Abstract

Screening for effective therapeutic agents from millions of drug candidates is costly, time-consuming and often face ethical concerns due to extensive use of animals. To improve cost-effectiveness, and to minimize animal testing in pharmaceutical research, in vitro monolayer cell microarrays with multiwell plate assays have been developed. Integration of cell microarrays with microfluidic systems have facilitated automated and controlled component loading, significantly reducing the consumption of the candidate compounds and the target cells. Even though these methods significantly increased the throughput compared to conventional in vitro testing systems and in vivo animal models, the cost associated with these platforms remains prohibitively high. Besides, there is a need for three-dimensional (3D) cell based drug-screening models, which can mimic the in vivo microenvironment and the functionality of the native tissues. Here, we present the state-of-the-art microengineering approaches that can be used to develop 3D cell based drug screening assays. We highlight the 3D in vitro cell culture systems with live cell-based arrays, microfluidic cell culture systems, and their application to high-throughput drug screening. We conclude that among the emerging microengineering approaches, bioprinting holds a great potential to provide repeatable 3D cell based constructs with high temporal, spatial control and versatility.

Keywords: Drug screening, high-throughout, microengineering, cell array, pharmaceutical research

1. Introduction

Advances in combinatorial chemistry has allowed the emergence of chemical libraries consisting of millions of compounds [1]. Drug development process involves testing the metabolic function and toxicity of these compounds to determine therapeutic efficacy and risk potentials [2, 3]. Although animal models are commonly used for drug development and pharmacokinetic studies, animal use in research is generally associated with significantly high cost, time and labor-intensive processes, and facing ethical concerns [4-7]. Cells patterned in an array format (i.e., cell microarray) hold great potential in screening drug candidates for efficacy and toxicity at high throughput [8]. Recent studies have demonstrated that in vitro cell microarrays can prove to be effective in drug screening applications (e.g., libraries from SPECS and Enamine) with reduced cost and time by significantly reducing the need for animal testing studies [8-11]. These microarrays enable cell analysis such as drug treatment response, cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions in a high-throughput manner (hundreds to thousands of samples on a single glass slide) [8, 11-18].

Three-dimensional (3D) cell microarrays provide an alternative to conventional two-dimensional (2D) multiwell plate based assays. 3D cell culture mimicking native ECM enables researchers to define structure-function relationships and to model cellular events and disease progression [19-23]. For example, tumor cells cultured on 2D and 3D cultures show different cell morphology [24], metabolic characteristics (e.g., increased glycolysis of osteosarcoma cells in 3D culture, differences in the lactate and alanine levels) [22, 25], and drug response [26]. Several methods have been developed to form 3D cell constructs such as spontaneous cell aggregation, liquid overlay cultures, rotation and spinner flask spheroid cultures, microcarrier beads, rotary cell culture systems and scaffold-based cultures [27]. Recently, spheroid-based drug screening methods have emerged [28]. However, it is challenging to form 3D cell microarrays using these methods. In contrast, emerging microengineering technologies enable versatile fabrication of 3D cell-based microarrays including soft lithography, surface patterning, microfluidic-based manipulation and cell printing.

In vivo, cells are in a microenvironment that usually consists of multiple cell types precisely organized in 3D. For instance, tumors are complex tissues composed of, in the case of carcinomas, both cancer cells and stromal cells such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells [29, 30]. These stromal cells are a key determinant in the malignant progression of cancer (e.g., angiogenesis [29], metastasis [31], invasiveness [32]) and represent an important target for cancer therapies [33]. However, the specific contributions of these stromal cells to tumor progression are poorly defined and many of the underlying mechanisms remain poorly exploited [34]. The spatial position of cells are also important for their functionality which is regulated by the cell's genetic coding and its communication with neighboring cells [35]. A method that precisely positions cells forming 3D co-culture models at large number in a repeatable manner (i.e., a co-culture array) is helpful to understand the interaction between different cell types such as to understand cancer pathogenesis and to improve current therapies. In spite of the importance of cell co-culture and advances in surface patterning and microfluidic techniques, a controlled arrangement of multiple cell types in an array format is challenging.

In this review, we report the state-of-the-art advances in microengineering methods to fabricate cell microarrays and describe existing methods used to introduce drugs to cell microarrays for drug screening applications. Among these emerging fabrication methods, cell printing holds great potential to provide highly repeatable 3D tissue constructs, since it can control the cell positions temporally and spatially.

2. 3D cell culture vs. 2D cell culture

It has been shown that when cells are cultured in 2D monolayers, significant perturbations in gene expression are observed compared to cells in native tissues and in 3D culture conditions [36]. Furthermore, 3D cellular constructs can mimic the native tissue microenvironment and hence better emulate the drug responses observed in animal models compared to 2D monolayer cell cultures [24, 37, 38]. In vivo, cells are imbedded in 3D ECM with ligands such as collagens and laminins that allow cell-cell communication between neighboring cells [39, 40]. Furthermore, expression of genes responsible for angiogenesis, chemokine generation, cell migration and adhesion differs in 3D and 2D cultures [25, 27]. For example, β1-integrin and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGRF) in malignant human breast epithelial cells are over-expressed when cultured in 3D matrix, but not in 2D monolayers [27]. In addition, tyrosine phosphylation, which plays a role in signaling of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), is down regulated in 3D culture [41]. Additionally, cancer cells show different responses to anti-cancer agents in 3D culture. Mouse mammary tumor cells have greater drug resistance to melphalan and 5-fluorouracil in a 3D collagen matrix as compared to 2D controls [42]. Anti-mitotic drugs (doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil) become effective after 24 hours of treatment in 2D cell culture (SA87, NCI-H460 and H460M tumor cell lines), whereas they cannot show efficacy until one week later in hyaluronic acid (HA) based 3D culture [43]. Furthermore, co-culture of endothelial, stromal, and/or epithelial cells has been achieved within 3D systems, which allows to study side effects of a drug on neighboring stromal cells [25]. So far, accumulative evidence demonstrates that in vitro 3D culture can better recapitulate in vivo cellular response to drug treatment than 2D culture, and has potential to be a superior platform for drug development. Based on these observations, it can be suggested that cellular responses to drug candidates observed in 2D may not be applicable to in vivo response. Therefore, there is a need for in vitro 3D cell culture models which would bridge the 2D monolayer cell culture systems and the complex animal models [18, 19, 38, 44-46].

3. Microengineering methods to fabricate cell microarrays

In this section, we will describe the existing methods which have been developed to fabricate cell microarrays, including microwell-based methods, surface patterning methods, microfluidic methods, and cell printing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of different methods for fabricating cell microarray

| Fabrication methods | Throughput | Cell co-culture capability | Control over cell density | 3D capability | Single cell array capability | Relevant References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwell | Medium | Yes | Low | Yes | Yes | [13, 125] |

| Surface patterning | Medium | Yes | Medium | Yes# | Yes | [55-58, 126, 127] |

| Microfluidics | Medium | Yes | Low | Yes | Yes | [68, 70, 71] |

| Cell printing | High | Yes | High | Yes | Yes | [77, 87, 94, 95, 128] |

3.1. Microwell-based method to fabricate cell microarrays

With advances in microengineering such as microfabrication and soft lithography, a high-density array of wells with microscale well sizes (e.g., tens to hundreds of micrometers) can be fabricated. When these wells are loaded with cells via cell seeding due to gravity, cells immobilized inside these microwells form cell microarrays.

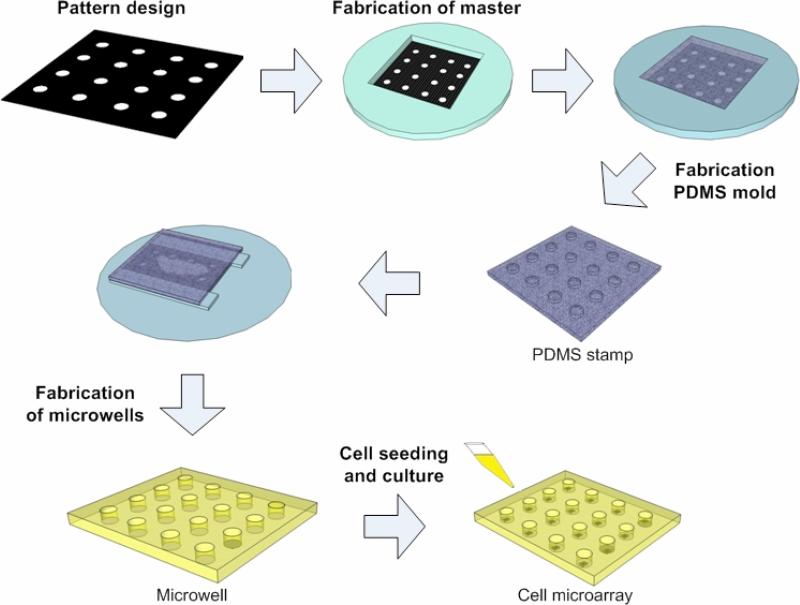

Soft lithography has gained popularity in common laboratory settings because of low-cost, and compatibility with a broad range of materials. In principle, five steps are involved to create cell arrays using microwells, including pattern design, fabrication of a photomask and a master, fabrication of PDMS stamps, fabrication of microwells, loading cells of interest onto microwells (Figure 1). Generally, a silicon wafer is used as a substrate, on which a photosensitive, thin film (e.g., SU-8) is placed. Once the film is exposed to UV light through a designed photomask, the film becomes solidified with a permanent microstructure created on the silicon wafer. The silicon wafer mold can be used repeatedly as a microstructure master for casting polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps, which can be prepared by mixing PDMS prepolymer, thermally curing the polymer, and peeling the resulted flexible and transparent films. The casted PDMS stamp is then used to prepare microwell arrays on a glass slide. Using this method, Moeller et al. generated a microwell array with a high resolution of 20,000 dpi, which enables fabrication of microwell arrays with seeded cells at a greater density [47]. Due to the 3D microenvironment on microwell arrays, mouse embryonic cells aggregate within microwells and form homogeneously sized embryoid bodies (EBs) [48].

Figure 1. Schematic illustrations of fabricating cell microarrays using soft lithography.

Generally, pattern is designed and a photomask is fabricated based on design. The mask is then used to fabricate the master on a silicon wafer via lithography. The silicon wafer master can be used repeatedly as a mold for casting PDMS stamps. The PDMS stamp containing protruding columns is pressed onto another hydrogel solution (e.g., PEG monomer solution) on a glass slide. Microwells array is formed by UV cross-linking of PEG and removing the PDMS stamp from the formed microwells. Cells are seeded to microwells to form cell microarrays.

Although PDMS has been widely used in biomedical engineering, it is restricted by innate hydrophobicity, absorption of organic solvents and small molecules, and water evaporation [49]. Alternatively, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and agarose can be used to fabricate microwells instead of PDMS [48, 50-52]. For example, Karp et al. showed that homogenous and controllable EBs were formed within microfabricated PEG microwells, which can be used for high-throughput screening of drug candidates [48].

The shape and dimension of microwell arrays can be defined according to photomask micropattern to control the size and shape of cell aggregates in the wells [53]. By varying the size, shape and depth of microwells, single cell arrays can be fabricated to evaluate cellular behavior at a single cell level, which may be absent in cell aggregate [13]. High-throughput measurements of single cell responses are thus essential for a variety of applications including drug screening, toxicology and cell biology [54]. However, microwell method based on soft lithography has limited flexibility in changing pattern design due to reliance on photomasks.

3.2. Surface patterning for cell microarrays

Surface patterning is commonly used to prepare cell microarrays, where material surface (generally a cell-resistant surface) is modified locally in an array pattern with cell adhesive biomolecules (e.g., collagen, laminin, fibronectin). When cells are seeded onto the surface, they will attach only to the patterned area modified with biomolecules of high affinity to cells forming cell microarrays [14].

Via surface patterning method, Flaim et al. prepared a cell microarray to study the effects of different combinatorial matrices of ECMs on the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [55]. In this study, 32 different ECM combinations were spotted onto a polyacrylamide gel coated glass slide using a standard DNA spotter (pin printing). Mouse ESCs can only attach to ECM-coated areas, resulting in an ECM-based cell microarray, which allows the investigation of cell-ECM interactions in a high-throughput manner. Similarly, Ceriotti et al. microarrayed ECM proteins (e.g., fibronectin) on plasma-deposited polyethyleneoxide (PEO-like) film coated glass slides [56]. In another study, Anderson et al. developed a nanoliter scale platform synthesizing biomaterial libraries in an array format with the aid of a robotic liquid handling system [57]. With this method, 1,700 cellular-material interactions were simultaneously investigated on a single glass slide.

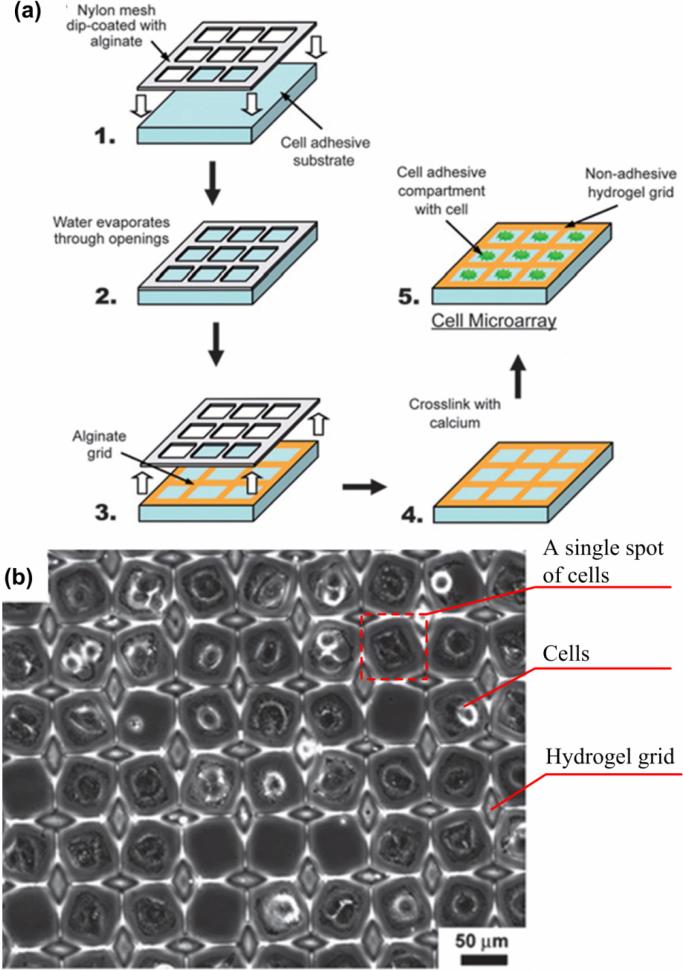

Recently, Zawko et al. developed an inexpensive, off-the-shelf surface patterning method (Figure 2) to fabricate cell microarrays [58]. The method is based on micropatterning of 3D alginate grids on glass slides using a woven nylon mesh, eliminating the lithography step. The hydrogel grids were used to guide cell seeding on a glass slide to form cell microarrays at a density of 21,000 spots/cm2 (single cell array) or 6,000 spots/cm2 (multi-cellular array).

Figure 2. Fabrication of a cell microarray using surface patterning [58].

(a) Alginate dip-coated in a Nylon mesh is stamped on a cell adhesive substrate (e.g., glass). Alginate is crosslinked after water evaporation with a solution of calcium chloride forming hydrogel spots. The cell microarray is achieved by seeding cells within the hydrogel compartments. (b) A fibroblast array with density of 21,000/cm2 was achieved using this method (24 hours in culture).

3.3. Microfluidic methods

Microfluidics has emerged as a promising technology with widespread applications in engineering, biology and medicine [59, 60]. Microfluidics offers special advantages for manipulating cells since local cellular microenvironment can be controlled [61]. Cell microarrays containing multiple cell types have been fabricated using microfluidic methods [62-65].

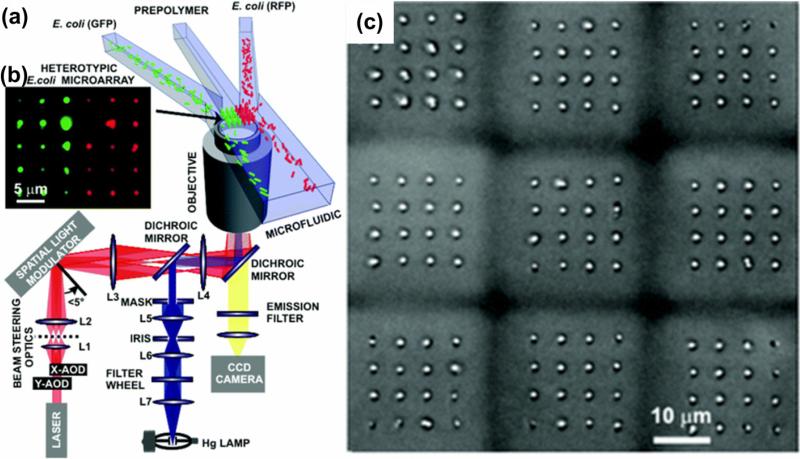

Meyvantsson et al. developed compartmentalized microfluidic cell arrays with a high density (up to 768 micro-chambers in a 128 × 86 mm2 area) [66]. In this array, cells in 2D or 3D microenvironment were cultured via droplet-based passive pumping with maintained basic microfluidic operations including routing, compartmentalization and laminar flow. The use of external tubing and valves to control the liquid flow was avoided because of direct access to individual elements via holes in the microfluidic channel surface. This design offers the advantage of reducing the device volume and minimalizing dead volumes. In another study, Wang et al. developed a microfluidic cell array with individually addressable chambers controlled by pneumatic valves for cell culture and cell-reagent response [63]. In this cell array, different types of cells can be directed into designated chambers for culture and observation. Mirsaidov et al. fabricated a 3D co-culture cell microarray by integrating microfluidics and timeshared holographic optical trapping (Figure 3) [62]. In this method, E. coli cells were manipulated using 3D arrays of optical traps, and then conveyed to an assembly area using a microfluidic network (Figure 3a). In the assembly area, the cells were encapsulated and assembled in a small volume (30 × 30 × 45 μm3) of PEG (Figure 3b). This step was repeated to form cell microarrays (Figure 3c). However, the optical trapping force is dependent on laser power which may affect cell viability [62], which limits the maximum area of the array (350 × 350 μm2). In addition, Wu et al. formed a microfluidic platform allowing self-assembly of spheroids of tumor cells and characterized the dynamics of spheroid formation [67]. In this study, U-shape traps which have inner volume of 35 × 70 × 50 μm3, were designed and integrated in the microfluidic array device. It was observed that MCF-7 breast cancer cells formed spheroids (7,500 spheroids per cm2) with a narrow size distribution (10 ± 1 cells per spheroid). The perfusion of cell media allows for prolonged cell culture period, which can be potentially used to evaluate anti-cancer drugs in a high-throughput manner [67].

Figure 3. Fabrication of a cell microarray using microfluidic methods [62].

(a) Time-multiplexed, 3D arrays of optical traps were used to manipulate cells. The optical traps were created using infrared light (red path) from a Ti:sapphire laser beam. A microfluidic network is used to deliver the multiple types of cells mixed with hydrogel precursor to the assembly area: two types of cells (E. coli RFP, E. coli GFP) flow in different channels with a third cell-free channel in middle. In the assembly area, the cells are encapsulated within the hydrogel through photo crosslinking forming cell array (b, 2D 5 × 6 microarray). (c) Nine homogeneous 4 × 4 microarrays of G1 E. coli forming a 3 × 3 microarray.

Microfluidic technologies have also been used to fabricate single-cell microarrays [68-70]. Kaneko et al. developed a cell microarray loaded with single cardiomyocytes which were interconnected via microfluidic channels [69]. With this cell microarray, it is found that cell–cell communication affects cell response to drug treatment. Recently, Xu et al. designed a microfluidic single-cell microarray for testing drug response of individual cells [70]. The array consisted of 8 parallel channels with 15 cell-docking units in each channel. This design enabled simultaneous monitoring of the cellular responses exposed to various drug candidates (e.g., specific activators and inhibitors of the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels) in multiple microchannels. Moreover, combinations of hydrogels and microfluidics have been used to fabricate 3D cell microarrays, which may provide new methods for drug screening in a physiologically relevant environment. For example, Tan and Takeuchi developed a bead-based dynamic 3D cell microarray by introducing cell encapsulating alginate beads into a microfluidic system, and arraying the beads using a fluidic trap [71].

3.4. Cell printing

Cell printing is an emerging technique [72] and has been used to fabricate 2D or 3D cell microarrays. Cell printing is different from other cell microarray approaches described above in several ways, (i) Cell printing is automated through computer-control enabling high-throughput manufacturing of cell arrays with high spatial resolution and control [73, 74], e.g., the dimensions of the array and spot-to-spot distances can be altered, (ii) Cell printing can place different types of cells onto intended positions (spatial control) by switching multiple ejecting nozzles temporally [75], (iii) 3D cell models can also be fabricated using cell printing [76-78], (iv) Cell printing has been shown to produce repeatable and uniform 3D cell aggregates and constructs [75, 78]. Current cell printing and deposition techniques include inkjet printing [79, 80], laser printing [73, 81], bio-electrosprays (BES) [82], and cell spotting [83, 84]. However, there are challenges with existing cell printing technologies such as low cell viability, loss of cellular functionality and clogging of ejectors. Recently, several improved droplet generation methods were introduced [85-89]. Acoustic cell printing technologies have been developed to deposit cells and polymers that are sensitive to heat, pressure and shear [87, 90-94]. Alternatively, valve-based printing has been used to print cell-encapsulating hydrogels [95], single cells for RNA analysis [96] and blood cells for blood cryopreservation [97, 98]. These technologies have advantages over existing printing technologies in terms of higher cell viability and functionality [94, 99].

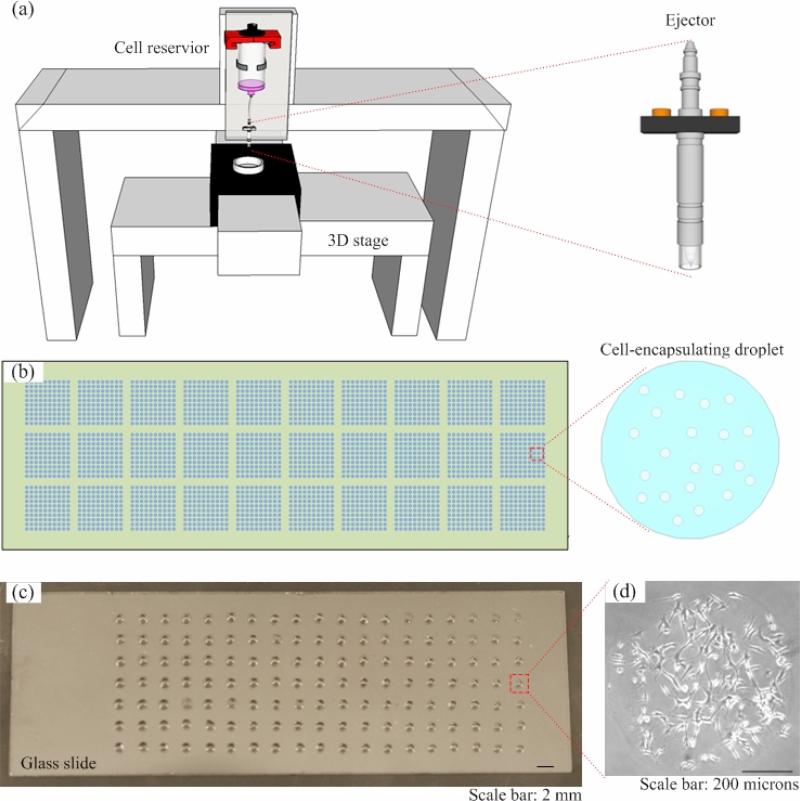

Hart et al. [83] used a robotic microarray spotting device (pin printing) to print cells onto streptavidin-coated slides in an array format. With this method, high density has been achieved with~4,700 discrete HeLa cells printed on a single slide using an 8-ejector printer. Recently, cell printing has been used to directly deposit cell-laden scaffolding materials (e.g., ECM materials such as collagen, alginate, elastin, and agarose) onto glass surfaces at high throughput to 3D cell microarrays (e.g., Figure 4) [95, 100, 101]. The scaffolding materials can support cells mechanically and allow for perfusion of nutrients, thus enabling long-term cell culture [102-104]. For example, cells can be encapsulated in nanodrops of collagen or alginates, which are mounted onto a functional glass slide by a robotic system to form 3D cell microarrays [57, 84, 105]. The same bioprinting platform can then be used to deliver the drug candidates into the cell arrays in a controllable and at high throughput. Therefore, bioprinting technology offers a versatile method for both forming the 3D cell arrays followed by compound delivery and testing.

Figure 4. Fabrication cell microarray using cell printing method.

(a) Schematic of a printing system. A valve-based ejector is connected with a 3D stage which offers ejection of cell encapsulating droplets (e.g., hydrogels) high spatial resolution. (b) The droplets can be pattend in an array format on a substrate (e.g., Petri dish, glass slides). (c) A sample of high-density cell microarrays.

4. Methods for adding drugs into cell-based assays

Controlled delivery of drug candidates into cell microarrays is the key to successful drug screening (i.e., decreased failure rate) at high throughput. A direct way is to load drug candidates to each spot using a robotic system (e.g., Perkin Robot Loading System). However, loading thousands of chemicals to cell microarrays usually takes hours and even days, which significantly affect the viability of cells during the loading process and the reproducibility of cell-to-drug responses. In addition, it is essential to introduce chemical or genomic stimuli to each cell spot and avoid cross-contamination between thousands of wells on the cell microarray. To address these technical difficulties, various methods have been developed to efficiently deliver drugs to cell microarrays, including drug patterning [106], stamping [107], microfluidic drug loading [108] and aerosol sprays [109, 110]. These methods differ in throughput, compatibility with co-culture arrays, and control over the cell density (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of different methods to add drugs to cell-based assays

4.1. Drug patterning

Drug patterning utilizes a printing robot to array chemicals on a substrate. When cells are seeded on the top of this chemical loaded substrate, only cells on the each arrayed dot are affected and then form affected-cell array. Since Drug patterning does not need print cells, the method is easily to be utilized in high-throughput drug screening. For example, Bailey et al. developed a drug patterning method to screen for small molecular compounds using mammalian cells at high throughput [106]. In this system, small molecular compounds were encapsulated in scaffold made of poly-(D), (L)-lactide/glycolide copolymer (PLGA). On a Nichelated slide, small molecular compounds were spotted (pin printing). Cells were then seeded on top of these spots to form a monolayer of cells. Since compounds encapsulated in the PLGA matrix can slowly diffuse to attached cells, the dose-response can be plotted as a function of distance to the spot center. It was observed that reduced expression of tuberous sclerosis complex gene 2 (TSC2), which was achieved by transient RNAi, highly correlated to the resistance of cells to a compound, mactecin II. Combined with imaging-based readouts, the drug patterning method consumed small amounts of test compounds and few cells compared to microplate-based screening methods. However, the diffusion of gradually released drugs can cause crosstalk between neighboring spots, thus limiting the cell densities.

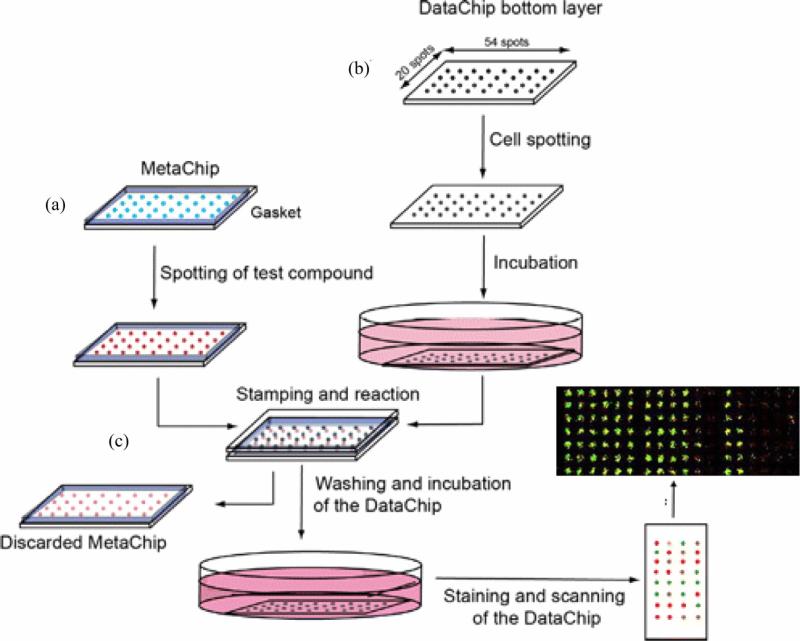

4.2. Stamping method

Stamping method includes two chips, one is a cell chip on which cells are arrayed, and the other is a drug chip. When high-throughput screening is initiated, chemicals are spotted on a drug chip and then stamped onto a cell chip. The stamping method makes it possible that thousands of screening experiments are performed on a single glass slide. For example, Lee et al. developed a simple cell array based stamping method to evaluate the drug metabolic process in vivo, which is mainly mediated by enzyme P450 in liver cells, at high throughput [84, 107]. This stamping method is consisted of three major steps, including fabrication of cell arrays, drug loading (stamping) and data analysis (Figure 5). Initially, an array chip (metachip) containing human P450 and prodrugs is prepared. The selected prodrugs can be cyclophosphamide, tegafur and acetaminophen, which were the substrate of P450. When spotted on the array (pin printing), prodrugs were digested by P450, generated metabolites, mimicking the metabolism of prodrugs in vivo. Meanwhile, 3D cell aggregate array were prepared by spotting collagen solution containing MCF-7 breast cancer cells onto collagen-modified slides. Upon stamping, metabolites of prodrugs from the chip can diffuse into 3D cell aggregate array and affect cell proliferation. Monitoring of biological events on the cell array allows evaluating the bioactivity/toxicity of prodrug metabolites. Wu et al. developed a stamping method suitable for screening drug-drug interactions in cell-based assays [52]. This stamping method includes drug combination chip and cell chip. Drug combinations were printed on a PDMS post array and stamped to the cell-seeded microwells. In this way, drug combination effects were evaluated in the sealed chamber, and three chemicals were found to have the drug-drug interactions with verapamil. The stamping method offers opportunities for rapid and inexpensive combinatorial drug screening to the common research lab. This cell array based stamping method is simple and rapid, significantly reducing the complexity of drug loading to cell array and thus improving the throughput [84].

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of drug loading using stamping method [84].

The stamping method consists of three main steps to achieve precise drug loading. (a) Compounds of interest are spotted on an array chip (Metachip). (b) Cells are grown on a PDMS base, defined as a cell array (DataChip). (c) The array chip and DataChip are stamped together to allow for perfusion. The toxicity of compounds on cells is evaluated using live/dead staining on the cell array. Each cell spot has diameter of 600 μm.

4.3. Microfluidic drug loading

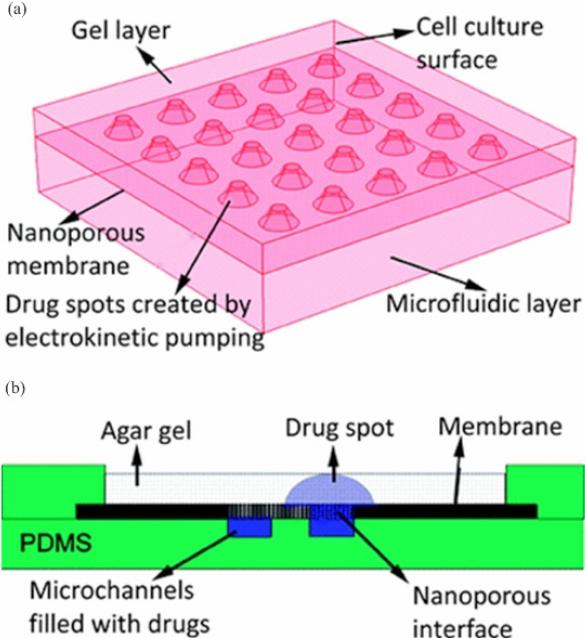

Methods based on microfluidics have also been developed to deliver drugs onto high-throughput drug screening platforms. For instance, Hung et al. fabricated a PDMS microchamber containing 10×10 arrays as a drug screening platform on which long term cell culture is enabled [111]. The microchamber is surrounded with microchannels to exchange medium and load reagents for biochemical assays. HeLa cells are introduced into the microchamber by a syringe and continuous perfusion of medium through these microfluidic channels enables long-term cell culture at 37 °C. However, this method has some drawbacks such as inhomogeneous cell distribution in the 10×10 arrays and challenges in further miniaturization of the device. In another study, Upadhyaya et al. developed a microfluidic device to control drug supply in a cell-based microarray for high-throughput screening [108]. This device consists of three layers, an agar gel to support adherent cell culture, a micropatterned nanoporous membrane layer and a PDMS layer containing two microfluidic channels (Figure 6). Compounds of interest can be loaded into the microchannel and then spatially distributed via an electrical field into the agar gel through the nanoporous membrane. By controlling the electric field across the nanoporous membrane, microscale drug spots with the diameter as small as 200 μm can be obtained with inter-spot distances ranging from 0.4-1 mm. In both studies, microfluidics drug delivery has been demonstrated, with potential to enable long-term evaluation of drug-cell interactions at high throughput [108, 111].

Figure 6. Schematic of the microfluidic device for high-throughput drug loading [108].

(a) This device consists of three layers, a gel layer to support adherent cell culture, a micropatterned nanoporous membrane layer and a microfluidic layer made by PDMS. (b) Compounds of interest can be loaded into the microchannel patterned on PDMS layer and spatially located into the gel layer through the nanoporous membrane upon an electric field.

4.4. Aerosol spray

To load protein solution on a chemical array simultaneously, aerosol spray is an efficient way. In this method, thousands of chemicals are first arrayed on a substrate and then protein solution is sprayed on them. Then chemicals are reacted with protein solution simultaneously and ultra-high-throughput screening can be performed. For example, protein microarrays are often used to evaluate the interactions between chemicals and enzymes. However, immobilization of chemicals onto glass slides in an array format is time consuming and often leads to protein-degradation [112, 113]. Furthermore, it is challenging to rapidly deliver droplets to each spot without evaporation and causing cross-contamination. To address these challenges, Gosalia et al. established a platform for enzymatic reactions in nanoliter liquid phase [109]. In this method, a library of 352 compounds was microarrayed in glycerol droplets on 10 glass slides at a density of 400 spots/cm2. Biological samples such as caspases 2, 4 and 6, thrombin and chymotrypsin were aerosolized and sprayed onto the drug microarray using an ultrasonic nozzle. Enzymatic reactions were carried out by subsequent spraying the drug microarray with nanoliters of reagents, significantly reducing the consumption of materials and reagents. Similarly, Ma et al. also used the spray strategy to achieve ultra-high-throughput drug screening [110]. Via this strategy, over 6,000 homogeneous reactions per 1 × 3 inch2 microarray were carried out, which significantly reduced the amount of reagents used (1 nl) by >10,000-fold compared to the 384-well plate assays (10 μl). This technique is compatible with many conventional well-based reactions and can be carried out using instruments available in industrial and academic institutions, such as liquid handlers, DNA microarrayers, chip scanners and data analysis software. Hence, this spray method can be simply implemented to achieve high-throughput drug screening without the need for sophisticated equipment.

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Identifying millions of drug candidates for disease treatment is costly and time-consuming with current drug-screening technologies such as the multiwell-plate based screening method. Cell-based microarrays have recently been employed to address the challenges associated with conventional microwell plate based methods for high-throughput drug screening applications. Cell microarrays have been broadly used as a biological tool to study target selection, drug candidate identification as well as preclinical test and drug dosage optimization [114, 115]. Current microarray fabrication methods include soft lithography, surface patterning, microfluidic methods and cell printing, which provide a platform to studying cell responses to different treatments (e.g., drug screening, cytotoxicity screening) in a high-throughput manner. These methods can increase the throughput with significantly reduced cost spent on amounts of expensive test reagents and materials (e.g., chemical compounds, cells) are needed [16]. However, as the number and types of cells to control increases, tracking these cells in microchannels with multiple valving steps require a complex peripheral system before and after sorting, as the cells need to travel and be spatially patterned at a specific location as some of the existing applications require. These emerging cell-based methods are broadly applicable and can be extended to applications such as assessing stem cell differentiation, characterizing interactions between cells and their microenvironment, and analyzing genomic functions by RNAi.

There are several challenges associated with cell microarrays as high-throughput drug screening methods. One of the main challenges is efficient loading of drug candidates into the cell microarrays. Several methods have been developed to address this challenge, including drug patterning, stamping, microfluidic drug loading and aerosol spray methods. Although these methods enable the application of cell microarrays in high-throughput drug screening, there remains unaddressed challenges. For example, an ideal polymer is needed to maintain biological and chemical properties of various drug candidates in drug patterning methods. Also, in stamping and aerosol spray methods, tests are generally performed in the same fluid medium limiting the range of experimental conditions that can be attained (i.e., lack of compartmentalization) and cross-contamination between neighboring spots always exists which limits the cell density. Therefore, further advances are needed to develop efficient techniques to load drugs into microarrays without cross-contamination. Cell printing holds great potential to address this challenge and could be used for drug loading, as it has been utilized to load growth factors and other biomolecules with or onto cells [116-118]. Another challenge is to form 3D cell arrays. For instance, only limited human tumor cell lines (<100) can form and grow in 3D spheroid format in vitro, which is a typical native cancer structure [119]. Although it is able to form cellular constructs in 3D with existing methods in an array format (e.g., microwells, microfluidics, printing), further studies are needed to verify that these constructs show similar, if not the same, response to drug treatment. For instance, the existing in vitro platforms of 3D cellular models are not relevant to most human cancers in vivo (e.g., cancers of the blood) [120]. In addition, screening cell response to drugs at high-throughput (e.g., via imaging) and analysis of such large amount of screening data are also challenging. This may become a major bottleneck for drug screening applications [121]. With advances in microscopy and corresponding image analysis techniques [122-124], cell microarrays and emerging drug loading techniques, especially bioprinting, holds a great potential to provide highly repeatable 3D cellular constructs that could be a powerful tool for studying cell-drug response in a high-throughput manner.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by R21 (AI087107), and the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology under U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity Cooperative Agreements DAMD17-02-2-0006, W81XWH-07-2-0011, and W81XWH-09-2-0001. Also, partially this research is made possible by a research grant that was awarded and administered by the U.S. Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC) and the Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC), at Fort Detrick, MD. The information contained herein does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

References

- 1.Geysen HM, et al. Combinatorial compound libraries for drug discovery: an ongoing challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(3):222–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano KA, Haskins JR, Taylor DL. Advances in high content screening for drug discovery. Assay and Drug Development Technologies. 2003;1(4):565–577. doi: 10.1089/154065803322302826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littman BH, Williams SA. Opinion: The ultimate model organism: progress in experimental medicine. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2005;4(8):631–638. doi: 10.1038/nrd1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennings M, Silcock S. Benefits, necessity and justification in animal research. Atla-Alternatives to Laboratory Animals. 1995;23(6):828–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebonvallet N, et al. The evolution and use of skin explants: potential and limitations for dermatological research. European Journal of Dermatology. 2010;20(6):671–684. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitra A, Wu Y. Use of In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) to facilitate the development of polymer-based controlled release injectable formulation. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2010;4(2):94–104. doi: 10.2174/187221110791185024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster J, et al. Ethical implications of using the minipig in regulatory toxicology studies. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2010;62(3, Sp. Iss. SI):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarmush ML, King KR. Living-cell microarrays. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;11:235–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starkuviene V, Pepperkok R, Erfle H. Transfected cell microarrays: an efficient tool for high-throughput functional analysis. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4(4):479–89. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen DS, Davis MM. Molecular and functional analysis using live cell microarrays. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gidrol X, et al. 2D and 3D cell microarrays in pharmacology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9(5):664–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camp RL, Neumeister V, Rimm DL. A decade of tissue microarrays: progress in the discovery and validation of cancer biomarkers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(34):5630–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roach KL, et al. High throughput single cell bioinformatics. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25(6):1772–9. doi: 10.1002/btpr.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hook AL, Thissen H, Voelcker NH. Advanced substrate fabrication for cell microarrays. Biomacromolecules. 2009 doi: 10.1021/bm801217n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes TG, et al. High-throughput cellular microarray platforms: applications in drug discovery, toxicology and stem cell research. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(6):342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castel D, et al. Cell microarrays in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11(13-14):616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angres B. Cell microarrays. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2005;5(5):769–79. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.5.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giese K, et al. Unravelling novel intracellular pathways in cell-based assays. Drug Discovery Today. 2002;7(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)02126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada KM, Cukierman E. Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell. 2007;130(4):601–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutmacher DW. Biomaterials offer cancer research the third dimension. Nat Mater. 2010;9(2):90–3. doi: 10.1038/nmat2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feder-Mengus C, et al. New dimensions in tumor immunology: what does 3D culture reveal? Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(8):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheema U, et al. Spatially defined oxygen gradients and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in an engineered 3D cell model. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(1):177–86. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souza GR, et al. Three-dimensional tissue culture based on magnetic cell levitation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(4):291–6. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abu-Yousif AO, et al. PuraMatrix encapsulation of cancer cells. J Vis Exp. 2009;(34) doi: 10.3791/1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurski LA, et al. 3D Matrices for anti-cancer drug testing and development. Oncology. 2010 January/February; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong W, et al. In vivo high-resolution fluorescence microendoscopy for ovarian cancer detection and treatment monitoring. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(12):2015–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J. Three-dimensional tissue culture models in cancer biology. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2005;15:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedrich J, et al. Spheroid-based drug screen: considerations and practical approach. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(3):309–24. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121(3):335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Z, Nor JE. Transcriptional targeting of tumor endothelial cells for gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(7-8):542–53. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karnoub AE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449(7162):557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studebaker AW, et al. Fibroblasts isolated from common sites of breast cancer metastasis enhance cancer cell growth rates and invasiveness in an interleukin-6-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2008;68(21):9087–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(5):392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orimo A, Weinberg RA. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer: a novel tumor-promoting cell type. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(15):1597–601. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anghelina M, et al. Monocytes/macrophages cooperate with progenitor cells during neovascularization and tissue repair-Conversion of cell columns into fibrovascular bundles. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:529–541. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birgersdotter A, Sandberg R, Ernberg I. Gene expression perturbation in vitro - A growing case for three-dimensional (3D) culture systems. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2005;15(5):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin KJ, et al. Prognostic breast cancer signature identified from 3D culture model accurately predicts clinical outcome across independent datasets. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunz-Schughart LA, et al. The use of 3-D cultures for high-throughput screening: The multicellular spheroid model. Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 2004;9(4):273–285. doi: 10.1177/1087057104265040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2009;103(4):655–663. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhadriraju K, et al. Engineering Cell Adhesion. In: Ferrari M, Desai T, Bhatia S, editors. BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology. Springer; US: 2007. pp. 325–343. 343. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cukierman E, et al. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294(5547):1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller BE, Miller FR, Heppner GH. Factors Affecting Growth and Drug Sensitivity of Mouse Mammary Tumor Lines in Collagen Gel Cultures. Cancer Research. 1985;45(9):4200–4205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.David L, et al. Hyaluronan hydrogel: An appropriate three-dimensional model for evaluation of anticancer drug sensitivity. Acta Biomater. 2008;4(2):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang S. Beyond the Petri dish. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):151–2. doi: 10.1038/nbt0204-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pampaloni F, Reynaud EG, Stelzer EHK. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(10):839–845. doi: 10.1038/nrm2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurkan UA, Gargac J, Akkus O. The Sequential Production Profiles of Growth Factors and their Relations to Bone Volume in Ossifying Bone Marrow Explants. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2010;16(7):2295–2306. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moeller HC, et al. A microwell array system for stem cell culture. Biomaterials. 2008;29(6):752–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karp JM, et al. Controlling size, shape and homogeneity of embryoid bodies using poly(ethylene glycol) microwells. Lab Chip. 2007;7(6):786–94. doi: 10.1039/b705085m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukhopadhyay R. When PDMS isn't the best. Analytical Chemistry. 2007;79(9):3248–3253. doi: 10.1021/ac071903e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshimoto K, Ichino M, Nagasaki Y. Inverted pattern formation of cell microarrays on poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) gel patterned surface and construction of hepatocyte spheroids on unmodified PEG gel microdomains. Lab Chip. 2009;9(9):1286–9. doi: 10.1039/b818610n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang G, et al. Agarose microwell based neuronal micro-circuit arrays on microelectrode arrays for high throughput drug testing. Lab Chip. 2009;9(22):3236–42. doi: 10.1039/b910738j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu J, et al. A sandwiched microarray platform for benchtop cell-based high throughput screening. Biomaterials. 2011;32(3):841–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi YY, et al. Controlled-size embryoid body formation in concave microwell arrays. Biomaterials. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rettig JR, Folch A. Large-scale single-cell trapping and imaging using microwell arrays. Anal Chem. 2005;77(17):5628–34. doi: 10.1021/ac0505977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flaim CJ, Chien S, Bhatia SN. An extracellular matrix microarray for probing cellular differentiation. Nat Methods. 2005;2(2):119–25. doi: 10.1038/nmeth736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ceriotti L, et al. Fabrication and characterization of protein arrays for stem cell patterning. Soft Matter. 2009;5(7):1406–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson DG, Levenberg S, Langer R. Nanoliter-scale synthesis of arrayed biomaterials and application to human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(7):863–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zawko SA, Schmidt CE. Simple benchtop patterning of hydrogel grids for living cell microarrays. Lab Chip. 2010;10(3):379–83. doi: 10.1039/b917493a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee WG, et al. Nano/Microfluidics for diagnosis of infectious diseases in developing countries. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(4-5):449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442(7101):368–73. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marimuthu M, Kim SH. Microfluidic cell co-culture methods for understanding cell biology, analyzing bio/pharmaceuticals and for developing tissue constructs. Anal Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mirsaidov U, et al. Live cell lithography: using optical tweezers to create synthetic tissue. Lab Chip. 2008;8(12):2174–81. doi: 10.1039/b807987k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang HY, Bao N, Lu C. A microfluidic cell array with individually addressable culture chambers. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24(4):613–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paguirigan AL, Beebe DJ. From the cellular perspective: exploring differences in the cellular baseline in macroscale and microfluidic cultures. Integr Biol (Camb) 2009;1(2):182–95. doi: 10.1039/b814565b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gomez-Sjoberg R, et al. Versatile, fully automated, microfluidic cell culture system. Anal Chem. 2007;79(22):8557–63. doi: 10.1021/ac071311w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyvantsson I, et al. Automated cell culture in high density tubeless microfluidic device arrays. Lab Chip. 2008;8(5):717–24. doi: 10.1039/b715375a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu LY, Di Carlo D, Lee LP. Microfluidic self-assembly of tumor spheroids for anticancer drug discovery. Biomed Microdevices. 2008;10(2):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wlodkowic D, et al. Microfluidic single-cell array cytometry for the analysis of tumor apoptosis. Anal Chem. 2009;81(13):5517–23. doi: 10.1021/ac9008463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaneko T, Kojima K, Yasuda K. An on-chip cardiomyocyte cell network assay for stable drug screening regarding community effect of cell network size. Analyst. 2007;132:892–898. doi: 10.1039/b704961g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu T, et al. Microfluidic formation of single cell array for parallel analysis of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel activation and inhibition. Anal Biochem. 2010;396(2):173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tan WH, Takeuchi S. Dynamic microarray system with gentle retrieval mechanism for cell-encapsulating hydrogel beads. Lab Chip. 2008;8(2):259–66. doi: 10.1039/b714573j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ringeisen BR, Spargo BJ, Wu PK. Cell and Organ Printing. Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guillemot F, et al. High-throughput laser printing of cells and biomaterials for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu T, et al. High-throughput production of single-cell microparticles using an inkjet printing technology. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Transactions of the ASME. 2008;130(2):0210171–0210175. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu F, et al. A three-dimensional in vitro ovarian cancer coculture model using a high-throughput cell patterning platform. Biotechnology Journal. 2011;6(2):204–212. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khalil S, Sun W. Bioprinting endothelial cells with alginate for 3D tissue constructs. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(11):111002. doi: 10.1115/1.3128729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moon S, et al. Layer by layer three-dimensional tissue epitaxy by cell-laden hydrogel droplets. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16(1):157–66. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mironov V, et al. Organ printing: Tissue spheroids as building blocks. Biomaterials. 2009;30(12):2164–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boland T, et al. Application of inkjet printing to tissue engineering. Biotechnol J. 2006;1(9):910–7. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ringeisen BR, et al. Jet-based methods to print living cells. Biotechnol J. 2006;1(9):930–48. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pirlo RK, et al. Cell deposition system based on laser guidance. Biotechnol. J. 2006;1:1007–1013. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jayasinghe SN, Eagles PAM, Qureshi AN. Electrohydrodynamic jet processing: an advanced electric-field-driven jetting phenomenon for processing living cells. Small. 2006;2:216–219. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hart T, et al. Human cell chips: adapting DNA microarray spotting technology to cell-based imaging assays. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee MY, et al. Three-dimensional cellular microarray for high-throughput toxicology assays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(1):59–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708756105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Song YS, et al. Vitrification and levitation of a liquid droplet on liquid nitrogen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(10):4596–4600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Demirci U, Toner M. Direct etch method for microfludic channel and nanoheight post-fabrication by picoliter droplets. Applied Physics Letters. 2006;88(5) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Demirci U, Montesano G. Single cell epitaxy by acoustic picolitre droplets. Lab Chip. 2007;7(9):1139–45. doi: 10.1039/b704965j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Elrod A, et al. Nozzleless droplet formation with focused acoustic beams. J. Appl,. Phys. 1989;65:3441. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Demirci U, Montesano G. Cell encapsulating droplet vitrification. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7(11):1428–1433. doi: 10.1039/b705809h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Demirci U. Droplet-based photoresist deposition. Applied Physics Letters. 2006;88:13. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Demirci U, Ozcan A. Picolitre acoustic droplet ejection by femtosecond laser micromachined multiple-orifice membrane-based 2D ejector arrays. Electronics Letters. 2005;41(22):1219–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Demirci U, et al. Femtoliter to picoliter droplet generation for organic polymer deposition using single reservoir ejector arrays. Ieee Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing. 2005;18(4):709–715. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Demirci U, et al. Acoustically actuated flextensional SixNy and single-crystal silicon 2-D micromachined ejector arrays. Ieee Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing. 2004;17(4):517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Demirci U. Acoustic Picoliter Droplets for Emerging Applications in Semiconductor Industry and Biotechnology. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems. 2006;15(4):957–966. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu F, et al. A droplet-based building block approach for bladder smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation. Biofabrication. 2010;2(1):014105. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/1/014105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moon S, et al. Drop-on-Demand Single Cell Isolation and Total RNA Analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Samot J, et al. Blood banking in living droplets. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu F, et al. Multi-scale heat and mass transfer modelling of cell and tissue cryopreservation. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;368(1912):561–83. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tasoglu S, et al. Impact of a compound droplet on a flat surface: A model for single cell epitaxy. Phys Fluids. 2010;22(8) doi: 10.1063/1.3475527. 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu F, et al. Cell Bioprinting as a Potential High-Throughput Method for Fabricating Cell-Based Biosensors (CBBs). Ieee Sensors. 2009;1-3:368–372. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xu F, et al. Carapezza EM, editor. A high-throughput label-free cell-based biosensor (CBB) system. Unattended Ground, Sea, and Air Sensor Technologies and Applications Xii. 2010.

- 102.Geckil H, et al. Engineering hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics. NanoMedicine. 2010;5(3):469–484. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Song YS, et al. Engineered 3D tissue models for cell-laden microfluidic channels. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;395(1):185–93. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2935-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Park JH, et al. Microporous Cell-Laden Hydrogels for Engineered Tissue Constructs. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2010;106(1):138–148. doi: 10.1002/bit.22667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fernandes TG, et al. On-chip, cell-based microarray immunofluorescence assay for high-throughput analysis of target proteins. Anal Chem. 2008;80(17):6633–9. doi: 10.1021/ac800848j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bailey SN, Sabatini DM, Stockwell BR. Microarrays of small molecules embedded in biodegradable polymers for use in mammalian cell-based screens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(46):16144–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404425101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee MY, et al. Metabolizing enzyme toxicology assay chip (MetaChip) for high-throughput microscale toxicity analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(4):983–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406755102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Upadhyaya S, Selvaganapathy PR. Microfluidic devices for cell based high throughput screening. Lab Chip. 10(3):341–8. doi: 10.1039/b918291h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gosalia DN, Diamond SL. Printing chemical libraries on microarrays for fluid phase nanoliter reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(15):8721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530261100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ma H, et al. Nanoliter homogenous ultra-high throughput screening microarray for lead discoveries and IC50 profiling. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3(2):177–87. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Paul JH, et al. Continuous perfusion microfluidic cell culture array for high- throughput cell-based assays. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2005;89(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/bit.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.MacBeath G, Schreiber SL. Printing proteins as microarrays for high-throughput function determination. Science. 2000;289(5485):1760–3. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhu H, et al. Analysis of yeast protein kinases using protein chips. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):283–9. doi: 10.1038/81576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Psaltis D, Quake SR, Yang C. Developing optofluidic technology through the fusion of microfluidics and optics. Nature. 2006;442(7101):381–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yager P, et al. Microfluidic diagnostic technologies for global public health. Nature. 2006;442(7101):412–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee YB, et al. Bio-printing of collagen and VEGF-releasing fibrin gel scaffolds for neural stem cell culture. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(2):645–52. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Duocastella M, et al. Printing biological solutions through laser-induced forward transfer. Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing. 2008;93(4):941–945. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Phillippi JA, et al. Microenvironments engineered by inkjet bioprinting spatially direct adult stem cells toward muscle- and bone-like subpopulations. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):127–34. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Friedrich J, Ebner R, Kunz-Schughart LA. Experimental anti-tumor therapy in 3-D: spheroids--old hat or new challenge? Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83(11-12):849–71. doi: 10.1080/09553000701727531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):241–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kozak K, et al. Data mining techniques in high content screening: a survey. Journal of Computer Science & Systems Biology. 2009;2 doi:10.4172/jcsb.1000035. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pardo-Martin C, et al. High-throughput in vivo vertebrate screening. Nat Methods. 2010;7(8):634–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schonbrun E, et al. High-throughput fluorescence detection using an integrated zone-plate array. Lab on a Chip. 2010;10(7):852–856. doi: 10.1039/b923554j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Xu F, Demirci U. Automated and adaptable quantification of cellular alignment from microscopic images for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0038. DOI: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2011.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fukuda J, et al. Micromolding of photocrosslinkable chitosan hydrogel for spheroid microarray and co-cultures. Biomaterials. 2006;27(30):5259–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tsang VL, et al. Three-dimensional tissue fabrication. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2004;56(11):1635–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Liu VA, Bhatia SN. Three-Dimensional Photopatterning of Hydrogels Containing Living Cells. Biomedical Microdevices. 2002;4(4):257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Demirci U. Picoliter droplets for spinless photoresist deposition. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2005;76:065103. [Google Scholar]