Abstract

Clarkson’s syndrome, also called idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome is a rare condition characterised by vascular hyper permeability resulting in extreme intravascular volume depletion. The syndrome is unique and almost paradoxical in its presentation, with findings initially suggesting overwhelming heart failure, but in reality the extra vascular fluid represents overt capillary leak, with ultimate intravascular volume depletion, a low output state and hypovolemic shock. Previously described characteristics have classically included severe oedema and anasarca with rapid, profound shock, typically accompanied by haemoconcentration. The authors describe a patient, initially seeming benign in presentation, who rapidly progressed with confusing findings of fluid overload by examination and imaging, ultimately manifesting these findings by severe capillary leak rather than hydrostatic oedema, with ultimate hypovolaemic shock, multisystem organ failure and death. Our aim is that by describing clinical, haemodynamic and pathologic descriptors of the disease, the authors can aid in increasing physician awareness of this unusual syndrome.

Background

Clarkson’s syndrome was first described by Clarkson et al in 1960.1 Subsequent reports have described considerable variability in course, treatment and outcome.2 Its peculiar presentation often leads to misdiagnosis; hence, its incidence may be underestimated. Clinical features mimic heart failure at the outset; the paradox is that these findings ultimately do not represent hydrostatic forces, but rather extreme capillary leak, leading ultimately to a hypovolemic shock state.

The syndrome is rare, and its pathophysiology is poorly understood. It is deemed to be reversible in majority of cases with recurrent attacks and mortality as high as 76% during an acute episode.3 With increasing awareness, acute and chronic forms have been recognised more frequently and recently a familial variant has also been described.4

Case presentation

A previously healthy 80-year-old man presented 3 weeks ago to a community hospital with complaints of fullness in his pelvis and rectum. He had hypothyroidism and no other chronic or acute illness, and prided himself by walking 2 miles daily as his usual routine.

Investigation showed normal comprehensive metabolic profile and complete blood count barring monocytosis. An abdominal CT scan showed ascites and inflammatory change of mesentery, thickening of a segment of colon, evidence of colonic diverticulosis with no diverticulitis and minimal pleural and pericardial effusion. Interval imaging after 4 days revealed improved appearances.

Patient was discharged on day 4 with resolution of symptoms with instructions to complete 10 days course of oral metronidazole and ciprofloxacin.

After discharge, patient noticed progressively increasing abdominal and limb swelling and was prescribed lasix by his primary care physician. Despite this, he rapidly worsened over 4 days, now with dyspnoea, orthopnoea, abdominal fullness, oedema and a rapid weight gain of 15 lbs, the patient presented to the same community hospital. Preliminary evaluation showed pericardial effusion and overt shock and was henceforth transferred to our tertiary center.

On initial evaluation at our center, he was tachypnoeic, and hypotensive. There was obvious fluid overload marked by oedema to the thighs with grade 3 bilateral pitting pedal oedema. Chest examination revealed reduced breath sounds at the bases with egophany and dullness to percussion, the heart sounds were distant heart tones without a murmur or gallop. Liver was difficult to palpate due to tense abdominal fluid and shifting dullness.

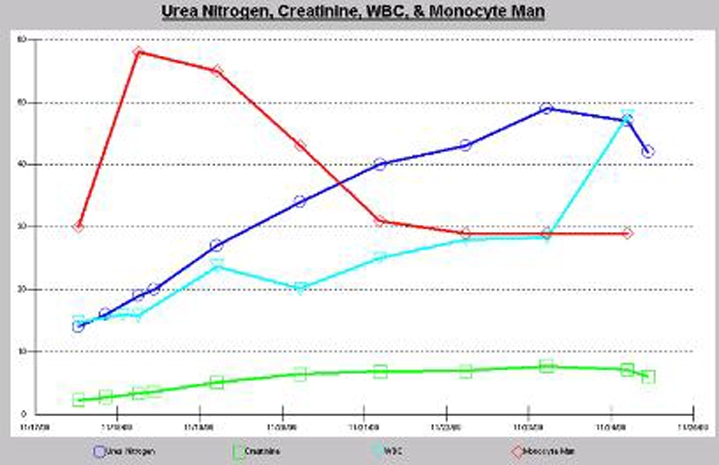

Relevant blood tests on admission are listed in table 1. Subsequent relevant trend of bloods is shown in figure 1. Figure 2 shows echocardiogram revealing significant pericardial effusion with haemodynamic compromise.

Table 1.

Relevant blood tests on admission.

| Test | Result | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| White cell count | 14.8 | 4–10.8×10^9/l |

| Absolute neutrophils | 6.30 | 1.8–7.8×10^9/l |

| Absolute monocytes | 8.82 | 0.0–0.90×10^9/l |

| Haemoglobin | 10.9 | 14–18 g/dl |

| Haematocrit | 33 | 42–52% |

| ESR | 7 | 0–20 mm/h |

| C-reactive protein | 148 | 0–9.9 mg/dl |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 14 | 8–20 mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 2.27 | 0.6–1.30 mg/dl |

| AST/ALT | 19/22 | 10–40 IU/l |

| Total protein/Albumin | 4.5/2.2 | 6–8/3.5–5 g/l |

| Electrolytes | Normal | |

| TSH | 14 | 0.3–5.0 mcu/ml |

| BNP | 236 | 0–99 pg/ml |

| ANA, ANCA, CEA, complements, cortisol | Normal |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Figure 1.

Subsequent relevant trend of bloods.

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram revealing significant pericardial effusion with haemodynamic compromise.

An emergent echocardiography performed revealed pericardial effusion with haemodynamic compromise, this was drained percutaneously. The pericardial fluid was not diagnostic.

His symptoms progressed with perpetual shock, rapidly worsening oedema leading to anasarca. Inotropic support with monitored low central venous pressures failed to improve clinical condition. Serial echocardiograms were done, revealing a reaccumulating pericardial effusion requiring a pericardial drain. Despite significant pericardial effusion, a right heart catheter study revealed low central pressures with capillary wedge pressure of eight; reflecting reduced vascular volume from capillary leak.

Monocytosis was considered to be reactive and further investigations were not done with recommendation from haematology. Nephrology services were sort for overt renal failure with eventual anuria requiring haemofiltration.

Diagnosis remained a mystery until late in course of the disease. Despite aggressive medical management, he succumbed to complications of this condition. He ultimately died of hypovolemic shock. Autopsy features supported the diagnosis of Clarkson’s syndrome.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis included congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock that was refractory to conventional aggressive medical treatment. Hypothyroid cardiomyopathy was considered as possible aetiology as thyroid stimulating hormone was markedly raised; however, increased thyroxine dosage early in course of illness did not lead to any clinical improvement. Nephrotic syndrome was not supported by minimal urinary protein loss. Patient did not have any long history of bowel abnormalities to support protein losing enteropathy.

Outcome and follow-up

This patient presented with all the misgivings manifesting as heart failure, but ultimately representing extraordinary capillary leak and hypovolemic shock with multisystem organ failure unresponsive to aggressive treatment. Autopsy findings supported the diagnosis of idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS).

Discussion

Clarkson’s syndrome is also called ISCLS. The hallmark feature of Clarkson’s syndrome is vascular hyper permeability, with resultant extravascular extravasation. It is a diagnosis of exclusion after other causes of increased vascular permeability like sepsis, burns and drug reactions have been excluded.

Although the pathophysiology is not completely understood, two phases of the disease have been identified. In the leak phase, it is postulated that up to 70% of the plasma shifts from intravascular space to the interstitial space, leading to hypovolemic shock and related complications. The recovery phase is characterised by restoration of intravascular volume and diuresis. Chronic forms of this condition have also been described. And recently a familial variant has been reported.4

The most widely accepted hypothesis is that of cell apoptosis without widening of intercellular gaps rather than endothelial contraction or retraction. This is supported by induction of apoptosis of cultured microvascular endothelial cells with serum from patients with ISCLS.5 Additionally, the known modulators of capillary permeability (histamine, complements, kinins, prostaglandins and serotonin) are found to be normal.

A clinical syndrome similar to ISCLS has been reported with the use of interleukin 2 and interferon, implicating a possible role for cytokines.6 7

Monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS) is commonly associated with ISCLS, with some case series report as high incidence as 85% but its significance is uncertain. There is not been any increased risk of myeloma with MGUS in patients with ISCLS.2 8 Zhang et al purified paraproteins from three patients with SCLS and found that these antibodies did not bind to cultured endothelial cells and did not have any cytotoxicity, alone or in the presence of neutrophils, towards cultured human endothelial cells.9

Any strategy that would reduce endothelial hyper permeability may be successful in ISCLS. Terbutaline and theophylline, have immune modulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that are useful in antagonising cytokine mediated endothelial damage and capillary hyper permeability.10 Tahirkheli et al demonstrated prophylactic efficacy in eight patients followed for 9 years.11

Steroid administration may have a role in capillary leak phase, diuretic may be useful in recruitment phase.8 11 However, no study has demonstrated clear benefit. Interestingly, statins have also shown to interfere with RhoA/RHO kinase pathway and to reduce vascular leakage, speculating that they may be useful in this condition.12

Learning points.

-

▶

ICLS is poorly understood due to its rarity, and as a result may be misdiagnosed. Common differentials include distributive shock secondary to sepsis, cardiogenic shock, nephrotic syndrome and protein losing enteropathy. Characteristics have classically included severe oedema and anasarca with rapid, profound shock and typically accompanied by haemoconcentration.

-

▶

This syndrome may initially mimic overt congestive heart failure with ascites, oedema and hypotension, but can be differentiated with low central pressures on cardiac catheter study. The diagnosis requires clinical suspicion and confirmation of low intra vascular volume status with excess third spacing would support such a diagnosis.

-

▶

The mortality is reported as high as 76 per cent during an acute presentation of this syndrome. Awareness of such a syndrome would aid physicians to recognise this condition early, direct therapy appropriately and perhaps alter the outcome.

-

▶

Treatment is mainly supportive. Agents such as terbutaline and theophylline that in theory reduce vascular permeability; have shown some benefit in patients with recurrent episodes.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Clarkson B, Thompson D, Horwith M, et al. Cyclical edema and shock due to increased capillary permeability. Am J Med 1960;29:193–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druey KM, Greipp PR. Narrative review: the systemic capillary leak syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:90–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teelucksingh S, Padfield PL, Edwards CR. Systemic capillary leak syndrome. Q J Med 1990;75:515–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sion-Sarid R, Lerman-Sagie T, Blumkin L, et al. Neurologic involvement in a child with systemic capillary leak syndrome. Pediatrics 2010;125:e687–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assaly R, Olson D, Hammersley J, et al. Initial evidence of endothelial cell apoptosis as a mechanism of systemic capillary leak syndrome. Chest 2001;120:1301–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenstein M, Ettinghausen SE, Rosenberg SA. Extravasation of intravascular fluid mediated by the systemic administration of recombinant interleukin 2. J Immunol 1986;137:1735–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigneau C, Haymann JP, Khoury N, et al. An unusual evolution of the systemic capillary leak syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:492–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amoura Z, Papo T, Ninet J, et al. Systemic capillary leak syndrome: report on 13 patients with special focus on course and treatment. Am J Med 1997;103:514–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Ewan PW, Lachmann PJ. The paraproteins in systemic capillary leak syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;93:424–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vassallo R, Lipsky JJ. Theophylline: recent advances in the understanding of its mode of action and uses in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73:346–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tahirkheli NK, Greipp PR. Treatment of the systemic capillary leak syndrome with terbutaline and theophylline. A case series. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:905–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW. Targets for pharmacological intervention of endothelial hyperpermeability and barrier function. Vascul Pharmacol 2002;39:257–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]