Abstract

Whereas the role of Metabolic Syndrome (MS), and a high fat diet in prostate cancer (PCa) risk is still a matter of intense debate, it is becoming increasingly clear that obesity can cause perturbations in metabolic pathways that contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of PCa. Moreover, prostate epithelial cells per se undergo a series of metabolic changes, including an increase in de-novo lipogenesis, during the process of tumor formation. These metabolic alterations, at both the cellular and organismal levels, are intertwined with genetic aberrations necessary for neoplastic tranformation. Thus, altered metabolism is currently subject to intense research efforts and might provide preventative and therapeutic opportunities, as well as a platform for biomarker development. In this article, we review evidence that the metabolic sensor 5’-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which physiologically integrates nutritional and hormonal signals and regulates cell survival and growth-related metabolic pathways to preserve intracellular ATP levels, represents a link between energy homeostasis and cancer. Thus, when AMPK is not activated, as in the setting of MS and obesity, systemic metabolic alterations permissive to the development of PCa are allowed to proceed unchecked. Hence, the use of AMPK activators and inhibitors of key lipogenic enzymes may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for PCa.

BACKGROUND

Prostate Cancer (PCa) is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in industrialized countries. The main risk factors for this disease are age, black race, family history. Patients with metastatic PCa initially respond to androgen deprivation (AD) therapy for a median time of 12–18 months (1), following which the majority of patients relapse with castrate-resistant disease, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Chemotherapeutic treatment options for castrate-resistant PCa have a very modest palliative and survival benefit, so there is clearly an urgent need for additional therapies.

In the era of targeted therapies, many clinical trials have been conducted to test targeted drugs in PCa with the objective of studying their effects either on advanced metastatic disease or on primary tumor (neoadjuvant and surveillance trials). There is now growing interest in targeting metabolic pathways that may be altered during prostate tumorigenesis and PCa progression.

This review briefly discusses the impact of high-fat diet and the Metabolic Syndrome (MS) as well as obesity on PCa risk. In addition, some potential mechanistic aspects and intracellular metabolic consequences that might contribute to prostatic carcinogenesis will be discussed. In particular, activation of lipid metabolism has been described in most localized and metastatic prostate tumors, underscoring its potential role in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Here, we describe the crucial role of AMPK as master regulator of lipogenic pathways as well as of intracellular oncogenic signaling [i.e. mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway]. We therefore propose the activation of AMPK as a potential therapeutic strategy in PCa.

ON THE HORIZON

Dietary intervention

The incidence and disease-specific mortality of PCa show marked geographic variation, being greatest in North America and Western Europe, and lowest in Asia (2). These differences undoubtedly have a genetic component, but the relative contribution of diet and the “Western lifestyle” to PCa development has not been elucidated (3). Numerous epidemiological studies support an association between dietary fat intake (particularly saturated fats) and PCa risk (4, 5), unfavorable prognosis, and relapse after treatment for localized PCa (6). In addition, differential gene expression of human prostate xenografts from mice under high-fat diet, showed significant upregulation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R), a known driver of prostatic carcinogenesis, compared to mice under low-fat diet (7). Importantly, however, activating mutations in the IGF-1/phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway may influence the response of cancers to dietary restriction-mimetic therapies (8). Nevertheless, more recent studies seem to refute these previous observations (9, 10). Thus, the existence of a relationship between fat intake and PCa risk still remains an intriguing open question.

The influence of dietary fat on PCa has been linked to specific fatty acids (FA): several in-vivo studies have indicated that low-fat diets high in omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated FA (PUFAs) reduce the development and progression of PCa, whereas high-fat diets rich in omega-6 (n-6) promote the growth and proliferation of PCa cells (11). Since the “Western diet” contains a disproportionally high n-6/n-3 ratio, n-6 PUFAs are likely to be critical modulators of human prostate carcinogenesis. The tantalizing epidemiological data, combined with the positive effects of n-3 PUFAs in cell culture and animal models, prompted the development of clinical trials using n-3 PUFAs in the prevention and treatment of PCa (http://clinicaltrials.gov/). To date, five clinical trials (NCT0099674, NCT00253643, NCT00458549, NCT00433797, and NCT00402285) are ongoing, and one (NCT00049309) has been successfully completed showing that flaxseed supplementation reduces PCa proliferation rates in men presurgery (12).

Obesity, Metabolic syndrome and PCa

Epidemiological studies

In spite of the controversial association between high-fat diet and PCa risk, there is mounting epidemiologic evidence for a relationship between obesity and PCa progression. Obesity has been identified as an important adverse prognostic factor for PCa (13). Moreover, population studies have revealed that PCa patients with higher serum levels of insulin or c-peptide are at increased risk of adverse outcome (14). The mechanism that underlies the association between obesity and PCa is not clear, but insulin-mediated increase of IGF-1 and the subsequent activation of PI3K/mTOR pathway have been suggested (15). Obesity has also been associated with decreased serum levels of the adipocytes-secreted cytokine adiponectin. Recent epidemiological studies showed an inverse correlation between adiponectin levels and the risk of PCa (16, 17) and in vitro studies confirmed adiponectin’s inhibitory effect on PCa cell growth through activation of AMPK (see below) (18). Moreover, abdominal obesity is frequently associated with MS, a state of metabolic dysregulation characterized mainly by insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and predisposition to type II diabetes (19). Even if some studies have shown its association with a higher risk of PCa (20–22), the results are still inconclusive (23, 24). This may be due to a lack of unambiguous definition of MS, differences in age at baseline measurement and length of follow up. In fact, a recent study of ours has shown that MS as defined by strict accepted international definitions, is significantly associated with prostate cancer mortality when the competing risk of early death from other causes, is taken into account (25).

5’-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

AMPK is a highly conserved energy-sensing serine/threonine kinase, consisting of a α catalytic subunit and regulatory β and γ subunits. At the cellular level, AMPK is activated by metabolic stressors that deplete ATP and increase AMP (e.g. exercise, hypoxia, glucose deprivation). At the level of the organism, enzyme activity is also under the control of hormones and cytokines, such as adiponectin and leptin (26). Activation of AMPK reduces plasma insulin levels, suppresses ATP-consuming metabolic functions (such as synthesis of FAs, sterols, glycogen, and proteins), and increases ATP-producing activities (glucose uptake, FA oxidation, and mitochondrial biogenesis) to restore energy homeostasis. Thus, AMPK functions as a central metabolic switch that governs glucose and lipid metabolism.

Decreased AMPK activity has been found to contribute to the metabolic abnormalities involved in MS (15, 27). Moreover, a recent study revealed an association between polymorphisms in the PRKAA2 gene (encoding the α2 subunit of AMPK, which is responsible for the MS phenotype) (28) and susceptibility to insulin resistance and diabetes in the Japanese population (29). Interestingly, the same locus correlates with PCa risk (30), suggesting that AMPK dysregulation may provide a mechanistic link between MS and PCa. Consequently, drugs that ameliorate MS conditions through AMPK activation (Table 1) may be beneficial for PCa prevention and treatment.

Table 1.

Current direct and indirect AMPK activators

| Activator | Effect on AMPK | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Metformin | indirect | Increase AMP/ATP by inhibition of complex 1 of mitochondrial respiratory chain |

| TZDs* | indirect | Increase PPARγ-mediated release of adiponectin, which consequently activates AMPK |

| Deguelin | indirect | Not fully clarified. Decrease of ATP |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | indirect | Activation of the AMPK activator CaMKK** |

| Barberin | indirect | Increase AMP/ATP by inhibition of mitochondrial function |

| α-Lipoic acid | indirect | n.d. |

| Resveratrol | indirect | Not fully clarified. Possible activation of SIRT1*** and consequent deacetylation of the AMPK activator LKB1 |

| AICAR **** | direct | AMP mimetic |

| A-769662 | direct | Allosteric binding of β1 AMPK subunit |

| PT1 | direct | Allosteric binding of α1 AMPK subunit |

n.d.= not determined yet,

TZDs= thazolidinediones,

CAMKK= Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase,

SIRT1= sirtuin 1,

AICAR= 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-b-riboside.

Metformin: current and new prospectives

Metformin is a biguanide used as mainstream therapy for type II diabetes for its insulin-sensitizing effects. It has been shown to prevent or delay the onset of MS (31). Recent evidence indicates that: a) diabetics under treatment with metformin show a reduced cancer incidence (32) and cancer-related mortality compared to patients exposed to sulfonylureas or insulin (33); b) metformin use is associated with a 44% risk reduction in PCa cases compared to controls in Caucasian men (34); c) breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and metformin have significantly higher pathologic complete responses than patients not taking metformin (retrospective study) (35). Thus, its potential antineoplastic activity has been proposed and it is currently under investigation. These human studies are further supported by studies in vitro and in xenograft models, showing its antitumor activity on PCa cells (18, 36) and by the exciting discovery that metformin is able to selectively kill cancer stem cells from 4 genetically distinct breast cancer lines (37). The mechanism of action for metformin’s anti-tumor effect is not completely understood and has been ascribed to both direct and indirect effect. Metformin’s direct effects on tumor have been partly attributed to AMPK activation (38). At millimolar concentrations, metformin inhibits complex I of the respiratory chain resulting in increased AMP/ATP ratio and secondary activation of the AMPK pathway (39). This results in inhibition of mTOR and p70S6kinase 1 (S6K1) activity and decreased translational efficiency in PCa cell lines (36). However, inhibition of AMPK using siRNA did not prevent the antiproliferative effect of metformin in PCa cell lines, suggesting that its effects can be independent of AMPK. This could be partly explained by induction of G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, which was accompanied by a strong decrease in cyclin D1 protein level, pRb phosphorylation and an increase in p27kip protein expression (36). In vitro studies have also shown that metformin may inhibit tumor growth by preventing p53-induced autophagy (40) and its treatment has an inhibitory effect on nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and extracellular regulated-signal kinase (Erk) 1/2 activation by an AMPK-independent mechanism (41). Metformin’s indirect effect on tumor proliferation can be explained via inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, thereby decreasing circulating glucose, insulin and IGF-1 levels, and resultant signaling flux through the insulin/IGF-1 pathway (42).

Understanding how biguanides mediate their anti-cancer effect is critical before launching clinical trials for advanced disease. If anti-tumor effects are mediated by AMPK pathway, a specific group of PCa patients with low AMPK activation might be targeted in clinical trials with biguanides. Alternatively, if the anti-tumor effects of biguanides are predominantly by an indirect mechanism, then PCa patients most likely to benefit might be those with concomitant insulin resistance. Therefore, although metformin is very safe and remarkably inexpensive, it is critical to understand its mechanism of action in PCa before embarking on trials in metastatic disease.

A phase II clinical trial is currently ongoing to study the effect of neoadjuvant metformin therapy in PCa patients prior to radical prostatectomy (NCT00881725). In addition, a randomized phase II surveillance trial to test the combinatorial effect of the 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride and metformin in low risk PCa patients, not previously treated, has also been planned at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

Anti-metabolic approaches to target PCa cells

Prostate cancer cell likely require specific metabolic alterations that cooperate with “driver” genetic events to effect neoplastic transformation and tumor progression. Increased aerobic glycolysis has been found only in advanced disease whereas exacerbation of de-novo FA and sterol synthesis due to overexpression of key enzymes [ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), fatty acid synthase (FASN), 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA reductase)] and increased protein synthesis due to hyperactivation of mTOR are common features of both primary and advanced PCa (43–46). These alterations are induced both by androgens and by the activated PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, deregulated in a significant number of PCa. Indeed, deletions/mutations in the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) are found in 30% of primary PCa and in over 60% of metastatic PCa (47). Hence, inhibitors of mTOR and PI3K, alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic agents, are being tested in hormone-refractory PCa (48). At the same time, the observation of increased de-novo FA and sterol synthesis has led to increasing efforts to develop inhibitors of these metabolic pathways.

Inhibitors of lipogenesis

ACC, FASN and HMG-CoA reductase are responsible for the synthesis of malonyl-CoA, the saturated FA palmitate, and mevalonate (the precursor of cholesterol), respectively and their role in the pathogenesis and progression of PCa is well established (49, 50). Small molecule FASN inhibitors (cerulein, C75, C93, Orlistat), HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), and ACC inhibitors (such as soraphen A) have shown promising preclinical results both in vitro and in vivo (51–53). So far, the use of FASN inhibitors as systemic drugs has been hampered by pharmacologic limitations and side effects (weight loss) (51). However, recent reports have described new potent FASN inhibitors identified through high-throughput screening as a testimony of the continuous interest for FASN as a therapeutic target (51). Moreover, recent data showed a reduced incidence of PCa among statin users in the Finnish Prostate Cancer Screening Trial, associated with lower PSA levels (54). This evidence suggests that interfering with lipid metabolism represents an important direction to pursue. At present, two clinical trials are ongoing to investigate the effect of statin therapy prior prostatectomy (NCT00572468) or during external beam radiation therapy (NCT00580970). A more accurate stratification of patients eligible for lipogenic pathways-inhibiting therapies could be achieved thanks to the increasing development of new positron emission tomography (PET)-based metabolic imaging techniques. In fact, lipid metabolism is being investigated by 11[C]- and 18[F]-labeled acetate or choline. Both these tracers have shown increased sensitivity in the detection of both primary, recurrent and metastasic PCa (55).

Direct AMPK activators

One of the major impediments in the development of targeted therapies is the crosstalk between multiple signaling and metabolic pathways that can result in functional redundancy to maintain cell growth and survival circuits. One strategy to overcome this obstacle is represented by the combinatorial approach to targeted therapies. Another approach may be to target a master regulatory switch of major oncogenic signaling and metabolic pathways, such as AMPK.

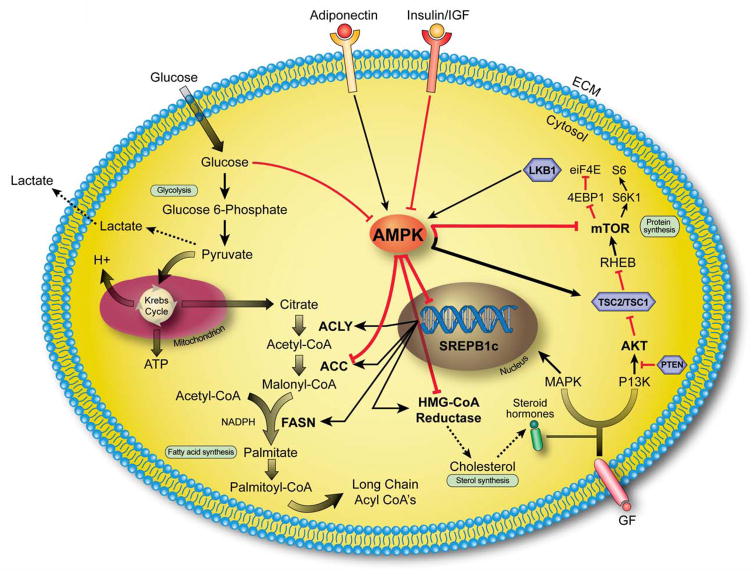

The major kinase involved in AMPK activation is the well-known tumor suppressor LKB1 (56). LKB1 germ-line mutations are responsible for Peutz-Jegher syndrome, predisposing carriers to hamartomas and a variety of malignant epithelial tumors (57). Interestingly, over 80% of LKB-1 knock out mice appear to develop prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (58). This suggests that the LKB1-AMPK pathway may act as the link between cancer and energy homeostasis. Indeed, when physiologically or pharmacologically activated, AMPK acts in a tumor suppressor-like fashion. It inhibits key lipogenic enzymes by direct phosphorylation (ACC, HMG-CoA reductase) or by transcriptional regulation (ACLY, FASN) through the suppression of the transcriptional factor Sterol Regulator Element Binding Protein 1 (SREBP-1). In addition, AMPK inhibits the mTOR pathway through direct phosphorylation of Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 protein and the mTOR-associated factor Raptor (Figure 1). Finally, it induces cell cycle arrest or apoptosis through phosphorylation of p53 and FOXO3a (59). Thus, activated AMPK can switch off multiple oncogenic pathways at once. In particular, it may simultaneously inhibit the two major pathways (lipogenic and PI3K/mTOR pathways) that drive PCa carcinogenesis antagonizing the activity of Akt at multiple levels (SREBP-1, TSC-2, and mTOR complex 1 level). Consequently, AMPK activators, overcoming the feedback activation loop of Akt following long-term mTORC1 inhibition (likely responsible for the clinical failure of mTORC1 inhibitor Rapamycin) (60), may be effective in metastatic PCa harboring PTEN deletions. Hence, intense efforts are being made to directly activate AMPK. The direct AMPK activator Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR), an AMP mimetic, has been shown to inhibit PCa cells proliferation (61) and tumor growth in PCa xenograft models (36). However, AICAR is not entirely specific for AMPK, it has limited oral bioavailability and frequently induces an increase in blood levels of lactic acid and uric acid. The possibility of novel small molecules able to allosterically activate AMPK has been greatly fostered by the recent publication of the crystal structure of AMPK’s subunits (62). Abbott laboratories has pioneered this area and identified A-769662, a thinopyridone AMPK activator that activates the enzyme by binding the β1 subunit (63). A-769662 has been shown to delay tumor development and decrease tumor incidence in PTEN+/− mice with a hypomorphic LKB1 allele (64). A second small molecule activator (PT1), not yet well characterized, has also been recently reported (65).

Figure 1. AMPK controls main metabolic pathways in PCa cells.

PCa cells are characterized by exacerbation of lipogenesis associated with hyperactivation of mTOR pathway. Activation of AMPK can inhibit these pathways by direct phosphorylation of key lipogenic enzymes [ACC, in particular isoform 1, HMG-CoA reductase} and key kinases (the complex TSC1/TSC2 and the mTOR-associated factor Raptor) or by regulating transcription through SREBP1c. Red and black arrows indicate activation and inhibition, respectively. Tumor suppressor genes are represented in violet hexagonal boxes. AMPK= AMP-activated protein kinase, SREBP1c= Sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c, ACLY=ATP citrate lyase, ACC= Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, FASN= Fatty acid synthase, HMG-CoA reductase=3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase, MAPK= mitogen-activated protein kinase, PI3K= phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, PTEN= phosphatase and tensin homolog, TSC2/TSC1= tuberous sclerosis complex 1/2, RHEB= Ras homolog enriched in brain, mTOR= mammalian target of rapamycin, 4EBP1= 4E-binding protein 1, S6K1= S6 kinase 1, eiF4E= Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4, GF=growth factors.

CONCLUSION

The current paradigm in personalized cancer therapeutics is to target oncogene-addicted pathways in individual tumors. As highlighted in this review, the cellular and whole-organism metabolic milieu can be exploited to interfere with PCa cells using a “synthetic lethal” strategy by combining inhibitors of metabolic enzymes with targeted inhibitors of mutated oncogenes. Furthermore, obtaining broad-based metabolite profiling of prostate tumors by mass spectrometry and/or nuclear magnetic resonance technologies will help develop novel functional PCa classifications based on deregulated metabolic pathways. This, in combination with genetic and proteomic mapping, could be exploited to achieve more accurate subclassification of PCa, new metabolism-based functional imaging techniques, as well as more effective therapies based on targeting metabolic enzymes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jane Hayward and Michael Cichanowski for their graphic assistance. We also thank Cornelia Photopoulos and Stefano Duga for their technical support.

This work was supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the National Cancer Institute (RO1CA131945, PO1CA89021, and P50 CA90381), and the Linda and Arthur Gelb Center for Translational Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial or competing interests to declare.

Bibliography

- 1.Mahler C, Denis LJ. Hormone refractory disease. Semin Surg Oncol. 1995;11:77–83. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980110112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsing AW, Devesa SS. Trends and patterns of prostate cancer: what do they suggest? Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mistry T, Digby JE, Desai KM, Randeva HS. Obesity and prostate cancer: a role for adipokines. Eur Urol. 2007;52:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective study of dietary fat and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1571–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.19.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, Wu AH, et al. Prostate cancer in relation to diet, physical activity, and body size in blacks, whites, and Asians in the United States and Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:652–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strom SS, Yamamura Y, Forman MR, Pettaway CA, Barrera SL, DiGiovanni J. Saturated fat intake predicts biochemical failure after prostatectomy. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2581–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narita S, Tsuchiya N, Saito M, et al. Candidate genes involved in enhanced growth of human prostate cancer under high fat feeding identified by microarray analysis. Prostate. 2008;68:321–35. doi: 10.1002/pros.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalaany NY, Sabatini DM. Tumours with PI3K activation are resistant to dietary restriction. Nature. 2009;458:725–31. doi: 10.1038/nature07782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Murphy SP, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Fat and meat intake and prostate cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(6):1339–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowe FL, Key TJ, Appleby PN, Travis RC, Overvad K, Jakobsen MU, Johnsen NF, Tjønneland A, Linseisen J, Rohrmann S, Boeing H, Pischon T, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Sacerdote C, Palli D, Tumino R, Krogh V, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kiemeney LA, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Sánchez MJ, Larrañaga N, González CA, Quirós JR, Manjer J, Wirfàlt E, Stattin P, Hallmans G, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Riboli E. Dietary fat intake and risk of prostate cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1405–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berquin IM, Min Y, Wu R, et al. Modulation of prostate cancer genetic risk by omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1866–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI31494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demark-Wahnefried W, Polascik TJ, George SL, et al. Flaxseed supplementation (not dietary fat restriction) reduces prostate cancer proliferation rates in men presurgery. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3577–87. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedland SJ. Obesity and prostate cancer: a growing problem. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6763–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B. Hyperinsulinaemia: a prospective risk factor for lethal clinical prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2887–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Z, Saha AK, Xiang X, Ruderman NB. AMPK, the metabolic syndrome and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michalakis K, Williams CJ, Mitsiades N, et al. Serum adiponectin concentrations and tissue expression of adiponectin receptors are reduced in patients with prostate cancer: a case control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:308–13. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Stampfer MJ, Mucci L, et al. A 25-year prospective study of plasma adiponectin and leptin concentrations and prostate cancer risk and survival. Clin Chem. 56:34–43. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.133272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zakikhani M, Dowling RJ, Sonenberg N, Pollak MN. The effects of adiponectin and metformin on prostate and colon neoplasia involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:369–75. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laukkanen JA, Laaksonen DE, Niskanen L, Pukkala E, Hakkarainen A, Salonen JT. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of prostate cancer in Finnish men: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1646–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund Haheim L, Wisloff TF, Holme I, Nafstad P. Metabolic syndrome predicts prostate cancer in a cohort of middle-aged Norwegian men followed for 27 years. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:769–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beebe-Dimmer JL, Dunn RL, Sarma AV, Montie JE, Cooney KA. Features of the metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer in African-American men. Cancer. 2007;109:875–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tande AJ, Platz EA, Folsom AR. The metabolic syndrome is associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164 (11):1094–102. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin RM, Vatten L, Gunnell D, Romundstad P, Nilsen TI. Components of the metabolic syndrome and risk of prostate cancer: the HUNT 2 cohort, Norway. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1181–92. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundmark B, Garmo H, Loda M, Busch C, Holmberg L, Zethelius B. The metabolic syndrome and the risk of prostate cancer under competing risks of death from other causes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0112. (in final revision) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–85. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruderman N, Prentki M. AMP kinase and malonyl-CoA: targets for therapy of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:340–51. doi: 10.1038/nrd1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viollet B, Andreelli F, Jorgensen SB, et al. Physiological role of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK): insights from knockout mouse models. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:216–9. doi: 10.1042/bst0310216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horikoshi M, Hara K, Ohashi J, et al. A polymorphism in the AMPKalpha2 subunit gene is associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetes. 2006;55:919–23. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui H, Suzuki K, Ohtake N, et al. Genomewide linkage analysis of familial prostate cancer in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, et al. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: the Diabetes Prevention Program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:611–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330:1304–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:254–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1617–22. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiralerspong S, Palla SL, Giordano SH, et al. Metformin and pathologic complete responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in diabetic patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3297–302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.19.6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27:3576–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Metformin selectively targets cancer stem cells, and acts together with chemotherapy to block tumor growth and prolong remission. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7507–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardie DG. Neither LKB1 nor AMPK are the direct targets of metformin. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:973. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, et al. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan BK, Adya R, Chen J, et al. Metformin decreases angiogenesis via NF-kappaB and Erk1/2/Erk5 pathways by increasing the antiangiogenic thrombospondin-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:566–74. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauer DE, Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Andreadis C, Thompson CB. ATP citrate lyase is an important component of cell growth and transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24:6314–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swinnen JV, Vanderhoydonc F, Elgamal AA, et al. Selective activation of the fatty acid synthesis pathway in human prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:176–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001015)88:2<176::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi S, Graner E, Febbo P, et al. Fatty acid synthase expression defines distinct molecular signatures in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:707–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ettinger SL, Sobel R, Whitmore TG, et al. Dysregulation of sterol response element-binding proteins and downstream effectors in prostate cancer during progression to androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2212–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-2148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sellers WR, Sawyers CL. Somatic Genetics of Prostate Cancer: Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarker D, Reid AH, Yap TA, de Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4799–805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Migita T, Ruiz S, Fornari A, et al. Fatty acid synthase: a metabolic enzyme and candidate oncogene in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:519–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flavin R, Peluso S, Nguyen PL, Loda M. Fatty Acid Synthaseas a Potential Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Fut Oncol. 2010;6:551–62. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murtola TJ, Visakorpi T, Lahtela J, Syvala H, Tammela T. Statins and prostate cancer prevention: where we are now, and future directions. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:376–87. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beckers A, Organe S, Timmermans L, et al. Chemical inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase induces growth arrest and cytotoxicity selectively in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8180–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murtola TJ, Tammela TL, Maattanen L, et al. Prostate cancer and PSA among statin users in the finnish prostate cancer screening trial. Int J Cancer. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Picchio M, Crivellaro C, Giovacchini G, Gianolli L, Messa C. PET-CT for treatment planning in prostate cancer. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;53:245–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woods A, Johnstone SR, Dickerson K, et al. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2004–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, Friedel W, Loff S, Jeschke R, Müller O, Back W, Zimmer M. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet. 1998;18:38–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearson HB, McCarthy A, Collins CM, Ashworth A, Clarke AR. Lkb1 deficiency causes prostate neoplasia in the mouse. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2223–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ. The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:563–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, Grohar P, Helman LJ. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of Akt signaling through an IGF-1R-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2007;26:1932–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xiang X, Saha AK, Wen R, Ruderman NB, Luo Z. AMP-activated protein kinase activators can inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao B, Heath R, Saiu P, et al. Structural basis for AMP binding to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2007;449:496–500. doi: 10.1038/nature06161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cool B, Zinker B, Chiou W, et al. Identification and characterization of a small molecule AMPK activator that treats key components of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2006;3:403–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang X, Wullschleger S, Shpiro N, et al. Important role of the LKB1-AMPK pathway in suppressing tumorigenesis in PTEN-deficient mice. Biochem J. 2008;412:211–21. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pang T, Zhang ZS, Gu M, et al. Small molecule antagonizes autoinhibition and activates AMP-activated protein kinase in cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16051–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710114200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]