Abstract

A series of octadentate ligands featuring the 2-hydroxyisophthalamide (IAM) antenna chromophore (to sensitize Tb(III) and Eu(III) luminescence) has been prepared and characterized. The length of the alkyl amine scaffold that links the four IAM moieties has been varied in order to investigate the effect of the ligand backbone on the stability and photophysical properties of the Ln(III) complexes. The amine backbones utilized in this study are N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-ethane-1,2-diamine [H(2,2)-], N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-propane-1,3-diamine [H(3,2)-] and N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-butane-1,4-diamine [H(4,2)-]. These ligands also incorporate methoxyethylene [MOE] groups on each of the IAM chromophores to increase their water solubility. The aqueous ligand protonation constants and Tb(III) and Eu(III) formation constants were determined from solution thermodynamic studies. The resulting values indicate that at physiological pH, the Eu(III) and Tb(III) complexes of H(2,2)-IAM-MOE and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE are sufficiently stable to prevent dissociation at nanomolar concentrations. The photophysical measurements for the Tb(III) complexes gave overall quantum yield values of 0.56, 0.39, and 0.52 respectively for the complexes with H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, H(3,2)-IAM-MOE and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, while the corresponding Eu(III) complexes displayed significantly weaker luminescence, with quantum yield values of 0.0014, 0.0015, and 0.0058, respectively. Analysis of the steady state Eu(III) emission spectra provides insight into the solution symmetries of the complexes. The combined solubility, stability and photophysical performance of the Tb(III) complexes in particular make them well suited to serve as the luminescent reporter group in high sensitivity time-resolved fluoroimmunoassays.

Introduction

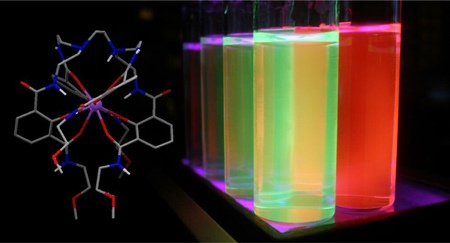

In recent years, interest in highly emissive lanthanide complexes with good aqueous stability has grown considerably, since their long-lived luminescence facilitates their use in time-resolved homogeneous fluoroimmunoassays.1–5 We have reported the development of a new class of these luminescent lanthanide complexes, based on ligands incorporating the 2-hydroxyisophthalamide (IAM) chromophore as a chelating group.6–8 These complexes, formed with several lanthanide cations, are highly luminescent due to a combination of very efficient ligand to lanthanide energy transfer and effective protection of the metal ion from sources of non-radiative deactivation, such as water coordinated to the metal center. The quantum yields reported for the Tb(III) complexes remain some of the highest values described in the literature for lanthanide complexes that are stable in aqueous solution at physiological pH, in the absence of external augmentation agents such as micelles or fluoride. For these reasons, derivatives of these complexes have recently been commercialized and utilized as luminescent probes for high sensitivity homogeneous time-resolved immunoassays.9,10

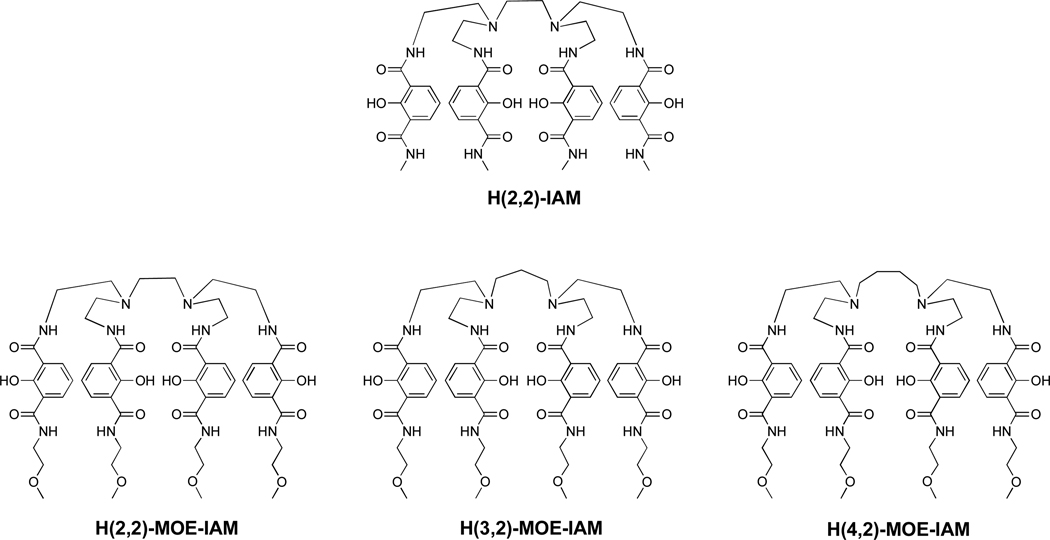

The solubility of the complexes initially described in the literature was too low to allow for detailed stability analyses of the Ln(III) complexes using solution thermodynamic techniques. To overcome this limitation, we have designed a series of octadentate ligands incorporating a methoxyethylene (MOE) amide group in the 6-position of the IAM ring in order to improve the solubility of the ligands and their Ln(III) complexes, since these groups have been previously shown to increase solubility in aqueous solution.11 Concurrently, we have investigated the effect of altering the length of the central alkylamine backbone that connects the four chelating IAM units (Figure 1) with regard to changing the stability and photophysical properties of the Ln(III) complexes. We report here the three new ligands, and the stability and photophysical properties of these ligands in complex with Eu(III) and Tb(III), which facilitates the use of this family of compounds in homogeneous time-resolved fluoroimmunoassays.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of H(2,2)-IAM (top) and monoethylene glycol (MOE)-containing analogs with varied backbones (bottom).

Experimental

General

All chemicals were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Flash silica gel chromatography was performed using Merck 40–70 mesh silica gel. NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature on either Bruker AM-300 or DRX-500 spectrometers operating at 300 (75) MHz and 500 (125) MHz for 1H (or 13C) respectively. Chemical shifts for 1H (or 13C) spectra are reported in ppm relative to the residual solvent resonances, taken as δ 7.26 (δ 77.0) and δ 2.49 (δ 39.5) respectively for CDCl3 and (CD3)2SO. The NMR and mass spectra and elemental analyses were performed at the corresponding analytical services of the College of Chemistry, UC Berkeley. The ligand structures and synthetic procedures are summarized in Scheme 1.

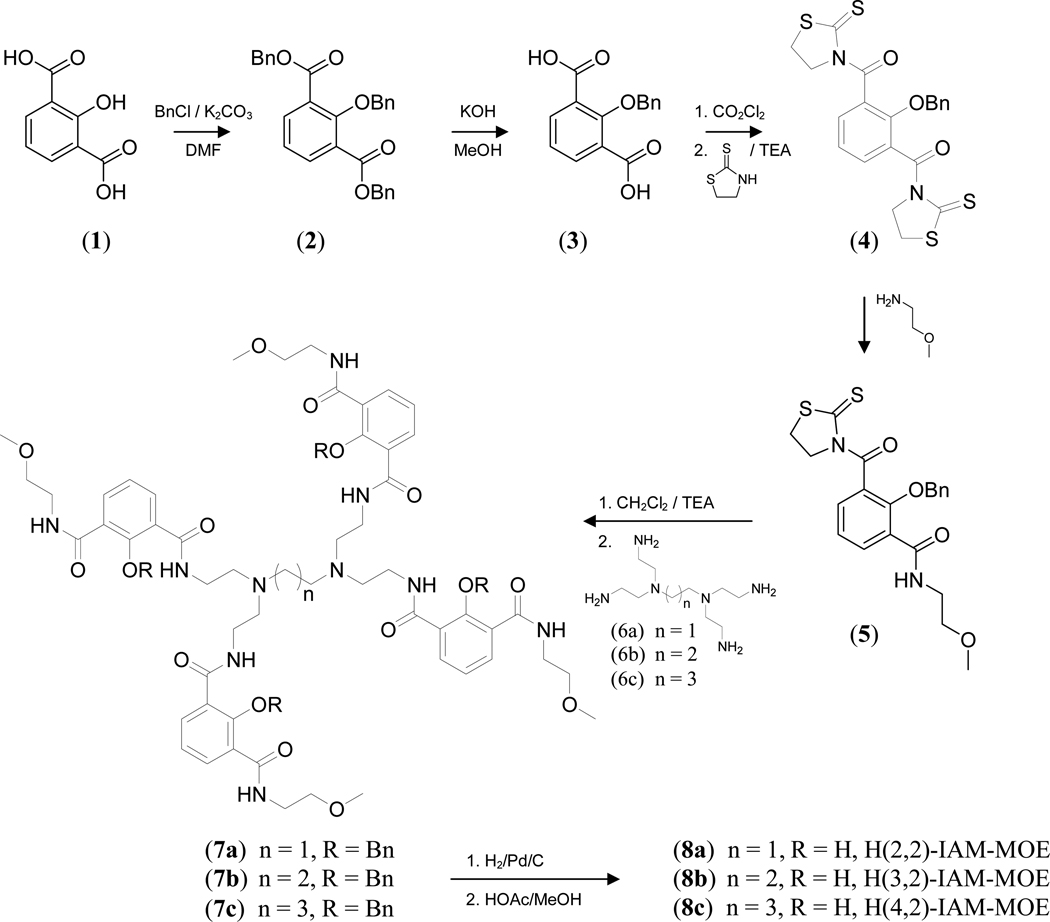

Scheme 1.

H(n,2)-IAM-MOE Ligand Synthesis (n = 2, 3, 4)

Synthesis

Dibenzyl 2-(benzyloxy)benzene-1,3-dicarboxylate (2)

2-Hydroxyisophthalic acid (75 g, 0.38 mol), benzyl chloride (158 g, 1.25 mol) and anhydrous K2CO3 (172 g, 1.25 mol) were added to 500 mL of dry DMF. The mixture was heated at 75°C under nitrogen for 18 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature and filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness under vacuum. The resulting residue was dissolved in 2 L of CH2Cl2 and filtered through a silica gel plug. A thick pale yellow oil was obtained after evaporation of the solvent. Yield: 158 g (90%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 5.07 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.31 (s, 4H, CH2), 7.23 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.3–7.4 (m, 15H, ArH), 7.97 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O-NaOD) δ: 66.9, 77.7, 123.5, 127.1, 127.7, 128.0, 128.0, 128.1, 128.2, 128.3, 134.8, 135.3, 136.6, 157.8, 165.2 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 453 [MH+].

2-(Benzyloxy)benzene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (3)

To a solution of 2 in 2 L of a 1:4 mixture of MeOH:H2O was added NaOH (40 g, 1.0 mol) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. The solvents were then removed under vacuum and the resulting residue was dissolved in brine and washed with CH2Cl2. The aqueous layer was acidified to pH 1 with conc. HCl, causing the product to precipitate out of solution. The product, a white solid, was collected by filtration and dried under vacuum. Yield: 85.6 g (92%): mp 235 – 237 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.23 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.39–7.41 (m, 3H, ArH), 7.425 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.48–7.51 (m, 2H, ArH), 8.35 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O-NaOD): δ 76.1, 123.4, 127.7, 128.0, 128.2, 128.5, 133.9, 136.2, 149.9, 176.6 ppm; MS (ESI-): m/z 271.1 [M−H]−.

(2-(Benzyloxy)-1,3-phenylene)bis((2-thioxothiazolidin-3-yl)methanone) (4)

To a solution of 3 (68 g, 0.25 mol) in dry dioxane, was added oxalyl chloride (76 g, 0.6 mol) and a drop of DMF while stirring. The mixture was heated at 60°C for 18 h under N2. The volatiles were then removed under vacuum and the resulting residue was first co-evaporated with dry dioxane and then dissolved in dry THF (300 mL). A solution of 2-mercaptothiozaline (72 g, 0.6 mol) and 70 mL of triethylamine in 200 mL dry THF was added drop-wise to the acyl chloride solution while being cooled in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was then warmed to room temperature and stirred for 10 h. The reaction mixture was then filtered and the yellow filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The resulting yellow residue was dissolved in 200 mL of CH2Cl2 and washed with 1 M HCl and 1 M KOH successively. Purification by column chromatography gave the product as a bright yellow solid. Yield: 75 g (63%): mp 149 – 151 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.03 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.41 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 5.02 (s, 3H, CH2), 7.02 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.3–7.4 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.49 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 28.8, 55.7, 77.1, 123.7, 127.7, 128.3, 128.5, 128.8, 132.2, 136.7, 153.3, 167.3, 200.8 ppm; MS (ESI+): m/z 497.0 [MNa+].

2-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2-methoxyethyl)-3-(2-thioxothiazolidine-3-carbonyl)benzamide (5)

To a solution of 4 (23.7 g, 0.05 mol) in CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was added a solution of 2-methoxyethylamine (0.75 g, 0.01 mol) in 50 mL isopropanol drop-wise over 8 h. Once the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was washed with 1 M KOH, then evaporated to dryness and applied to a silica gel column. The product, a yellow oily residue, was eluted with 1–5% MeOH in CH2Cl2. Yield 3.5 g (75%): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.95 (t, J = 5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.18 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.43 (t, J = 5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.57 (q, J = 5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.42 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H, CH2), 5.01 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.28 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.35–7.45 (m, 5H, ArH), 7.48 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.75 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.16 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 28.3, 39.5, 55.5, 58.5, 70.6, 77.5, 124.6, 127.3, 127.4, 128.4, 128.5, 129.7, 132.4, 134.0, 136.0, 154.0, 164.5, 167.1, 201.3 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 453.1 [MNa+].

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(Butane-1,4-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-(benzyloxy)-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (7c)

To a solution of 5 (1.94 g, 4.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (100 mL) was added N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-butane-1,4-diamine (6c)12 (0.26 g, 1 mmol) and the mixture was stirred for 9 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then evaporated to dryness and applied to a silica gel column. The product was eluted with 2–7% MeOH in CH2Cl2. Yield: 0.99 g (66%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.14 (s, 4H, CH2), 2.19 (s, 4H, CH2), 2.27 (t, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.18–3.22 (m, 20H, OCH3 + CH2), 3.44 (t, J = 5 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.55 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 4.96 (s, 8H, OCH2), 5.10 (s, 8H, NH), 7.13 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.30–7.36 (m, 20H, ArH), 7.53 (t, J = 6 Hz, 4H, NH), 7.72 (d, J = 6 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.74 (t, J = 6 Hz, 4H, NH), 7.96 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 24.3, 37.9, 39.7, 52.9, 53.8, 58.5, 70.7, 78.6, 124.8, 128.3, 128.5, 128.7, 128.8, 128.8, 133.5, 133.8, 135.5, 154.3, 165.2, 165.6 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1505.8 [MH+].

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(Ethane-1,4-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-(benzyloxy)-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (7a)

This compound was prepared using a procedure analogous to that described for 7c above, substituting N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-ethane-1,2-diamine (6a)12 where appropriate, to yield the desired product as a white foam (81%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.27 (q, J = 5 Hz, 12H, CH2), 3.16 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.21 (s, 12H, OCH3), 3.43 (t, J = 5 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.53 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 4.93 (s, 8H, OCH2), 7.12 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.29–7.34 (m, 20H, ArH), 7.56 (t, J = 6 Hz, 4H, NH), 7.63 (dd, J = 8, 2 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.82 (t, 4H, J = 6 Hz, NH), 7.92 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2 Hz, 4H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 37.3, 39.4, 51.6, 52.7, 58.2, 70.3, 78.3, 124.4, 128.1, 128.3, 128.4, 128.5, 128.7, 132.8, 133.2, 135.2, 153.9, 165.1, 165.4 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1477.5 [MH+].

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(Propane-1,4-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-(benzyloxy)-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (7b)

This compound was prepared using a procedure analogous to that described for 7c above, substituting N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(2-aminoethyl)-propane-1,3-diamine (6b)12 where appropriate, to yield the desired product as a white foam (83%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.24 (q, 2H, J = 7 Hz, CH2), 2.17 (t, 4H, J = 7 Hz, CH2), 2.23 (t, 8H, J = 6 Hz, CH2), 3.13 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.16 (s, 12H, OCH3), 3.38 (t, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.49 (q, 8H, J = 6 Hz, CH2), 4.86 (s, 8H, OCH2), 7.08 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.30–7.40 (m, 20H, ArH), 7.53 (t, J = 6 Hz, 4H, NH), 7.63 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 2 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.75 (t, 4H, J = 6 Hz, NH), 7.90 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2 Hz, 4H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 37.4, 39.4, 51.4, 52.5, 53.3, 58.2, 70.3, 78.2, 124.4, 128.0, 128.2, 128.4, 128.5, 128.7, 133.0, 133.2, 135.2, 154.0, 165.0, 165.4 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1492.7 [MH+].

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(Butane-1,4-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-hydroxy-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (8c) (H(4,2)-IAM-MOE)

To a solution of 7c (0.9 g, 0.6 mmol) in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of glacial acetic acid and methanol (75 mL) was added 0.15 g of 10% Pd/C. The mixture was hydrogenated at atmospheric pressure for 18 h. The catalyst was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness to give the product as a beige solid. Yield: 0.58 g (85%): 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.85 (s, 4H, CH2), 3.25 (s, 12H, OCH3), 3.31 (s, 4H, CH2), 3.38 (s, 8H, CH2), 3.46 (s, 16H, CH2), 3.75 (q, J = 5 Hz, 8H, CH2), 6.95 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 8.09 (d, J = 8 Hz, 8H, ArH), 8.94 (s, 4H, NH), 9.22 (s, 4H, NH), 10.83 (s, 4H, OH) ppm; 1H NMR (125 MHz, D2O-NaOD): δ 1.19 (s, 4H, CH2) 2.26 (s, 4H, CH2) 2.48 (t, 8H, J = 6 Hz, CH2), 3.12 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.23 (q, J = 7 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.27 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 3.33 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 6.40 (t, J = 8 Hz, ArH), 7.74 (t, J = 8 Hz, 8H, ArH) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSOd6): δ 15.5, 20.5, 34.5, 39.2, 51.7, 52.3, 58.3, 65.3, 70.5, 118.0, 118.5, 118.5, 133.4, 133.7, 160.1, 167.7, 168.0 ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1145.5 [MH+], 1169.5 [MNa+]. Anal. Calcd. (Found) for C56H76N10O16·2HCl·1.5H2O: C, 54.02 (53.92); H, 6.55 (6.71); N, 11.25 (11.04).

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(ethane-1,3-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-hydroxy-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (8a) (H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)

This compound was prepared using a procedure analogous to that described for 8c, yielding the desired product (77%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O-NaOD): δ 2.62 (t, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 2.66 (s, 4H, CH2), 3.08 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.27 (q, J = 6 Hz, 16H, CH2), 3.53 (q, 8H, J = 6 Hz, CH2), 6.38 (t, 4H, J = 8 Hz, ArH), 7.72 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH) ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1117.5 [MH+], 1139.5 [MNa+]; Anal. Calcd. (Found) for C54H72N10O16·2HCl·1.5H2O: C, 53.28 (53.30); H, 6.38 (6.51); N, 11.51 (11.23).

N1,N1',N1",N1'"-(2,2',2",2'"-(propane-1,3-diylbis(azanetriyl))tetrakis(ethane-2,1-diyl))tetrakis(2-hydroxy-N3-methylbenzene-1,3-dicarbamide) (8b) (H(3,2)-IAM-MOE)

This compound was prepared using a procedure analogous to that described for 8c, yielding the desired product (73%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O-NaOD): δ1.22 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.26 (s, 4H, CH2), 2.36 (s, 4H, CH2), 3.06 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.17 (q, J = 7 Hz, 16H, CH2), 3.43 (q, J = 6 Hz, 8H, CH2), 6.39 (t, 4H, J = 8 Hz, ArH), 7.62 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H, ArH) ppm; MS (FAB+): m/z 1131.6 [MH+]; Anal. Calcd. (Found) for C55H74N10O16·2HCl·1H2O: C, 54.05 (54.20); H, 6.43 (6.79); N, 11.46 (11.10).

Solution Thermodynamics

Experimental protocols and details of apparatus closely followed those of previous studies.13,14 The resulting potentiometric data (pH vs total proton concentration) were refined using Hyperquad. For spectrophotometric titrations, a titration vessel was charged with 100 mL (± 0.05 mL) of degassed 0.1 M KCl, and external non-coordinating buffers including MES, HEPES and NH4Cl were added as solid acids in order to achieve final concentrations of ca. 0.25 mM to ensure proper pH buffering. After acquisition of a reference (blank) spectrum, addition of the ligand as a solid was executed to give a final concentration of approximately 20 µM. Subsequently, one equivalent of standardized Eu(III) or Tb(III) solution (0.0451 M and 0.0510 M respectively) was added via Eppendorf micropipette, and an aliquot of standardized 0.1 M HCl (200 µL) was added to adjust the pH to approximately 3.5. Solutions were titrated with 0.1 M KOH (using aliquots of 15–35 µl) to an endpoint of pH 10.0, and subsequently back-titrated with standardized 0.1 M HCl (using aliquots of 15–35 µl) to pH 3.5, with equilibration times of 300 s between each addition. Absorbance spectra (280–380 nm, 2 nm data interval) were collected and pH recorded for each addition. The data from each titration (absorbance vs. pH) were imported using pHab for data analysis and were separately treated by non-linear least squares refinement. All equilibrium constants are defined in terms of βmlh, using the equation:

Hydrolysis constants for Eu(III) (β101 = −7.1, β102 = −15.6, β103 = −24.6) and Tb(III) (β101 = −7.2, β102 = −15.3, β103 = −24.0) were estimated using the methods described in Baes and Mesmer for an ionic strength of I = 0.1 M.15 These were included as fixed values in the refinement, together with the values for ligand proton association constants obtained from potentiometry (β011… β016), and absorbances were refined only for species present above 5% under the experimental conditions (the species ML, MLH, MLH2, MLH3, LH5 and LH6 were defined as absorbing).16 Factor analysis showed at least some regular structure for the first six eigenvectors, consistent with this number of species. A common model was used for all three ligands, with both Eu(III) and Tb(III). Wavelengths from 280–320 nm and 330–360 nm, excluding the isosbestic point, were used in the refinement, yielding global σ values between 2 and 5.5. Notably, for H(2,2)-IAM-MOE and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, titrations were reversible for the whole pH range of 3.5–10 while for H(3,2)-IAM-MOE, only the pH range from 3.5–7 was used in the refinement due to irreversibility above pH 7 consistent with hydrolysis.

Photophysics

Absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 300 double beam UV-Visible spectrophotometer using a quartz cell of 1 cm path length. Emission spectra were recorded on a HORIBA Jobin Yvon IBH FluoroLog-3 spectrofluorimeter using 1 cm quartz SUPRASIL luminescence cells for room-temperature measurements. Spectra were reference corrected for both the excitation light source variation (lamp and grating) and the emission spectral response (detector and grating). Both the Tb(III) and Eu(III) samples for photophysical measurements were prepared in situ at stock concentrations of 10 µM in 0.1M TRIS buffered H2O (pH 7.4) and then diluted where required. Quantum yields were determined by the optically dilute method17 using the equation: where A is the absorbance at the excitation wavelength (), I is the intensity of the excitation light at the same wavelength, n is the refractive index and D is the integrated intensity. Quinine sulfate in 1.0 N sulfuric acid was used as the reference (Qr = 0.546).18 Luminescence lifetimes were determined with a HORIBA Jobin Yvon IBH FluoroLog-3 spectrofluorimeter, adapted for time resolved measurements. A submicrosecond Xenon flash lamp (Jobin Yvon, 5000XeF) was used as the light source, coupled to a double grating excitation monochromator for spectral selection. The input pulse energy (100 nF discharge capacitance) was ca. 50 mJ, giving an optical pulse duration of less than 300 ns at FWHM. A thermoelectrically cooled single photon detection module (HORIBA Jobin Yvon IBH, TBX-04-D) incorporating fast rise time PMT, wide bandwidth pre-amplifier and picosecond constant fraction discriminator was used as the detector. Signals were acquired using an IBH DataStation Hub photon counting module and data analysis was performed using the commercially available DAS 6 decay analysis software package from HORIBA Jobin Yvon IBH. Goodness of fit was assessed by minimizing the reduced chi squared function, χ2, and a visual inspection of the weighted residuals. Each trace contained at least 10,000 points and the reported lifetime values result from at least three independent measurements. Low temperature emission spectra for the Gd(III) complexes were recorded at 77 K on a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter, using solutions of the complex prepared in situ in an appropriate glass forming solvent (1:4 (v/v) MeOH:EtOH).19

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

A general synthetic route for the H(n,2)-IAM-MOE (n = 2, 3, 4) ligands is shown in Scheme 1. The initial step is benzyl protection of 2-hydroxyisopthalic acid (1). The use of the benzyl protecting group rather than a methyl group is necessary as this group can be easily removed using mild deprotection conditions that will leave the subsequently installed MOE ether moieties intact. The resulting dibenzyl ester (2) is hydrolyzed to give 2-benzyloxyisophthalic acid (3), which is first converted to the diacyl chloride and then coupled directly with two equivalents of 2-mercaptothiazoline to give the key dithiazolide intermediate (4). Using the dithiazolide allows for facile asymmetric substitution of the molecule using differing amines. Slow addition of 2-methoxyethylamine to an excess of the dithiazolide (4) yields the monosubstituted species (5). The monothiaz (5) can be easily purified using column chromatography from unreacted starting material, which can be isolated for later re-use. The monoamide (5) is then coupled to each of the amine backbones (6a–c), synthesized according to literature procedures,12 to yield the protected ligands (7a–c). Removal of the remaining benzyl protecting groups was achieved under standard hydrogenation conditions to furnish the final desired ligands (8a–c).

Solution Thermodynamics

The protonation constants for each ligand were determined by potentiometry, with the results as summarized in Table 1. It can be seen that the values for each ligand differ only slightly, and there are no clear trends in the protonation constants as a function of the amine backbone. From the sum of logKa values, it is apparent that H(3,2)-IAM-MOE is the least basic ligand, with logβ016 = 40.55, followed by H(4,2)-IAM-MOE with logβ016 = 41.32, while H(2,2)-IAM-MOE is the most basic with logβ106 = 42.75. For each of the ligands the first two protonation constants are well separated, while the last four are clustered together, which is consistent with a preliminary assignment of the first two protonations to the tertiary amines present in the alkylamine backbone, and the remaining four corresponding to protonation of the IAM phenolates.

Table 1.

Summary of ligand protonation constants† for H(n,2)-IAM-MOE ligands.

| Ligand | logβ011 | logβ012 | logβ013 | logβ014 | logβ015 | logβ016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H(2,2)-IAM-MOE | 9.47(1) | 17.52(2) | 24.81(2) | 31.29(2) | 37.41(2) | 42.75(2) |

| H(3,2)-IAM-MOE | 9.16(3) | 17.12(5) | 23.99(5) | 30.30(5) | 36.00(5) | 40.55(6) |

| H(4,2)-IAM-MOE | 9.38(1) | 17.55(2) | 24.47(2) | 30.74(2) | 36.44(3) | 41.32(3) |

| assignment‡ | backbone | backbone | IAM | IAM | IAM | IAM |

Based on three potentiometric experiments (including forward and reverse): σ = 1.47 for H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, σ = 1.12 for H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, σ = 1.94 H(3,2)-IAM-MOE.

Based on spectrophotometric experiments (including forward and reverse).

To confirm this assignment, spectrophotometric titrations of each ligand were also performed. In every case, the first protonation causes the least change in the molar absorptions in the region of the IAM π−π* transition, and is therefore consistent with protonation of the amine backbone. It is worth noting that the observed logKa values (ca. 9) are in the range expected for non-interacting tertiary amines, whereas hydrogen bonding with the amide NH protons of the IAM arms would be expected to lower the logKa’s significantly, as observed previously for tren-based ligands.20,21 For H(4,2)-IAM-MOE and H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, the second protonation also involves a small change in molar absorption and is likely dominated by tertiary nitrogen protonation. The last four protonations, which result in the largest changes in the molar absorptions, are dominated by IAM protonations. For H(3,2)-IAM-MOE, the smallest change in molar absorption corresponds to the loss of the most acidic proton indicating that for this ligand, the last protonation involves the amine backbone to some degree. The mean values for the logKa’s assigned to IAM protonation (ca. 6) are in the expected range for the IAM chromophore.

While the pendant monoethylene glycol groups significantly improved the ligand solubilities, the improvement was not sufficient to allow for direct potentiometric examination of the Ln(III) complexes. The stability constants for Tb(III) and Eu(III) with the H(n,2)-IAM-MOE ligands were determined by spectrophotometric titrations, and the results are summarized in Table 2. A representative titration (for Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE) in shown in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information. From the spectrophotometric data for each of the six complexes examined, four distinct Ln(III) species were observed in each case: a minor species involving a protonated IAM ligand (i.e. MLH3) and three complexes that differ in the protonation state of the two tertiary amine nitrogens in the backbone (i.e. ML, MLH, and MLH2). An examination of the calculated molar absorbance values revealed that the latter two protonation steps involve only a small change in the molar absorbance, while the UV absorption spectrum calculated for the MLH3 species is significantly different, consistent with protonation of one of the IAM arms.

Table 2.

Summary of stability constants for H(n,2)-IAM-MOE ligands with Tb(III) and Eu(III).

| Complex | logβ110 | logβ111 | logβ112 | logβ113 | pM† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE) | 14.7(1) | 24.1(1) | 30.3(1) | 34.2(1) | 14.7 |

| Tb(H(3,2)-IAM-MOE) | hydrolysis | 19.9(1) | 26.1(1) | 31.3(1) | 10.9 |

| Tb(H(4,2)-IAM-MOE) | 13.2(2) | 21.4(2) | 27.2(1) | 31.8(1) | 12.1 |

| Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE) | 14.4(1) | 23.6(1) | 29.9(1) | 32.8(1) | 14.3 |

| Eu(H(3,2)-IAM-MOE) | hydrolysis | 20.5(1) | 26.3(1) | 31.3(1) | 11.1 |

| Eu(H(4,2)-IAM-MOE) | 13.6(3) | 21.7(2) | 27.3(2) | 31.5(1) | 12.4 |

pM Calculated under conditions of [M]total = 10−6 M, [L]total =10−5 M, pH = 7.4 (25°C, 0.1 M KCl)

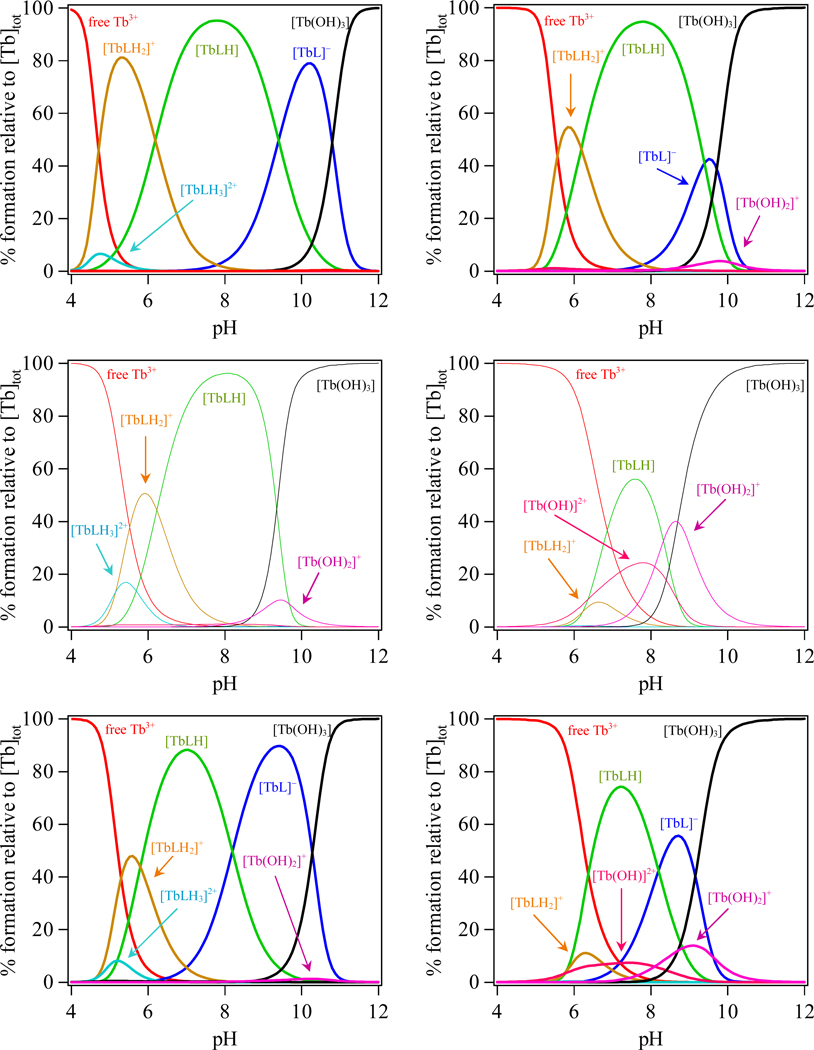

The resulting metal complex formation constants reveal distinct trends in stability, with the observed Ln(III) affinities reflecting the changes in ligand basicity, leading to significant differences in the complex speciation and stability at low pH and upon dilution. The most basic ligand, H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, forms the most stable complexes with both Tb(III) and Eu(III) while the least basic ligand, H(3,2)-IAM-MOE, forms the least stable complexes. The resulting speciation diagrams for the three Tb(III) complexes calculated at micromolar (1 µM) and nanomolar (1 nM) concentrations are compared in Figure 2, and corresponding plots for the Eu(III) complexes are given in Figure S2 in the Supporting Information. These plots show that at physiological pH, the predominant species in solution is the neutral MLH species. From a closer inspection of these figures, it is also evident that the Ln(III) complexes of both the H(2,2)- and to a lesser extent H(4,2)-IAM-MOE ligands retain their stability under acidic conditions, with the percent formation of free Ln(III) accounting for less than 5% of the speciation under nM concentration conditions (0.3% and 4.7% for Tb(III) for H(2,2)- and H(4,2)-ligands, respectively). By contrast, the more weakly binding H(3,2)-IAM-MOE ligand is more susceptible to decomplexation, yielding ca. 14.2% of free Tb(III) under the same conditions. Moreover, for both the H(4,2)- and H(3,2)- ligands, hydrolysis of the metal to form [Ln(OH)]2+ becomes competitive at nanomolar concentration, accounting for approx 22.6% and 7.4% of the speciation respectively, while for the H(3,2)- ligand, hydrolysis is evident even at micromolar concentrations.

Figure 2.

Speciation diagrams for Tb(H(n,2)-IAM-MOE) series (n = 2, 3 and 4 from top to bottom) calculated at 10−6 M (left column) and 10−9 M (right column) in aqueous solution.

The spectrophotometric titrations for H(3,2)-IAM-MOE with both Eu(III) and Tb(III) were irreversible above pH 7, consistent with competing alkaline hydrolysis of the complex. As such, the logβ110 formation constants for the ML complexes could not be determined accurately and are instead denoted by “hydrolysis” in Table 2, although these values can be estimated to be about 8.5 – 9 by a consideration of the calculated speciation under the conditions of the spectrophotometric titration. As a result of this much weaker formation constant, the onset of metal hydrolysis is also more rapid for the Ln(III) complexes with H(3,2)-IAM-MOE under alkaline conditions at nM concentrations, with the speciation of [Ln(OH)2]+ and [Ln(OH)3] summing to a total of 95% by pH 9 (compared to greater than ca. pH 10.3 and 9.8 necessary for the complexes with H(2,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE respectively to attain similar speciation). Indeed, for the H(3,2)- ligand, this hydrolysis is also readily evident at micromolar concentration.

Therefore, it is apparent that the Ln(III) complexes formed with the ligand H(2,2)-IAM-MOE will be stable at nM concentration whereas complexes formed with H(3,2)-IAM-MOE and to a lesser extent H(4,2)-IAM-MOE are not. A comparison of the sum of the total speciation at pH 7.4 for the [TbLHx] (x = 0,1,2,3) complexes versus concentration as shown in Figure S9 (Supp. Info.) reveals that complexes with the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand are stable (i.e. amount to more than 95% of the speciation) upon further dilution to a limiting concentration of ca. 10−11 M, whereas the H32- and H42- ligands begin to show similar levels of dissociation at ca. 10−7 M and 10−8 M respectively.

For all six [Ln(H(n,2)-IAM-MOE)] complexes, the affinity constants increase as the ligand is successively deprotonated and the negative charge of the ligand is increased. For both the Tb(III) and Eu(III) complexes of H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, however, the affinity constant for MLH is only slightly smaller (ca. 1 kJ.mol−1) than that of the ML complex (Table S1, Supp. Info.), whereas for the remaining complexes, the affinity constants are separated by ca. 5–10 kJ.mol−1. We attribute this to a strong hydrogen bond interaction between the protonated tertiary amine and the neighboring free amine in the backbone of the MLH species. The LH free ligand species can be thought of as being predisposed for metal binding by this intramolecular hydrogen bond between the two tertiary amine nitrogens of the central portion of the backbone. This effect also likely contributes strongly to the stability of the Ln(III) complexes with H(2,2)-IAM-MOE. Also, while the Eu(III) and Tb(III) complexes have comparable affinities, these ligands do show some selectivity according to their sizes; H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, which should have the smallest binding cavity, selects the smaller Tb(III) (1.18 Å) over Eu(III) (1.206 Å) cation.22 Consistent with this observation, H(3,2)-IAM-MOE and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE which should have larger binding cavities, have higher pM values for Eu(III) than for Tb(III).

Based on these solution thermodynamic data, which predict the onset of complex dissociation at 10−11 M for [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)], we have reinvestigated our previous report of a minimum detectable concentration of 10−15 M for the parent [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM)] complex.6 A double logarithmic plot of the luminescence intensity versus concentration for this complex at pH 7.4 in 0.01 M phosphate buffer is shown in Figure S10 (Supp. Info), from which it is readily apparent that the luminescence intensity drops almost linearly with log concentration until ca. 10−10 M and is barely visible at 10−11 M (see Figure S11, Supp. Info.). While not apparent from the steady state measurement upon further 10 fold dilution of this sample, we were able to discern the characteristic 2.60 msec lifetime of the Tb(III) complex by time resolved measurements, and hence we can estimate a limiting concentration of 10−12 M. Significantly, this limiting value also corresponds to the approximate detection limit of our fluorimeter.23 We conclude that our earlier result was likely due to the formation of partially hydrolyzed 6species (e.g. [TbL(OH)x]) that are known to adhere to glass surfaces, and can easily contaminate measurements performed at such high dilution. Despite this decrease in the estimated minimum detectable concentration, these complexes are stable enough for use in bioassays, which are typically performed at nano- or picomolar concentrations.

Photophysics

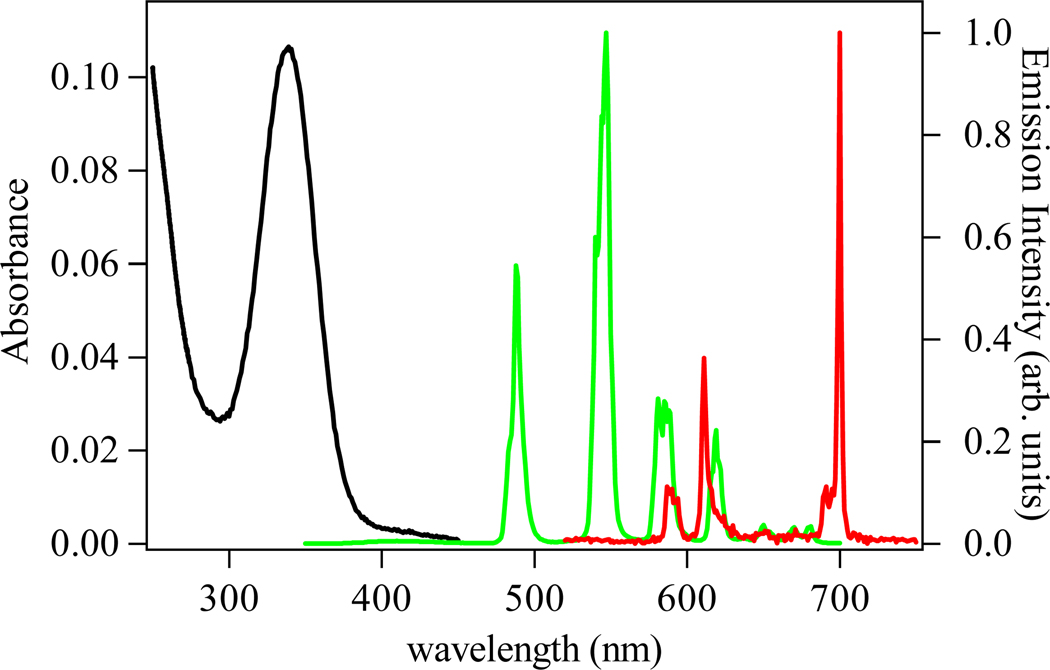

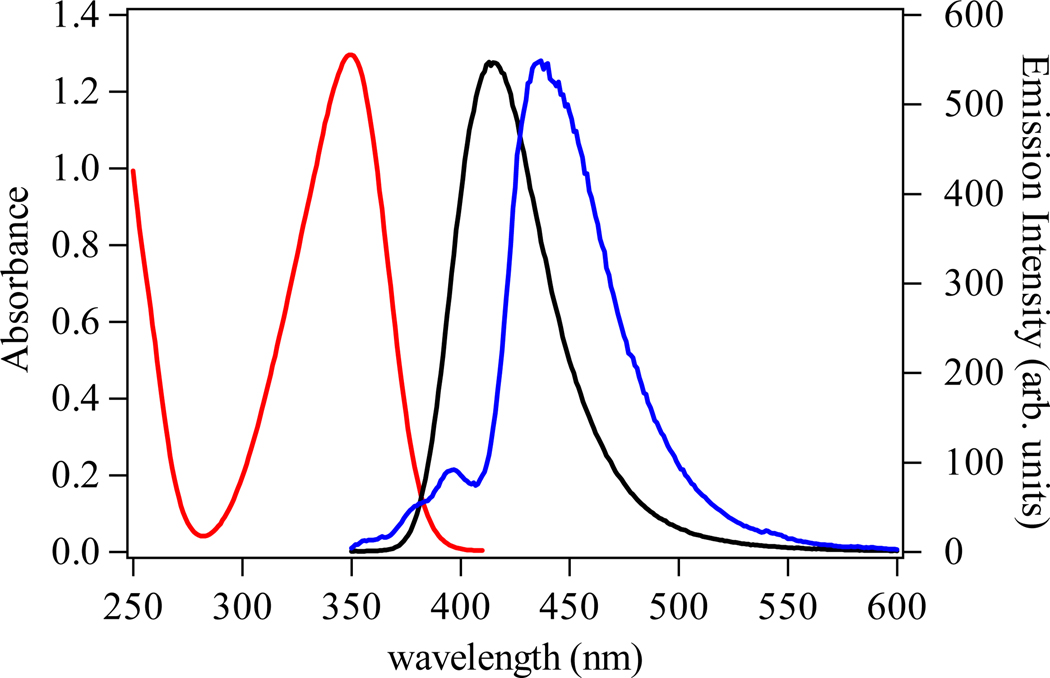

The absorption and emission spectra of the H(n,2)-IAM-MOE ligands series are essentially identical. The spectra of the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand are shown in Figure 4 as a representative example. Each of the three ligands displays a broad electronic envelope with a maximum centered at ca. 350 nm, which we assign to π −π* transitions of the IAM chromophore. The corresponding room temperature emission spectra of the ligands are similarly broad, with maxima centered at ca. 416 nm, corresponding to emission from the excited singlet state. The similarity in absorption and emission characteristics of the three ligands indicates that modification of the amide by altering the ligand backbone does not significantly alter the photophysical properties of the IAM chromophore.

Figure 4.

The absorbance (black) and emission spectra (green) (λexc = 340 nm) of a 5 µM solution of [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex in 0.1 M TRIS buffer at pH 7.4. The corresponding emission spectrum of the [Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex is shown in red.

Also shown in Figure 3 is the emission spectrum of the [Gd(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex, measured at 77K in a MeOH/EtOH (1:5 (v/v)) glass, in which emission arising from the ligand centered 3π−π* state is evident. The corresponding spectra for the H(3,2)- and H(4,2)- complexes are shown in Figures S3 and S4 in the Supporting Information. From spectral deconvolution, estimates of the energies of the 0-phonon transition of the triplet states (T0-0) for each Gd(III) complex were obtained, yielding values of 23,170 cm−1, 23,260 cm−1 and 23,030 cm−1 for the complexes with H(2,2)-, H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, respectively. The S1 and T0-0 excited states for all three of the complexes are close in energy (ΔEavg (S1 – T0-0) = 850 cm−1), which suggests the efficiency of intersystem crossing could be very high. Moreover, the mean T0-0 energy is ca. 2,750 cm−1 higher in energy than the Tb(III) 5D4 emitting state, which is in the range proposed for optimal ligand-to-Tb(III) energy transfer.24 The emission spectrum of the Gd(III) complex of the previously reported H(2,2)-IAM ligand was also measured and from this spectrum (Figure S12) the T0-0 energy was estimated to be ca. 23,350 cm−1, which is close to the values for the H(n,2)-IAM-MOE ligands. This shows that the addition of the monoethylene glycol groups does not alter the photophysics of the IAM ligand.

Figure 3.

The observed room temperature absorption (red) and emission spectra (black) of the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand in 0.1 M TRIS buffer at pH 7.4, and corresponding 77 K emission spectra for the Gd(III) complex (blue) in 1:5 (v/v) MeOH:EtOH.

The luminescence spectra of the [Tb(H(n,2)-IAM-MOE)] complexes all show the characteristic emission arising from the transitions from the 5D4 electronic level to the 7FJ manifold centered on Tb(III). The spectrum of the [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex is shown in Figure 4, with corresponding spectra for the H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE complexes shown in Figures S5 and S6 in the Supporting Information. All of the complexes show only weak residual ligand emission, indicating efficient ligand-to-lanthanide energy transfer. To quantify this efficiency, the quantum yields of the overall energy transfer processes were measured, and the results are summarized in Table 3. The quantum yield values are very high, at 0.57, 0.41 and 0.52, for the Tb(III) complexes of H(2,2)-, H(3,2)-, and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, respectively. The quantum yield value for H(2,2)-IAM-MOE is similar (within experimental error) to the previously reported quantum yield for the parent [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM)] complex,6 demonstrating that the addition of the monoethylene glycol solubilizing groups has little effect on the photophysical properties of the Ln(III) complexes. It seems that, the Tb-IAM family of complexes are among the most luminescent Tb(III) complexes reported in aqueous solution (without the addition of agents such as fluoride or micelles).

Table 3.

Summary of photophysical data for H(n,2)-IAM-MOE complexes with Tb(III) and Eu(III) in 0.1 M TRIS buffer at pH = 7.4 (λexc = 338 nm).

| Complex | Φtot (%) | τH2O (ms) | τD2O (ms) | q† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 56 | 2.63 | 3.27 | 0.1 |

| [Tb(H(3,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 39 | 1.39 | 1.91 | 0.7 |

| [Tb(H(4,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 52 | 1.37 | 1.83 | 0.6 |

| [Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 0.14 | 0.650 | 0.887 | 0.2 |

| [Eu(H(3,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 0.15 | 0.548 | 0.694 | 0.2 |

| [Eu(H(4,2)-IAM-MOE)] | 0.58 | 0.580 | 0.750 | 0.2 |

Calculated using the equations from Ref. 25; q = 5 × (1/τH2O − 1/τD2O − 0.06) for Tb(III), q = 1.2 × (1/τH2O − 1/τD2O − 0.25) for Eu(III).

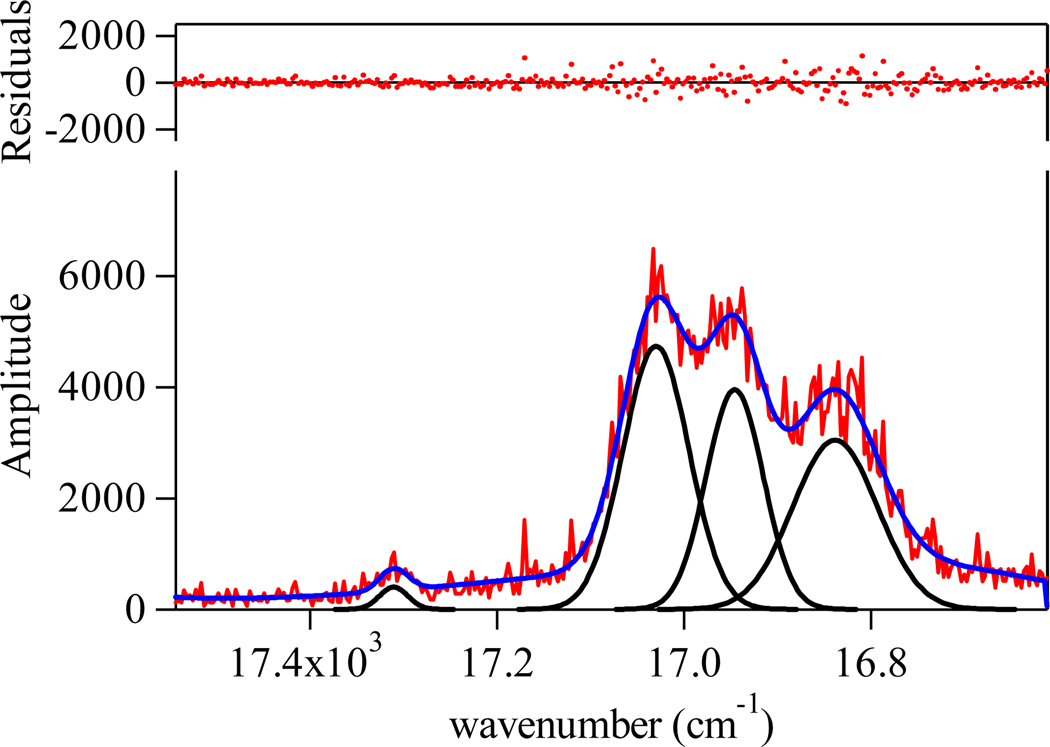

The luminescence spectrum of the [Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex is also shown in Figure 4 and shows the characteristic Eu(III) centered emission, again with corresponding spectra for the H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE complexes given in the Figures S5 and S6 (Supp. Info.). A closer analysis of the J = 0, 1 bands is shown in Figure 5. Unfortunately, the limited resolution of our instrument (ca. 0.3 nm) and the effect of inhomogeneous line broadening in solution did not allow for a definitive assignment of the exact symmetry point group for the first coordination sphere, since the J = 2 region is poorly resolved. However, for the 5D0 → 7F1 transition, crystal field splitting of the J = 1 level results in a maximum of three (2J + 1) peaks in a low symmetry environment (e.g. C2v) versus only two peaks for the hexagonal, trigonal or tetragonal point groups (e.g. D2d, D4d).1 The presence of three peaks in the J = 1 region for each of the three complexes is readily apparent, and hence, the possible choices are restricted to either the orthorhombic (D2, C2v), monoclinic (C2, Cs), or triclinic point groups (C1). It is also of interest to note that emission from the hypersensitive J = 2 band at ca. 612 nm for the [Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex is very weak, when compared to the corresponding intensity of the other two complexes. The exact reason for this is not clear and is complicated by the known hypersensitivity of this transition. Slight elongation of the central backbone is sufficient to relax this effect, as evidenced by an increase in the intensity of the 612 nm peak and an increase in overall quantum yield (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Expansion of the emission spectrum for the [Eu(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex in 0.1 M TRIS buffer (pH 7.4) in the J = 0, 1 region and corresponding fit of the experimental spectrum to four overlapping Gaussians functions.

In addition to their steady state emission, the luminescent lifetimes of the Tb(III) and Eu(III) complexes were measured, with results summarized in Table 3. The lifetimes were measured in both H2O and D2O to allow the number of bound water molecules to be estimated, using the equations of Beeby and Parker et al:25 q = 5.0 × (kH2O − kD2O − 0.06) for Tb(III) and q = 1.2 × (kH2O − kD2O − 0.25) for Eu(III) where kH2O and kD2O are the reciprocal luminescence lifetimes in H2O and D2O respectively. The [Tb(H(2,2)-IAM-MOE)] complex displays long lifetimes of 2.63 and 3.27 ms in H2O and D2O, respectively, and has a q value of essentially zero. This result confirms that the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand provides excellent protection from bound solvent water molecules, and is consistent with the high quantum yield observed for this complex. The lifetimes of the Tb(III) complexes of H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE in aqueous solution are markedly shorter (1.39 and 1.37 ms respectively), suggesting significant non-radiative deactivation of metal centered luminescence. The q values determined for these complexes indicate that both have a single residual water molecule in the inner coordination sphere. This explains the lower quantum yields observed for these two complexes relative to that of the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE Tb(III) complex. Evidently, the binding cavities created by H(3,2)-IAM-MOE and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE are large enough to accommodate a water molecule bound to the Tb(III) ion. The [Eu(H(n,2)-IAM-MOE)] complexes display lifetimes of 0.65 (n = 2), 0.55 (n = 3) and 0.58 ms (n = 4) in H2O. In contrast to the Tb(III) complexes, the q values calculated for all three Eu(III) complexes are essentially zero. This was surprising to us since Eu(III), the larger ion, can accommodate a higher coordination number than Tb(III).

Conclusions

A series of three octadentate ligands featuring the 2-hydroxyisophthalamide (IAM) antenna chromophore with improved water-solubility has been synthesized and the effect of altering the ligand backbone on the resulting solution stability and photophysical behavior was investigated. Solution thermodynamic studies of the Tb(III) and Eu(III) complexes show that the complexes of H(2,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE are stable at nanomolar concentration (sufficient for practical applications in fluoroimmunoassays) whereas the Ln(III) complexes with H(3,2)-IAM-MOE are not, showing evidence of hydrolysis at nM concentrations. An examination of the Ln(III) affinities and the speciation of the L4− and LH3− ligand forms, especially for H(2,2)-IAM-MOE, suggests that the protonated ligand (LH3−) is predisposed for metal binding due to a critical intramolecular hydrogen bond between the tertiary amines of the ligand backbone. The photophysical performance of the Ln(III) complexes displays impressive quantum yields for Tb(III), with an optimum result of Φtot = 56% with the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand. For the remaining Tb(III) complexes, the presence of a water molecule in the inner coordination sphere diminishes the luminescence performance, and the overall quantum yields of the H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE complexes are lowered relative to the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE. As a result of their superior photophysical performance and stability, structurally similar IAM ligand derivatives that utilize the H(2,2)- backbone discussed herein have been recently commercialized and utilized as a luminescent probe for high sensitivity Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF®) technology.26

Synopsis.

A series of three water-solubilized antenna ligands that sensitize Tb(III) and Eu(III) luminescence has been synthesized. The ligand backbones were varies to investigate its effect on the stability and photophysical properties of the their Ln(III) complexes. Ligand protonation constants and Tb(III) and Eu(III) formation constants were determined from solution thermodynamic studies. The resulting values indicate that at physiological pH, the Eu(III) and Tb(III) complexes of H(2,2)-IAM-MOE is sufficiently stable to prevent dissociation at nanomolar concentrations. The combined brightness and stability of these complexes make them well suited to serve as the luminescent reporter group in high sensitivity time-resolved fluoroimmunoassays.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the NIH (Grant HL69832) and supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, and the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences of the U.S. Department of Energy at LBNL under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The University of California patents for this technology are exclusively licensed to Lumiphore, Inc., in which some of the authors have a financial interest. We thank Dr. Stephane Petoud for his prior contributions to these studies.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Calculated free energy changes derived from affinity constants of Tb(III) and Eu(III) with the H(2,2)-IAM-MOE ligand. Speciation diagrams for Eu(H(n,2)-IAM-MOE) calculated at 10−6 M and 10−9 M. Room temperature absorption and emission spectra of the H(3,2)- and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE, and 77 K emission spectra for the Gd(III) complexes. Representative spectrophotometric titration data for Tb(H(2,2)-MOE-IAM. Absorbance and emission spectra of Tb(III) and Eu(III) complexes of H(3,2)-and H(4,2)-IAM-MOE. Room temperature and 77 K emission of parent [Gd(H(2,2)-IAM)] complex. High resolution emission spectra for [Eu(H(3,2)-IAM-MOE)] and [Eu(H(4,2)-IAM-MOE)] in the J = 0, 1 region and corresponding fits of the experimental spectrum to Gaussian functions. Emission spectra and stability data for [Tb(H22-IAM)] at high dilution based on solution thermodynamic data. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bünzli J-CG. In: Lanthanide Probes in Life, Chemical and Earth Sciences: Theory and Practice. Bünzli J-CG, Choppin GR, editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemmila I, Laitala V. J. Fluor. 2005;15:529–542. doi: 10.1007/s10895-005-2826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charbonniere LJ, Hildebrandt N, Ziessel RF, Loehmannsroeben H-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;39:12800–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja062693a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemmila IJ. Alloys Compd. 1995;225:480–485. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bünzli J-C, Piguet C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:1048–1077. doi: 10.1039/b406082m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petoud S, Cohen SM, Bünzli J-C, Raymond K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13324–13325. doi: 10.1021/ja0379363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petoud S, Muller G, Moore EG, Xu J, Sokolnicki J, Riehl JP, Le UN, Cohen SM, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:77–83. doi: 10.1021/ja064902x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seitz M, Moore EG, Ingram AJ, Muller G, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15468–15470. doi: 10.1021/ja076005e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raymond KN, Petoud S, Cohen SM, Xu J. USA: 2002. Vol. US 6406297 B1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raymond KN, Petoud S, Cohen SM, Xu J. USA: 2003. Vol. 6515113 B2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurchen KMC, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:1078–1090. doi: 10.1021/ic0512882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernhardt PV. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:1086–1092. doi: 10.1021/ic000928s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SM, O'Sullivan B, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:4339–4346. doi: 10.1021/ic000239g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, O'Sullivan B, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:6731–6742. doi: 10.1021/ic025610+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baes CF, Mesmer RE. The Hydrolysis of Cations. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical Stability Constants. Vol. 4. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosby GA, Demas JN. J. Phys. Chem. 1971;75:991–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meech SR, Philips D. J. Photochem. 1983;23:193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott DR, Allison JB. J. Phys. Chem. 1962;66:561–562. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson AR, O'Sullivan B, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:2652–2660. doi: 10.1021/ic991471t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen SM, Meyer M, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;120:6277–6286. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huheey JE, Keiter EA, Keiter RL. Inorganic Chemistry: Principles of strcuture and reactivity. 4th ed. HarperCollins College; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.using the equation: and data collected at [Conc] = 2.16 × 10−6 M, which gave values of Ssignal =1.73 × 106 cps, Sblank ≅ 1000 cps, noise(rms) = 200 cps and hence an MDC of 4.99 × 10−11 M.

- 24.Latva M, Takalo H, Mukkala V-M, Matachescu C, Rodriguez-Ubis JC, Kankare J. J. Lumin. 1997;75:149–169. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beeby A, Clarkson IM, Dickins RS, Faulkner S, Parker D, Royle L, Sousa ASd, Williams JAG, Woods M. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1999;2:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 26. http://www.lumiphore.com.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.