Abstract

Background

Hypomorphic mutations in the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) gene result in a variable syndrome of somatic and immunological abnormalities. Clinically relevant genotype-phenotype associations are essential to understanding this complex disease.

Objective

Two unrelated boys with novel NEMO mutations altering codon 223 were studied for similarity in phenotype in consideration of potential genotype-phenotype associations.

Methods

Clinical and Laboratory features including cell counts, immunoglobulin quantity and quality, NK cell cytotoxicity, Toll-like and TNF receptor signaling were evaluated. Since both mutations affected NEMO codon 223 and were novel, consideration was given to new potential genotype-phenotype associations.

Results

Both patients were diagnosed with hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia and had severe or recurrent infections. One had recurrent sinopulmonary infections and the other necrotizing soft tissue MRSA infection and Streptococcus anginosus subdural empyema with bacteremia. NEMO gene sequence demonstrated a three-nucleotide deletion (c.667_669delGAG) in one patient and a substitution (667G>A) in the other. These predict either the deletion of NEMO glutamic acid 223 or it being replaced with lysine, respectively. Both patients had normal serum IgG levels but poor specific antibodies. NK cell cytotoxicity, Toll-like and TNF receptor signaling was also impaired. Serious bacterial infection did not occur in both patients after immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Conclusions

Two different novel mutations affecting NEMO glutamic acid 223 resulted in clinically relevant similar phenotypes providing further evidence to support genotype-phenotype correlations in this disease. They suggest NEMO residue 223 is required for ectodermal development and immunity and is apparently dispensable for quantitative IgG production, but may be required for specific antibody production.

Keywords: Primary Immunodeficiency, Innate Immunity, Bacterial Infection

Introduction

Ectodermal dysplasia with anhidrosis (EDA) is a group of related syndromes resulting from aberrant development of ectodermal tissues. It is characterized by fine sparse hair, conical or missing teeth, dysplastic nails, periorbital skin wrinkling, and a lack of eccrine sweat glands.1 A variety of forms of EDA exist with known genetic causes. Isolated EDA is due to genetic mutations affecting the TNF superfamily member Ectodysplasin A (ED1), its receptor (EDAR), or the EDAR associated death domain containing adaptor protein EDARADD. A related syndrome is associated with impaired immunity resulting in severe or recurrent infections and is known as EDA-ID, or more recently NEMO-ID or NEMO Syndrome (to reflect the occasional absence of an accompanying ectodermal defect).2 Genetic lesions in this form affect the IKBKG gene, which encodes the NF κ-B essential modulator (NEMO) and is also referred to as the NEMO gene. The EDA-ID syndrome can also and much more infrequently result from mutation of NFΚBIA, which encodes IκBα, the Inhibitor of NF-κB, alpha.1

NEMO is a 419 amino acid regulatory protein encoded by 10 exons on the X chromosome.3 NEMO is the catalytically inactive subunit of the Inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK) complex, which is required for canonical pathway activation of the NF-κB family of transcription factors. NFκB is found in most cells and functions to regulate the transcription of genes involved in development, immunity, inflammation, cell growth and programmed death.4 NF-κB is typically retained in the cytoplasm of cells bound to IκB, but can translocate to the nucleus to promote transcription after IκB is phosphorylated. In the absence of NEMO, the IKK complex is inactive, and hence unable to phosphorylate IκBα, thus blocking NF-κB activation as it is unable to become free of its inhibitor to translocate into the nucleus. Mutations that partially disrupt NEMO activity (hypomorphic mutations) result in impaired NF-κB activation leading to both humoral and cellular immune abnormalities in an X-linked recessive pattern since under normal circumstances a single functional copy in mothers is sufficient to enable IKK activity. Some NEMO function, however, is a prerequisite for in utero development, and thereby males inheriting a NEMO gene that completely interrupts NEMO function are not viable. Thus all known NEMO gene mutations resulting in NEMO-ID are hypomorphic.

The clinical and immunologic phenotypes attributed to NEMO hypomorphism were recently reviewed.2 Despite clinical variability of disease expression, which is inherent in human genetic disease due to genomic and environmental variability, patterns are emerging in which specific phenotypes are suggestive of specific mutations. For example, among the mutations, which have appeared in more than one individual, the classic Hyper-IgM syndrome phenotype (low immunoglobulin production, normal or elevated IgM and a deficiency in specific IgG production, class switching, and B cell activation) is seen only in individuals with mutations at cysteine 417. In contrast, mutation in the NOA/UBAN/NUB domain (residues 289–320) in 100% (6/6) of cases leads to (6/6) mycobacterial susceptibility compared to 37% (9/24) with mutations outside this region. Furthermore, 100% (6/6) have normal immunoglobulin levels and production of specific antibodies compared to only 12% (15/17) that have mutations outside of this region. Comparison of these two genotypic patterns suggests clinically relevant phenotypic associations, and raises the importance of further work in this disease with regards to genotypes and phenotypes. Irrespective, we have proposed that detailed phenotypic characterization will lead to improved prognostic information and patient management.2

Here we report two unrelated boys with novel NEMO mutations within exon 5, which result in predicted amino acid changes at Glutamic acid 223. Both had ectodermal dysplasia characteristics, similar infectious susceptibilities and similar immune abnormalities with normal total IgG levels. We studied their clinical and immunologic characteristics including endogenous antibody production and, ex-vivo, TNF and Toll-like receptor signaling. Since mutations affecting this specific residue within NEMO have not been previously described, further consideration was given to a potenital genotype-phenotype association.

Methods

Parental Consent

Investigations of the patients were performed under an IRB approved protocol of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Parents of both patients provided written informed consent for this research.

Immunologic assays

Serum immunoglobulin concentrations, determined by nephelometry, were measured in the LSU Health Sciences Center Children’s Hospital Immunology Laboratory and compared with age-related normal values. The number and percentage of lymphocytes in various subsets were compared with age-related normal values. Mitogen-induced proliferation was performed using phytohemagglutinin, pokeweed, and concavalin A and antigen-induced proliferation to tetanus, Candida, and diphtheria was similarly tested.

NEMO sequence analysis

Genomic DNA sequencing of patient 1 was performed by PCR amplification, with sequencing of entire coding region and long range PCR of the NEMO pseudogene by Correlagen Laboratory (Waltham, MA). Genomic DNA analysis of patient 2 was performed in the Clinical Immunology Unit, NIAID Bethesda, MD.

TLR function assay

TLR function assay was performed as previously described5. Briefly, mononuclear cells isolated from whole blood were incubated with media or ligands to TLR1/2, 2/6, 3,4,5,7/8 with subsequent measurement of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the supernatant by Luminex multiplex assay using cytokine detection kits from either R&D systems (Fluorkine) or Millipore (Miliplex).

NK cell studies

NK cell cytotoxicity was evaluated on the basis of 51-Cr release from radiolabeled K562 erythroleukemia cells as described previously6. Briefly, K562 cells were labeled by incubation with 51Cr (Na2CrO4) (Perkin–Elmer) at 37°C. Labeled target cells were mixed with NK cells at specified effector-to-target cell ratios and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. 51Cr released into supernatants was measured, and percentage lysis was determined. Cytotoxicity was reported as LU20 NK, which is defined as the number of effector cells (expressed in 107) required to achieve 20% lysis of target cells per ten million natural killer cells.

TNFα induced IκBα degradation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the patient and a healthy control were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque lymphocyte separation media. 5 × 105 cells per condition were stimulated with TNFα and lysed after 0, 10 and 60 minutes. Cells were then heated in SDS lysis buffer following the addition of protease inhibitor cocktail as previously described. Following denaturing protein electrophoresis of lysates, protein was detected with rabbit polyclonal anti-IκBα. In order to demonstrate equal loading of samples, the membrane was stripped and reprobed for total actin using anti-Myosin-IIB antibody. Quantitation of IκBα and actin for each lane was performed by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software (NIH, freeeware). Ratios of IκBα band intensity were calculated and depicted graphically in adjacent histograms to facilitate interpretation of the results.

Results

Case Report – patient 1

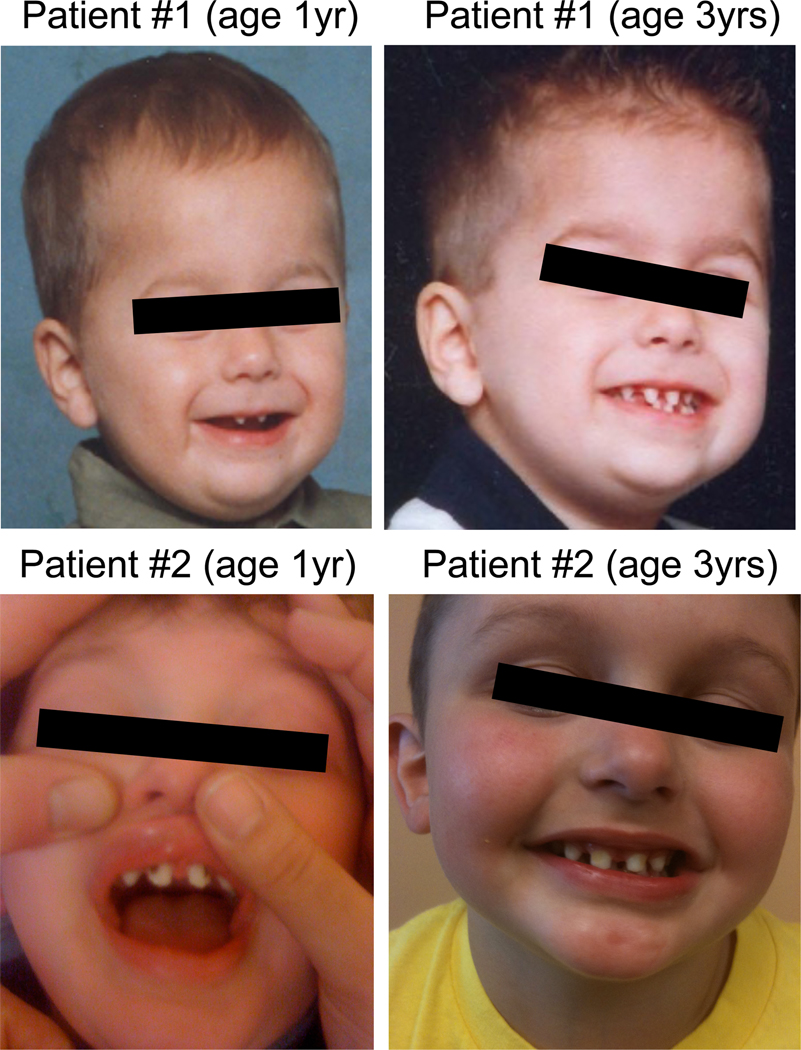

Patient 1 is a five-year-old male born to unrelated Caucasian parents. He had recurrent sinopulmonary infections beginning prior to one year of age and hospitalization on two occasions due to bacterial pneumonia. He had mildly conical shaped teeth and hypohidrosis, consistent with ectodermal dysplasia. An immunological evaluation at 4 years of age revealed normal IgG,(1035 mg/dL;423–1184 mg/dL) low IgM (37mg/dL; normal 48–168 mg/dL) and elevated IgA (169 mg/dL; 24–121 mg/dL) levels. IgG subclass levels were within normal limits. Serum antibodies titers to Diphtheria toxoid were low normal, and antibodies against S. pneumonia were protective to only one of the eleven serotypes longitudinally tested after four doses of Prevnar (PCV7; the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine). He had a normal distribution of lymphocyte subsets, and in vitro lymphocyte proliferation in response to both mitogens and antigens was within normal limits. Subsequent to this testing, he was vaccinated with the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax; PPV23), and when tested six-weeks later, titers against four of these eleven previously tested serotypes had risen into protective ranges (Table 1). TLR-ligand induced cytokine production was decreased in response to all agonists tested. NK cell cytotoxicity was reduced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Initial immunologic laboratory values in two patients with NEMO residue 223 alteration.

| Laboratory value | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

|---|---|---|

| IgG (423–1184 mg/dL) a | 1035 | 735 |

| IgA (25–154 mg/dL) | 169 ↑ | 151 |

| IgM (48–168 mg/dL) | 37 ↓ | 34 ↓ |

| IgE (0–60 IU/mL) | <4 | <4 |

| Tetanus Titer | <0.10 | 0.19 |

| Diphtheria Titer | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Pneumococcal Titer pre-vaccination | 1 - 1.1 | N.D.c |

| 3 - 0.4 | ||

| 4 - <0.6 | ||

| 6b - 0.5 | ||

| 7f - 0.5 | ||

| 9 - 0.1 | ||

| 12f - 0.4 | ||

| 14 - <0.5 | ||

| 18C - <0.5 | ||

| 19f - <0.4 | ||

| 23f - <0.3 | ||

| Pneumococcal Titer 6 weeks post vaccination | 1 - 0.51 | N.D. |

| 3 - 6.43 | ||

| 4 - 0.37 | ||

| 6b - 0.45 | ||

| 7f - 0.27 | ||

| 9 - 0.17 | ||

| 12f - 1.73 | ||

| 14 - 2.12 | ||

| 18C - 0.41 | ||

| 19f - 0.90 | ||

| 23f - 1.43 | ||

| NK cell cytotoxicity (LU20 >317) | 47.6 | 172.6 |

| Abs CD3+ (2100–6200) b | 3820 | 4933 |

| Abs CD4+ (1300–3400) | 2490 | 3603 |

| Abs CD4/CD45RA | N.D. | 3486 |

| Abs CD4/CD45RO | N.D. | 338 |

| Abs CD8+ (620–2000) | 1220 | 1158 |

| Abs CD19+ (600–2700) | 660 | 1998 |

| CD19+/CD27+/IgD+d | N.D. | 20.3% |

| CD19+/CD27+/IgD−d | N.D. | 2.1% |

| CD19+/IgD+/IgM+d | N.D. | 89.9% |

| CD16/56+ (180–920) | 720 | 345 |

Age-specific normal values are shown in parentheses

Subset counts (number of cells per microliter)

N.D. = not done

Expressed as percentage of total CD19+ cells

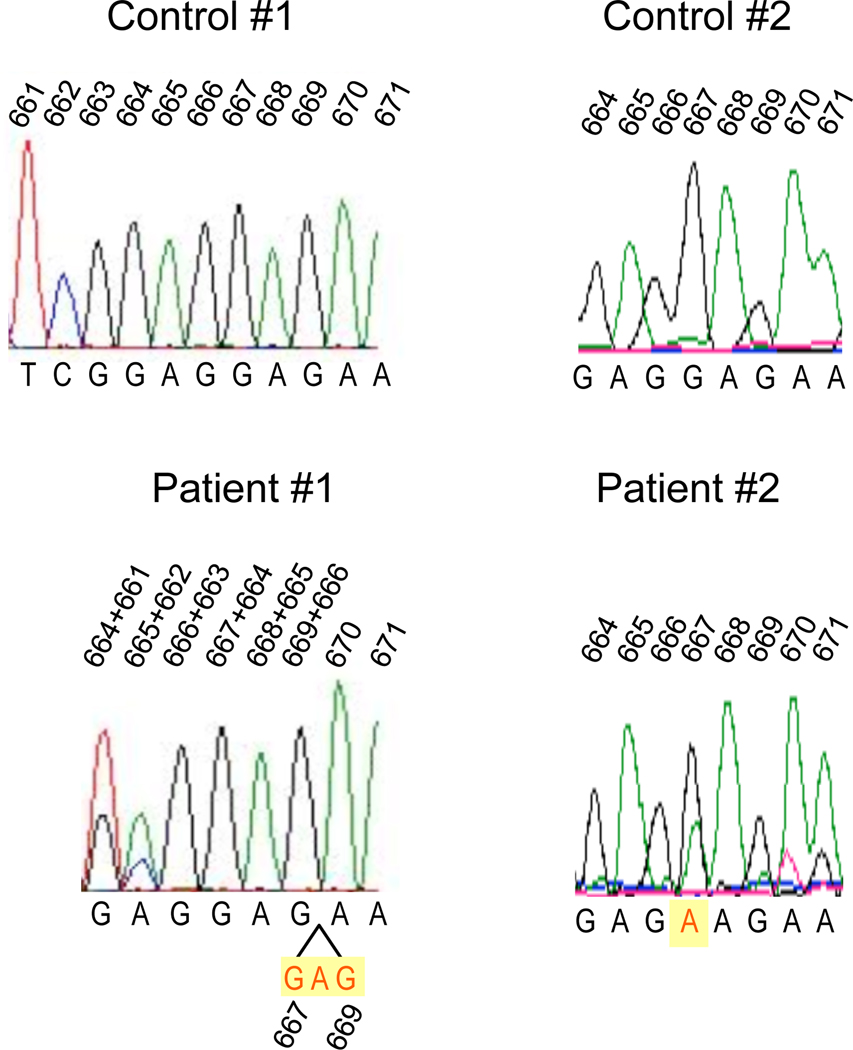

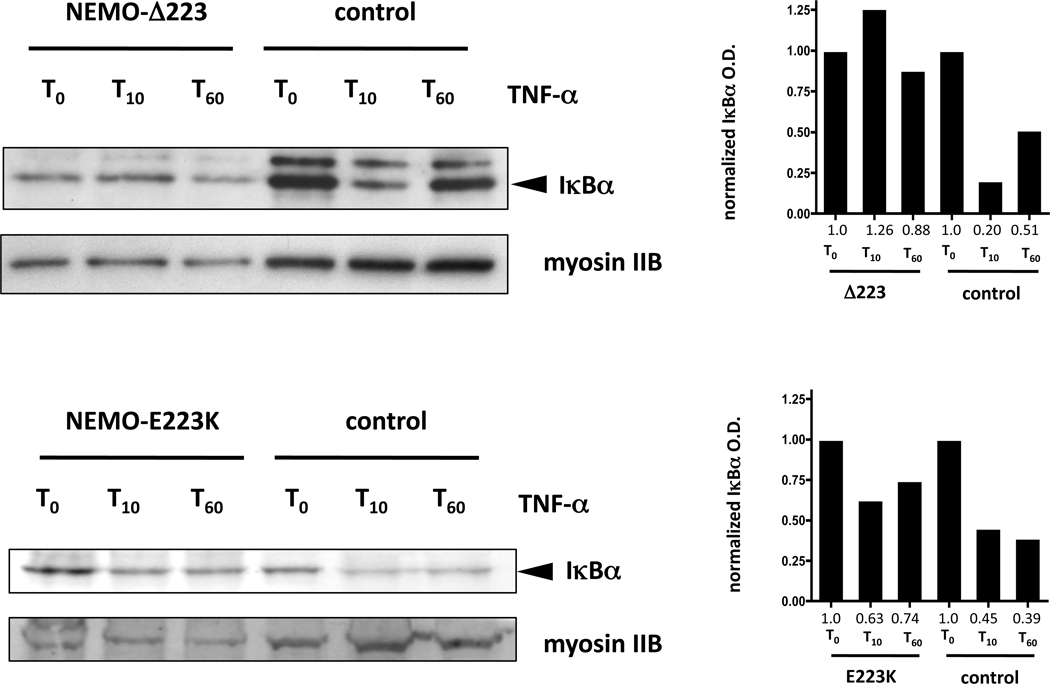

Because of the combination of infectious disease history, ectodermal features and functional studies, we sought molecular genetic analysis of the NEMO gene. Sequencing revealed a novel 3 nucleotide deletion, c.667_669delGAG (Figure 2) predicting the deletion of glutamic acid at position 223 (Δ223). The patient’s mother and one sister were found to be carriers of this mutation. Because NEMO hypomorphic mutations have been shown to have differential effects on NF-κB activation in response to stimulation with different immune receptors,2 we sought to further characterize the immune signaling phenotype in this individual. To determine the integrity of the signaling pathway downstream of TNF receptor, primary mononuclear cells were isolated from the peripheral blood and left in media or stimulated with TNFα for 10 and 60 minutes. Following this treatment, lysates were derived, separated by gel electrophoresis, and Western blot analysis performed to measure IκBα degradation at different time points (Figure 3). Stimulation of control donor PBMC with TNFα for 10 minutes resulted in reduction of IκBα levels (lane 5), which was normalized to myosin IIB levels, quantitated by optical densitometry and determined to be reduced by 80% (right). The patient PBMC were unable to respond to TNF stimulation as evidenced by complete lack of IκBα degradation (lane 2).

Figure 2.

Genomic sequencing tracings of the individuals with IKBKG mutation. The genomic DNA sequence tracings of two normal controls (top tracings) and two patients with mutations predicting ΔE223 (patient 1, bottom left) and E223K (patient 2, bottom right) NEMO protein. Genomic sequences were obtained from genomic DNA generated from PBMCs via long-range polymerase chain reaction. In patient 1 the tracing demonstrates a “shift to the right” so that with the nucleotides are superimposed as listed indicative of a tri-nucleotide deletion c.667_669delGAG (depicted in yellow, below) and due to coincidence with the NEMO pseudogene. In patient 2, c.667G>A is indicated by the red “A”, which denotes the purine substitution (highlighted with the yellow rectangle, bottom right). The two peaks in the patient tracing demonstrate coincident signal from the actual and pseudogene in these original data. The numbers above the sequences denote the cDNA reference sequence used throughout which corresponds to 19416–19423 in the genomic reference.

Figure 3.

TNF-α-induced IκBα degradation time-course in patient and control PBMC. PBMC from the patients containing the mutant NEMO-ΔE223 (top left) and NEMO-E223K (bottom left), or from healthy control donors (top and bottom right) were stimulated with 10µg/mL human recombinant TNF for the specified times. Cell lysates were separated using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then evaluated via Western blot analysis for the presence of IκBα. To evaluate protein loading, membranes were stripped and reprobed for myosin-IIB. In the NEMO-ΔE223 analysis control IκB bands are darker at least in part due to protein loading as demonstrated by increased myosin-IIb signal. The lower band, in the IκB Western Blot analyses represents the IκBα protein and is denoted with an arrowhead. An upper band can be noted, which is a feature of sample handling, protein loading and length of electrophoresis, but is likely to contain phosphorylated IκBα. Densitometric analyses of the IκBα band (using the lower, major band) were performed and the measured values were normalized to those obtained in the unstimulated cells (to compensate for differences in protein loading between patient and control). Normalized densitometric measurements are shown in graphic format to the right of each Western blot analysis, with the values provided below each time point (red). These experiments were performed twice with the NEMO-ΔE223 and once for the NEMO-E223K patient cells. The data indicate that the patients with E223 mutations fail to effectively inactivate IκBα.

Case Report – patient 2

Patient 2 is a three-year-old male born to unrelated Caucasian parents. He was treated for a necrotizing soft tissue MRSA infection at 16 months of age, which resolved without sequelae. At 26 months, he was hospitalized with a left temporal lobe brain abscess and temporal convexity empyema, likely secondary to seeding from three rapidly progressive cavities in upper incisor teeth and a lower molar tooth, and left maxillary sinusitis. During this course he also experienced Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia. Physical examination of patient 2 was notable for sparse, conical shaped teeth consistent with mild features of ectodermal dysplasia (Figure 1) and the four cavities (Figure 1 – left) which progressed rapidly over 2 weeks until topical fluoride was applied as a temporizing measure every two weeks until oral health care was instituted 3.5 months later. An immunological evaluation at 2 years of age revealed normal concentrations of IgG (735 mg/dL; 423–1184 mg/dL), and IgA (151 mg/dL; 25–254 mg/dL) and low IgM (34 mg/dL; 48–168 mg/dL). Serum antibodies to tetanus and diphtheria antigens were low normal. Pneumococcal antibody titer levels were not evaluated before IVIG was begun, and so determination of specific antibody production to polysaccharide antigen was not made. The distribution of lymphocyte subsets was normal, but there were a paucity of CD27+/IgD− switched memory B cells and an abundance of IgD+/IgM+ naïve B cells (Table 1). Due to infection with S. anginosus, and subsequent concern for inability to generate superoxode, dihydrorhodamine 123 conversion in granulocytes was tested and was normal. NK cytotoxicity was abnormal (Table 1). Results of TLR testing demonstrated impaired response to all ligands. NEMO sequence analysis revealed that patient 2 has a missense mutation resulting in a nucleotide 667G>A substitution (Figure 2) which predicts the substitution of glutamic acid at position 223 with a lysine (E223K). TNF receptor signaling was evaluated as for patient 1. Control donor cells demonstrated a 55% reduction in IκBα ten minutes after stimulation (lane 5), as determined by densitometry, normalized to the loading control. By contrast, E223K PBMC demonstrated slightly less degradation of IκBα but more importantly levels that were near baseline by 60 minutes unlike in control cells where sustained degradation was identified. This suggests a lack of robustness in the TNF signal in the patient, but not control cells.

Figure 1.

Facial features of NEMO Syndrome in the two patients under consideration. Two images from patient 1 (top) and patient 2 (bottom) are shown with the first taken at one year of age (left) and the second at three years of age (right). The patients demonstrate ‘mild’ ectodermal dysplasia with frontal bossing and sparse, hypodontia and somewhat conical teeth. The caries evident in incisors of patient 2 at one year of age are not uncommon in ectodermal dysplasia and may represent a feature of the abnormal dentition.

Taken together, hypomorphic NEMO mutation at amino acid 223 resulting in deletion or substitution leads to a similar phenotype. Specifically it is associated with ectodermal dsysplasia and susceptibility to infections. TLR signaling was impaired with reduced TNF-induced IκBα degradation. E223 mutation did not result in hypogammaglobulinemina, but was associated with weak specific antibody titers and an impaired the ability to produce specific antibodies to polysaccharide antigen (in the one patient evaluated) without affecting mitogen and antigen induced lymphocyte proliferation.

After diagnosis of a NEMO mutation with functional abnormality, both patients were started on replacement immunoglobulin therapy and did not have recurrence of severe bacterial infection. Although both boys did not have preexisting evidence of mycobacterial infection, they were additionally maintained on mycobacteria prophylaxis with azithromycin and neither has had suggestions of disease caused by mycobacteria.

Discussion

We describe two previously unreported mutations of human NEMO associated with immunodeficiency and ectodermal dysplasia. These mutations both affect glutamic acid 223 resulting in deletion of the residue, or lysine substitution. Patient 1 had recurrent sinopulmonary infections and two hospitalizations for suspected bacterial pneumonia. Patient 2 had Staphylococcus aureus soft tissue infection in addition to Streptococcus anginosus subdural empyema and bacteremia. The organism has not previously been reported in NEMO-syndrome individuals, but has been reported in cases of individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and in secondary immunodeficiency states7. Due to the unusual features in both patients, NEMO-ID was suspected and diagnosed. Defective NK cell function was identified in our patients and is one of the most consistently observed immunologic defects in individuals with hypomorhic NEMO mutation, having been found in 10/10 different individuals with NEMO mutation previously reported2. Although not specific to NEMO-ID8, a deficiency of NK cell function can be a useful tool, which can be used to refine consideration of NEMO mutation. The infectious susceptibilities found in our patients, however, were likely other immunological impairments. We hypothesize that the infections occurred due to a combination of specific antibody deficiency and impairments in innate immunity including TLR and TNF receptor signaling. We believe therefore, that the susceptibility is likely to represent a combination of immune deficits because our patients’ severity of infections was disproportionate to what might be expected in routine specific antibody deficiency.

While mutations affecting position 223 are unprecedented for NEMO-ID, an L227P mutation, shared by three brothers, was associated with hypogammaglobulinemia, inability to make specific antibody following immunization with the 23 valent vaccine, and Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis leading to demise in the first decade9. Furthermore, L227P mutation was associated with chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal disease9. A phenotype ‘heat map’ of inflammatory disease has indicated a ‘hot spot’ of mutations affecting the second half of the first coiled coil domain and including the second alpha helix associated with the phenotype2. However, our patients with NEMO residue 223 alterations did not exhibit an overt inflammatory disease as part of the clinical phenotype. This could suggest a non-essential role for NEMO residue 223 in the development of inflammatory disease, or a milder impact of this particular residue within this region, which could result in delayed onset of inflammatory disease phenotype. Irrespective, these patients and the specific mutations are worthy of further study. In particular, it will be important to determine if there are differential associations with up- or downstream signaling intermediates with NEMO 223 vs. 227 variants. It is likely, however, to underscore the complex potential genotype-phenotype associations in this disease at a mechanistic level and necessitates additional investigations in consideration of biological and even clinical insights.

TNF-induced IκBα degradation was additionally evaluated in our patients to determine the extent to which the alteration at position 223 affects the diverse immune pathways known to be implicated in NEMO Syndrome. TNFR activation engages a distinct signaling cascade from TLR/TIR pathway receptors. TLR signaling was impaired due to both mutations, however a difference in TNFR signaling was observed. The deletion of residue 223 was associated with an inability to induce IκBα degradation, whereas the mutation resulting in E223K resulted in slightly reduced TNF-α–induced IκBα degradation. That some IκBα degradation occurred in E223K cells does not exclude the possibility of downstream defects in this pathway, as TNF and TLR induced gene expression and cytokine production have been reported in cells in which IκBα degradation is normal2,10. TLR vs. TNFR signaling impairment differences suggest upstream (and possibly downstream) components of these two signaling pathways interact differentially with this region of NEMO, or with another domain functionally related to E223. As an important task remains to discover how signaling by TLR/TIR domain containing receptor signaling through NEMO differs from TNFR or TCR signaling; differences such as the one described here provide a functional clue into the mechanism. That this clue provides no real insight into mechanism highlights the need to develop more comprehensive readouts to interrogate these signaling pathways and network perturbations due to NEMO mutation.

Diagnosis of NEMO mutations is challenging in patients with subtle or even without signs of hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia. 23% of patients with a NEMO mutation and immunodeficiency had no diagnosis of EDA2 in a recent review of 72 individuals. A higher percentage of patients had mild features of the syndrome, which can be overlooked until a serious immunodeficiency is suspected. Our patients in this report might have been considered to have had more “mild” features of HED, which further emphasizes the importance of following physical exam-derived clues in suspecting NEMO. At this point, however, there is no single clear indication suggesting the absolute certainty of NEMO mutations in suspected patients. It should be considered worthwhile to seek NEMO mutations in male patients with the Hyper IgM syndrome that do not have any of the other known mutations associated with this phenotype, or in boys with a mycobacterial infection who have a humoral abnormality of some type. It is not as clear when to pursue a NEMO mutation in a patient with isolated specific antibody deficiency or other mild immunoglobulin abnormalities. In the aforementioned review, defects in specific antibody production occurred in 64%, but only four individuals also had normal serum IgG levels. Mutations in these “atypical” individuals span an area including first and second coiled coils and C-terminal to the leucine zipper. Based on the clinical presentation of our two patients and those atypical patients previously reported, consideration of NEMO mutation in patients with suggestions of immunodeficiency and mild ectodermal abnormalities is reasonable. Recurrent or severe invasive infections, often including infection with polysaccharide encapsulated organisms and specific antibody deficiency with or without mycobacterial infection, however, should still be considered the sine qua non of the syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by NIH-AI-079731 to JSO, and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation (to JSO and RUS). EPH is an employee of the federal government.

Footnotes

Author contributions: GK-P and RUS diagnosed patient 1, EPH performed the experimental studies on both patients, RS and CEK diagnosed patient 2. GK-P, EPH and JSO wrote the manuscript. JSO directed the experiments. JSO and RUS conceived the study.

Potential conflicts of interest: GK-P, EPH, RS, and CEK report no relevant conflicts of interest. RUS and JSO have served as consultants to Baxter Healthcare, Talecris Biotherapeutics and CSL Bhering – manufacturers of therapeutic Ig with which the patients in this study were treated.

Contributor Information

Gital Karamchandani-Patel, Email: gitalmd@gmail.com, Louisiana State University.

Eric P. Hanson, Email: eric.hanson@niams.nih.gov, Autoimmunity Branch, National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Rushani Saltzman, Email: saltzmanr@email.chop.edu, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

C. Eve Kimball, Email: ekimball@aacpp.com, All About Children Pediatric Partners, Reading, PA.

Ricardo U. Sorensen, Email: rsoren@lsuhsc.edu, Louisiana State University.

Jordan S. Orange, Email: Orange@mail.med.upenn.edu, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Mikkola ML. Molecular aspects of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am. J. Med Genet. 2009;149A:2031–2036. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson EP, Monaco-Shawver L, Solt LA, et al. Hypomorphic nuclear factor-kappaB essential modulator mutation database and reconstitution system identifies phenotypic and immunologic diversity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.018. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aradhya S, Courtois G, Rajkovic A, et al. Atypical forms of incontinentia pigmenti in male individuals result from mutations of a cytosine tract in exon 10 of NEMO (IKK-gamma) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:765–771. doi: 10.1086/318806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deering RP, Orange JS. Development of a clinical assay to evaluate toll-like receptor function. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:68–76. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.1.68-76.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orange JS, Brodeur SR, Jain A, et al. Deficient natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with IKK-γ/NEMO mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1501–1509. doi: 10.1172/JCI14858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orimo H, Yamamoto O, Izu K, Murata K, Yasuda H. Four cases of non-clostridial gas gangrene with diabetes mellitus. Journal of UOEH. 2002;1(24):55–64. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.24.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orange JS, Ballas ZK. Natural killer cells in human health and disease. Clin. Immunol. 2006;118:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schweizer P, Kalhoff H, Horneff G, Wahn V, Diekmann L. Polysaccharide specific humoral immunodeficiency in ectodermal dysplasia. Klin Padiatr. 1999;211(6):459–461. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siggs OM, Berger M, Krebs P, et al. A mutation of Ikbkg causes immune deficiency without impairing degradation of IkappaB alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 16(107):3046–3051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915098107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]