Expression of c.119_123dup CRYGC, associated with autosomal dominant human cataracts, causes degeneration and vacuolization of lens fiber cells and cataracts in transgenic mice. This confirms the causative nature of this mutation and suggests that it acts through a direct toxic effect on lens fiber cells.

Abstract

Purpose.

To delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying autosomal dominant congenital cataracts caused by a 5 bp duplication in human CRYGC.

Methods.

c.119_123dup (CRYGC5bpd) and wild-type human γC-crystallin (CRYGC) were expressed in transgenic mouse lenses by the chicken βB1-crystallin promoter. Lenses were characterized histologically, by real-time PCR, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot. pET and Tet-on expression systems were used to express human CRYGC and CRYGC5bpd proteins in Escherichia coliand HeLa cells, respectively.

Results.

Transgenic expression of CRYGC5bpd mutant γC-crystallin results in nuclear cataracts in which lens fiber cells begin to show variable degrees of degeneration and vacuolization by postnatal day 21. By 6 weeks of age all CRYGC5bpd lenses exhibit abnormalities of varying severity, comprising large vacuoles in cortical fiber cells, swelling and disorganization of fiber cells, and defective fiber cell migration and elongation. Levels of CRYGC5bpd mRNA are 3.7- and 14.1-fold higher than endogenous Crygc mRNA in postnatal day 1 and 6-week CRYGC5bpd mice lens, respectively. Crygc, Crygb, Crybb2, and Crybb3 mRNA levels are decreased in CRYGC5bpd mice compared with wild-type and CRYGC mice. Both wild-type and mutant human γC crystallin are uniformly distributed in the cytosol of HeLa cells, but CRYGC5bpd is degraded when expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3).

Conclusions.

Transgenic expression of mutant CRYGC5bpd γ-crystallin at near-physiological levels causes lens opacities and fiber cell defects, confirming the pathogenicity of this mutation. These results further suggest that HCG5pbd γ-crystallin causes cataracts through a direct toxic or developmental effect on lens cells causing damaged microstructure rather than through formation of HMW aggregates with resultant light scattering.

The γ-crystallins, together with α- and β-crystallins, comprise the major water-soluble proteins of the ocular lens.1,2 The crystallins play a critical role in development and the maintenance of lens transparency.3 α-crystallins are synthesized at high levels by epithelial and fiber cells and are expressed first at the lens vesicle stage. Morphologically, the vertebrate lens is composed of the anterior epithelial cells, which cover the anterior surface of the lens, and fiber cells, which are terminally differentiated cells derived from the epithelial cells. The numerous specializations of fiber cells, including elongation, loss of organelles, and synthesis of large amounts of lens crystallins, are critical for the normal clarity and refractive properties of the lens. β-crystallins and γ-crystallins are most highly expressed in lens fiber cells; the γ-crystallins show their highest concentration in the central nucleus, while the β-crystallins generally have their highest concentration in the cortical fiber cells.4

Several mutations in γC-crystallin associated with autosomal dominant cataract have been identified in humans.5 Previously we have demonstrated that a 5-bp insertion in exon 2 of the γC-crystallin gene (c.119_123dup CRYGC) is associated with autosomal dominant variable zonular pulverulent cataracts.6 This mutation is predicted to shift the reading frame of the γC-crystallin coding sequence, resulting in synthesis of a truncated polypeptide consisting of 41 amino acids of the first Greek key motif followed by 63 novel amino acids. Truncation of the polypeptide in the connecting region between the first two motifs would be predicted to destabilize the structure of the first motif, so that no Greek key motifs are expected to be formed correctly. One interesting clinical aspect of these cataracts is the extreme variation in phenotype of individuals carrying the five-base insertion, including both bilateral and unilateral cataracts and ranging from completely asymptomatic adult individuals with no or minimal cataract detected by slit lamp examination to severe congenital total cataracts.7

To elucidate the in vivo effects of human mutant γC-crystallin (CRYGC5bpd) in the eye lens, transgenic mice expressing mutant and wild-type human γC-crystallin under control of a highly efficient lens-specific chicken βB1-crystallin promoter that consistently has been able to drive high-level expression of transgenes in lens fiber cells8 were generated. Expression of CRYGC5bpd results in high levels of mutant mRNA and synthesis of the mutant γC-crystallin, which disrupts normal lens morphology and causes cataract. Furthermore, the high degree of variation in the severity of the cataracts in humans is recapitulated in the transgenic mice, even those originating from the same founder.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Transgenic Mice

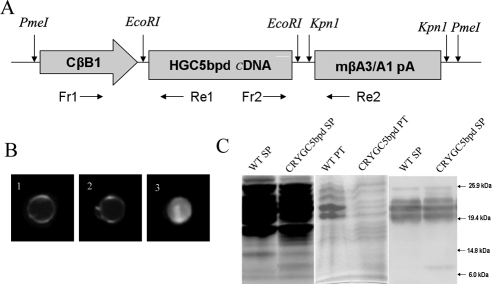

This work abided by the ARVO statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and visual research. The chicken βB1-crystallin/CRYGC5bpd or CRYGC constructs (Fig. 1A) comprised the first 468 bp of the chicken βB1-crystallin promoter followed by the CRYGC or CRYGC5bp cDNA, mouse βA3/A1-crystallin gene splice site, including the last 1055 bp of exon5, intron5, and exon6 and the polyadenylation signal. After confirming the sequence and orientation (Prism 3130 DNA Analysis System; Applied Biosystems [ABI], Foster City, CA) the target fragment was released by PmeI digestion.9 Transgenic mice were generated by pronuclear microinjection of the purified fragments into pronuclear stage inbred FVB/N embryos as described by Wawrousek et al.10 PCR-based screening was used to genotype the mice using primers derived from the chicken βB1-crystallin promoter (Fr1: 5′-CTGGTGGGCTCTGGGGGTAT-3′) and the transgene (Re1: 5′-GCAGGTTGGGGCAGTCAGTG-3′). A 403-bp DNA fragment was amplified and visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. All procedures with mice in this study were performed in compliance with the tenets of the National Institutes of Health Guideline on the Care and Use Animals in Research and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic drawing of the CRYGC5bpd transgene. It was composed of the first 468 bp of the chicken βB1-crystallin promoter followed by the CRYGC or CRYGC5bp cDNA, mouse βA3/A1-crystallin gene splice site including the last 1055 bp of exon5, intron5, and exon6 and the polyadenylation signal. Primers Fr1 and Re1 were used to genotype transgenic mice, and primers Fr2 and Re2 were used for real-time PCR analysis. (B) Gross morphology of lenses from WT, CRYGC, and CRYGC5bpd mice at 20 weeks of age. (1) A WT lens showing no opacity; (2) a CRYGC lens showing no opacity; (3) a CRYGC5bpd lens showing a dense total cataract. The size of CRYGC5bpd lenses were not obviously different compared with WT and CRYGC lenses. (C) Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (left and center) and Western blot analysis (right) of lens proteins from P6W mice. Extracts of water-soluble lens proteins (SP, 40 μg each for coomassie staining; 2 μg each for Western blots) or precipitates (PT, 15 μg each for coomassie staining) were separated by 10–20% gradient SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of mutant γC-crystallin around 10 kDa and endogenous γ-crystallins around 20 kDa.

Morphologic and Histologic Analysis

For gross observation, the lenses from mice at different ages were isolated under a dissecting microscope and photographed by a digital camera (Gel Doc XR System; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For histologic analysis, mouse embryo heads at 15-day (E15D), 1-day (P1D), and 8-day (P8D) postnatal or 21-day (P21D) and 6-week (P6W) postnatal eyes were removed and fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After dehydration and clarification, they were embedded in methyl methacrylate and sectioned serially at 4 μm thickness via the pupil-optic nerve plane, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard histologic technique. The sections were evaluated by light microscope, and then images were obtained by means of a scanning camera equipped with a screening-capture program (Axiocam HRC and AxioVision; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). For transmission electron microscopy, the tissues were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde-formalin. The lenses were embedded in epoxy resin (Ladd LX-112; Ladd Research, Williston, VT). Six 1 μm thick sections stained with toluidine blue were examined under light microscopy. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for examination under a microscope (JEM-100B; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from lenses of different age transgenic and littermate control mice by using a RNA isolation kit (RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), with the addition of DNase I digestion to prevent DNA contamination. Total RNA concentrations were estimated by spectrophotometer at 260 nm, and then cDNA was synthesized (ThermoScript RT-PCR system; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. As described previously,11 primers and probes were designed by commercially available software (Primer Express; ABI) and are shown in Table 1. PCR reactions were performed on a real-time PCR system (Prism 7900HT; ABI). The PCR program consisted of incubation for 2 minutes at 50°C, denaturation for 10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 seconds at 95°C, and 1 minute of annealing and elongation at 60°C. Due to the similarity of gene sequences in this study, sequence analyses were performed to confirm the specific amplicon from each gene. TaqMan MGB probes were used to detect the specific PCR product as it accumulates during PCR. All reactions were performed in a 20 μL reaction volume with 1 ng cDNA template from P1D lens or 10 ng cDNA from P6W. The amount of amplified PCR product was calculated from standard curves. PCR efficiencies of the CRYGC5bpd, Crygc, Crygb, Crybb2, and Crybb3 sequences are all higher than 96%. The housekeeping gene Gapdh served as an endogenous control for quantitation, the absolute amount of each target mRNA being normalized to the amount of Gapdh mRNA.

Table 1.

PCR Primers and Probes Used to Quantify mRNA Levels

| Transcript | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) | MGB Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRYGC5bpd | AACACTACCAATTTCCCATTTTGG | CCTCCATGGTGGTCACACTTC | ACCATCTTCGAGAAAGA |

| Crygc | CATCCCCCATGCAGGTTC | AGCCCGCCTTAGCATCTACA | ATCGCTTCCACCTCAG |

| Crygb | GCCTCATCCCCCAACACTCT | AGAGCCAACTTTGGCATTTG | AGAGGACGGCAGTACC |

| Crybb2 | TGGGCTACGAGCAGGCTAAT | ACGCACGGAAGACACCTTTT | CAGCTTCCATGCCCA |

| Crybb3 | TGAGGCAGAAGTATCCCCAGA | GAGCCCACCTTCTCCAACA | CAGCACGGAGCACC |

| GAPDH | AGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATGTC | TCATGAGCCCTTCCACAATG | CACCAACTGCTTAGCC |

Western Blot Analysis

Whole lenses were harvested from P6W CRYGC5bpd and wild-type (WT) mice and homogenized in 300 μL of lysis buffer containing 1XPBS, 1mM PMSF, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Lysates were then centrifuged at 1400 rpm (MIKRO 200 R; Hettich, Beverly, MA) rotor (18,000g) for 20 minutes at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured (BCA Protein Assay Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL) using BSA as a standard. Equal amounts of water-soluble lens proteins from CRYGC5bpd and WT (40 μg for electrophoresis, 2 μg for Western blot) were mixed with 30 μL buffer containing 2% SDS, 10mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol in 50 mM Tris (pH8.0) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using a 10–20% gradient gel. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:2000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) against mouse γ-crystallin for 2 hours at room temperature. After three 10-minute washes with 1X PBST, AP conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was added as a secondary antibody (1:2000), and samples were incubated for 1 hour, and then washed three times for 10 minutes each with 1X PBST again. Bands were visualized using AP substrate directly on the blot for color development and captured by a digital camera. Each experiment was performed a minimum of three times.

Transformation, Transfection, and Immunolabeling

The cDNA coding region for CRYGC and CRYGC5bpd were subcloned into the Ndel/Xhol and EcoRI/ BamHI sites of the PET-20(b+) (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) and pTRE-Tight vectors (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), respectively, creating the constructs PET-CRYGC/CRYGC5bpd and pTRE-Tight-CRYGC/CRYGC5bpd, which were confirmed by sequencing. Competent BL21(DE3) cells were transformed by PET-CRYGC/CRYGC5bpd. The Escherichia coli cells were grown in LB broth to OD600 = 1 at 37°C with shaking of 250 rpm and then induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 2 hours. The cells were then harvested, and proteins were isolated by sonication.

The Tet-on advanced HeLa cell line (Clontech) was transfected with pTRE-Tight-CRYGC/CRYGC5bpd separately. Cells were cultured in 10 cm plates at a plating density of 1∼1.5 × 106 cells per plate so that the cells would be approximately 90%–95% confluence for transfection. Transfection (Lipofectamine 2000 kit; Invitrogen) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 6 hours incubation, the medium was changed to remove the transfection reagent and DNA, then fresh complete medium was added with Dox at a final concentration of 2 ug/mL to activate expression. Cells were collected after 48 hours, and protein and RNA for Western blot and RT-PCR analysis were isolated (Trizol; Invitrogen).

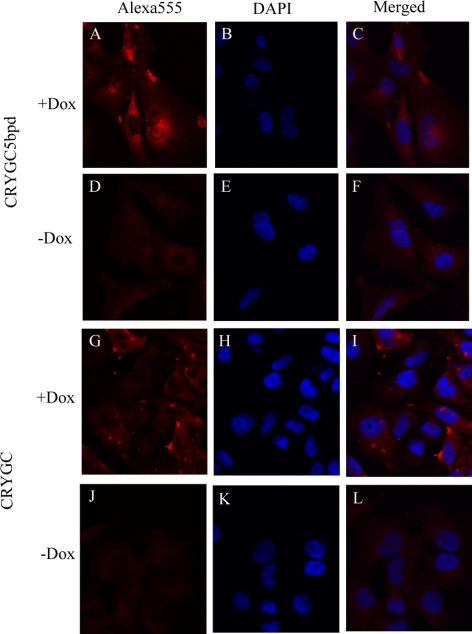

For immunolabeling Tet-on advanced HeLa cells transfected with pTRE-Tight-CRYGC/CRYGC5bpd were cultured in four-well chamber slides. After 48 hours incubation, cells were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS for 10 minutes They were washed three times and then incubated in 0.1 M glycine for 10 minutes, which was replaced with cold blocking buffer for 20 minutes. Blocking buffer was removed, and anti γC rabbit polyclonal antibody 1:400 diluted in ICC buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Tween-20, 0.05% sodium azide in 1X PBS) was added, and the incubation was continued for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing off the first antibody, the cells were incubated in the second antibody, Alexa Fluor 555 goat-anti rabbit IgG (red color) + DAPI (blue color, 1 μg/mL) diluted in cold ICC buffer. Excess buffer was removed, and the cells were covered with Gel-Mount and a coverslip. Images were taken by fluorescence confocal microscopy (LSM 510 laser scanning fluorescence confocal microscope; Zeiss).

Results

Phenotype and Lens Morphology

Expression of the CRYGC5bpd mutant γC-crystallin in transgenic mice resulted in nuclear cataracts of varying severities. Gross morphologic analysis of isolated lenses from P20W CRYGC5bpd mice shows a total cataract with dense opacities in the lens core. However, with respect to opacities and histologic and morphologic abnormalities, lenses from transgenic mice that express wild-type human γC-crystallin are indistinguishable from age-matched nontransgenic control mice (Fig. 1B). The size of CRYGC5bpd lenses is not obviously different from the lenses of CRYGC and WT mice.

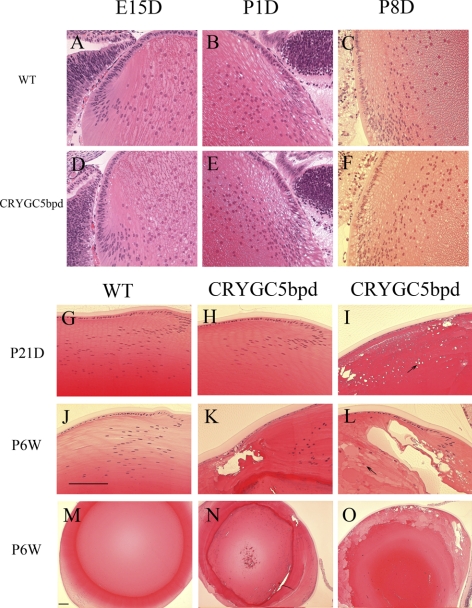

Representative examples of lens histology for CRYGC5bpd mice (OGO2) are shown in Figure 2 and compared against control lenses. Lenses from transgenic CRYGC5bpd mice exhibit normal structure and histology at E15D, P1D, and P8D and are indistinguishable from WT littermates based on their histology (Figs. 2A–F). However, by P21D the lens fiber cells of some mice begin to show variable degrees of degeneration (Fig. 2I). Small vacuoles begin to appear in the equatorial epithelial cells and persist or even increase in size and number in superficial cortical fiber cells (arrow). The severity of the degeneration varies among the mice, and in other CRYGC5bpd P21D mice the lenses show no obvious abnormalities (Fig. 2H). By P6W all lenses from CRYGC5bpd mice exhibit abnormalities, comprising large vacuoles in cortical fiber cells and swollen nucleated fiber cells (bladder cells) with protein-filled lacunae. The fiber cell migration and elongation pattern is found to be defective at the equatorial region and is distinctly different from that observed in WT lenses (Figs. 2K, 2L). The severity of the abnormalities continues to vary among various CRYGC5bpd mice, from extremely severely affected lenses having almost no remaining normal fiber cells (Figs. 2L, 2O) to more mildly affected lenses in which most of the abnormalities are confined to the bow region (Figs. 2K, 2N).

Figure 2.

Histology of lenses from WT (FVB/N strain) and CRYGC5bpd (OGO2) mice of different ages. Lens histology of control mice (A, B, C) is shown for comparison with CRYGC5bpd transgenic mice (D–F). At E15, P1D, and P8D, lenses from CRYGC5bpd mice appear normal (D–F). By P21D small vacuoles begin to appear in the equatorial epithelial cells and superficial cortical fiber cells (arrow; I), whereas some siblings continue to appear normal (H). By P6W all lenses from CRYGC5bpd mice exhibit abnormalities as shown in (K) and (L) comprising large vacuoles in cortical fiber cells and swollen nucleated fiber cells (bladder cells, arrows). However lenses of different mice show varying severity, as shown in (K) and (L) and at a lower magnification (N and O). Scale bar, 50 μm.

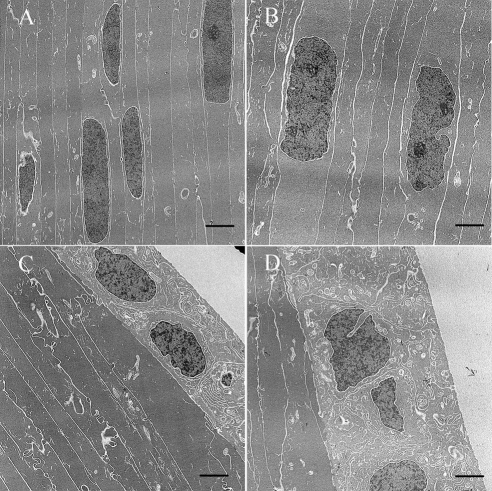

Electron microscopic examination was performed at 5 weeks, just before major disruption of the lens architecture becomes apparent on hematoxylin and eosin stain. There are subtle ultrastructural differences between the control and 5bpd lenses with early bladder cell formation (swollen and nucleated lens fiber cells) in CRYGC5bpd compared with WT lenses (Figs. 3A, 3B) and swelling of the lens epithelial cells in CRYGC5bpd (Figs. 3C, 3D).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopy photo of lenses from WT (FVB/N strain) and CRYGC5bpd mice of 5 weeks. Lens fiber cells from CRYGC5bpd mice (B) appear edematous with prominent nucleoli compared with WT control mice (A). Moreover, lens epithelial cells in CRYGC5bpd are swollen compared with WT (D and C, respectively). Scale bar, 2 μm.

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

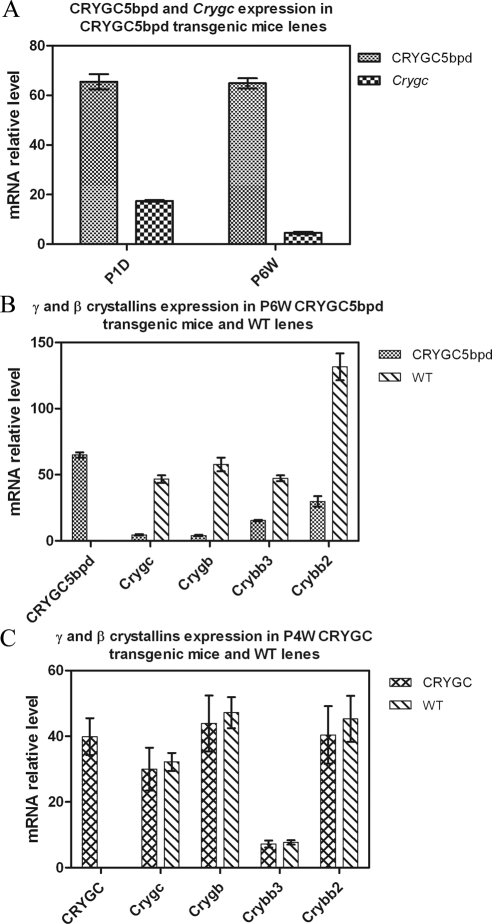

Real-time PCR was performed to determine the expression level of the CRYGC5bpd gene. After normalization against GAPDH in each sample, levels of CRYGC5bpd mRNA in CRYGC5bpd lenses are 3.7-fold higher than those of the endogenous mouse γC-crystallin mRNA at P1D, and 14.7-fold higher at P6W (Fig. 4A; Table 2). To investigate the effect of CRYGC5bpd transgenic expression further, expression of additional genes in the βγ-crystallin family (γB-, βB2-, and βB3-crystallin) were examined in P6W mice. Quantitative RT-PCR reveals that γC- and γB-crystallin mRNAs are decreased by approximately 11.5- and 14.1-fold, respectively, in CRYGC5bpd lenses compared with controls. In addition, there is a similar but somewhat milder decrease of βB2- and βB3-crystallin mRNA levels in CRYGC5bpd relative to control mouse lenses, 4.4- and 3.7-fold, respectively (Table 3; Fig. 4B). However, the level of CRYGC5bpd mRNA in the CRYGC5bpd transgenic mouse lenses is roughly similar to intrinsic crystallin mRNA levels in control mouse lenses, being 139%, 112%, 137%, and 49% of γC-, γB-, βB3-, and βB2-crystallin levels, respectively.

Figure 4.

(A) Comparison of relative mRNA levels of CRYGC5bpd and Crygc in P1D and P6W mice. After normalization to the amount of Gapdh, the relative mRNA level of CRYGC5bpd was 65.5 vs. 17.7, or 3.7-fold more than that of WT Cryg in P1D lens, and 14.7-fold increased over Crygc in P6W lens. (B) Expression of CRYGC5bpd, γC-, γB-, βB3-, and βB2-crystallin in P6W CRYGC5bpd and WT lens. Quantitative PCR shows that γC and γB levels in CRYGC5bpd mice are decreased 11.5- and 14.1-fold, when compared with WT. A similar but milder trend is seen in βB2 and βB3, which are decreased 4.4- and 3.7-fold.

Table 2.

CRYGC5bpd and Crygc mRNA Levels in Lenses of P1D and P6W CRYGC5bpd Mice

| Mouse Lens | CRYGC5bpd/Gapdh | Crygc/Gapdh | CRYGC5bpd/Crygc |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 lens | 65.5 ± 6.92 | 17.5 ± 0.78 | 3.7 |

| 6W lens | 64.9 ± 4.75 | 4.6 ± 1.08 | 14.1 |

Table 3.

Expression of CRYGC5bpd, Crygc, Crygb, Crybb3, and Crybb2 in the Lenses of 6-Week-Old CRYGC5bpd Transgenic and WT Mice

| Strain | CRYGC5bpd/Gapdh | Crygc/Gapdh | Crygb/Gapdh | Crygbb3/Gapdh | Crybb2/Gapdh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRYGC5bpd | 64.9 ± 4.75 | 4.6 ± 1.08 | 4.1 ± 1.12 | 15.4 ± 1.09 | 29.8 ± 8.88 |

| WT | 46.7 ± 4.90 | 57.8 ± 11.34 | 47.4 ± 4.92 | 131.7 ± 22.78 | |

| WT/CRYGC5bpd | 11.5 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 4.4 | |

| CRYGC5bpd mRNA/Cry mRNA | 1.39 | 1.12 | 1.37 | 0.49 |

WT, wild-type.

The expression of human γC-crystallin mRNA (CRYGC), γC-, γB-, βB3-, and βB2-crystallin was also quantitated in 4-week CRYGC transgenic and nontransgenic mice. The mRNA level of CRYGC is similar to those of endogenous γC-, γB-, and βB2-crystallins, but fivefold higher than βB3-crystallin. However, the mRNA levels of endogenous γC-, γB-, βB3-, and βB2-crystallin are very similar in CRYGC and WT mice (Table 4).

Table 4.

Expression of CRYGC, Crygc, Crygb, Crybb3, and Crybb2 in the Lenses of 4-Week-Old Crygc Transgenic and WT Mice

| Strain | CRYGC/Gapdh | Crygc/Gapdh | Crygb/Gapdh | Crygbb3/Gapdh | Crybb2/Gapdh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRYGC | 39.9 ± 5.60 | 30 ± 6.52 | 43.9 ± 8.54 | 7.2 ± 1.06 | 40.4 ± 8.77 |

| WT | 32.2 ± 2.73 | 47.2 ± 4.73 | 7.7 ± 0.68 | 45.3 ± 7.03 | |

| WT/CRYGC | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.12 | |

| CRYGC mRNA/Cry mRNA | 1.24 | 0.85 | 5.18 | 0.88 |

WT, wild-type.

Western Blot Analysis

To investigate whether the transgenic CRYGC5bpd mRNA is effectively translated in the lens, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analyses were carried out on proteins from P6W mice lens. The 5-bp insertion in exon 2 of the human CRYGC results in an amino acid sequence frameshift, giving a new protein comprising the first 41 amino acids of γC-crystallin followed by 62 novel amino acids and a new stop codon. Thus the mutated protein is predicted to be composed of 103 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of 10.7 kDa and a predicted isoelectric point of pH 8.4, compared with the normal γC-crystallin protein, which has a molecular weight of 21 kDa and a PI of 7.1. From the Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE of lens water-soluble extract, a band at approximately 10 kDa is seen only in the CRYGC5bpd lane (Fig. 1C), but not in the control lane, which is identical with the CRYGC transgenic, consistent with the predicted size of mutant CRYGC5bpd protein. The protein profile of the insoluble fractions show some quantitative differences between control and CRYGC5bpd mutant lenses, which have a slight decrease in the intact γ-crystallin bands and some increase in smaller bands, possibly representing degradation products. However, the differences are relatively minor (Fig. 1C). In addition, both insoluble fraction profiles show some additional small bands, probably degradation products, not seen in the soluble fractions. Using a polyclonal antibody against γ-crystallins, the same approximately 10 kDa band is visualized only in the CRYGC5bpd lane. The antibody also recognizes the γ-crystallins around 20 kDa in both the WT and CRYGC5bpd lens extracts as well as a protein of approximately 26 kDa, suggesting that antibody cross-reacts with the β-crystallins to some degree.

Characterization of Recombinant γC-Crystallin in Cells

When E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with the constructs pET-CRYGC and pET-CRYGC5bpd, WT γC-crystallin is expressed exclusively in the soluble fraction, but the CRYGC5bpd mutant protein is degraded, which is detected by Western blot with polyclonal antibodies raised to γ-crystallin (data not shown). To further investigate the influence of mutant CRYGC5bpd γC-crystallin on cell growth and properties, we generated HeLa cells in which expression of exogenous CRYGC and CRYGC5bpd proteins can be induced by Dox treatment using the Tet-on system. Expression of neither CRYGC nor CRYGC5bpd in HeLa or lens epithelial cells had a discernable effect on cell growth or survival (data not shown). Transient transfection of cells with recombinant CRYGC and CRYGC5bpd after 48 hours induction with Dox demonstrated that both WT and CRYGC5bpd γC-crystallin are uniformly distributed in the cytosol of transfected cells, which maintain normal morphology. The intensity of staining is somewhat higher for WT CRYGC than CRYGC5bpd. The γC-crystallin expression in some untreated cells derived from a small amount of leakiness of the Tet promoter in the absence of Dox (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Fluorescence confocal microscopic pictures. The red fluorescence in the first column is Alexa 555 Fluor from the secondary antibody, whereas the nuclei of cells were counterstained with DAPI and are seen blue in second column. The third column shows merged images of both stains. The top two rows show the Tet-on advanced HeLa cells transfected with CRYGC5bpd. γC-crystallins were expressed by adding Dox in (A–C). (D–F) show the transfected cells growing without Dox. The bottom two rows show the WT CRYGC transfectants, Dox-induced expression (G–I) and without Dox γC-crystallins were not expressed (J–L). There is no significant difference between WT and mutant crystallins, although the levels of WT CRYGC appear to be somewhat higher than those of CRYGC5bpd in these experiments.

Discussion

A 5-bp insertion in exon 2 of the γC-crystallin gene (c.119_123dup CRYGC, CRYG5bpd) is associated with autosomal dominant variable zonular pulverulent cataracts.6 To confirm the causative nature of this association and to investigate the mechanism of the c.119_123dup mutation of CRYGC in causing cataracts we examined its expression in transgenic mice in which the CRYGC or CRYGC5bpd mutant cDNA were driven by the chick βB1-crystallin promoter, demonstrated to be efficacious for-high level expression in lens fiber cells.8 Expression of the c.119_123dup mutation of human CRYGC in mice lenses causes cataracts, confirming the causative association of this mutation with cataracts in humans. Although the mutant CRYGC5bpd protein is unstable when expressed in E. coli (data not shown), the CRYGC5bpd lenses contain a new protein immunoreactive with antibody to γ-crystallins and having the molecular weight predicted for the mutant protein. While the mutant γC-crystallin might also be unstable to some degree in lens cells, it is found in the soluble fraction of transfected HeLa cells and a lens homogenate, and the mechanism of cataractogenesis appears to involve a toxic effect on the lens fiber cells with consequent disruption of normal lens morphology.

Transgenic mice expressing the c.119_123dup mutation of human CRYGC recapitulate the phenotype seen in the family described by Basti et al.12 quite well. In general, both human and mouse cataracts associated with mutations in γ-crystallins show a common phenotype of nuclear or lamellar cataract, and the mouse model also resulted in nuclear cataracts. Interestingly, at least some γ-crystallin mutants in humans maintain their protein fold but show abnormal aggregation13 or outright crystallization.14 In the mouse model, cataracts have been shown to result from both light scattering by protein aggregates15 and degradation of lens fiber cells.16 Comprehensive reviews of mouse17 and human5 cataracts have been published recently with a related online database.

One notable feature is the late stage at which lens opacities develop, and another is the variability of age of onset and severity of the cataracts among transgenic mice. This variability existed even among mice having the same founder and thus identical insertion sites for the transgene, and presumably similar expression levels. In spite of the high levels of expression of the transgene both before and after birth, lens defects were detected in transgenic mice beginning at 3 weeks of age, and as late as 6 weeks in some mice. Similarly, in some mice expression of the transgene caused degeneration of cells over a large part of the lens accompanied by large protein-filled lacunae and even rupture of the lens, while in others the degeneration was milder with fewer lacunae and with cellular degeneration limited to the bow and superficial nuclear region. This variable severity and onset is similar to the human phenotype, with some family members being completely asymptomatic and having mild or no opacity on slit lamp examination, while others presented with severe congenital cataracts. The variable severity of the phenotype in this inbred strain of transgenic mice raised in a controlled environment cannot be explained by modifying genes or environmental influences but suggests that a stochastic process might be responsible for the phenotypic variability. One attractive possibility is that it might relate to variable efficiency of nonsense-mediated decay of the mutant.

These results also confirm the high activity of the chicken βB1-crystallin promoter in transgenic mice as previously reported.18,19 The mRNA from the pCBB1CRYGC5bpd construct is expressed in the lens at levels roughly similar to the endogenous βγ-crystallins and is sufficiently well translated to cause cataracts. This is in contrast to transgenic mice generated previously using the 425 bp αA-crystallin promoter with an SV40 t-antigen splice site, which did not develop cataracts (data not shown). While the protein product is easily seen on acrylamide gels, the levels appear to be somewhat lower than those of endogenous crystallins, although they were not estimated precisely. This might be due to increased turnover related to the expected instability of the mutant protein relative to endogenous γ-crystallins.

The highly vacuolated, degenerative lens fiber cells and abnormal lens architecture in CRYGC5bpd mice could be explained by a toxic effect of the CRYGC5bpd protein. We know different βγ-crystallin mutants may show different unique phenotypes, but the mutant proteins often form large aggregates, which then cause light scatting in the lens with preservation of normal lens morphology.20 However, the pathogenesis of the cataracts in CRYGC5bpd transgenic mice is not due primarily to light scattering by protein precipitates. Rather the protein appears to be toxic to the cells of the lens as demonstrated by bladder cell formation and vacuolization on histology and ultrastructure. The degeneration begins in the equatorial epithelia and reaches a maximum in the cortical fiber cells, consistent with the activity of the βB1-crystallin promoter.8,19 This process eventually culminates in severe disruption of the lens architecture with the formation of large lacunae containing clumps of proteinaceous debris, particularly in the bow region. In most cases epithelial cell changes overlie severely affected areas of the nucleus, suggesting the possibility of a secondary effect. An interesting alternative is that expression of the mutant γC-crystallin might interfere with fiber cell elongation and development, with secondary degeneration of the aberrant cells, although there are no data to support this possibility over a direct toxic effect.

The reduction in mRNA levels of endogenous βγ-crystallins initially might suggest a regulatory effect of the CRYGC5bpd protein. However, the reduction of mRNA level of endogenous γβ-crystallins in CRYGC5bpd transgenic mice also could be explained by the toxic effect of the CRYGC5bpd protein. Degeneration of cortical and central fiber cells would exert an extreme effect on mRNA stability, causing the remarkable decrease of mRNA levels of γC-, γB-, βB2-, and βB3-crystallin seen in the CRYGC5bpd lenses. However, levels of these mRNAs are similar in the lenses of mice transgenic for CRYGC and WT mice (Table 3; Table 4), which argues against feedback of the γC-crystallin protein or mRNA on endogenous crystallin transcription. In lenses transgenic for WT CRYGC the levels of the transgenic mRNA are similar to those of the endogenous β- and γ-crystallins (Table 4), although the human and mouse γC-crystallin could not be distinguished on gel electrophoresis. Finally, the γ-crystallins tend to be expressed more specifically in the central embryonic and fetal nuclear fiber cells than the β-crystallins, which are also expressed in the equatorial epithelia and cortical fiber cells, and this could explain their greater decrease in CRYGC5pbd mouse lenses.

The most obvious early effect of CRYGC5bpd overexpression is variable vacuolization of lens fiber cells, followed by degeneration of the cortical fiber cells (bladder cell formation) resulting in large lacunae with proteinaceous debris, suggesting a toxic effect of the mutant protein on lens fiber cells. In contrast, transfection of HeLa cells with recombinant CRYGC and CRYGC5bpd after a 48-hour induction with Dox showed no obvious deleterious effect on the cells, and both WT and CRYGC5bpd γC-crystallin were uniformly distributed in their cytosol but not their nuclei. While we do not have a definitive explanation, this might represent either greater sensitivity of the lens cells to the mutant crystallin or a mitigating dilutional effect of cell growth in the HeLa cells. Taken together, these data suggest that the CRYGC5bpd crystallin mutant protein causes cataract through a toxic effect on lens fiber cells, thus disrupting the cellular architecture and order rather than by aggregating and precipitating within otherwise normal fiber cells and then scattering light, although a combination of both mechanisms cannot be excluded.

In summary, these results demonstrated that abnormal lens phenotype was developed by overexpression of mutant CRYGC5bpd on the background of WT endogenous mouse crystallins, including γC-crystallin. This confirms the association of this mutation with cataracts in humans. The mechanism of cataract formation appears to be a toxic effect of the CRYGC5bpd crystallin mutant protein affecting the growth and organization of lens fiber cells and eventually causing cellular degeneration, rather than primarily causing cataract by aggregating and precipitating and then scattering light.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Eye Institute Intramural Program.

Disclosure: Z. Ma, None; W. Yao, None; V. Theendakara, None; C.-C. Chan, None; E. Wawrousek, None; J.F. Hejtmancik, None

References

- 1. Wistow G. Evolution of a protein superfamily: relationships between vertebrate lens crystallins and microorganism dormancy proteins. J Mol Evol. 1990;30:140–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ray ME, Wistow G, Su YA, Meltzer PS, Trent JM. A1M1, a novel non-lens member of the beta-gamma-crystallin superfamily associated with the control of tumorigenicity in human malignant melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3229–3234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hejtmancik JF, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Piatigorsky J. Molecular biology and inherited disorders of the eye lens. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Sly WS, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease, 8nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001:6033–6062 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Graw J. The crystallins: genes, proteins and diseases. Biol Chem. 1997;378:1331–1348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shiels A, Bennett TM, Hejtmancik JF. Cat-Map: putting cataract on the map. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2007–2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ren Z, Li A, Shastry BS, et al. A 5-base insertion in the γC-crystallin gene is associated with autosomal dominant variable zonular pulverulent cataract. Hum Genet. 2000;106:531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott MH, Hejtmancik JF, Wozencraft LA, et al. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract: interocular phenotypic heterogeneity. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:866–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taube JR, Gao CY, Ueda Y, et al. General utility of the chicken betaB1-crystallin promoter to drive protein expression in lens fiber cells of transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 2002;11:397–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li A, Jiao X, Munier FL, et al. Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy is caused by mutations in the novel gene CYP4V2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:817–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wawrousek EF, Chepelinsky AB, McDermott JB, Piatigorsky J. Regulation of the murine alpha A-crystallin promoter in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1990;137:68–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riazuddin SA, Yasmeen A, Yao W, et al. Mutations in βB3-crystallin associated with autosomal recessive cataract in two Pakistani families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2100–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Basti S, Hejtmancik JF, Padma T, et al. Autosomal dominant zonular cataract with sutural opacities in a four-generation family. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pande A, Ghosh KS, Banerjee PR, Pande J. Increase in surface hydrophobicity of the cataract-associated P23T mutant of human gammaD-crystallin is responsible for its dramatically lower, retrograde solubility. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6122–6129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pande A, Pande J, Asherie N, et al. Crystal cataracts: human genetic cataract caused by protein crystallization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6116–6120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang K, Cheng C, Li L, et al. GammaD-crystallin associated protein aggregation and lens fiber cell denucleation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3719–3728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graw J, Neuhauser-Klaus A, Klopp N, et al. Genetic and allelic heterogeneity of Cryg mutations in eight distinct forms of dominant cataract in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1202–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graw J. Mouse models of cataract. J Genet. 2009;88:469–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan MK, Roth HJ, Thompson M, Kantorow M, Piatigorsky J. Chicken beta B1 crystallin: gene sequence and evidence for functional conservation of promoter activity between chicken and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:68–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen WV, Hejtmancik JF, Piatigorsky J, Duncan MK. The mouse betaB1-crystallin promoter: strict regulation of lens fiber cell specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1519:30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu H, Du X, Wang M, et al. Crystallin {gamma}B-I4F mutant protein binds to {alpha}-crystallin and affects lens transparency. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25071–25078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]