Abstract

Implanted silicone medical prostheses induce a dynamic sequence of histologic events in adjacent tissue resulting in the formation of a fibrotic peri-prosthetic capsule. In some cases, capsular calcification occurs, requiring surgical intervention. In this study we investigated capsules from silicone gel-filled breast prostheses to test the hypothesis that this calcification might be regulated by the small vitamin K-dependent protein, matrix Gla protein (MGP), a potent inhibitor of arterial calcification, or by Fetuin-A, a hepatocyte-derived glycoprotein also implicated as a regulator of pathologic calcification. Immunolocalization studies of explanted capsular tissue, using conformation-specific antibodies, identified the mineralization-protective γ-carboxylated MGP isomer (cMGP) within cells of uncalcified capsules, whereas the non-functional undercarboxylated isomer (uMGP) was typically absent. Both were upregulated in calcific capsules and co-localized with mineral plaque and adjacent fibers. Synovial-like metaplasia was present in one uncalcified capsule in which MGP species were differentially localized within the pseudosynovium. Fetuin-A was localized to cells within uncalcified capsules and to mineral deposits within calcific capsules. The osteoinductive cytokine bone morphogenic protein-2 localized to collagen fibers in uncalcified capsules. These findings demonstrate that MGP, in its vitamin K-activated conformer, may represent a pharmacological target to sustain the health of the peri-prosthetic tissue which encapsulates silicone breast implants as well as other implanted silicone medical devices.

1. Introduction

Implantable medical prostheses made of silicone are used in reconstructive and aesthetic surgery. However clinical complications, including deposition of apatite mineral, are common. For example, the surface of silicone rhinoplastic implants, as well as the peri-prosthetic tissue, may become calcific [1], and silicone intraocular lenses become opaque due to calcific deposits on the lens surface [2]. The most frequently employed silicone prostheses are breast implants. More than 200,000 surgical procedures to insert silicone gel-filled implants for breast reconstruction and augmentation are performed yearly in the United States [3]. Once inserted, a capsule comprising numerous cell types associated with inflammation and wound-healing develops around the implant as a normal response to a foreign body [4]. Over time, the capsule is remodeled, losing cellularity and becoming fibrous. In some patients heterotopic calcification develops, characterized by deposits of bone-like calcium phosphate apatite in association with collagen fibers [5] and also thick plaques on the capsular-implant interface [6–8]. The mineral may cause the breast to become firm, tender, and painful [9, 10], necessitating explantation. The deposits could potentially interfere with clinical evaluation [8] by obscuring mineral that is associated with carcinoma, or by mimicking malignancy on mammography [11]. In addition, severe calcification could induce implant rupture [10]. Although the sequence of events leading to capsular mineralization has been described [6, 7, 12], studies which identify specific underlying mechanisms or protein mediators are lacking.

Because the extracellular milieu of soft tissues often manifests a high Ca × P product and alkaline pH, heterotopic mineralization could occur spontaneously were it not actively inhibited [13]. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and fibroblasts secrete matrix Gla protein (MGP) [14–16], a 14 kDa protein which is insoluble in physiological solutions. MGP can undergo post-translational processing to convert 5 critical glutamate (Glu) residues to glutamic acid (Gla) via a vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. The resulting matrix γ-carboxyglutamic acid protein (cMGP) binds calcium ions and apatite crystals with high affinity [17]. However the immediate post-translational product, undercarboxylated MGP (uMGP), is believed to be non-functional for maintaining calcium homeostasis due to the low affinity of its Glu sites for calcium [18, 19].

Substantial evidence indicates that cMGP is a potent inhibitor of arterial calcification. In healthy arteries, MGP exists almost entirely in the carboxylated form [14]. Mice deficient in MGP die within 6–8 weeks after birth due to rupture of calcified large arteries [13]. In rats, expression of the uMGP isomer increases with aging, concurrent with aortic calcification [19]. Keutel’s syndrome results from mutation of the human MGP gene, in which the resulting production of non-functional MGP leads to abnormal cartilage calcification and stenosis of pulmonary arteries [20]. Furthermore, in patients with the genetic disorder pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), which is characterized by mineralization of elastic fibers, ratios of cMGP/uMGP are abnormally low within calcific dermal elastic fibers, compared to fibers from normal controls, even though MGP mRNA expression levels are similar [15]. Administration of the carboxylase inhibitor warfarin to rats results in vascular accumulation of the immature uMGP conformer and concurrent arterial calcification, processes which can be reversed by vitamin K administration [21]. Removal of calcium complexed with cMGP from the extracellular space inhibits calcification in soft tissues. The cMGP also inhibits inappropriate differentiation of VSMCs and fibroblasts into osteogenic and chondrogenic phenotypes by binding to vascular bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), particularly BMP-2 and BMP-4, through its Gla-containing epitope [19, 22, 23].

MGP is functionally related to human α2-Herermans-Schmid glycoprotein, also known as Fetuin-A, a circulating mineralization inhibitor produced by adult hepatocytes and taken up by osteoblasts and VSMCs. Fetuin-A supports physiological homeostasis by inhibiting spontaneous extracellular apatite precipitation, by blocking the growth of small apatite crystals, by removing excess intracellular calcium via vesicle release, and by inhibiting apoptosis [24, 25].

The current study was designed to examine whether capsular mineralization is associated with MGP carboxylation state. We hypothesized that breast capsules which were uncalcified and largely cellular would express the calcification-protective cMGP conformer but not uMGP, whereas capsules which had become fibrotic, with deposits of apatite mineral, would express a greater level or proportion of uMGP. Studies were performed to compare the expression and localization of isomeric MGP species and also the mineralization-modulating proteins Fetuin-A, BMP-2, and BMP-4 in explanted calcified and uncalcified capsules. The capacity of extracts from calcified versus uncalcified breast capsules to promote mineralization in vitro was also assessed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peri-implant capsular tissue

All surgical procedures were performed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Surgical waste tissue was obtained as approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB #PR07-002791). Capsular specimens were placed in sterile saline and transported immediately to the laboratory. The thickness of each capsule and of surface calcific plaque, if present, was measured at 6 different sites and averaged. Specimens were rinsed in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and two 5 × 20 mm pieces were cut from each; one for in vitro experiments to determine the calcification potential of the fresh capsule, and one for histological investigation. From some capsules a third, 5 × 5 mm piece was cut for examination by scanning-electron microscopy (SEM).

2.2. Determination of calcification potential

Capsular specimens were grouped after visual inspection for the presence or absence of deposited mineral. Each 5 × 20 mm specimen was placed in 0.2 ml ice-cold PBS, minced, homogenized, filtered (0.2 µm), inoculated into 5 ml DMEM cell culture medium containing 10% γ-irradiated fetal bovine serum, and maintained under cell culture conditions [26]. After 2 weeks, a film comprised of calcifying nanoparticles (NPs) – nano-sized complexes of calcium phosphate and proteins [26, 27] - which had developed during culture and adhered to the bottom of each flask during incubation was then scraped into the medium, and pooled with the free-floating, or “planktonic” NPs to yield total NPs. The total NPs were then quantified in nephelometric turbidity units (NTU) using a turbidimeter (Model 2100N; Hach Co., Loveland, CO). This value was used as an index of the calcification potential, i.e., the capacity to induce calcification, of the original explanted capsule [26]. Culture medium treated identically except for the omission of capsular isolate was used as a control.

2.3. Scanning electron microscopy

Duplicate sections of fresh capsular tissue cut for SEM were placed in Trump’s fixative overnight at 4°C and then stained with osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and critical-point dried using CO2. One specimen was mounted on an aluminum stub and sputter-coated with gold-palladium for SEM imaging (Hitachi 4700 scanning-electron microscope; Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc., Schaumburg, IL). The duplicate specimen was carbon-coated for SEM with energy-dispersive elemental analysis (EDX) using a Noran X-ray Microanalysis system (Noran Instruments, Middleton, WI). In order to verify the mineral composition of cultured NPs after harvesting, they were centrifuged at 20,000 X g, and the pelleted NPs were then resuspended in Trump’s fixative, placed on a carbon stub, rinsed in water, and analyzed by EDX.

2.4. Histological investigations

Freshly isolated pieces of capsule were pinned lengthwise to a Teflon stick and fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% formalin, pH 7.0. These specimens were then paraffin-embedded, and 5 µm-thick serial cross-sections cut and placed on slides. Slides were then deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin, eosin and silver nitrate (von Kossa) to examine histological structures, nuclei, and mineralization deposits, respectively, by light microscopy. Subsequent serial sections were used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) studies. PBS was used as a buffer throughout the staining procedures, and each rinsing step utilized three changes of buffer.

2.4.1. Immunohistochemistry

Prior to staining, three serial sections from each capsule specimen were placed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min to retrieve antigens. The sections were rinsed, then permeabilized with 0.05% Tween-20 for 5 min, and non-specific antibody binding was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (0.45 µm filtered) for 60 min. Immunostaining was then performed at 25°C using one of three mouse monoclonal antibodies (moAb) per slide, each of which recognizes a different human MGP epitope (Table). Antibody moAb pMGP is directed against residues 3–15 of phosphorylated MGP (pMGP), which are outside of the Gla domain and which contain 3 pSer. For this study, the MGP recognized by this antibody was considered to represent total MGP, both undercarboxylated and γ-carboxylated, since the phospho-MGP protein has been shown to predominate in soft tissues [28]. Each of the remaining 2 specimens was probed with a conformation-specific MGP antibody; either moAb uMGP or moAb cMGP, which recognize residues within the MGP Glu- and Gla-domains, respectively. Each antibody was applied for 120 min, then slides were rinsed in blocking buffer, followed by secondary antibody labeling with biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (Vectastain ABC-AP Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 90 min. Each slide was then incubated with avidin-linked alkaline phosphatase complex (Vector Labs) for 30 min, and stained using a Vector Red alkaline phosphatase substrate kit I (Vector) for 30 min. Levamisole (0.5 mM) was added to the substrate buffer to inhibit endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity, if present. Specimens were counterstained with hematoxylin, cleared to xylene and cover-slipped. They were then examined using light microscopy (Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a Plan-Neofluar 20X/0.50 na lens; Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

Primary antibodies

| Human antigen | Ab type | Directed against amino acids |

Dilution | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IHCa | IFb | ||||

| Phospho-MGP (pMGP) | Mouse moAb-IgG1 | 3–15 | 5 µg/ml | 1:250 | c |

| descarboxy-MGP(uMGP) | Mouse moAb-IgG1 | 35–49 | 1 µg/ml | 1:250 | c |

| γ-carboxy-MGP (cMGP) | Mouse moAb-IgG1 | 35–54 | 1 µg/ml | 1:250 | c |

| Fetuin-A | Rabbit poAb-IgG | 68–367 | - | 1:200 | d |

| BMP-2/4 | Rabbit poAb-IgG | 300–350 (BMP-4) | - | 1:150 | d |

Secondary Ab: biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG/ALP substrate Kit I (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Secondary Abs for MGP isoforms: Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:200; for all others: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR

VitaK BV, Maastricht, Netherlands.

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA.

-, Not examined by IHC

2.4.2. Immunofluorescence

Each capsule section was probed for one of the three MGP species described above, and simultaneously for either Fetuin-A or BMP-2/4 (Table). Primary antibodies were applied and slides rinsed as described for IHC. Anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody fluorescent conjugates, Alexa Fluor® 488 and Alexa Fluor® 568, respectively, were then applied for 60 min. Next, slides were rinsed, and cover-slips were applied using ProLong® Gold anti-fade reagent containing DAPI, a nuclear stain excitable at 341 nm. Capsular sections processed identically, with primary antibodies omitted, served as imaging controls. Specimens were imaged by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM) using a Model LSM 510 confocal laser-scanning microscope, equipped with a C-Apochromat 40X/1.2 na water lens; Zeiss, Inc.) and also using a dark-field/fluorescence light microscope (Olympus BX41 with a 100X oil-immersion lens) coupled to a CytoViva illumination system (CytoViva, Inc., Auburn, AL).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least 5 determinations each. Differences were determined using the Student’s t-test and were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient data

Twelve peri-implant capsules from 8 patients were examined; average patient age 60.1 ± 2.5 yrs, and implant time in situ, 24.2 ± 2.3 yrs. Capsulectomies were prompted by capsular contracture, calcification, prosthesis rupture, or for resizing. Implants were silicone gel-filled and most were third-generation. One, fifth-generation implant was removed after 2 years in situ due to cancer.

3.2. Gross/histologic capsular structure

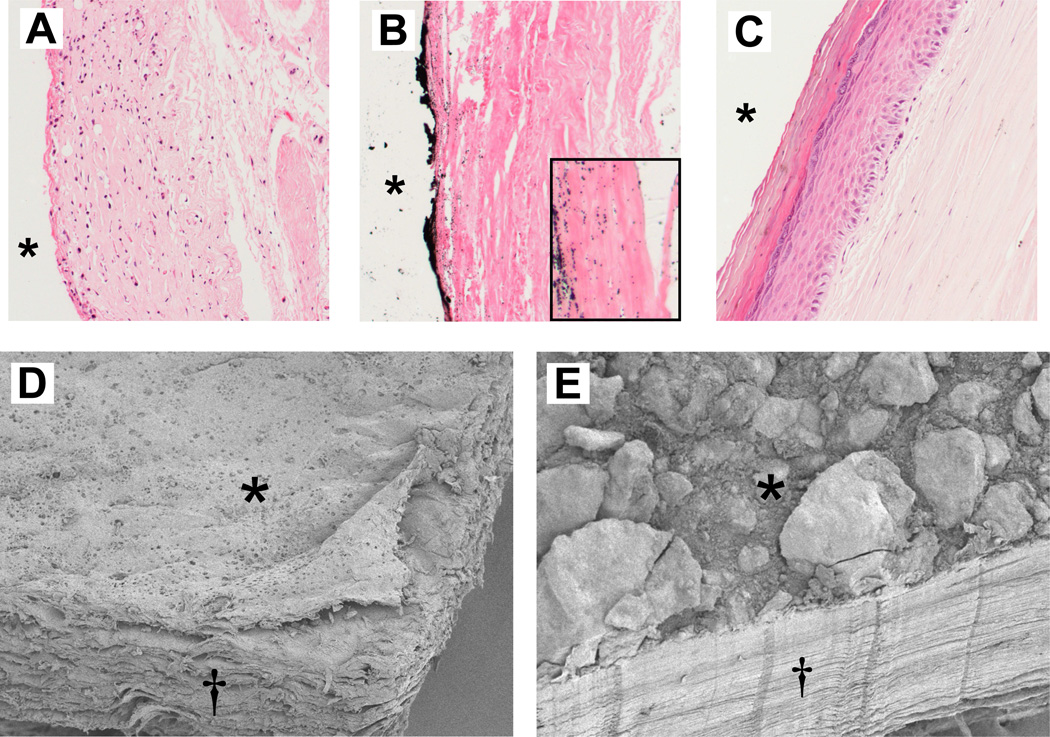

By visual examination, seven of the 12 freshly explanted specimens were pliant, with no observable mineral deposits. Six of these seven were histologically similar, with an interface layer adjacent to the implant composed primarily of fibroblasts and macrophages, a second, deeper layer of loosely-arranged collagen fibers arranged parallel to the capsule interface, and an outer adventitia-like layer comprised of loose connective tissue (Fig. 1A). Von Kossa staining of these six specimens was negative for calcium deposits, and SEM demonstrated that the capsule interface was smooth (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the remaining pliant capsule exhibited synovial-like metaplasia (Fig. 1C). This capsule had a thin fibrous interface layer below which was a layer of pseudo-epithelium comprised of a layer of squamous cells, some of which were anucleate, covered by a basal layer of cuboidal cells. Further beneath this layer was a thicker region of loosely-arranged fibers interspersed with small arterioles.

Fig. 1.

Fine structure of explanted breast capsular tissue. Light microscopy of thin-sections (top) stained with H&E (nuclei blue, cells red) and von Kossa (mineral, black). Typical uncalcified capsule (A) with a hypercellular interface layer, a deeper layer of cells/collagen fibers, and a third, adventitial-like layer. Calcific capsule (B) is sparsely populated with cells; von Kossa labeled a mineral plaque on the interface surface, and small deposits associated with adjacent collagen fibers (inset). Synovial-like metaplasia was present in one capsule (C). *, implant position before capsulectomy. SEM of section of uncalcified capsule (D) shows smooth interface surface (*) and loosely-arranged fibers, seen in cross-section (†). Comparable section of calcific capsule, with large surface mineral agglomerates, and dense, uniformly-arranged collagen fibers (E).

The five non-pliant capsules were firm, with a plaque comprised of mineral agglomerates up to 4 mm thick located at the interface with the implant (Figs. 1B, 1E). These capsules contained several layers of uniformly arranged collagen fibers sparsely populated with cells, mostly fibroblasts, with an interface layer of densely-packed fibers adjacent to the prosthesis (Fig1B). Von Kossa identified calcium within the plaque as well as in microcalcifications in the associated fibrous layer. Calcified and uncalcified capsules averaged 1.6 ± 0.4 and 1.1 ± 0.1 mm in thickness, respectively.

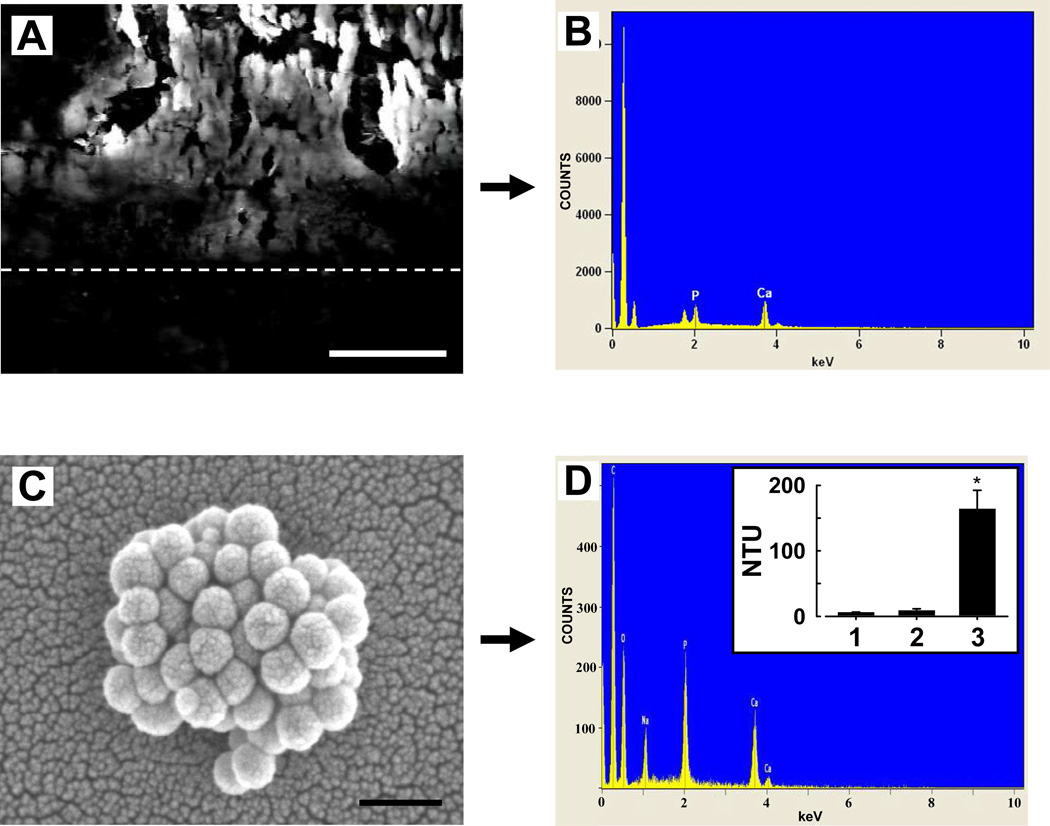

3.3. Capsular calcification potential

The capsular mineral deposits were comprised of calcium phosphate, as determined by SEM-EDX (Figs. 2A, 2B). After processing for in vitro calcification assay, spherical nano-sized structures containing calcium and phosphate, i.e., calcifying NPs, developed in each culture medium inoculated with an isolate from a calcified capsule (Figs. 2C, 2D). The calcification potential of these five capsules, by total NTU, was 164 ± 28.3 NTU (Fig. 2D, inset). In contrast, NPs did not develop in cultures inoculated with isolates of pliant capsules. The calcification potential of these uncalcified capsules was 8.9 ± 2.4 NTU (n= 7), not significantly different from flasks inoculated with vehicle alone (6.1 ± 0.5 NTU; n=10).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of a calcified capsule and calcification potential of silicone breast implant capsular tissue, determined in vitro. A, cross-section of an explanted calcified capsule imaged by SEM. Dotted line indicates approximate capsule interface, with mineral crystals on the surface above. EDX of mineral reveals Ca and P peaks (B). When 0.2 µm-filtered isolates of each fresh tissue were placed in culture conditions, calcifying NPs developed in the medium within 2 weeks from 5 of 12 capsules examined, demonstrating positive calcification potential. C, SEM micrograph of NPs formed in vitro; these were comprised of Ca and P (D). Inset in D: 5 specimens yielded a high calcification potential (3), determined by measurements of medium turbidity after culture; homogenate from the remaining 7 capsules (2) did not induce mineralization, since turbidity levels were similar to the culture blanks (1). *, sig, dif. (P < 0.05) from uncalcified sample. Bars: (A), 25 µm; (C), 250 nm.

3.4. Immunolocalization of MGP species

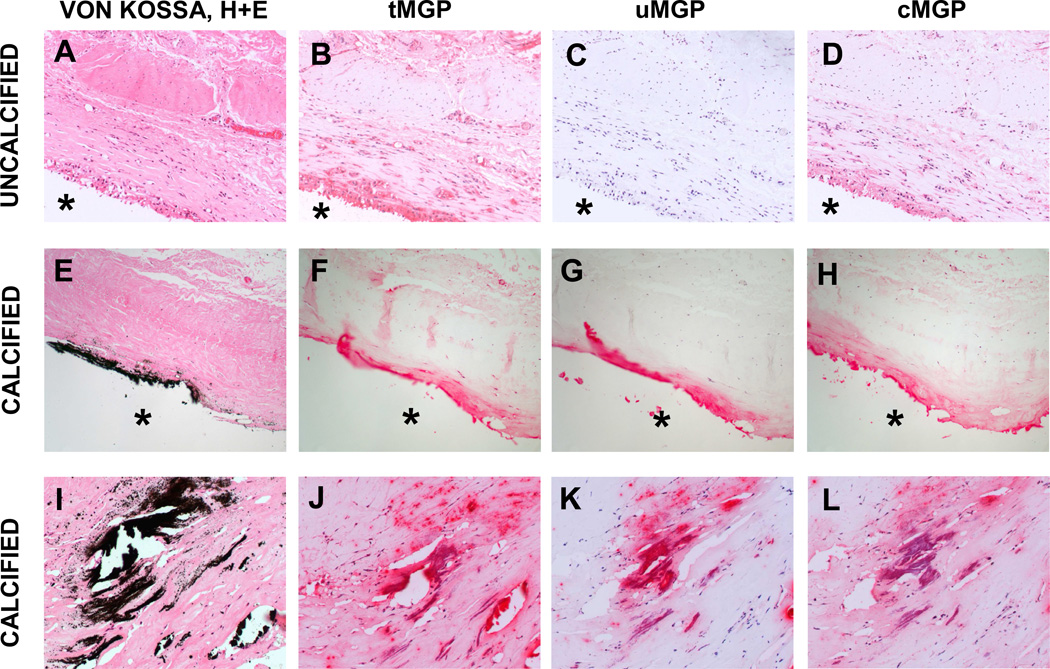

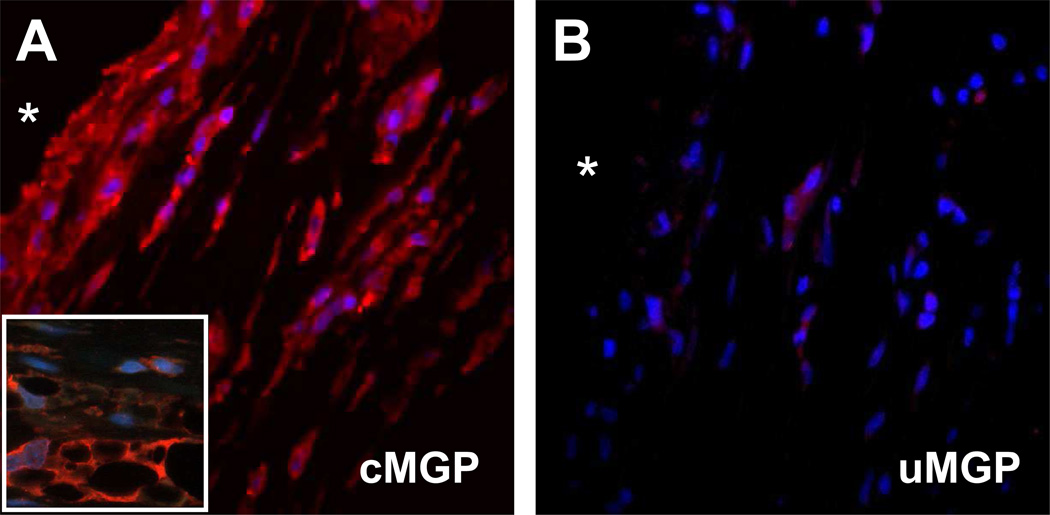

Total MGP (tMGP) was detected in uncalcified capsules by IHC using an antibody which recognizes both carboxylated and undercarboxylated isoforms (Fig. 3B). The most intense staining was within the cellular layer at the capsule interface. Serial sections probed with antibodies specific for uMGP or for cMGP revealed that MGP was present almost entirely as the γ-carboxylated isoform in uncalcified capsules (Figs. 3C, 3D). MGP was also identified within calcified capsules (Fig. 3F). Both isoforms localized to calcified areas of the plaque (identified by von Kossa; Fig. 3E) and the adjacent fibrous layer (Figs. 3G, 3H). Cells within these capsules also stained positively for cMGP, but not for uMGP. Higher magnification images of calcified regions confirmed that both uMGP and cMGP isomers co-localized with mineral, whereas only cMGP was present within cells (Figs. 3I–L). IF studies provided greater detail, and revealed that the interface layer of uncalcified capsules contained spindle-shaped fibroblasts and vacuolous macrophages; both cell types were immunolabeled for cMGP by fluorescence microscopy (Figs. 4A, 4B).

Fig. 3.

Localization of MGP species in representative uncalcified (top) and calcified (middle, bottom) breast capsules by IHC. Black von Kossa staining was negative in the uncalcified capsule, which stained for cells by H&E (A). Total MGP was widely distributed (B), primarily as the carboxylated isomer (C, D). The calcific capsule displayed deposited mineral (E). MGP was also present (F); uMGP was localized with or near the plaque (G) whereas cMGP was associated with the plaque and was also intracellular (H). Higher magnification of a heavily calcified area confirmed that both uMGP and cMGP species were associated with mineral deposits, whereas only the mature cMGP isomer was present intracellularly (J–L). Magnification, 20X; *, implant position before capsulectomy.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular localization of MGP species in an uncalcified breast capsule, determined by IF/light microscopy. Staining of the cellular layer near the capsular interface showed intense labeling for cMGP (A); uMGP labeling was weak (B). Higher magnification in A (inset) shows vacuolous macrophages and fibroblast-like cells. *, implant position before capsulectomy. Base magnification, 100X.

3.5. Expression of Fetuin-A and BMP-2/4

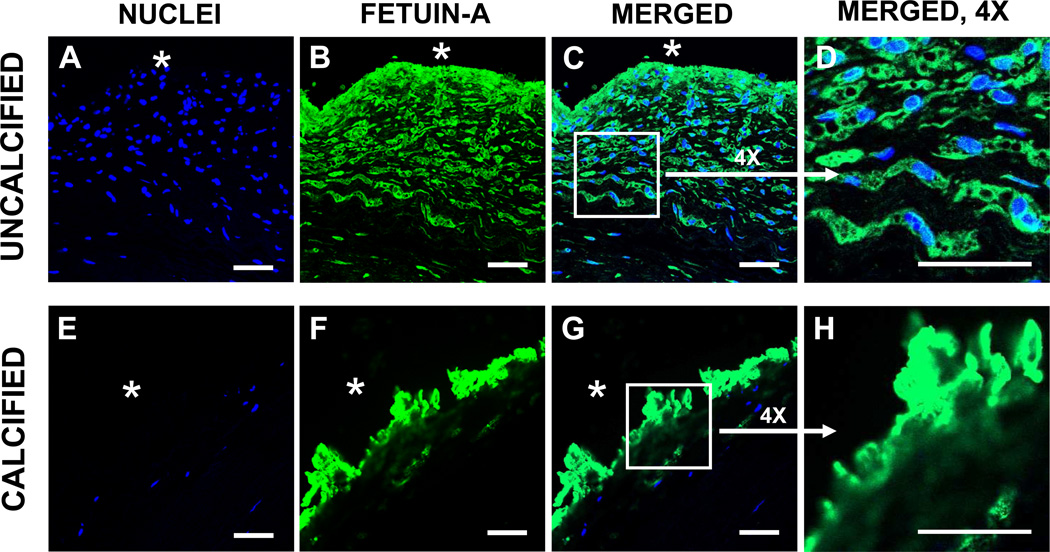

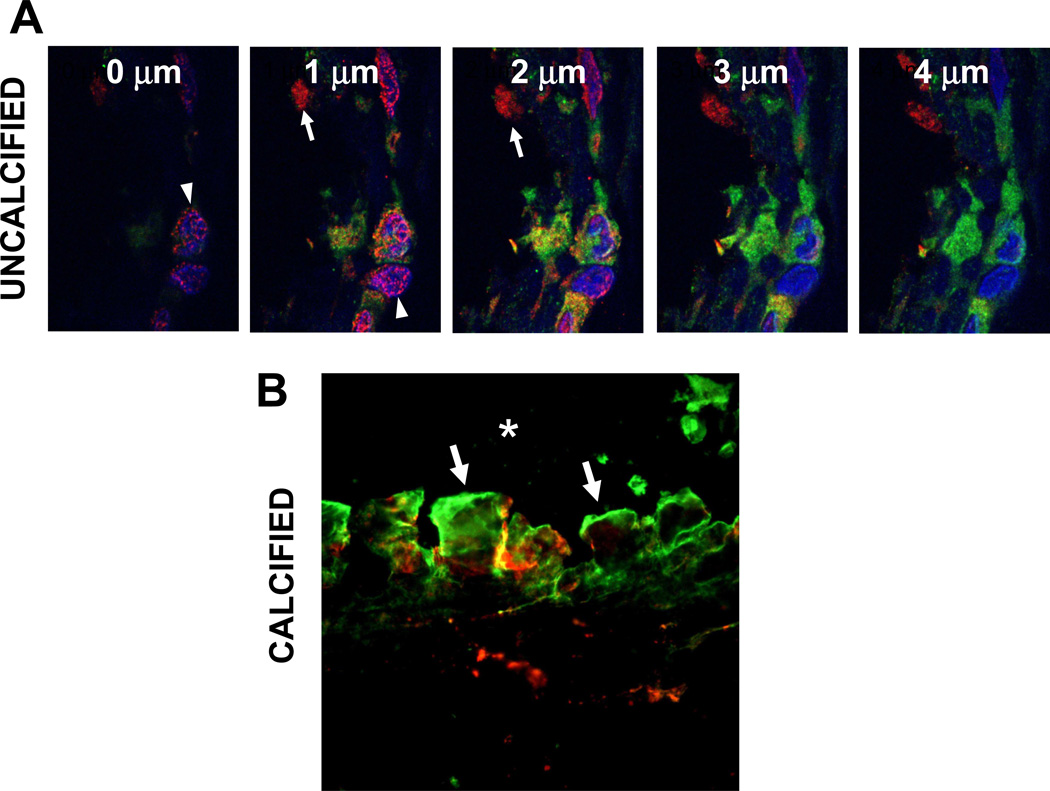

Fetuin-A was also identified intracellularly within uncalcified capsules (Fig. 5A–5D). The punctate and diffuse labeling patterns suggest both vesicular and cytoplasmic distribution. In calcified capsules, neither the fibers nor the sparse cells labeled for Fetuin-A. However, strong positive labeling was localized within the plaque itself (Figs. 5E–5H). Dual-antibody labeling studies using CLSM with optical slicing at 1 µm increments provided sufficient detail to demonstrate that tMGP and Fetuin-A were only minimally co-localized within uncalcified capsules (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, both antigens were localized to the mineral deposits of calcified capsules, although little co-localization was observed (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 5.

Fetuin-A localization in breast capsular tissue determined using IF/CLSM. In a thin-section of an uncalcified capsule (top), Fetuin-A (green) was localized in spindle-shaped fibroblast-like cells and in vacuolated macrophages. The sparsely cellular calcified capsule (bottom) displayed Fetuin-A labeling associated with the mineral plaque at the capsular interface with the silicone implant. Nuclei identified by DAPI labeling (blue). *, implant position before capsulectomy. Bars, 50 µm.

Fig. 6.

Capsular co-localization of tMGP/Fetuin-A. A, CLSM micrographs of a single field of an uncalcified capsule taken in z-step planes of 1 µm increments. MGP antigen (red) is distributed diffusely in cytoplasm in some cells (arrows) and is localized to peri-nuclear punctate structures, likely endoplasmic reticulum (arrowheads) in others. Fetuin-A antigen (green) is cytoplasmic, however little tMGP/Fetuin-A co-localization (yellow) is noted. B, interface of calcific capsule containing large surface mineral agglomerates (arrows); both antigens are associated with mineral, either discretely or are co-localized. Only tMGP was present in underlying fibers. *, implant position.

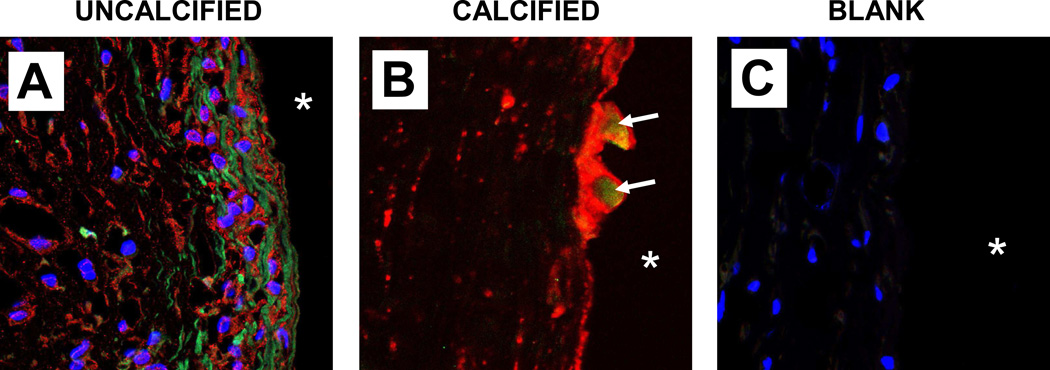

BMP was identified in uncalcified capsules using the poAb BMP-2/4 which recognizes both BMP-2 and BMP-4 (Fig. 7A). Staining for the BMP antigen(s) was restricted to collagen fibers, whereas tMGP was only intracellular; co-localization was not observed in uncalcified capsules. However, in calcified capsules, the two antigens co-localized in discrete regions of surface plaque (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Identification of BMP species in capsular tissue by IF/CLSM. A, positive immunostaining for BMP-2/4 (green) was localized to collagen fibers of uncalcified capsule. Concurrent labeling showed tMGP (red) to be within cells adjacent to the fibers; co-localization was absent. Nuclei showed blue DAPI staining. A comparable section of a calcified capsule treated similarly (B) displayed intense tMGP labeling associated with mineral; BMP-2/4 was present only within the surface plaque (arrows). An uncalcified capsule section treated identically except for omission of primary antibodies in order to verify absence of autofluorescence displayed only labeled nuclei (C).

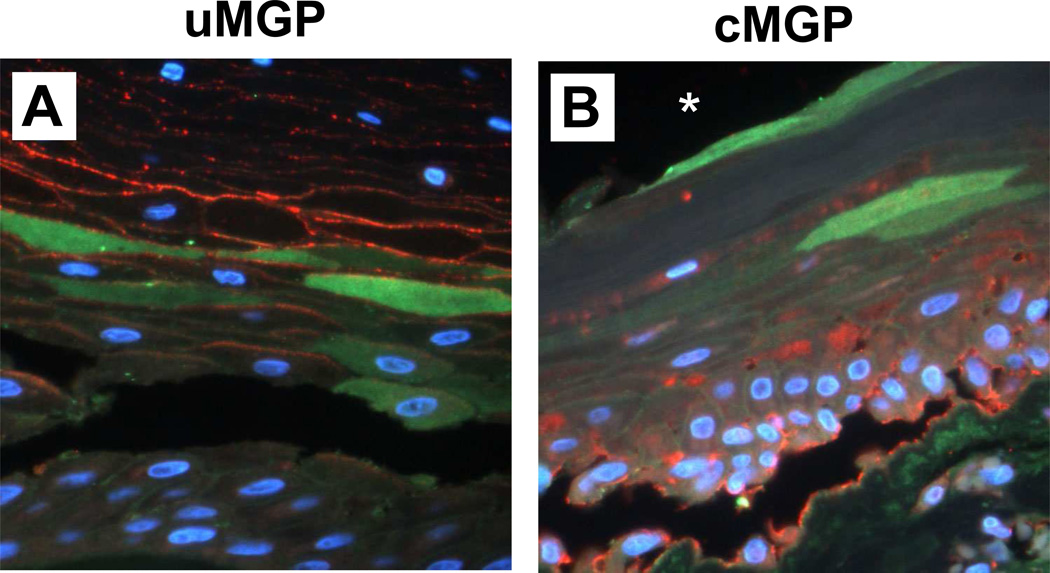

3.6. MGP and Fetuin-A expression in synovial-like metaplasia

Undercarboxylated MGP was associated with the layer of collagen fibers adjacent to the implant, and within squamous cells of a pseudo-epithelial layer near the capsule-implant interface (see Fig. 1C, Fig. 8A). In contrast, cMGP was present primarily within and on the surface of basal cuboidal cells, and also within fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 8B). Fetuin-A immunolocalization was displayed within some of the squamous cells; co-localization with MGP species was absent.

Fig. 8.

Synovial-like metaplasia in a peri-prosthetic breast capsule. IF/light micrographs of capsule thin-sections dual-labeled for MGP species (red) and Fetuin-A (green). A thin layer of collagen fibers abutted the implant (not shown); a deeper layer of stratified epithelium comprised squamous cells, some of which were anucleate, and a basal layer of cuboidal cells. A, the uMGP antigen was restricted to squamous cell membranes, whereas Fetuin-A was localized cytoplasmically within a sub-layer of squamous cells. In contrast, cMGP labeling was primarily within basal cuboidal cells of the lower epithelial layer (B). Antigen co-localization was absent. Nuclei show blue DAPI label. *, implant position before capsulectomy in B; the field in A is slightly deeper relative to implant.

4. Discussion

These findings demonstrate that MGP and Fetuin-A are expressed within the capsule which develops around silicone breast implants, and suggest that vitamin K-dependent post-translational modification of MGP confers resistance to capsular calcification. Uncalcified capsules revealed abundant intracellular staining for cMGP, the mineralization-inhibitory MGP isomer, whereas both cMGP and uMGP were upregulated and present at similar levels within calcified capsules. These observations suggesting a role for cMGP in preventing pathologic calcification are similar to those in healthy human vascular tissues [14], and dermis [15], and underscore the requirement for γ-carboxylation of MGP in order to initiate its calcification-protective properties. Extracellular fluids often have a high Ca × P product, which in turn favors spontaneous mineral precipitation. Therefore, local calcification inhibitors have an essential role in maintaining healthy soft tissues [13]. Gamma-carboxylated MGP may serve this function in “healthy”, i.e., uncalcified breast capsules, partly by binding free calcium as well as small calcium phosphate crystals at nascent foci of pathologic mineralization, facilitating their clearance to the circulation [17, 29]. The high proportion of cMGP to uMGP present within uncalcified capsules indicates that γ-carboxylase activity was present at levels sufficient to convert immature, uMGP to its functional conformer. Adequate vitamin K reserves must also have been present locally within the capsular tissues, since this process requires the reduced form of vitamin K (vitamin KH2) as a cofactor [21, 30]. Punctate, perinuclear staining for MGP was observed within cells of the uncalcified capsules, probably indicating the endoplasmic reticulum, the site of glutamate carboxylation [30].

Deeper layers within calcified capsules reveal a transition to a fibrous, hypocellular composition with sparse labeling for MGP species. The high levels of both uMGP and cMGP observed within the large calcific plaques and within small mineral deposits associated with collagen fibers were likely induced in response to local mineral precipitation [19, 21]. A calcium-sensing receptor-like pathway which can regulate MGP synthesis has been noted in vascular smooth muscle cells [31] and, if present in capsular tissue, could initiate robust upregulation of MGP. However, when pathologically high Ca × P product levels are present, increased local synthesis of MGP might not reach sufficient levels, resulting in mineral deposition. Once calcification is initiated, MGP would be incorporated into the resulting crystals and extracellular matrix, as noted in this study.

The present findings also suggest a role for Fetuin-A in maintaining peri-implant tissues in the uncalcified state. The mineralization-inhibiting capacity of Fetuin-A in other soft tissues derives from several processes. Fetuin-A binds to extracellular calcium and phosphate, present at supersaturated levels, forming a stable complex which prevents spontaneous hydroxyapatite crystal growth [32]. In certain cells, such as osteoblasts and VSMCs, Fetuin-A is internalized via a calcium- and annexin II-dependent mechanism [33], and loaded into matrix vesicles where it binds calcium. The vesicles are subsequently released, which prevents intracellular calcium overload [25]. Our finding that Fetuin-A and tMGP co-localize in a punctate labeling pattern in some cells of non-calcified capsules might represent these vesicles grouped in sufficient numbers to become identifiable by CLSM. Fetuin-A also protects against potential cell death due to increased levels of extracellular calcium, thus inhibiting apoptosis, and also by augmenting adhesion of apoptotic bodies to adjacent cells for phagocytosis [25]. Additionally, Fetuin-A inhibits osteogenic activity in vitro by binding BMP-2 and BMP-4 [34]. Our observation that Fetuin-A co-localizes with calcific deposits in breast capsular tissue is similar to results obtained by others in human arteries [25, 35] and calcific wrist lesions [36]. This association appears counterintuitive, given the anti-mineralization properties of Fetuin-A. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed by Reynolds et al [25] and Moe et al [35]. A primary factor appears to be that increases in extracellular Ca × P product may overwhelm the capacity of Fetuin-A-driven processes to maintain local homeostasis. Fetuin-A retains its affinity for calcium under these conditions and the Fetuin-A/calcium complex is incorporated within the accumulating extracellular matrix.

A role for osteoinductive cytokines in capsular tissues is not established. BMP-2 and BMP-4 have similar functions in heterotopic calcification, and in the vasculature, their presence prompts the expression of an osteogenic gene-expression profile [37]. Mature MGP complexes with both BMPs and inhibits their osteoinductive capacity [18, 22, 23, 38]. In this study, we identified prominent BMP-2/4 labeling associated with collagen fibers; however there was no co-localization with MGP, which was intracellular. The tMGP antibody used in this set of experiments recognizes an epitope outside of the Gla domain, thus apparent absence of an MGP/BMP complex could not have been due to camouflaging of cMGP binding sites by bound BMP [19]. It is possible that one or more related BMP antagonists, the polypeptides noggin or chordin, for example, were present and were bound to BMP, preventing its unopposed action. These inhibitors are expressed in the vasculature, and appear to modulate BMP recognition by its cognate receptors [39]. We did identify co-localized tMGP and BMP-2/4 in specific regions of mineral plaque, suggesting in situ complex formation, consistent with previous observations in diseased vasculature [19, 40]. These observations suggest the plaque has a heterogenous composition.

Synovial-like metaplasia is a foreign-body response resulting in the formation of a thin tissue layer characteristic of the synovium which lines normal joints and tendon sheaths. The membranes have been described next to implanted joint [41], tendon [42], voice [43], and testicular devices [44], although most frequently in association with silicone breast prostheses [45]. The function of the tissue is not well understood. However, our finding of differential cellular localization of MGP species in the synovial-like layer suggests a physiologic role, such as capsular remodeling. In peri-prosthetic breast capsules, metaplastic tissue is likely a transitional stage in the dynamic process of capsular maturation, which ultimately leads to fibrosis. MGP is a binding protein for fibronectin (FN) [46, 47], a cell-adhesive matrix glycoprotein secreted by fibroblasts, which is important during growth and development, and for wound healing [48]. Through a complex cell-mediated process, soluble FN is secreted at sites of tissue injury, where local proteases cleave key fragments, resulting in deposition of insoluble matrix components. Dolores et al [49] demonstrated massive FN deposits in peri-prosthetic breast capsular tissue, which were localized adjacent to the implant surface. In the present study we found that the most intense MGP immunoreactivity was associated with this capsular layer, and noted specifically in the capsule with synovial-like metaplasia, the differential localization of the two MGP conformers. Given that MGP and FN co-localize intracellularly, these findings are consistent with the possibility that MGP could exert an effect on capsular histological changes through interactions with FN, and the related glycoprotein vitronectin. Such an interaction remains to be determined, however if confirmed, might contribute to fibrous capsular contracture, a major complicating factor in breast reconstruction and augmentation [45, 50]. Finally, calcification of the capsule, often the ultimate step in its maturation, might be the consequence of MGP-modulated events initiated during the synovial metaplasia stage.

Quantification of NP formation from isolates of breast capsular tissue served as an index of calcification potential. The goal was to examine a possible relationship between MGP and Fetuin-A to the capacity of each capsule to induce mineralization, based on the hypothesis that increased calcification potential might precede actual mineral deposition. This relationship could not be determined directly however, since all capsules with high calcification potential showed positive staining for mineral. The formation of NPs in vitro from isolates of calcified, but not of uncalcified capsules is, however, similar to previous findings in human arteries [26, 27]. In those studies, proteomic evaluation revealed that the mineral is complexed with proteins, including alkaline phosphatase [26], which promotes apatite crystal formation, and Fetuin-A [27], which binds calcium. These findings support the mineral-binding character of MGP and Fetuin-A, and reinforce their potential roles in modulating mineralization in peri-implant tissues.

These immunolocalization studies clearly do not address the functional aspects of the mineralization-modulating proteins identified in maintenance of peri-prosthetic capsular health, including the stimuli which initiate this biologic cascade and ultimate mineralization. However, these observations may form a basis for future studies which employ a mechanistic approach.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated that MGP species, Fetuin-A, and BMP-2/4 are expressed in the peri-prosthetic capsular tissue of silicone breast implants. The mineralization-inhibitory cMGP isomer, localized intracellularly, predominates in healthy uncalcified capsules, whereas peri-prosthetic tissue which has matured into a fibrotic, hypocellular capsule containing mineral deposits expresses both cMGP as well as the non-functional uMGP isomer at elevated levels in association with mineral. Fetuin-A is present intracellularly in uncalcified capsules, partially co-localized with MGP, and is associated with mineral in calcified capsules. Given the mineralization-modulating character of these proteins, our results indicate that their possible role in capsular health be considered during clinical evaluation. MGP in particular, in its vitamin K-activated conformer, may represent a pharmacological target to sustain the health of the peri-prosthetic tissue which encapsulates silicone breast implants as well as other implanted silicone medical devices. Furthermore, the elastomeric shell of the silicone gel-filled implant has the potential at least to serve as a component in a polymer-based drug delivery system which might augment levels of local effectors of capsular mineralization

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a developmental research grant from the Department of Surgery, Mayo Clinic and NIH R21 HL88988. Additionally, the authors thank Jon E. Charlesworth for expert electron microscopy support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jung DH, Kim BR, Choi JY, Rho YS, Park HJ, Han WW. Gross and pathologic analysis of long-term silicone implants inserted into the human body for augmentation rhinoplasty: 221 revision cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1997–2003. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287323.71630.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stringham J, Werner L, Monson B, Theodosis R, Mamalis N. Calcification of different designs of silicone intraocular lenses in eyes with asteroid hyalosis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Report of the 2010 Plastic Surgery Statistics. 2011 Online Available from URL: http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2010-statisticss/Top-Level/2010-US-cosmetic-reconstructive-plastic-surgery-minimally-invasive-statistics2.pdf.

- 4.Anderson JM. Biological responses to materials. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2001;31:81–110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters W, Smith D. Calcification of breast implant capsules: incidence, diagnosis, and contributing factors. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:8–11. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters W, Pritzker K, Smith D, Fornasier V, Holmyard D, Lugowski S, et al. Capsular calcification associated with silicone breast implants: incidence, determinants, and characterization. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:348–360. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199810000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legrand AP, Marinov G, Pavlov S, Guidoin MF, Famery R, Bresson B, et al. Degenerative mineralization in the fibrous capsule of silicone breast implants. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:477–485. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-6989-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raso DS, Greene WB, Kalasinsky VF, Riopel MA, Luke JL, Askin FB, et al. Elemental analysis and clinical implications of calcification deposits associated with silicone breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:117–123. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fodor J, Udvarhelyi N, Gulyas G, Kasler M. Ossifying calcification of breast implant capsule. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1880–1882. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000119879.36610.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumus N. Capsular calcification may be an important factor for the failure of breast implant. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e606–e608. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.11.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herborn CU, Marincek B, Caduff R, Kunzi W, Kubik-Huch RA. Clustered microcalcification following breast implant removal mimicking malignancy. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:807–810. doi: 10.1007/s003300000749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters W, Smith D, Lugowski S, Pritzker K, Holmyard D. Calcification properties of saline-filled breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:356–363. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, Pinero GJ, Loyerm E, Behringer RR, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997;386:78–81. doi: 10.1038/386078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schurgers LJ, Teunissen KJ, Knapen MH, Kwaijtaal M, van Diest R, Appels A, et al. Novel conformation-specific antibodies against matrix gamma-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) protein: undercarboxylated matrix Gla protein as marker for vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1629–1633. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000173313.46222.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gheduzzi D, Boraldi F, Annovi G, DeVincenzi CP, Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C, et al. Matrix Gla protein is involved in elastic fiber calcification in the dermis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum patients. Lab Invest. 2007;87:998–1008. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schurgers LJ, Spronk HM, Skepper JN, Hackeng TM, Shanahan CM, Vermeer C, et al. Post-translational modifications regulate matrix Gla protein function: importance for inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2503–2511. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hackeng TM, Rosing J, Spronk HM, Vermeer C. Total chemical synthesis of human matrix Gla protein. Protein Sci. 2001;10:864–870. doi: 10.1110/ps.44701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallin R, Schurgers L, Wajih N. Effects of the blood coagulation vitamin K as an inhibitor of arterial calcification. Thromb Res. 2008;122:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweatt A, Sane DC, Hutson SM, Wallin R. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 in aortic calcified lesions of aging rats. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:178–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hur DJ, Raymond GV, Kahler SG, Riegert-Johnson DL, Cohen BA, Boyadjiev SA. A novel MGP mutation in a consanguineous family: review of the clinical and molecular characteristics of Keutel syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:36–40. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurgers LJ, Spronk HM, Soute BA, Schiffers PM, DeMey JG, Vermeer C. Regression of warfarin-induced medial elastocalcinosis by high intake of vitamin K in rats. Blood. 2007;109:2823–2831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bostrom K, Tsao D, Shen S, Wang Y, Demer LL. Matrix GLA protein modulates differentiation induced by bone morphogenetic protein-2 in C3H10T1/2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14044–14052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue W, Wallin R, Olmsted-Davis EA, Borras T. Matrix GLA protein function in human trabecular meshwork cells: inhibition of BMP2-induced calcification process. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:997–1007. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleckenstein-Grun G, Thimm F, Czirfuzs A, Matyas S, Frey M. Experimental vasoprotection by calcium antagonists against calcium-mediated arteriosclerotic alterations. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;24 Suppl 2:S75–S84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds JL, Skepper JN, McNair R, Kasama T, Gupta K, Weissberg PL, et al. Multifunctional roles for serum protein fetuin-a in inhibition of human vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2920–2930. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter LW, Shiekh FA, Pisimisis GT, Kim SH, Edeh SN, Miller VM, et al. Key role of alkaline phosphatase in the development of human-derived nanoparticles in vitro. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiekh FA, Charlesworth JA, Sung-Hoon K, Hunter LW, Jayachandran M, Miller VM, et al. Proteomic evaluation of biological nanoparticles isolated from human kidney stones and calcified arteries. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4065–4072. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price PA, Rice JS, Williamson MK. Conserved phosphorylation of serines in the Ser-X-Glu/Ser(P) sequences of the vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein from shark, lamb, rat, cow, and human. Protein Sci. 1994;3:822–830. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price PA, Thomas GR, Pardini AW, Figueira WF, Caputo JM, Williamson MK. Discovery of a high molecular weight complex of calcium, phosphate, fetuin, and matrix gamma-carboxyglutamic acid protein in the serum of etidronate-treated rats. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3926–3934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suttie JW. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:459–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farzaneh-Far A, Proudfoot D, Weissberg PL, Shanahan CM. Matrix gla protein is regulated by a mechanism functionally related to the calcium-sensing receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:736–740. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schafer C, Heiss A, Schwarz A, Westenfeld R, Ketteler M, Floege J, et al. The serum protein alpha 2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A is a systemically acting inhibitor of ectopic calcification. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:357–366. doi: 10.1172/JCI17202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen NX, O'Neill KD, Chen X, Duan D, Wang E, Sturek MS, et al. Fetuin-A uptake in bovine vascular smooth muscle cells is calcium dependent and mediated by annexins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F599–F606. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00303.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binkert C, Demetriou M, Sukhu B, Szweras M, Tenenbaum HC, Dennis JW. Regulation of osteogenesis by fetuin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28514–28520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moe SM, Reslerova M, Ketteler M, O'Neill K, Duan D, Koczman J, et al. Role of calcification inhibitors in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease (CKD) Kidney Int. 2005;67:2295–2304. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazama JJ, Gejyo F, Ei I. The immunohistochemical localization of alpha2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein/fetuin-A (AHSG) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:851–852. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hruska KA, Mathew S, Saab G. Bone morphogenetic proteins in vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2005;97:105–114. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.00000175571.53833.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young B, Gleeson M, Cripps AW. C-reactive protein: A critical review. Pathology. 1991;23:118–124. doi: 10.3109/00313029109060809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang K, Weiss D, Suo J, Vega JD, Giddens D, Taylor WR, et al. Bone morphogenic protein antagonists are coexpressed with bone morphogenic protein 4 in endothelial cells exposed to unstable flow in vitro in mouse aortas and in human coronary arteries: role of bone morphogenic protein antagonists in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2007;116:1258–1266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bostrom K, Watson KE, Horn S, Wortham C, Herman IM, Demer LL. Bone morphogenetic protein expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1800–1809. doi: 10.1172/JCI116391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman RL, Tong I, Beardmore TD. Prosthetic synovitis: clinical and histologic characteristics. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:1066–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter JM, Jaeger SH, Matsui T, Miyaji N. The pseudosynovial sheath--its characteristics in a primate model. J Hand Surg Am. 1983;8:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fowler MR, Nathan CO, Abreo F. Synovial metaplasia, a specialized form of repair. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:727–730. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0727-SMASFO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbondanzo SL, Young VL, Wei MQ, Miller FW. Silicone gel-filled breast and testicular implant capsules: a histologic and immunophenotypic study. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:706–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siggelkow W, Faridi A, Spiritus K, Klinge U, Rath W, Klosterhalfen B. Histological analysis of silicone breast implant capsules and correlation with capsular contracture. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loeser RF, Wallin R. Cell adhesion to matrix Gla protein and its inhibition by an Arg-Gly-Asp-containing peptide. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9459–9462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishimoto SK, Nishimoto M. Matrix Gla protein C-terminal region binds to vitronectin. Co-localization suggests binding occurs during tissue development. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilbert KA, Rannels SR. Matrix GLA protein modulates branching morphogenesis in fetal rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1179–L1187. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00188.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolfram D, Rainer C, Niederegger H, Piza H, Wick G. Cellular and molecular composition of fibrous capsules formed around silicone breast implants with special focus on local immune reactions. J Autoimmun. 2004;23:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berry MG, Cucchiara V, Davies DM. Breast augmentation: Part II--Adverse capsular contracture. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:2098–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]