BACKGROUND

Excessive ear wax can lead to symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus, itching, vertigo, and pain. Treatment to remove ear wax is generally carried out in primary care, and recent estimates suggest that up to 2 million ear irrigations are performed in England and Wales each year.1 This places a considerable demand on GP surgeries.

A range of simple and often inexpensive remedies and proprietary drops can be used either to dissipate the wax orsoften it prior to removal. Although removal through irrigation usually occurs in primary care, some people may self-treat. Treatments offered often appear to be based on custom and local practice, rather than an awareness of the comparative effectiveness and costs of the different alternatives. Although evidence on the efficacy of different treatments has been published, no study has examined both clinical and cost-effectiveness. This report summarises a systematic review and economic evaluation of different approaches to ear wax removal taken from a UK perspective.

METHOD

Eleven electronic databases including Cochrane, MEDLINE, and Embase were searched until November 2008. Using prespecified criteria, studies of any treatment for the removal of ear wax, in any population, were included. Outcomes included hearing loss, adequacy of clearance, quality of life, and adverse events. Studies were randomised controlled trials or controlled clinical trials. Two reviewers selected studies, extracted data, and assessed methodological quality, and studies were synthesised narratively.

Existing economic evaluations were also searched for and an exploratory economic evaluation was undertaken. The model estimated the cost-effectiveness of softeners followed by irrigation in primary care, and softeners followed by self-irrigation, relative to no treatment and to each other. An NHS perspective for the estimation of benefits and costs was assumed. The study focused on an adult population and assessed outcomes over different time horizons. Only the estimates of the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained are reported here.

RESULTS

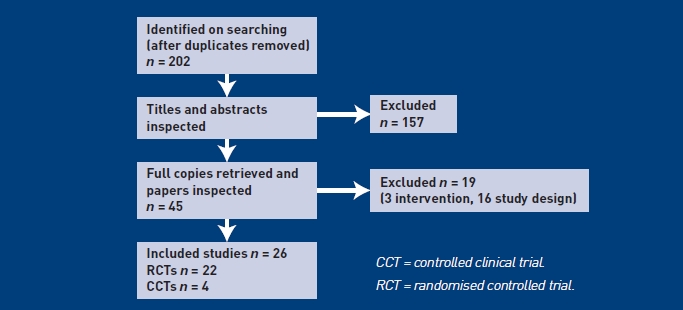

Twenty-six clinical trials conducted in primary care (14 studies), secondary care (eight studies), or other care settings (four studies) were included from an initial 188 identified references (Figure 1). A range of interventions were used in the studies, including different softeners and/or irrigation. The timing of interventions and follow-up assessments varied. Characteristics of participants and choice of outcome measures also differed between the studies. Patient-relevant outcomes were mostly subjective measures of occlusion, presence of symptoms, and adverse events. Lack of homogeneity in methods, interventions, and measures of outcomes precluded any meaningful evidence synthesis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of identification of studies for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness.

When considering only studies undertaken in primary care, and ignoring methodological shortcomings, there appears to be some evidence of comparative benefits between different interventions (Appendix 1). However, it is not possible to say that any one type of softener is superior, based on the evidence available.

Exploratory economic modelling of the lifetime cost-effectiveness of softeners followed by self-irrigation and softeners followed by professional irrigation, compared with no treatment, suggest incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) of £24 450 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 16 920 to 33 790) and £32 136 (95% CI = 19 531 to 45 864) per QALY gained respectively. When comparing the two active treatments with each other, the estimated ICER is more than £335 000 per QALY gained. This suggests that softeners followed by self-irrigation were more likely to be cost-effective than softeners followed by irrigation in primary care, when compared with no treatment. A number of sensitivity and threshold analyses were undertaken. The results did not appear to be sensitive to the variation in the cost of self-irrigation, but were sensitive to variation in the estimates of clinical effectiveness of softeners and the utility associated with hearing loss. Caution is required in the interpretation of the results of the economic model, because of the paucity of reliable data used to populate it.

DISCUSSION

The study found limited good-quality evidence, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the various methods for removing ear wax. Although the study was able to show that softeners have an effect in clearing earwax in their own right and as precursors to irrigation, it remains uncertain which specific softeners are superior. While caution should be taken in interpreting the results of the economic evaluation, the study shows that self-irrigation is likely to be more cost-effective than professional irrigation. The generalisability of the results, however, depends on how the clinical pathways assumed in the model are representative of typical clinical practice, as these are known to vary.

This findings are generally in line with previous systematic reviews in this area. However, this review differed because it assessed studies by setting, the intention for use of the softener, the populations, and the follow-up. It assessed all methods of treatment, including self-syringing; assessed all available preparation comparisons; and each study was assessed for methodological quality. The research was undertaken to fill an evidence gap identified as important by an expert advisory panel of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme, so that practitioners could be best informed about treatments for ear wax.

Given the large number of people attending primary care with earwax, it was surprising to find such limited good-quality evidence. There was little in the way of consistency among the included studies and many studies omitted basic data. This cannot be completely accounted for by the age of the publications, as many have been published since the advent of reporting standards for trials. While rigorous, consistent methods of critical appraisal and presentation were applied in this study, these factors made it difficult to summarise the results in a meaningful way.

Further research is required to improve the evidence base before policy and practice can be reliably informed. Ideally, a well-conducted randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation could provide an assessment of the different ways of providing the service (that is, practice nurse provision versus self-syringing) as well as the effectiveness of the different methods of removal. As part of this, it would be important to assess first the acceptability of different approaches, to ensure the most appropriate research structure.

Appendix 1.

Details of included studies undertaken in primary care settings

| Study details | Comparison | Key measure (s) | Statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Audax® | |||

| Lyndon et al,2 | |||

| RCT | 1. Audax® (n = 19) | Degree of impaction: none, mild, moderate, or severe | Not statistically significant (no P-value reported) |

| Age, mean (range) years: 52 (19–86) overall | |||

| Sex, M:F for all patients: 19:17 | 2. Earex® (n = 17) | Ease of syringing: not required, easy, difficult, or impossible | Statistically significant in favour of Audax® (P<0.005) |

| Follow-up: 5 days | |||

| Cerumol® | |||

| Fahmy and Whitefield,3 | |||

| CCT | 1. Cerumol® (ears = 157) | Wax dispersal without syringing | Statistically significant in favour of Exterol® (P<0.001) |

| Age: not reported | |||

| Sex: not reported | 2. Exterol® (ears = 129) | ||

| Follow-up: 1 week | |||

| Jaffé and Grimshaw,4 | |||

| RCT | 1. Cerumol® (n = 53) | Number of people needing syringing | Statistically significant in favour of Otocerol® (P = 0.05) |

| Baseline characteristics: | |||

| Age distribution (Group 1:Group 2): | 2. Otocerol® (n = 53) | ||

| 0–9 years: 0:1 | |||

| 10–19 years: 5:1 | |||

| 20–59 years: 31:35 | |||

| 60–89 years: 17:16 | |||

| Sex, M:F: | |||

| 1. 32:21 | |||

| 2. 25:28 | |||

| Follow-up: patients asked to revisit GP after three instillations | |||

| General Practitioner Research Group,5 | |||

| RCT | 1. Waxsol® (n = 47) | Volume of water for syringing | Not reported |

| Age groups, % of all patients: | |||

| 10–30 years, 27 | 2. Cerumol® (n = 60) | Ease of wax removal | Not reported |

| 31–50 years, 34 | |||

| 51–70 years, 31 | |||

| 71 years and over, 8 | |||

| Sex: not reported | |||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Dummer et al,6 | |||

| RCT | 1. Audax® (n = 27) | Amount, colour, and consistency of wax | Not reported |

| Age, mean years: | |||

| 1. 51 | 2. Cerumol® (n = 23) | ||

| 2. 55 | |||

| Sex, M:F: | |||

| 1. 18:9 | |||

| 2. 14:9 | |||

| Follow-up: median number of days between visits 1 and 2 was 4 days (range 3–7 days) | |||

| Triethanolamine polypeptide | |||

| Singer et al,7 | |||

| RCT | 1. DS (n = 27) | TM visualisation: complete or incomplete | Not statistically significant |

| Age, mean years (SD): | |||

| 1. 38.7 (30.7) | 2. TP (n = 23) | ||

| 2. 46.1 (29.1) | |||

| Sex, M:F (%): | |||

| 1. 16 (59):11 (41) | |||

| 2. 16 (70):7 (30) | |||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Meehan et al,8 | |||

| RCT | 1. DS (n = 15) | TM visualisation: complete, partial, clear | Not reported |

| Age, mean years: 4.6 overall | |||

| Sex, M:F overall: 24:24 | 2. TP (n = 17) | ||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Also saline alone group (n = 16) | |||

| Whatley et al,9 | |||

| RCT | 1. DS (n = 35) | TM visualisation: complete | Not reported |

| Age, mean (SD): | |||

| 1. 36.4 (19.1) monthsa | 2. TP (n = 30) | ||

| 2. 30.9 (15.2) months | |||

| Sex, M:F (%): | Also saline alone group (n = 28) | ||

| 1. 14:20 (41:59) | |||

| 2. 13:17 (43:57) | |||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Amjad and Scheer,10 | |||

| RCT | 1. TP (n = 40) | Degrees of wax removal | Not reported |

| Age: not reported | |||

| Sex: not reported | 2. Carbamide peroxide (n = 40) | ||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Sodium bicarbonate preparations | |||

| Carr and Smith,11 | |||

| RCT | 1. Aqueous sodium bicarbonate (n = 35) | Mean change in degree of cerumen | Not statistically significant (no P-value reported) |

| Age, mean years for all: | |||

| 27.0 | |||

| 25.3 | 2. Aqueous acetic acid (n = 34) | ||

| Age, mean years for children: | |||

| 1. 8.7 | |||

| 2. 7.26 | |||

| Sex: not reported | |||

| Follow-up: 14 days | |||

| Dioctyl-medo | |||

| General Practitioner Research Group,12 | |||

| RCT | 1. Dioctyl-medo (n = 77) | Volume of water for syringing | Not reported |

| Age range, overall, years | |||

| M: 31–50 | 2. Oil-base alone (n = 73) | Ease of wax removal | |

| F: 51–70 | |||

| Sex, all patients, M:F 1.3:1 | |||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

| Burgess,13 | |||

| CCT | 1. Dioctyl-medo (n = 33 ears) | Ease of removing wax | Not reported |

| Age range, years: 18–75 overall | |||

| Sex, M:F for all patients: 32:18 | 2. Maize oil capsules (n = 41 ears) | ||

| Follow-up: 2–7 days | |||

| Water | |||

| Eekhof et al,14 | |||

| RCT | |||

| Age, mean years (SD): 51 (16) overall | 1. Water (n = 22) | Mean number of syringing attempts | Not statistically significant (P = 0.18) |

| Sex, M:F overall: 20:22 | |||

| Follow-up: immediate for water group but 3 days for oil group | 2. Self-administered oil (n = 20) | ||

| Pavlidis and Pickering,15 | |||

| RCT | 1. Wet syringing (n = 22 ears) | Mean number of syringing attempts | Not tested |

| Age, mean years (SD): | |||

| 1. 63 (8) | 2. Dry syringing (n = 17 ears) | ||

| 2. 65 (20) | |||

| Sex, M:F (%): | |||

| 1. 15 (68):7 (32) | |||

| 2. 11 (65):6 (35) | |||

| Follow-up: immediate | |||

One participant discontinued. CCT = controlled clinical trial. DS = docusate sodium. F = female. M = male. RCT = randomised controlled trial.

SD = standard deviation. TM = tympanic membrane. TP = triethanolamine polypeptide.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme, project reference 06/77/04, and has been published in full in Health Technology Assessment 2010; 14: 28. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Grossan M. Cerumen removal — current challenges. Ear Nose Throat J. 1998;77(7):541–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyndon S, Roy P, Grillage MG, Miller AJ. A comparison of the efficacy of two ear drop preparations (‘Audax’ and ‘Earex’) in the softening and removal of impacted ear wax. Curr Med Res Opin. 1992;13(1):21–25. doi: 10.1185/03007999209115218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahmy S, Whitefield M. Multicentre clinical trial of Exterol as a cerumenolytic. Br J Clin Pract. 1982;36(5):197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffé G, Grimshaw J. A multicentric clinical trial comparing Otocerol with Cerumolas cerumenolytics. J Int Med Res. 1978;6(3):241–244. doi: 10.1177/030006057800600312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.General Practitioner Research Group. Wax softening with a new preparation. Practitioner. 1967;199(191):359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dummer DS, Sutherland IA, Murray JA. A single-blind, randomized study to compare the efficacy of two ear drop preparations (‘Audax’ and ‘Cerumol’) in the softening of ear wax. Curr Med Res Opin. 1992;13(1):26–30. doi: 10.1185/03007999209115219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer AJ, Sauris E, Viccellio AW. Ceruminolytic effects of docusate sodium: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(3):228–232. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.109166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meehan P, Isenhour JL, Reeves R, Wrenn K. Ceruminolysis in the pediatric patient: a prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial [abstract] Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(5):521–522. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whatley VN, Dodds CL, Paul RI. Randomized clinical trial of docusate, triethanolamine polypeptide, and irrigation in cerumen removal in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(12):1177–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amjad AH, Scheer AA. Clinical evaluation of ceruminolytic agents. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1975;54(2):76–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr MM, Smith RL. Ceruminolytic efficacy in adults versus children. J Otolaryngol. 2001;30(3):154–156. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.General Practitioner Research Group. A wetting agent to facilitate ear syringing. Practioner. 1965;195(170):810–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess EH. A wetting agent to facilitate ear syringing. Practitioner. 1966;197(182):811–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eekhof JA, de Bock GH, Le Cessie S, Springer MP. A quasi-randomised controlled trial of water as a quick softening agent of persistent earwax in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(469):635–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlidis C, Pickering JA. Water as a fast acting wax softening agent before ear syringing. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(4):303–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]