Abstract

Patient-centered home care is a new model of assistance, which may be integrated with more traditional hospital-centered care especially in selected groups of informed and trained patients. Patient-centered care is based on patients’ needs rather than on prognosis, and takes into account the emotional and psychosocial aspects of the disease. This model may be applied to elderly patients, who present comorbid diseases, but it also fits with the needs of younger fit patients. A specialized multidisciplinary team coordinated by experienced medical oncologists and including pharmacists, psychologists, nurses, and social assistance providers should carry out home care. Other professional figures may be required depending on patients’ needs. Every effort should be made to achieve optimal coordination between the health professionals and the reference hospital and to employ shared evidence-based guidelines, which in turn guarantee safety and efficacy. Comprehensive care has to be easily accessible and requires a high level of education and knowledge of the disease for both the patients and their caregivers. Patient-centered home care represents an important tool to improve quality of life and help cancer patients while also being cost effective.

Keywords: cancer, home care, chemotherapy, biologic agents

Introduction

In the Western world cancer is the most common cause of premature death and disability, with very important social and economic consequences that at present are not precisely measured, and therefore often ignored. National health systems are faced with an increasing incidence and prevalence of cancer as the whole population lives longer.1 In practical terms, oncology organizations have to support an increasing number of patients requiring more therapeutic interventions, long lasting care, and longer follow-up time.2 Consequently, there is an increasing need for resources to manage the long-term survivors, and provide ongoing patient education and better psychosocial support. To deal with this problem, health providers need to find a more flexible model of cancer care in order to meet patient needs.

In 2005 the USA Institute of Medicine identified six major phases in the cancer care continuum: prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care.3 According to this schema, improvement of care and quality of life as well as the development of new models of care were reported as major objectives.

Quality of care

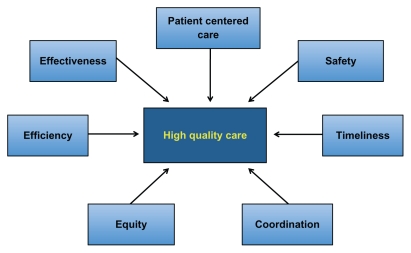

Patient-centered care is considered a pivotal aspect of high-quality health care.4 As shown in Figure 1, high-quality health care includes all of the followings aims: (a) effectiveness, i.e. the use of evidence-based medicine; (b) safety, including avoidance of preventable errors; (c) efficiency, in order to reduce waste as much as possible; (d) timeliness, in order to avoid unnecessary delays; and (e) equity, regardless of sociodemographic characteristics.4 Patient-centered care is “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values.”5 These aims may well be applied also in oncology in which patient-health provider communication and relationships are of paramount importance. Coordination of care represents another fundamental pillar of high-quality health care due to the multidisciplinary approach to cancer patients. The concept of patient-centered assistance is further strengthened by the continuously increasing personalization of antineoplastic treatments as a positive consequence of biological and medical knowledge achieved in the last decade.6 Patient-centered research has also been advocated for participation in prospectively randomized clinical trials.7

Figure 1.

Pillars of high quality of care.

The aims of patient-centered care fit very well in a cancer management home program, which represents a new model of cancer care which may be integrated with more traditional models of assistance.8 Cancer patient-centered home care (CPCHC) programs may include the active assistance of patients treated with oral or even intravenous agents, both chemotherapeutic and biologic drugs, outside of the hospital clinic. In a strict sense, home chemotherapy refers to the full home administration of treatment, even if infusion chemotherapy may be started at the hospital and continued – as often happens today – at home without supervision.

At a first glance, the CPCHC approach is obviously considered applicable to unfit or elderly patients but in reality, it may also extend to fit patients. Fit patients usually have less hospital needs and better tolerance to oncological treatments. Moreover it should be considered that emotional and psychosocial aspects play a pivotal role since cancer patients often feel more comfortable and secure being cared for at home. Many patients want to stay at home so that they will not be separated from family, friends, and familiar surroundings.

Principles of cancer patientcentered home care

CPCHC is considered as the future of primary care practice that will be part of the US health care system change into a more accessible, effective, efficient, safe, and economical sustainable system. In accordance with similar medical systems, this new model of assistance must incorporate several principles of care shown in Table 1.9,10 The guidelines of the Association of Community Cancer Centers homecare program state that “the home cancer care staff must be capable of providing appropriate and competent care for cancer patients and their families at any stage of the disease”. Therefore CPCHC must be run by a highly specialized health care team coordinated by experienced oncologists and must work in cooperation with affiliated comprehensive cancer centers and other health care providers in order to guarantee an adequate and coordinated continuum of care and an ongoing relationship between patients and physicians.

Table 1.

Principles of cancer patient-centered home care (CPCHC)

|

The progression of any cancer patient through the cancer care continuum is not straightforward and has in fact been described as a labyrinth.11 The key issues at the basis of any home anticancer treatment service are outlined in Table 2. The coordinating oncologist and the whole caregiver team have the responsibility of guiding and supporting patients therefore enabling and empowering patients to live with cancer as a chronic disease.11 Care should be directed to the whole person’s needs, which may vary from preventive to end of life or from acute to chronic care. In accomplishing these aims, the involvement of family caregivers is essential for optimal management of cancer patients in ensuring treatment adherence and persistence, continuity of care, and social support, particularly in the most critical phases such as communication of diagnosis or at the end of life.12 In many cases caregivers intervene under the pressure of sudden and extreme circumstances, without adequate education, knowledge of the disease or support from the health care system. Safety and quality of therapies and care should be met as much as possible by using shared and accepted evidence-based guidelines and the use of clinical decision support tools, accurate information, and patient information.13 In this setting, trained nurses and pharmacists play a pivotal role along with the physician, social support givers, and family. Access to oncological care should be enhanced through various systems such as open scheduling, extended contact time, and improved methods of communication. Therefore accurate coordination between all segments of this continuum of care and the patient’s community plays a pivotal role.

Table 2.

Key issues for a home anticancer treatment service

|

Measures of patient-centered care

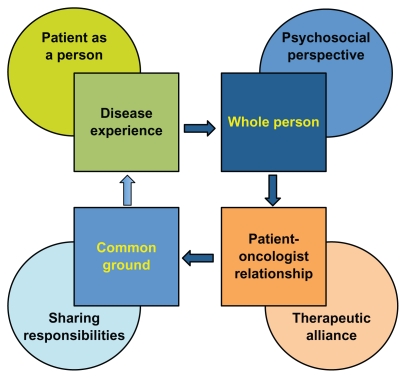

To date no widely accepted conceptual model of patient- centered care exists.14 Figure 2 shows a possible framework including four dimensions: disease experience ( patient-as-person); whole person (bio-psychosocial perspective); common ground (sharing power and responsibility); and patient–physician relationship (therapeutic alliance). Several approaches have been employed for creating instruments to measure patient-centered care. The most widely employed approaches are direct observation by the heath care provider in the form of a structured objective checklist; physician reports; and patient self-assessment through the use of questionnaires, the latter being the most precise in predicting outcomes.15

Figure 2.

Patient-centered care conceptual framework.

Clinical evidence

The issue of home therapy in oncology care is not new. In 1989 McCorkle et al carried out a randomized clinical trial to determine the effects of home nursing care versus usual office care for 166 patients with progressive lung cancer.16 Although there were no differences in pain, mood disturbance, and concerns, significant differences in symptom distress, enforced social dependency, and health perceptions were reported. These results suggested that home nursing care assists patients with forestalling distress from symptoms and maintaining their independence longer in comparison to no home nursing care.

Despite widespread attention and endorsement by health care agencies, limited research exists evaluating principles of cancer patient-centered home care or testing the effectiveness of this model in community practice. There is insufficient evidence about the effectiveness, in terms of clinical outcomes (survival, objective response), of home chemotherapy compared to hospital administration.17 More sound evidence exists on safety, although patients must be carefully selected and trained. Home delivery of anticancer agents is feasible for selected categories of patients such as those receiving oral treatments, zoledronic acid, low-intensity intravenous chemotherapy (ie, gemcitabine or vinorelbine) or biologic agents (ie, herceptin), while patients receiving intensive treatments are not suitable for home care. Table 3 shows the advantages of a home therapy care unit for both patients and health-providers.

Table 3.

Advantages of a home therapy care unit

Patients’ advantages:

|

In the last decade, the use of antineoplastic agents has increased dramatically, as the number of cancer patients has risen and developments in technology have expanded the groups suitable for treatments, especially those involving long infusions or requiring oral therapy and/or less complex chemotherapy regimens.18 In the UK and the US, the excessive burden on some chemotherapy units has led to the development of an innovative concept of care model which would allow less complex cancer treatments to be delivered at home outside of the acute hospital setting.19 For instance the Christie NHS Foundation Trust in the UK has rapidly implemented the home delivery of trastuzumab to early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer patients after the first three hospital administrations in the absence of significant side effects. All treatment is carried out under the direction of the patient’s oncologist, who retains ultimate responsibility for the patient’s care and with whom close contact is maintained at all times. Another study carried out in Ireland including 274 patients, of whom 39 were treated at home with 5-fluorouracil infusion-based chemotherapy, reported high levels of patient satisfaction (80%) with the services received at home and the level of information received.20 More than 90% of patients felt home treatment was less distressing than hospital admission. Fear of in-hospital acquired infection was reported by 50% of patients, while less than 10% reported that they missed the company of patients in a similar position.

The Health Technology Assessment Agency of Canada analyzed home cancer chemotherapy in terms of patient benefit, safety, costs, organizational issues, and delivery implications.21 Home oral and intravenous cancer treatment is feasible for some patients and can be delivered safely if individuals and their familiar caregivers are carefully selected and trained. Patient eligibility criteria include learning capability, home environment, and geographic accessibility. The latter issue raises problems since home therapy may be quite difficult in rural areas. Although improvements in patient quality of life at home have not been well documented, patient preference/satisfaction with home therapy is evident.

An efficient CPHCP must work in a strategic partnership with the reference oncology hospital. In a large study carried out in the US, 756 patients with advanced stage disease, of which 75% were oncology patients, were included in a patient-centered model including home visits and telephone calls.22 This program resulted in a reduction of hospital admissions (38%), emergency room visits (30%), and number of diagnoses of side effects, such as nausea, anemia, and dehydration. Patients’ satisfaction rate was high (92%), with an increase in the use of hospice and home care of 62% and 30%, respectively.

A randomized crossover trial was carried out at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute in Melbourne, Australia, to determine patients’ preferences and cost differences between home-based and hospital-based chemotherapy.23 Although only 20 patients were enrolled, home-based chemotherapy was the preferred option by all patients. There were no significant complications associated with administration of chemotherapy in the home and no negative reports by patients themselves.

The application of approved treatment guidelines is extremely useful in improving cancer care as shown by a report from a home care program in the US.24 A standardized approach to dehydration prevention education and management resulted in fewer patients seeking emergency aid and inpatient care for dehydration, while standardized management of outpatient diarrhea cut the number of admissions for treatment of Clostridium difficile enteritis by more than 50%. Likewise, standardized prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy dramatically decreased the practice-wide use of oral 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 inhibitors. These actions ultimately minimized irrelevant activities that steal time from the oncologist’s day. A steady decrease in the number and rate of emergency department referrals for chemotherapy patients has been recorded if patient-centered care is applied. Overall, hospital admissions for cancer patients fell by 16% between 2008 and 2009 and fell by another 10% in 2010.24

Oral therapies

In the last decade, the use of oral anticancer agents for the treatment of various types of cancer has been constantly increasing.25,26 Of all the cancer therapies under clinical development, 20%–25% are expected to be oral. Currently in the US and Europe, more than 40 oral agents have been approved for the treatment of cancer. The intravenous-to-oral switch and the development of oral anticancer therapies for long-term daily use will most likely continue to evolve. The issue of oral cancer therapy is particularly important in a model of patient-centered home care. Oral treatments de facto represent a home therapy since most patients take pills at their houses and manage their treatment directly or with their familiar caregivers.25

Economic issues

Costs and convenience of delivering cancer treatments at home versus hospital services were analyzed in a study of 82 patients who received home cancer treatment for at least 2 weeks under the coordination of a public cancer center in Lyon, France.27 The hypothetical costs of hospital stay were reconstructed for each individual receiving home care according to the type of cancer care required: chemotherapy, palliative care, and other treatments. Home cancer treatments were less costly than traditional inpatient hospital care for the palliative care and other treatment groups, while no significant cost difference was found for the chemotherapy group. However, because this study evaluated costs from the perspective of the public payer, costs borne by the individual or family were not considered. Therefore the cost effectiveness of home versus hospital cancer programs from a societal perspective, which would include costs borne by the individual and family receiving care, should also be analyzed.

The Irish experience showed that home care cut costs by two-thirds compared to hospital care.20 If savings associated with transport and increased risk of hospital acquired infection were taken into account, the study suggested that home chemotherapy would appear even more cost advantageous and provide even better economic advantage for the tax payer. In a US study, cost analysis also showed a reduction in expenses as compared to patients not enrolled in the program.22 On the other hand a Canadian study reported that home chemotherapy was less costly than inpatient treatment in a hospital, but findings were mixed when home therapy was used as a substitute for outpatient therapy.21 In the Australian experience, home-based treatment resulted in an increased cost compared with hospital-based treatment, but it was associated with several advantages such as elimination of travel, reduction in treatment-associated anxiety, and reduction in the burden on health carers and family, and the ability to continue other work.23 Major cost savings (56%) were reported in a retrospective review carried out in the UK in administering home chemotherapy over a 1-year period compared to in-hospital treatment.28

Conclusion

Today, improvement in the quality of care for cancer patients through a patient-centered approach is seen as a strategic priority. Patient-centered care is based on patients’ needs rather than on prognosis. The delivery of oncology care at home is increasingly viewed as a way of improving quality of care and as a cost-effective alternative to inpatient hospital treatment for selected groups of patients. In fact the primary setting for the delivery of care to patients with cancer has shifted from the hospital to the home as a result of increased use of outpatient services for cancer treatment, the advent of oral therapies, shortened hospital visits, longer survival, and the trend for caregivers to accommodate patients’ desire to be cared for at home for as long as possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the GSTU Foundation for cancer care and the Sicilian Section of the GOIM (Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale) for supporting elaboration and publishing expenses of this paper.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Ward E, Thun M. Declining death rates reflect progress against cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E National Cancer Policy Board. Committee on cancer survivorship: improving care and quality of life. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiello Bowles EJ, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, et al. Understanding high-quality cancer care: a summary of expert perspectives. Cancer. 2008;112(4):934–942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederhuber JE. Facilitating patient-centered cancer research and a new era of drug discovery. The Oncologist. 2009;14(4):311–312. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobias JS, Hamilton RD. Prospective clinical trials as a model for patient-centred care. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(11):1695–1696. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein RM, Street RL. the values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):108–116. doi: 10.1370/afm.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007. [Accessed September 8, 2011]. Available at: http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org/downloads/pdfs/JointStatement.pdf.

- 11.McCorkle RE, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glajchen M. The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(2):145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepucha KR, Barry MJ. Making patients-centered cancer care a reality. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5610–5611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):155–164. doi: 10.1370/afm.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, Georgiadou F, Moinpour C, Goodell B. A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer. 1989;64(6):1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890915)64:6<1375::aid-cncr2820640634>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moller H, Fairley L, Coupland V, et al. The future burden of cancer in England: incidence and numbers of new patients in 2020. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(9):1484–1488. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Neill C, Wallis C. Home healthcare: emerging evidence for NHS Commissioners. J Care Serv Manag. 2009;3:357–363. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall M, Lloyd H. Evaluating patients’ experience of home and hospital chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2008;7:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boothroyd L, Lehoux P. Cancer chemotherapy at home: feasibility, patient outcomes and healthcare system implications [abstract] International Society of Technology Assessment in Health Care Meeting. 2003;9 abst 176. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweeney L, Halpert A, Waranoff J. Patient-centered management of complex patients can reduce costs without shortening life. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(2):84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rischin D, White M, Matthews J, et al. A randomised crossover trial of chemotherapy in the home: patient preference and cost analysis. Med J Austr. 2000;173(3):125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sprandio JD. Oncology patient-centered medical home and accountable cancer care. Commun Oncol. 2010;7(12):565–572. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(1):56–66. doi: 10.3322/caac.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(Suppl 3):S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raphael R, Yves D, Giselle C, Magali M, Odile CM. Cancer treatment at home or in hospital: what are the costs for French public health insurance? findings of a comprehensive-cancer centre. Health Policy. 2005;72(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wechalekar A, Kirk S, Dillon B, Ganczakowski M, Cranfield T. Home chemotherapy for haematological malignancies – an initial experience. Br J Haemat. 2000;108(Suppl 1):24. [Google Scholar]