Abstract

Urinary bladder wall muscle (i.e., detrusor smooth muscle; DSM) contracts in response to a quick-stretch, but this response is neither fully characterized, nor completely understood at the subcellular level. Strips of rabbit DSM were quick-stretched (5 ms) and held isometric for 10 s to measure the resulting peak quick-stretch contractile response (PQSR). The ability of selective Ca2+ channel blockers and kinase inhibitors to alter the PQSR was measured, and the phosphorylation levels of myosin light chain (MLC) and myosin phosphatase targeting regulatory subunit (MYPT1) were recorded. DSM responded to a quick-stretch with a biphasic response consisting of an initial contraction peaking at 0.24 ± 0.02-fold the maximum KCl-induced contraction (Fo) by 1.48 ± 0.17 s (PQSR) before falling to a weaker tonic (10 s) level (0.12 ± 0.03-fold Fo). The PQSR was dependent on the rate and degree of muscle stretch, displayed a refractory period, and was converted to a sustained response in the presence of muscarinic receptor stimulation. The PQSR was inhibited by nifedipine, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), 100 μM gadolinium and Y-27632, but not by atropine, 10 μM gadolinium, LOE-908, cyclopiazonic acid, or GF-109203X. Y-27632 and nifedipine abolished the increase in MLC phosphorylation induced by a quick-stretch. Y-27632, but not nifedipine, inhibited basal MYPT1 phosphorylation, and a quick-stretch failed to increase phosphorylation of this rhoA kinase (ROCK) substrate above the basal level. These data support the hypothesis that constitutive ROCK activity is required for a quick-stretch to activate Ca2+ entry and cause a myogenic contraction of DSM.

Index Words: smooth muscle, urinary bladder, rabbit, myogenic contraction, signal transduction, ROCK

1. Introduction

A transient detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) contraction in response to mechanical quick-stretch or a hypo-osmolar solution has been identified in rabbit (Burnstock and Prosser, 1960) and man (Masters et al., 1999). This transient contraction is also revealed as a transient increase in pressure when whole bladders are subjected to rapid, step increases in volume (Andersson et al., 1988). Stretch-induced smooth muscle contraction occurs independently of neural input, and the contractile response is therefore termed myogenic. A myogenic response is produced in many, but not all, smooth muscle types (Johnson, 1980), and has been most extensively studied in vascular smooth muscle, where the myogenic response plays a key role in regulation of blood flow (Davis and Hill, 1999). Membrane depolarization leading to elevations in Ca2+ entry and cytosolic Ca2+ levels can cause myogenic contraction, although the upstream mechanisms leading to depolarization remain to be fully elucidated (Davis and Hill, 1999). In DSM, activation of non-selective cation channels (Wellner and Isenberg, 1994) and stretch-dependent ryanodine receptors (Ji et al., 2002) have been shown to participate in stretch-mediated myogenic contraction. In addition to Ca2+-dependent mechanisms, there is evidence that ROCK, protein kinase C (PKC), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nitric oxide participate in myogenic contraction (Lagaud et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2008).

The precise role that stretch-activated myogenic contraction plays in the regulation of bladder filling or in micturition remains to be determined. However, not every DSM cell is innervated by a post-ganglionic parasympathetic fiber. For this reason Elbadawi (Elbadawi, 1995) suggested that rapid shortening (contraction) of innervated DSM cells following nerve activation leads through mechanical coupling to myogenic activation and contraction of many non-innervated muscle cells, and thus, to a complete and uniform detrusor contractile response. This concept was recently supported by Ji et. al. (Ji et al., 2002). Moreover, myogenic contraction may play a role in the spontaneous (autonomous) rhythmic contraction that occurs during the bladder filling phase (Gillespie, 2004).

The signaling events acting downstream from stretch-activated release of intracellular Ca2+ (Ji et al., 2002) that are responsible for causing DSM contraction remain to be determined. In particular, multiple Ca2+ entry channels potentially participate in smooth muscle Ca2+ homeostasis and contraction (Beech et al., 2004), and contraction may be regulated not only by increases in Ca2+, but also by increases in the sensitivity of contractile proteins to Ca2+ (Ratz et al., 2005; Somlyo and Somlyo, 2003). The present study was designed to characterize biomechanically the myogenic contraction produced in rabbit DSM in response to an imposed rapid length-step (quick-stretch), and to identify subcellular mechanisms linking muscle-stretch with the myogenic contractile response.

Overactive bladder is a disorder involving involuntary detrusor contractions that occur during bladder filling (Hampel et al., 1997). Although overactive bladder is a complex disorder that may be associated with several different conditions, one unifying concept proposed by Coolsaet and Blaivas (Coolsaet and Blaivas, 1985) and shown recently to occur in intact bladder (Gillespie et al., 2003; Streng et al., 2006) is that detrusor is never entirely inactive (Artibani, 1997), and a defect causing accentuated micro-motion would propagate a chain of events that may trigger urinary urge incontinence and related symptoms (Gillespie, 2004). Indeed, detrusor from patients with overactive bladder display enhanced spontaneous rhythmic contractile tone (Kinder and Mundy, 1987). Moreover, partial bladder outlet obstruction enhances the autonomous activity of discreet bundles of DSM, and coordination of these contractions is enhanced by stretch (Drake et al., 2003). By understanding the subcellular events associated with myogenic contractions, a means to therapeutically modulate detrusor overactivity may be discovered that would provide effective treatment of urge incontinence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Tissue preparation

All experimental protocols involving animals were conducted within the appropriate animal welfare regulations and guidelines and were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Tissues were prepared as described previously (Speich et al., 2005). Whole bladders from adult female New Zealand white rabbits were removed immediately after sacrifice with pentobarbital. The bladders were washed several times, cleaned of adhering tissue, including fat and serosa, and stored in cold (0–4°C) physiologic salt solution (PSS), composed of NaCl, 140mM; KCl, 4.7 mM; MgSO4, 1.2 mM; CaCl2, 1.6 mM; Na2HPO4, 1.2 mM; morpholinopropanesulfonic acid, 2.0 mM (adjusted to pH 7.4 at either 0 or 37°C, as appropriate); Na2 ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA; to chelate trace heavy metals), 0.02; and dextrose, 5.6 mM. High purity (17MΩ) water was used throughout. For studies using gadolinium (Gd3+), phosphate and EDTA were not included in the PSS to avoid, respectively, precipitation of Gd3+ phosphate and Gd3+ chelation. For clarity in the results section, PSS will be referred to as a “Ca2+-containing solution” while PSS with no CaCl2 and the addition of 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) to chelate Ca2+ as a “Ca2+-free solution.” Thin (~200 microns thick) longitudinal detrusor muscle strips ~3 mm wide and ~5 mm long at slack muscle length were separated from the underlying bladder urothelium using micro-dissection. Each muscle strip was incubated in aerated PSS at 37°C in a water-jacketed tissue bath (Radnotti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA) and secured by small clips to a micrometer for length adjustments and an electronic lever (model 300H, Aurora Scientific, http://www.aurorascientific.com/index.asp). The lever was used to induce step (5 ms) and ramp (50 and 500 ms) muscle length changes (stretches), and to record isometric contractions.

2.2. Contraction of isolated detrusor strips

Isometric contractions were measured as described previously (Speich et al., 2005). Voltage signals were digitized (model DIO-DAS16, ComputerBoards, Mansfield, MA), visualized on a computer screen as force (g), and stored for analyses. All data analyses were performed using a multi-channel data integration program (DASYLab, TasyTec USA, Amherst, NH). Tissues were equilibrated for a minimum of 30 minutes suspended without tension between micrometer and lever. Tissues were then stretched to their optimum length for muscle contraction (Lo) using an abbreviated length-force determination (Uvelius, 1976). The optimum force for muscle contraction (Fo) produced by 110 mM KCl at Lo was obtained for each tissue. To reduce tissue-to-tissue variability, subsequent contractions were reported as normalized to Fo (F/Fo), or as the peak quick-stretch response (PQSR, Fig 1). To quantify peak and tonic forces produced by a quick-stretch in the presence and absence of a low concentration of carbachol (data presented in Fig 5), peak and tonic force values were obtained by subtracting the response produced in the Ca2+-free solution from that produced in the Ca2+-containing solution.

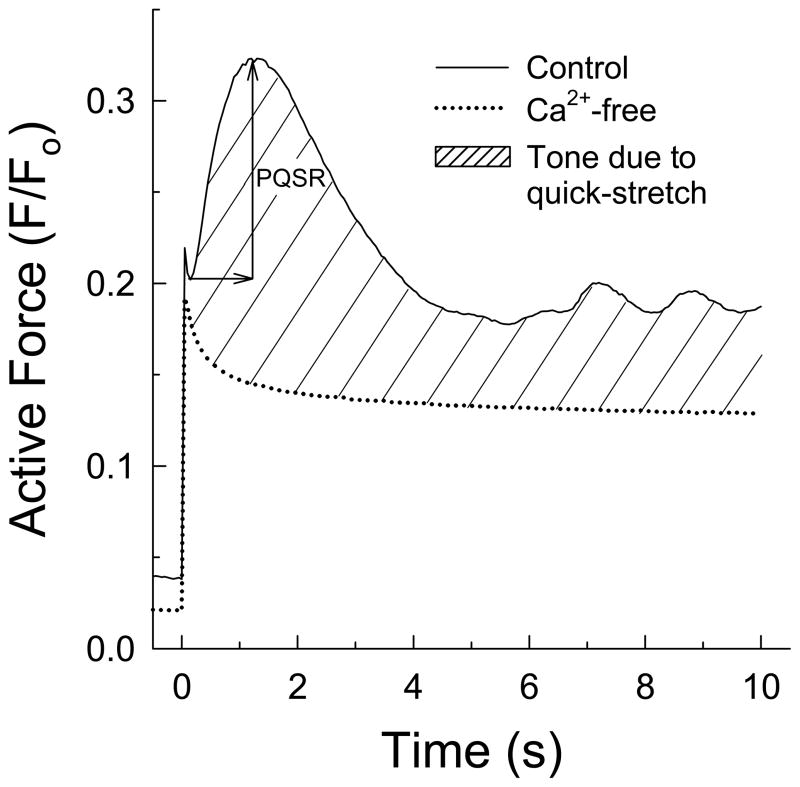

Figure 1.

Example of the force response produced upon a rapid (5 ms) imposed length-step equal to 15% of the optimum muscle length (Lo) in detrusor strips incubated in a Ca2+-free solution (dotted line) and in a Ca2+-containing solution (solid line). Myogenic tone is the force response produced by tissues in the Ca2+-containing solution (hatched area). The peak quick-stretch response (PQSR) was defined as the difference between maximum myogenic force produced above the minimum force attained, on average, 0.13 ms after the stretch.

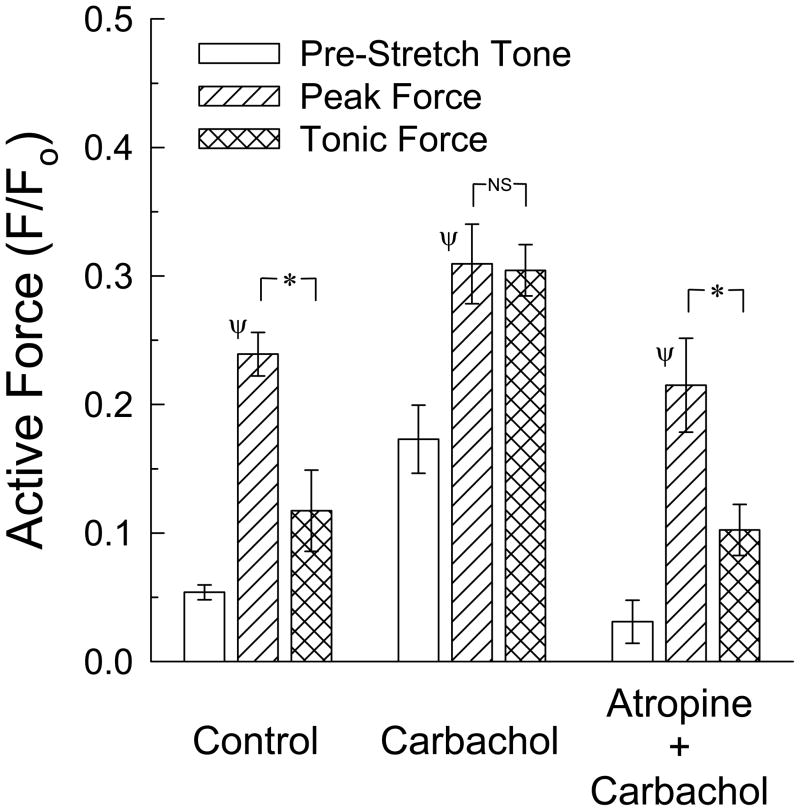

Figure 5.

Effect of weak stimulation of muscarinic receptors on the peak and tonic myogenic force. At a concentration that produced a weak (~10%) contraction, carbachol converted myogenic contraction induced by a 5 ms quick-stretch of 15% Lo from a transient response to a sustained response (tonic force was not different than peak force). Atropine (1 μM) abolished the ability of quick-stretch to induce a strong tonic myogenic response. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3. * P<0.05 comparing peak and tonic forces, Ψ P<0.05 compared to pre-stretch tone.

2.3. Applied length changes and resulting force responses

In most experiments, tissues secured to muscle clips were quickly (5 ms) stretched (quick-stretch) from Lo to a length 15% greater than Lo, held at this new length for 10 s, then released back to Lo. In one set of experiments, tissues were stretched more slowly (ramp-stretches of 50 and 500 ms), and in another set of experiments, the amplitude of the PQSR was measured in response to quick-stretches of three different lengths, 5%, 10% and 15% of Lo. Tissues that were quick-stretched responded with an immediate increase in force followed by a rapid decline in force characteristic of viscoelastic materials (stress-relaxation; (Fung, 1993)). In a Ca2+-free solution, stress-relaxation continued towards a steady-state force (Fig 1, dotted line), but in a Ca2+-containing solution, following a short latency period of 0.13 ± 0.01 s (n=5), tissues produced a strong, phasic contraction that peaked within 1.48 ± 0.17 s before declining to a weaker tonic contraction (Fig 1, solid line). Stress-relaxation is caused, in part, by frictional slippage due to breaking of non-covalent bonds. The rapid reversal of stress-relaxation by tissues exposed to a Ca2+-containing solution suggests that rapid stretch activated crossbridges and force development to offset the viscous fall in force. The degree of force produced in the Ca2+-containing solution minus that produced in the Ca2+-free solution represented active muscle tone (Fig 1, cross-hatched area). To quantify the strong, phasic, contractile component, the PQSR was defined as the maximum myogenic tone produced above the minimum force attained immediately after the quick-stretch latency period (Fig 1). As such, the PQSR underestimated the actual strength of active force produced upon muscle-stretch, but provided a reliable method to measure and compare the transient myogenic responses under different experimental conditions.

2.4. Myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation

The degree of MLC phosphorylation was measured as described previously (Jezior et al., 2001). Tissues were quick-frozen in an acetone-dry ice slurry, slowly warmed to room temperature, dried, weighed and homogenized on ice in 8M urea, 2% Triton X-100 and 20 mM dithiothreitol. Isoelectric variants of the 20 kDa MLCs were separated by 2-D (isoelectric focusing/sodium dodecyl sulfate) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Western blot onto Immobilon-P membranes ((Millipore; Bedford, MA), visualized by colloidal gold stain, and the relative amounts of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated MLCs were quantified by digital image analysis.

2.5. Myosin phosphatase targeting subunit (MYPT1) phosphorylation

The degree of MYPT1 site-specific phosphorylation was measured as described previously (Porter et al., 2006). Detrusor strips were quick-frozen in an acetone-dry ice slurry, thawed, homogenized in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% glycerol, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 20 mg/ml leupeptin, 2 mg/ml aprotinin, and 20 mg/ml (4-amidino-phenyl)-methanesulfonyl fluoride, heated 10 min at 100°C, clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min, and stored at −70°C. Thawed homogenates were assayed for protein concentration and proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 12% polyacrylamide gels (12 mg of protein per well) followed by Western blotting onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore; Bedford, MA). Threonine-853 phosphorylated MYPT1 (MYPT1-p[Thr853]) was identified using a phospho-selective antibody (anti-MYPT-p[Thr853] primary antibody, BD Biosiences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and detected using an horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). Quantification of visualized bands was obtained by digital image analysis software. To compensate for gel-to-gel variabilities in efficiencies of Western blotting, antibody labeling, enhanced chemiluminescence reaction, and film development, band intensities were reported as the degree of change from the Ca2+-free basal value. Use of MYPT1 primary antibody (BD Biosiences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) revealed that protein-loading was consistently uniform across all lanes of the gel (see Fig 9B).

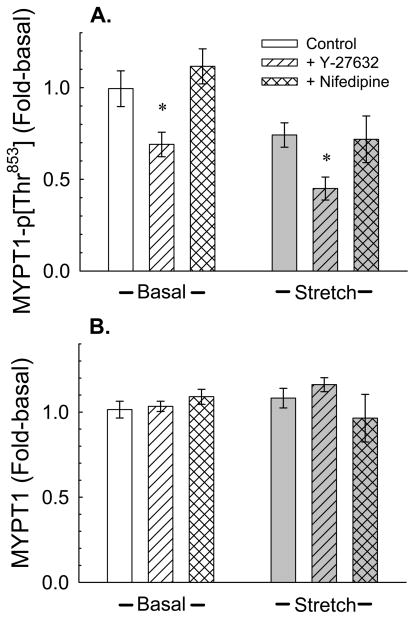

Figure 9.

Effect of Y-27632 and nifedipine (1 μM) on the degree of myosin phosphatase targeting subunit (MYPT) phosphorylation at threonine 853 (Thr853) under basal conditions and ~ 1sec after initiation of a quick-stretch. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–6. * P<0.05 compared to respective control values.

2.6. Drugs

Atropine, Gd3+, HA-1077 (1-(5-Isoquinolinesulfonyl)-1H-hexahydro-1,4-diazepine dihydrochloride) and Y-27632 (trans-4-[(1R)-1-Aminoethyl]-N-4-pyridinylcyclohexanecarboxamide dihydrochloride) were made as stock solutions in distilled water. Nifedipine was dissolved in ethanol, which was added to tissue baths at a final concentration of 0.01%. LOE-908 (3,4-Dihydro-6,7-dimethoxy-a-phenyl-N,N-bis[2-(2,3,4-tri methoxyphenyl)ethyl]-1-isoquinolineacetamide hydrochloride), GF-109203X (2-[1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)indol-3-yl]-3-(indol-3-yl) maleimide), cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and 2-APB (2,2-diphenyl-1,3,2-oxaza-borolidine) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, which was added at a final concentration of 0.1%. At these percentages, neither vehicle affected the myogenic response. Gd3+ was added to a phosphate- and EDTA-free physiological salt solution. LOE-908 was a kind gift from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, Connecticut. Y-27632 and CPA were from Calbiochem, 2-APB was from Cayman Chemical and GF-109203X was from Alexis Corporation. All other drugs were from Sigma Chemical Corp.

2.7. Statistics

Analysis of variance and the Student-Newman-Keuls test, or the t test, was used where appropriate to determine significance, and the Null hypothesis was rejected at P<0.05. The population sample size (n value) refers to the number of bladders, not the number of tissues.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the myogenic response in rabbit detrusor

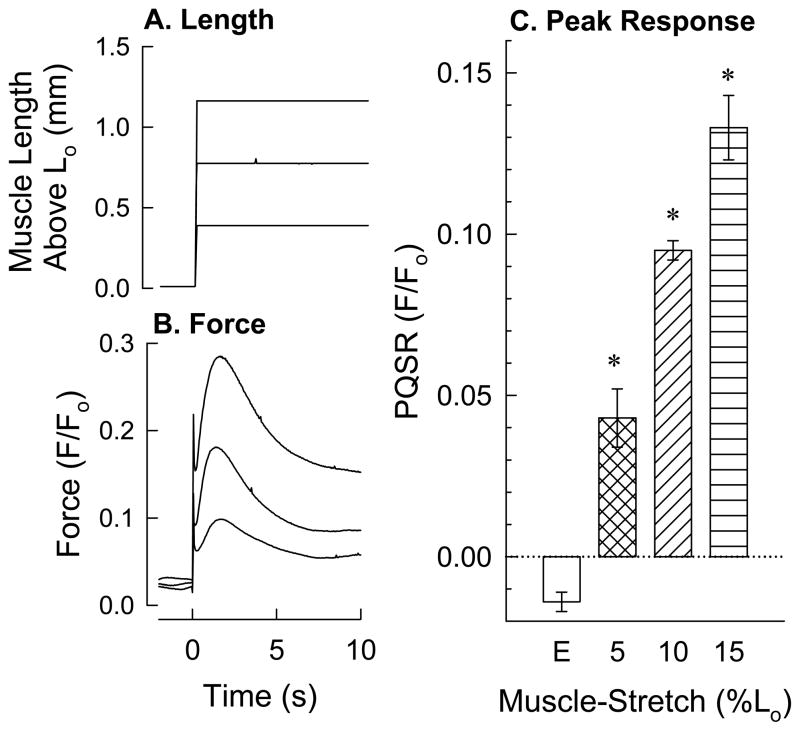

To determine whether the degree of myogenic contraction was dependent on the degree of stretch, tissues were subjected to quick-stretches of 5, 10 and 15% of Lo (Fig 2A), held at each new muscle length for 10 s to permit a myogenic contraction to occur, and the resulting PQSR (see “Methods” and Fig 1) values were recorded (Fig 2B). The PQSR produced by each length-step occurred ~1.5 s after application of the quick-stretch, and the degree of PQSR was dependent on the degree of length change (Fig 2C). Even the smallest length-step of 5% Lo produced a significant PQSR (Fig 2C, “5”) when compared to the level of force produced in tissues incubated in a Ca2+-free solution (Fig 2C, “E”).

Figure 2.

Effect of the degree of muscle stretch on the peak quick-stretch response (PQSR). Each tissue was quick (5 ms)-stretched by amounts equaling 5, 10 and 15% of Lo and held at the new muscle length for 10 s, permitting the development of myogenic contraction. An example of the length perturbation for three muscle strips is shown in panel A (upstroke of length-step lasted 5 ms, duration of length-step lasted 10 s), and the corresponding force response for each length-step is shown in panel B. Summary data is shown in panel C. PQSR measured for stretches in a Ca2+-containi ng solution (hatched bars) were compared to the force response produced in a Ca2+-free solution (open bar). Data in (C) are mean ± S.E.M., n = 5, * P<0.05 compared to “E”.

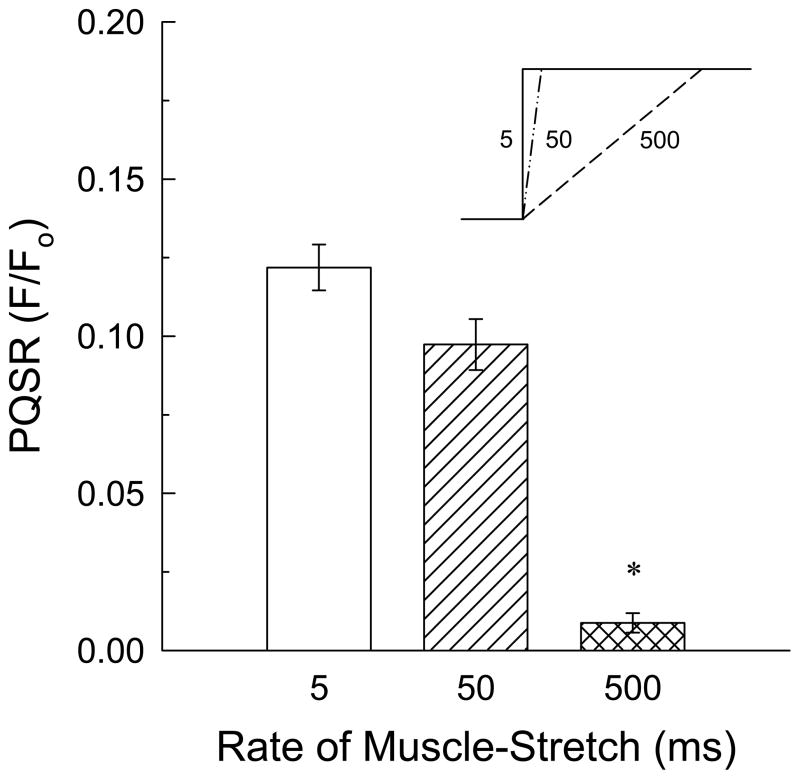

A 10-fold slower increase in length (50 ms ramp-stretch) still produced a strong PQSR that was not different than that produced by a 5 ms quick-stretch (Fig 3). However, a 100-fold slower ramp-stretch (500 ms) produced only a very weak PQSR (Fig 3). In all remaining studies, a 15%, 5 ms, quick-stretch was applied to produce a myogenic response.

Figure 3.

Effect of the rate of muscle stretch on peak quick-stretch response (PQSR) amplitude. Tissues were subjected to stretches equaling 15% Lo at 5, 50 and 500 ms (insert shows time on the x-axis and muscle length on the y-axis), and the resulting PQSR was recorded. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–5, * P<0.05 compared to 5 and 50 ms.

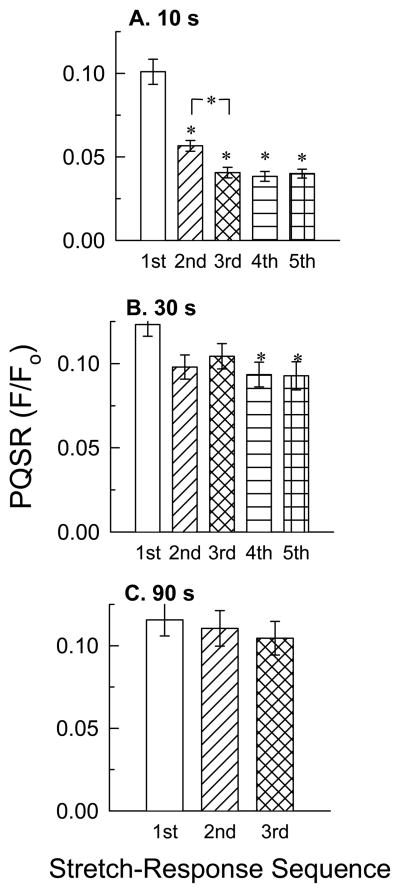

Sequential quick-stretches were applied and the amplitude of each resulting PQSR was measured to determine whether a refractory period exists for development of myogenic tone. The amplitude of the PQSR was reduced by half when two length-steps lasting 10 s each were applied 10 s apart (Fig 4A, “1st” versus “2nd”). A 3rd quick-stretch applied 10 s after the 2nd quick-stretch further reduced the PQSR (Fig 4A, “2nd” versus “3rd”), but no further reduction in PQSR amplitude occurred during the 4th and 5th quick-stretches (Fig 4A). A small reduction in the mean strength of the PQSR occurred when quick-stretches lasting 10 s each were applied 30 s apart. This reduction was significant only after application of the 4th and 5th quick-stretch (Fig 4B). A significant reduction in PQSR amplitude was not induced when 3 quick-stretches lasting 10 s each were applied sequentially 90 s apart (Fig 4C). This was likewise true when 4 quick-stretches were applied sequentially 300 s apart (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Identification of a refractory period for the peak quick-stretch response (PQSR). Tissues were quick (5 ms)-stretched by amounts equaling 15% of Lo and maintained at the new length for 10 s to permit development of a myogenic contraction before each muscle was returned to Lo. This sequence was repeated 5 times every 10 (A) or 30 (B) s, or 3 times every 90 (C) s. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 8, * P<0.05 compared to the 1st response.

The muscarinic receptor agonist, carbachol, at a low concentration (3 × 10−8M) that alone produced a weak contraction ~10% above basal tone (Fig 5, compare Carbachol open bar to Control open bar) converted the myogenic response from one characterized by a strong phasic and weak tonic contraction (Fig 5, Control hatched and cross-hatched bars) to one characterized by a strong, sustained response (Fig 5, Carbachol hatched and cross-hatched bars). Atropine (1 μM) abolished both pre-stretch weak contraction produced by carbachol and the sustained phase of the myogenic response produced in response to stretch in the presence of carbachol (Fig 5, Atropine + Carbachol).

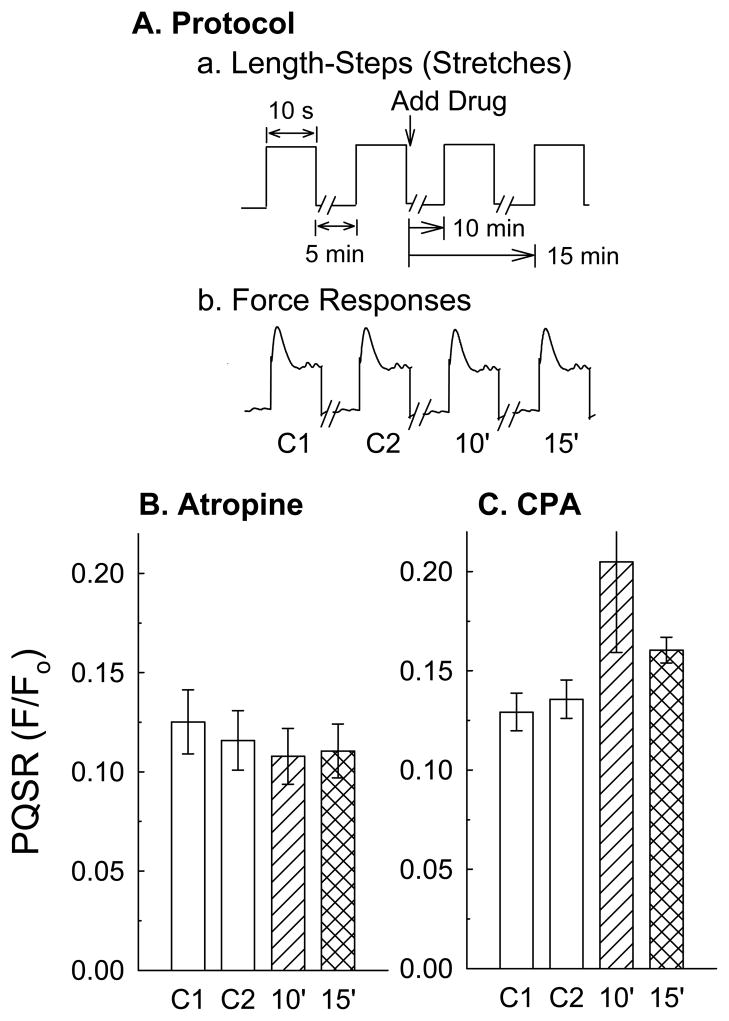

3.2. Effect on PQSR amplitude of atropine, CPA, inhibitors of Ca2+ channels, and inhibitors of ROCK and PKC

The effects of selective receptor, ion channel and enzyme inhibitors on PQSR were examined using the protocol shown diagrammatically in Fig 6A. Results from data shown in Fig 5 suggest that atropine did not affect the PQSR. To more definitively determine whether the PQSR was not the result of the action of acetylcholine released from cholinergic neurons on DSM, 1 μM atropine was added to tissues 10 and 15 minutes prior to quick-stretches to block DSM muscarinic receptors. Compared to control (Fig 6B, C1 and C2), atropine did not reduce the strength of the PQSR (Fig 6B, 10′ (= 10 minutes) and 15′ (= 15 minutes)). This concentration of atropine completely inhibited contractions produced by 10 μM bethanechol, a concentration of muscarinic receptor agonist that produces nearly a maximum rabbit DSM contraction (Shenfeld et al., 1998). To determine whether the PQSR could be abolished by sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum pump inhibition, tissues incubated with 10 μM CPA were subjected to the quick-stretch protocol shown in Fig 6A. CPA did not prevent the development of a strong PQSR (Fig 6C). In fact, the mean value of the PQSR in the presence of CPA was elevated compared to control, although this apparent increase was not significant. These data do not eliminate a role for the sarcoplasmic reticulum in causing a myogenic contraction, but suggest that Ca2+ entry, possibly in conjunction with sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release, is a required signaling event linking the mechanical stimulus (quick-stretch) with the resulting contraction (PQSR).

Figure 6.

Protocol for the effect of selective drugs on the peak quick-stretch response (PQSR) is shown in panel A (a. imposed length change, b. resulting force change), and the effects of the cholinergic antagonist, atropine (1 μM), and the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum pump inhibitor, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μM), on PQSR are shown in, respectively, panels B and C. Tissues were quick (5 ms)-stretched by amounts equaling 15% of Lo and maintained at the new length for 10 s to permit development of a myogenic contraction before each muscle was returned to Lo. This was repeated again 5 min later and the PQSRs to these 1st and 2nd quick-stretches were labeled control 1 (C1) and control 2 (C2), respectively. Atropine was added and 10 min (10′) and 15 min (15′) later tissues were subjected to 3rd and 4th quick-stretches, respectively. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–6.

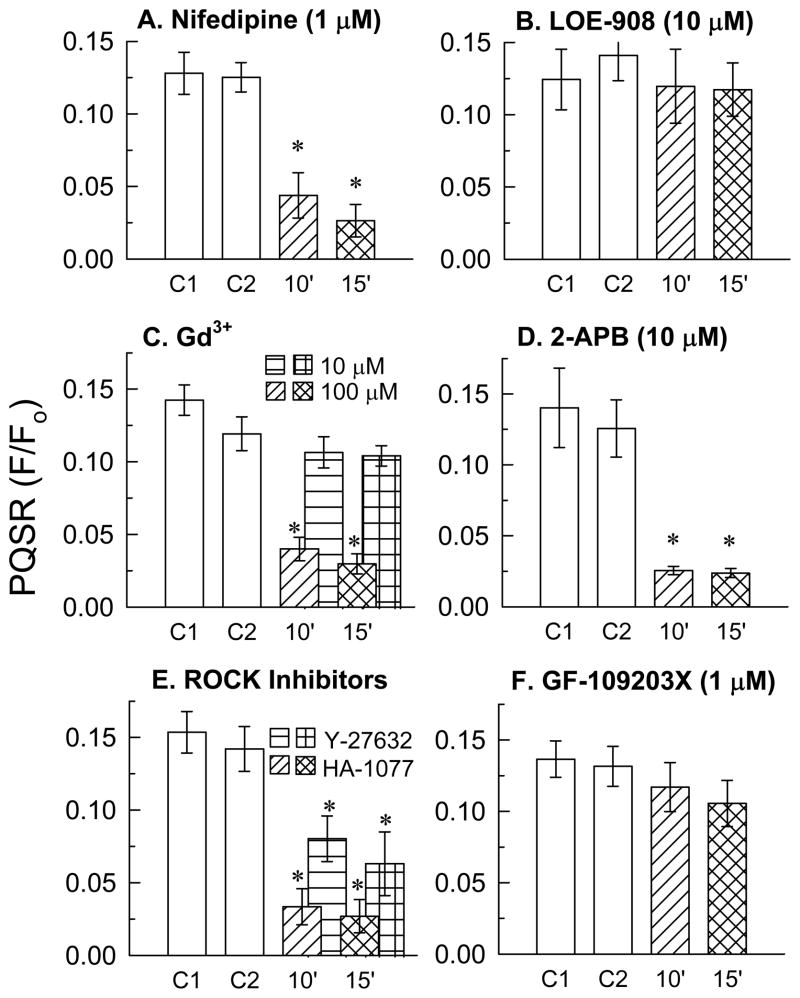

L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCCs) and non-selective cation channels (NSCCs) may participate in stretch-activated Ca2+ influx in vascular smooth muscle cells (Davis and Hill, 1999). We therefore tested the hypothesis that these channel types also participate in quick-stretch-induced contraction of DSM by employing nifedipine and LOE-908, blockers of, respectively, VOCCs (McDonald et al., 1994) and NSCCs (Krautwurst et al., 1994). Nifedipine, at a concentration that inhibits KCl-induced contractions (1 μM), nearly abolished the PQSR (Fig 7A). Notably, 10 μM LOE-908, a concentration of NSCC blocker that strongly inhibits receptor-stimulated contractions in vascular smooth muscle (Krautwurst et al., 1994) and reduces by half the maximum contraction produced in detrusor by muscarinic receptor activation (Jezior et al., 2001), did not reduce the amplitude of the PQSR (Fig 7B). Gd3+, a trivalent cation that concentration-dependently inhibits stretch-activated cation channels, certain transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, and VOCCs (Hamill and McBride, 1996; Lievremont et al., 2005; Morita et al., 2007; Yang and Sachs, 1989; Zhu et al., 1998), had no effect at 10 μM, but greatly reduced the amplitude of the PQSR at 100 μM (Fig 7C). Because 10 μM Gd3+ inhibits TRP channels responsible for store-operated cation channel activity, whereas 100 μM Gd3+ is required to inhibit TRPC3/6/7 channels responsible for other forms of Ca2+ entry (Lievremont et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 1998), we also examined the effect of 2-APB at a concentration known to selectively inhibit TRPC3/6/7 channels (Lievremont et al., 2005), but to not inhibit VOCCs (Luo et al., 2001; Poteser et al., 2003). 2-APB at 10 μM, like nifedipine and 100 μM Gd3+, strongly inhibited PQSR (Fig 7D).

Figure 7.

Effects on the PQSR of the selective L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channel (VOCC) blocker, nifedipine (A), the non-selective cation channel blocker, LOE-908 (B), the cation channel blocker, Gd3+ (C), the TRP channel blocker, 2-APB (D), the ROCK blockers Y-27632 (1 μM) and HA-1077 (10 μM, E), and the inhibitor of conventional and novel isoforms of PKC, GF-109203X (F). Drugs were added immediately after recovery from the 2nd quick-stretch, as shown in panel A of Fig 6. Responses to the 1st and 2nd quick-stretches were labeled control 1 (C1) and control 2 (C2), respectively, and to the 3rd and 4th quick-stretches after addition of drug were labeled 10 min (10′) and 15 min (15′), respectively. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–6. * P<0.05 compared to C1.

Although G protein-coupled receptor stimulation and KCl are stimuli that cause activation of ROCK (Ratz et al., 2005; Somlyo and Somlyo, 2000), whether mechanical stretch of DSM also does so remains to be determined. In the present study, both Y-27632 (Fig 7E) and HA-1077 (Fig 7E), at concentrations that produce relatively selective inhibition of ROCK activity (Davies et al., 2000), caused a significant reduction in the amplitude of the PQSR.

Certain PKC isotypes may also participate in regulation of smooth muscle contraction through inhibition of MLC phosphatase (Eto et al., 2001). We used GF-109203X at a concentration that inhibits conventional and novel isotypes of PKC (PKCc,n), (Eto et al., 2001; Martiny-Baron et al., 1993), to test the hypothesis that PKC may play a role in regulation of stretch-activated detrusor contraction. At 1 μM, GF-109203X did not reduce the amplitude of the PQSR (Fig 7F).

3.3. Effect of Y-27632 on basal and quick-stretch-induced MLC phosphorylation

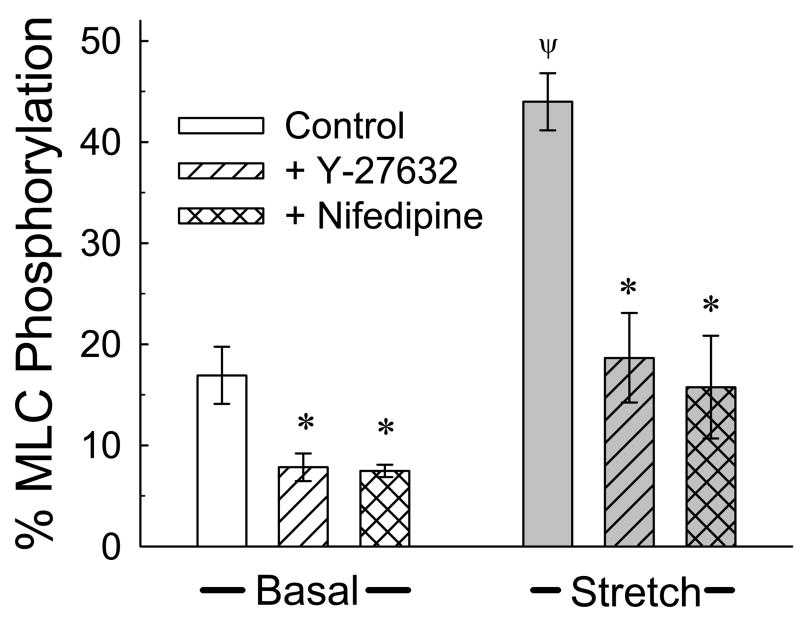

To determine whether quick-stretch causes increases in MLC phosphorylation, and whether inhibition of the PQSR by Y-27632 corresponded with reductions in the degree of MLC phosphorylation, tissues were quick-stretched, frozen ~1 s later, and processed to measure MLC phosphorylation. In agreement with our previous report (Ratz and Miner, 2003), basal MLC phosphorylation was ~15% and was inhibited by 1 μM Y-27632 (Fig 8, “Basal”). Quick-stretch produced a strong increase in MLC phosphorylation (Fig 8, “Stretch”) that was also inhibited by Y-27632 (Fig 8, hatched bar). Like Y-27632, the Ca2+ channel blocker, nifedipine (1 μM) inhibited both basal and quick-stretch-stimulated increases in the degree of MLC phosphorylation (Fig 8, cross-hatched bars).

Figure 8.

Quick-stretch induced a large increase above the basal level in myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation at ~ 1 s (Ψ P < 0.05 compared to control basal). Y-27632 and nifedipine (1 μM) inhibited the degree of MLC phosphorylation produced basally and at 1 s of muscle quick-stretch. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–8. * P<0.05 compared to respective control values.

3.4. Effects of Y-27632 and nifedipine on basal and quick-stretch-induced MYPT1 site-specific phosphorylation at threonine 853 (MYPT-p[Thr853])

ROCK can regulate myosin phosphatase activity by phosphorylating MYPT1 at threonine 853 (Kitazawa et al., 2003; Velasco et al., 2002). We therefore measured the relative degree of MYPT-p[Thr853] in resting (basal) detrusor and at ~1 s after tissues had been quick-stretched. Quick-stretch did not increase the degree of MYPT-p[Thr853] compared to the basal level (Fig 9A), and although the mean value was reduced, this apparent decrease was not significant. The amounts of MYPT-p[Thr853] produced both basally and during the 1st second of a quick-stretch were reduced by ~30% by 1 μM Y-27632, but not by 1 μM nifedipine (Fig 9A). No differences in levels of total MYPT were identified (Fig 9B).

In summary, the strong increase in MLC phosphorylation and transient contraction (PQSR) induced by quick-stretch were both inhibited by Y-27632, but quick-stretch did not cause phosphorylation of the ROCK substrate, MYPT1, suggesting that quick-stretch did not activate ROCK above the basal level. These data together support the hypothesis that ROCK was constitutively active, and that this constitutive activity was required for full development of the PQSR.

4. Discussion

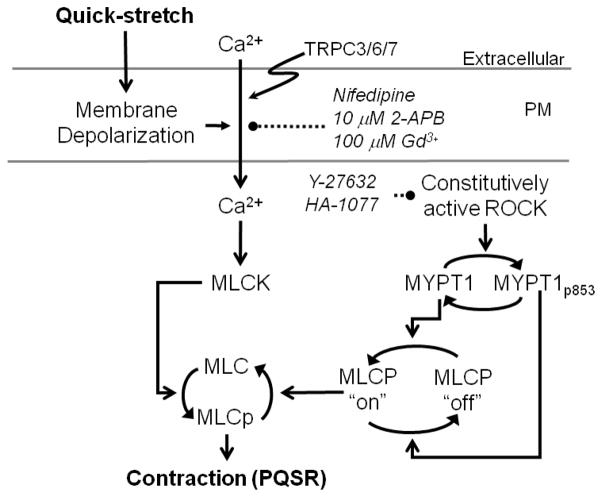

This study provides data supporting the hypothesis that the contractile response produced upon quick-stretch of DSM strips (PQSR) was caused by activation of Ca2+ channels resulting in increases in cytosolic Ca2+ levels in the presence of constitutively active ROCK, an enzyme known to enhance the degree of MLC phosphorylation by inhibition of MLC phosphatase activity (Hartshorne et al., 1998). The significance of this finding is two-fold. First, in addition to playing a principal role in regulation of stimulus-induced Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contractile protein activation (Ratz et al., 2005; Somlyo and Somlyo, 2000), results from the present study support the novel hypothesis that ROCK appears also to play a prominent permissive role in DSM contractions, a result supported by our previous finding that basal rhythmic tone and MLC phosphorylation are also strongly attenuated by ROCK inhibition in strips of rabbit detrusor (Ratz and Miner, 2003). Second, there is strong evidence that the most proximal, or upstream linkage between mechanical quick-stretch and initiation of cell signaling events in DSM is activation of ryanodine receptors and release of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ causing Ca2+ sparks (Ji et al., 2002). Our data reveal that the downstream events must include stimulated Ca2+ entry along with constitutive ROCK activity for production of a full stretch-induced contraction. Thus, we propose that stimulated Ca2+ entry is necessary and links mechanical quick-stretch with contraction. In this working model (Fig 10), stimulated Ca2+ entry alone is necessary but insufficient to generate a full myogenic contraction, because constitutive ROCK activity is also required to maintain MLC phosphatase in an inactive conformation, permitting a strong increase in force. Moreover, based on a comparative pharmacological approach, TRPC3/6/7 and L-type VOCC channels appear to have played the primary role in the Ca2+ entry linking quick-stretch with contraction.

Figure 10.

Working model of cell signaling systems operating during quick-stretch-induced myogenic contraction. Development of a full quick-stretch-induced contraction required constitutive, not stimulated ROCK activity, and quick-stretch-stimulated activation of Ca2+ entry that was sensitive to blockade by nifedipine, low concentrations of 2-APB, and high concentrations of Gd3+. Extracellular = extracellular space; PM = plasma membrane.; MLC = myosin light chain; MLCK = MLC kinase; MLCP = MLC phosphatase; MYPT1 = myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1; TRPC3/6/7 = transient receptor potential canonical channel isoform 3, 6 or 7.

The most significant recent advance coupling stimulus-dependent Ca2+ channel physiology such as store- and receptor-operated Ca2+ entry with Ca2+ channel type was the discovery of TRP channels, a family of over 50 structurally related proteins displaying a diverse stimulation profile (Beech, 2005). Thus far, the only organic channel blocker known to be selective for certain TRP channels is 2-APB (Lievremont et al., 2005). 2-APB displays an IC50 of 20 μM for TRPC5 channels (Xu et al., 2005), and at 10 μM, 2-APB inhibits TRPC3/6/7 by more than 50% while displaying no inhibition of inositol trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ release (Lievremont et al., 2005). 2-APB does not inhibit VOCCs (Luo et al., 2001; Poteser et al., 2003) ryanodine receptors (Wu et al., 2000), arachidonic acid-activated cation channels (Luo et al., 2001), S-nitrosylation-activated channels (van Rossum et al., 2000), Ca2+-activated Cl− entry channels (Wu et al., 2000), or stretch-activated cation channels thought to be dependent on TRPM4-like non-selective cation channels (Sarkozi et al., 2005). Our data showed that the PQSR in DSM was nearly abolished by 10 μM 2-APB. Because TRPC3/6/7 channels are expressed by smooth muscle (Dietrich et al., 2005), these data suggest that TRP3/6/7 channels may have participated in the Ca2+ entry responsible for stretch-activated contraction in rabbit DSM. This conclusion supports the proposal that TRPC3/6/7 can serve not only as a receptor-operated and store-operated channel, but also as a mechano-sensitive channel (Beech, 2005). However, a recent study (Bai et al., 2006) reports that at the concentration used in the present study, 2-APB can effectively inhibit certain connexin isoforms and gap junction formation. Thus, our data cannot rule out the possibility that quick-stretch of rabbit DSM strips enhanced gap junction formation, permitting cell-to-cell coupling and a strong myogenic contraction.

TRPC3/6/7-dependent Ca2+ entry that is not dependent on sarcoplasmic reticulum store depletion is inhibited by 100 μM, but not 10 μM Gd3+ (Lievremont et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 1998). Thus, our data showing that 100 μM, but not 10 μM Gd3+ inhibited the PQSR supports our contention that a TRPC3/6/7 channel was activated downstream from mechanical stretch. Moreover, because Gd3+ inhibits ryanodine receptor Ca2+ channel activity with an IC50 of 5–6 μM (Sarkozi et al., 2005), these data suggest that the quick-stretch-induced myogenic contraction of rabbit DSM in the present study was not dependent on ryanodine receptor activation.

L-type VOCCs are sensitive not only to membrane depolarization, but also to mechanical stretch (Langton, 1993), and our finding that nifedipine strongly inhibited the PQSR suggests that VOCCs also played a role in stretch-induced contraction in DSM. However, several studies indicate that certain TRP-dependent channels may be as sensitive to inhibition by nifedipine and related compounds as are L-type VOCCs (Curtis and Scholfield, 2001; Krutetskaia et al., 1997; Willmott et al., 1996; Zhu et al., 1998), which is supported by evidence for sequence similarity between TRP channels and the α1 subunit of L-type VOCCs (Phillips et al., 1992). For example, the VOCC blocker, verapamil, inhibits TRPC3 channels with an IC50 of 4 μM (Zhu et al., 1998). Also, in the present study, the PQSR was not inhibited by a low concentration (10 μM) of Gd3+, which has been shown to effectively inhibit VOCCs (Hamill and McBride, 1996; Wu and Davis, 2001). Thus, an alternative conclusion is that VOCCs did not contribute to the PQSR, and instead, that TRPC3/6/7 channels sensitive to nifedipine were responsible for stretch-activated Ca2+ entry leading to the PQSR in rabbit DSM. LOE-908 effectively inhibits not only basal tone but also muscarinic receptor-induced contraction in rabbit detrusor (Jezior et al., 2001), indicating that NSCCs play an essential role in these responses. Thus, stretch-activated myogenic contraction is distinct from basal tone and muscarinic receptor-induced contractions because LOE-908-sensitive NSCCs did not appear to play a role in myogenic contraction. These data, along with the finding that atropine did not suppress the PQSR, indicate that the myogenic response produced by quick-stretch in rabbit DSM did not involve muscarinic receptor activation.

The muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine, did not inhibit the ability of quick-stretch to cause a contraction. These data can be taken as evidence that the isolated longitudinal bundles of DSM in the micro-dissected bladder strips in our preparation did not contain urothelium and suburothelial tissues, which respond to stretch by releasing acetylcholine causing bladder contraction (Yoshida et al., 2006).

Both ROCK and PKC have been implicated in regulation of vascular myogenic tone (Dubroca et al., 2005; Yeon et al., 2002). ROCK, PKCα and PKCδ can enhance Ca2+-activated contraction by inhibition of MLC phosphatase, thus causing Ca2+ sensitization, an increase in the degree of force for a given increase in [Ca2+]i. Y-27632 is highly selective for inhibition of ROCK compared to MLC kinase, conventional PKC isotypes such as PKCα, and several other enzymes (Davies et al., 2000). However, Y-27632 also inhibits PKCδ, a novel PKC isotype (Eto et al., 2001). Thus, the use of Y-27632 alone is insufficient to distinguish between ROCK and PKCδ in causing smooth muscle contraction by enhancing Ca2+ sensitivity. For this reason, the use of GF-109203X and Y-27632 have been used to discriminate between ROCK and PKCδ activities (1 μM Y-27632 inhibits PKCδ and ROCK, but 1 μM GF-109203X inhibits PKCδ, not ROCK (Eto et al., 2001; Martiny-Baron et al., 1993)). In the present study, 1 μM GF-109203X did not reduce the amplitude of the PQSR, while 1μM Y-27632 reduced the amplitude by more than 50%. These data suggest that ROCK, not PKCδ, was involved in the stretch-activated myogenic contraction. Moreover, 10 μM HA-1077 nearly abolished the PQSR, and HA-1077 is a potent inhibitor of ROCK compared to MLC kinase and PKCα (Sward et al., 2000). Because 1 μM GF-109203X inhibits PKCα (Martiny-Baron et al., 1993), this enzyme may also be ruled out as participating in the stretch-induced myogenic response in rabbit DSM.

In support of our model (see Fig 10) that stretch stimulated Ca2+ entry to cause activation of MLC kinase (MLCK), we found that stretch increased the degree of MLC phosphorylation above the basal level of ~15% by ~3-fold to ~45%, and that nifedipine abolished this increase. Stretch did not cause an increase above the basal level in the ROCK substrate responsible for causing Ca2+ sensitization, MYPT-p[Thr853]. However, basal MYPT-p[Thr853] was reduced by ~40% by the ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632, and not by nifedipine. Y-27632 likewise reduced basal MLC phosphorylation to under 10%. Together, these data support the hypothesis that ROCK was constitutively active in DSM, and that the constitutive activity contributed to the contraction produced upon quick-stretch, but that quick-stretch did not further activate ROCK. Given the recent report that a threshold level of MLC phosphorylation of ~15% must be attained before contraction can occur in smooth muscle (Rembold et al., 2004), these data suggest that constitutive ROCK activity is essential to permit a rapid increase in MLC phosphorylation above the threshold level causing rapid contraction upon muscle stimulation.

While similar, myogenic tone of the detrusor and vasculature are distinct in at least two ways. First, both ROCK and PKC regulate myogenic tone of basilar artery (Yeon et al., 2002), whereas the present study indicates that ROCK plays the principal role in detrusor. Second, myogenic tone in the vasculature is sustained (Davis and Hill, 1999), while in detrusor, it is transient. Interestingly, in the present study, weak stimulation of muscarinic receptors known to activate PKC converted the transient myogenic contraction to a sustained contraction.

The amplitude of the myogenic contraction was dependent on the amplitude of the length-step (see Fig 2). These data support the hypothesis that the role of the myogenic contraction is to provide high fidelity mechanical coupling of DSM cells acting as a unit. With such coupling, the degree of length change imposed on nearby DSM cells by, for example, rapidly contracting innervated DSM cells, would be proportional to the numbers of innervated cells activated, which would in turn translate to a proportional strength of myogenic contraction. Although the amplitude of the myogenic contraction was dependent on the amplitude of the length-step, only fast (5 or 50 ms), not slow (500 ms) stretches produced a myogenic contraction. Thus, the stimulus for induction of a myogenic contraction appeared to be muscle force rather than muscle length (Fung, 1993). One or more steps in the signaling sequence required less than 90 s, but more than 30 s for full recovery, because the amplitude of the peak myogenic response was significantly reduced when stretches were repeated every 10 or 30 s, but not when stretches were repeated every 90 s. Ion channel recovery from inactivation is usually measured on the ms time scale, suggesting that the refractory period for the myogenic response may not have been due to inactive ion channels. Interestingly, Ca2+ sensitivity involving ROCK can be down-regulated for long periods (Ratz, 1995), suggesting that inactivation of ROCK or ROCK signaling systems may have been responsible for the myogenic response refractory period. Alternatively, the refractory period may reflect mechanical accommodation of the stretch sensor.

In summary, the present study supports an active role for Ca2+ entry and a permissive role for ROCK activity in the DSM contraction induced by muscle quick-stretch. Our data ruled out LOE-908-sensitive NSCCs from participating in myogenic contraction, but showed that a 2-APB- and nifedipine-sensitive, but 10 μM Gd3+-insensitive channel participates. The most likely channel consistent with this pharmacological profile is a TRPC3/6/7 cation channel. Moreover, this study showed that the amplitude of the detrusor myogenic response was dependent on the rate and degree of muscle stretch, displayed a relatively long (~30 s) refractory period, and was converted from a biphasic to a sustained contraction by weak stimulation of muscarinic receptors. Myogenic detrusor contraction may participate in the mechanical synchronization of contractions of multiple muscle cells permitting syncytial-like detrusor contraction (i.e., the rapid contraction of one cell would stretch an adjacent cell, causing membrane depolarization and contraction). As such, the detrusor myogenic response may represent a novel target for therapeutic agents designed to treat urological disorders such as overactive bladder.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK-59620 to PHR) and from the Edwin Beer Research Program in Urology and Urology-Related Fields of The New York Academy of Medicine (to JES).

Support: Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK59620)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersson S, Kronstrom A, Teien D. Wall mechanics of the rat bladder. I. Hydrodynamic studies in the time domain. Acta Physiol Scand. 1988;134:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1998.tb08518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artibani W. Diagnosis and significance of idiopathic overactive bladder. Urology. 1997;50:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai D, del Corsso C, Srinivas M, Spray DC. Block of specific gap junction channel subtypes by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1452–1458. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ. Emerging functions of 10 types of TRP cationic channel in vascular smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:597–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Muraki K, Flemming R. Non-selective cationic channels of smooth muscle and the mammalian homologues of Drosophila TRP. J Physiol. 2004;559:685–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Prosser CL. Response of smooth muscles to quick stretch; relation of stretch to conduction. Am J Physiol. 1960;198:921–925. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.198.5.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolsaet BLRA, Blaivas JG. No detrusor is stable. Neurourol Urodyn. 1985;4:259–261. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis TM, Scholfield CN. Nifedipine blocks Ca2+ store refilling through a pathway not involving L-type Ca2+ channels in rabbit arteriolar smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2001;532:609–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0609e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:387–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Kalwa H, Rost BR, Gudermann T. The diacylgylcerol-sensitive TRPC3/6/7 subfamily of cation channels: functional characterization and physiological relevance. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:72–80. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake MJ, Hedlund P, Harvey IJ, Pandita RK, Andersson KE, Gillespie JI. Partial outlet obstruction enhances modular autonomous activity in the isolated rat bladder. J Urol. 2003;170:276–279. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000069722.35137.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubroca C, You D, Levy BI, Loufrani L, Henrion D. Involvement of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in myogenic tone in the rabbit facial vein. Hypertension. 2005;45:974–979. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164582.63421.2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbadawi A. Pathology and pathophysiology of detrusor in incontinence. Urol Clin. 1995;22:499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto M, Kitazawa T, Yazawa M, Mukai H, Ono Y, Brautigan DL. Histamine-induced vasoconstriction involves phosphorylation of a specific inhibitor protein for myosin phosphatase by protein kinase C alpha and delta isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29072–29078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung YC. Biomechanics. 2. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JI. The autonomous bladder: a view of the origin of bladder overactivity and sensory urge. BJU Int. 2004;93:478–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JI, Harvey IJ, Drake MJ. Agonist- and nerve-induced phasic activity in the isolated whole bladder of the guinea pig: evidence for two types of bladder activity. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:343–357. doi: 10.1113/eph8802536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DWJ. The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel C, Wienhold D, Benken N, Eggersmann C, Thuroff JW. Definition of overactive bladder and epidemiology of urinary incontinence. Urology. 1997;50:4–14. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne DJ, Ito M, Erdodi F. Myosin light chain phosphatase: Subunit composition, interactions and regulation. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1998;19:325–341. doi: 10.1023/a:1005385302064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezior JR, Brady JD, Rosenstein DI, McCammon KA, Miner AS, Ratz PH. Dependency of detrusor contractions on calcium sensitization and calcium entry through LOE-908-sensitive channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:78–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Barsotti RJ, Feldman ME, Kotlikoff MI. Stretch-induced calcium release in smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:533–544. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PC. The myogenic response. In: David F, Bohr APS, Sparks Harvey V Jr, editors. Handbook of Physiology: The Cardiovascular System; Vascular Smooth Muscle. American Physiological Society; Bethesda: 1980. pp. 409–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder RB, Mundy AR. Pathophysiology of idiopathic detrusor instability and detrusor hyperreflexia. Br J Urol. 1987;60:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa T, Eto M, Woodsome TP, Khalequzzaman M. Phosphorylation of the myosin phosphatase targeting subunit and CPI-17 during Ca(2+) sensitization in rabbit smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2003;546:879–889. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautwurst D, Degtiar VE, Schultz G, Hescheler J. The isoquinoline derivative LOE 908 selectively blocks vasopressin-activated nonselective cation currents in A7r5 aortic smooth muscle cells. Naunyn-Schmiederbergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;349:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00169297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutetskaia ZI, Lebedev OE, Krutetskaia NI, Petrova TV. Organic and inorganic blockers of potential-dependent Ca2+ channels inhibit store-dependent entry of Ca2+ into rat peritoneal macrophages. Tsitologiia. 1997;39:1131–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagaud G, Gaudreault N, Moore ED, Van Breemen C, Laher I. Pressure-dependent myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries occurs independently of voltage-dependent activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2187–2195. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton PD. Calcium channel currents recorded from isolated myocytes of rat basilar artery are stretch sensitive. J Physiol. 1993;471:1–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievremont JP, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Mechanism of inhibition of TRPC cation channels by 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:758–762. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D, Broad LM, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Signaling pathways underlying muscarinic receptor-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in HEK293 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5613–5621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, Marme D, Schachtele C. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9194–9197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters JG, Neal DE, Gillespie JI. Contractions in human detrusor smooth muscle induced by hypo-osmolar solutions. J Urol. 1999;162:581–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TF, Pelzer S, Trautwein W, JPD Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:365–507. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Honda A, Inoue R, Ito Y, Abe K, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Membrane stretch-induced activation of a TRPM4-like nonselective cation channel in cerebral artery myocytes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;103:417–426. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0061332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AM, Bull A, Kelly LE. Identification of a Drosophila gene encoding a calmodulin-binding protein with homology to the trp phototransduction gene. Neuron. 1992;8:631–642. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Evans MC, Miner AS, Berg KM, Ward KR, Ratz PH. Convergence of Calcium Desensitizing Mechanisms Activated by Forskolin and Phenylephrine Pretreatment, But Not 8-bromo-cGMP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1552–1559. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00534.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteser M, Wakabayashi I, Rosker C, Teubl M, Schindl R, Soldatov NM, Romanin C, Groschner K. Crosstalk between voltage-independent Ca2+ channels and L-type Ca2+ channels in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells at elevated intracellular pH: evidence for functional coupling between L-type Ca2+ channels and a 2-APB-sensitive cation channel. Circ Res. 2003;92:888–896. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069216.80612.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratz PH. Receptor activation induces short-term modulation of arterial contractions: memory in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C417–C423. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.2.C417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratz PH, Berg KM, Urban NH, Miner AS. Regulation of smooth muscle calcium sensitivity: KCl as a calcium-sensitizing stimulus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C769–783. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratz PH, Miner AS. Length-dependent regulation of basal myosin phosphorylation and force in detrusor smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1063–R1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00596.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rembold CM, Wardle RL, Wingard CJ, Batts TW, Etter EF, Murphy RA. Cooperative attachment of cross bridges predicts regulation of smooth muscle force by myosin phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C594–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00082.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkozi S, Szegedi C, Lukacs B, Ronjat M, Jona I. Effect of gadolinium on the ryanodine receptor/sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release channel of skeletal muscle. Febs J. 2005;272:464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenfeld OZ, Morgan CW, Ratz PH. Bethanechol activates a post-receptor negative feedback mechanism in rabbit urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Urol. 1998;159:252–257. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction by G-proteins, Rho-kinase and protein phosphatase to smooth muscle and non-muscle myosin II. J Physiol. 2000;522.2:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speich JE, Borgsmiller L, Call C, Mohr R, Ratz PH. ROK-induced cross-link formation stiffens passive muscle: reversible strain-induced stress softening in rabbit detrusor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C12–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streng T, Hedlund P, Talo A, Andersson KE, Gillespie JI. Phasic non-micturition contractions in the bladder of the anaesthetized and awake rat. BJU Int. 2006;97:1094–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sward K, Dreja K, Susnjar M, Hellstrand P, Hartshorne DJ, Walsh MP. Inhibition of rho-associated kinase blocks agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization of myosin phosphorylation and force in guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 2000;522:33–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.0033m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvelius B. Isometric and isotonic length-tension relations and variations in longitudinal smooth muscle from rabbit urinary bladder. Acta Physiol Scand. 1976;97:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum DB, Patterson RL, Ma HT, Gill DL. Ca2+ entry mediated by store depletion, S-nitrosylation, and TRP3 channels. Comparison of coupling and function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28562–28568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco G, Armstrong C, Morrice N, Frame S, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of the regulatory subunit of smooth muscle protein phosphatase 1M at Thr850 induces its dissociation from myosin. FEBS Letters. 2002;527:101–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B, Chen Z, Zhang X, Feldman M, Dong XZ, Doran R, Zhao BL, Yin WX, Kotlikoff MI, Ji G. Nitric oxide mediates stretch-induced Ca2+ release via activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway in smooth muscle. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellner C, Isenberg G. Stretch effects on whole-cell currents of guinea-pig urinary bladder myocytes. J Physiol. 1994;480 (Pt 3):439–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmott NJ, Choudhury Q, Flower RJ. Functional importance of the dihydropyridine-sensitive, yet voltage-insensitive store-operated Ca2+ influx of U937 cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Kamimura N, Takeo T, Suga S, Wakui M, Maruyama T, Mikoshiba K. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate modulates kinetics of intracellular Ca(2+) signals mediated by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca(2+) stores in single pancreatic acinar cells of mouse. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1368–1374. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Davis MJ. Characterization of stretch-activated cation current in coronary smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1751–1761. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SZ, Zeng F, Boulay G, Grimm C, Harteneck C, Beech DJ. Block of TRPC5 channels by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate: a differential, extracellular and voltage-dependent effect. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:405–414. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XC, Sachs F. Block of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeon DS, Kim JS, Ahn DS, Kwon SC, Kang BS, Morgan KG, Lee YH. Role of protein kinase C- or RhoA-induced Ca(2+) sensitization in stretch-induced myogenic tone. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:431–438. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Inadome A, Maeda Y, Satoji Y, Masunaga K, Sugiyama Y, Murakami S. Non-neuronal cholinergic system in human bladder urothelium. Urology. 2006;67:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang M, Birnbaumer L. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx via human Trp3 stably expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells. Evidence for a non-capacitative Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:133–142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]