This article describes for the first time the expression and regulation of Bcl-xL in mouse RPE and the critical role of this protein in mouse RPE cell survival.

Abstract

Purpose.

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell survival plays a critical role in normal physiology and in retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). We have previously demonstrated that Bcl-xL is an important cell survival protein in human RPE (hRPE) cells. Herein, we determined the role of Bcl-xL as a survival protein in mouse RPE (mRPE) cells.

Methods.

Survival factor gene expression and Bcl-xL protein distribution were determined using qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry, respectively. Cultured mRPE cells were transfected with two modified 2′-O-methoxyethoxy antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs): Bcl-xL–mismatched control and Bcl-xL–specific. Bcl-xL protein levels were analyzed using Western blot. To determine the effects of survival factor regulation in mRPE cells, cultured cells were treated for 24 hours with mouse TNF-α, human IL-1β, and human TNF-α.

Results.

Bcl-xL was the most highly expressed survival factor in both mouse eyecup and cultured mRPE cells, whereas Bax was the most highly expressed antisurvival factor. Bcl-xL was expressed in the RPE layer, and the distribution among the retinal layers was similar to that observed in human eyecups. IL-1β and TNF-α had minimal effect on Bcl-xL and Bax expression and strongly upregulated Traf-1. Transfection with Bcl-xL–specific ASO resulted in markedly diminished Bcl-xL gene expression, Bcl-xL protein levels, and cell number.

Conclusions.

Bcl-xL is the most highly expressed survival gene in mRPE cells and is essential for mRPE cell survival. Our data suggest that mouse tissue is an appropriate model for investigations of RPE survival factor genes.

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell survival plays a critical role in normal ocular physiology and as a determinant of retinal disease. Normally, there is little RPE cell turnover, and the majority of cells last for an individual's lifetime.1 In some diseases, such as geographic atrophy (GA), the advanced form of non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (i.e., RPE cell dysfunction and death) is associated with overlying retinal damage, choriocapillaris atrophy, and progressive vision loss.2,3 Conversely, in other conditions such as proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), RPE cells survive pathologically when they detach from their normal Bruch's membrane substrate and proliferate into the vitreous cavity and onto the retinal surface and undersurface.4,5 Subsequently, RPE-cell–mediated scar contraction can cause worsening of a retinal detachment or redetachment of retinal detachment that was initially successfully repaired.6 The factors responsible for normal RPE cell survival, pathologic survival in diseases such as PVR, and RPE cell death in conditions such as AMD-associated GA are incompletely understood.

RPE cells are subject to numerous threats during their lifetime and have a repertoire of different mechanisms to protect themselves from an untimely demise.7–11 For example, they are continually exposed to endogenous oxidants through daily photoreceptor turnover, light-induced photooxidative stress, and external exposure to oxidants in the environment, such as cigarette smoke and pollutants.12,13 In addition to protective mechanisms such as antioxidants and enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, we have shown that RPE cells possess a variety of survival proteins that serve to promote their existence.7,10 Furthermore, we have found that expression of human RPE (hRPE) cell survival proteins, such as c-IAP1 and Traf-1, are upregulated by IL-1β and TNF-α, cytokines that are thought to be important in AMD and PVR pathogenesis.14,15 The effect of cytokines and oxidants is frequently species-specific.16 The species specificity of cytokine effects on RPE cell survival proteins has not been well described.

Bcl-2 family members are important regulators of cell survival.17 Apoptosis, a programed form of cell death, can maintain physiologic tissue homeostasis. However, apoptosis may also contribute to the pathogenesis of disease.2 Bcl-xL, an integral member of the Bcl-2 protein family, localizes to the outer membrane of the mitochondria, and serves as an apoptosis intrinsic pathway regulator.17–19 For example, Bcl-xL is a critical antiapoptotic factor in murine hepatocytes, and its absence leads to profound hepatic apoptotic cell death.20 In contrast, other Bcl-2 family members such as Bax promote apoptosis, and, when Bax is inhibited, cell survival is enhanced.21 It is believed that the balance of the anti- and proapoptotic proteins determines whether a cell lives or dies.22,23

Bcl-2 family members are generally considered anti- or proapoptotic factors based on their effect on apoptotic cell death. However, these family members are also important regulators of nonapoptotic cell demise. For example, Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and Bax can protect or promote autophagic cell death, respectively.24,25 For this reason, in the present study, we have chosen to use the terms “prosurvival” and “antisurvival factor,” rather than “anti-” or “proapoptotic factor,” respectively, to reflect their varied effects on cell death mechanisms.

We have previously demonstrated a crucial role for Bcl-xL as an hRPE cell survival protein. When hRPE cell Bcl-xL expression was blocked with a Bcl-xL–specific antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), RPE cell survival was significantly decreased.9

Mouse cells and tissues are frequently used as models for human retinal diseases.26 Our finding that Bcl-xL is a key hRPE cell survival protein led us to inquire whether it played a similarly important role in mouse RPE (mRPE) cells. We reasoned that if mRPE cell Bcl-xL expression and regulation were similar to those observed in hRPE cells, these data would support the use of mouse tissues as a model to further explore the role of Bcl-xL in healthy hRPE cells, and in diseases such as AMD and PVR. Herein, we determined the expression, regulation, and functional effect on cell survival of Bcl-xL in mRPE cells.

Materials and Methods

RNA Extraction from Mouse Eyecup

All animal studies conformed to the guidelines of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University. Pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed and maintained in the Duke University Vivarium.

Animals were anesthetized with a 90 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine solution diluted in PBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the eyes were immediately enucleated and cut posterior to the ora serrata to remove the anterior segments. The eyecups (posterior segments) were homogenized on ice. Eyecup total RNA was isolated and purified from cells (RNeasy Plus Mini Kit; Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's specifications.

Human RPE Cell Culture

Human donor eyes were acquired from the North Carolina Donor and Eye Bank and used in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human tissue. RPE cells were cultured from donor eyes as previously described.27 Cells were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Invitrogen), and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2.

Mouse RPE Cell Culture

mRPE cells were harvested and cultured as previously described, with slight modification.8,28,29 Briefly, intact eyes were washed twice with PBS and placed in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 2% dispase (wt/vol) and 0.4 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes. The eyes were cut posterior to the ora serrata to remove the anterior segments. Eyecups were washed with PBS and a chelating agent (VERSENE; Invitrogen). A 2% solution of dispase in serum-free DMEM-high glucose (20 μL) was added to the eyecup, and the samples were incubated for 10 minutes in a humidified chamber at room temperature. The enzymatic solution was removed and the retina was gently separated from the RPE–choroid in DMEM. A 2% solution of dispase (20 μL) was added to the eyecup and incubated for 10 minutes in a humidified chamber at 37°C. This enzymatic solution was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS, and the RPE cells were gently removed from the choroid. Cells were grown for 1 week in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2. After 1 week, the media was changed to DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin.

Cytokine Stimulation of mRPE Cells

Pooled mRPE cells at fourth-passage (2 × 105) were seeded in six-well plates (Corning-Costar Inc., Corning, NY); 24 hours later, the cells were incubated with fresh medium for an additional 24 hours and then starved in serum-free medium for 24 hours. The cells were treated with recombinant mouse TNF-α (mTNF-α; 22 ng/mL; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN), recombinant human TNF-α (hTNF-α; 22 ng/mL; R&D Systems), recombinant human IL-1β (hIL-1β; 5 U/mL; Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA), or with media alone for 24 hours. All cytokine stimulation incubations were performed in serum-free medium.

Mouse and Human Eyecup Tissue Procurement for Immunohistochemistry

Mouse eyes were fixed as previously described.8 Briefly, after eyes were enucleated, a corneal incision was made, and eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 3 hours. The posterior segments were isolated by removing the cornea and lens and then fixed in 1% PFA overnight. Cryosections (6 μm) were fixed in cold acetone for 5 minutes, rehydrated in PBS, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum in 1% BSA (Invitrogen)/PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Bcl-xL was probed using 1:50 dilution primary Bcl-xL antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) in 1% BSA/PBS overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen), a secondary antibody diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA/PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenindole (DAPI; 0.1 μg/μL) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Images were captured using a confocal microscope (Nikon C90i; Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) equipped for epifluorescence.

Human eyes were obtained from the North Carolina Eye Bank (Winston Salem, NC), and 5 hours after enucleation, a small incision was made at the ora serrata. Eyes were fixed in 4% PFA for a minimum of 24 hours, after which the anterior segment was removed. The fixing solution was changed to 1% PFA and eyes were stored at 4°C overnight. For cryopreservation, tissue was then immersed in successive solutions of 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose in PBS for 30 minutes. Samples were sectioned at 10 μm, collected on gelatin-subbed slides, and dried at 50–55°C. Bcl-xL was probed using 1:50 dilution primary Bcl-xL antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) in 1% BSA/PBS overnight at 4°C. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (Invitrogen) diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA/PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (0.1 μg/μL) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Images were captured using a confocal microscope (Nikon C90i) equipped for epifluorescence.

Antisense Oligonucleotide Transfection

RPE cells were seeded in six-well plates (1.0 × 105 cells/well) or 24-well plates (2.0 × 104 cells/well; Corning-Costar) on day 0, and were allowed to grow for 2 days in growth medium (either mouse or human growth medium for mouse or human cells, respectively). Cells were transiently transfected on day 2 postplating as follows. Cells were washed twice with cell wash (Opti-MEM; Invitrogen) and transfected with two different modified 2′-O-methoxyethoxy (MOE) antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), 300 nM: Bcl-xL–specific (TCCCGGTTGCTCTGA[b]GACAT, ISIS 15999; ISIS Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Carlsbad, CA; bold-MOE residues; all internucleotide bonds are phosphorothioate) and Bcl-xL–mismatched control (CCTCGATTCCTGTTA[b]GAGAG, ISIS 355092) with lipofectin (0.006 mg/mL; Invitrogen) and cell wash (Opti-MEM), supplemented with 0.5% BSA for mRPE cells. The Bcl-xL–specific ASO has a complementary mRNA sequence to Bcl-xL. The RNA–DNA heteroduplex forms on binding of the target sequence and is recognized by ribonuclease H as an enzymatic substrate, initiating the degradation of the RNA constituent. At 24 hours posttransfection, transfection medium was removed from the cells, and growth medium was added to the cells. The cells recovered for at least 24 hours before they were harvested for analysis.

Analysis by Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells with a kit (RNeasy Plus Mini Kit), according to the manufacturer's specifications, and synthesized into cDNA using reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR; iScript cDNA Synthesis; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Real-time quantitative analysis (qRT-PCR) was performed as previously described.7 Each qRT-PCR measurement was performed with duplicate samples collected from two separate wells (iCycler IQ; Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). To quantify real-time gene expression, samples were normalized to the threshold cycle (CT) of either human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or mouse peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase A (PPIA) in the corresponding species, where CT represents the PCR cycle number at which the amount of amplified sample product reaches the threshold of 100 RFUs (relative fluorescence units). Expression of each gene evaluated was calculated relative to the expression of the control-transfected group: 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT = [(CT, target − CT, GAPDH, or PPIA)Bcl-xL–specific ASO − (CT-target − CT, GAPDH, or PPIA)Bcl-xL–mismatched control ASO].30 A melting curve for all products was obtained immediately after amplification to confirm the PCR product identity, as previously described.9 PPIA and mouse Bcl-xL primers were used for qRT-PCR quantification to determine the relative amount of gene expression for our experiments. Mouse survival factor primers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mouse Primers for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PPIA | F | GTC CAG GAA TGG CAA GAC CAG C |

| R | GCG AGC AGA TGG GGT AGG GAC | |

| Bcl-2 | F | GTC CCG CCT CTT CAC CTT TCA G |

| R | GAT TCT GGT GTT TCC CCG TTG G | |

| Bcl-x | F | ATG ACT GTG GCT GGT GTG GTT CTG |

| R | GCT GAA GAG AGA GTT GTG GTG GGG | |

| Bcl-xL | F | AAC ATC CCA GCT TCA CAT AAC CCC |

| R | GCG ACC CCA GTT TAC TCC ATC C | |

| c-IAP1 | F | AGA ACA CGC CAA ATG GTT TCC AAG |

| R | TGG GGT GTC TGA AGT GGA CAA CAG | |

| c-IAP2 | F | AGG GAC CAT CAA GGG CAC AGT G |

| R | TTT GGC GGT GTC TCG TGC TAT C | |

| c-FLIP | F | TCC AGA ATG GGC GAA GTA AAG AGC |

| R | AGT CTC TTC ACG GAT GTG CGG AG | |

| Survivin | F | TCA TCC ACT GCC CTA CCG AGA AC |

| R | TCT ATC GGG TTG TCA TCG GGT TC | |

| TRAF-1 | F | GCA GTC ACC CAA GCA CGC CTA C |

| R | AGC TGG TTC TGT CAG GAG ACA CCC | |

| TRAF-2 | F | CTA CTT GAA TGG CGA CGG CAC TG |

| R | ACT GCA ACA GAG CAT CAT TGG GG | |

| Bad | F | GGG AGC AAC ATT CAT CAG CAG G |

| R | CAT CCC TTC ATC CTC CTC GGT C | |

| Bak-1 | F | AAG GTG GGC TGC GAT GAG TCC |

| R | GGG TCT CCT GTT CCT GCT GGT G | |

| Bax | F | GCG TGG TTG CCC TCT TCT ACT TTG |

| R | AGT CCA GTG TCC AGC CCA TGA TG | |

| Bim | F | CAC TGG TTG CTG GCT TTG CTG |

| R | TCC TTG CTC CTG AAA TGA CCT GG |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Protein Extracts and Western Blot

Protein was extracted from adherent cultured mRPE cells in duplicate wells 4 days after plating. Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS), supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) was used to measure cell extract protein concentration. Electrophoretic blotting equipment (Mini Trans-Blot; Bio-Rad) was used to electrophorese and transfer an equal amount of protein (30 μg) to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), as previously described.31 Briefly, the membranes were probed with rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against Bcl-xL for an overnight incubation (1:1000 in 2.5% milk; Cell Signaling Technology), followed by a 1-hour incubation with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000 in 2.5% milk; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) at room temperature. An enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) fluorescence detection kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was used to visualize immunoreactive bands on the membrane.

Cell Counts

Both hRPE and mRPE cells were seeded in quadruplicate wells of 24-well plates at densities of 2 × 104 cells/well. Counts were determined at 3 days posttransfection. After media was removed from each group, the cells were washed with PBS and trypsinized. Cell number was determined with a trypan blue exclusion assay. Live cells that excluded 0.2% trypan blue dye were counted with a hemacytometer (Brightline Hemacytometer; Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA).

Statistical Analysis

qRT-PCR was performed in duplicates and the data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Analysis of relative gene expression using qRT-PCR was performed using Student's t-test (Fig. 1, Table 2; also see Fig. 5) and F test (Fig. 2). For the cell count assays, a Student's t-test was performed to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in the mean values for cell count in experimental groups compared with the control groups.

Figure 1.

Expression of survival factor genes in mouse eyecups. qRT-PCR was used to determine gene expression. Expression was normalized to PPIA, a housekeeping gene for the mouse, and is relative to Bcl-2 expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Table 2.

Effect of Cytokines on Pro- and Antisurvival Gene Expression in mRPE Cells

| Gene | mTNF-α | hIL-1β | hTNF-α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosurvival | |||

| Survivin | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.3* |

| Bcl-xL | 2.3 ± 0.9* | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6* |

| c-FLIP | 2.3 ± 0.5** | 2.0 ± 0.3** | 3.3 ± 2.0 |

| TRAF-2 | 3.5 ± 0.8** | 3.8 ± 1.0** | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| c-IAP1 | 6.2 ± 0.9** | 3.9 ± 0.6* | 7.3 ± 4.1 |

| c-IAP2 | 12.2 ± 2.5** | 6.8 ± 1.9* | 17.8 ± 3.3** |

| TRAF-1 | 57.0 ± 42.9* | 15.1 ± 17.1 | 120.2 ± 47.5* |

| Antisurvival | |||

| Bad | 1.9 ± 0.4* | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.6 |

| Bax | 1.5 ± 0.2** | 1.5 ± 0.2** | 1.2 ± 0.6** |

| Bik | 1.6 ± 0.6** | 1.2 ± 0.2** | 2.7 ± 1.8 |

| Bak-1 | 3.7 ± 1.0* | 2.7 ± 1.2* | 4.7 ± 2.0* |

| Bid | 9.1 ± 1.2** | 3.1 ± 0.9** | 13.4 ± 4.0** |

Pooled mRPE cells were treated with either medium alone (basal), m- or hTNF-α (22 ng/mL), or hIL-1β (5 U/mL) in serum-free DMEM for 24 hours. RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed to synthesize cDNA. The transcripts were amplified using gene-specific primer pairs and quantified using qRT-PCR. Numbers correspond to the fold-difference between cytokine-treated gene expression and basal gene expression, after normalization to the reference gene, PPIA.

Data are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells;

P < 0.005 vs. untreated cells.

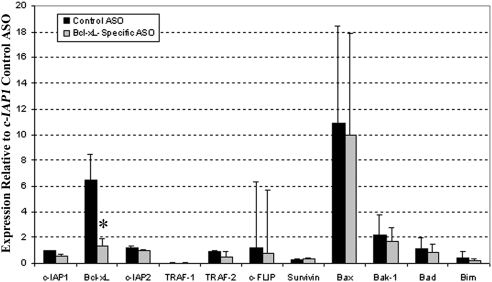

Figure 5.

Survival factor gene expression after Bcl-xL inhibition. Pooled mRPE cells were transfected with 300 nM control ASO and Bcl-xL–specific ASO. RNA was collected 4 days postplating and cDNA was synthesized. qRT-PCR was used to determine gene expression of pro- and antisurvival factors. Gene expression of survival factor genes was normalized to PPIA, a housekeeping gene for the mouse, and is relative to the expression of the control ASO-transfected Bcl-xL gene. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.007 vs. Bcl-xL control ASO.

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of survival genes in primary culture and fourth-passaged mRPE cells. Pooled mRPE cells were cultured as described above. qRT-PCR was used to determine gene expression. Expression was normalized to PPIA, a mouse housekeeping gene, and is relative to Bcl-2 expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. Bcl-xL in primary culture cells.

Results

mRNA Expression of Survival Factor Genes in Mouse Eyecups and Cultured mRPE Cells

Among prosurvival genes in freshly isolated mouse eyecups, Bcl-xL was most highly expressed. Bcl-x, c-IAP1, c-FLIP, Bcl-2, and Traf-2 were expressed at intermediate levels and Traf-1 and c-IAP2 were expressed at low levels. Among antisurvival genes, Bax was most highly expressed and other genes were expressed at lower levels (Fig. 1).

We next determined whether survival factor gene expression in cultured mRPE cells was similar to that observed in freshly isolated mouse eyecups. As in freshly isolated mouse eyecups, Bcl-xL was the most highly expressed mRNA in cultured mRPE cells, followed by Bcl-x, c-IAP1, and c-FLIP at intermediate levels; the remainder of the prosurvival genes were expressed at low levels (Fig. 2). Interestingly, c-IAP1 in cultured cells was expressed at a low level compared with that of other survival factor genes, whereas there was intermediate expression of c-IAP1 in freshly isolated mouse eyecups. Antisurvival gene expression in cultured cells also showed a distribution similar to that observed in freshly isolated mouse eyecups. Bax was the most highly expressed, Bak-1 was expressed at intermediate levels, and Bad and Bim were expressed at low levels. Bax was expressed statistically significantly higher than Bcl-xL in primary mRPE cells. Bax was also expressed more highly than Bcl-xL in fourth-passage mRPE cells, although not statistically significant (Fig. 2).

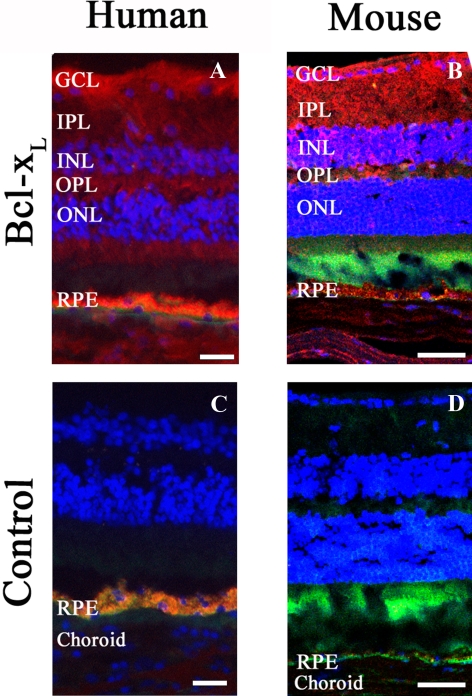

Immunofluorescent Localization of Bcl-xL in Human and Mouse Posterior Segments

Since Bcl-xL is the most highly expressed prosurvival gene both in freshly isolated eyecups and in culture, we characterized Bcl-xL protein distribution in human and mouse eyecups by immunohistochemistry. Both human and mouse eyecups showed Bcl-xL staining in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), inner nuclear layer (INL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), and RPE. Human eyecups showed particularly strong staining in the GCL and RPE (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Bcl-xL immunofluorescent localization within representative posterior segments of human and mouse eyecups. Bcl-xL was probed with 1:50 dilution primary Bcl-xL antibody (red) in human (A) and mouse eyecups (B). Nuclei stained with DAPI (0.1 μg/μL) are blue and autofluorescence appears green. Negative controls (C, D) were treated with 1% BSA/PBS alone without primary antibody. Similar results were obtained from two individual human samples and two different mice. Scale bar: (A, C) 20 μm; (B, D) 50 μm.

Effect of Cytokines on Survival Factor Genes in mRPE Cells

Both human and mouse TNF-α and, to a lesser extent, hIL-1β upregulated most genes studied. Of the prosurvival genes, Traf-1 was most upregulated by cytokine treatment, especially with hTNF-α. Bcl-xL expression was only modestly enhanced by mTNF-α and hTNF-α. Of the antisurvival genes, Bid was most upregulated, especially with hTNF-α (Table 2).

Effects of Bcl-xL Inhibition on mRNA Expression of Survival Factors and Protein Levels

To determine the functional consequences of Bcl-xL inhibition, we first determined the effect of Bcl-xL–specific ASO on prosurvival gene expression and on Bcl-xL protein levels. As expected, 4 days postplating, after Bcl-xL–specific ASO transfection, Bcl-xL mRNA expression was significantly decreased compared with levels in cells transfected with control ASO (Fig. 5). Bcl-xL protein levels were also appreciably decreased in Bcl-xL–specific ASO-transfected cells compared with the control ASO-transfected cells (Fig. 4). To determine the specificity of this effect, we quantified the effect of Bcl-xL knock down on the expression of several pro- and antisurvival genes. Bcl-xL–specific ASO transfection did not significantly alter other pro- or antisurvival gene expression when compared with control ASO (Fig. 5). However, Bax expression was the most highly expressed antisurvival factor gene for both Bcl-xL–specific ASO and control ASO-treated cells.

Figure 4.

Bcl-xL protein levels in mRPE cells treated with ASOs. Pooled mRPE cells were transfected with 300 nM control ASO or Bcl-xL–specific ASO. Cytoplasmic protein (30 μg) was collected from mRPE cells in duplicate wells at 4 days postplating. Top: Western blot probed with Bcl-xL antibody (diluted 1:1000). Middle: membrane from top was stripped and reprobed with GAPDH antibody, a housekeeping protein used as a control (diluted 1:10,000). Bottom: densitometry was performed to determine the relative quantity of Bcl-xL proteins in each lane of the Western blot. Each lane was normalized to the GAPDH Western blot. The lanes of each Western blot correspond to the labels of the densitometry graph.

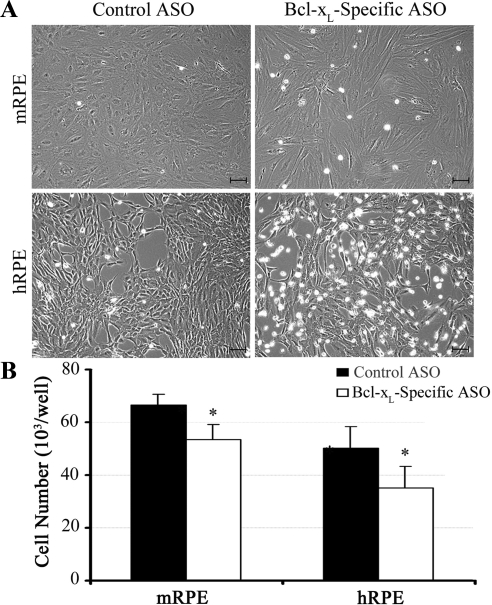

Effect of Bcl-xL Inhibition on Cell Death in Mouse and Human RPE

Once we confirmed that the Bcl-xL–specific ASO inhibited Bcl-xL gene expression and reduced Bcl-xL protein levels, we examined the effects of reduced Bcl-xL on cell viability. At 3 days posttransfection, cells treated with Bcl-xL–specific ASO were more rounded and detached than those treated with control ASO or medium alone. This effect was more evident in hRPE cells compared with mRPE cells. However, in both species there was a marked increase in cell death in experimental groups compared with controls. At 3 days posttransfection, the cell number was significantly reduced in Bcl-xL–specific ASO-treated groups compared with controls (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of Bcl-xL inhibition on human and mouse RPE cell morphology and cell number. Cell morphology (A) and cell numbers (B) in cells treated with Bcl-xL–specific ASO or control ASO 3 days posttransfection. Data represent the mean of quadruplicate wells. *P < 0.03 for the difference in both human and mouse cell numbers of Bcl-xL–specific and control ASO-transfected cells. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that in mRPE, Bcl-xL is the most highly expressed survival gene, among those examined, and levels are modestly upregulated by cytokines. Functional Bcl-xL inhibition alters cell morphology and reduces cell survival. These results closely resemble our findings in hRPE cells and support a critical survival role of Bcl-xL in both mouse and human cells.9

We chose to focus on characterizing the expression and functional role of Bcl-xL in mRPE cells. Prominent Bcl-xL expression was observed in mRPE cells and promoted mRPE survival. Furthermore, Bcl-xL is upregulated in light-exposed mouse photoreceptors and is thought to protect the photoreceptors from light-induced damage.32

In the human eyecup, as in the mouse, there was notable Bcl-xL staining in the RPE and GCL, which corresponds to its importance as a key retinal ganglion cell survival protein.33 Also, as in mouse eyecups, Bcl-xL was widely distributed in other human retinal layers, including the IPL, INL, OPL, and ONL, suggesting that Bcl-xL plays an important role in mouse and human RPE and neural retinal survival.

Bcl-xL–specific ASO dramatically inhibited Bcl-xL mRPE cell gene expression and protein levels. There was a significant decrease in cell viability and deterioration in cell morphology, which was similar to what we observed when hRPE cells were treated with Bcl-xL–specific ASO.9 These data indicate that Bcl-xL is an important survival factor gene in both mouse and human RPE cells and that mRPE cells respond in a manner similar to that of hRPE cells.

It is believed that the relative balance of pro- and antisurvival factor genes determines whether cells live or die.34 Therefore, we examined the effect of Bcl-xL–specific ASO treatment on other survival factor genes expressed by RPE cells. Bcl-xL–specific ASO treatment was specific only to Bcl-xL because other pro- and antisurvival gene expressions were not significantly influenced. Although Bax, a key regulator of cell death, was the most highly expressed antisurvival factor on both Bcl-xL–specific and control ASO treatment, Bcl-xL was the only survival factor inhibited by Bcl-xL–specific treatment.

It has been previously shown that Bcl-xL selectively interacts with and prevents Bax activation.35 Additionally, Antony and colleagues36 showed that neuroprotectin promoted heterodimerization of Bax with Bcl-xL in RPE cells, thus enhancing the prosurvival effect of Bcl-xL. We hypothesized that inhibition of Bcl-xL expression by Bcl-xL–specific ASO would reduce the availability of Bcl-xL to interact with Bax, thus resulting in Bax homodimer formation and increased Bax expression and cell death. Although Bax expression levels were unaltered by Bcl-xL–specific ASO, there may be other underlying mechanisms that contribute to the enhanced cell death observed. Detailed experiments to examine a potential link between Bcl-xL inhibition on Bax-mediated RPE cell death is beyond the scope of the present study, although experiments to explore this relationship are under way in our laboratory.

IL-1β and TNF-α are widely expressed throughout the vitreous, subretinal fluid, and epiretinal membranes.37 We have previously shown that these cytokines are critical activators of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway in RPE cells, and that certain survival proteins including c-FLIP and TRAF1 are upregulated in RPE cells in an NF-κB–dependent manner. In contrast, Bcl-xL expression was not significantly upregulated by IL-1β and TNF-α.7,14,31 In the present study, we have shown that IL-1β and TNF-α upregulate mRPE pro- and antisurvival genes. It is likely that the relative balance of these factors helps to determine survival of RPE cells. However, the net effect of IL-1β and TNF-α on mouse and hRPE cell survival in mouse models of retinal and/or RPE disease, or human pathology, respectively, remains to be determined.

An important motivation for the present series of experiments was to determine whether mouse tissue and cells could be used as a model for the role of Bcl-xL in hRPE cell survival. Bcl-xL, a crucial member of the Bcl-2 family, was the most highly expressed prosurvival factor gene among those examined in hRPE cells.9 In the present studies, in mRPE cells, Bcl-xL was also the most highly expressed prosurvival factor gene. Other prosurvival factor genes, such as Bcl-x, c-IAP1, c-FLIP, and Traf-1, were also examined and their relative expression patterns were similar to those of hRPE cells.7 Of the antisurvival factor genes, Bax, another key Bcl-2 family member, was also most highly expressed in both mouse and human RPE cells. Bak-1 was expressed at intermediate levels and Bad and Bim at low levels. The similarities between hRPE and mRPE survival factor gene expression patterns suggest that hRPE and mRPE cells behave in a comparable manner and that the role of key survival factor genes, such as Bcl-xL and Bax, is similarly important. Furthermore, expression and regulation by cytokines were generally similar in mouse and human, and functional Bcl-xL inhibition caused similar effects on RPE cell permeability. Taken together, these data support the use of mouse as in vitro and in vivo models to investigate the role of Bcl-2 family members, specifically Bcl-xL and Bax, in human diseases, such as AMD and PVR. We are currently further exploring this approach in our laboratory.

In the current experiments, ASO that inhibited Bcl-xL gene expression and knocked down Bcl-xL protein levels was used to functionally inhibit Bcl-xL. The Bcl-xL gene is highly homologous in mouse and humans.38,39 It has previously been shown that the ASOs used in the current experiments inhibit Bcl-xL in mouse and human hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo,27 and our data further confirm the effect of these ASOs on Bcl-xL in both mouse and human RPE cells. It would be of interest to examine the effect of Bcl-xL in in vivo mouse models of AMD and PVR. However, Bcl-xL knockout mice do not survive past embryonic day 13.5, precluding an analysis of Bcl-xL function at later stages of development.40 We hypothesize that the ASOs used in the present report, given locally to the eye, will be useful to examine the role of Bcl-xL in mouse models of retinal disease.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Eye Institute Grant 930EY05722.

Disclosure: S. Medearis, None; I.C. Han, None; J.K. Huang, None; P. Yang, None; G.J. Jaffe, None

References

- 1. Korte GE, Perlman JI, Pollack A. Regeneration of mammalian retinal pigment epithelium. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;152:223–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunaief JL, Dentchev T, Ying GS, Milam AH. The role of apoptosis in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1435–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:257–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pastor JC. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: an overview. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hiscott P, Sheridan C, Magee RM, Grierson I. Matrix and the retinal pigment epithelium in proliferative retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:167–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charteris DG. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: pathobiology, surgical management, and adjunctive treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:953–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang P, Wiser JL, Peairs JJ, et al. Human RPE expression of cell survival factors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1755–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang P, Tyrrell J, Han I, Jaffe GJ. Expression and modulation of RPE cell membrane complement regulatory proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3473–3481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang N, Peairs JJ, Yang P, et al. The importance of Bcl-xL in the survival of human RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3846–3853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai J, Nelson KC, Wu M, Sternberg P, Jr, Jones DP. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:205–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bazan NG. Survival signaling in retinal pigment epithelial cells in response to oxidative stress: significance in retinal degenerations. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;572:531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bertram KM, Baglole CJ, Phipps RP, Libby RT. Molecular regulation of cigarette smoke induced-oxidative stress in human retinal pigment epithelial cells: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1200–C1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ballinger SW, Van Houten B, Jin GF, Conklin CA, Godley BF. Hydrogen peroxide causes significant mitochondrial DNA damage in human RPE cells. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang P, McKay BS, Allen JB, Roberts WL, Jaffe GJ. Effect of mutant IκB on cytokine-induced activation of NF-κB in cultured human RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1339–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Limb GA, Alam A, Earley O, et al. Distribution of cytokine proteins within epiretinal membranes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:791–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell JD, Cho Y, Foster ML, et al. CpG-containing immunostimulatory DNA sequences elicit TNF-alpha-dependent toxicity in rodents but not in humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2564–2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levine B, Sinha S, Kroemer G. Bcl-2 family members: dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:600–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sorenson CM. Bcl-2 family members and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1644:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vander Heiden MG, Chandel NS, Williamson EK, Schumacker PT, Thompson CB. Bcl-xL regulates the membrane potential and volume homeostasis of mitochondria. Cell. 1997;91:627–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zender L, Hütker S, Mundt B, et al. NFkappaB-mediated upregulation of bcl-xl restrains TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in murine viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berk AJ. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene. 2005;24:7673–7685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang DC, Strasser A. BH3-only proteins: essential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 2000;103:839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parsadanian AS, Cheng Y, Keller-Peck CR, Holtzman DM, Snider WD. Bcl-xL is an antiapoptotic regulator for postnatal CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1009–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luo S, Rubinsztein DC. Apoptosis blocks Beclin 1-dependent autophagosome synthesis: an effect rescued by Bcl-xL. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:268–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yee KS, Wilkinson S, James J, Ryan KM, Vousden KH. PUMA- and Bax-induced autophagy contributes to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1135–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cai X, Conley SM, Naash MI. RPE65: role in the visual cycle, human retinal disease, and gene therapy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009;30:57–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaffe GJ, Earnest K, Fulcher S, Lui GM, Houston LL. Antitransferrin receptor immunotoxin inhibits proliferating human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1163–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geisen P, McColm JR, King BM, Hartnett ME. Characterization of barrier properties and inducible VEGF expression of several types of retinal pigment epithelium in medium-term culture. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu J, Lu W, Reigada D, et al. Restoration of lysosomal pH in RPE cells from cultured human and ABCA4(−/−) mice: pharmacologic approaches and functional recovery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:772–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang P, McKay BS, Allen JB, Jaffe GJ. Effect of NF-kappa B inhibition on TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in human RPE cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2438–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng L, Anderson RE, Agbaga MP, Rucker EB, 3rd, Le YZ. Loss of BCL-XL in rod photoreceptors: increased susceptibility to bright light stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5583–5589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nickells RW, Semaan SJ, Schlamp CL. Involvement of the Bcl2 gene family in the signaling and control of retinal ganglion cell death. Prog Brain Res. 2008;173:423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chu R, Upreti M, Ding WX, Yin XM, Chambers TC. Regulation of Bax by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Bcl-xL in vinblastine-induced apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:241–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Antony R, Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin D1 induces dephosphorylation of Bcl-xL in a PP2A-dependent manner during oxidative stress and promotes retinal pigment epithelial cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18301–18308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang X-c, Jobin C, Allen JB, Roberts WL, Jaffe GJ. Suppression of NF-κB–dependent proinflammatory gene expression in human RPE cells by a proteasome inhibitor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:477–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gautschi O, Tschopp S, Olie RA, et al. Activity of a novel bcl-2/bcl-xL-bispecific antisense oligonucleotide against tumors of diverse histologic origins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang H, Taylor J, Luther D, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide inhibition of Bcl-xL and Bid expression in liver regulates responses in a mouse model of Fas-induced fulminant hepatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Motoyama N, Wang F, Roth KA, et al. Massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 1995;267:1506–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]