Abstract

Chiasmata resulting from interhomolog recombination are critical for proper chromosome segregation at meiotic metaphase I, thus preventing aneuploidy and consequent deleterious effects. Recombination in meiosis is driven by programmed induction of double strand breaks (DSBs), and the repair of these breaks occurs primarily by recombination between homologous chromosomes, not sister chromatids. Almost nothing is known about the basis for recombination partner choice in mammals. We addressed this problem using a genetic approach. Since meiotic recombination is coupled with synaptonemal complex (SC) morphogenesis, we explored the role of axial elements – precursors to the lateral element in the mature SC - in recombination partner choice, DSB repair pathways, and checkpoint control. Female mice lacking the SC axial element protein SYCP3 produce viable, but often aneuploid, oocytes. We describe genetic studies indicating that while DSB-containing Sycp3−/− oocytes can be eliminated efficiently, those that survive have completed repair before the execution of an intact DNA damage checkpoint. We find that the requirement for DMC1 and TRIP13, proteins normally essential for recombination repair of meiotic DSBs, is substantially bypassed in Sycp3 and Sycp2 mutants. This bypass requires RAD54, a functionally conserved protein that promotes intersister recombination in yeast meiosis and mammalian mitotic cells. Immunocytological and genetic studies indicated that the bypass in Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− oocytes was linked to increased DSB repair. These experiments lead us to hypothesize that axial elements mediate the activities of recombination proteins to favor interhomolog, rather than intersister recombinational repair of genetically programmed DSBs in mice. The elimination of this activity in SYCP3- or SYCP2-deficient oocytes may underlie the aneuploidy in derivative mouse embryos and spontaneous abortions in women.

ANEUPLOIDY is the major cause of birth defects and chromosome abnormalities in humans (Hassold et al. 2007). Most are traceable to meiosis I (MI) errors during oogenesis. Erosion of homologous chromosome cohesion is one contributor to age-related increases in oocyte aneuploidy (Chiang et al. 2010). Additionally, in most organisms, crossing over is essential to ensure accurate segregation of homologous chromosome pairs at the first meiotic division. Cohesin-stabilized chiasmata physically tether homologous chromosomes, contributing to their eventual congression to, and coalignment at the metaphase plate (Hodges et al. 2005; Tachibana-Konwalski et al. 2010). There, the pair is held in balance by opposing forces: centromere cohesion and chiasmata maintaining attachment on one hand vs. spindle fibers pulling each homolog toward opposite poles. The absence of a crossover (CO) between any chromosome pair can result in random disjunction and aneuploidy, potentially leading to embryonic death or birth defects. How meiocytes create and distribute COs among all chromosomes has been a longstanding subject of research.

In mice, pairing and synapsis of homologs is dependent upon homologous recombination (HR). HR is induced by the genetically programmed creation of >200 double strand breaks (DSBs) in the genome (Plug et al. 1996). The distribution of DSBs is not entirely random, and is influenced by DNA sequence, chromatin structure/epigenetic state, and trans-acting factors (Getun et al. 2010; Parvanov et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2010). The SPO11-induced DSBs trigger a meiotic DNA damage response, whereby key proteins such as the ATM sensor kinase initate a signaling cascade (including H2AX phosphorylation and p53 activation) that recruits HR proteins to repair the breaks (Burgoyne et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2010). DSB repair eventually yields noncrossover (NCO) and CO events, with the former being favored in an ∼10:1 ratio in mice (Anderson et al. 1999; Koehler et al. 2002). The CO and NCO pathways are temporally and mechanistically distinct both in yeast (Allers and Lichten 2001; Hunter and Kleckner 2001; Borner et al. 2004; Cromie and Smith 2007) and (probably) mice (Guillon et al. 2005).

As in mitotic cells, meiocytes have surveillance systems (“checkpoints”) to monitor DSB repair (Roeder 1997; Ghabrial and Schupbach 1999; Bhalla and Dernburg 2005). Defects in recombination and/or chromosome synapsis trigger delay or arrest in the pachytene stage of prophase I. This response to meiotic defects is often referred to as the “pachytene checkpoint” (Roeder and Bailis 2000). Persistence of checkpoint-sensed defects can result in gamete apoptosis. These systems are important for preventing the transmission of genetic aberrations to offspring.

The pachytene checkpoint monitors two aspects of meiotic chromosome metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans: DSB repair and chromosome synapsis (Bhalla and Dernburg 2005; Wu and Burgess 2006). Genetic analyses indicate that mice also have distinct DNA damage and synapsis monitoring/response pathways. Spermatocytes homozygous for a hypomorphic allele (Trip13Gt) of the yeast Pch2 ortholog exhibit complete homolog synapsis, but undergo pachytene arrest and death due to incomplete DSB repair (Li and Schimenti 2007; Roig et al. 2010). SPO11 deficiency, in which meiocytes lack DSBs, also triggers elimination of both oocytes and spermatocytes due to asynapsis (Baudat et al. 2000; Romanienko and Camerini-Otero 2000). The distinction in surveillance/checkpoint pathways is also evident by the timing by which mutant oocytes are eliminated. DSB repair-defective mutant oocytes (e.g., Dmc1, Msh5, and Trip13Gt) undergo elimination by birth before follicle formation, reflecting a rigorous pachytene DNA damage checkpoint (we will subsequently refer to it as such) identical to that in spermatocytes. To the contrary, strictly asynaptic mutants (Spo11 and Mei1) can form follicles after birth at ∼15–20% the WT level, and oocytes contained therein can persist and mature for weeks after birth (Di Giacomo et al. 2005; Reinholdt and Schimenti 2005).

Whereas elimination of oocytes with severely defective synaptonemal complexes (SCs) is mediated by the scHop1 ortholog HORMAD1 (Daniel et al. 2011), the “synapsis checkpoint” in males may not be a checkpoint per se; rather, it appears to be a consequence of disrupted meiotic sex chromosome inactivation (MSCI), which is common in highly asynaptic spermatocytes (Mahadevaiah et al. 2008; Royo et al. 2010). The mammalian meiotic DNA damage checkpoint pathway components are not well delineated. TRP53 is activated in response to SPO11-induced DSBs in spermatocytes (Lu et al. 2010), but it is not yet known whether this pathway is responsible for elimination of spermatocytes with unrepaired DSBs.

Not only must meiocytes repair their DSBs to avoid checkpoint-mediated elimination, but also the template used for homologous recombination repair is crucial. In 4C mitotic cells, there is a strong preference for repairing DSBs using the sister chromatid as template (Kadyk and Hartwell 1992; Stark and Jasin 2003), likely a consequence of their physical association. Since the “purpose” of SPO11-induced DSBs in meiosis is to stimulate recombination between homologous chromosomes, which is ultimately critical for proper disjunction at the first meiotic division, mechanisms have evolved to overcome the predilection for intersister (IS) DSB repair such that recombination between homologs is predominant (Jackson and Fink 1985). Observations in yeast led to the idea that there is a “barrier to sister chromatid recombination” that suppresses IS recombination to favor recombination between homologs (Niu et al. 2005). Nevertheless, despite the suppression by such a barrier, intersister meiotic recombination occurs at substantial rates (Schwacha and Kleckner 1997; Goldfarb and Lichten 2010). However, the proportion of DSBs that undergo IS recombination is inhibited so as to enable sufficient amounts of interhomolog (IH) repair (Lao and Hunter 2010).

In S. cerevisiae, elements of both the DNA damage checkpoint and the SC influence DSB repair partner choice. The SC is a tripartite structure that defines synapsis and consists of a proteinaceous central element flanked by two chromosome-bound lateral elements. The precursors of lateral elements are called axial elements, and they form before, and as a prerequisite to, mature SC assembly and synapsis. Deletion of yeast genes encoding the axial element proteins Red1 or Hop1 allow repair of DSBs in the absence of the meiosis-specific RecA homolog Dmc1, which is otherwise essential for homologous recombination repair of DSBs and synapsis in yeast and mice (Schwacha and Kleckner 1997; Xu et al. 1997; Pittman et al. 1998; Yoshida et al. 1998; Bishop et al. 1999; Carballo et al. 2008). Although Red1 or Hop1 deficiency allows bypass of meiotic arrest in dmc1 yeast, thus resembling the consequences of an ablated checkpoint, the rescue actually occurs because intersister recombination is activated to repair the DSBs (Niu et al. 2005). In yeast, the ability to monitor recombination intermediates on 2D gels and to exploit unique mutants that facilitate such analyses (for example, which allow meiosis to occur in haploid cells or which block processing of DSBs) allow direct detection of intersister and interhomolog recombination intermediates.

In mammals, it is assumed but not formally known that a bias to interhomolog repair of meiotic DSBs exists. The complex nature of mammalian gametogenesis greatly hinders the search for genes that might be involved in this process, and strategies such as unbiased genetic screening would be extraordinarily difficult. As an alternative, we drew on the yeast knowledge to hypothesize that axial element proteins in mice might play a role in recombination partner choice or checkpoint function. Here, we report that eliminating either of two such proteins, SYCP2 and SYCP3, rescues early elimination of recombination-defective oocytes and that this rescue is dependent on RAD54, a protein required for intersister recombination in yeast. We hypothesize that SC axial elements promote interhomolog recombination at the expense of intersister exchange.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The mouse alleles were as follows: Dmc1, Dmc1tm1Jcs (Pittman et al. 1998); Spo11, Spo11tm1Sky (Baudat et al. 2000); Sycp3, Sycp3tm1Hoog (Yuan et al. 2000); Rec8, Rec8mei8 (Bannister et al. 2004); Trip13, Trip13Gt(RRB047)Byg (Li and Schimenti 2007); Rad54, Rad54ltm1Jhjh (Essers et al. 1997); Prkdc, Prkdcscid; Ccnb1ip1, Ccnb1ip1mei4 (Ward et al. 2007); Mei1, Mei1m1Jcs (Libby et al. 2003); Sycp2, Sycp2tm1Jw (Yang et al. 2006); and Atm, Atmtm1Led (Elson et al. 1996). Genotyping was performed as described in the original publications of these mutations, or in the case of Scid mice, according to The Jackson Laboratory’s recommended PCR assay. The diverse origins of the mice necessitated the use of mixed backgrounds. Most of the strains maintained in the colony were bred into the C57BL/6J background, but others contain proportions of FvB, 129, and C3H. Comparisons of compound mutants and controls involving a key mutation (e.g., Trip13 + Sycp3) utilized siblings or pups from the same or related parents.

Histology and oocyte quantification

Testes or ovaries were fixed in Bouin’s, embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned at 5 μm, and stained by hematoxylin and eosin. The ovaries were taken from females that were 3 weeks old, ±2 days. For oocyte quantification, every fifth section was scored for the presence of the following classes of oocytes: primordial, primary, secondary, preantral, and antral, using the criteria of Myers et al. (2004). Only those with a visible nucleus were counted. These five categories were grouped into two (primordial and the remaining four categories) for reporting in Figure 2. Note that this method underestimates total oocyte numbers; thus, the oocyte counts reported in Figure 2 are intended for intergenotype comparisons.

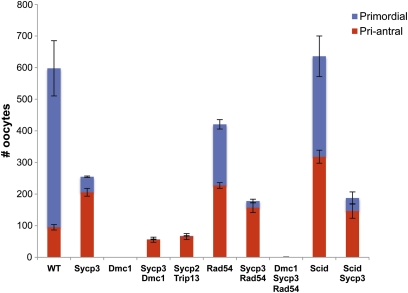

Figure 2 .

Oocyte counts from mutant genotypes. For each genotype category listed at the bottom, presence of the gene names refers to homozygosity for the mutant allele. The red-coded class (“pri-antral”) represents the sum of primary, secondary, preantral, and antral oocytes. Error bars = SEM. N ≥ 4 ovaries for all genotypes. The wild type (WT) samples (N = 6) included heterozygote littermates of mutants.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunolabeling of surface-spread spermatocytes and newborn oocytes was performed as described (Bannister et al. 2004; Reinholdt et al. 2004). To reach conclusions on the pattern of staining for various proteins, 30 (unless otherwise indicated) well-spread nuclei of particular meiotic stages were first identified under the fluorescent microscope on the basis of SYCP3, SYCP1 or STAG3 staining, then imaged at both appropriate wavelengths to determine the pattern of second proteins with focal patterns such as γH2AX, RAD51 or RPA. Unless otherwise indicated, the panels shown in the figures were the exclusive or predominant patterns seen.

Primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: rabbit anti-SYCP1 (1:1,000; a gift from C. Heyting) (Meuwissen et al. 1992); mouse anti-γH2AX (1:500, JBW301 Upstate Biotechnology); rabbit anti-STAG3 (1:1,000; a gift from R. Jessberger); guinea pig anti-STAG3 (1:500; a gift from C.Hoog); rabbit anti-RAD51 (1:250; Calbiochem); and rabbit anti-RPA (1:250; a gift from C. Ingles). All secondary antibodies conjugated with either Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Molecular Probes) were used at a dilution of 1:1000. All images were taken with a 60X or 100x objective lens (the latter under immersion oil). Graphs and statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism5. Focus number comparisons between genotypes were evaluated using the non-parametric one-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Results

Genetic analyses indicate that Sycp3−/− oocytes have an intact DNA damage checkpoint and repair their meiotic DSBs

Spermatocytes lacking SYCP3 undergo arrest and apoptosis in meiotic prophase I as a result of defective chromosome synapsis (Yuan et al. 2000). About 2/3 of mutant diplotene oocytes in perinatal Sycp3−/− females exhibit markers of DNA damage (RAD51/DMC1, γH2AX, and RPA), and only about 1/3 of Sycp3−/− oocytes survive (albeit with elevated aneuploidy) in adult ovaries (Wang and Hoog 2006). While it is not certain if the surviving oocytes are those that have repaired meiotically-induced DSBs [which occur at roughly normal amounts in males as judged by RAD51 focus formation (Yuan et al. 2000)], the results suggest that SYCP3 normally promotes conditions for DSB repair and crossing over (Wang and Hoog 2006). Loss of that fraction of Sycp3−/− oocytes that do die, particularly those with aneuploidy, occurs by 8 dpp. This prompted Wang and Hoog to propose that the DNA damage checkpoint eliminated them (Wang and Hoog 2006). However, DSB-repair defective mutations like Dmc1, Trip13, Rec8 and Msh5 are subject to the rigorous pachytene DNA damage checkpoint (discussed earlier) that eliminates oocytes shortly after birth before follicle formation (Bannister et al. 2004; Di Giacomo et al. 2005; Li and Schimenti 2007), thus constituting a temporal inconsistency.

We considered two possible explanations for the substantial survival and fertility of Sycp3−/− oocytes in ovaries that also eliminate, in a delayed manner, the fraction of oocytes (2/3) that presumably are those that retained DNA damage at birth. One is that SYCP3 is a component of the DNA damage checkpoint, and its absence allows some Sycp3−/− oocytes to escape embryonic meiotic arrest and neonatal apoptosis to allow for subsequent DSB repair. This subset of oocytes would have had extra time to repair DSBs and gain the ability to generate viable offspring. The second possibility is that while meiotic DSBs in the neonatally-surviving oocytes were repaired in an SYCP3-independent manner before checkpoint-mediated elimination, most underwent a degree of repair that was insufficient for viability but sufficient to postpone neonatal death for several days (to 8 dpp).

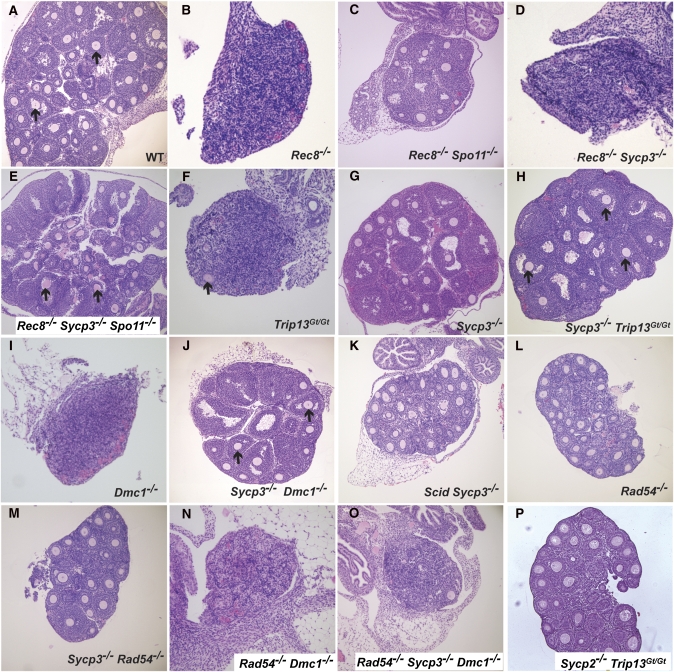

To distinguish between these possibilities, we adopted a genetic approach that involved epistasis analyses of several meiotic mutants. If the DNA damage checkpoint is compromised in Sycp3−/− oocytes, then the absence of SYCP3 should rescue other DSB repair defective mutants. REC8 is a meiosis-specific cohesin that is required for fertility in both sexes. Rec8 mutant spermatocytes show precocious separation of sister chromatids and persistent markers of DSBs (Bannister et al. 2004), consistent with reduced homologous recombination (HR) repair as in S. pombe (De Veaux et al. 1992). Young mutant females have residual ovaries that are devoid of follicles (Figure 1B) (Bannister et al. 2004), indicative of DNA damage checkpoint-mediated oocyte elimination (Di Giacomo et al. 2005). Spo11 deletion rescued the oocyte loss, supporting this interpretation (Figure 1C), but Sycp3 deletion did not (Figure 1D). This was not a consequence of an undefined synthetic interaction between the Sycp3 and Rec8 mutations, as Spo11 deletion restored oocyte survival in Rec8−/− Sycp3−/− Spo11−/− triple mutants (Figure 1E), thus indicating that DNA damage triggers oocyte loss in Rec8−/− Sycp3−/− mutants. Similarly, mutation of Sycp3 did not rescue Atm−/− oocytes (data not shown), which also undergo pachytene checkpoint elimination in a Spo11-dependent manner (Di Giacomo et al. 2005). The robust oocyte elimination in Atm−/− Sycp3−/− and Rec8−/− Sycp3−/− females indicates that the DNA damage checkpoint is not compromised in Sycp3−/− oocytes, consistent with what was suggested (Wang and Hoog 2006). Furthermore, this implies that viable oocytes in Sycp3−/− adults underwent adequate repair of meiotic DSBs before execution of the DNA damage checkpoint.

Figure 1 .

Ovarian histology of meiotic mutants. Shown are hematoxylin and eosin stained ovaries of 18- to 23-day-old mouse ovaries. Genotypes are indicated in an abbreviated fashion; the actual allele names are given in Materials and Methods. Arrows point to oocytes in developing follicles. Note that the oocyte is often out of the section plane in many follicles. At least three animals of each genotype were examined, with consistent qualitative results in all cases.

The meiotic DSB repair proteins TRIP13 and DMC1 become nonessential for oocyte survival in the absence of SYCP3

To identify the means by which Sycp3−/− oocytes conduct DSB repair, we constructed compound mutants between Sycp3 and other genes that disrupt particular repair pathways. Trip13 is required for meiotic DSB repair and IH recombination in mice (Li and Schimenti 2007; Roig et al. 2010). The Trip13Gt(RRB047)Byg allele (abbreviated Trip13Gt) appears to affect primarily NCO recombination, causing meiotic arrest and infertility in both sexes (Li and Schimenti 2007). Trip13Gt/Gt oocytes undergo death around the time of birth, prior to follicle formation, indicative of the pachytene DNA damage checkpoint-mediated elimination (Di Giacomo et al. 2005). As reported previously (Li and Schimenti 2007), C57BL/6J-Trip13Gt/Gt ovaries (3 weeks old) are severely dysplastic due to complete absence of primordial and primary follicles and complete or nearly complete absence of more developed follicles (Figure 1F; N = 4 ovaries from two females had zero follicles; N = 2 ovaries from one female had a total of four). This stands in contrast to WT or Sycp3−/− ovaries (Figure 1, A and G), which have hundreds (Figure 2). The ovarian and follicular agenesis of Trip13Gt/Gt oocytes is dependent upon SPO11 and MEI1, two proteins required for meiotic DSB formation, indicating that oocyte death is triggered by defects in DSB repair (Li and Schimenti 2007). Surprisingly, Sycp3 deletion rescued the near-complete elimination of Trip13Gt/Gt oocytes, as visualized by the presence of numerous developing follicles in the doubly mutant ovaries (Figure 1H). However, primordial follicles were conspicuously absent; these are also depleted severalfold in Sycp3 single mutants compared to WT (Figure 2). Despite the presence of the growing follicles, Trip13Gt/Gt, Sycp3−/− females were infertile (N = 3; they failed to produce any litters after several months mating to fertile males).

Because Trip13Gt/Gt mutants allow chromosome synapsis and thus progression to pachynema (in spermatocytes) before being eliminated due to persistent DSBs, we tested whether deletion of Sycp3 could rescue a more severe recombination mutant, a Dmc1 null. Dmc1−/− meiocytes fail to conduct homologous recombination repair (HRR) of DSBs, leading to zygotene/pachytene elimination that can be alleviated (in oocytes) by genetically abrogating meiotic DSBs (Pittman et al. 1998; Di Giacomo et al. 2005; Reinholdt and Schimenti 2005). Histology of ∼3-week-old postnatal Dmc1−/− Sycp3−/− ovaries revealed a rescue of the absolute oocyte depletion and ovarian agenesis characteristic of Dmc1 single mutants (Figure 1, I and J). The rescue was incomplete, as the primordial oocyte pool was essentially depleted, and the more developed pool (primordial–antral stages) was lower than in WT and Sycp3 single mutants (Figure 2).

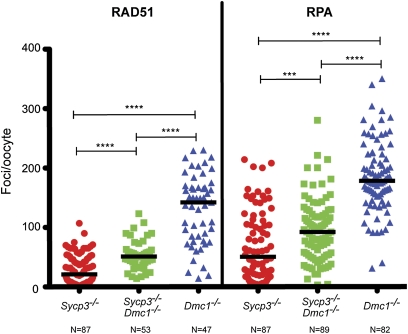

If the survival of Dmc1−/− Sycp3−/− oocytes was enabled by enhanced DSB repair, we would expect a decrease of damage markers compared to Dmc1 single mutants. To test this, surface spread nuclei from newborn oocytes were immunostained for RAD51 and RPA, recombination proteins that form detectable foci at DSB sites during early and intermediate stages of meiotic DSB repair. Indeed, median numbers of RAD51 and RPA foci were significantly lower in Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− oocytes vs. Dmc1−/−, though higher than in Sycp3−/− oocytes (Figure 3; supporting information, Figure S3). These data indicate that an alternative, DMC1-independent DSB repair pathway(s) is activated in SYCP3-deficient oocytes, but that the DMC1 pathway remains functional unless disrupted.

Figure 3 .

Immunocytological evidence that SYCP3 deficiency increases DSB repair in Dmc1 null oocytes. Plotted are numbers of foci/oocyte for the indicated markers (RAD51 or RPA) in surface-spread chromosomes of newborn oocytes. Each represents a single oocyte. The indicated number of oocytes were scored, and these oocytes were obtained from three pups/genotype. Black horizontal lines in the graph indicate median values. Asterisks represent the significance levels (by Mann–Whitney test): ***P = 0.0004; ****P < 0.0001.

One such alternative DMC1-independent pathway could be interhomolog CO recombination which, as indicated earlier, occurs at a much lower rate than NCO recombination in mice. However, mice lacking Ccnb1ip1, which is required for CO recombination specifically (Ward et al. 2007), did not negatively impact survival of Sycp3−/− oocytes (not shown). To test the possibility that nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) is hyperactivated to repair meiotic DSBs in Sycp3−/− oocytes, double mutants with Prkdc (Scid) were constructed. This genotype did not ablate oocyte survival either (Figure 1K; Figure 2).

In summary, in the absence of an intact SC (SYCP3 deficiency), a state triggering arrest and apoptosis in spermatocytes (Yuan et al. 2000), IH recombination is no longer absolutely essential for all or most meiotic DSB repair in oocytes. Additionally, NHEJ does not appear to be responsible for DSB repair and survival of Sycp3−/− oocytes. The question then becomes: What DSB repair pathway is adopted by Sycp3−/− oocytes?

Genetic evidence that SYCP3 governs recombination partner choice

In S-G2 mitotic cells, DSBs are repaired preferentially via IS recombination, where proximity and cohesion of sister chromatids predisposes to this outcome (Kadyk and Hartwell 1992; Stark and Jasin 2003; Watrin and Peters 2006). It has been hypothesized that in many species [including budding yeast (Schwacha and Kleckner 1997), but possibly to a lesser degree in fission yeast (Cromie et al. 2006)], the barrier to sister chromatid recombination (BSCR) overcomes this preference in order to drive IH recombination and thus ensure proper disjunction at MI. Alternatively or in addition, there may exist an active stimulus of IH repair at the expense of IS recombination, as suggested for Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Latypov et al. 2010).

Since SYCP3 is required for elimination of oocytes with certain DSB repair defects but does not appear to be a checkpoint protein per se, we hypothesized that it might have a role in regulating recombination partner choice. Specifically, if SYCP3 promotes DSB repair via IH recombination and/or functions as a component of the BSCR, then deleting Sycp3 would permit IS recombination, allowing DSB repair in the context of IH repair deficiency (e.g., Dmc1− or Trip13Gt). This hypothesis can be tested by attempting to override the Sycp3−/− rescue of an IH recombination mutant by disabling IS recombination repair.

In S. cerevisiae, IH recombination is driven by Dmc1 in concert with Rad51, but Rad51-driven IS recombination can occur efficiently in the absence of the BSCR and Dmc1 (see Discussion for elaboration). Intersister recombination is normally repressed in meiotic cells, presumably by downregulation of Rad51. Optimal Rad51 activity in yeast meiosis is dependent upon interaction with Rad54 to enhance strand invasion of a Rad51 presynaptic filament (Raschle et al. 2004; Heyer et al. 2006; Busygina et al. 2008; Niu et al. 2009). Rad54 in yeast is required to stimulate IS recombination. It can rescue dmc1 mutations under certain circumstances, particularly when axial element (AE) structure is disrupted (Arbel et al. 1999; Bishop et al. 1999). On the basis of analogy to yeast, we reasoned that IS recombination in mice might be suppressed by Rad54 deletion, which alone does not ablate meiosis in either sex (for oocytes, see Figure 1L) (Essers et al. 1997). We therefore constructed triple mutants (Dmc1−/− Sycp3−/− Rad54−/−) and examined the effects on oocyte survival. Whereas Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− and Sycp3−/− Rad54−/− oocytes can escape the neonatal DNA damage checkpoint (Figures 1, J and M; unlike Dmc1−/− and Dmc1−/− Rad54−/− animals, Figure 1, I and N; also Figure 2), the triply mutant ovaries were devoid of oocytes (Figure 1O; Figure 2), demonstrating that rescue of Dmc1 mutants by SYCP3 deficiency requires RAD54. Interestingly, Rad54−/− single mutants had significantly fewer total oocytes (∼25% less) than WT, attributable to ∼60% fewer primordial follicles (Figure 2). Given that RAD54 deficiency causes abnormal persistence of RAD51 foci in pachytene spermatocytes despite apparently normal fertility in these mice (Wesoly et al. 2006), this may be a reflection of RAD54 involvement in mammalian IS recombination as it is in yeast (see Discussion). Overall, these experiments suggest that activation of IS recombination rescues Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− oocytes, and that SYCP3 functions either to inhibit homology-directed IS repair or to promote IH repair at the expense of IS repair. It also raises the possibility that IS recombination may occur in WT oocytes and that loss of IS recombination may have some consequence. These interpretations imply that the escape of Sycp3−/− Rad54−/− oocytes from the DNA damage checkpoint occurs either by IH repair entirely (presumably DMC1 mediated) or a combination of IS and IH repair conducted by DMC1. In any case, the 60% reduction of primordial oocytes in these mutants compared to Sycp3 single mutants highlights a role for RAD54 in meiosis, at least in certain non-WT conditions.

SYCP3 is just one component of SC axial/lateral elements, so it is conceivable that the rescue effects with Sycp3−/− may reflect a general role for the SC in partner choice/BSCR function. Supportive of this possibility is that although axial elements form on pachytene chromosomes of SYCP3-deficient oocytes, they are abnormal and have discontinuities in the axis structure (Kouznetsova et al. 2005). If the axial element itself is governing partner choice, this would predict that deletion of other axial element components would have similar effects. Sycp3 deletion prevents SYCP2 loading onto meiotic chromosomes, and conversely, the coiled-coil domain of SYCP2 is required for loading of SYCP3 onto axial elements (Yang et al. 2006). Thus, we predicted that deletion of Sycp2 would also render oocytes to be nondependent on IH recombination for DSB repair. Consistent with this, we found that ovaries from Sycp2−/− Trip13Gt/Gt females exhibited substantial numbers of surviving oocytes, unlike Trip13Gt single mutants (Figure 1P; Figure 2), but like Sycp3−/− Trip13Gt/Gt.

Discussion

There is now molecular and genetic evidence from multiple systems that although IS recombination occurs during normal meiosis, (Schwacha and Kleckner 1994; Cromie et al. 2006) and can be relatively frequent at least at hemizygous loci (Goldfarb and Lichten 2010), it is attenuated by mechanisms that enable sufficient IH recombination for disjunction of chromosomes during the reductional division. Since IS recombination is decreased even in the absence of a homologous chromosome (Callender and Hollingsworth 2010), it appears that the IH preference is mainly or partly due to inhibition of IS interactions. In S. pombe, however, an organism lacking SC and which has a higher IS:IH recombination ratio, it is possible that IH recombination is stimulated to enable a sufficient number of crossovers (Latypov et al. 2010).

Little is known about the incidence of IS recombination in mammalian meiosis. Sister chromatid exchange (SCE) has been observed in hamster and mouse spermatocytes (Kanda and Kato 1980; Allen and Gwaltney 1984), albeit rarely and with a preference for the sex chromosomes (Allen and Latt 1976). Aside from the small pseudoautosomal region (PAR) that synapses between the X and Y, it is presumed that repair of the remaining DSBs requires IS recombination. However, IS “crossovers” that result in SCEs are estimated to constitute only ∼17–25% of all IS recombination events in yeast (Goldfarb and Lichten 2010), suggesting that most IS events will be undetectable by the classical cytological method to visualize SCEs (typically involving differential labeling of chromatids by BrdU). Another implication that IS recombination is rare in normal mammalian meiosis can be inferred by comparison to Dmc1-deficient fission yeast, which have normal spore viability but decreased crossing over (Fukushima et al. 2000). Dmc1−/− mice, however, undergo complete pachytene arrest and death of meiocytes (Pittman et al. 1998) due to the DSB damage checkpoint (Di Giacomo et al. 2005). It is possible that the DSB repair in dmc1 fission yeast is due to eventual Rad51-mediated IS + IH recombination (see below), whereas IS repair in mutant mice is infrequent despite RAD51 focus formation, with the possible exception of the asynapsed regions of the X and Y chromosomes. Notably, if indeed XY DSB repair is essential for male fertility, it must not be absolutely RAD54 dependent (Rad54−/− males are fertile). It is possible that DMC1 repairs these DSBs in Rad54 mutants, similar to the ability of S. cerevisiae Dmc1 to conduct intersister repair of DSBs in haploid meiotic cells under certain circumstances (Callender and Hollingsworth 2010).

Intersister recombination, which is efficient in mitotically growing cells, is driven by Rad51 and stimulated by Rad54, a member of the SWI/SNF class of translocases. Rad54 enhances strand invasion of a Rad51 presynaptic filament (Raschle et al. 2004; Heyer et al. 2006; Sung and Klein 2006). Although Rad51 supports efficient Dmc1-mediated IH recombination in yeast meiosis, the independent activity of Rad51 is inhibited by at least two mechanisms that block Rad54/Rad51 complex formation or synergy: (1) phosphorylation of Rad54 by Mek1 and (2) the action of Hed1 (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2006; Busygina et al. 2008; Niu et al. 2009). Deletion of BSCR proteins such as Hop1 or Red1 prevents Mek1 activation, thus releasing Rad51 inhibition and allowing IS repair to a degree that can rescue dmc1 mutant yeast (Sheridan and Bishop 2006; Niu et al. 2007). Importantly, not only do mammals have orthologs of these key recombination proteins (DMC1, RAD51, and RAD54), but also the damage signaling molecules involved in determining IH bias, including the sensor kinases (ATM/ATR) and the Hop1 mediator (HORMAD1 and/or HORMAD2) (Wojtasz et al. 2009).

In the absence of myriad tools and biological advantages in yeast that permit precise analysis of meiotic recombination events, such as the ability to visualize meiotic recombination intermediates molecularly, we must rely on informed interpretation of phenotypes we observed here. We believe the data best support a model in which the rescue of IH recombination-deficient oocytes by Sycp3 or Sycp2 deletion is attributable to altered recombination partner choice. Specifically, we hypothesize that SC axial elements facilitate IH recombination and inhibit IS recombination, possibly as part of the same mechanism.

The following experimental results support this hypothesis. First, rescue of Dmc1−/− and Trip13Gt/Gt oocytes by Sycp3 deletion does not appear to be a result of checkpoint ablation, since other DSB-repair defective mutants (Rec8 and Atm) were not rescued by SYCP3 deficiency. This, in conjunction with the observation of reduced levels of DSB markers in Dmc1−/− Sycp3−/− vs. Dmc1−/− surviving oocytes, and that Scyp3 single mutants appear to have an intact DSB repair checkpoint, suggests that DSBs were repaired via an alternative pathway in the double mutants. Second, the alternative pathway is not NHEJ exclusively because Prkdc−/− Sycp3−/− contained ample follicles at birth. It also does not appear to be DMC1-independent IH recombination; otherwise, we might expect restored fertility and synapsis in Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− oocytes. Furthermore, Sycp3 single mutants have reduced levels of crossing over (chiasmata) even in the presence of DMC1 (Wang and Hoog 2006), arguing against stimulation of such a pathway. Nevertheless, in consideration of yeast data, we do not rule out the possibility that RAD51 or RAD51 paralogs, in conjunction with RAD54, conduct some degree of interhomolog noncrossover recombination in Dmc1−/− Sycp3−/− oocytes, which is insufficient to cause synapsis and crossovers (Bishop et al. 1999). Third, deletion of Rad54, which is critical for IS recombination in S. cerevisiae, prevented rescue of Sycp3−/− Dmc1−/− oocytes. Importantly, the in vitro functions and activities of RAD54 are highly conserved (Mazin et al. 2010). Both human and mouse orthologs have branch migration activity that is promoted by Rad51 (Bugreev et al. 2006; Rossi and Mazin 2008), and they stimulate the Mus81-Eme1/Mms4 endonuclease that resolves Holliday junctions (Mazina and Mazin 2008; Matulova et al. 2009). RAD54 is also important for repair of induced DNA damage by IS repair in mouse cells (Mills et al. 2004). Interestingly, we observed a modest (∼2-fold) decrease in the primordial oocyte pool in Rad54 mutants, raising the possibility that IS recombination plays a significant role in normal oocytes. Finally, that Sycp2 deletion also rescued Trip13Gt/Gt oocytes supports the notion that the SC axial element structure itself, rather than any specific components, drives the IH preference for homologous recombination-mediated DSB repair.

Whether the same putative partner choice phenomena apply to male meiosis remains an open question. Indeed, we evaluated males of all the genotypes described for females in this study. However, analyses of spermatocytes are confounded by the fact that the timing of meiotic arrest in mutants is the same regardless of whether the defect is asynapsis (e.g., Spo11−), DSB repair (e.g., Trip13Gt), or both (e.g., Dmc1−) (Barchi et al. 2005; Li and Schimenti 2007). This complicates assessment of SYCP3’s role as a checkpoint protein vs. a recombination choice factor, since Sycp3 mutants themselves undergo zygotene/pachytene arrest with failed synapsis. For example, if SYCP3 were to have DSB repair checkpoint function exclusively, then its deletion might be expected to allow progression of Trip13Gt/Gt spermatocytes through meiosis. However, histological and immunocytological analysis of doubly mutant spermatocyte chromosomes confirmed expectations that Sycp3 is epistatic to Trip13 (Figure S1, a–d) (Yuan et al. 2000). That is, the double mutants arrested in a state resembling Sycp3 single mutants, displaying extensive asynapsis marked by γH2AX, which is indicative of meiotic silencing of unsynapsed chromatin (MSUC), which in turn disrupts XY silencing (Turner et al. 2005). Neither occurs in Trip13Gt/Gt spermatocytes (Figure S1c) (Li and Schimenti 2007). Similarly, Sycp3 deletion did not ameliorate spermatogenic arrest or the meiotic chromosomal defects in spermatocytes deficient for Dmc1 or Rec8 (Figure S2, a and b); in fact, it appeared to disrupt asynaptic homolog pairing that occurs in Rec8 mutants (Figure S2b) (Bannister et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2005).

Despite the genetic data supporting a role for SYCP3 in recombination partner choice, we caution that other explanations are conceivable. We concluded that SYCP3 is not strictly a DNA damage checkpoint protein because its deletion failed to rescue Rec8−/− or Atm−/− oocytes, both of which undergo SPO11-dependent checkpoint elimination. Additionally, a DNA damage checkpoint appears to remain intact in Sycp3 single mutants. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that SYCP3 and/or SYCP2 are checkpoint proteins solely responsible for detecting lesions left by certain mutants including Trip13 and Dmc1. Still, the case of Rec8 mutants may be consonant with a role of SYCP3 in blocking IS recombination. Since IH recombination is defective in Rec8−/− oocytes, and cohesins are required for efficient repair of DSBs by sister chromatid recombination (Sjogren and Nasmyth 2001; Cortes-Ledesma and Aguilera 2006; Sjogren and Strom 2010), this could explain the lack of rescue by Sycp3 deletion. The situation with Atm mutants is more difficult to interpret. Their chromosomal defects—including chromosome fragmentation and chromosome axis disruption—may be of a nature that cannot be repaired by IS recombination (in Sycp3 mutants) to a degree that allows bypass of damage and spindle checkpoints (Xu et al. 1996; Barchi et al. 2008). Alternatively, ATM, which is a key DNA damage response factor in somatic cells and leptotene spermatocytes (Bellani et al. 2005), may be required for triggering efficient repair by both IH and IS recombination.

Another caveat is that the reduced rate of DSB repair in Sycp3−/− oocytes (Wang and Hoog 2006) is not easily reconciled with our hypothesis that the axial element (AE) promotes IH bias, at least in part by inhibiting IS repair. We suggest two possible explanations. One is that certain proteins involved in IS recombination are limiting in oocytes (for example, RAD51), such that, whereas IS interactions are favored, processing of recombination intermediates is hampered. Another possibility is that the AE not only inhibits IS recombination, but also enhances IH recombination to a greater relative degree. In this scenario, the decreased efficiency of IH recombination slows overall DSB repair, increasing the ratio of IS:IH recombination, leading to the observed reduction in crossovers, elevated aneuploidy, and checkpoint-mediated elimination of many oocytes before they complete DSB repair (Wang and Hoog 2006).

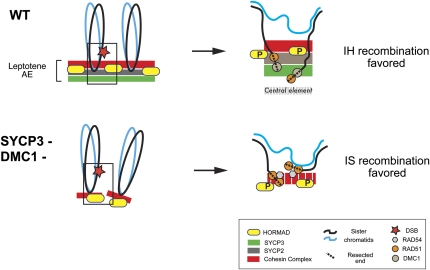

Our data show that the SC proteins SYCP2 and SYCP3 are required for the complete elimination of oocytes that are defective for repair of IH meiotic DSBs by homologous recombination, and genetic evidence suggests that SYCP3 does so by inhibiting IS recombination. Our results, considered in conjunction with data from budding yeast and mice, lead us to propose that intact axial elements, the precursors of the lateral element of the mature SC, constitute the critical organizer of recombination pathway and partner bias in mammalian meiosis. As diagrammed in Figure 4, the basic tenet of this model is that RAD51/DMC1 nucleoprotein filaments that form at resected ends of DSBs are oriented by, or bound to AE components (possibly SYCP2 and/or SYCP3) in such a way as to inhibit interaction with the sister chromatid, while spacially favoring homologous chromosome interactions.

Figure 4 .

Model for role of axial element in promoting interhomolog recombination bias. (Top) DSBs occur during leptonema. In yeast it is thought that DSBs are dependent upon AE formation, in part because mutations of AE proteins such as Red1 and Hop1 decrease DSB levels (Zickler and Kleckner 1999). However, the temporal relationship is not clear in mice because RAD51/DMC1 foci (surrogates of DSBs) appear concurrent to and colocalize with AE components. Nevertheless, numerous immunocytological studies show that the DSB ends become localized to the AE cores. RAD51 and DMC1 foci in normal meiosis also colocalize to nascent AEs and HORMADs in leptonema (Barlow et al. 1997; Wojtasz et al. 2009) and actually directly interact with SYCP3 (Tarsounas et al. 1999). (Bottom) Localization of SYCP2 is dependent upon SYCP3, so as indicated, loss of SYCP3 results in aberrant pseudoaxial elements, or cores, consisting only of cohesin proteins such as REC8, SMC1β, and STAG3 (Pelttari et al. 2001; Fukuda et al. 2010). In our model, the disrupted AE structure caused by SYCP2/SYCP3 absence, which also causes discontinuities in the cohesin complex (dashed red line) allows the RAD51-bound DSB ends (depicted here in Dmc1 mutants) to have unimpeded access to the sister and will recombine in a RAD54-dependent manner. See text for more details.

Yeast-based models to explain IH bias have in common either a physical orientation of DSB ends toward the SC central element (and homologous chromosome), highlighting specific molecules such as the Rec8 cohesin (Kim et al. 2010) or Hed1 and Mek1 (Sheridan and Bishop 2006) or emphasizing local chromatin modifications that have a similar consequence (Goldfarb and Lichten 2010). It is not clear whether the mechanisms of homolog bias will be the same in mammals, given our limited state of knowledge. Important similarities are that essential components of the IH bias/barrier to sister chromatid recombination in yeast are axial element proteins (Red1, Mek1, and Hop1), as are SYCP3 and SYCP2 in mice (our data), as well as the cohesin Rec8. Mice have two Hop1 orthologs, HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, that become colocalized to nascent AEs (“cores”) during leptonema and are removed upon synapsis, consistent with a role conserved with Hop1 and/or Red1 (Wojtasz et al. 2009; Fukuda et al. 2010). Additionally, Hormad1 mutants have decreased DSB levels as do hop1 yeast (Shin et al. 2010), but it is not known whether Hormad1 has a role in partner choice. On the other hand, there are some differences between the organisms. Notably, SYCP3 is not required for DSB formation unlike yeast AE proteins, and REC8 is not required for AE formation in mice as it is in S. cerevisiae (Bannister et al. 2004). These differences may have to do with the higher number of axis proteins present in mammalian chromosomes vs. yeast, especially cohesins (Revenkova et al. 2010). Furthermore, Rec8 mutation is so severe (Rec8−/− oocyte elimination is SPO11 dependent) that it cannot be determined whether it influences initial partner choice as it does in yeast (Kim et al. 2010). However, it is possible that as in the Kim et al. (2010) model for yeast, SYCP3 may function in part to locally disrupt the bias toward IS recombination that REC8 otherwise promotes early after DSB formation. Alternatively, our results may be consistent with the Kim et al. (2010) finding that in later stages of recombination, yeast Rec8 acts to enforce IH bias. Kouznetsova et al. (2005) observed that the lateral axis SC structure in Sycp3−/− oocytes has discontinuities in staining for cohesins including STAG3 and REC8. These local disruptions of the cohesin complex may compromise IH bias. A final difference with yeast, in which Tel1 and/or Mec1 phosphorylate Hop1 in response to Spo11 DSBs (Carballo et al. 2008), is that mouse Hop1 (HORMAD1) appears to act upstream of ATM and ATR (Shin et al. 2010). HORMAD1 is indeed phosphorylated, but the kinase remains unknown, as does the potential ortholog of the downstream effector Mek1.

HORMAD1 coimmunoprecipitates with SYCP3, SYCP2, and AE-bound cohesins, but it does not require SYCP3 to colocalize to aberrant core-like structures that are defective due to lack of SYCP3 (Fukuda et al. 2010). Therefore, we conclude that HORMAD1 loss is not sufficient for the phenomena (rescue of Dmc1 or Trip13 mutants by Sycp3 deletion) we observe here. Conversely, SYCP3 does not require HORMAD1 to integrate into AEs (Shin et al. 2010). Recently, evidence has been presented that HORMAD1 depletion depresses SPO11-induced DSBs and is involved in the oocyte checkpoint that detects asynapsis (Daniel et al. 2011). It remains to be seen whether all the AE components (other than REC8, the deletion of which causes early oocyte death) are important for maintaining IH bias. We favor the idea that the overall AE structure is critical, and that loss of certain individual components may phenocopy the effects we have observed here.

The control of meiotic recombination and partner choice is of high relevance to human health. This is indicated by the phenotype of Sycp3−/− mice. They manage to conduct DSB repair but, as a result of decreased crossing over, undergo oocyte loss and produce aneuploid gametes. SYCP3 mutations in human females have been associated with recurrent pregnancy loss, suggestive of fetal chromosome abnormalities (Bolor et al. 2009). Nevertheless, obtaining proof that axial elements control recombination partner choice awaits the development of effective methodologies for assaying sister chromatid recombination in meiocytes. This is complicated by the fact that oocytes undergo meiosis in utero. Such analyses may be made possible by developments that allow cytological analyses of chromosome exchanges, molecular analysis of individual DSB repair events, or bulk physical studies of recombination intermediates that occur at strong “hotspots.”

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Zanders and Eric Alani for advice on the manuscript and Michael Lichten, Scott Keeney, and Paula Cohen for helpful discussions. We are indebted to P. Jeremy Wang for providing Sycp2 mice, Christer Hoog for Sycp3 mice (via Paula Cohen), and Roland Kanaar for Rad54 mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM45415 to J.C.S.

Literature Cited

- Allen J. W., Latt S. A., 1976. In vivo BrdU-33258 Hoechst analysis of DNA replication kinetics and sister chromatid exchange formation in mouse somatic and meiotic cells. Chromosoma 58: 325–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. W., Gwaltney C. W., 1984. Sister chromatid exchanges in mammalian meiotic chromosomes. Basic Life Sci 29 Pt B: 629–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allers T., Lichten M., 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106: 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L. K., Reeves A., Webb L. M., Ashley T., 1999. Distribution of crossing over on mouse synaptonemal complexes using immunofluorescent localization of MLH1 protein. Genetics 151: 1569–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbel A., Zenvirth D., Simchen G., 1999. Sister chromatid-based DNA repair is mediated by RAD54, not by DMC1 or TID1. EMBO J. 18: 2648–2658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister L. A., Reinholdt L. G., Munroe R. J., Schimenti J. C., 2004. Positional cloning and characterization of mouse mei8, a disrupted allelle of the meiotic cohesin Rec8. Genesis 40: 184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi M., Mahadevaiah S., Di Giacomo M., Baudat F., de Rooij D. G., et al. , 2005. Surveillance of different recombination defects in mouse spermatocytes yields distinct responses despite elimination at an identical developmental stage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 7203–7215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi M., Roig I., Di Giacomo M., de Rooij D. G., Keeney S., et al. , 2008. ATM promotes the obligate XY crossover and both crossover control and chromosome axis integrity on autosomes. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow A., Benson F., West S., Hultén M., 1997. Distribution of the Rad51 recombinase in human and mouse spermatocytes. EMBO J. 16: 5207–5215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat F., Manova K., Yuen J. P., Jasin M., Keeney S., 2000. Chromosome synapsis defects and sexually dimorphic meiotic progression in mice lacking Spo11. Mol. Cell 6: 989–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellani M. A., Romanienko P. J., Cairatti D. A., Camerini-Otero R. D., 2005. SPO11 is required for sex-body formation, and Spo11 heterozygosity rescues the prophase arrest of Atm−/− spermatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 118: 3233–3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N., Dernburg A. F., 2005. A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 310: 1683–1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. K., Nikolski Y., Oshiro J., Chon J., Shinohara M., et al. , 1999. High copy number suppression of the meiotic arrest caused by a dmc1 mutation: REC114 imposes an early recombination block and RAD54 promotes a DMC1-independent DSB repair pathway. Genes Cells 4: 425–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolor H., Mori T., Nishiyama S., Ito Y., Hosoba E., et al. , 2009. Mutations of the SYCP3 gene in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84: 14–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner G. V., Kleckner N., Hunter N., 2004. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117: 29–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugreev D. V., Mazina O. M., Mazin A. V., 2006. Rad54 protein promotes branch migration of Holliday junctions. Nature 442: 590–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne P. S., Mahadevaiah S. K., Turner J. M., 2007. The management of DNA double-strand breaks in mitotic G2, and in mammalian meiosis viewed from a mitotic G2 perspective. Bioessays 29: 974–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busygina V., Sehorn M. G., Shi I. Y., Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S., et al. , 2008. Hed1 regulates Rad51-mediated recombination via a novel mechanism. Genes Dev. 22: 786–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callender T. L., Hollingsworth N. M., 2010. Mek1 suppression of meiotic double-strand break repair is specific to sister chromatids, chromosome autonomous and independent of Rec8 cohesin complexes. Genetics 185: 771–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo J., Johnson A., Sedgwick S., Cha R., 2008. Phosphorylation of the axial element protein Hop1 by Mec1/Tel1 ensures meiotic interhomolog recombination. Cell 132: 758–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang T., Duncan F. E., Schindler K., Schultz R. M., Lampson M. A., 2010. Evidence that weakened centromere cohesion is a leading cause of age-related aneuploidy in oocytes. Curr. Biol. 20: 1522–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Ledesma F., Aguilera A., 2006. Double-strand breaks arising by replication through a nick are repaired by cohesin-dependent sister-chromatid exchange. EMBO Rep. 7: 919–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie G. A., Smith G. R., 2007. Branching out: meiotic recombination and its regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 17: 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie G. A., Hyppa R. W., Taylor A. F., Zakharyevich K., Hunter N., et al. , 2006. Single Holliday junctions are intermediates of meiotic recombination. Cell 127: 1167–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel K., Lange J., Hached K., Fu J., Anastassiadis K., et al. , 2011. Meiotic homologue alignment and its quality surveillance are controlled by mouse HORMAD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13: 599–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veaux L. C., Hoagland N. A., Smith G. R., 1992. Seventeen complementation groups of mutations decreasing meiotic recombination in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 130: 251–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giacomo M., Barchi M., Baudat F., Edelmann W., Keeney S., et al. , 2005. Distinct DNA-damage-dependent and -independent responses drive the loss of oocytes in recombination-defective mouse mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 737–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson A., Wang Y., Daugherty C. J., Morton C. C., Zhou F., et al. , 1996. Pleiotropic defects in ataxia-telangiectasia protein-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 13084–13089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers J., Hendriks R. W., Swagemakers S. M., Troelstra C., de Wit J., et al. , 1997. Disruption of mouse Rad54 reduces ionizing radiation resistance and homologous recombination. Cell 89: 195–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T., Daniel K., Wojtasz L., Toth A., Hoog C., 2010. A novel mammalian HORMA domain-containing protein, HORMAD1, preferentially associates with unsynapsed meiotic chromosomes. Exp. Cell Res. 316: 158–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K., Tanaka Y., Nabeshima K., Yoneki T., Tougan T., et al. , 2000. Dmc1 of Schizosaccharomyces pombe plays a role in meiotic recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 2709–2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getun I. V., Wu Z. K., Khalil A. M., Bois P. R., 2010. Nucleosome occupancy landscape and dynamics at mouse recombination hotspots. EMBO Rep. 11: 555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial A., Schupbach T., 1999. Activation of a meiotic checkpoint regulates translation of Gurken during Drosophila oogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 1: 354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb T., Lichten M., 2010. Frequent and efficient use of the sister chromatid for DNA double-strand break repair during budding yeast meiosis. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon H., Baudat F., Grey C., Liskay R. M., de Massy B., 2005. Crossover and noncrossover pathways in mouse meiosis. Mol. Cell 20: 563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Hall H., Hunt P., 2007. The origin of human aneuploidy: where we have been, where we are going. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 Spec No. 2: R203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer W. D., Li X., Rolfsmeier M., Zhang X. P., 2006. Rad54: The Swiss army knife of homologous recombination? Nucleic Acids Res. 34: 4115–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges C. A., Revenkova E., Jessberger R., Hassold T. J., Hunt P. A., 2005. SMC1beta-deficient female mice provide evidence that cohesins are a missing link in age-related nondisjunction. Nat. Genet. 37: 1351–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N., Kleckner N., 2001. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-Holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell 106: 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. A., Fink G. R., 1985. Meiotic recombination between duplicated genetic elements in Saccharomyces cerevesiae. Genetics 109: 303–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk L. C., Hartwell L. H., 1992. Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 132: 387–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda N., Kato H., 1980. Analysis of crossing over in mouse meiotic cells by BrdU labelling technique. Chromosoma 78: 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. P., Weiner B. M., Zhang L., Jordan A., Dekker J., et al. , 2010. Sister cohesion and structural axis components mediate homolog bias of meiotic recombination. Cell 143: 924–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler K. E., Cherry J. P., Lynn A., Hunt P. A., Hassold T. J., 2002. Genetic control of mammalian meiotic recombination. I. Variation in exchange frequencies among males from inbred mouse strains. Genetics 162: 297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouznetsova A., Novak I., Jessberger R., Hoog C., 2005. SYCP2 and SYCP3 are required for cohesin core integrity at diplotene but not for centromere cohesion at the first meiotic division. J. Cell Sci. 118: 2271–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao J. P., Hunter N., 2010. Trying to avoid your sister. PLoS Biol. 8: e1000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latypov V., Rothenberg M., Lorenz A., Octobre G., Csutak O., et al. , 2010. Roles of Hop1 and Mek1 in meiotic chromosome pairing and recombination partner choice in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30: 1570–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. C., Schimenti J. C., 2007. Mouse pachytene checkpoint 2 (Trip13) is required for completing meiotic recombination but not synapsis. PLoS Genet. 3: e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby B. J., Reinholdt L. G., Schimenti J. C., 2003. Positional cloning and characterization of Mei1, a vertebrate-specific gene required for normal meiotic chromosome synapsis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 15706–15711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. J., Chapo J., Roig I., Abrams J. M., 2010. Meiotic recombination provokes functional activation of the p53 regulatory network. Science 328: 1278–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevaiah S. K., Bourc’his D., de Rooij D. G., Bestor T. H., Turner J. M., et al. , 2008. Extensive meiotic asynapsis in mice antagonises meiotic silencing of unsynapsed chromatin and consequently disrupts meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. J. Cell Biol. 182: 263–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulova P., Marini V., Burgess R. C., Sisakova A., Kwon Y., et al. , 2009. Cooperativity of Mus81.Mms4 with Rad54 in the resolution of recombination and replication intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 7733–7745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Mazin A. V., Mazina O. M., Bugreev D. V., Rossi M. J., 2010. Rad54, the motor of homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst.) 9: 286–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazina O. M., Mazin A. V., 2008. Human Rad54 protein stimulates human Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 18249–18254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen R. L., Offenberg H. H., Dietrich A. J., Riesewijk A., van Iersel M., et al. , 1992. A coiled-coil related protein specific for synapsed regions of meiotic prophase chromosomes. EMBO J. 11: 5091–5100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K. D., Ferguson D. O., Essers J., Eckersdorff M., Kanaar R., et al. , 2004. Rad54 and DNA Ligase IV cooperate to maintain mammalian chromatid stability. Genes Dev. 18: 1283–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M., Britt K. L., Wreford N. G., Ebling F. J., Kerr J. B., 2004. Methods for quantifying follicular numbers within the mouse ovary. Reproduction 127: 569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H., Li X., Job E., Park C., Moazed D., et al. , 2007. Mek1 kinase is regulated to suppress double-strand break repair between sister chromatids during budding yeast meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 5456–5467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H., Wan L., Baumgartner B., Schaefer D., Loidl J., et al. , 2005. Partner choice during meiosis is regulated by Hop1-promoted dimerization of Mek1. Mol. Biol. Cell 16: 5804–5818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H., Wan L., Busygina V., Kwon Y., Allen J. A., et al. , 2009. Regulation of meiotic recombination via Mek1-mediated Rad54 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 36: 393–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvanov E. D., Petkov P. M., Paigen K., 2010. Prdm9 controls activation of mammalian recombination hotspots. Science 327: 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelttari J., Hoja M. R., Yuan L., Liu J. G., Brundell E., et al. , 2001. A meiotic chromosomal core consisting of cohesin complex proteins recruits DNA recombination proteins and promotes synapsis in the absence of an axial element in mammalian meiotic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 5667–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman D., Cobb J., Schimenti K., Wilson L., Cooper D., et al. , 1998. Meiotic prophase arrest with failure of chromosome pairing and synapsis in mice deficient for Dmc1, a germline-specific RecA homolog. Mol. Cell 1: 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plug A. W., Xu J., Reddy G., Golub E. I., Ashley T., 1996. Presynaptic association of Rad51 protein with selected sites in meiotic chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 5920–5924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschle M., Van Komen S., Chi P., Ellenberger T., Sung P., 2004. Multiple interactions with the Rad51 recombinase govern the homologous recombination function of Rad54. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 51973–51980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholdt L., Ashley T., Schimenti J., Shima N., 2004. Forward genetic screens for meiotic and mitotic recombination-defective mutants in mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 262: 87–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholdt L. G., Schimenti J. C., 2005. Mei1 is epistatic to Dmc1 during mouse meiosis. Chromosoma 114: 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenkova E., Adelfalk C., Jessberger R., 2010. Cohensin in oocytes: Tough enough for mammalian meiosis? Genes 1: 495–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder G. S., 1997. Meiotic chromosomes: it takes two to tango. Genes Dev. 11: 2600–2621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder G. S., Bailis J. M., 2000. The pachytene checkpoint. Trends Genet. 16: 395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig I., Dowdle J. A., Toth A., de Rooij D. G., Jasin M., et al. , 2010. Mouse TRIP13/PCH2 is required for recombination and normal higher-order chromosome structure during meiosis. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanienko P. J., Camerini-Otero R. D., 2000. The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol. Cell 6: 975–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. J., Mazin A. V., 2008. Rad51 protein stimulates the branch migration activity of Rad54 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 24698–24706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H., Polikiewicz G., Mahadevaiah S. K., Prosser H., Mitchell M., et al. , 2010. Evidence that meiotic sex chromosome inactivation is essential for male fertility. Curr. Biol. 20: 2117–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A., Kleckner N., 1994. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76: 51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A., Kleckner N., 1997. Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell 90: 1123–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan S., Bishop D. K., 2006. Red-Hed regulation: recombinase Rad51, though capable of playing the leading role, may be relegated to supporting Dmc1 in budding yeast meiosis. Genes Dev. 20: 1685–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y. H., Choi Y., Erdin S. U., Yatsenko S. A., Kloc M., et al. , 2010. Hormad1 mutation disrupts synaptonemal complex formation, recombination, and chromosome segregation in mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren C., Nasmyth K., 2001. Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 11: 991–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren C., Strom L., 2010. S-phase and DNA damage activated establishment of sister chromatid cohesion–importance for DNA repair. Exp. Cell Res. 316: 1445–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark J. M., Jasin M., 2003. Extensive loss of heterozygosity is suppressed during homologous repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 733–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P., Klein H., 2006. Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediators and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7: 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana-Konwalski K., Godwin J., van der Weyden L., Champion L., Kudo N. R., et al. , 2010. REC8-containing cohesin maintains bivalents without turnover during the growing phase of mouse oocytes. Genes Dev. 24: 2505–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsounas M., Morita T., Pearlman R. E., Moens P. B., 1999. RAD51 and DMC1 form mixed complexes associated with mouse meiotic chromosome cores and synaptonemal complexes. J. Cell Biol. 147: 207–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H., Roeder G. S., 2006. Budding yeast Hed1 down-regulates the mitotic recombination machinery when meiotic recombination is impaired. Genes Dev. 20: 1766–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. M., Mahadevaiah S. K., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Nussenzweig A., Xu X., et al. , 2005. Silencing of unsynapsed meiotic chromosomes in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 37: 41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Hoog C., 2006. Structural damage to meiotic chromosomes impairs DNA recombination and checkpoint control in mammalian oocytes. J. Cell Biol. 173: 485–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. O., Reinholdt L. G., Motley W. W., Niswander L. M., Deacon D. C., et al. , 2007. Mutation in mouse Hei10, an e3 ubiquitin ligase, disrupts meiotic crossing over. PLoS Genet. 3: e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrin E., Peters J. M., 2006. Cohesin and DNA damage repair. Exp. Cell Res. 312: 2687–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesoly J., Agarwal S., Sigurdsson S., Bussen W., Van Komen S., et al. , 2006. Differential contributions of mammalian Rad54 paralogs to recombination, DNA damage repair, and meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 976–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasz L., Daniel K., Roig I., Bolcun-Filas E., Xu H., et al. , 2009. Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Y., Burgess S. M., 2006. Two distinct surveillance mechanisms monitor meiotic chromosome metabolism in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 16: 2473–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. K., Getun I. V., Bois P. R., 2010. Anatomy of mouse recombination hot spots. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 2346–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Beasley M. D., Warren W. D., van der Horst G. T., McKay M. J., 2005. Absence of mouse REC8 cohesin promotes synapsis of sister chromatids in meiosis. Dev. Cell 8: 949–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Weiner B. M., Kleckner N., 1997. Meiotic cells monitor the status of the interhomolog recombination complex. Genes Dev. 11: 106–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Ashley T., Brainerd E. E., Bronson R. T., Meyn M. S., et al. , 1996. Targeted disruption of Atm leads to growth retardation, chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, immune defects, and thymic lymphoma. Genes Dev. 10: 2411–2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., De La Fuente R., Leu N. A., Baumann C., McLaughlin K. J., et al. , 2006. Mouse SYCP2 is required for synaptonemal complex assembly and chromosomal synapsis during male meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 173: 497–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Kondoh G., Matsuda Y., Habu T., Nishimune Y., et al. , 1998. The mouse RecA-like gene Dmc1 is required for homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis. Mol. Cell 1: 707–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Liu J. G., Zhao J., Brundell E., Daneholt B., et al. , 2000. The murine SCP3 gene is required for synaptonemal complex assembly, chromosome synapsis, and male fertility. Mol. Cell 5: 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler D., Kleckner N., 1999. Meiotic chromosomes: integrating structure and function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33: 603–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]