Abstract

Dr0930, a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily in Deinococcus radiodurans, was cloned, expressed and purified to homogeneity. The enzyme crystallized in the space group P3121 and the structure was determined to a resolution of 2.1 Å. The protein folds as a (β/α)7β-barrel and a binuclear metal center is found at the C-terminal end of the β-barrel. The purified protein contains a mixture of zinc and iron and is intensely purple at high concentrations. The purple color was determined to be due to a charge transfer complex between iron in the β-metal position and Tyr-97. Mutation of Tyr-97 to phenylalanine or complexation of the metal center with manganese abolished the absorbance in the visible region of the spectrum. Computational docking was used to predict potential substrates for this previously unannotated protein. The enzyme was found to catalyze the hydrolysis of δ- and γ-lactones with an alkyl substitution at the carbon adjacent to the ring oxygen. The best substrate was δ-nonanoic lactone with a kcat/Km of 1.6 × 106 M−1 s−1. Dr0930 was also found to catalyze the very slow hydrolysis of paraoxon with values of kcat and kcat/Km of 0.07 min−1 and 0.8 M−1 s−1, respectively. The amino acid sequence identity to the phosphotriesterase (PTE) from Pseudomonas diminuta is ~30%. The eight substrate specificity loops were transplanted from PTE to Dr0930 but no phosphotriesterase activity could be detected in the chimeric PTE-Dr0930 hybrid. Mutation of Phe-26 and Cys-72 in Dr0930 to residues found in the active site of PTE enhanced the kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of paraoxon. The F26G/C72I mutant catalyzed the hydrolysis of paraoxon with a kcat of 1.14 min−1, an increase of 16-fold over the wild type enzyme. These results support previous proposals that phosphotriesterase activity evolved from an ancestral parent enzyme possessing lactonase activity.

The amidohydrolase superfamily (AHS1) of enzymes has been shown to catalyze the hydrolysis of a broad spectrum of amide and ester bonds within carboxylate and phosphate substrates (1). In addition to hydrolytic reactions, members of the AHS have also been shown to catalyze decarboxylation and isomerization reactions (2, 3). All members of the AHS possess a distorted (β/α)8-barrel structural fold and an active site at the C-terminal end of the central β-barrel with a mono- or binuclear metal center (1). The metal center functions to activate solvent water for nucleophilic attack and to stabilize the tetrahedral or trigonal bipyramidal transition state (1). The AHS was first identified by Sander and Holm who recognized the structural similarities among adenosine deaminase, urease, and phosphotriesterase (PTE) (4). Since the initial discovery in 1997 more than 30 different reactions have been shown to be catalyzed by members of the AHS in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (1, 5).

Many of the enzymes within the AHS have an unknown, uncertain, or incorrect functional annotation. It has been estimated that the total number of reactions catalyzed by members of the AHS will ultimately be greater than 100 (5). We have focused our attention on the elucidation of function for those members of the AHS whose substrate and reaction profiles are unknown. We are also interested in the establishment of the structural basis for the molecular evolution of new catalytic activities from existing protein templates. Newly identified reactions catalyzed by members of the AHS include the deamination of N-formimino-l-glutamate and S-adenosyl homocysteine (6, 7). The identification of the reaction specificities for members of the AHS of unknown function can be addressed via substrate screening of compound libraries (6), genomic and operon context for bacterial enzymes (6, 8), and computational docking of potential substrates to three-dimensional structures (7, 9). Computational docking of high energy tetrahedral intermediates was effectively used in the identification of the substrate profile for Tm0936 from Thermotoga maritima (7).

The large number of reactions catalyzed by members of the AHS suggests that the active site structure perched at the C-terminal end of the β-barrel is amenable to the efficient evolution of new enzymes with modified substrate profiles. One interesting example is that of the bacterial phosphotriesterase (10). The PTE from Pseudomonas diminuta has been shown to catalyze the hydrolysis of organophosphate triesters such as the insecticide paraoxon with values of kcat/Km that approach the diffusion limit of 108 M−1 s−1 (11). The high turnover rates are unusual since organophosphate triesters are not natural products and these compounds have been introduced into the environment only since the middle of the last century. The PTE from P. diminuta has been shown to possess a weak ability to hydrolyze cyclic carboxylate esters (12). It has been suggested that the present-day PTE has evolved from an enzyme whose physiological role was the hydrolysis of lactones (12).

In this paper we have determined the structural and catalytic properties of Dr0930 from Deinococcus radiodurans. This enzyme has a sequence identity to the PTE from P. diminuta of approximately 30%. The enzyme has been crystallized and the structure determined to a resolution of 2.1 Å. Computational docking of high energy intermediates and substrate screening has been used to demonstrate that this enzyme efficiently catalyzes the hydrolysis of γ-and δ-lactones with values of kcat/Km that exceed 106 M−1 s−1. The phosphotriesterase activity is very weak but this promiscuous activity can be enhanced by over one order of magnitude with a relatively small number of changes to active site residues.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma or Aldrich. The genomic DNA from D. radiodurans R1 was purchased from ATCC. E. coli BL21(DE3) and XL1-blue cells were obtained from Stratagene. The expression vector pET-30a(+) and platinum pfx DNA polymerase were purchased from Invitrogen. The genomic DNA purification kit was obtained from Promega. Oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed by the Gene Technology Laboratory of Texas A&M University.

Cloning of Gene for Dr0930

The gene for Dr0930 from D. radiodurans was amplified from the genomic DNA using the primer pair 5’-AGAACTTCCATATGACGGCACAGACGGTGACGGGCG-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACGGAATTCTTACCCGAA CAGCCGGGCCGGGTTG-3’ (reverse). The forward primer contained an NdeI restriction site and the reverse primer introduced an EcoRI restriction site. The PCR product was gel purified, digested with NdeI and EcoRI, and cloned into the expression vector pET-30a (+) at the NdeI and EcoRI sites. The fidelity of the insert was verified by direct DNA sequencing. The mutants Y28F, Y97F, and Y98F were constructed using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. The mutants F26G, C72I, F26G/C72I, Y98F, F26G/C72I/Y97W/Y98F, G207D/R228H/L231H, and F26G/C72I/Y97W/Y98F/G207D/R228H/L231H were constructed using the method of overlap extension (13). The coding regions of all expression plasmids were completely sequenced.

Protein Purification

The plasmid containing the gene for Dr0930 was transformed into BL21(DE3) electrocompetent cells. A single colony was used to inoculate a 5 mL overnight culture of LB medium supplemented with 50 µg/mL kanamycin. The 5 mL overnight culture was then used to inoculate 1.0 L of LB medium with 50 µg/mL kanamycin. Cells were grown at 30 °C and gene expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 1.0 mM metal salt (ZnAc2, MnCl2 or CoCl2) when the OD600 of the culture reached 0.6. When MnCl2 or CoCl2 was added to the growth medium, 0.1 mM 2’2-bipyridal was added to chelate the iron in the growth medium as soon as the OD600 of the culture was approximately 0.1. The cells were harvested by centrifugation 18 hours after addition of IPTG. About 10 g of cells were obtained from 3 L of culture. For purification, 10 g of cells were resuspended in 50 mL of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and lysed by sonication (5 second pulses for 30 minutes at 0 °C) in an ice bath. After centrifugation, the nucleic acids were removed by adding 2% (w/v) protamine sulfate dropwise and then the protein was precipitated from the supernatant solution by slowly adding ground ammonium sulfate until 60% saturation. The precipitated protein from the ammonium sulfate step was resuspended in a minimum quantity of 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.5, filtered with a 0.2 µm membrane and loaded onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (Amersham Pharmacia). The fractions containing the recombinant protein were pooled based on the results from PhastGel electrophoresis. The protein solution was loaded onto a Resource Q anion exchange column (Amersham Pharmacia) and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. Dr0930 eluted from the column at approximately 150 mM NaCl. The purity of the protein was verified by SDS-PAGE.

Metal Analysis and Protein Verification

The protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using a 1 cm quartz cuvette in a SPECTRAmax-340 UV-vis or CARY 100 spectrophotometer. The extinction coefficient at 280 nm used for calculating the concentration of Dr0930 was 28 710 M−1cm−1 (14). The metal content of the purified protein was determined by inductively coupled plasma emission-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Before ICP-MS measurements, the protein samples were treated with concentrated nitric acid overnight and then diluted with distilled H2O until the final concentration of nitric acid was 1%.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Protein samples for analytical ultracentrifugation were prepared in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5. The experiments were performed using a Beckman model Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with an AN60 rotor. Sedimentation velocity experiments used a 2 channel aluminum centerpiece containing a 400 uL reference and a 380 uL sample. Preliminary sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out at six different concentrations: 26.1, 13.1, 6.5, 2.6, 1.3, and 0.64 uM. The samples were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 40,000 rpm at 25 °C. Absorbance data were collected at 280 nm for the first three concentrations and at 230 nm for the three lower concentrations. Approximately thirteen scans were collected and analyzed using Ultrascan 9.9 version for Windows (15, 16). Under these conditions, there was no dependence of sedimentation as a function of protein concentration. To determine the molecular weight of the protein, another sedimentation velocity experiment was carried out at a speed of 45,000 rpm at 20 °C. Absorbance data were collected using a radial step size of 0.003 cm at 280 nm at three different concentrations: 23.4, 15.1, and 6.7 uM. Approximately 70 scans for each cell were collected and used for analysis. The sedimentation coefficient was determined to be 4.7 ± 0.1 S using the van Holde-Weischet analysis from Ultrascan. The average molecular weight was calculated to be 69 ± 5 kDa using 2-D Spectrum Analysis from Ultrascan (17, 18). This molecular weight corresponds to a homodimer since the molecular weight of a single subunit is 34.7 kDa.

Kinetic Measurements and Data Analysis

The kinetic measurements were performed with a SPECTRAmax-340 plate reader or a CARY 100 spectrophotometer. The hydrolysis of lactones was monitored using a pH-sensitive colorimetric assay (19). Protons released from the carboxylate product were measured using the pH indicator cresol purple. The reactions were performed in 2.5 mM Bicine, pH 8.3, containing 0.2 M NaCl, 0.01–6 mM of the lactone substrate, 0.1 mM cresol purple and various amounts of Dr0930. The final concentration of DMSO was 1.4%. The change in absorbance at 577 nm was monitored in a 96-well UV-visible plate. The conversion factor (ΔOD/mol of H+) was obtained from an acetic acid titration curve at 577 nm (ε = 1.88 × 103 M−1, 1.4% DMSO). The protein was stored in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and exchanged with 10 mM Bicine, pH 8.3, with a PD-10 column before use. The lactones were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted to 2.5 mM Bicine, pH 8.3. A background rate was observed in the absence of substrate due to acidification by atmospheric CO2. The background rate (5–10 mOD/min) was independent of substrate concentration and subtracted from the initial rates. Measurement of the phosphotriesterase activity was conducted in 50 mM Hepes, pH 9.0, using paraoxon as the substrate. The reaction was monitored spectrophotometrically by following the formation of p-nitrophenol at 400 nm.

Kinetic parameters were obtained by fitting the initial rates directly to equation 1, where ν is the initial velocity, Et is the enzyme concentration, kcat is the turnover number, [A] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis constant.

| (1) |

Crystallization and Data Collection

Crystals of Zn2+-bound Dr0930 were grown by vapor diffusion at room temperature. The protein solution contained Dr0930 (11.2 mg/mL) in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 0.5 mM ZnCl2; the precipitant contained 1.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.5, and 0.2 M Li2SO4. Crystals appeared in 4 days and exhibited diffraction consistent with the space group P3121, with one molecule of Dr0930 per asymmetric unit. These crystals contain 60% solvent and are characterized by a Vm of 3.1 Å3/Da, both of which are on the high side of the distribution exhibited by protein crystals. Prior to data collection, the crystals were transferred to cryoprotectant solutions composed of their mother liquors supplemented with 20% glycerol. After incubation for ~15 seconds, the crystals were flash-cooled to 100 K in a nitrogen stream. Data for the Zn2+-bound Dr0930 were collected to a resolution of 2.1 Å at the NSLS X4A beamline (Brookhaven National Laboratory) on an ADSC CCD detector. Intensities were integrated and scaled with DENZO and SCALEPACK (20). Data collection statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Native Dr0930 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | NSLS X4A |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.97915 |

| space group | P3121 |

| # of molecules in a.u. | 1 |

| Unit cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 61.505 |

| c (Å) | 205.94 |

| resolution (Å)a | 25-2.1 (2.18-2.1) |

| unique reflections | 26992 |

| completeness (%)a | 98.7 (98.2) |

| Rmergea | 0.041 (0.103) |

| Average I/σa | 45.4 (33.1) |

| Refinement | |

| resolution | 25.0-2.1 |

| Rcryst | 0.232 (0.315) |

| Rfree | 0.277 (0.352) |

| rmsd for bonds (Å) | 0.005 |

| rmsd for angles (°) | 1.4 |

| # of protein atoms | 2440 |

| # of waters | 384 |

| # of ions | 2 Zn2+ |

| PDB entry | 3FDK |

Numbers in parentheses indicate values for the highest resolution shell.

Structure Determination and Refinement

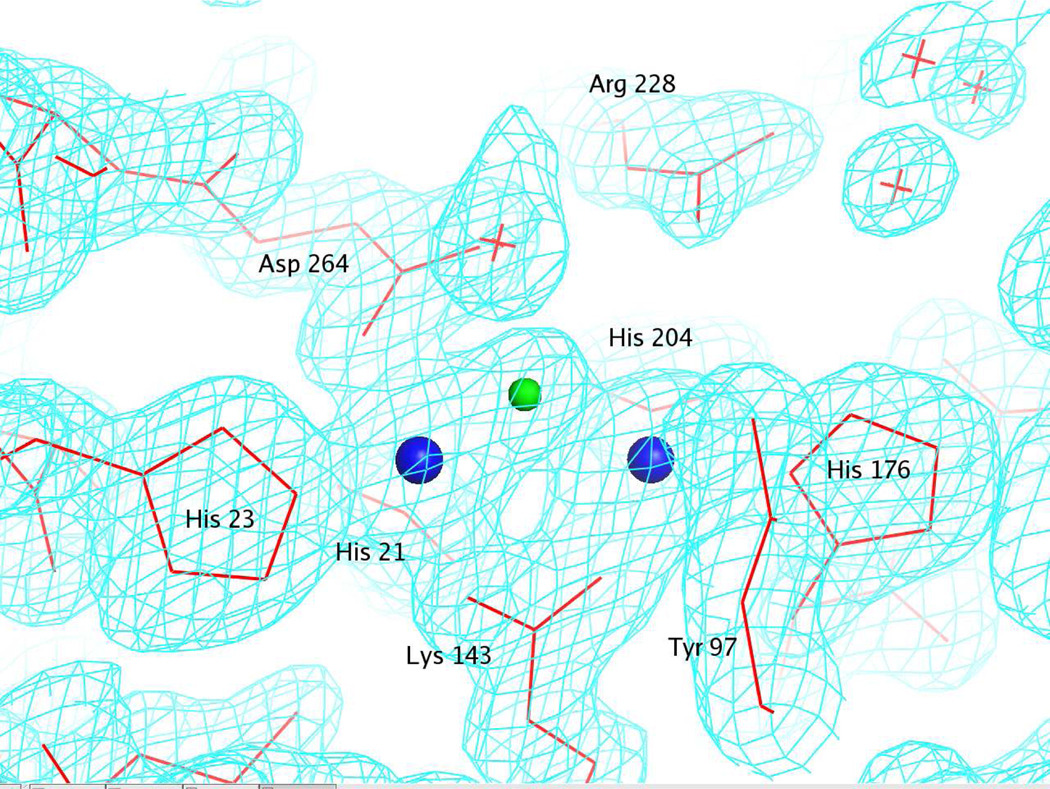

The structure of Zn2+-bound Dr0930 was determined by molecular replacement with PHASER (21), using the coordinates of the phosphotriesterase from P. diminuta (pdb file: 1HZY) as the search model (30.8% sequence identity). Iterative cycles of automatic model rebuilding with ARP (22), manual rebuilding with TOM (23) and refinement with CNS (24) were performed. The model was refined at 2.1 Å with an Rcryst of 0.232 and an Rfree of 0.277. The final structure contained protein residues 2–323, 384 water molecules and two well-defined Zn2+ ions. Representative electron density of the active site of Dr0930 liganded with two Zn2+ ions is shown in Figure 1. Final crystallographic refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Representative electron density for the active site of Dr0930 contoured at 1.5σ. Electron density shown was calculated to 2.1 Å resolution with the coefficients (2Fo-Fc). The metal ions are depicted as blue spheres and the bridging hydroxide is shown as a green sphere.

Docking of High-Energy Intermediates

In parallel with the experimental elucidation of the catalytic function of Dr0930, docking calculations were carried out in order to identify potential substrates. These calculations employed the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) LIGAND library of biogenic compounds (25, 26), a database of small molecules that are found in nature. This database consists of diverse molecules, often with unrelated chemical functionalities; it was not tailored to Dr0930 except to the extent that only molecules bearing functionalities known to be acted on by members of the amidohydrolase superfamily were considered, but this still included about 40% of all the molecules in KEGG. In the version of KEGG used here, the molecules had been modified to resemble the tetrahedral or trigonal bipyramidal intermediates that are observed along the reaction coordinate of the enzymatic reactions that the AHS is known to catalyze. It has been shown previously that the high-energy intermediate (HEI) states of potential substrates are preferentially recognized by members of the AHS and that docking calculations utilizing them are more likely to yield the correct substrate (7, 9). The library of HEIs specific to reactions of the amidohydrolase superfamily was used (7, 9). Briefly, all molecules of the KEGG library that contained one or more of the 19 functionalities that are involved in any of the known amidohydrolase reactions were converted to their respective high-energy forms. As most of the AHS reactions are nucleophilic substitutions involving an attack by a hydroxide leading to a tetrahedral intermediate state, all possible stereoisomers corresponding to attacks from the re- and si-faces were generated. In addition, the protonated and unprotonated forms of the leaving groups were prepared. This protocol led to approximately 22 500 different high-energy forms of the 4207 molecules in KEGG that featured a reactive group recognized by an AHS enzyme. Library generation and docking were done in an unbiased and general way, as we did not know what the substrates for the enzyme might be. We note that the molecule ultimately found to have the highest turnover rate, 11, was not part of the original KEGG library, and it was thus individually converted to a HEI, applying the same settings as for the entire library, so that we could model its enzyme-bound configuration by docking.

Docking was carried out with DOCK 3.5.54 as described previously (9) rank-ordering the molecules by a physics-based score consisting of van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation terms. After docking, poses were filtered based on a distance criterion to ensure that the reactive group was within 3.5 Å of the catalytic nucleophile and thus in a potentially catalytically competent geometry. The top 500 poses according to the score were inspected visually to ascertain this.

Construction, Expression, and Purification of PTE-Dr0930 Chimera

The binuclear metal centers in Dr0930 from D. radiodurans and PTE from P. diminuta are essentially identical. To identify the structural determinants for the differences in substrate specificities between these two enzymes a structure-based sequence alignment was performed using PyMOL. The structure-based sequence alignment was used to identify the precise locations of the eight specificity loops at the C-terminals ends of the central β-strands in each protein. A chimeric protein was designed that substituted the eight specificity loops in Dr0930 with the corresponding loops from PTE. The gene for the chimeric Dr0930-PTE was chemically synthesized by Mr. Gene (http://mrgene.com) and optimized for expression in E. coli with respect to codon usage and overall GC content. An amount of 5 µg of lyophilized plasmid DNA was supplied by the manufacturer with the synthesized fragment inserted between KpnI and SacI restriction sites in the vector pGA18 with ampicillin resistance. The KpnI restriction site at the 5’-end of the fragment is followed by an EcoRI and a NdeI restriction site which comprises the ATG codon of the gene. At the 3’-end of the gene, two stop codons were inserted followed by HindIII and SacI restriction sites. The designed gene carried internal restriction sites embedding the loops 7 (restriction sites NcoI and AclI) and 8 (restriction sites TspRI and AatII).

The PTE-Dr0930 chimeric gene was inserted into pET-21a(+) and pET-28a(+) vectors, using the restriction sites NdeI and HindIII. To analyze the solubility of the protein, different expression cells (T7 Express, T7 Express Rosetta, BL21 (DE3) RIPL, ArcticExpress and ArcticExpress RIL) were transformed with these vectors carrying the synthetic gene. The chimeric protein was expressed in an analytical scale with 1.0 mM ZnCl2 in the culture medium overnight at different temperatures (13, 20, 30, and 37 °C). All conditions yielded only insoluble protein. It was possible to purify the chimeric protein from the insoluble fraction of the T7 Express cells (transformed with pET-21a(+) containing the synthetic gene and grown in 250 mL of ZnCl2-lacking LB medium) by refolding it in the presence of ZnCl2. To solubilize the protein, the pellet was washed with 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, and then dissolved in 20 mL of 6 M guanidinium chloride (GdmCl), 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with continuous stirring. Subsequently, 20 mL of 1 M GdmCl, 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, was added and the solution was incubated for another 30 minutes at room temperature with continuous stirring. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant solution was transferred to a new reaction vessel and mixed with 70 mL of 2 M GdmCl, 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.5. This solution was dialyzed three times against 5 L of 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, 50 mM bicarbonate and 100 µM ZnCl2.

Results

Cloning, Expression and Purification of Dr0930

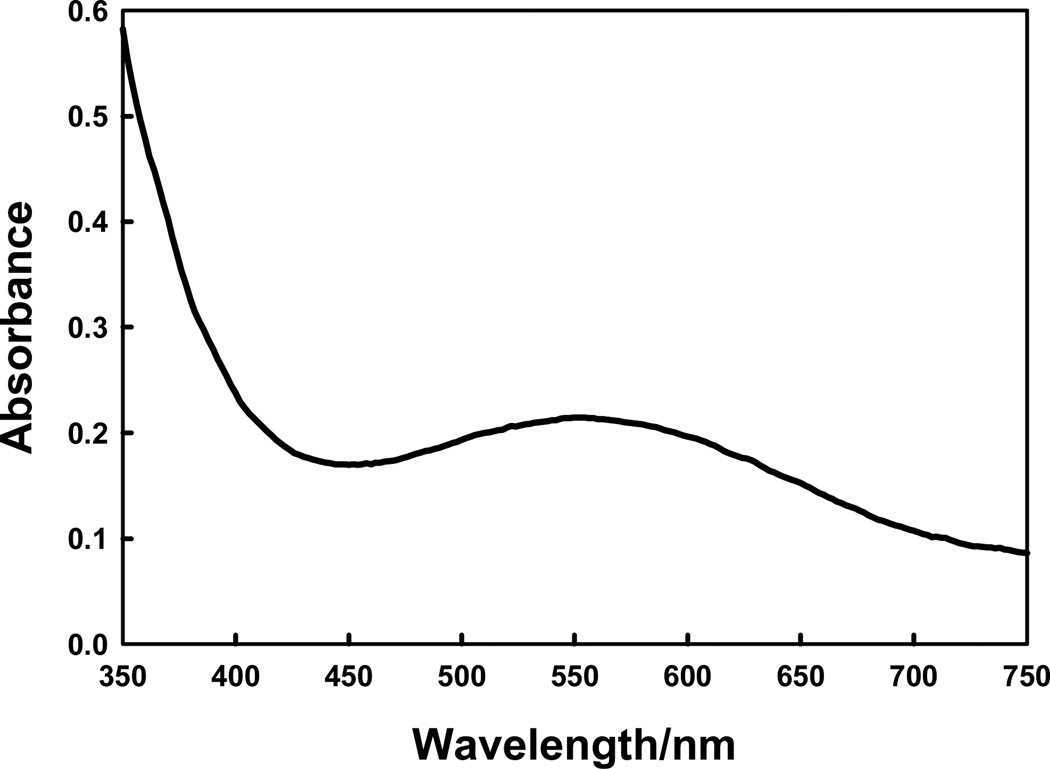

The gene for Dr0930 from D. radiodurans was successfully cloned and inserted into the vector pET-30a(+) for expression in E. coli. The protein expresses well in E. coli after induction with IPTG in the presence of divalent metal ions (ZnAc2, MnCl2 or CoCl2) in the culture medium. A total yield of 30 – 125 mg of homogeneous protein was obtained from 1–3 L of LB medium. The protein purity was estimated to be greater than 95% as judged by PhastGel electrophoresis. N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis for the first 6 amino acid residues gave the sequence as MTAQTV, which is consistent with the first six amino acid residues as deduced from the DNA sequence. The enzyme expressed in the presence of 1.0 mM ZnAc2 in the growth medium was found to contain 1.2 equivalents of zinc and 0.4 equivalents of iron per subunit. The concentrated enzyme was intensely purple in color. Shown in Figure 2 is the visible absorption spectrum of the protein at a concentration of 450 µM. The absorption maximum is at 550 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 455 M−1 cm−1.

Figure 2.

Visible absorption spectrum for Dr0930 at a subunit concentration of 450 µM.

Structure of Dr0930

Dr0930 adopts an (β/α)8 structural fold. The protein monomer is composed of a (β/α)7β-barrel with N-terminal and C-terminal extensions of the chain from both sides of the barrel. The following chain segments are included in the eight β-strands of the barrel: β1 (residues 17–26), β2 (61–66), β3 (89–94), β4 (141–146), β5 (173–177), β6 (199–202), β7 (223–226) and β8 (259–269). The N-terminal extension of the chain includes a β-loop (3–10). The C-terminal extension includes three distorted α-helices (278–284, 291–303 and 307–322). The last α-helix closes the entrance to the barrel from the N-terminal side. Two long segments between strands β1 and β2 and between strands β3 and β4 of the barrel contain two helices each. The remaining segments between the β-strands of the barrel each contain a single helix.

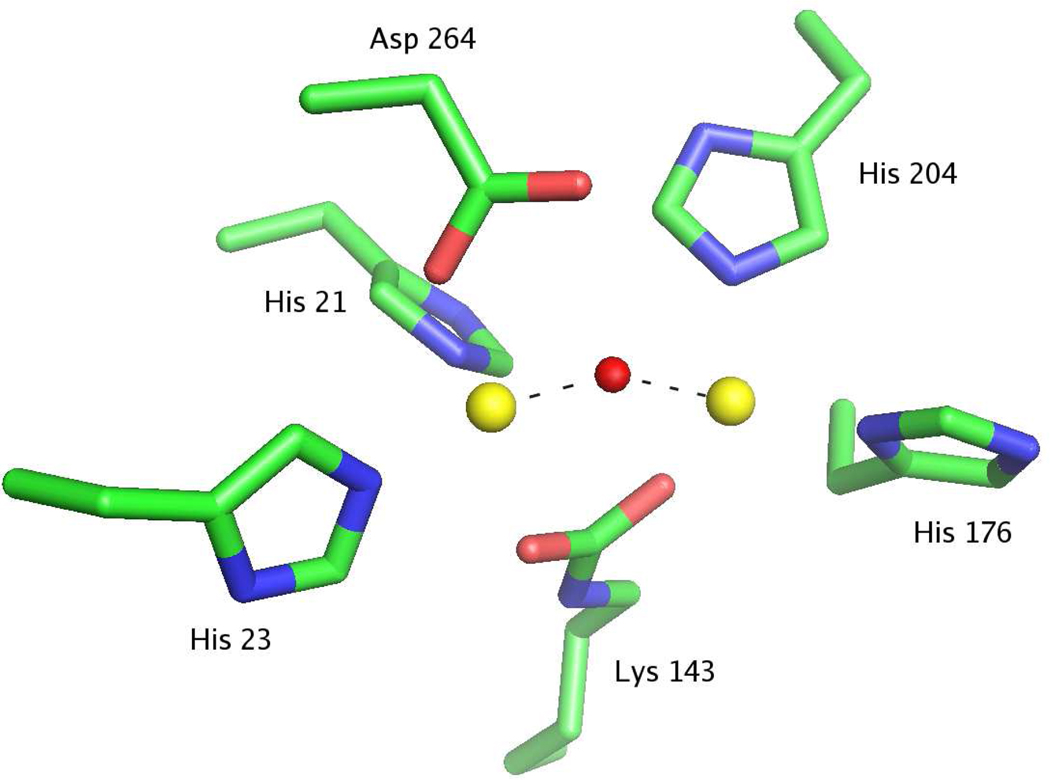

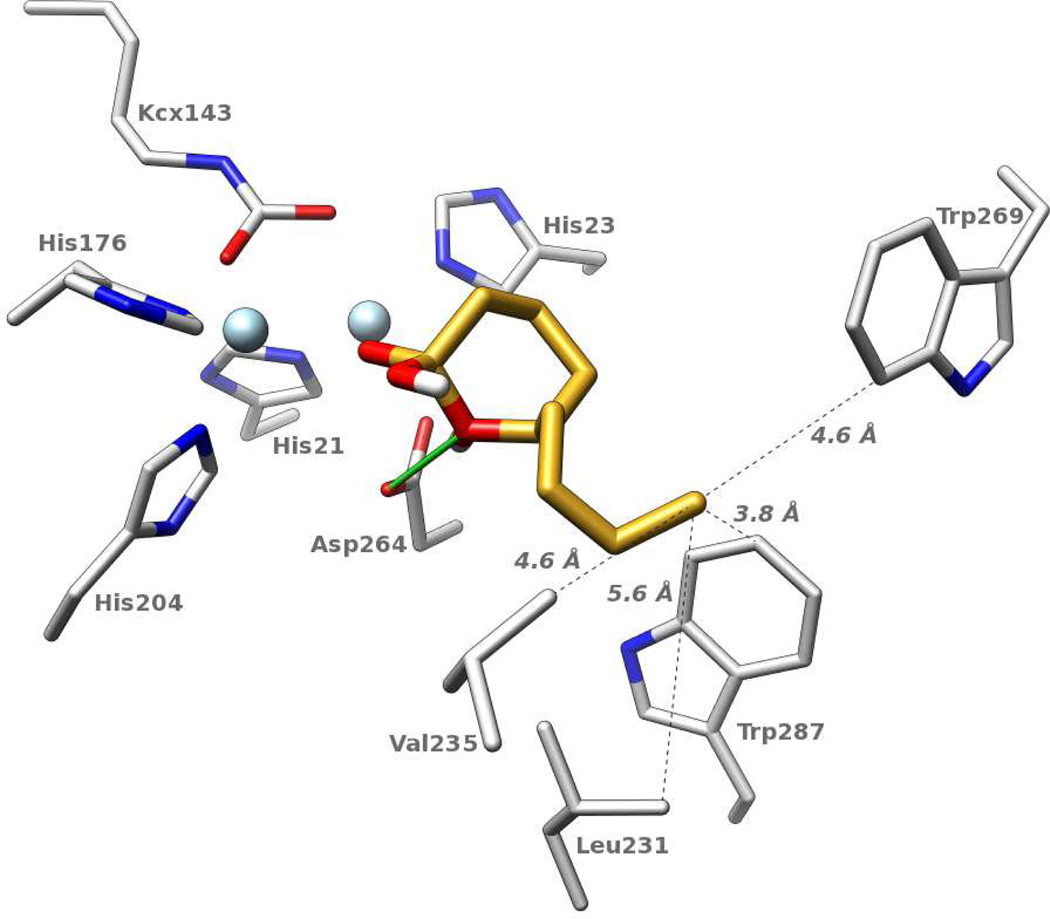

The active site is located at the C-terminal end of the barrel and is open to external solvent. Two metal ions are bound in the active site; the most deeply buried and most solvent exposed cations are denoted as α and β, respectively. The α-cation is coordinated by His-21 and His-23 from strand β1, Asp-264 from strand β8, and the carboxylated Lys-143 from strand β4 (Figure 3). The β-cation is coordinated by His-176 from strand β5, His-204 from strand β6, and the carboxylated Lys-143. A bridging hydroxide ion serves as an additional ligand for both cations. The inter-atomic distance between the two metal ions is 3.4 Å, with distances to the bridging hydroxide of 1.9 and 2.1 Å. No other water molecules at distances less than 3.8 Å from both Zn2+ ions or from the bridging hydroxide were detected.

Figure 3.

Model for the active site of Dr0930. The α-metal ion (left) and the β-metal ion (left) are shown as yellow spheres and the bridging hydroxide as a red sphere.

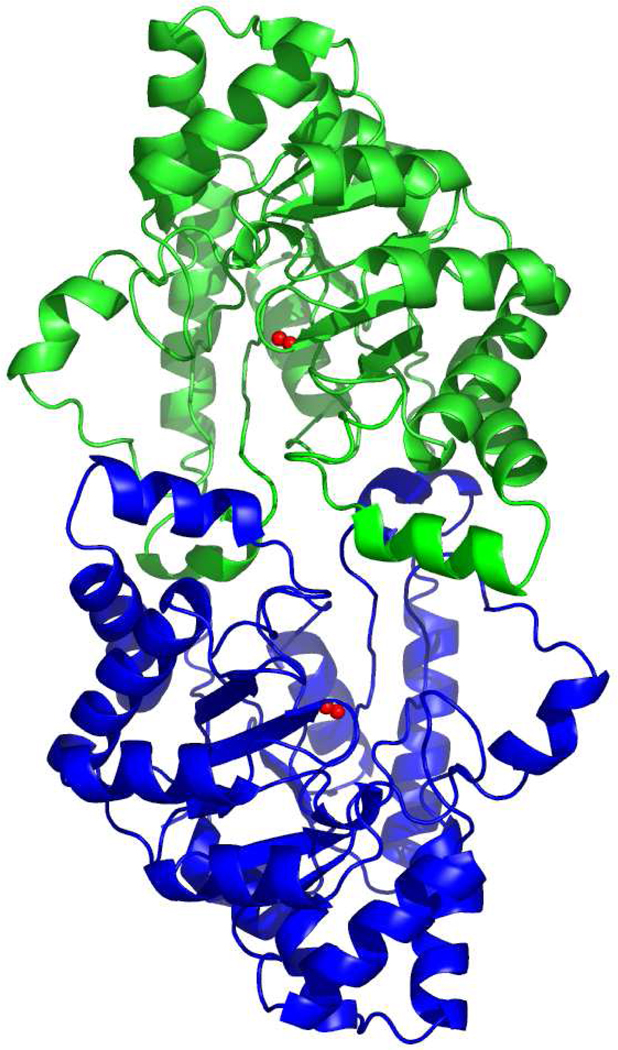

The Dr0930 monomers are related by a crystallographic 2-fold axis and form an apparent dimer in the current crystal structure (Figure 4), which buries a total surface area of 2835 Å2 at the interface. Loop 1 (after strand β1) and loop 3 (after strand β3) of each molecule make extensive contacts with the 2-fold-related molecule. For example, Thr-36 OG1 (loop 1) forms hydrogen bonds to Ala-133* N and Glu-127* OE2 of the adjacent molecule. Thr-105, Phe-109 and Leu-113 (loop 3) participate in various hydrophobic interactions with the residues of the adjacent molecule Pro-29*, Tyr-28*, Trp-269*, and Pro-274*, some of which are not far from the entrance to the active site of the symmetry mate. There are also some polar interactions between residues in loop 3 and the residues of the symmetry related molecule: Thr-105 OG1 – Glu-101* O, Tyr-106 OH – Asp 34* OD2, Tyr-106 OH – Arg 272* N, Arg 110 NH1- Pro 273* O, and Arg 110 NH1 – Arg 272* O.

Figure 4.

Ribbon representation of the Dr0930 dimer. The molecules are oriented with the 2-fold axis perpendicular to the plane of the page. The metal ions at each active site are shown as red spheres. There are extensive intermolecular interactions formed by the loops L1 and L3 from each monomer.

The phenolic oxygens of Tyr-28, Tyr-97 and Tyr-98 are 8.93, 3.48, and 8.15 Å away, respectively, from the β-cation. To determine if the absorbance at 550 nm of the wild type enzyme is due to a charge transfer complex between any of these tyrosines and the β-cation, they were individually mutated to phenylalanine. The purified Y28F mutant contained 1.1 equivalents of Zn and 0.4 equivalents of iron and the protein absorbed at 550 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 490 M−1 cm−1. The Y97F mutant contained 1.4 equivalents of zinc and 0.3 equivalents of iron but no absorbance could be detected at 550 nm at concentrations up to 5 mg/mL. The Y98F mutant adsorbed at 550 nm with an extinction coefficient of 460 M−1 cm−1. This mutant contained 0.9 equivalents of zinc and 0.2 equivalents of iron. Enzyme expressed in the presence of the iron chelator 2’2-bipyridal and 1.0 mM Mn2+ contained less than 0.1 equivalent of iron and was transparent in the visible spectrum (data not shown).

Docking Calculations

The initial attempt to dock the high-energy intermediate (HEI) version of the KEGG database to the x-ray structure of Dr0930 failed as few molecules were docked in a pose that was even remotely close to the metal ions, a necessary condition for successful turnover. Upon inspection of the binding site it became clear that the side chain of Arg-228 was blocking access to the catalytic center. Consequently, the side chain of this residue was rotated 180° around the Cγ-Cδ bond and minimized with CHARMM (27), using the CHARMm22 force field (28). This conformation is lower in energy compared to the original one, which is due, in part, to the decreased distance between Arg-228 and the side chain of Asp-206 resulting in a more favorable electrostatic interaction. In the second virtual screen of the KEGG HEI database, in which DOCK found poses that placed the reactive center, represented by the high-energy intermediate, within the distance of 3.5 Å for 1821 molecules, a substantial enrichment of lactones was observed. Among the top 100 docking-ranked KEGG metabolites, there were 55 high energy intermediates that were docked in a catalytically competent manner, 21 of which were lactones (including three in the top 10). Consistent with this ranking, lactones were identified as preferred substrates of Dr0930 by experimental assay. Among the high ranking lactones that were turned over were molecules ranking 173 (compound 6), 325 (compound 9), 349 (compound 1) and 417 (compound 13). After visual inspection of the 500 highest-ranking molecules, lactones ranking 89 and 216 were also suggested based on their docking prediction and tested experimentally, but were not hydrolyzed measurably by the enzyme. In addition to these lactones, nine other high-ranking molecules, including several lactams, were tested after they had been selected as potential substrates because of their docking ranks and predicted geometries, but none of them was turned over. Subsequently, the substrate with what turned out to be the highest turnover rate, 11, was docked into the structure of Dr0930, mostly to investigate its proposed structure and stereochemical preferences. This compound had a docking score that, had it been included in the initial KEGG-derived HEI database, would have ranked at 72 overall (see Methods). Compound 11 is a δ-lactone, the corresponding γ-lactone, 6, ranks at 173.

To investigate stereochemical preferences, all possible enantiomer combinations of compounds 6 and 11 were compared directly. As the carbon atom at the base of the hydrophobic tail is chiral, this comparison included four different species: re-R, re-S, si-R, and si-S. For both molecules, docking vastly prefers an orientation that corresponds to a hydrophilic attack from the si-face (Figure 5 depicts the highest-ranking pose of 11). Among the top 50 poses (i.e., orientations and conformations), 46 are such that they could be attacked by a hydroxyl anion positioned between the metal ions. Of these, 20 are si-R; 12 are si-S; 3 are re-R; and 11 are re-S.

Figure 5.

Computed binding mode of compound 11 (golden carbons). Metal ions are depicted in light blue. The dashed lines indicate the distances between the terminal methyl group of compound 11 and selected residues within the active site. Additional details are presented in the text.

We also looked at the predictions for the N-acyl homoserine lactones in detail. It has been demonstrated that this class of molecules is turned over by Sso2522 and it was an open question whether the same is true for Dr0930. Although there were 7 N-acyl homoserine lactones in the docked library, none of them was placed in a catalytically competent pose. The docking of the organophosphate triesters was also investigated. In total, six such molecules can be found in the database, but only one docked in a sensible pose. This molecule had a favorable score, placing it at rank 5. However, we were unable to demonstrate that this compound, 2,2-chlorovinyl dimethyl phosphate (dichlorvos) is a substrate for Dr0930. The value of kcat is less than 4 × 10−3 s−1.

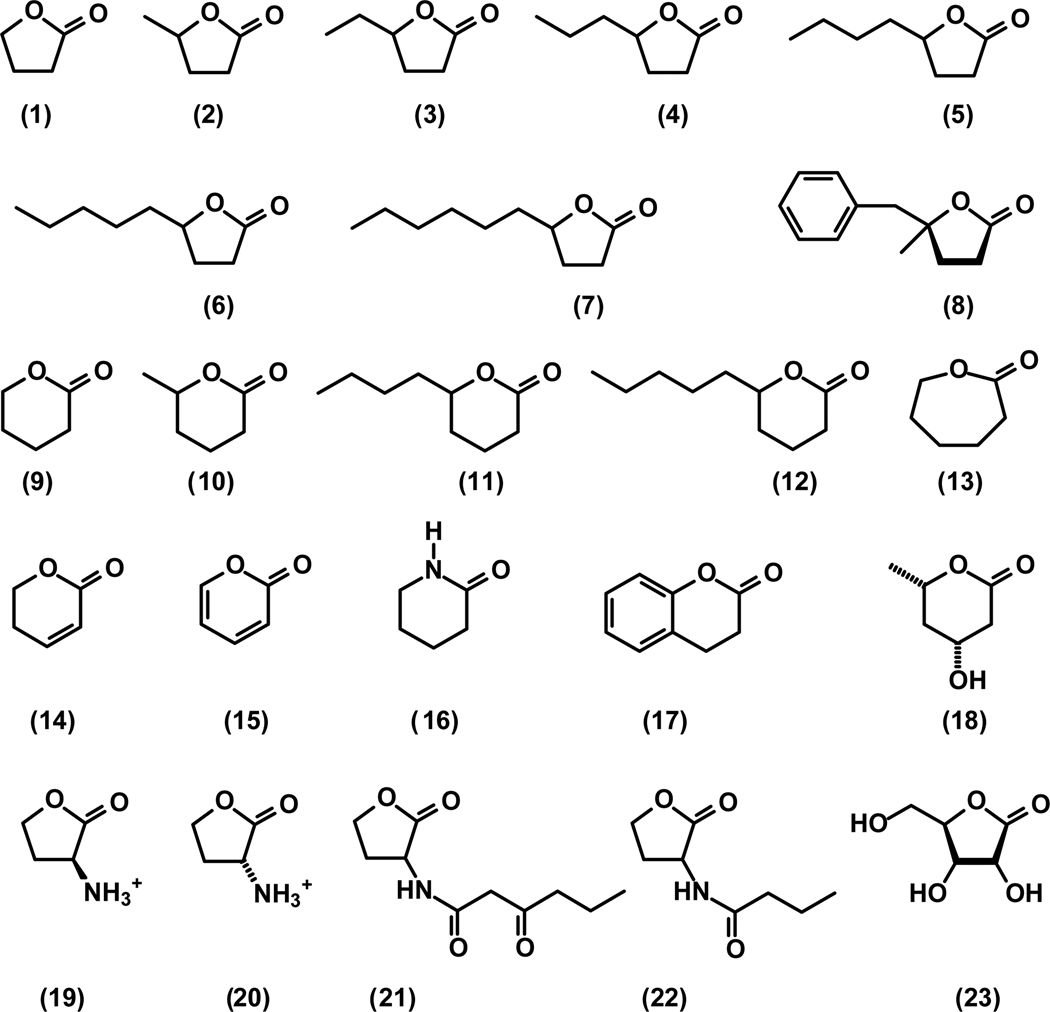

Substrate Specificity and Kinetic Measurements

The catalytic activity of Dr0930 was initially examined for the hydrolysis of organophosphate triesters, diesters, and monoesters. No catalytic activity could be detected with ethyl 4-nitrophenyl phosphate or 4-nitrophenyl phosphate. Slow hydrolysis could be detected with the organophosphate triester, paraoxon (diethyl 4-nitrophenyl phosphate) and the values of kcat, Km and kcat/Km were determined to be 0.072 min−1, 1.4 mM, and 0.83 M−1 s−1, respectively. These results indicated that the native substrate profile of this enzyme does not involve phosphate esters. No activity could be detected with phenyl acetate but significant hydrolytic activity could be detected with a number of lactones identified in the initial screening protocols. We measured the catalytic activity of Dr0930 with an array of lactones and found that this enzyme can efficiently hydrolyze γ- and δ-lactones. The structures of these compounds are given in Scheme 1. The kinetic parameters for the Zn-, Mn- and Co-substituted forms of Dr0930 are presented in Table 2 and the kinetic constants for the three tyrosine to phenylalanine mutants are given in Table 3. The best substrates identified to date are γ- or δ-lactones with an alkyl substituent attached to the carbon adjacent to the ring oxygen. For Mn/Mn-Dr0930 the values of kcat and kcat/Km for δ-decanoic lactone are 460 s−1 and 1.3 × 106 M−1 s−1, respectively. No activity could be detected with compounds 14 – 23 with turnover numbers greater than 0.01 s−1. The structures for additional compounds (S24 – S37) that were found to be inactive with the Zn- and Mn-substituted forms of Dr0930 are presented in the Supporting Information as Figure S1.

Scheme 1.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for Zn/Zn-, Mn/Mn- and Co/Co-Dr0930 at pH 8.3.

| Compound | Dock Rank |

Zn/Zn-Dr0930 | Mn/Mn-Dr0930 | Co/Co-Dr0930 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) | ||

| 1 | 349 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | (9.4 ± 1.3) × 102 | ||||||

| (R/S)-2 | nla | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | (3.9 ± 0.2) × 103 | 155 ± 5 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 104 | |||

| (R)-2 | nl | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | (5.5 ± 0.2) × 103 | 163 ± 3 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | (2.5 ± 0.1) × 104 | |||

| (R/S)-3 | nl | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | (6.9 ± 0.5) × 103 | 260 ± 9 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | (7.7 ± 0.5) × 104 | |||

| (R/S)-4 | 172 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | (3.8 ± 0.3) × 104 | 220 ± 4 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | (6.4 ± 0.4) × 105 | |||

| (R/S)-5 | nl | 2.0 ± 0.04 | 0.063 ± 0.007 | (3.2 ± 0.4) × 104 | 212 ± 12 | 0.57 ± 0.07 | (3.7 ± 0.2) × 105 | |||

| (R/S)-6 | 173 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | (4.1 ± 0.1) × 104 | 95 ± 4 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | (2.5 ± 0.2) × 105 | |||

| (S)-6 | 173 | 14 ± 1 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | (9.3 ± 1) × 104 | 230 ± 12 | 0.58 ± 0.11 | (4.0 ± 0.3) × 105 | 70 ± 2 | 0.09 ± 0.1 | (8 ± 1) × 105 |

| (R/S)-7 | nl | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 104 | 100 ± 4 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | (2.9 ± 0.4) × 105 | |||

| (S)-8 | nl | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | (5.4 ± 0.9) × 103 | 87 ± 2 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 105 | 17 ± 1 | 0.70 ± 0.06 | (2.4 ± 0.2) × 104 |

| 9 | 325 | 48 ± 3 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | (1.6 ± 0.2) × 104 | 93 ± 3 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | (2.8 ± 0.2) × 104 | |||

| (R/S)-10 | nl | 32 ± 1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | (1.8 ± 0.1) × 104 | 88 ± 7 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | (3.8 ± 0.7) × 104 | |||

| (R/S)-11 | 72 | 42 ± 1 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | (4.2 ± 0.7) × 105 | 203 ± 5 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | (1.6 ± 0.1) × 106 | 180 ± 5 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 106 |

| (R/S)-12 | nl | 16 ± 1 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 105 | 460 ± 12 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 106 | 180 ± 7 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | (9.5 ± 1.6) × 105 |

| 13 | 417 | ND | ND | 59 ± 4 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | (6.9 ± 1.7) × 102 | |||

not in original KEGG library

Table 3.

Properties of Tyrosine to Phenylalanine Mutants of Dr0930a.

| Protein | color | metal content |

kcat (s−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zinc | iron | |||||

| Wild-type | purple | 1.2 | 0.4 | 42 ± 1 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | (4.2 ± 0.7 × 105 |

| Y28F | purple | 1.1 | 0.4 | 26 ± 1 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | (2.7 ± 0.4) × 105 |

| Y97F | colorless | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | (1.7 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| Y98F | purple | 0.9 | 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | (1.8 ± 0.2) × 104 |

Hydrolysis of compound 11 at pH 8.3.

Loop Transplantation from PTE to Dr0930

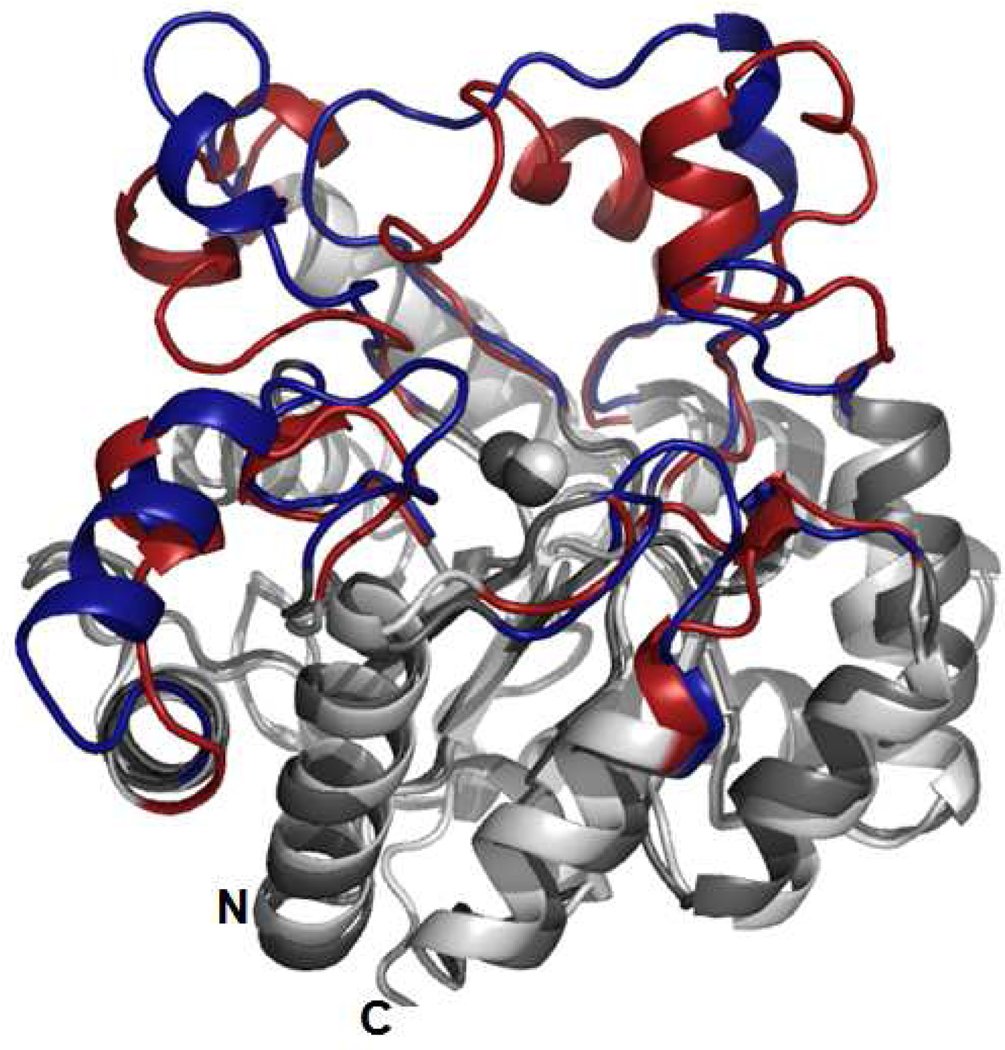

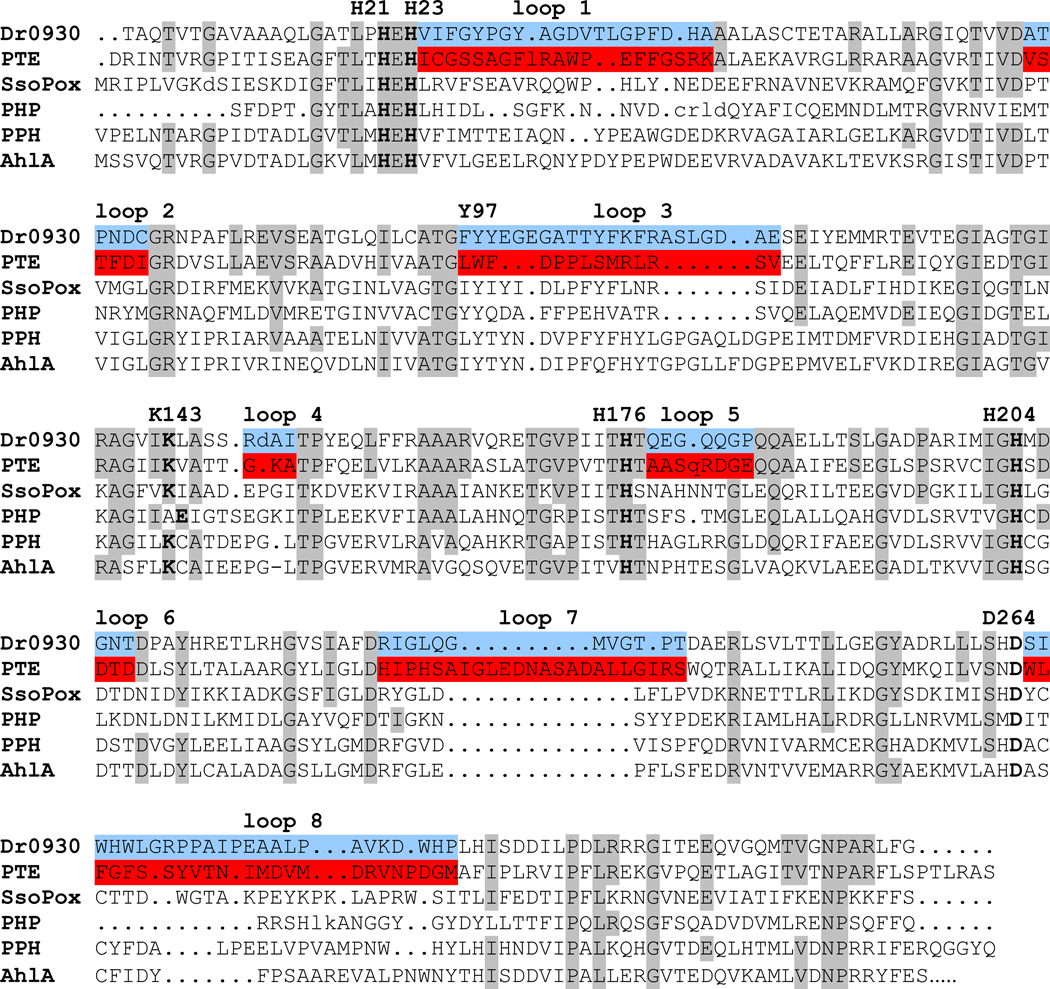

The binuclear metal center within the active site of Dr0930 is identical with the one found in the active site of the phosphotriesterase from P. diminuta. Shown in Figure 6 is a structural superposition between these two proteins. It is clear from this comparison that the central β-barrel and interconnecting α-helices superimpose quite nicely and that the major structural differences between these two enzymes lie predominantly within the composition and conformation of the eight βα-loops that interconnect the eight β-strands and the eight α-helices. However, Dr0930 catalyzes the hydrolysis of paraoxon more than a million-fold more slowly than does PTE from P. diminuta. Since the substrate specificity of β/α-barrel proteins is apparently dictated by the residues located at the C-terminal end of the β-strands and the βα-loops, a chimeric protein was designed where the 8 βα-loops found close to the active site of PTE replace the corresponding loops in Dr0930. This was done to determine whether the inherent structural and dynamic information embedded within the eight loops in PTE is sufficient to increase the promiscuous triesterase activity in Dr0930. A sequence alignment based upon the structural alignment between PTE and Dr0930 is presented in Figure 7. Shown in red are the specific residues for the 8 βα-loops of PTE that were swapped for the eight corresponding loops of Dr0930 (shown in blue).

Figure 6.

Structural superposition between Dr0930 and PTE. The eight βα-loops from PTE are depicted in red whereas the eight βα-loops from Dr0930 are depicted in blue. The central β-barrel, the surrounding α-helices, and the two zinc atoms for both proteins are depicted in shades of grey.

Figure 7.

Structure based sequence alignment between PTE (gi|54778533) and Dr0930 (gi|15805954). The specific amino acids of PTE that replaced those of Dr0930 in the PTE-Dr0930 chimera are shown in red and blue, respectively. Identical residues between PTE and Dr0930 are shown in light grey. Residues involved in metal complexation are printed in bold and labeled. The relationship of these sequences for those found in Sso2522 (also known as SsoPox; gi|15899258), PTE homology protein (PHP; gi|16131257), putative parathion hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (PPH; gi|15839610) and N-acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Rhodococcus erythoropolis (AhlA; gi|46947344) are shown for comparison.

The gene for the chimeric PTE-Dr0930 protein was synthesized and attempts were made to express the protein under a variety of conditions. However, in every case the protein was found to be insoluble. The protein was solubilized by the addition of 6 M GdmCl, which was then removed stepwise by dialysis against 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 100 µM ZnCl2 and 50 mM bicarbonate, to induce folding. A total of 3.6 mg of the soluble chimeric protein was isolated that was judged 80% pure by SDS gel electrophoresis. However, no phosphotriesterase activity was detectable for the PTE-Dr0930 chimera (kcat < 10−4 s−1).

Redesign of Dr0930 Active Site

The three-dimensional structure of PTE with a bound substrate analogue has been used to identify those residues that come together to form the substrate binding pocket in the active site (29). The twelve most significant residues include G60, I106, W131, F132, H254, H257, L271, L303, F306, S308, Y309, and M317. The corresponding residues within the active site of Dr0930 are F26, C72, Y97, Y98, R228, L231, V235, I266, W269, R272, P273, and P282, respectively. In addition, H254 in PTE is hydrogen bonded to D233 and the corresponding residue in Dr0930 is G207. In an attempt to enhance the promiscuous triesterase activity of Dr0930, some of these residues were replaced with the corresponding residues found within the active site of PTE. These substitutions were done singularly and in combination with one another. The mutant forms of Dr0930 were purified to homogeneity and their activity toward the hydrolysis of paraoxon was measured at pH 9.0. The results are summarized in Table 4. The most active mutant was F26G/C72I with a kcat of 1.14 min−1 and kcat/Km of 7.7 M−1 s−1. The turnover number of this mutant is enhanced 16-fold relative to the wild type enzyme.

Table 4.

Properties of Site-Directed Mutants of Dr0930a.

| Protein | color | metal content |

kcat (min−1) |

Km (mM) |

kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zinc | iron | |||||

| wild type | purple | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.072 | 1.4 | 0.83 |

| F26G | black | 0.85 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 8.3 | 1.1 |

| C72I | purple | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.023 | 1.4 | 0.29 |

| F26G/C72I | purple | 0.64 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 2.7 | 7.7 |

| Y98F | purple | 1.17 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 1.8 | 0.55 |

| F26G/C72I/Y97W/Y98F | yellow | 0.41 | 0.66 | - | - | 0.91b |

| G207D/R228H/L231H | purple | 1.29 | 0.47 | ndc | nd | nd |

| F26G/C72I/Y97W/Y98F/G207D/R228H/L231H | yellow | 0.62 | 0.27 | nd | nd | nd |

Hydrolysis of paraoxon at pH 9.0.

The enzyme was not saturated up to a concentration of paraoxon of 3 mM.

nd – not detectable.

Discussion

Purification and Properties

Dr0930 from D. radiodurans was cloned and purified to homogeneity. The purified protein was found to contain a mixture of zinc and iron when expressed in a medium that was supplemented with added zinc. At high concentrations the protein was a deep purple in color with an absorption maximum at 550 nm. This property is reminiscent of the optical properties for purple acid phosphatase or uteroferrin (30). Those proteins contain a binuclear iron center and the visible spectrum has been proposed to be due to a charge transfer complex between a tyrosine and one of the two irons within the binuclear metal center (31). For uteroferrin the extinction coefficient for the Fe3+/Fe2+ complex is approximately 4,000 M−1 cm−1 (30). This is considerably higher than the value of 455 M−1 cm−1 measured for Dr0930 but the Fe content is less than 1 equivalent and the distribution of the iron between the two sites is not known. Nevertheless, the x-ray structure determination of Dr0930 showed that the phenolic oxygen of Tyr-97 is 3.5 Å away from the β-metal ion. Mutation of Tyr-97 to a phenylalanine resulted in a protein that was transparent in the visible region. In addition, expression of Dr0930 in a medium where the iron content was reduced with an iron-specific chelator in the presence of added Mn2+ resulted in protein that was transparent at 550 nm. Therefore, the intense purple color of the wild type Dr0930 is consistent with a charge transfer complex between Tyr-97 and iron bound to the β-metal position within the binuclear metal center. To the best of our knowledge the only other member of the AHS that absorbs in the visible region of the spectrum is the H55C mutant of Co/Co-PTE, which is bright green in color (32).

X-ray Structure Determination

The most similar protein structure to Dr0930 is Sso2522 from Sulfolobus solfataricus (PDB code: 2VC5) with a DALI (33) score of 42.5 and 28% overall sequence identity. The next most similar structural homologues for Dr0930 are the bacterial phosphotriesterases from P. diminuta (PDB code: 1HZY) and Agrobacterium radiobacter (PDB code: 2R1N), and the PTE homology protein from E. coli (PDB code: 1BF6), with DALI scores of ~41.0. The structures of Dr0930 and Sso2522 can be superimposed with an RMSD of 1.61 Å for 298 Cα-pairs. Superposition of Dr0930 with PTE from P. diminuta (PDB code: 1HZY) results in an RMSD of 1.32 Å for 276 Cα-pairs, and superposition with 2R1N results in an RMSD of 1.46 Å for 283 Cα-pairs. The superposition of Dr0930 with the PTE from P. diminuta is shown in Figure 6. The major differences involve the length and/or the conformation of the βα-loops. However, the two metal atoms, the bridging hydroxide and the direct metal ligands (His-21, His-23, His-176, His-204, Asp-264 and the carboxylated Lys-143 in Dr0930) are conserved between the two proteins and superimpose well. However the terminal water molecule bound to the most solvent exposed β-metal ion of PTE is absent in Dr0930.

The subunit organization of the Dr0930 dimer is very similar to that found in the crystal structures of the phosphotriesterases from P. diminuta (34) and A. radiobacter (35), and the lactonase Sso2522 from S. solfataricus (36). The dimer interfaces are all formed by interactions between the protruding L1 and L3 loops of each molecule and the protein chain of the adjacent molecule. These dimers are distinguished by slight differences in the relative orientation of their monomers. For example, the dimers of Dr0930 and P. diminuta phosphotriesterase (PDB code: 1HZY) superimpose with an RMSD of 2.5 Å for 568 Cα-pairs.

Computational Docking

Three lessons emerge from the in silico substrate predictions for this enzyme. First, docking of high-energy intermediates enriched the lactone functionality that was ultimately found to be recognized by Dr0930. Second, as compelling as this enrichment was, it was insufficient, in itself to identify those lactones best recognized by the enzyme. This has two origins. The very best ranking lactones by docking, that we were actually able to obtain and test (e.g., those ranked 30 and 148) were not hydrolyzed by the enzyme; these are false positives, as are the high-ranking lactams and the organophosphate triester that were tested but were not substrates. Dr0930 represents an enzyme where substrate recognition goes beyond physical complementarity of the enzyme for an HEI, and where the cost of forming the HEI from the ground state also plays an important role; this energy difference between ground and excited states presumably distinguishes many of the lactams from the lactones, and many of the stabilized lactones from those aliphatic δ-lactones that are among the best substrates. Conversely, the very best lactones that are commercially available, and that are recognized by the enzyme, are simply not found in KEGG. These are false negatives, but their absence reflects not so much on docking as on the library of molecules that are docked. Finally, the structural predictions allowed us to investigate the stereochemical preference of the reaction.

Substrate Specificity

Dr0930 has been shown to hydrolyze lactones but has a very weak phosphotriesterase activity. The best substrates identified to date are the γ- and δ-lactones with a hydrophobic chain attached to the carbon adjacent to the ring oxygen. Compound 12 has a value of kcat that exceeds 400 s−1 and a kcat/Km that is greater than 106 M−1 s−1. These values are in excess of those previously reported for other lactonases in the amidohydrolase superfamily: AhlA, PPH, and Sso2522 (12). However, we were unable to find any activity toward the hydrolysis of the N-acyl derivatives of homoserine lactone (compounds 21 and 22). This is perhaps not too surprising since the hydrophobic tails in these compounds extend from different parts of the lactone ring and the unsubstituted lactones (compounds 1 and 9) are poorer substrates than those with a hydrophobic extension at the carbon adjacent to the ring oxygen (Table 2). However, AhlA, PPH, and Sso2522 have all been reported to catalyze the hydrolysis of lactones such as 6 and 11 in addition to N-acyl homoserine lactones such as 22 (12). The reason for this difference in specificity is not at all clear.

The structure of Sso2522 (also known as SsoPox) from S. solfataricus complexed with the inhibitor N-decanoyl-l-homocysteine thiolactone has been determined (PDB code: 2VC7) (36). This enzyme, which possesses lactonase and a promiscuous phosphotriesterase activity, contains the same binuclear metal center as the bacterial phosphotriesterases and Dr0930 except that iron is bound to the α-site and cobalt is bound to the β-site (36). In the inhibitor complex of Sso2522, the carbonyl oxygen of the lactone ring interacts with the β-metal and Tyr-97. The sulfur in the lactone ring interacts weakly at a distance of 3.2 Å with the iron in the α-metal position. In the Sso2522 structure, the lactone ring is also contacted by the side chains of Arg-223, Leu-72, Val-27, and Ile-261. In Dr0930, these residues are replaced by Arg-228, Cys-72, Phe-26, and Trp-269. In Sso2522 a long hydrophobic channel accommodates the aliphatic tail of the N-acyl homocysteine inhibitor and is composed of the side chains of Phe-229, Leu-228, Leu-226, Trp-278, Thr-265, Ala-275, and Leu-274 (36). A long hydrophobic channel accommodating the substrate aliphatic chain in Sso2522 is also present in the Dr0930 structure. The corresponding residues in Dr0930 are Val-235, Met-234, Leu-231, Trp-287, Trp-269, Val-284, and Ala-283.

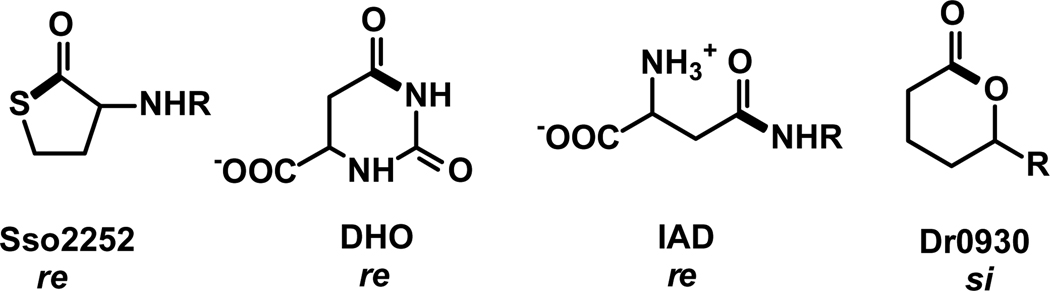

It is interesting to note that in the structure of Sso2522 with the N-acyl homocysteine lactone inhibitor, the bridging hydroxide is poised to attack the re-face of the thiolactone ring (shown in Figure 8). This facial selectivity is at odds with that observed for other members of the amidohydrolase superfamily with bound substrates or inhibitors.2 For example, in the complex of dihydroorotase (DHO) with dihydroorotate, the bridging hydroxide is positioned to attack the re-face of the amide bond (37, PDB code: 1J79). The same facial selectivity is observed in the complex of iso-aspartyl dipeptidase (IAD) with the substrate β-Asp-His (38, PDB code: 1YBQ). This selectivity is further supported by the orientation of a methyl phosphonate transition state inhibitor in the active site of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine 6-phosphate deacetylase (NagA) (PDB code: 2P53) (39). The facial selectivity observed in DHO, IAD, and NagA optimally position the invariant aspartate residue from the end of β-strand 8 to transfer the lone proton from the bridging hydroxide to the leaving group during the transformation from substrate to the hydrolyzed products. In the catalytic mechanism proposed for Sso2522 it has been suggested that Cys-258 may function to protonate the leaving group hydroxyl based upon the orientation of the N-acyl homocysteine lactone within the active site (32). This conclusion is unlikely to be true since this residue is not conserved within those members of the AHS that have been demonstrated to possess lactonase activity (see Figure 7). It appears that the homocysteine lactone is binding in an unproductive orientation in the structure of Sso2522 and this may explain why no turnover is observed for this compound.

Figure 8.

Facial orientations of the amide or esters bonds of substrates or inhibitors in the active sites of Sso2522 (32), dihydroorotase (33), and iso-aspartyl dipeptidase (34) plus the proposed facial selectivity for Dr0930. The indicated face of the trigonal functional group to be hydrolyzed is directed toward the nucleophilic hydroxide in the ligand-bound complexes determined from x-ray crystallography. The bond to be cleaved is written in bold.

Mechanism of Action

A catalytic reaction mechanism may be proposed for the hydrolysis of lactones by Dr0930. In this mechanism the carbonyl oxygen would be polarized by interaction with the β-metal ion. In simple lactones, such as depicted by 11, the si-face of the lactone ring (see Figure 8) would be orientated toward the hydroxide that bridges the two metal ions. Nucleophilic attack by the bridging hydroxide would initiate the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate and transfer of the proton from the hydroxide to Asp-264. The intermediate would collapse with subsequent transfer of the proton to the leaving group alcohol.

Enhancement of Phosphotriesterase Activity in Dr0930

Two approaches were taken in an attempt to enhance the phosphotriesterase activity of Dr0930. The first attempt involved the transplantation of the eight specificity loops from the PTE of P. diminuta for the eight corresponding loops within the active site of Dr0930. The number of residues within each of these eight loops differed between PTE and Dr0930 but the three dimensional position for the starting and ending residues within each of these eight loops is the same between these two proteins (Figure 7) and thus it was anticipated that the chimeric protein would be structurally very similar to PTE. However, the chimeric protein was largely insoluble and the hydrolysis of paraoxon could not be detected with the protein that could be made soluble through refolding. There are thus some rather subtle issues that govern the folding of the chimeric protein that are not well understood. Nevertheless, the construction of rationally placed site-directed mutations within the active site of Dr0930 resulted in the enhancement of the paraoxonase activity by a factor of 16 with only two amino acid changes. These initial results suggest that further improvements in the expression of phosphotriesterase activity within Dr0930 should be possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marco Bocola for insightful discussions and his help in designing the PTE-Dr0930 chimeric protein, Alexander Ehrmann for experimental support and Professor Donald Pettigrew for his help with the ultracentrifugation experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the NIH (GM 071790). PK was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation for a Fellowship for Prospective Researchers (PBZHA-118815). FMR was supported by a Mercator Visiting Professorship at the University of Regensburg funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The X-ray coordinates and structure factors for Dr0930 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB accession code: 3FDK).

Abbreviations: AHS, amidohydrolase superfamily; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; IPTG, isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside; PHP, phosphotriesterase homology protein; AhlA, N-acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Rhodococcus erythropolis; PTE, phosphotriesterase; Sso2552, the lactonase also known as SsoPox from Sulfolobus solfataricus; PPH, putative parathion hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis; ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma emission mass spectrometry.

Because of priority rules the si-face of a thiolactone is equivalent to the re-face of an amide.

Supporting Information Available

The structures of compounds found not to be substrates for Dr0930 (Figure S1) are available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Seibert CM, Raushel FM. Structural and catalytic diversity within the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6383–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi047326v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T, Iwaki H, Fu R, Hasegawa Y, Zhang H, Liu A. α-Amino-β-carboxymuconic-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD) is a new member of the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6628–6634. doi: 10.1021/bi060108c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams L, Nguyen T, Li Y, Porter T, Raushel FM. Uronate isomerase: a nonhydrolytic member of the amidohydrolase superfamily with an ambivalent requirement for a divalent metal ion. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7453–7462. doi: 10.1021/bi060531l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm L, Sander C. An evolutionary treasure: unification of a broad set of amidohydrolases related to urease. Proteins. 1997;28:72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pegg SC-H, Brown S, Ojha S, Seffernick J, Meng EE, Morris JH, Chang PJ, Huang CC, Ferrin TE, Babbitt PC. Leveraging enzyme structure-function relationships for functional inference and experimental design: the structure-function linkage database. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2545–2555. doi: 10.1021/bi052101l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marti-Arbona R, Xu C, Steele S, Weeks A, Kuty GR, Seibert CM, Raushel FM. Annotating enzymes of unknown function: N-formimino-l-glutamate deminase is a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1997–2005. doi: 10.1021/bi0525425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermann JC, Marti-Arbona R, Fedorov AA, Fedorov E, Almo SC, Shoichet BK, Raushel FM. Structure-based activity prediction for an enzyme of unknown function. Nature. 2007;448:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nature05981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen TT, Brown S, Fedorov AA, Fedorov EV, Babbitt PC, Almo SC, Raushel FM. At the periphery of the amidohydrolase superfamily: Bh0493 from Bacillus halodurans catalyzes the isomerization of d-galcutronate to d-tagaturonate. Biochemistry. 2007;47:1194–1206. doi: 10.1021/bi7017738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermann JC, Ghanem E, Li YC, Raushel FM, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. Predicting substrates by docking high-energy intermediates to enzyme structures. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15882–15891. doi: 10.1021/ja065860f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aubert SD, Li Y, Raushel FM. Mechanism for the hydrolysis of organophosphates by the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5705–5715. doi: 10.1021/bi0497805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong SB, Raushel FM. Stereochemical constraints on the substrate specificity of phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16158–16166. doi: 10.1021/bi982204m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afriat L, Roodveldt C, Manco G, Tawfik DS. The latent promiscuity of newly identified microbial lactonases is linked to a recently diverged phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13677–13684. doi: 10.1021/bi061268r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Science. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demeler B. UltraScan, A Comprehensive Data Analysis Software Package for Analytical Ultracentrifugation Experiments. In: Scott DJ, Harding SE, Rowe AJ, editors. Modern Analytical Ultracentrifugation: Techniques and Methods. Royal Society of Chemistry (UK); 2005. pp. 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demeler B. The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Department of Biochemistry; UltraScan version 9.9. A Comprehensive Data Analysis Software Package for Analytical Ultracentrifugation Experiments. http:/www.ultrascan.uthscsa.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demeler B, van Holde KE. Sedimentation velocity analysis of highly heterogeneous systems. Anal. Biochem. 2004;335:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demeler B, Saber H, Hansen JC. Identification and interpretation of complexity in sedimentation velocity boundaries. Biophysical Journal. 1997;72:397–407. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78680-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman E, Wong CH. A pH sensitive colorimetric assay for the high-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors and substrates: a case study using kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:551–555. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, in Methods. In: Carter CWJ, Sweet RM, Abelson JN, Simon MI, editors. Enzymol. New York: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nature Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones AT. Interactive computer graphics: FRODO. Methods Enzymol. 1985;115:157–171. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLAno WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Hattori M, Aoki-Kinoshi,ta KF, Itoh M, Kawashima S, Katayama T, Araki M, Hirakawa M. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM - a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Momany FA, Rone R. Validation of the general-purpose QUANTA(R)3.2/CHARMm(R) force-field. J. Comp. Chem. 1992;13:888–900. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanhooke JL, Benning MM, Raushel FM, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of the zinc-containing phosphotriesterases with the bound substrate analog diethyl 4-methylbenzylphosphonate. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6020–6025. doi: 10.1021/bi960325l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pyrz JW, Sage JT, Debrunner PG, Que L. The interaction of phosphate with uteroferrin: characterization of a reduced uteroferrin-phosphate complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11015–11020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis JC, Averill BA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:4623–4627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watkins LM, Kuo JM, Chen-Goodspeed M, Raushel FM. A combinatorial library for the binuclear metal center of bacterial phosphotriesterase. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 1997;29:553–561. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199712)29:4<553::aid-prot14>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holm L, Sander C. Searching protein structure databases has come of age. Proteins. 1994;19:165–173. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benning MM, Kuo JM, Raushel FM, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of phosphotriesterase: an enzyme capable of detoxifying organophosphate nerve agents. Biochemistry. 33:15001–15007. doi: 10.1021/bi00254a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson CJ, Foo JL, Kim HK, Carr PD, Liu JW, Salem G, Ollis DL. In crystallo capture of a Michaelis complex and product-binding modes of a bacterial phosphotriesterase. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:1189–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elias M, Dupuy J, Merone L, Mandrich L, Porsio E, Moniot M, Roshu D, Lecompte C, Rossi M, Masson P, Manco G, Chabriere E. Structural basis for natural lactonase and promiscuous phosphotriesterase activities. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoden JB, Phillips GN, Neal TN, Raushel FM, Holden HM. Molecular structure of dihydroorotase: a paradigm for catalysis through the use of a binuclear metal center. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6989–6997. doi: 10.1021/bi010682i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marti-Arbona R, Fresquet V, Thoden JB, Davis ML, Holden HM, Raushel FM. Mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by isoaspartyl dipeptidase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7115–7124. doi: 10.1021/bi050008r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall RS, Brown S, Fedorov A, Fedorov L, Babbitt PC, Almo SC, Raushel FM. Structural diversity within the mononuclear and binuclear active sites of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7953–7962. doi: 10.1021/bi700544c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.