BJ, et al. Comprehensive analysis of complement factor H and LOC387715/ARMS2/HTRA1 variants with respect to phenotype in advanced age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:869–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Magnusson KP, Duan S, Sigurdsson H, et al. CFH Y402H confers similar risk of soft drusen and both forms of advanced AMD. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grassi MA, Folk JC, Scheetz TE, Taylor CM, Sheffield VC, Stone EM. Complement factor H polymorphism p.Tyr402His and cuticular drusen. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasham SN, Pillarisetti S. Vascular lipases, inflammation and atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;372:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, et al. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7395–7400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, et al. Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7401–7406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Souied EH, Benlian P, Amouyel P, et al. The epsilon4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene as a potential protective factor for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baird PN, Richardson AJ, Robman LD, et al. Apolipoprotein (APOE) gene is associated with progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Hum Mutat. 2006;27:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Losonczy G, Fekete A, Voko Z, et al. Analysis of complement factor H Y402H, LOC387715, HTRA1 polymorphisms and ApoE alleles with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration in Hungarian patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fritsche LG, Freitag-Wolf S, Bettecken T, et al. Age-related macular degeneration and functional promoter and coding variants of the apolipoprotein E gene. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1048–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seddon JM, Sharma S, Adelman RA. Evaluation of the clinical age-related maculopathy staging system. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): design implications AREDS report no. 1. Control Clin Trials 1999;20:573–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dewan A, Liu M, Hartman S, et al. HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2006;314:989–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jakobsdottir J, Conley YP, Weeks DE, Mah TS, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB. Susceptibility genes for age-related maculopathy on chromosome 10q26. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:389–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Seddon JM, Reynolds R, Rosner B. Associations of smoking, body mass index, dietary lutein, and the LIPC gene variant rs10468017 with advanced age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2412–2424 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reynolds R, Rosner B, Seddon JM. Serum lipid biomarkers and hepatic lipase gene associations with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1989–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rufibach LE, Duncan SA, Battle M, Deeb SS. Transcriptional regulation of the human hepatic lipase (LIPC) gene promoter. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1463–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grarup N, Andreasen CH, Andersen MK, et al. The -250G>A promoter variant in hepatic lipase associates with elevated fasting serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol modulated by interaction with physical activity in a study of 16,156 Danish subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2294–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tserentsoodol N, Gordiyenko NV, Pascual I, Lee JW, Fliesler SJ, Rodriguez IR. Intraretinal lipid transport is dependent on high density lipoprotein-like particles and class B scavenger receptors. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1319–1333 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Duncan KG, Hosseini K, Bailey KR, et al. Expression of reverse cholesterol transport proteins ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) and scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1116–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nong Z, Gonzalez-Navarro H, Amar M, et al. Hepatic lipase expression in macrophages contributes to atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient and LCAT-transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:367–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gonzalez-Navarro H, Nong Z, Freeman L, Bensadoun A, Peterson K, Santamarina-Fojo S. Identification of mouse and human macrophages as a site of synthesis of hepatic lipase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:671–675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schmitz G, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) in macrophages: a dual function in inflammation and lipid metabolism? Pathobiology. 1999;67:236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Oram JF, Lawn RM, Garvin MR, Wade DP. ABCA1 is the cAMP-inducible apolipoprotein receptor that mediates cholesterol secretion from macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34508–34511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lucas AD, Greaves DR. Atherosclerosis: role of chemokines and macrophages. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2001;3:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tang C, Liu Y, Kessler PS, Vaughan AM, Oram JF. The macrophage cholesterol exporter ABCA1 functions as an anti-inflammatory receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32336–32343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:139–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Curcio CA, Rudolf M, Wang L. Histochemistry and lipid profiling combine for insights into aging and age-related maculopathy. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;580:267–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Curcio CA, Johnson M, Huang JD, Rudolf M. Aging, age-related macular degeneration, and the response-to-retention of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:393–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cherepanoff S, McMenamin PG, Gillies MC, Kettle E, Sarks SH. Bruch's membrane and choroidal macrophages in early and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:918–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP, Sarks SH. Macrophages related to Bruch's membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond). 1990;4(Pt 4):613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Hoyng CB, et al. Basal laminar drusen caused by compound heterozygous variants in the CFH gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:516–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Munch IC, Ek J, Kessel L, et al. Small, hard macular drusen and peripheral drusen: associations with AMD genotypes in the Inter99 Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2317–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Seddon JM, Reynolds R, Maller J, Fagerness JA, Daly MJ, Rosner B. Prediction model for prevalence and incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration based on genetic, demographic, and environmental variables. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2044–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.