Abstract

Protease genes were identified that exhibited increased mRNA levels before and immediately after rupture of the naturally selected, dominant follicle of rhesus macaques at specific intervals after an ovulatory stimulus. Quantitative real-time PCR validation revealed increased mRNA levels for matrix metalloproteinase (MMP1, MMP9, MMP10, and MMP19) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin-like repeats (ADAMTS1, ADAMTS4, ADAMTS9, and ADAMTS15) family members, the cysteine protease cathepsin L (CTSL), the serine protease urokinase-type plasminogen activator (PLAU), and the aspartic acid protease pepsinogen 5 (PGA5). With the exception of MMP9, ADAMTS1, and PGA5, mRNA levels for all other up-regulated proteases increased significantly (P < 0.05) 12 h after an ovulatory human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) bolus. MMP1, -10, and -19; ADAMTS1, -4, and -9; CTSL; PLAU; and PGA5 also exhibited a secondary increase in mRNA levels in 36-h postovulatory follicles. To further determine metalloproteinase involvement in ovulation, vehicle (n = 4) or metalloproteinase inhibitor (GM6001, 0.5 μg/follicle, n = 8) was injected into the preovulatory follicle at the time of hCG administration. Of the eight GM6001-injected follicles, none displayed typical stigmata indicative of ovulation at 72 h after hCG; whereas all four vehicle-injected follicles ovulated. No significant differences in mean luteal progesterone levels or luteal phase length occurred between the two groups. Subsequent histological analysis revealed that vehicle-injected follicles ruptured, whereas GM6001-injected follicles did not, as evidenced by an intact stroma and trapped oocytes (n = 3). These findings demonstrate metalloproteinases are critical for follicle rupture in primates, and blocking their activity would serve as a novel, nonhormonal means to achieve contraception.

After the midcycle LH surge, processes critical for the release of the oocyte from the preovulatory follicle are initiated. The release of the oocyte from the follicle requires highly coordinated events that include the degradation of type IV collagen, laminin, and fibronectin that forms the basement membrane surrounding the follicle as well as the degradation of type I collagen within the follicle wall at the site of rupture (1–5). The degradation and cellular reorganization that takes place also allows for the invasion of newly forming blood vessels into the mural granulosa layer of the follicle (6). Such a high degree of extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and cellular reorganization is associated with increased gelatinase, collagenase, and serine protease activities (1). Furthermore, proteolytic activities are required within the follicle to ensure significant expansion of the intercellular space between cells comprising the cumulus-oocyte complex (7, 8). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that a tightly controlled network of proteolytic activity plays a critical role in ovulation and, thus, fertility.

To date, most studies investigating the role of proteases in ovulation focused primarily on the matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and their inhibitors (i.e. tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases), the plasminogen activators (PA)/plasmin system, as well as certain a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin-like repeats (ADAMTS) family members. Despite the characterization of ovarian MMP, ADAMTS, and PA/plasmin expression and cellular localization, few studies demonstrated a functional role for these proteases in the rodent ovary (9–11). With the exception of ADAMTS1, null mutants generated for several metalloproteinase family members and the PA/plasmin system are without a significant ovarian phenotype (10, 12–15). These findings suggest that there is a functional redundancy that allows for critical ovarian processes when a single protease is deleted, or the proteases that are critical for various aspects of ovarian function have yet to be identified. In support of the latter, only a fraction of the total proteases present within the mouse or human genome have been studied with regard to their role in ovarian function. In fact, a recent in silico analysis led to the annotation of 628 and 533 different proteases in the entire mouse and human genome, respectively (16). Of the 533 human proteases identified, 186 and 176 were classified as metallo and serine proteases, respectively, with a limited subset being analyzed in the primate ovary with regard to possible involvement in follicle rupture.

We set out, therefore, to systematically identify those genes encoding proteases whose expression increases in the primate follicle through the periovulatory interval. Using a recently published rhesus macaque Affymetrix genome microarray database that includes more than 47,000 probe sets (17), the expression of most, if not all, known protease-encoding genes was defined in pre- and postovulatory follicles. Individual, naturally selected follicles were obtained from rhesus macaques undergoing a controlled ovulation (COv) protocol (18) at specific intervals after the administration of an ovulatory bolus of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). The use of this protocol allows for the clamping of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, thereby permitting the development of a single ovulatory follicle as occurs in natural menstrual cycles (18). The resultant array database revealed that metalloproteinase superfamily members, including both MMP and ADAMTS subtypes, were the majority of protease-encoding genes exhibiting increased mRNA levels throughout the rhesus macaque periovulatory interval. Based on this observation, further studies were designed and conducted to test the hypothesis that metalloproteinase activity is critical for primate ovulation.

Materials and Methods

Animal protocols

All protocols were approved by the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A description of the care and housing of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) at the ONPRC was published previously (19). Menstrual cycles of adult, female rhesus monkeys were monitored, and blood samples were collected by saphenous venipuncture daily starting 4 d after the onset of menses until the next menstrual period (20).

Controlled ovulation

Briefly, a COv protocol was started as previously published (17, 18) when morning estradiol (E) levels reached more than 100 pg/ml and less than 120 pg/ml during the mid-to-late follicular phase of natural cycles (typically d 6–13 of cycle). That afternoon (1600 h), a GnRH antagonist (acyline, 0.75 μg/kg; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD) was administered to prevent the occurrence of the spontaneous midcycle gonadotropin surge, along with recombinant human (rh) FSH and rhLH (Repronex, 30 IU each; Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Parsippany, NJ) to support the continued development and maturation of the ovulatory follicle. On the second day, another 30-IU dose of rhFSH and rhLH each and acyline was administered at 0800 h, whereas the gonadotropins were administered again at 1600 h. On the third and final day of the protocol, females received an ovulatory bolus of hCG (Novarel; Ferring Pharmaceuticals; 1000 IU hCG at 0800 h). In some instances, the ovary bearing the ovulatory follicle was removed from anesthetized animals before (0 h) or 12, 24, 36, and 72 h after hCG injection (n = 4–6 per time point). Ovulation generally occurs by 36–44 h after hCG. Ovaries from the 36-h time point were divided into two groups: those with a follicle that had not yet ruptured (36 h-Pre) and those whose follicle possessed an ovulatory stigmata (36 h-Post). The periovulatory follicle was isolated from the ovary as previously described (17).

Intrafollicular injection

Intrafollicular injection was performed on anesthetized animals as previously described (21–23) during a laparotomy to expose the ovary bearing the dominant follicle. The needle on an insulin syringe containing 50 μl solution was inserted through the stroma of the ovary before penetrating the follicular wall. Then, 50 μl follicular fluid was aspirated into the syringe, diluting the injectable by half, before injecting 50 μl of this mixed solution into the follicle. Upon removal of the needle, the follicle was observed to ensure that deflation did not occur. A sequential experimental design was typically employed whereby animals (n = 4) received an intrafollicular injection of vehicle (0.4% dimethylsulfoxide in PBS) in one protocol, and then the broad-spectrum metalloproteinase inhibitor GM6001 (Galardin, 0.5 μg injected/follicle; EMD Biosciences, Gibbstown, NJ) in two additional protocols. After each treatment, animals were permitted to recover for at least one menstrual cycle before starting the next protocol.

Laparoscopic and histological evaluation of follicle rupture

To assess ovulation, animals undergoing various treatment protocols underwent laparoscopy to determine the presence or absence of follicle rupture (protruding stigmata) at 72 h after hCG treatment as reported previously (24). Laparoscopic examination of ovaries is a useful method to determine the extent of late follicle development and to discern whether ovulation has occurred (25). Ovaries with structures (ovulatory stigmata or developing follicles) were compared with contralateral ovaries for size and degree of vasculature differences; surgeries were recorded digitally to compare results in a single analysis. A subset of animals (n = 3 per treatment) were hemiovariectomized for subsequent sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin staining, whereas the remaining animals were kept intact and assessed for circulating progesterone (P) and E levels until menses to monitor luteal function and lifespan, respectively.

Hormone assays

Serum concentrations of P and E were determined by the Endocrine Technologies Support Laboratory at ONPRC using specific electrochemoluminescent assays (IMMULITE 2000; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). LH concentrations were also determined by the Endocrine Technologies Support Laboratory using a specific RIA to ensure that the spontaneous LH surge in animals undergoing a COv protocol had been effectively blocked by the acyline treatment. Previous experiments from this laboratory have shown the ovulatory peak of LH to fall within the 20- to 70-ng/ml range, with serum LH values generally being maintained between 0.5 and 2.0 ng/ml for the remainder of the cycle (data not shown). Based on a conservative estimate, LH levels higher than 5.0 ng/ml were considered indicative of an endogenous LH surge, which did not occur in any of the animals undergoing COv protocols.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from periovulatory follicles, and cDNA was synthesized as previously described (26, 27). Genes encoding proteases chosen for subsequent qPCR analyses were identified from a published DNA microarray database (17) based on the criteria of a significant (P < 0.05) and at least a 2-fold mRNA increase in the follicle after animals received an ovulatory bolus of hCG. Protease gene probe sets included on the Affymetrix Rhesus Macaque Total Genome Array were used to BLAST the rhesus macaque genome sequence to obtain corresponding annotated, full-length cDNA sequences, which were then used to design qPCR primer and TaqMan probes as previously described (26). Sequences of all primers and probes are listed in Supplemental Table 1 (published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Relative levels of target gene expression were normalized to mitochondrial ribosomal protein S10 (MRPS10) levels.

General histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Ovaries obtained by laparoscopy were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin overnight (Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI), dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions (50, 70, and 100%) and stored after being embedded in paraffin. General histology and image capture was performed as previously described (21). IHC was performed on whole ovarian sections (5 μm) that were deparaffinized with xylene and hydrated through a graded series of ethanol. Sections were incubated in PBS before pressure cooker antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Endogenous peroxidase activity was then quenched with a 10-min incubation in 3% H2O2. Sections were placed in a blocking buffer (1.5% normal goat serum in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. With the exception of the ADAMTS9 antibody, which was purchased from Sigma, all other antibodies were obtained from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies recognizing human MMP1 (catalog item ab38925), MMP9 (catalog item ab5707), MMP10 (catalog item ab5708), MMP19 (catalog item ab39002), ADAMTS1 (catalog item ab28284), ADAMTS4 (catalog item ab28285), and ADAMTS15 (catalog item ab28516) were diluted in normal goat serum/PBS to a final concentration of 1.0 μg/ml, whereas ADAMTS9 (catalog item HPA028577) was diluted to a final concentration of 1.5 μg/ml, and incubated with tissue sections at 4 C overnight. Primary antibodies were detected using a biotinylated antirabbit IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and a peroxidase substrate kit (ABC Elite Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Omission of the primary antibody (negative control) was used to determine background levels of staining. The images were captured using an Olympus BX40 microscope equipped with a digital Olympus DP12 camera.

Statistics

For parametric data, ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls tests were performed to detect differences between time points, with the significance level set at P < 0.05, using the SigmaStat software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). For nonparametric data, Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's method tests were performed using SPSS, with a significance level set at P < 0.05. A Student's t test was performed to determine statistical significance (P < 0.05) between P and E levels in animals receiving intrafollicular vehicle or GM6001 injections on a given day of the luteal phase.

Results

Protease mRNA up-regulated in the rhesus monkey follicle after an ovulatory stimulus

Our previously published genome array database of the macaque COv follicle (17) was analyzed to systematically identify those protease genes whose mRNA levels increase in the naturally selected dominant follicle after the administration of an ovulatory bolus of hCG. All genes annotated as encoding proteases that were differentially regulated (P < 0.05 by ANOVA) within follicles isolated before (0 h) or 12, 24, and 36 h [comprised of an unruptured follicle group (36 h-Pre) or a ruptured follicle group (36 h-Post)] after hCG administration were retrieved from the publically accessible Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) array data set GSE22776. In total, 18 protease genes were differentially expressed in the macaque follicle through the periovulatory interval. Of the 18 protease genes, 11 exhibited at least 2-fold higher levels of mRNA at one or more time points after hCG administration and before rupture (Table 1). Of those, eight were metallo family members belonging to the MMP and ADAMTS subfamilies, which includes MMP1, -9, -10, and -19, as well as ADAMTS1, -4, -9, and -15.

Table 1.

Protease-encoding genes exhibiting significantly higher mRNA levels after hCG administration and before follicle rupture as determined by DNA microarray

| Protease | Class | Substratesa |

|---|---|---|

| MMP1 | Metallo | Collagen (I), aggrecan, fibrin, IGFBP, pro-TNFα |

| MMP9 | Metallo | Collagen (I, IV), aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, pro-TNFα/TGFα |

| MMP10 | Metallo | Collagen (IV), aggrecan, elastin, fibronectin, laminin |

| MMP19 | Metallo | Collagen (IV), fibronectin, laminin, nidogen |

| ADAMTS1 | Metallo | Aggrecan, versican |

| ADAMTS4 | Metallo | Aggrecan, brevican |

| ADAMTS9 | Metallo | Aggrecan |

| ADAMTS15 | Metallo | Aggrecan |

| CTSL1 | Cysteine | Broad specificity |

| PGA5 | Aspartic acid | Broad specificity |

| PLAU | Serine | Plasminogen |

Differentially regulated mRNA (P < 0.05, ANOVA) encoding known proteases that increased 2-fold or more in rhesus macaque follicles after hCG administration and before rupture were identified within a previously published DNA microarray study (17). IGFBP, IGF-binding protein.

Substrate specificity for each of the listed proteases as indicated in the MEROPS database (55).

The mRNA of nonmetallo family members that increased in expression after an ovulatory bolus of hCG (Table 1) included genes encoding the cysteine protease cathepsin L (CTSL), the serine type protease urokinase plasminogen activator (PLAU), and the aspartic acid protease pepsinogen A5 (PGA5). The microarray data also revealed that cathepsin C (CTSC) mRNA levels increased after hCG injection, but this gene was not subjected to further investigation because increased expression was observed only after follicle rupture (Supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting a possible role in luteal formation and not ovulation.

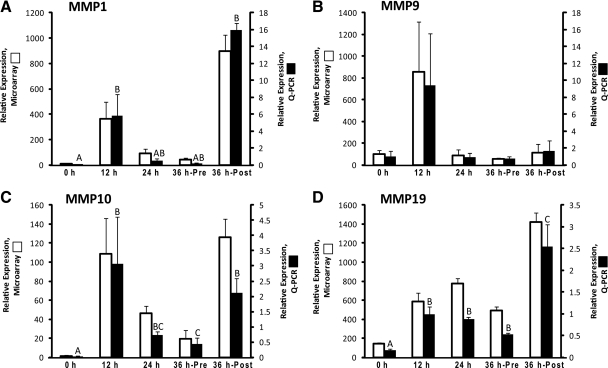

The resultant microarray data revealed a common theme regarding the regulation of MMP1, -9, -10, and -19 mRNA levels, in that expression increased by 12 h after hCG administration (Fig. 1). Validation by qPCR revealed a similar pattern of expression for all four of the MMP genes, although the increase in MMP9 mRNA levels did not reach statistical significance in the 12-h post-hCG group due to a high level of sample-to-sample variability. As determined by qPCR, 1423-, 90-, 9-, and 6-fold increases in mRNA levels were noted for MMP1, -9, -10, and -19, respectively, in the 12-h group relative to 0-h (pre-hCG) follicles. The mRNA levels for MMP1 and MMP9 returned to pre-hCG levels in the 24- and 36-h unruptured follicles (Fig. 1, A and B), whereas MMP19 mRNA levels remained elevated during this time interval (Fig. 1D). MMP10 mRNA levels were intermediate between pre-hCG (0 h) and 12-h post-hCG levels (Fig. 1C) in the unruptured 24- and 36-h post-hCG follicles. MMP1, -10, and -19 mRNA exhibited a secondary increase in expression in the 36-h post-hCG ruptured follicle (Fig. 1, A, C, and D).

Fig. 1.

The relative mRNA expression of MMP family members A, MMP1; B, MMP9; C, MMP10; D, MMP19 in the macaque periovulatory follicle. Follicles were collected at 0 h (before hCG treatment), 12, 24, and 36 h (36 h-Pre, unruptured follicle; 36 h-Post, ruptured follicle) after hCG treatment during a COv protocol. Black bars represent the qPCR quantitation of mRNA levels normalized to MRPS10 RNA (mean ± sem; n = 4–6 per time point). White bars are the microarray evaluation of relative gene expression. Different letters above the qPCR data indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) between the time points.

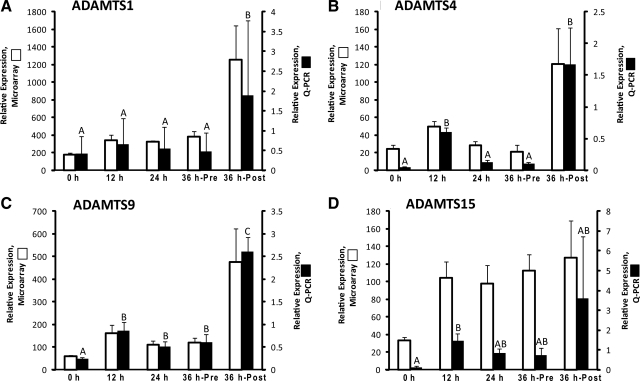

Four ADAMTS-encoding genes, including ADAMTS1, -4, -9, and -15 exhibited a 2-fold or greater increase in mRNA levels in the ovulatory follicle after hCG administration, as determined from the DNA microarray database (Fig. 2). Of these, qPCR validation studies revealed ADAMTS4, -9, and -15 mRNA levels increased 13-, 4-, and 12-fold (P < 0.05), respectively by 12 h after hCG injection, which was followed by a secondary increase in the 36-h ruptured follicle (Fig. 2, B–D). ADAMTS4 mRNA levels returned to pre-hCG levels in the 24- and 36-h preovulatory follicle, whereas ADAMTS9 remained significantly higher during this time period. ADAMTS15 mRNA levels were intermediate between pre-hCG (0-h) and 12-h post-hCG levels in unruptured 24- and 36-h post-hCG follicles. Although ADAMTS1 mRNA levels increased 2-fold by 12 h after hCG administration as determined by DNA microarray, qPCR studies revealed a smaller nonsignificant increase in its expression at this time point (Fig. 2A). A significant increase in expression for ADAMTS1 was observed only by qPCR relative to the 0-h group in 36-h ruptured follicles (4-fold).

Fig. 2.

The relative mRNA expression of ADAMTS metalloproteinase family members. A, ADAMTS1; B, ADAMTS4; C, ADAMTS9; D, ADAMTS15 in the periovulatory follicle of the rhesus monkey. Refer to the legend of Fig. 1 for additional details.

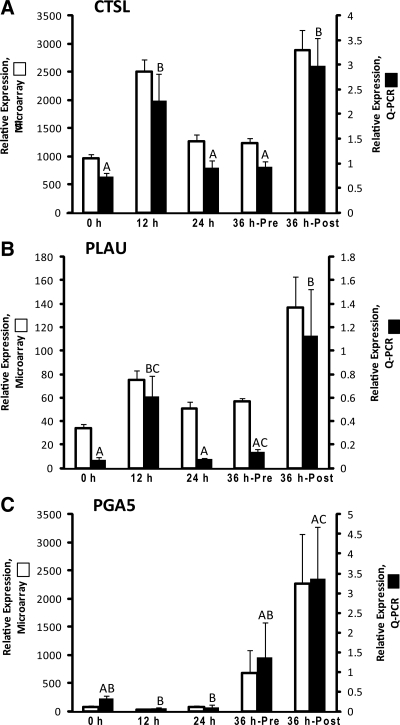

The DNA microarray database revealed increased mRNA levels (2-fold or greater; P < 0.05) for the cysteine protease CTSL, the serine protease PLAU, and the aspartic acid protease PGA5 in the preovulatory follicle after hCG injection and before rupture (Fig. 3). As determined by qPCR, CTSL and PLAU mRNA levels increased 3- and 9-fold, respectively, in the preovulatory follicle by 12 h after hCG injection (Fig. 3, A and B). PGA5 qPCR data revealed that this protease did not change significantly through the first 24 h of the periovulatory interval (Fig. 3C). Although the pattern of expression was similar, PGA5 mRNA levels were not found to be significantly different by qPCR in the unruptured follicle 36 h after hCG injection relative to the 0-h group due to a high degree of intragroup variability. It was not until after rupture (36 h-Post), when a significant (P < 0.05, 10-fold) increase in PGA5 mRNA was noted.

Fig. 3.

The relative mRNA expression of the cysteine protease CTSL (A), the serine protease PLAU (B), and the aspartic acid protease PGA5 (C) in the periovulatory follicle of the rhesus monkey. Refer to the legend of Fig. 1 for additional details.

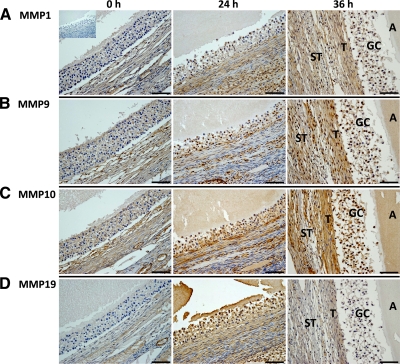

Cellular localization of metalloproteinases in the rhesus macaque ovulatory follicle

To determine whether the metalloproteinases that are up-regulated in the macaque follicle before rupture (e.g. MMP1, -9, -10, and -19; ADAMTS1, -4, -9, and -15) localize to the follicle wall, IHC was performed on ovarian sections obtained from animals undergoing COv protocols before (0 h) and after (24 h; 36-h unruptured follicle) the administration of hCG. For the MMP family members analyzed, an overall theme regarding their expression and localization was noted, primarily that increased staining intensity occurred in the theca and/or stroma cell layer after hCG administration (Fig. 4). MMP1, -9, -10, and -19 exhibited limited staining in the granulosa, theca, and stroma cells associated with the large preovulatory follicle before hCG administration. Increased immunostaining for MMP1 was observed in the adjacent theca and stroma cells at 24 and 36 h after hCG exposure, whereas granulosa cell expression appears to be only marginally elevated at these time points (Fig. 4A). Increased MMP10 and -19 immunolocalization were also observed in granulosa cells 24 h after hCG (Fig. 4, C and D). Whereas MMP10 staining intensity was the same or slightly increased in 36-h post-hCG follicles relative to the 24-h post-hCG samples, MMP19 staining intensity was lower at this time point. MMP9 staining also increased 24 and 36 h after hCG injection, although the level of increase at 24 h was not as pronounced as for MMP1, -10, and -19. MMP9 protein was localized primarily to the granulosa cells and distinct layers of the surrounding theca and stroma (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Protein localization of MMP family members. Panel A, MMP1; panel B, MMP9; panel C, MMP10; panel D, MMP19 in the rhesus macaque follicle before (0 h, left panel) and after (24 h, middle panel; 36-h preovulatory follicles, right panel) injection of an ovulatory bolus of hCG. Scale bar, 50 μm. The inset includes a control section where the primary antibody was excluded. The approximate locations of various ovarian cell types and compartments are indicated in the panels, including granulosa cells (GC), theca cells (T), stroma cells (ST), and the antrum of the periovulatory follicle (A).

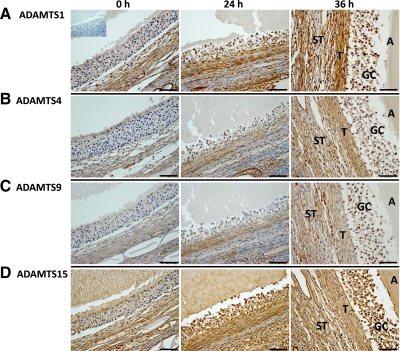

In contrast to the limited degree of staining for the MMP before hCG injection, ADAMTS1 and -15 exhibited a greater basal level of expression in the preovulatory follicle (Fig. 5). For ADAMTS1, significant theca cell expression is present in the pre- and post-hCG samples, whereas the granulosa cells stained much more intensely 24 and 36 h after hCG administration (Fig. 5A). ADAMTS4 and -9 exhibited progressively greater staining 24 and 36 h after hCG injection primarily in the theca and stroma (Fig. 5, B and C). ADAMTS15 immunostaining was associated with granulosa, theca, and adjacent stroma cells, with heightened levels appearing in these cells types after hCG injection (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Protein localization of ADAMTS family members Panel A, ADAMTS1; panel B, ADAMTS4; panel C, ADAMTS9; panel D, ADAMTS15 in the rhesus macaque follicle before (0 h, left panel) and after (24 h, middle panel; 36-h preovulatory follicles, right panel) injection of an ovulatory bolus of hCG. Refer to the legend of Fig. 4 for additional details.

Intrafollicular inhibition of metalloproteinases prevents follicle rupture but not subsequent luteal P or E synthesis

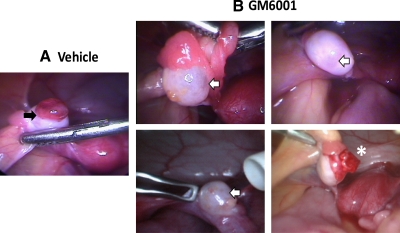

Because eight of the 11 proteases up-regulated after hCG administration and before follicle rupture are MMP and ADAMTS family members, studies were performed to assess the potential for a broad-spectrum metalloproteinase inhibitor (GM6001) to block ovulation in rhesus macaques. During COv protocols, animals received either vehicle (0.4% dimethylsulfoxide in PBS) or GM6001 (0.5 μg/follicle) at the time that hCG was administered to initiate periovulatory events. At 72 h after hCG (28–36 h after the time of expected ovulation), laparoscopy was performed to check for the presence or absence of a protruding stigmata as an indicator of follicle rupture. In this experimental scheme, each animal (n = 4) served as its own control whereby vehicle was injected first and was followed by two subsequent intrafollicular GM6001 injections (n = 8). Intrafollicular injection of vehicle resulted in ovulation in all four animals as evidenced by a stigmata present on the ovary at 72 h after hCG administration (Fig. 6A). In contrast, of the subsequent eight intrafollicular GM6001 injections, six failed to display a stigmata indicative of follicle rupture, whereas two possessed abnormal stigmata that were inconclusive with regard to whether the follicles actually ruptured (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Representative laparoscopic images of follicular rupture 72 h after hCG in macaques receiving an intrafollicular injection of vehicle (A) or 0.5 μg of the metalloproteinase inhibitor GM6001 (B). Intrafollicular injection of vehicle or GM6001 occurred at the time of hCG administration. Stigmata formation after injection of vehicle is indicated by a solid arrow, whereas unruptured follicles and an abnormal, presumed stigmata are denoted by a white arrow and asterisk, respectively.

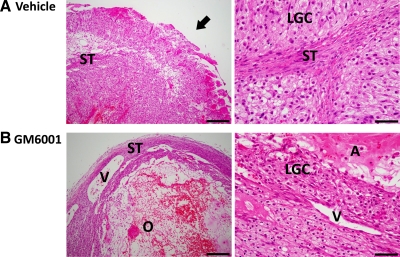

In a subset of animals (n = 3), ovaries bearing vehicle- and GM6001-injected follicles were removed 72 h after hCG injection, serially sectioned, and analyzed by microscopy to further establish the effects of metalloproteinase activity on follicle rupture. All vehicle-injected follicles ovulated as evidenced by a clear ovulatory canal and rupture site (Fig. 7A), whereas GM6001-injected follicles possessed an intact stroma/follicle wall (Fig. 7B). In GM6001-injected follicles, the remnants of a trapped, degenerating oocyte were clearly visible. Moreover, the vehicle controls exhibited a normal luteal morphology consisting of the infolding and invagination of stromal and theca cells that is typically observed in the developing primate corpus luteum (Fig. 7A). In contrast, GM6001-injected follicles luteinized without the usual reorganization, such that the presumptive granulosa-lutein cells are distributed concentrically around the center of the unruptured follicle (Fig. 7B). The unruptured follicles that arise after the inhibition of metalloproteinase activity do not appear to persist chronically because laparoscopic evaluations revealed normal-appearing ovaries in subsequent cycles.

Fig. 7.

Representative histological evaluation of follicle rupture from serial-sectioned ovaries 72 h after vehicle (panel A) and 0.5 μg GM6001 (panel B) injection. A discontinuous stroma (ST) and an ovulatory canal (arrow) were evident in each vehicle-treated follicle (panel A, left) with no evidence of an oocyte. A trapped oocyte (O) as well as intact blood vessels (V) and stroma overlaying the unruptured follicle were observed after GM6001 injection (panel B, left). The corpus luteum formed from the vehicle-injected follicle (panel A, right) displayed the typical compartmentalization of presumptive lutein-granulosa cells (LGC) and small luteal/stromal cells (ST), whereas the GM6001-injected follicle possessed LGC that surrounded an intact antrum (A) (panel B, right). Scale bar, 200 μm (left panels) and 50 μm (right panels).

Because metalloproteinase inhibitor injection resulted in the development of atypical luteinizing unruptured follicles, animals were subsequently monitored for circulating P and E levels as well as the first day of menses to evaluate GM6001 effects on luteal function and lifespan, respectively (n = 4 per group). No significant differences were noted for mean luteal phase P and E levels between the vehicle-injected and metalloproteinase inhibitor-injected groups on any of the days analyzed after hCG through menses (Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3). Mean peak P levels were not significantly different at 3.2 ± 0.3 (mean ± sem) and 3.2 ± 1.1 ng/ml in vehicle and GM6001 groups, respectively. Peak E levels midluteal phase were also not significantly different between the vehicle and GM6001 groups (97.5 ± 27.9 vs. 87.8 ± 9.7 pg/ml, respectively). Luteal phase length was slightly longer in the vehicle-treated group (mean ± sem = 15.8 ± 2.2 d) relative to the GM6001-injected group (mean ± sem =14.5 ± 2.9 d), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

The COv protocol offers the unique opportunity to study and manipulate the naturally selected dominant follicle at defined intervals before and after exposure to an ovulatory gonadotropin stimulus in rhesus macaques (18). Therefore, it allows for the analysis of molecular and cellular processes critical for ovulation in the primate preovulatory follicle. Using this protocol, a recent DNA microarray study performed by our laboratory was able to distinguish changes in gene expression within each of the different follicular compartments (e.g. theca, mural granulosa cells, cumulus granulosa cells, and oocytes) (17). As summarized in this analysis, the resultant database provides valuable insight into the coordinated regulation of protease gene expression as the follicle prepares to rupture in response to an ovulatory stimulus. Metalloproteinase superfamily members, including both MMP and ADAMTS subtypes, represented the majority of the protease-encoding genes whose mRNA levels increased in the rhesus macaque follicle through the periovulatory interval. Also, mRNA levels for a few nonmetalloproteinases, such as CTSL, PLAU, and PGA5, increased after an ovulatory stimulus.

Based on the microarray data, MMP1, -9, -10, and -19 mRNA levels peaked 12 h after hCG administration, with MMP1, -10, and -19 exhibiting a secondary rise after ovulation. A similar mRNA expression profile was noted by qPCR for these genes, except the mRNA increase for MMP9 at 12 h after hCG did not reach statistical significance due to a high level of sample-to-sample variability. In comparing our findings with results from studies involving various animal models, species-specific similarities and differences exist with regard to the regulation of individual MMP mRNA types and levels (1, 28–30). For example, similarities between the rat and macaque follicle include increased mRNA levels for MMP1 and -19 after an ovulatory stimulus, whereas MMP9 and MMP19 mRNA levels increase in the mouse and macaque ovary through the periovulatory interval. A notable difference includes increased MMP10 mRNA levels in the rhesus macaque follicle, which has not been reported in other species. Moreover, MMP2, -13, and -14 mRNA levels increase in rodent ovaries after an ovulatory stimulus (31) but remain unchanged in the rhesus macaque follicle. In the rhesus macaque follicle, MMP2 mRNA levels were high but did not vary through the periovulatory period (data not shown). Other examples of species-specific differences in the regulation of protease gene expression include a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17) mRNA, which was reported to increase after gonadotropin treatment of porcine cumulus cells (32), and serine protease 35 (PRSS35) mRNA, which increased more than 4-fold in the mouse ovary after hCG administration (33). In the rhesus macaque follicle, mRNA levels did not increase for either ADAM17 or PRSS35 through the periovulatory interval.

Similar to the MMP family members, levels of ADAMTS4, -9 and -15 mRNA increased in the rhesus macaque follicle 12 h after hCG administration, with a second increase occurring after ovulation. ADAMTS1 mRNA expression increased significantly only after ovulation, suggesting an important role of this ADAMTS family member in luteal development. These data are in agreement with our previous results demonstrating ADAMTS1 mRNA is highest in the developing rhesus monkey corpus luteum, where its levels are regulated by LH (34). In contrast, a recent report proposed ADAMTS1 serves as a crucial ovulatory gene as well as a cumulus marker for fertilization capacity in humans (35). ADAMTS1 mRNA and protein were also found in rat and bovine follicles preceding and after ovulation, suggesting a role in follicle rupture and early luteal development in these species (36–39). In rodents, ADAMTS1 mRNA is strongly induced in mural granulosa cells after an ovulatory stimulus (36, 37, 40), with this effect being dependent upon P receptor signaling (40). Similar to a reported increase in ADAMTS4 mRNA levels in the mouse ovary after an ovulatory stimulus (41), ADAMTS4 mRNA expression increased in the macaque follicle by 12 h after hCG administration. Of the mRNA encoding several ADAMTS family members (e.g. ADAMTS1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -7, -8, and -9) in bovine preovulatory follicles (39), only ADAMTS9 exhibited a comparable preovulatory rise in expression in the rhesus macaque follicle. To our knowledge, however, this is the first study in any species showing increased ADAMTS15 mRNA in the preovulatory follicle after hCG stimulation.

Two nonmetalloproteinases, CTSL and PLAU, also possessed a similar pattern of gene expression whereby mRNA levels peaked in the unruptured follicle 12 h after hCG administration and then exhibited a secondary rise after ovulation. Notably, CTSL was previously shown to be induced in granulosa cells of growing follicles by gonadotropins, with peak mRNA levels observed after the LH surge (37). Through the use of P receptor-null mutants, increased CTSL mRNA in the periovulatory interval was demonstrated to be a P-dependent effect (37). PLAU has been proposed to play an important role in ovulation because it can activate MMP at the cell surface (42). However, in studies involving PLAU-deficient mice, as well as in plasminogen-null mutants, only minimal effects on ovulation were observed (13). Surprisingly, an increase in aspartic acid protease PGA5 mRNA was also observed in the rhesus macaque follicle just before and after ovulation (36 h after hCG administration). Members of this protease family are critical for digestive tract function and highly expressed in the stomach (43). The only previous studies reporting pepsinogen expression in the ovary was in women under pathological circumstances (e.g. epithelial ovarian carcinomas) (44, 45). Whereas the 12-h increase in protease mRNA levels, including both metallo and nonmetallo family members, is likely related to events critical for follicle rupture, their postovulatory increase possibly plays a role in the ECM and cellular reorganization that occurs during luteal development.

The extensive remodeling of the ECM before ovulation requires the degradation of laminin, fibronectin, type IV collagen, and proteoglycans that form the basement membrane surrounding the follicle, as well as the type I collagen within the follicle wall at the site of rupture (1–5). The metalloproteinases identified in the present study, whose mRNA increases before follicle rupture in the macaque, localized to areas possessing such ECM components that must be degraded for ovulation. The immunostaining intensity for MMP1, -9, -10, and -19 appeared to increase in the primate preovulatory follicle after an ovulatory hCG stimulus, primarily in the theca and/or the surrounding stroma cells. ADAMTS1, -4, -9, and -15 also exhibited increased expression after the hCG stimulus, but their levels in the pre-hCG follicle were higher in comparison with MMP family members. The cellular localization for these ADAMTS family members appeared greatest within the stroma cells as well as the theca cells that are adjacent to the granulosa cells and, thus, the basement membrane that separates the two compartments. No preferential immunolocalization of the individual MMP or ADAMTS family members was noted at the apex of the follicle (data not shown), unlike that documented by in situ zymography in the rodent follicle before rupture (46). This difference may be due to the inability of the antibodies used in this study to distinguish between inactive and active forms of the individual enzymes. Additional studies are required in macaque preovulatory follicles to determine whether increased areas of enzyme activity are also found in the primate ovary at the site of rupture.

Whether the hCG-inducible proteases identified in the present study are required for follicle rupture, either individually or together, remains unknown. According to gene knockout studies, multiple proteases may be involved because mice lacking a single enzyme do not exhibit impaired ovarian function. For example, null mutants generated for MMP2, -3, -7, -9, -11, and -19 do not exhibit an overt ovarian phenotype (10, 12–15). In addition, oocyte release from the follicle as well as fertilization in the oviduct are impaired but not abolished in ADAMTS1-null mutant mice (7, 10, 47), which may be related to its involvement in the cumulus-oocyte expansion process (7). Alternatively, it is possible that individual systemic gene deletions may be compensated by the presence of other metalloproteinase family members, requiring future generation of ovary-specific metalloproteinase knockouts. As a third possibility, key proteases critical for primate ovulation have yet to be defined. In support of this latter hypothesis, PLAU knockout mice treated with GM6001 to additionally inhibit metalloproteinase activity ovulated normally (48). Yet in sheep, intrafollicular injection of a MMP2-neutralizing antibody prevented follicle rupture (49). Therefore, in the present study, to determine metalloproteinase involvement in the rupture of the macaque follicle, GM6001 was injected directly into the naturally selected preovulatory follicle. We have used this intrafollicular injection protocol to successfully interrogate the role of a number of processes in primate ovulation, whereby the administration of different vehicles alone does not interfere with timely rupture (21–23). Laparoscopic evaluation of the ovaries 28–36 h after the anticipated time of rupture (72 h after hCG injection) revealed that intrafollicular administration of GM6001 typically inhibited follicle rupture. Of the eight GM6001-injected follicles, six displayed no visible stigmata, and the remaining two possessed abnormal stigmata that were difficult to determine whether the follicles actually ruptured. Furthermore, conclusive findings were obtained from the analysis of serial sections of follicles obtained 72 h after hCG, where it was noted that GM6001-injected follicles possessed intact follicle walls and trapped degenerating oocytes. Thus, these results support the idea that metalloproteinase activity is critical for ovulation in primates and that the mRNA encoding nonmetalloproteinase family members that increase after hCG administration are not capable of promoting follicle rupture on their own.

Despite blocking ovulation, luteinization occurred because no significant differences in luteal P levels or luteal phase length were observed after intrafollicular vehicle or GM6001 injection. However, an abnormal distribution of luteinizing cells was observed in the GM6001-injected follicles in comparison with the normal-appearing CL formed from the vehicle-injected follicle removed 72 h after hCG administration. The former had large luteal cells that were arranged in a concentric distribution surrounding the retained antral cavity of the unruptured follicle. These results suggest that metalloproteinase activity is required for the cellular reorganization that leads to the development of the typical primate corpus luteum but that such tissue remodeling and cellular redistribution are not crucial for steroidogenesis per se. Moreover, laparoscopic evaluations revealed normal-appearing ovaries in subsequent cycles, indicating that these structures (luteinized unruptured follicles) do not persist. The proposed involvement of metalloproteinases during peak luteal function and luteolysis remains to be determined (27, 50), because the broad-spectrum inhibitor was administered only once before ovulation and would not likely be present throughout the entirety of the luteal phase.

The mechanisms controlling the activity of individual ovarian proteases extend beyond their regulation at the level of transcription. In fact, metalloproteinases are well known to be regulated by posttranslational mechanisms involving the removal of an inhibitory domain leading to active enzymes or the association with endogenous inhibitors (e.g. tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases) that block activity (51). Although posttranscriptional aspects of metalloproteinase activity are likely important in the periovulatory follicle and require further investigation, the results from the present study provide insight into the likely candidates that are critical for initiating a complex proteolytic cascade that ultimately leads to follicle rupture.

In addition to their well-known role in degrading ECM proteins, metalloproteinases also allow for the release of growth factors from the plasma membrane of cells. For example, members of the ADAM family have been shown to regulate cytokine/growth factor action by controlling their release from their cellular site of synthesis. ADAM17 has been implicated in the proteolytic release of EGF-like factors (e.g. amphiregulin, epiregulin, and betacellulin) from granulosa cells after an ovulatory stimulus (32), which in turn are critical for mouse ovulation, cumulus-oocyte expansion, and oocyte maturation (52–54). Therefore, the effects of a broad-range MMP inhibitor in the rhesus macaque follicle may also include blocking EGF receptor-dependent regulation of cumulus expansion, reinitiation of meiosis, and possibly follicle rupture. Future studies are required to discern the direct actions of metalloproteinases vs. those of EGF receptor signaling in the primate ovulatory follicle.

In summary, this study details for the first time a systematic genomic characterization of proteases whose mRNA levels increase in the naturally selected primate follicle after an ovulatory stimulus, the majority of which belong to the MMP and ADAMTS metalloproteinase families. Moreover, intrafollicular administration of a broad-spectrum metalloproteinase inhibitor blocked ovulation in the primate ovary without altering either luteal function or lifespan. Therefore, this study provides support for considering metalloproteinases as potential novel nonhormonal targets for the regulation of fertility in women. Future studies are planned with more specific metalloproteinase inhibitors or an intrafollicular gene knockdown approach to determine whether one or a select few of these proteases are critical for follicle rupture in the primate ovary.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the expert contributions of the animal care staff and surgical services unit of the Division of Animal Resources and the outstanding technical support of the Endocrine Services and Technology Laboratory at ONPRC.

This work was supported by Grants U54 HD55744 (to J.D.H. and R.L.S.), R01 HD42000 (to J.D.H.), and RR000163 (to J.D.H. and R.L.S.). A Lalor Fellowship supported M.C.P., and S.T.B. was supported through a grant from the Murdock Charitable Trust's Partners in Science program.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ADAM17

- A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17

- ADAMTS

- a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin-like repeats

- COv

- controlled ovulation

- CTSL

- cathepsin L

- E

- estradiol

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- P

- progesterone

- PA

- plasminogen activator

- PGA5

- pepsinogen A5

- PLAU

- urokinase plasminogen activator

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- rh

- recombinant human.

References

- 1. Curry TE, Jr, Osteen KG. 2003. The matrix metalloproteinase system: changes, regulation, and impact throughout the ovarian and uterine reproductive cycle. Endocr Rev 24:428–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morales TI, Woessner JF, Jr, Marsh JM, LeMaire WJ. 1983. Collagen, collagenase and collagenolytic activity in rat Graafian follicles during follicular growth and ovulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 756:119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fukumoto M, Yajima Y, Okamura H, Midorikawa O. 1981. Collagenolytic enzyme activity in human ovary: an ovulatory enzyme system. Fertil Steril 36:746–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Espey LL. 1976. The distribution of collagenous connective tissue in rat ovarian follicles. Biol Reprod 14:502–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Espey LL. 1967. Ultrastructure of the apex of the rabbit graafian follicle during the ovulatory process. Endocrinology 81:267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hazzard TM, Stouffer RL. 2000. Angiogenesis in ovarian follicular and luteal development. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 14:883–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown HM, Dunning KR, Robker RL, Boerboom D, Pritchard M, Lane M, Russell DL. 2010. ADAMTS1 cleavage of versican mediates essential structural remodeling of the ovarian follicle and cumulus-oocyte matrix during ovulation in mice. Biol Reprod 83:549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Alessandris C, Canipari R, Di Giacomo M, Epifano O, Camaioni A, Siracusa G, Salustri A. 2001. Control of mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex integrity before and after ovulation: plasminogen activator synthesis and matrix degradation. Endocrinology 142:3033–3040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ny T, Wahlberg P, Brändström IJ. 2002. Matrix remodeling in the ovary: regulation and functional role of the plasminogen activator and matrix metalloproteinase systems. Mol Cell Endocrinol 187:29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shindo T, Kurihara H, Kuno K, Yokoyama H, Wada T, Kurihara Y, Imai T, Wang Y, Ogata M, Nishimatsu H, Moriyama N, Oh-hashi Y, Morita H, Ishikawa T, Nagai R, Yazaki Y, Matsushima K. 2000. ADAMTS-1: a metalloproteinase-disintegrin essential for normal growth, fertility, and organ morphology and function. J Clin Invest 105:1345–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leonardsson G, Peng XR, Liu K, Nordström L, Carmeliet P, Mulligan R, Collen D, Ny T. 1995. Ovulation efficiency is reduced in mice that lack plasminogen activator gene function: functional redundancy among physiological plasminogen activators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:12446–12450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. 2001. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 17:463–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ny A, Leonardsson G, Hägglund AC, Hägglöf P, Ploplis VA, Carmeliet P, Ny T. 1999. Ovulation in plasminogen-deficient mice. Endocrinology 140:5030–5035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang YY, Bach ME, Lipp HP, Zhuo M, Wolfer DP, Hawkins RD, Schoonjans L, Kandel ER, Godfraind JM, Mulligan R, Collen D, Carmeliet P. 1996. Mice lacking the gene encoding tissue-type plasminogen activator show a selective interference with late-phase long-term potentiation in both Schaffer collateral and mossy fiber pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8699–8704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carmeliet P, Schoonjans L, Kieckens L, Ream B, Degen J, Bronson R, De Vos R, van den Oord JJ, Collen D, Mulligan RC. 1994. Physiological consequences of loss of plasminogen activator gene function in mice. Nature 368:419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Overall CM, López-Otín C. 2003. Human and mouse proteases: a comparative genomic approach. Nat Rev Genet 4:544–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu F, Stouffer RL, Müller J, Hennebold JD, Wright JW, Bahar A, Leder G, Peters M, Thorne M, Sims M, Wintermantel T, Lindenthal B. 2011. Dynamics of the transcriptome in the primate ovulatory follicle. Mol Hum Reprod 17:152–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Young KA, Chaffin CL, Molskness TA, Stouffer RL. 2003. Controlled ovulation of the dominant follicle: a critical role for LH in the late follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod 18:2257–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolf DP, Thomson JA, Zelinski-Wooten MB, Stouffer RL. 1990. In vitro fertilization-embryo transfer in nonhuman primates: the technique and its applications. Mol Reprod Dev 27:261–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duffy DM, Chaffin CL, Stouffer RL. 2000. Expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the rhesus monkey corpus luteum during the menstrual cycle: regulation by luteinizing hormone and progesterone. Endocrinology 141:1711–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu F, Stouffer RL. 2005. Local delivery of angiopoietin-2 into the preovulatory follicle terminates the menstrual cycle in rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod 72:1352–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duffy DM, Stouffer RL. 2002. Follicular administration of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor can prevent oocyte release without alteration of normal luteal function in rhesus monkeys. Hum Reprod 17:2825–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hazzard TM, Rohan RM, Molskness TA, Fanton JW, D'Amato RJ, Stouffer RL. 2002. Injection of antiangiogenic agents into the macaque preovulatory follicle: disruption of corpus luteum development and function. Endocrine 17:199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hibbert ML, Stouffer RL, Wolf DP, Zelinski-Wooten MB. 1996. Midcycle administration of a progesterone synthesis inhibitor prevents ovulation in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:1897–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rawson JM, Dukelow WR. 1973. Observation of ovulation in Macaca fascicularis. J Reprod Fertil 34:187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bogan RL, Murphy MJ, Stouffer RL, Hennebold JD. 2008. Systematic determination of differential gene expression in the primate corpus luteum during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Mol Endocrinol 22:1260–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Young KA, Hennebold JD, Stouffer RL. 2002. Dynamic expression of mRNAs and proteins for matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in the primate corpus luteum during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod 8:833–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jo M, Curry TE., Jr 2004. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-19 messenger RNA expression in the rat ovary. Biol Reprod 71:1796–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balbín M, Fueyo A, López JM, Díez-Itza I, Velasco G, López-Otín C. 1996. Expression of collagenase-3 in the rat ovary during the ovulatory process. J Endocrinol 149:405–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reich R, Daphna-Iken D, Chun SY, Popliker M, Slager R, Adelmann-Grill BC, Tsafriri A. 1991. Preovulatory changes in ovarian expression of collagenases and tissue metalloproteinase inhibitor messenger ribonucleic acid: role of eicosanoids. Endocrinology 129:1869–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hägglund AC, Ny A, Leonardsson G, Ny T. 1999. Regulation and localization of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in the mouse ovary during gonadotropin-induced ovulation. Endocrinology 140:4351–4358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamashita Y, Kawashima I, Yanai Y, Nishibori M, Richards JS, Shimada M. 2007. Hormone-induced expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme/A disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 impacts porcine cumulus cell oocyte complex expansion and meiotic maturation via ligand activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Endocrinology 148:6164–6175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miyakoshi K, Murphy MJ, Yeoman RR, Mitra S, Dubay CJ, Hennebold JD. 2006. The identification of novel ovarian proteases through the use of genomic and bioinformatic methodologies. Biol Reprod 75:823–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Young KA, Tumlinson B, Stouffer RL. 2004. ADAMTS-1/METH-1 and TIMP-3 expression in the primate corpus luteum: divergent patterns and stage-dependent regulation during the natural menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod 10:559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yung Y, Maman E, Konopnicki S, Cohen B, Brengauz M, Lojkin I, Dal Canto M, Fadini R, Dor J, Hourvitz A. 2010. ADAMTS-1: a new human ovulatory gene and a cumulus marker for fertilization capacity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 328:104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Espey LL, Yoshioka S, Russell DL, Robker RL, Fujii S, Richards JS. 2000. Ovarian expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs during ovulation in the gonadotropin-primed immature rat. Biol Reprod 62:1090–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robker RL, Russell DL, Espey LL, Lydon JP, O'Malley BW, Richards JS. 2000. Progesterone-regulated genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4689–4694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russell DL, Doyle KM, Ochsner SA, Sandy JD, Richards JS. 2003. Processing and localization of ADAMTS-1 and proteolytic cleavage of versican during cumulus matrix expansion and ovulation. J Biol Chem 278:42330–42339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Madan P, Bridges PJ, Komar CM, Beristain AG, Rajamahendran R, Fortune JE, MacCalman CD. 2003. Expression of messenger RNA for ADAMTS subtypes changes in the periovulatory follicle after the gonadotropin surge and during luteal development and regression in cattle. Biol Reprod 69:1506–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Doyle KM, Russell DL, Sriraman V, Richards JS. 2004. Coordinate transcription of the ADAMTS-1 gene by luteinizing hormone and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 18:2463–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Richards JS, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Teuling E, Lo Y, Boerboom D, Falender AE, Doyle KH, LeBaron RG, Thompson V, Sandy JD. 2005. Regulated expression of ADAMTS family members in follicles and cumulus oocyte complexes: evidence for specific and redundant patterns during ovulation. Biol Reprod 72:1241–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murphy G, Stanton H, Cowell S, Butler G, Knäuper V, Atkinson S, Gavrilovic J. 1999. Mechanisms for pro matrix metalloproteinase activation. APMIS 107:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gritti I, Banfi G, Roi GS. 2000. Pepsinogens: physiology, pharmacology pathophysiology and exercise. Pharmacol Res 41:265–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rojo JV, Merino AM, González LO, Vizoso F. 2002. Expression and clinical significance of pepsinogen C in epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 104:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hirsch-Marie H, Bara J, Loisillier F, Burtin P, Bachimont J, van Eggenpoel MJ. 1978. Evidence of pepsinogens in ovarian tumors. Eur J Cancer 14:593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Curry TE, Jr, Song L, Wheeler SE. 2001. Cellular localization of gelatinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases during follicular growth, ovulation, and early luteal formation in the rat. Biol Reprod 65:855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mittaz L, Russell DL, Wilson T, Brasted M, Tkalcevic J, Salamonsen LA, Hertzog PJ, Pritchard MA. 2004. Adamts-1 is essential for the development and function of the urogenital system. Biol Reprod 70:1096–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu K, Wahlberg P, Leonardsson G, Hägglund AC, Ny A, Bodén I, Wibom C, Lund LR, Ny T. 2006. Successful ovulation in plasminogen-deficient mice treated with the broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor galardin. Dev Biol 295:615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gottsch ML, Van Kirk EA, Murdoch WJ. 2002. Role of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in the ovulatory folliculo-luteal transition of ewes. Reproduction 124:347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Young KA, Stouffer RL. 2004. Gonadotropin and steroid regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous tissue inhibitors in the developed corpus luteum of the rhesus monkey during the menstrual cycle. Biol Reprod 70:244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brew K, Nagase H. 2010. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): an ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803:55–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Park JY, Su YQ, Ariga M, Law E, Jin SL, Conti M. 2004. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. Science 303:682–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Panigone S, Hsieh M, Fu M, Persani L, Conti M. 2008. Luteinizing hormone signaling in preovulatory follicles involves early activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Mol Endocrinol 22:924–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ashkenazi H, Cao X, Motola S, Popliker M, Conti M, Tsafriri A. 2005. Epidermal growth factor family members: endogenous mediators of the ovulatory response. Endocrinology 146:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. 2010. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D227–D233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]