Abstract

Skeletal muscle expresses prion protein (PrP) that buffers oxidant activity in neurons.

Aims

We hypothesize that PrP deficiency would increase oxidant activity in skeletal muscle and alter redox-sensitive functions, including contraction and glucose uptake. We used real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blot analysis to measure PrP mRNA and protein in human diaphragm, five murine muscles, and muscle-derived C2C12 cells. Effects of PrP deficiency were tested by comparing PrP-deficient mice versus wild-type mice and morpholino-knockdown versus vehicle-treated myotubes. Oxidant activity (dichlorofluorescin oxidation) and specific force were measured in murine diaphragm fiber bundles.

Results

PrP content differs among mouse muscles (gastrocnemius>extensor digitorum longus, EDL>tibialis anterior, TA; soleus>diaphragm) as does glycosylation (di-, mono-, nonglycosylated; gastrocnemius, EDL, TA=60%, 30%, 10%; soleus, 30%, 40%, 30%; diaphragm, 30%, 30%, 40%). PrP is predominantly di-glycosylated in human diaphragm. PrP deficiency decreases body weight (15%) and EDL mass (9%); increases cytosolic oxidant activity (fiber bundles, 36%; C2C12 myotubes, 7%); and depresses specific force (12%) in adult (8–12 mos) but not adolescent (2 mos) mice.

Innovation

This study is the first to directly assess a role of prion protein in skeletal muscle function.

Conclusions

PrP content varies among murine skeletal muscles and is essential for maintaining normal redox homeostasis, muscle size, and contractile function in adult animals. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 2465—2475.

Introduction

The prion protein (PrP) is a glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol (GPI)-anchored glycoprotein that is expressed in vertebrates and is highly conserved among mammals. It is most abundant in neuronal tissue but is also expressed in other tissues, including lung, kidney, gastrointestinal mucosa, mammary glands, lymphoid cells, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle (18). PrP is associated with transmissible spongiform encephalopathies that occur in taxonomically diverse species, including sheep (scrapie), cattle (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), cervids (chronic wasting disease), and humans (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease). In these degenerative neurological diseases, the normal cellular form of PrP (also known as PrPc) undergoes a conformational change to a proteinase-resistant form, referred to as PrPSc. This infectious conformer facilitates further conversion of PrP to PrPSc.

Innovation

Previous studies have demonstrated that the prion protein (PrP) has the capacity to modulate redox homeostasis and acts as an antioxidant, primarily in neural tissues. Other investigators have shown that PrP is differentially expressed in skeletal muscle and that PrP deficiency is associated with a decrease in performance in certain physical activities. The present study is the first to examine the direct effects of prion deficiency on oxidant activity, muscle mass, glucose transport, and contractile function ex vivo. The results indicate that PrP plays an important role in maintaining normal muscle size and function, possibly through redox-dependent pathways.

The physiological significance of normal cellular PrP is poorly understood but is thought to play roles in cell adhesion and extracellular matrix-related signaling (13), neurogenesis and differentiation (44), copper homeostasis (16), synaptogenesis (19), and cell survival (14). Other studies indicate a role in cellular defense against oxidative stress. PrP-deficient cells are more susceptible to treatment with hydrogen peroxide and xanthine oxidase (4, 5). The brains of PrP-deficient mice exhibit increased protein carbonylation and lipid peroxidation (49). Klamt et al. (20) have documented decreased activity of two important antioxidant enzymes, CuZn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and catalase, in tissues of PrP-deficient mice. The mechanism of PrP protection against biological oxidants is not well defined but may involve cellular processing of metal ions such as copper (15), manganese (8), and iron (43).

The role of PrP in skeletal muscle is largely unexplored. Massimino and associates (24) have shown that PrP expression in cultured myotubes increases with maturation and in murine muscle is age- and fiber type-dependent. Also, myopathic changes can be induced by overexpression of wild-type (48) or certain mutant PrP transgenes (47). PrP supports redox homeostasis in nonmuscle cell types (above), and both contractile function (21, 37) and glucose uptake (40) are redox-sensitive in skeletal muscle. Thus, constitutive PrP is predicted to influence muscle performance. The behavior of PrP-deficient mice supports this prediction. Compared to wild-type controls, Nico et al. (30) found that PrP-deficient animals have lower swimming capacities and less locomotor activity after bouts of forced exercise. In a separate study (31), the authors challenged mice with forced swimming under different loads and found that PrP-deficient animals could swim for less time. These data suggest PrP is essential for normal exercise performance but do not identify the organ(s) impaired by PrP deficiency (e.g., skeletal muscle, nervous system, cardiovascular, or pulmonary tissue).

In the current study, we evaluated PrP expression patterns across murine muscles, in human diaphragm, and a muscle-derived cell line. We also evaluated the functional importance of PrP by testing three hypotheses: a) PrP is essential for redox homeostasis in skeletal muscle and cultured myotubes; b) PrP deficiency depresses contractile function; and c) glucose uptake is increased in PrP-deficient muscle. Our results show that PrP isoform expression and glycosylation patterns vary among muscles; expression levels are also influenced by age and differentiation state. Functional studies identify PrP as an essential modulator of redox homeostasis and contractile function in skeletal muscle. The data do not support a role for PrP in glucose uptake.

Results

PrP expression in skeletal muscle.

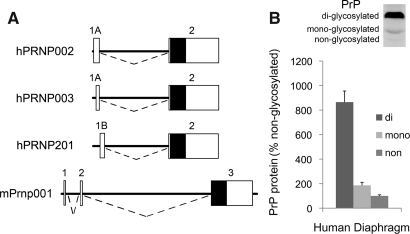

The human PrP gene (PRNP) expresses two alternative first exons, 1A vs. 1B, and a common second exon that contains the PrP coding sequence (Fig. 1A). To evaluate PrP expression in human skeletal muscle (diaphragm), we initially used PCR to amplify from the alternatively spliced exon 1A or 1B to the common exon 2. PCR products were ligated into pcDNA2.1 and eight clones were isolated and sequenced. The major PrP isoform arising from exon 1A is PRNP002 (seven clones), whereas a single clone corresponded to PRNP003. We also detected a PCR product arising from exon 1B and corresponding to PRNP201 but found no PCR products corresponding to PRNP202 or PRNP205.

FIG. 1.

PrP in human muscle. (A) Maps depict human PRNP and mouse Prnp transcripts; exons are represented by boxes; white areas correspond to untranslated regions, and black areas to protein-coding regions; introns are represented by dashed lines and are one-quarter scale relative to exons; three splice variants detected in human diaphragm are shown. (B) Western blot of PrP in human diaphragm; the chart shows average PrP glycoform levels from 9 individuals expressed as a percentage of nonglycosylated PrP.

To quantify PrP mRNA, we used RT-PCR relative to standard curves for the isoforms. The PCR reaction that measured hPRNP002 showed robust expression (i.e., 750 to 10,010 copies per cDNA sample). This represents over 98% of PrP mRNA. PCR products corresponding to other isoforms were minimal (e.g., 22–62 copies of PRNP201 per individual sample). Averaged among nine muscle samples, overall abundance of total PrP mRNA (all isoforms) relative to 18S mRNA was 7.1×10−6. We found no correlation between total PrP mRNA level or 18S mRNA level and postmortem interval (not shown).

Western blot analysis identified three bands corresponding to glycosylation states of the PrP protein (Fig. 1B). The monoclonal antibody used, 6D11, is effective in detecting PrPSc, PrPC, and recombinant PrP as well as all three glycoforms of PrP (35). The 36 kD di-glycosylated form is most prevalent in human muscle (8.6-fold greater than nonglycosylated form). Lesser fractions are mono-glycosylated (30 kD; 1.8-fold greater) or nonglycosylated (28 kD).

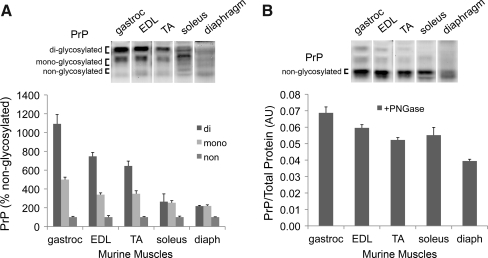

The mouse PrP gene (Prnp) codes for a single isoform in skeletal muscle that has 89% identity with hPRNP002 (Fig.1A). Analyses by quantitative RT-PCR indicate total PrP mRNA levels normalized for 18S mRNA are similar among murine soleus (9.5×10−6), EDL (7.3×10−6), and diaphragm (7.1×10−6), and are comparable to human diaphragm (above). At the protein level, PrP glycosylation profiles vary among murine muscles (Fig. 2A). We quantified PrP content, relative to total protein, using muscle extracts treated with peptide: N-glycosidase (PNGase) to remove N-linked oligosaccharide side chains. As seen in Figure 2B, PrP content of gastrocnemius exceeds that of diaphragm by more than 50%. The three remaining muscles have intermediate PrP levels.

FIG. 2.

Differences in PrP among murine muscles. (A) PrP Western blot of mouse muscle lysates; the chart shows PrP glycoform levels expressed as a percentage of nonglycosylated PrP. (B) PrP Western blot of muscle lysates following treatment with PNGase; the chart shows PrP levels expressed as a ratio to total protein. Abbreviations: diaph, diaphragm; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; gastroc, gastrocnemius; TA, tibialis anterior. Data are means±SE; n=4.

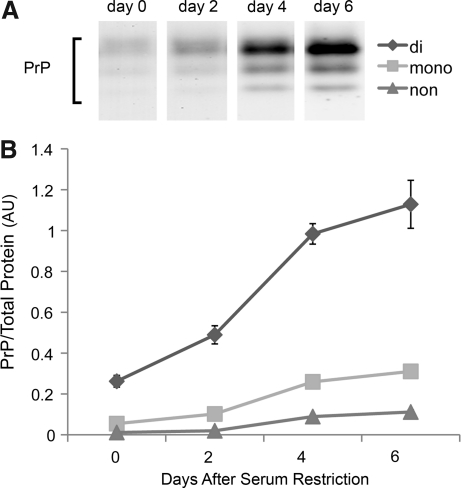

PrP expression during myotube differentiation

In C2C12 cells, serum restriction stimulates a well-defined program of proliferation, cell fusion, and differentiation over 6 days (42). During this period, we found that total content of all three prion glycoforms increases progressively (Fig. 3). The glycosylation profile of mature myotubes resembles that of human diaphragm and mouse limb muscle (i.e., the abundance of di-glycosylated prion exceeds that of the nonglycosylated form).

FIG. 3.

PrP increases with myotube differentiation. (A) PrP Western blot of whole cell extracts from differentiating C2C12 cells. (B) PrP glycoform levels expressed as a ratio to total protein. Data are means±SE; n=3.

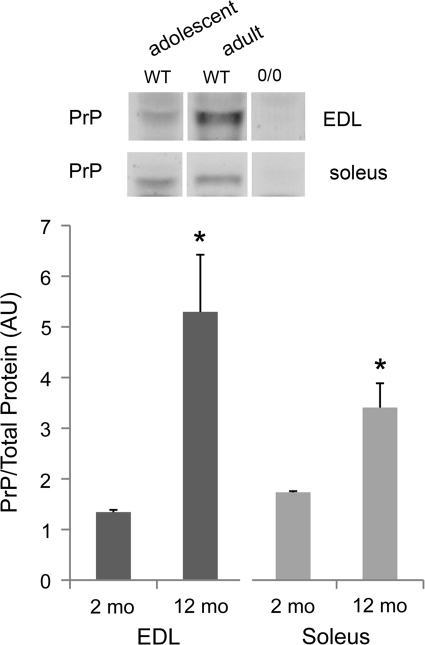

PrP and muscle mass in adult mice

PrP levels are relatively low in muscles of adolescent mice and do not obviously influence function. We detected no phenotype in adolescent PrP-deficient muscles using the current end-points (see below). PrP expression increases as mice mature; di-glycosylated PrP levels are four-fold greater in EDL and two-fold greater in soleus muscle of adult wild-type mice compared to adolescent animals (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

PrP expression with age. Western blot of diglycosylated PrP in muscle lysates from adolescent (2 months) and adult (8–12 months) mice; lysates from PrP-deficient (Prnp0/0) mice serve as a negative control; PrP levels expressed as a ratio to total protein; data are means±SE; n=3; *p<0.05 by t-test.

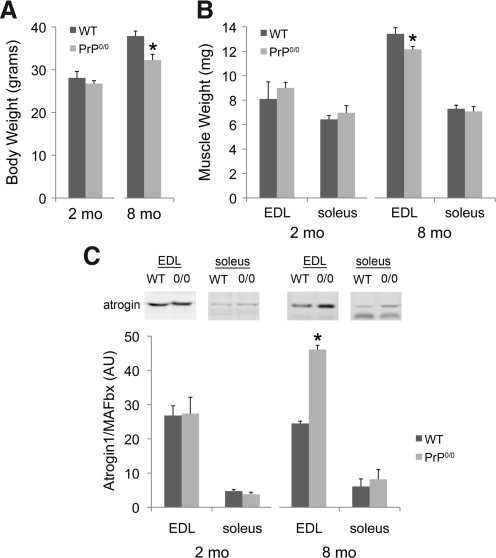

Studies of PrP-deficient mice (confirmed by Western blot; Fig. 4) suggest the PrP increase is essential for normal growth. Body weight of adult PrP-deficient animals is 15% less than age-matched genetic controls (Fig. 5A; 37.9 gm+1.2 vs. 32.2+1.4; p<0.05). In part, this is due to decrements in the weight of limb muscle (Fig. 5B; EDL; 13.4 mg+0.5 vs. 12.2+0.2; p<0.05). However, soleus weight was not affected (Fig. 5B). Follow-up studies tested for changes in atrogin1/MAFbx, a muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase and a biomarker for pro-catabolic gene expression. Atrogin1/MAFbx protein is elevated in EDL but not soleus of adult PrP-deficient mice (Fig. 5C), consistent with the observed reduction in EDL mass.

FIG. 5.

Muscle mass and atrogin1/MAFbx expression with PrP deficiency. (A) Changes in body weight with age in wild-type (WT) and Prnp0/0 mice. (B) Changes in muscle weight with age; data are means±SE; n=3 (2 mo) or 4 (8 mo); *p<0.05 by t-test. (C) Atrogin1/MAFbx Western blot of muscle lysates from 2 mo and 8 mo-old mice; the chart shows atrogin1/MAFbx expressed as a ratio to total protein; data are means±SE; n=3, *p<0.001 by t-test.

PrP deficiency depresses muscle function

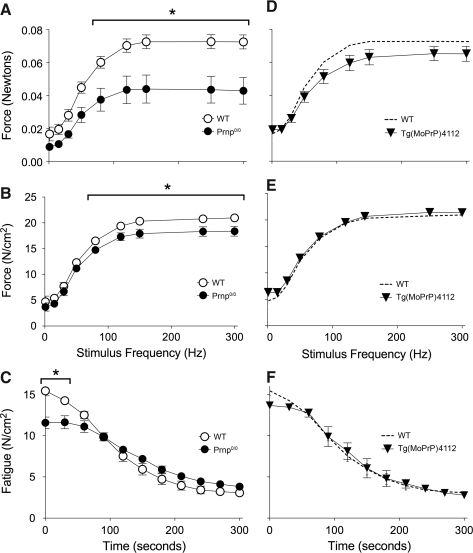

We evaluated PrP effects on contractile function of muscle fiber bundles from diaphragm of adult wild-type and PrP-deficient animals. Absolute force of unfatigued fiber bundles is depressed by 40% across a broad range of stimulation frequencies (Fig. 6A). This is due to parallel decrements in cross-sectional area (−29.7%, p<0.08) and specific force (Fig. 6B). Decrements in specific force persist throughout the first minute of repetitive contractions used to elicit fatigue (Fig. 6C). Transgenic expression of PrP on the knockout background rescues abnormalities in absolute force (Fig. 6D), cross-section (not shown), specific force (Fig. 6E), and fatigue (Fig. 6F).

FIG. 6.

Diaphragm dysfunction in PrP-deficient mice. Diaphragm from Prnp0/0 mice show decrements in (A) absolute force; (B) force per cross sectional area (specific force), and (C) fatigue. These decrements are rescued by PrP overexpression in the deficient animals (Tg(MoPrP)4112), (D, E, and F). Data are means±SE; n=4 (WT, Prnp0/0) or 3 (Tg(MoPrP)4112); *p<0.05 by two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test.

Redox homeostasis

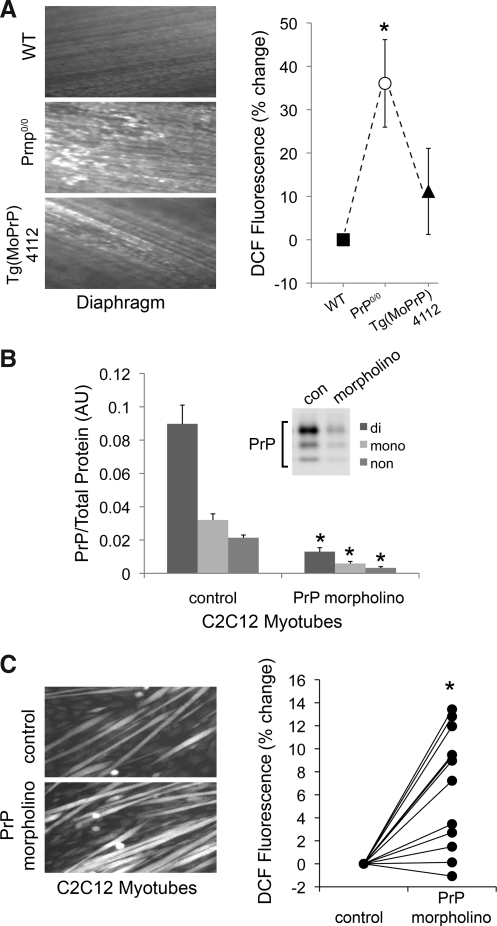

PrP is essential for redox homeostasis in nonmuscle cell types (4, 5, 20, 49). Our data suggest a similar role for PrP in skeletal muscle. PrP deficiency increases cytosolic oxidant activity in diaphragm muscle fibers by 35%, a loss of redox control that is rescued by transgenic PrP expression (Fig. 7A). A morpholino against PrP was used to lessen the content (∼87%) of all three glycoforms in mature C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 7B). As seen in adult muscle fibers, PrP deficiency also elevates cytosolic oxidant activity in this preparation (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Oxidant activity is elevated in PrP-deficient muscle. (A) Left panel: fluorescent images of diaphragms loaded with oxidant-sensitive probe (dichlorofluorescein, DCF, 20 μM, 60 min); right panel: percent change in fluorescence of transgenic mice relative to wild-type; means±SE; n=6 (WT vs. Prnp0/0) or 3 (WT vs. Tg(MoPrP)4112); *p<0.05 by paired t-test. (B) PrP Western blot of lysates from C2C12 myotubes following treatment with PrP morpholino (5 μM, 48 h); the chart shows a morpholino-induced decrease in PrP relative to total protein; means±SE; n=3; *p<0.001 by t-test. (C) Left panel: fluorescent images of C2C12 myotubes loaded with DCF (10 μM, 30 min); right panel: percent change in fluorescence of morpholino-treated myotubes relative to control; n=12; *p<0.001 by paired t-test.

NO regulation

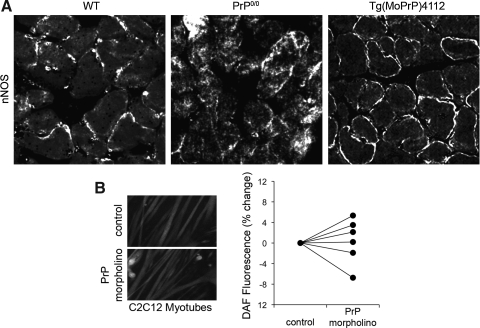

The neuronal-type NO synthase (nNOS) is constitutively expressed by skeletal muscle fibers and localizes to the sarcolemma (Fig. 8A). PrP deficiency alters nNOS localization, causing diffuse distribution within fibers. Localization is rescued by transgenic expression of PrP on the knockout background. Despite altered localization, PrP deficiency does not influence nNOS protein levels in diaphragm tissue (not shown) or basal NO activity within fibers (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

PrP deficiency and NO regulation. (A) Immunofluorescent detection of nNOS in frozen sections of mouse diaphragm (green, anti-nNOS; blue, DAPI). (B) Left panel: fluorescent images of C2C12 myotubes loaded with NO-sensitive probe (4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate, DAF, 5 μM, 30 min); right panel: percent change in fluorescence of PrP morpholino (5 μM, 48 h) treated myotubes relative to control, n=6.

Glucose uptake

Our observation that oxidant activity is elevated in PrP-deficient muscle fibers predicts that glucose uptake might also increase (7). This was not the case. PrP deficiency did not alter the rate of glucose uptake by adult murine EDL under basal conditions (p>0.90; overall mean=2.7 μmol/ml/h+0.3 SE) or after insulin stimulation (p>0.85; 5.0+0.9).

Discussion

The current study addresses constitutive PrP expression by skeletal muscle and is the first to test PrP effects on muscle function. Our data identify similarities in isoform expression and glycosylation pattern of PrP between human and murine muscles. Functional studies show that PrP is an essential modulator of redox homeostasis, muscle mass, and force production.

PrP expression in muscle

Basic properties of PrP expression are similar between human and murine muscle. At the mRNA level, we identified three PRNP splice variants in human diaphragm. The most prevalent isoform, hPRNP002, has strong sequence identity with the sole murine isoform. Immunoblot analyses reinforce basic similarities at the protein level. PrP protein from human diaphragm and most murine limb muscles is heavily glycosylated. PrP also shows a similar gel migration pattern between species, for example, ∼36 vs. ∼35 kD for human and mouse diglycoforms, respectively. Among mouse muscles, variations in total PrP content are modest, differing less than 50% between gastrocnemius (highest content) and diaphragm (lowest).

In contrast, PrP glycosylation patterns are highly divergent. Human PrP has two potential N-glycosylation sites, Asn181IleThr and Asn197PheThr, located in the helix-loop-helix motif at the C-terminus (39). Both sites are glycosylated in most PrP of human diaphragm, whereas the diglycoform is less prevalent in murine diaphragm, an apparent interspecies difference. PrP glycosylation patterns also vary among mouse muscles. The differences we observed between tibialis anterior and soleus are similar to those reported by Massimino and colleagues (24). The congruence of their data from CD-1 mice with our data from FVB/N mice suggests that PrP expression patterns are not strain specific.

Massimino et al. (24) noted that PrP glycosylation was greater in tibialis anterior than in soleus, the latter being a slower limb muscle. Our data suggest glycosylation is not tightly linked to contraction speed per se. For example, gastrocnemius (most glycosylation) and diaphragm (least) have similar contractile properties. An alternative interpretation is that metabolic characteristics influence PrP glycosylation. We measure more PrP glycosylation in primarily glycolytic muscles (gastrocnemius, EDL, tibialis anterior) than aerobic muscles (soleus, diaphragm). This dichotomy may relate to higher mitochondrial content in aerobic muscle and higher rates of ROS production, since oxidant activity opposes synthesis of the glycosylated isoforms (6).

PrP and redox homeostasis

PrP plays an antioxidant role in neural cells (41) that is consistent with PrP chelation of copper, iron, and manganese ions (8, 16, 43). In myotubes and diaphragm muscle fibers, we found that PrP deficiency elevates cytoplasmic oxidant activity as measured by DCFH fluorescence, an assay that detects both reactive oxygen species (ROS) and NO derivatives (28). Follow-up studies using an NO-selective assay detected no changes in NO activity of PrP-deficient muscle fibers or myotubes. These findings suggest that PrP opposes oxidant activity in muscle via an NO-independent mechanism, likely by buffering ROS or slowing ROS production. Although the mechanisms by which PrP modulates redox balance were beyond the scope of the current study, potential mechanisms include the capacity of PrP to bind transition metal ions. Nishimura et al. (32) found PrP-deficient cells were more susceptible to copper-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis, suggesting PrP may inhibit Fenton reactions by binding copper. Alternatively, PrP is proposed to modulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes. Previous work has shown reduced SOD1 activity in PrP deficient mice (20).

PrP and muscle force

Behavioral studies show that PrP-deficient mice have reduced exercise capacity (30, 31) and motor behavioral deficits (29). This observation might be explained by altered neural activity (e.g., changes in motivation or coordination), cardiopulmonary insufficiency, or loss of muscle function. Our data confirm a role for the latter mechanism. PrP deficiency depresses absolute force of adult murine diaphragm by ∼40%.

Weakness of PrP-deficient muscle was caused by parallel decrements in contractile function and muscle size. Contractile dysfunction is evident in specific force (force/unit area), which was depressed at most stimulation frequencies. The concurrent elevation of oxidant activity is a likely cause of dysfunction as occurs in sepsis (46), mechanical unloading (25), and exposure to inflammatory mediators (10, 17). Force was further lessened by the diminished size of PrP-deficient fiber bundles. Smaller fiber bundles are consistent with lower body weights and smaller EDL muscles in PrP-deficient mice. Decrements in muscle mass may reflect activation of the ubiqutin–proteasome pathway. EDL contained higher levels of atrogin-1/MAFbx, a ubiquitin ligase that mediates muscle atrophy (12) and is upregulated by oxidative stimuli (22). Alternatively, Stella et al. (45) have shown that PrP promotes regeneration of adult muscle. Thus a deficiency in regeneration could result in reduced muscle mass with age.

This project did not examine the infectious PrPSc form, and PrPSc contributions to muscle pathology are largely unstudied. However, prion diseases are commonly associated with oxidative stress (34), muscle wasting (1), and weakness (2). These characteristics may be related. PrPSc accumulation in skeletal muscle is predicted to disrupt redox control and promote oxidative stress. The latter can stimulate protein catabolism (27), apoptosis (3), and contractile dysfunction (36), leading to muscle atrophy and weakness. Opposing this model, PrPSc levels in muscle are much lower than in the central nervous system, even in the late stages of prion disease. At present, it is not clear whether PrPSc accumulation is sufficient to compromise muscle in prion disease.

PrP and insulin-dependent glucose transport

Previous work has shown altered glycosylation of the insulin receptor in scrapie-infected cells (33). This suggests PrP may affect the efficiency of insulin signaling. However, we compared insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle of PrP-deficient and wild-type mice and detected no difference.

Temporal changes in PrP expression

PrP expression and functional importance appear to increase with age in muscle, as observed in other tissues (11). The protein levels of all three glycoforms increase progressively during myotube differentiation and maturation. In adolescent mice, PrP is less prevalent than in adult muscle and its absence has no effect on the functional properties we measured. In adult mice, muscle PrP levels are higher and functional importance is more clear. Genetic deficiency decreases body weight of adult mice, stimulates oxidant activity in muscle fibers, depresses absolute and specific forces, and diminishes size of some muscles. Interestingly, the age-related increase in PrP content is smaller in soleus than EDL (1- vs. 4-fold) and adult soleus weight is unaffected by PrP deficiency (data not shown). These findings suggest PrP expression and functional importance are both age- and muscle-specific in mice.

We detected no effect of age on PrP mRNA or protein levels in human diaphragm. However, this outcome should be interpreted cautiously. Our biopsy donors spanned a limited range and included no adolescents. Also, cause of death was widely divergent among our donors. Many older individuals died of chronic diseases that may have affected PrP expression.

Cell culture model

The C2C12 cell line appears to be a useful model for studying PrP biology. PrP expression increases with differentiation of C2C12 myotubes, as occurs in primary muscle cell culture (24). PrP expression can be suppressed by morpholino during differentiation without disrupting myotube formation. Also, where tested, the cellular responses to PrP knockdown were consistent between myotubes and adult mouse muscle.

Conclusion

This study provides the first direct assessment of PrP effects on skeletal muscle function. We found that PrP expression varies by species, among muscles, and with age. PrP deficiency increases cellular oxidant activity, depresses force, and promotes muscle atrophy. We conclude that basic research is needed to define PrP-dependent signaling events and their cellular target(s) in muscle. In parallel, PrP effects on muscle function suggest potential roles in physiologic adaptation (e.g., to exercise training or mechanical unloading), and disease-related weakness that warrant investigation.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue

Our protocol for the acquisition and use of human tissue was approved in advance by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (protocol #04-0206-P3B). Diaphragm muscle tissue was obtained from the Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders (Baltimore, MD). The samples were from nine deceased male individuals. Age at death ranged from 20–61 years; postmortem intervals ranged from 6–24 hours (14.8±6.3, mean±SD), causes of death include motor vehicle accidents (5 subjects, ages 20–43 years), carbon monoxide poisoning (1 subject, age 44 years), and unknown causes linked to arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (3 subjects, ages 57–61 years). Samples were stored at −80°C until processed for analysis.

Animal use

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky Medical Center (protocols #01031M2006 and #2007-0240) and were conducted in strict accordance with the Public Health Service animal welfare policy. FVB/N mice (25–34 g; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) and transgenic mice were housed in polycarbonate cages using a 12-h on/12-h off lighting schedule. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation after induction of deep anesthesia by isoflurane (Aerrane, Baxter Healthcare Corp, Deerfield, IL).

Transgenic mice

PrP-deficient mice (Zurich I strain), originally maintained on a mixed 129/Sv - C57BL/6 background were crossed with wild-type FVB animals to produce FVB/PrP0/0 mice (23). An inbred colony was established and maintained at the University of Kentucky from breeding pairs obtained from Stanley Prusiner by way of George Carlson (McLaughlin Research Institute, Great Falls, Montana). Transgenic mice engineered to overexpress full-length murine PrP on an FVB/Prnp0/0 background (i.e., Tg(MoPrP)4112 mice), were generated by methods described elsewhere (26).

Cell culture

C2C12 myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were seeded at a density of 8,000–10,000 cells/cm2 and allowed to proliferate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 1.6 g/L sodium bicarbonate supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml PenStrep (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 2 days, myoblast cultures were shifted to medium lacking FBS and supplemented with 2% horse serum. Cultures were allowed to differentiate for 5–6 days, replacing medium every 48 h. Prion was knocked down in cultured myotubes by use of a mouse PRNP001-specific morpholino (5′-GCAGCCAGTAGCCAAGGTTCGCAT-3′, Gene Tools, Philomath, OR). Morpholino (5 μM) was added to the cell culture medium followed by addition of Endo-Porter (6 μM, Gene Tools) delivery reagent. Control cell cultures received Endo-Porter, alone. Knockdown was assessed and assays were performed 48 hrs after morpholino delivery.

PrP mRNA measurements

Total RNA was extracted from human diaphragm samples and converted to cDNA in one-microgram aliquots with random hexamers and reverse transcriptase (SuperScriptIII, Invitrogen), as we described elsewhere (50). Human PrP gene (PRNP) consists of two exons with the second exon encompassing the complete PrP coding sequence; the mouse PrP gene (Prnp) consists of three exons, with the third exon encompassing the complete PrP coding sequence. In PRNP, two alternative first exons have been reported, and the exact splice site at the exon 1–2 junction shows subtle variation, leading to multiple possible isoforms with five consensus-coding sequences (CCDS) (www.ENSEMBL.org, release 58; last accessed June 30, 2010). To quantify PrP expression by real-time PCR, we designed PCR sense primers specific to each exon 1. These primers were compatible with a common antisense primer in exon 2. Hence, the 5′ sense primer CGAGCTTCTCCTCTCCTCAC within exon 1A and 3′ antisense primer AGAGGCCCAGGTCACTCC within exon 2 were predicted to amplify fragments of CCDS prion isoforms corresponding to hPRNP002 (105 bp PCR product), hPRNP003 (101 bp product), hPRNP202 (100 bp), and hPRNP205 (96 bp). A 5′ sense primer within exon 1B, GTCTCCGCTCGGGTGAG, and the same AGAGGCCCAGGTCACTCC exon 2 antisense primer were predicted to produce a 113 bp cDNA corresponding to hPRNP201. In Prnp, only one coding transcript is reported. Mouse primers, 5′ sense TGATTGAAGGCAACAGGAAAAA and 3′ antisense GGGAATGAACAAAGGTTTGCTT were used to amplify a 72 bp product specific for exon 3 of mPRNP001. Amplification reactions were 1 μM with respect to each primer, 1x SYBR-green Master Mix (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and the equivalent of 20 ng of template cDNA. PCR profiles consisted of a 2-min pre-incubation period at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s (Chromo4, BioRad, Hercules, CA). Primer specificity was ensured by separating the PCR products via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and SYBR-gold staining, as well as melting curves at the completion of real-time PCR. To unequivocally identify the PCR products, they were gel-purified, cloned into pcDNA2.1 (TOPO-TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen), and individual clones were sequenced (Davis Sequencing, Inc., Davis, CA). For quantification, each cDNA sample was amplified three times using duplicate reactions. Samples were compared to standard curves generated with purified and quantified PCR product. The copy numbers of the prion isoforms were normalized to the mean of the copy numbers of 18s rRNA, which were quantified similarly (sense primer CTGAGAAACGGCTACCACATC, antisense primer CGCTCCCAAGATCCAACTAC 255 bp PCR product size).

Muscle force measurements

Muscle fiber bundles were isolated from the costal diaphragm and mounted in a temperature-controlled bath containing Krebs-Ringer solution (in mM: 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2) bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 at room temperature. Silk suture (6-0) was used to fix the tendon to a force transducer (BG Series 100g, Kulite, Leonia, NJ) mounted on a micrometer by which muscle length was adjusted. The muscle was positioned between platinum wire stimulating electrodes and stimulated to contract isometrically using electrical field stimulation (supramaximal voltage, 1.2 ms pulse duration). The output of the force transducer was recorded using an oscilloscope (546601B; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) and a chart recorder (BD-11E; Kipp and Zonen, Delft, The Netherlands). In each experiment, muscle length was adjusted to optimize twitch force (optimal length, Lo). The bath temperature was then increased to 37°C and 30 min were allowed for thermoequilibration. The force-frequency relationship was determined by stimulating muscle contractions every 2 min at frequencies of 1 to 300 Hz with a tetanic train duration of 500 ms. Maximal tetanic contractions (300 Hz) were stimulated between lower-frequency contractions to monitor contractile stability. After the force-frequency protocol, fatigue was assessed using tetanic contractions every 2 s for 600 s (stimulus frequency 30 to 40 Hz, train duration 500 ms, pulse duration 0.3 ms). Following each experiment, Lo was measured using an electronic caliper (CD-6" CS, Mitutoyo America Corp, Aurora, IL) and the muscle was removed, blotted dry, and weighed. Cross-sectional area was determined as defined by Close (9).

Total protein and Western blot analyses

After treatment, myotubes were washed with PBS and scraped from the surface or muscle samples were homogenized by hand in 20 volumes of 20 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.5, 2% SDS. The lysates were sonicated on ice and then heated at 98°C for 5 min. For deglycosylation, 1.5 volumes of PBS/2% NP-40 containing 500 U/ml PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) were added and samples were incubated for 20 h at 37°C. Five volumes of 6X protein loading buffer (300 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 600 mM DTT, 60% glycerol, 12% SDS, 0.006% Bromphenol blue) were added and equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane of 4%–15% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed at 200 V for 50 min. Proteins were transferred to nylon membranes at 200 mA, 2 h for Western blot. Membranes were blocked (Odyssey blocking buffer; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies [anti-PrP (6D11), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; anti-atrogin-1/MAFbx, ECM Biosciences, Versailles, KY] overnight in blocking buffer and an equal volume PBS plus 0.1% Tween (PBST), followed by four 5 min washes in PBST. Membranes were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit IRD 800, Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) in blocking buffer/PBST plus 0.01% SDS for 45 min, followed by four 5 min washes. The membrane was dried and blots were imaged by use of an infrared scanner (Odyssey Infrared Imaging System, LI-COR) to quantify differences. Integrated intensity values were normalized for total protein measured by use of Simply Blue (Invitrogen).

Cytosolic oxidant activity

The fluorochrome probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (H2DCF-DA; Invitrogen) was used to measure oxidant activity (38). Murine hemidiaphragms or mature C2C12 myotubes were loaded with 20 μM DCFH-DA (10 μM for myotubes) for 60 or 30 min, respectively. Accumulation of the oxidized derivative (DCF; 480 nm excitation, 520 nm emission) was measured by use of an epifluorescence microscope (TE2000-S; Nikon Instruments) with CCD camera (CoolSnap ES; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and a computer-controlled shutter (Lambda 10-B; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) in the excitation light pathway. DCF emissions were acquired by 10 ms exposure (20 ms for myotubes) to excitation light (480 nm); emission intensities were measured using commercial data acquisition and analysis software (Metamorph; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Final values for DCF emissions were corrected for photo-oxidation artifact by measuring fluorescence in two images captured in rapid succession and subtracting the increase from the first to the second image from the initial image value. The nitric oxide (NO) specific probe 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (DAF-FM-DA, Invitrogen) was used to measure NO activity in the cytoplasm. Murine hemidiaphragms or C2C12 myotubes were loaded with 5 μM DAF-FM for 60 or 30 min respectively, imaged, and emission intensity was measured as above. No photo-oxidation correction was necessary.

Histological preparation

Murine diaphragm was embedded in O.C.T. Compound (Sakura, Dublin, OH) and frozen in 2-methyl-butane (Sigma) cooled on dry ice. Six-micron slices were fixed in 2% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Slices were rinsed in PBS, blocked for 1 h in 5% donkey serum in PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100. Slices were incubated with antibody to neuronal-type NO synthase (anti-nNOS 1:100; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) in PBS+0.3% Triton overnight at 4°C, rinsed in PBS, and incubated with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa488 (1:200, Molecular Probes) in PBS+0.3% Triton for 1 h at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS, slices were covered with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) and imaged using a Leica SP1 inverted confocal microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

Glucose uptake

To measure 2-deoxy-D[1,2-3H]glucose uptake, paired EDL muscles were isolated from each mouse and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in Krebs bicarbonate buffer (117 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, and 24.6 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.5) containing 2 mM pyruvate and equilibrated with 95% O2, 5% CO2. Muscle length was maintained at approximately optimal length (Lo). After 50 min, the buffer was drained and new buffer plus 1 mM 3H-glucose (1.5 μCi/ml 2-deoxy-D-[1,2-3H] glucose; Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA)/7 mM 14C-mannitol (0.45 μCi/ml D-[1-14C]mannitol; Perkin Elmer) was added to the organ baths at 37°C. When drugs were administered, they were present during all incubations. After 10 min, muscles were immersed in buffer containing no sugars, blotted, cut from threads, and frozen in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube at −80°C. Frozen muscles were weighed and transferred to another microcentrifuge tube for digestion in 250 μl of 1N NaOH. Samples were heated at 80°C for ∼ 10 min, vortexed, centrifuged, and 250 μl of 1 N HCl was added to neutralize the NaOH. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged again and 350 μl was pipetted to a minivial containing 4 ml scintillation cocktail. Radioactivity was determined overnight in a scintillation counter set up for dual label dpm. Transport rates for each sample were determined by dpm counts for all samples including blanks.

Statistical analyses

Western blot data were compared by t-test or ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test as appropriate. Differences between force-frequency curves were analyzed using two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey tests. Comparisons of DCFH and DAF-FM data were evaluated using paired t-tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using commercial software (SigmaStat, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Abbreviations Used

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPSc

scrapie (infectious prion protein)

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD1

CuZn superoxide dismutase

- TA

tibialis anterior

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants #AR055974 to MBR, #1P01AI077774-015261 to GCT, #AG026147 to SE), American Heart Association (research fellowship to MAC), and University of Kentucky Center for Muscle Biology. The authors thank Laura Gilliam and Leonardo Ferreira for scientific and editorial contributions.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Angers RC. Browning SR. Seward TS. Sigurdson CJ. Miller MW. Hoover EA. Telling GC. Prions in skeletal muscles of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science. 2006;311:1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1122864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arata H. Takashima H. Hirano R. Tomimitsu H. Machigashira K. Izumi K. Kikuno M. Ng AR. Umehara F. Arisato T. Ohkubo R. Nakabeppu Y. Nakajo M. Osame M. Arimura K. Early clinical signs and imaging findings in Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome (Pro102Leu) Neurology. 2006;66:1672–1678. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218211.85675.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga M. Sinha Hikim AP. Datta S. Ferrini MG. Brown D. Kovacheva EL. Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Sinha-Hikim I. Involvement of oxidative stress and caspase 2-mediated intrinsic pathway signaling in age-related increase in muscle cell apoptosis in mice. Apoptosis. 2008;13:822–832. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DR. Nicholas RS. Canevari L. Lack of prion protein expression results in a neuronal phenotype sensitive to stress. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:211–224. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown DR. Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. Schmidt B. Kretzschmar HA. Prion protein-deficient cells show altered response to oxidative stress due to decreased SOD-1 activity. Exp Neurol. 1997;146:104–112. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capellari S. Zaidi SI. Urig CB. Perry G. Smith MA. Petersen RB. Prion protein glycosylation is sensitive to redox change. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34846–34850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers MA. Moylan JS. Smith JD. Goodyear LJ. Reid MB. Stretch-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle is mediated by reactive oxygen species and p38 MAP-kinase. J Physiol. 2009;587:3363–3373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi CJ. Anantharam V. Saetveit NJ. Houk RS. Kanthasamy A. Kanthasamy AG. Normal cellular prion protein protects against manganese-induced oxidative stress and apoptotic cell death. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:495–509. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Close RI. The relations between sarcomere length and characteristics of isometric twitch contractions of frog sartorius muscle. J Physiol. 1972;220:745–762. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira LF. Moylan JS. Gilliam LA. Smith JD. Nikolova-Karakashian M. Reid MB. Sphingomyelinase stimulates oxidant signaling to weaken skeletal muscle and promote fatigue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C552–560. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00065.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh AX. Li C. Sy MS. Wong BS. Altered prion protein glycosylation in the aging mouse brain. J Neurochem. 2007;100:841–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes MD. Lecker SH. Jagoe RT. Navon A. Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14440–14445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graner E. Mercadante AF. Zanata SM. Martins VR. Jay DG. Brentani RR. Laminin-induced PC-12 cell differentiation is inhibited following laser inactivation of cellular prion protein. FEBS Lett. 2000;482:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillot-Sestier MV. Sunyach C. Druon C. Scarzello S. Checler F. The alpha-secretase-derived N-terminal product of cellular prion, N1, displays neuroprotective function in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35973–35986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.051086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haigh CL. Brown DR. Prion protein reduces both oxidative and non-oxidative copper toxicity. J Neurochem. 2006;98:677–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haigh CL. Lewis VA. Vella LJ. Masters CL. Hill AF. Lawson VA. Collins SJ. PrPC-related signal transduction is influenced by copper, membrane integrity and the alpha cleavage site. Cell Res. 2009;19:1062–1078. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardin BJ. Campbell KS. Smith JD. Arbogast S. Smith J. Moylan JS. Reid MB. TNF-alpha acts via TNFR1 and muscle-derived oxidants to depress myofibrillar force in murine skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:694–699. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00898.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiuchi M. Yamazaki N. Ikeda T. Ishiguro N. Shinagawa M. A cellular form of prion protein (PrPC) exists in many non-neuronal tissues of sheep. J Gen Virol. 1995;76(Pt 10):2583–2587. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-10-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanaani J. Prusiner SB. Diacovo J. Baekkeskov S. Legname G. Recombinant prion protein induces rapid polarization and development of synapses in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons in vitro. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1373–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klamt F. Dal-Pizzol F. Conte da Frota ML., Jr. Walz R. Andrades ME. da Silva EG. Brentani RR. Izquierdo I. Fonseca Moreira JC. Imbalance of antioxidant defense in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawler JM. Powers SK. Oxidative stress, antioxidant status, and the contracting diaphragm. Can J Appl Physiol. 1998;23:23–55. doi: 10.1139/h98-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YP. Chen Y. Li AS. Reid MB. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates ubiquitin-conjugating activity and expression of genes for specific E2 and E3 proteins in skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C806–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lledo PM. Tremblay P. DeArmond SJ. Prusiner SB. Nicoll RA. Mice deficient for prion protein exhibit normal neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2403–2407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Massimino ML. Ferrari J. Sorgato MC. Bertoli A. Heterogeneous PrPC metabolism in skeletal muscle cells. FEBS Letters. 2006;580:878–884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matuszczak Y. Arbogast S. Reid MB. Allopurinol mitigates muscle contractile dysfunction caused by hindlimb unloading in mice. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75:581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mays CE. Titlow W. Seward T. Telling GC. Ryou C. Enhancement of protein misfolding cyclic amplification by using concentrated cellular prion protein source. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moylan JS. Reid MB. Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:411–429. doi: 10.1002/mus.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murrant CL. Andrade FH. Reid MB. Exogenous reactive oxygen and nitric oxide alter intracellular oxidant status of skeletal muscle fibres. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;166:111–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazor KE. Seward T. Telling GC. Motor behavioral and neuropathological deficits in mice deficient for normal prion protein expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nico PB. de-Paris F. Vinade ER. Amaral OB. Rockenbach I. Soares BL. Guarnieri R. Wichert-Ana L. Calvo F. Walz R. Izquierdo I. Sakamoto AC. Brentani R. Martins VR. Bianchin MM. Altered behavioural response to acute stress in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nico PB. Lobao-Soares B. Landemberger MC. Marques W., Jr. Tasca CI. de Mello CF. Walz R. Carlotti CG., Jr. Brentani RR. Sakamoto AC. Bianchin MM. Impaired exercise capacity, but unaltered mitochondrial respiration in skeletal or cardiac muscle of mice lacking cellular prion protein. Neurosci Lett. 2005;388:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura T. Sakudo A. Nakamura I. Lee DC. Taniuchi Y. Saeki K. Matsumoto Y. Ogawa M. Sakaguchi S. Itohara S. Onodera T. Cellular prion protein regulates intracellular hydrogen peroxide level and prevents copper-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostlund P. Lindegren H. Pettersson C. Bedecs K. Altered insulin receptor processing and function in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cell lines. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;97:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pamplona R. Naudi A. Gavin R. Pastrana MA. Sajnani G. Ilieva EV. Del Rio JA. Portero-Otin M. Ferrer I. Requena JR. Increased oxidation, glycoxidation, and lipoxidation of brain proteins in prion disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pankiewicz J. Prelli F. Sy MS. Kascsak RJ. Kascsak RB. Spinner DS. Carp RI. Meeker HC. Sadowski M. Wisniewski T. Clearance and prevention of prion infection in cell culture by anti-PrP antibodies. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2635–2647. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powers SK. Jackson MJ. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1243–1276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reid MB. Nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and skeletal muscle contraction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:371–376. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reid MB. Haack KE. Franchek KM. Valberg PA. Kobzik L. West MS. Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. I. Intracellular oxidant kinetics and fatigue in vitro. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1797–1804. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudd PM. Wormald MR. Wing DR. Prusiner SB. Dwek RA. Prion glycoprotein: structure, dynamics, and roles for the sugars. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3759–3766. doi: 10.1021/bi002625f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandstrom ME. Zhang SJ. Bruton J. Silva JP. Reid MB. Westerblad H. Katz A. Role of reactive oxygen species in contraction-mediated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2006;575:251–262. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider B. Mutel V. Pietri M. Ermonval M. Mouillet-Richard S. Kellermann O. NADPH oxidase and extracellular regulated kinases 1/2 are targets of prion protein signaling in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13326–13331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235648100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silberstein L. Webster SG. Travis M. Blau HM. Developmental progression of myosin gene expression in cultured muscle cells. Cell. 1986;46:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh A. Kong Q. Luo X. Petersen RB. Meyerson H. Singh N. Prion protein (PrP) knock-out mice show altered iron metabolism: A functional role for PrP in iron uptake and transport. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steele AD. Emsley JG. Ozdinler PH. Lindquist S. Macklis JD. Prion protein (PrPc) positively regulates neural precursor proliferation during developmental and adult mammalian neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3416–3421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511290103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stella R. Massimino ML. Sandri M. Sorgato MC. Bertoli A. Cellular prion protein promotes regeneration of adult muscle tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4864–4876. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Supinski G. Stofan D. Callahan LA. Nethery D. Nosek TM. DiMarco A. Peroxynitrite induces contractile dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:783–791. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Telling GC. Haga T. Torchia M. Tremblay P. DeArmond SJ. Prusiner SB. Interactions between wild-type and mutant prion proteins modulate neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westaway D. Cooper C. Turner S. Da Costa M. Carlson GA. Prusiner SB. Structure and polymorphism of the mouse prion protein gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6418–6422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong BS. Liu T. Li R. Pan T. Petersen RB. Smith MA. Gambetti P. Perry G. Manson JC. Brown DR. Sy MS. Increased levels of oxidative stress markers detected in the brains of mice devoid of prion protein. J Neurochem. 2001;76:565–572. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu H. Tucker HM. Grear KE. Simpson JF. Manning AK. Cupples LA. Estus S. A common polymorphism decreases low-density lipoprotein receptor exon 12 splicing efficiency and associates with increased cholesterol. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1765–1772. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]